Category Archives: BAM Reviews

Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker at BAM

Can we ever fathom the underpinning of our relationships with people, the power dynamics, the interplay which inevitably results in the childhood assertion to reign supreme in a parlay of king of the hill? Who dominates in such interplays: the weakest, the most dependent or the one whose presence physically menaces? Is there a power exchange where moment to moment the rapid shifts of control occur depending upon subtle behavioral quirks and personality siftings if the players’ wits are sharpened and prepared for the dynamism? Pinter examines the human power market in his subtly brilliant play The Caretaker now at Brooklyn Academy of Music’s the Harvey Theater through the 16th of June.

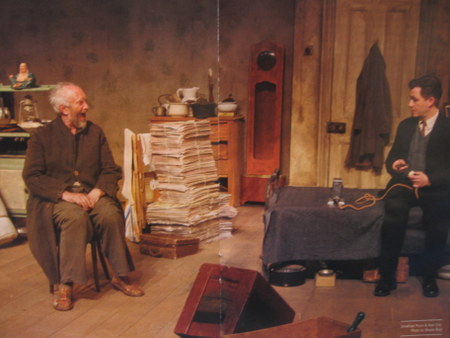

The play starts benignly enough as a roughly hewn street fellow, Davies, played by the superlative Jonathan Pryce is offered shelter by a docile and reserved, mild-mannered, conservatively dressed younger man, Aston, played by the intensely gifted Alan Cox. Everything appears off kilter with the situation that slowly unfolds, down to the contradiction between the civil, kind demeanor of neatly dressed Aston, and the junk heap of a hoarder’s dwelling strewn with garbage dump remnants that Aston expects Davies to stay in for the night, though there is a leak over the bed he offers to Davies and a nearby open window blowing in the rain and wind on Davies’ head. But we gather that down on his luck, unkempt Davies will fit right in and be grateful for even these mean accommodations that have kindly been extended to him. What is amazing is that clean, well groomed Aston stays in the same filthy, rag tag room that Davies stays in. Amidst the heaps of refuse, Aston sleeps in a bed on the other side of the room; its proximity forces him to put up with Davies’ noisy, addled, anxiety ridden dream state which disrupts his own sleep and prompts him to wake up Davies to get him to stop, pissing off Davies. Clearly, we see the conflict points growing and remain perplexed by this weird chaos and at a loss to explain how either man puts up with the situation, though we do realize that perhaps, Davies has no choice and perhaps emotionally Aston has no choice either. Mano e mano, each man has removed the choice of the other in a strange interplay of dependence, want, need, despair and search for some consolation of the soul.

Over the course of the next days, Davies without authority, except as Aston’s appointed ad hoc caretaker, attempts to assert himself over his situation, commenting disgruntledly on the open window and the leak over his head but Aston remains quietly unmoved replying the room needs air. Nothing appears to change in the weather or situation so that Davies who is en route to get his papers and move on to a better life goes no where. Though we know little from the noncommittal Aston who moves with a perfunctory calmness, we sense that Davies may have an individual power of self that Aston may lack, though Aston’s kindness in extending even this shambled place to stay infers a subtle deeper power.

As the play progresses, the roles intensify in the direction which Pinter has initiated with the added complexity of the third member of the dynamic, Mick, played by exceptional Alex Hassell, younger, sinister, brooding brother of Aston. Uncertain as to who he is because of his prowling glare at the onset of the play, we discover his physical authority in the dwelling after Mick has attacked Davies and roughed him up physically in pursuing Davies purpose in the dwelling since Aston isn’t present at that point to tell Mick of his “hiring” Davies as ad hoc caretaker. The attack is both humorous and scary and as Davies is allowed to recover, we see another power dynamic being initiated between the younger brother and Davies. Unlike his relationship with Aston, Davies’ exchange with Mick appears on like footing. However, over the course of the next weeks, there are weird occasions when defying logic, Mick satisfies his joking urges and plays passive aggressive jokes on Davies, using his fears of the “blacks” next door. For example, he unscrews a light bulb so Davies is in the dark when he arrives. Then invisible Mick pops up and down, haunting Davies in the shadowy darkness, all the while completely unnerving the older man. Then a monstrous noise fills the room and we are startled into confusion and alarm for Davies who is cowing and screaming in hysterical panic. A minute later Mick with grinning nonchalance reveals the vacuum cleaner, explaining he wanted to get a bit of tidying up done about the place. Relieved, we laugh, quick to receive the inanity of Mick’s illogical explanation, ready, like Davies, to accept good will over malevolence and torment.

But who vacuums and tidies up in the dark? Indeed, if our wits are about us, we anticipate that Mick is capitalizing upon Davies’ anxieties to make a mockery of the older man while feigning his true motives. Like Davies, we ignore the signs, the incongruities, allowing ourselves to hope for goodness and kindness, for that is the initial situation: kindness was extended to Davies. We, like Davies rattle our minds attempting to gauge the power struggle between these two brothers, to “get on top of the situation.” And like Davies, we are hard pressed to do so becoming lost in a space that is surreal, vacuumed up into the day to day events without understanding, without clarity until our resistance deteriorates and we yield to the whirling merry-go-round of human existence and interaction that the brothers, too, circle in.

The dramatic high points are achieved when Aston reveals his loneliness, his otherness, his “apparent” insanity in a monologue where he reaches out for self-understanding and connection to the world in Davies who appears to be taking it in. We learn that Aston is an extremely sensitive type who, in sharing his perceptions with common folk at a cafe, perceptions that we would liken to those of an anointed adept or finely tuned artistic sensibility, ends up being sent to a mental hospital for observation. The result brings tragedy, a “problem” diagnosis and Electric Shock Treatment signed off by Aston’s mother because he is a minor. As Aston quietly relates the brutality of his resistance and the administration of the treatment we quiver in identification and sympathy, for we understand that something has been taken from Aston and nothing has been returned; he lives with a gaping wound that bleeds and cannot be stemmed, certainly not by interaction with Davies, who is too wounded himself to extend any sufficient help, emotional bandages or antidotes for soul pain and damage.

And from Aston’s revelation the chasm in the dynamic between Aston and Davies widens and Davies, unable to see himself in this man to empathize or reach out, turns to the brother, Mick who ironically appoints him caretaker, though incompetent Davies has poorly fulfilled the role given to him by Aston. We see Davies shift allegiance to Mick, whose claims of authority in the place are circumspect. And we recognize the wave of indulgence as Davies quickly tries to ingratiate himself with a man who may or may not be practical joking with him, convincing himself that he has successfully won over Mick who flatters him when Davies shows he can defend himself physically with a knife if Mick “tries to pull anything on him.”

The dynamic of power, who controls, who attempts to gain the edge shifts and swirls and propels us; we’re spinning with these characters whose centers have not held and whose uncertainty of the upheavals between each other and their own personal confluence estrange them and us in bewilderment. And then in the cataclysm of the ending, for “it,” the turbines of spinning or whatever the “it” may be, must disengage, must stop. In “its” stoppage, we see. We understand how humans need. It is a deep, felt comprehension and we know that in their want, in their attempt to take, they fail miserably, unable to reach an empathy with others because they are alone.

This great understanding is achieved because of the brilliance of Pryce, Cox and Hassell. Their efforts are sublime, elevating humanity to divinity in all its weakness. They are devoted to living in each moment of uncertainty allowing this heavenly development of the active nonaction of Pinter’s unbelievable human rendering. This clearly is the best Pinter I have ever seen, its human truths are heartfelt and cathartic. I thought I was watching Greek tragedy. You cannot miss this production, but probably will as the seats are harder and harder to come by.