Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

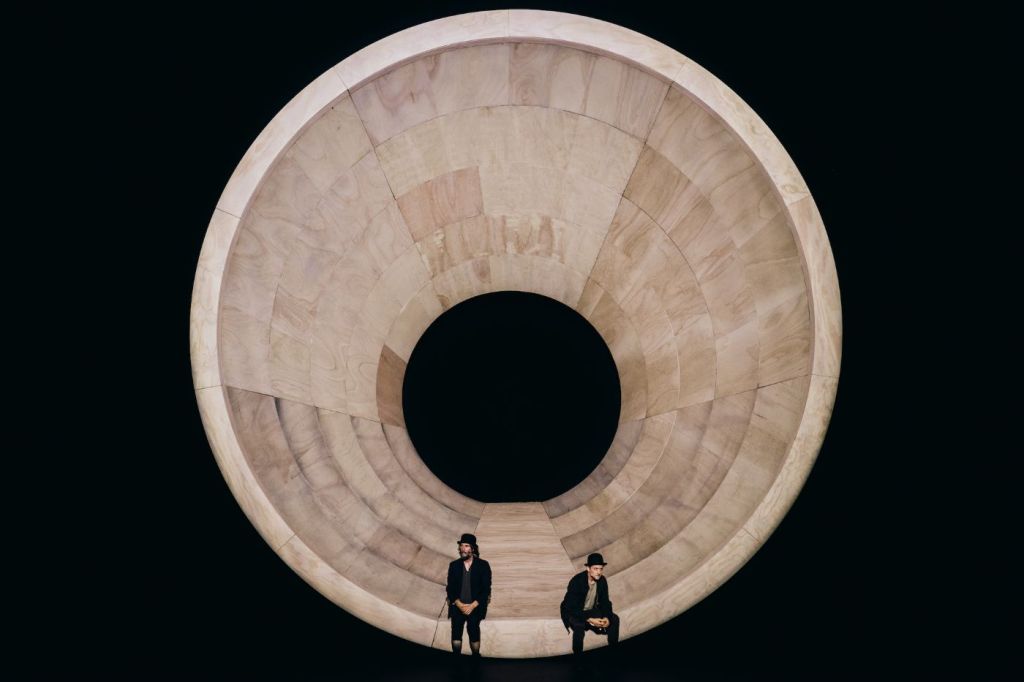

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.

Posted on October 11, 2025, in Broadway, NYC Theater Reviews and tagged Alex Winter, Brandon J. Dirden, Broadway, Jamie Lloyd, Keanu Reeves, Michael Patrick Thornton, review, Samuel Beckett, theatre, Waiting for Godot. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0