‘Bughouse’ John Kelly Becomes the Fascinating Ousider Artist Henry Darger

An unknown until his work was discovered just before his death, the incredible outsider artist and epic novelist Henry Darger (1892-1973) is celebrated at the Vineyard Theatre in the multi-media work Bughouse. Adapted from the writings of Henry Darger by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Beth Henley, the 70-minute play is conceived and directed by Drama Desk and Obie Award winner Martha Clarke.

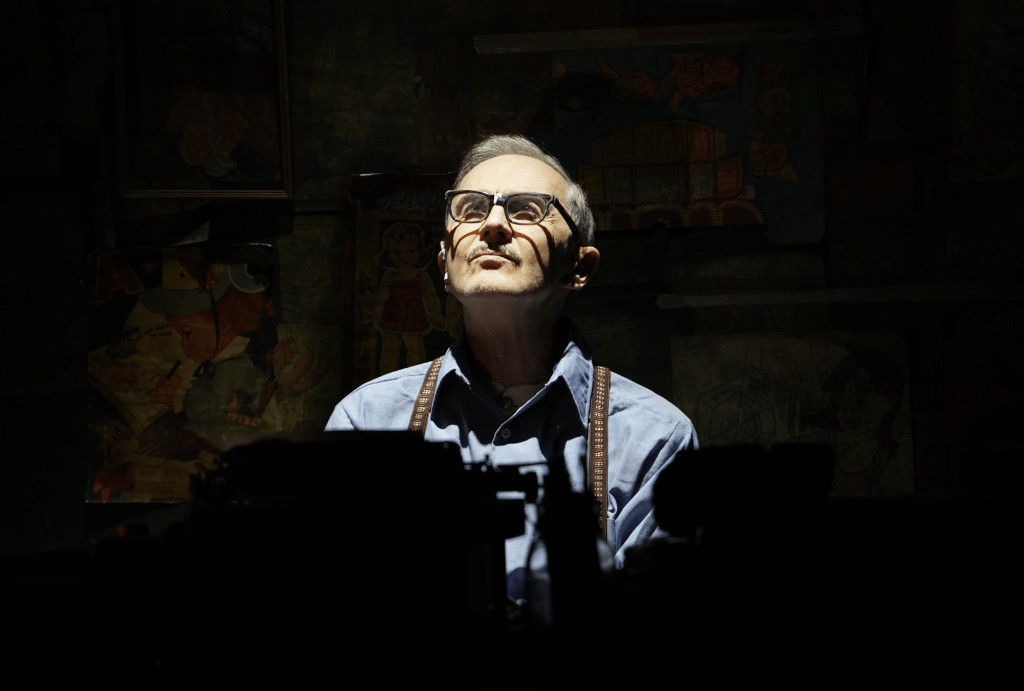

The dance-theater director’s prodigious talents are on full display in Bughouse. Incisively, Clarke shepherds Obie Award-winning performance artist John Kelly to emotionally spin Henry Darger’s creative angst into the fantastical in this beautiful and poignant production. Heartily embraced by its audiences, Bughouse has been extended an additional week until April 3, 2026.

Martha Clarke uses Ruth Lingford’s animation, John Narun’s projection design and Fred Murphy’s cinematography to create the layered realities of Darger’s exterior and interior worlds. She uses animations created from Darger’s illustrations to explore and enhance Darger’s life and work. When projected on windows and mirrors, the “unreal realms” live to the delight of the audience. Kelly’s Darger moves seamlessly through the artist’s interior states of consciousness with enthusiasm and feeling. We can’t help but identify with Darger’s uniquely metaphoric creations. These include archetypal battles between good and evil. When hearing of Darger’s childhood experiences, one concludes the battles express emotional conflicts from his past that he could only reconcile through his artistic creations.

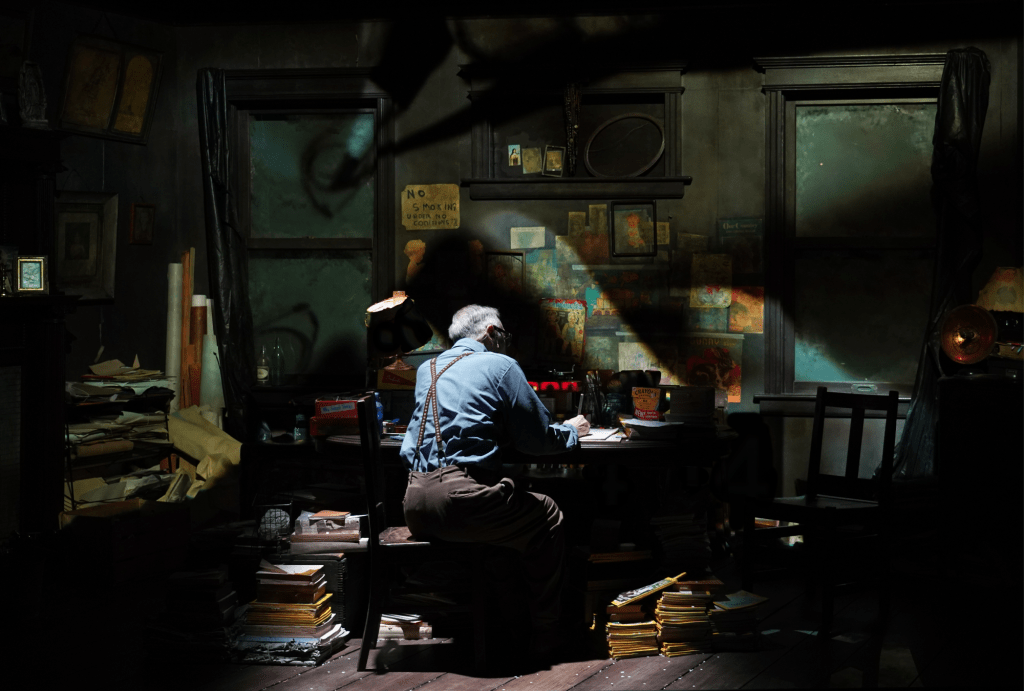

Inspired by photographs of Darger’s apartment, Neil Patel’s production design shows Darger living and creating in a claustrophobic, curio and antique stuffed apartment. In Patel’s recreation, Darger hordes National Geographics and period magazines in piles on the floor. Various items crowd every inch of space in the room. Papers and illustrations cover the table where Darger types up his magnum opus, a few lines of which Kelly’s Darger reads as he types. Beth Henley aptly uses passages from Darger’s epic fantasy in Bughouse (i.e. “The Vivian Girls, fought bravely against the Christian hating, child slave holding Glandelinian demons.”)

The audience becomes Darger’s confidente as we watch his creative process unfold. When he explains his life story, his imagination sparks. Immediately, he moves to type up the continuing adventures of the Vivian Girls, his chief protagonists. “The Vivian Girls…were prettier than fairies and as good as saints and though delicate in form as they looked, they were perfectly strong.”

In their perfection, his characters fight battles in righteousness, overcoming oppression and brutality. Darger explains what makes them heroic when he says, “Beautiful as they were in features however, they were more beautiful in soul doing all that all good children should do, and were so righteous and attended church so frequently every day that their father began to look upon them as saints!”

In between sharing his woeful childhood after his mother died and his father could no long care for him, Darger expresses his hatred of the abuse he experienced as a child. From the nuns in the school he attended, “Mission of Our Lady of Mercy,” and the caretaker at an asylum for feeble-minded children, where he lived until he finally escaped after two failed attempts, Darger was bullied and persecuted for “being different.” Based on various reports and his examination, a doctor misdiagnosed him as feeble-minded when, in fact, the opposite was true. Henry’s father taught him to read at a very young age so he could read the newspaper to him.

We question why these incompetent individuals didn’t recognize or encourage Darger’s talents. But then perhaps snatches of the creative soul of the reclusive, hospital janitor and dishwasher Henry Darger wouldn’t be the essence marvelously portrayed by John Kelly in this fine production. If one believes the adage that pain and suffering produce the artistic drive to express and relieve an artist and writer’s soul’s agonies, then Darger surely is representative.

Thankfully, Darger’s incredible imagination and genius lives on in 350 exquisite watercolors which appear in museums, galleries and collections worldwide. His fantasy novel of 15,000 pages, his 5000 page autobiography and more are available to read.

Caveat: noted is the warning that the content in Darger’s illustrations sometimes depict harm against children as the heroines battle to free enslaved children against evil forces. Also, some of the illustrations depict children without clothes. A few of these images are “included in brief moments in Bughouse.”

Bughouse runs 70 minutes with no intermission at the Vineyard Theatre until April 3, 2026. https://vineyardtheatre.org/shows/bughouse/

‘Marcel on the Train’ a Celebration of Life Using the Silent Power of Mime

Live theater has the power to enthrall while inspiring a deep emotional impact, not only with well-honed dialogue and organic staging, but with movement and well-placed silences. With an emphasis on the latter, Marcel on the Train is mesmerizing and emotionally powerful. The drama is a tribute to celebrated icon of mime, Marcel Marceau. With a fascinating twist it captures a little known fact about Marceau’s life. As a young Frenchman he helped his brother save Jewish children with the French Resistance during the WWII Nazi occupation. This poetic, profound and suspenseful production finely directed by Marshall Pailet is inspired by Marceau’s courage and work in the Resistance. It currently runs at CSC until March 22, 2026.

Written by Marshall Pailet and Ethan Slater, who portrays Marceau, the events begin with an introduction to Marceau’s power to fluidly convey the invisible with simple movements. With these he manifests concrete objects that the audience sees with their imaginations in a silent, collective consciousness.

The opening scene happens in an abandoned train car overgrown with weeds, all invisible. Once Slater’s Marceau mimes sliding the doorway open, he views his surroundings. He sees a flower, picks it, and behold, his hand becomes the flower which opens, then dies. Another cast member enters and joins Marceau in the three sided space that is the train car. His right hand is a fluttering butterfly whose movements are accompanied by a riff of piano music, via Jill BC Du Boff’s sound design. Other performers whose hands are butterflies fill the train car with delicate beauty. Then, they vanish.

The scene transforms with the whistle and chugging sounds of the train. The performers turn into sleeping children and the difficult Berthe (Tedra Millan) screams as she awakens from a nightmare. Marceau attempts to understand her explanation and comfort her with humor in his role as chaperone of the 12-year-old boys (two girls are in disguise) under his charge. The train takes the 20-year-old Marceau and the four “boys” to a Boy Scout Camp in Switzerland to escape Nazi deportation to the concentration camps.

Pailet and Slater disclose the backstory in flashback vignettes where Marceau at various points remembers scenes from the past with his brother or father. These fill in gaps to clarify present events. In one such scene his brother Georges (Aaron Serotsky) discusses the foolproof plan (Jews never become Boy Scouts) to save children. Georges volunteers a reluctant Marceau to take them on a train through Nazi occupied France to the Swiss border. The flashbacks seamlessly return to the present stressful circumstances on the train created effectively with minimal design by Scott Davis and atmospheric lighting by Studio Luna.

As Marceau attempts to comfort the nihilistic, quarrelsome Berthe with humor, she criticizes his bad jokes and throws their dire situation in his face. Her character, though unlikable, provides the forward momentum challenging Marceau to rise above the dangerous circumstances. He persists and succeeds in rocking her off her negativity and fear with the silence of mime.

This becomes the template Marceau uses as he and the children travel toward the Alps, encountering obstacles along the way. Particularly tense scenes concern the unexpected. For example Georges doesn’t meet them at a stop where he was supposed to board the train to accompany them. Other frightening moments occur when they encounter the Nazis, especially as they come closer to their destination and the Swiss border crossing. At these moments of possibly being discovered, the stakes go through the roof. In each case, Marceau proves his mettle by using his art to distract the children and provide the hope and courage to confront extreme danger by believing in a positive outcome. Slater’s Marceau proves his talent using the power of silence and kinetic physicality. His creative imagination entrances the children. Thus, they follow his lead to keep quiet and not fight with each other and expose their true identity.

As a break in this template of Marceau’s softening the hellish situation with his artistry, Pailet and Slater interpose a scene in the future for each of the children. It is Marceau’s affirmation that they will not be captured and die in the camps. For example, Adolphe’s (Max Gordon Moore), future takes place in a POW camp in Vietnam. Marceau told him to remember something from his time on the train, Adolphe uses this remembrance to give himself hope. As a result he lightens the outlook for himself and another soldier despite the hellishness of the POW camp.

Marceau gives each of the children hope by telling them he sees their futures. Of course this inspiration deters them from believing in the present which is peopled by Nazis who intend to send any and all Jewish kinder off to the extermination camps.

The ensemble is superb. The staging and direction surprising and engaging. Slater, whose effervescent performance was perfection in the title role of “SpongeBob SquarePants: The Broadway Musical.” is of necessity the standout in a startling, endearing portrayal he helped write for himself. The scene where he picks up the snow that becomes the white make-up of Bip the Clown is searing and poignant. Slater’s few, profound gestures carry a lifetime of meaning in Marceau’s sixty-year career as a mime and actor in films who most always played himself with ironic silence.

Marcel on the Train runs 100 minutes with no intermission through March 22 at Classic Stage Company. classicstage.org.

‘The Dinosaurs’ at Playwrights Horizons

In The Dinosaurs written by Jacob Perkins and directed by Les Waters, time stands still yet moves in leaps that are hard to figure out. It takes place in a room where women who are alcoholics meet, form community and establish friendships helping each other through the years. With strong performances that require solo monologues, the characters share experiences and perspectives and enumerate their days of continuing sobriety. The Dinosaurs currently runs at Playwrights Horizons until March 8, 2026.

As the characters set up the neutral unadorned room (scenic design by dots), where they meet, wait for participants to show up and reaffirm the rules of their sessions, we understand this is a female inclusive community. April Matthis as Jane is first to arrive to begin setting up chairs, followed by nervous Buddy (Keilly McQuail), who after a humorous exchange with nonjudgmental Jane, decides she can’t stay. She does show up during the meditation and the end only making a connection with Jane in a layering that makes the time structure hard to divine.

Next, Elizabeth Marvel as Joan enters with the coffee and helps Jane set up. She is followed by Kathleen Chalfant’s Jolly as the longest, oldest member of the group, who brings positivity and warmth with the donuts and scones. Newer member Joane (Maria Elena Ramirez), arrives with gossip about a female teacher. Finally, Janet (Mallory Portnoy)–the appointed time keeper–arrives late and is the first one to share on the topic “coming back,” after their group meditation.

The playwright avoids heavy emotional content related to grief, sorrow, regrets, abuse or violence. Indeed, he avoids in the moment conflict in the plot and character development, with the exception of Joan, Jane and Joane who disagree about feeling empathy for a “lonely” female teacher who has sex with a teen who is “of age.” Jolly provides the down-to-earth humorous perspective as the argument persists then ends once Janet arrives. Interestingly, one would think these are average women of various ages who live regular lives, but for their momentous pronouncement later, during their time to share, that they are alcoholics.

The production spends a good deal of time having Joan, Jane and Jolly set up the room making small talk. Chalfant’s portrayal as Jolly mesmerizes with substance, authenticity and humor, which she clearly infuses with backstory and meaning. In comparison with the other women, Jolly’s character is the most delineated because of Chalfant’s superb, specific performance, as is Marvel’s Joan who reveals why she is an alcoholic toward the end of the play. Otherwise, the characters divulge little else about themselves. This forces the audience to imagine who these women are and why they chose alcohol as their drug and not opiates, barbiturates, food or other addictive elements to anesthetize themselves and escape from life’s “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune;” if indeed, that is why they are alcoholics.

Janet’s metaphoric experience about being driven by a chauffeur she hates and who tells her to throw out the body of a man instead of carrying it around, seems to express her situation of carrying baggage which she eventually throws away in her awake dream state. However, we don’t understand to what she refers and she doesn’t connect the dots. Likewise, the others say little hard evidence about their situations. This adds to a general tiresome opaqueness.

All important personal details are absent, perhaps playwright censored to indicate his characters’ self-censorship. No explanation is given by the playwright, which leaves a huge gap in the ethos of the play. Nevertheless, a picture forms of these characters and the process of their recovery from a disease. However, its horrific effects in their personal lives as they share with their community is never identified. Indeed, the recovery process seems deadening as the women avoid discussing even the difficulty of fighting the urge to taste a drop of their favorite alcoholic beverage.

The characters also avoid discussing the severity of their alcoholism. If the blood never boils with emotion, then not feeling alive removes any impulse to drink. Perhaps keeping a steady deadened state is their key to recovery. How fortunate that they have found other individuals who allow this type of emotional void to be shared. Their tell-tale meditation at the beginning of their meeting indicates what substitutes for feeling and the connection with their feelings.

Notable examples of a separation perhaps disassociation from feelings happen with a few of the characters. Joane’s discussion of finding her son pleasuring an older man in their house seems devoid of an emotional reaction on her part in relation to her drinking. The assumption is that her discovery caused the rift between herself and her son that she describes and perhaps this led to her alcoholism. She and her son never discussed or dealt with her seeing her son with the older man. Did this lead to the dire circumstances that happened later in their lives? Ramirez’ Joane recalls it with dispassion though she takes a moment to breathe revealing the confession is difficult. Her admission that she is revealing it for the first time is groundbreaking.

That her son at fifteen was under the apparent influence of an older man reflective of the current pedophilia reports in the Epstein files is passed over without judgment by Joan or any of the other women. Is this what it takes to recover from alcoholism, this passive, non-reactive state of mind while others are there to just listen?

Joan’s time lapse discussion of the days of her recovery to sixteen years emerges with vitality. A matter-of-fact statement of her number of years without a drink that has seen her in this room with various community members of alcoholics hearing her make comments becomes her milestone. And apparently, during that sixteen year period she had to say goodbye to Jolly who dies and whom she misses. Thus, Jolly’s influence on her own recovery is reduced to less than a minute of time, though counting the years of struggle to maintain sobriety must have seemed an eternity. Unfortunately, there is a grand absence of information. Perkins revels in being opaque. More is needed.

Thankfully, the actors do a yeowoman’s job of leaping over the play’s lack of detail by providing as much of their interior substance as possible. Nevertheless, the lifeblood of theatricality and living onstage is hindered by the playwright’s lack of clarity. Nor is the play’s incoherence at times clarified by Waters’ direction.

Perhaps Rainer Maria Rilke’s quote from Book of Hours which Perkins uses to head up his script might have been spoken aloud by one of the characters in a prelude to The Dinosaurs. The lines of poetry present a lens though which to view each of the characters’ journeys, lifting them to a spiritual plane and revealing the irrelevance of time.

I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world. I may not complete this last one but I give myself to it. I circle around God, around the primordial tower. I’ve been circling for thousands of years and I still don’t know: am I a falcon, a storm, or a great song. –Rainer Maria Rilke from Book of Hours

The Dinosaurs runs 1 hour 15 minutes at Playwrights Horizons until March 8, 2026. playwrightshorizons.org.

‘Chinese Republicans’ a Sardonic Look at Chinese Women and the Glass Ceiling

A cross section of how Chinese American women have fared in the corporate world is the engaging subject of Alex Lin’s ironic, humorous and ultimately devastating play Chinese Republicans. Directed by Chay Yew, the well-honed production examines personal sacrifice, identity conflicts, and nuanced discrimination (gender, age, cultural). Currently, Chinese Republicans runs at the Roundabout, Laura Pels Theare, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre until April 5, 2026.

The playwright spins a complex dynamic about Chinese American corporate working women. Yew expertly unfolds the complications among four women of different generations, including one immigrant, working to get her citizenship. During meetings designed to encourage affinity but which actually stir resentments and competitiveness, each of the characters reveals the struggle they face to break the glass ceiling, competing against their less qualified male counterparts. Though the story is unfortunately all too familiar, Lin spikes the interactions with an original, darkly funny approach that resonates with currency.

The production takes off by introducing us to four female suits who work at various upper level positions at Friedman Wallace, as they gather for their “affinity luncheon,” where they meet once a month at a Chinese restaurant. We note ambition, assertiveness and edginess which might as readily be exhibited by any male power-player succeeding in a tough environment. However, these women must obviously work much harder for their success because of internal biases against them culturally as women, and especially as Chinese women. Lin and Yew dance artfully around this gender debility by focusing on cultural elements and details. This strengthens the irony and themes while instructing the audience on elements about the Chinese culture they may not know.

First and most preeminent with experience and knowledge to instruct the younger suits is Phyllis (Jodi Long). She holds little back and uses her irony as a weapon. Ellen, (Jennifer Ikeda), Phyllis’ mentee, has sacrificed having children for her position and plans on becoming partner. Iris (Jully Lee), an immigrant who speaks four dialects, chides the others, especially Ellen on their bad Mandarin and losing touch with their Chinese identity. Lastly, Katie (Anna Zavelson) is the youngest and newest member of the group. Confident and positive about her recent promotion, Katie enthusiastically intones she is excited about their “making a difference.” Then she proclaims, “Come on Asian queens.”

From this luncheon onward, Lin and Yew prove the difficulty for each of the characters to be “Asian queens” in their workplace or their personal lives. Mostly the scenes take place at the restaurant as neutral ground with the exception of the game show farce when Iris ironically shreds Ellen, Phyllis and Katie’s ambitions with irony as part of a fever dream turned nightmare. The side scene after Katie does a turn around and evolves into an advocate for unionizing Friedman Wallace is funny, as she stands in front of the building pumping up a labor rat while the others watch her from the conference room at Friedman Wallace in shock and horror.

How and why Katie reverts to an anti-Republican unionizer from “gun-ho” Asian queen Republican in all its glory involves the corrupt male culture of Friedman Wallace, to discriminatory street violence against Phyllis, to Iris’ immigration hell, to sexual harassment and much more. However, we learn a few twists and turns about each of the characters that add to our admiration of these highly competent women who have endured and suffered nobly, knowing in their bones that not only are the odds stacked against them to ever be at the top, they have strived and sacrificed to what end? A sea of regrets?

The ensemble is uniformly superior. Each portrays their characters with authenticity and a no holds barred approach. As a result the concluding revelations land with poignancy and a powerful kick. The double irony of the evolving meaning of being a Republican is tragic, considering the current face and brand of the MAGA party. Lin neatly slips this information about being Republican into Katie’s development from corporate martinet to human being with a conscience. It’s a reminder to history buffs and salient information for others that political labels are meaningless.

Chinese Republicans fires on all levels of theatricality and spectacle, adhering to Yew’s minimalist, unadorned vision for Lin’s play which focuses on character and themes. Wilson Chin (set design), Ania Yavich (costume design) and other creatives present an attractive backdrop which lends itself to disappearing so the actors are able to live onstage and emotionally, profoundly impact the audience.

https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2025-2026-season/chinese-republicans

Elevator Repair Service’s ‘Ulysses’ by James Joyce, a Review

Elevator Repair Service became renowned when they presented Gatz, a verbatim six hour production of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby at the Public, as part of the Under the Radar Festival in 2006. Since their remarkable Gatz outing, they have followed up with other memorable presentations. It would appear they have outdone themselves with their prodigious effort in their New York City premiere of James Joyce’s opaque, complicated novel Ulysses. The near three-hour production directed by John Collins with co-direction and dramaturgy by Scott Shepherd, currently runs at The Public Theater until March 1, 2026.

At the top of the play Scott Shepherd introduces the play with smiling affability and grace. He directly addresses the audience, reminding them that “not much happens in Ulysses, apart from everything you can possibly imagine,” and that it happens in the span of a day beginning precisely at 8 a.m,, Thursday June 16, 1904 in Dublin, Ireland. Before Shepherd dons the character Buck Mulligan who appears at the beginning of the novel, he discusses that in the “spirit of confusion and controversy” (labels by critics), Joyce’s day in the life of three characters will be read with cuts in the text. Elevator Repair Service elected to remove Joyce’s text to redeem the time. The cuts are indicated by the cast “fast forwarding” over the narrative.

Collins and the creative team cleverly effect this “fast forwarding” with gyrating, shaking movement and action. Ben Williams’ design replicates the sound of a tape spinning forward. To anyone who may be following along with their own copy of the novel, the “fast forward” segments are humorous and telling. However, the cuts pare away some of the details and depths of character Joyce thought vital to include in his parallel of Dublin figures with the most important characters of the Odyssey: home returning hero Odysseus, long-suffering wife, Penelope, and warrior son, Telemachus.

After Shepherd’s introduction, Ulysses moves from a sedentary reading with multiple actors into a fully staged and costumed production as it progresses through the day’s events principally following Stephen Dedalus (Chisopher-Rashee Sevenson), who represents Telemachus, Leopold Bloom (Vin Knight), as Odysseus, and Molly Bloom (Maggie Hoffman) as Penelope.

The events illuminate these characters, and the cast superbly theatricalizes the novel’s humor, whimsy and farce. Some scenes more successfully realize Joyce’s playfulness and wit better than others. For example when Bloom decides to go to another pub after seeing the sloppy, gluttonous patrons of the first bar, the cast revels in portraying the slovenly, grotesque Dubliners. slobbering over their food. Additionally, the scene where Bloom faces his deepest anxieties shows Knight’s Bloom giving birth to “eight male yellow and white children.” Director Collins hysterically stages Bloom’s “labor” with Knight in the birthing position, legs apart, as Shepherd “catches” eight baby dolls he then throws to the attending cast members.

As costumes and props are added to the staging, we understand Leopold Bloom’s persecution as an outsider and a Jew. Also, wee note Stephen Dedalus as the writer/poet outsider who eventually joins Bloom, a father figure, who Bloom takes home for a time until Dedalus leaves to wander the night alone. Chistopher-Rashee Stevenson portrays the young Dedalus, a teacher whose unworthy friends lead him to drink and misdirection. Dedalus grieves his recently deceased mother and toward the end of the play has a nightmare visitation by her frightening, judgmental ghost.

For those familiar with the novel, the cast becomes outsized in rendering the various Dubliners that Knight’s Bloom and Stevenson’s Dedalus encounter. The dramatization is ultimately entertaining. We identify with Bloom as an Everyman, an anti-hero, who tries to get through the day in peace, while dismissing the knowledge that his wife Molly cuckolds him. Though he hasn’t been intimate with her since their baby Rudy died, he is unsettled that she conducts an affair with Blazes Boylan in their marriage bed at home. Somehow, Bloom has discovered that Molly who is a singer will be meeting with Boylan at 4 p.m. that afternoon. On his journey through the day he avoids confronting Boylan as they carry on with their activities around Dublin.

The ironic anti-parallel to the Odyssey, on the one hand, is that Molly Bloom is far from a Penelope who physically remained loyal to Odysseus, where Molly has an affair. On the other hand, late at night as Bloom sleeps with his feet awkwardly next to her face, we understand that Molly still loves Bloom and is emotionally and intellectually loyal. In her stream of consciousness monologue, seductively delivered by Maggie Hoffman, Molly arouses herself with memories of her relationship with Bloom when they were first together. It was then that she transferred a seed-cake from her mouth to his, sensually expressing her love.

Collins’s staging of the scene is humorous and profound. It defines why Molly has been present in Bloom’s consciousness throughout his strange journey traversing the streets of Dublin until he eventually finds his way home to her bed later that evening.

For those unfamiliar with Joyce’s novel, they will find the events and people a muddled hodgepodge that clarifies then becomes opaque, like a light switch turning on and off. Characters swap places with each other as seven actors take on numerous parts in a sometimes confusing array. Only Bloom, Dedalus and Molly stand out, true to Joyce’s vision for Ulysses for they embody Joyce’s themes about life. Thus, Bloom and Dedalus move through the day with flashes of brilliance, revelation, connection, irony and dread. Their reactions interest us. And Molly Bloom in her ending monologue puts a capstone on the vitality and beauty of a women’s perspective, as she experiences the sensuality and power of love for Bloom through reminiscence.

The costume design by Enver Chakartash reflects the time period with a fanciful modernist flourish that gives humor and depth to the personalities of the characters. For example Blazes Boylan (Scott Shepard) who has the affair with Molly wears a straw hat, outrageous wig and light suit that aligns with his jaunty gait. The scenic design by DOTS is minimalist and functional as is Marika Kent’s lighting design and Mathew Deinhart’s projection design. Most outstanding is Ben Williams’ acute, specific sound design which brings the scenes to life and follows the text adding fun and delight.

By the conclusion the audience is spent following the challenge of recognizing Joyce’s Dublin and the three unusual intellectuals and artists who he chooses to explore. Elevator Repair Service has elucidated the novel beyond what one might endeavor to understand reading it on one’s own. Importantly, they’ve made Ulysses an experience to marvel at and question.

Ulysses runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission at the Public Theater through March 1, 2026. https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2526/ulysses

NYBG ‘Orchid Show, Mr. Flower Fantastic’s Concrete Jungle’ Part One

Mr. Flower Fantastic’s Concrete Jungle

A Love Letter to New York in Stunning Orchids until April 26, 2026

The metaphor for New York City as a “concrete jungle” has been used in the past, sometimes with negative connotations that implied ugly buildings, few green spaces, tall skyscrapers stealing light and air, and danger lurking around every corner.

But that conception of the city has long gone with the disappearance of the rotary phone. Alicia Keys’ Empire State of Mind “Concrete Jungle” blew it up forever (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPggPjkoCjE) as did her autobiographical Broadway show Hell’s Kitchen.

Embodying Key’s song’s beauty and excitement, world-renown, in-demand, floral artist, Mr. Flower Fantastic, presents his view of the city in floral pageantry at NYBG. The show is his love letter to New York with captivating cityscapes punctuated with gorgeous, vibrant, many-hued orchids amidst design sculptures and supporting botanical arrangements that highlight familiar objects and places. The ebullient, fun displays present aspects of city life that all city dwellers take for granted and tourists may completely overlook.

In the Palms of the World Gallery, Mr. Flower Fantastic designs moth orchids flowing over and around the iconic townhouse found throughout each of the boroughs of the city.

Who is the show’s creator?

Mr. Flower Fantastic or MFF is one of the most in-demand floral artists in the world, known for transforming flowers into bold, sculptural pieces. Oftentimes, these meld art, fashion, and pop culture. As art comes in a variety of forms, Mr. Flower Fantastic has selected flowers as his medium. This selection carries an irony. Mr. Flower Fantastic is allergic to flowers. In response to this consequence, he embraces his allergies and turns this weakness into his brand strength.

Though his “fantastic” choice of his name and brand is outsized and attention grabbing, yet he is anonymous. You won’t be able to imprint him with facial recognition software because he wears a mask (respirator) and gloves reconciling his allergies with his passion for flowers instilled in him when he was a child. The respirator and gloves embody his style and charisma and allow him to focus on the floral medium as his message with anonymity. The unknown known is his identity.

The creator and NYBG staff selected a variety of showy blooms to cheer us through one of the colder winters in memory. His reiminaging is a lovely meld of “concrete” and green jungle to uplift us and make us smile for its cleverness and whimsy.

Stay tuned for PART II of my CONTINUED COVERAGE of the fantastic NYBG The Orchid Show Mr Flower Fantastic’s Concrete Jungle. In the meantime, check out the programming being offered connected to the show including dates for Orchid Evenings on the NYBG website. https://www.nybg.org/event/the-orchid-show-mr-flower-fantastics-concrete-jungle/

Also, if you would like to check out MFF’s website to look at previous shows and/or items for sale, check this website: https://www.mffstudio.com/

Schedule your plans for a number of visits to the The Orchid Show, Mr. Flower Fantastic’s Concrete Jungle. There is a lot to see that couldn’t be covered in just one post, thanks to the ingenuity of NYBG staff and MFF. The show ends April 26, 2026.

‘The Honey Trap,’ Irish Rep’s Acclaimed Production Returns

Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Carrie Coon and Namir Smallwood are Frightening in Tracy Letts’ ‘Bug’

She’s a cocktail waitress. He’s a Gulf War vet. When they get together they create an unforgettable relationship in Tracy Letts’ sometimes comedic, mostly compelling psychological drama Bug, currently making its Broadway premiere at Manhattan Theater Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre through February 8, 2026. Aptly directed by David Cromer for a maximum thrill ride, Agnes (Carrie Coon) and Peter (Namir Smallwood) gain each other’s trust in a world that increasingly threatens to destroy them.

Stellar performances by Coon (The White Lotus, The Gilded Age) and Smallwood (Pass Over on Broadway) carry the production through a slow build first act into the harrowing intensity and climactic finish of the second.

Letts’ chilling drama unfolds in a motel room on the outskirts of present-day Oklahoma City. Scenic designer Takeshi Kata features a typical mundane bedroom with cream colored walls and complementary cheesy lamps and appointments that spell out Agnes’ challenged socioeconomic position. By the second act, after a time interval during which Agnes and Peter panic and go through stages of emotional terror, the room’s once benign look transforms to a place whose inhabitants are under siege.

At this point Kata’s design shocks. It is then we understand how badly the situation has progressed in the minds of the characters .

At the top of the play we meet Agnes who lives in the motel room hiding out from her violent former husband Jerry Goss (Steve Key) an ex-convict. As Coon’s Agnes and her lesbian biker friend R.C. (Jennifer Engstrom) do drugs, R.C. warns Agnes to protect herself against Jerry whose prison release she questions because he is dangerous.

Ironically, Agnes asks about the background of the stranger using her bathroom. R.C. vouches for Smallwood’s Peter who she brought with her as they make their way to a party that R.C. also invites Agnes to. While R.C. is on the phone with personal business, Peter assures Agnes he is “not an axe murderer,” and expresses an interest in her.

Instead of going to the party with R.C., both Agnes and Peter decide to hang out together and talk, feeling more comfortable getting to know each other than being in a larger crowd. It is during these exchanges and Peter’s staying overnight at Agnes’ invitation that her emotional neediness clarifies. When Jerry shows up, they argue and he hits Agnes. After Jerry leaves, Peter’s attentiveness draws her closer to him. As Agnes and Peter settle in and do drugs, they share secrets and bond. Increasingly Agnes’ perspective shifts. She accepts Peter’s world view and personal reality despite its extremism.

Though Peter says he should go, Agnes uses his hesitation to encourage him to stay, insisting upon it. She makes a symbolic gesture that clever viewers will note conveys her acceptance of Peter because of her emotional desperation more than a belief in his perspective and backstory.

In the next act we see the extent to which Peter has made himself comfortable living with Agnes whose resolve against being with Jerry has strengthened because of her relationship with Peter. Because their concern and care for each other resonates with trust, Peter relaxes into himself. He examines his blood under a microscope and finds “proof” of a conspiracy theory that the government uses military vets and unsuspecting individuals as guinea pigs to experiment on. With convoluted half-truths about government cover-ups related to the war in Iraq, Oklahoma City bombing, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and more, he panics, fearful that aphids bite him and Agnes, feed off their blood and infest their living space.

Convinced that egg sacks have been planted in him by doctors who also monitor and follow him with helicopters because he has gone AWOL, he persuades Agnes to accept his “bug” theory that he grounds in explanations. Together, they plan a way out of the infestation which has taken over their bodies and minds.

To complicate matters Dr. Sweet (Randall Arney) shows up and explains Peter’s medical case with R.C. and Jerry to legitimize taking Peter back with him to “Lake Groom.” Letts offers the intriguing possibility that there may be many truths about this situation. But without independent investigation and research, belief takes over. Whether Peter is part of an experiment and a guinea pig or not, Agnes expresses her love for him comforted by their bond which gives her life meaning. Within the horror of the infestation, they have found their emotional sustenance. Their relationship is their sanctuary from life’s pain.

Cromer’s vision and his shepherding of the fine performances by Coon and Smallwood make this stylized production all too real and terrifying. Thematically current, with various cultural attitudes related to government cover-ups, and conspiracy theories stoked by the questionable motives of those in power, the creative team’s efforts (Heather Gilbert’s lighting design, Josh Schmidt’s sound design) hit the sweet spot of relevance.

Though written decades ago, in Bug Letts intimates how and why certain women embrace what others deem to be their partner’s extremist perspectives. Wounded and seeking love, women like Agnes more easily accept their partner’s ideas, rather than search for facts and proof to dispute them. Governmental cover-ups of the truth fan the flames of extremist belief systems. The consequences can be socially and culturally devastating.

Bug runs 1 hour and 55 minutes with one intermission at the Samuel Friedman Theatre ( 47th St. between 7th and 8th) https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2025-26-season/bug/

The Fine June Squibb Heads up the Stellar Cast of ‘Marjorie Prime’

When Marjorie Prime by Jordan Harrison opened Off Broadway in 2015, starring Lois Smith, it appealed as science fiction. Since then the use of various forms of artificial intelligence to support human behavior have become ubiquitous.

Reinforcing this new reality the playwright and director Anne Kauffman dusted off the prescient family drama and shined it up for its Broadway premiere with few changes to the script. Maintaining the prior production values, director Anne Kauffman works with set designer Lee Jellinek, sound designer Daniel Kluger and Ben Stanton’s lighting design to create the almost surreal and static atmosphere where AI takes over the lives of a family and exists for itself in the last scene.

The production runs at the Helen Hayes Theater with the superb cast of June Squibb, Cynthia Nixon, Danny Burstein and Christopher Lowell through February 15. They are the reason to see the revival.

On one level the excellent performances outshine the themes of Marjorie Prime which deal with death, identity, the grieving process, artificial intelligence and more. The science fiction aspect of the play, so striking before, has diminished.

Yet, Harrison’s conceit that AI holograms might be used to reconcile the death and loss of a loved one still fascinates a decade later. Our culture fights death and aging with its emphasis on ageless appearance, looking 25-years-old at the chronological age of 90-years-old. Some other cultures have a healthier approach, viewing the acceptance of death and aging as a normal part of life cycles. However, with technological advancements, regardless of the culture or country, AI will have its uses in the battle against disease, dying, death and mourning.

The “Primes,” in Marjorie Prime are the spitting image of loved ones at a particular time in their lives. Created by the company Senior Serenity to help the bereaved get through inconsolable grief, Marjorie’s family believes a holographic duplicate of husband Walter will help her adjust to his death. The replica keeps her engaged, sentient and interactive, unlike passively watching TV.

Walter Prime (Christopher Lowell) duplicates the younger, good-looking Walter in his thirties. Happily, he reminds her of the distant past, not the more recent, sick and dying Walter. The hologram’s programming and presence also help stir Marjorie’s memory, complicated with dementia. A work in progress, Walter Prime evolves based on the information that 85-year-old Marjorie (June Squibb), her daughter Tess (Cynthia Nixon), and son-in-law Jon (Danny Burstein), give him about Walter and Marjorie’s life together.

Thus, at the top of the play Walter Prime and Marjorie discuss movies they went to, for example, My Best Friend’s Wedding, which Marjorie has forgotten until Walter tells her the synopsis. The spry 96-year old Squibb, who made her Broadway debut playing one of the strippers in Gypsy (1959), portrays the spicy, funny, confused, chronologically younger woman with a failing memory, an irony that amused me to no end. Squibb is just terrific.

As Marjorie’s identity and memory dim, Walter Prime builds up the identity of Walter with her help. However, Harrison’s play raises questions about this process and never answers them. For example, how much information has Walter Prime been fed prior to his engagement with Marjorie, Jon and Tess? How can Marjorie be expected to keep track of information from before their marriage into their elderly years with her failing memory? Won’t she feed him incorrect details?

Indeed, facts and details shift and Marjorie confuses the truth. An imagined past becomes easier to accept with one’s husband “Prime” fed information by others. This problem never resolves. Neither does Tess’s incomplete acceptance of Walter’s function to stimulate Marjorie, the supposed benefit that Senior Serenity, the company that made him, affirms. The impatient, edgy Tess doubts Walter’s usefulness, but the upbeat Jon thinks that he helps improve Marjorie’s engagement and memory.

When Walter Prime’s presence annoys Tess, Jon accuses her of jealousy. Does Marjorie prefer Walter over Tess, who must nag her mother to eat and “obey” her in the reversal of mother/daughter, parent/child roles? Losing her autonomy Marjorie must rely on Tess and Jon in her living arrangements and personal care needs.

As Jon, Marjorie and Tess converse in Jellick’s minimalist, living room-kitchen combination that lacks futuristic style, Walter Prime sits on a sofa in the living room. He waits in a “listening mode” ready to interact when needed.

For his part Jon is positive about Walter’s impact on Marjorie. As the scene progresses, Tess mentions after an interval that her mother surprisingly recalls a situation long buried in pain. We learn the specifics of this later in the play. Some of the action referred to happens off stage. (i.e. Tess and Jon take Marjorie to the hospital after a fall).

Guided by the “Primes,” who Harrison sequences to move the action forward, time jumps. Marjorie has died and Jon and Tess engage Marjorie Prime to help console Tess and move her through her bleak depression and grief at her mom’s passing. After that we learn through Jon’s conversation with Tess Prime what transpired with Tess. In the various scenes Nixon’s Tess gives a heartbreaking speech about her mother, memory and imagination which sets up the rest of the play. Burstein’s Jon listens and responds with an uncanny authenticity. Both are superb.

Since the “Primes” “live” forever in holographic form until someone decommissions them, they occupy the home in the last scene. Jon is elsewhere, so Walter, Tess and Marjorie converse among themselves having been given life from their human counterparts as an ideal, evolved “being.” Eerie perfection.

Marjorie Prime runs 1 hour 15 minutes with no intermission at the Helen Hayes Theater on 44th Street until the 15 of February. 2st.com.

Kara Young and Nicholas Braun Fine-Tune Their Performances in ‘Gruesome Playground Injuries’

What do people do when they have emotional pain? Sometimes it shows physically in stomach aches. Sometimes to release internal stress people risk physical injury doing wild stunts, like jumping off a school roof on a bike. In Rajiv Joseph’s humorous and profound Gruesome Playground Injuries, currently in revival at the Lucille Lortel Theater until December 28th, we meet Kayleen and Doug. Two-time Tony Award winner Kara Young and Succession star Nicolas Braun portray childhood friends who connect, lose track of each other and reconnect over a thirty year period.

Joseph charts their growth and development from childhood to thirty-somethings against a backdrop of hospital rooms, ERs, medical facilities and the school nurse’s office, where they initially meet when they go to seek relief from their suffering. After the first session when they are 8-year-olds, to the last time we see them at 38-year-olds at an ice rink, we calculate their love and concern for each other, while they share memories of the most surprising and weird times together. One example is when they stare at their melded vomit swishing around in a wastepaper basket when they were 13-year-olds.

How do they maintain their relationship if they don’t see each other for years after high school? Their friends keep them updated so they can meet up and provide support. From their childhood days they’ve intimately bonded by playing “show and tell,” swapping stories about their external wounds, which Joseph implies are the physical manifestations of their soul pain. After Doug graduates from college, when Doug is injured, someone tips off Kayleen who comes to his side to “heal him,” something he believes she does and something she hopes she does, though she doesn’t feel worthy of its sanctity.

Joseph’s two-hander about these unlikely best friends alludes to their deep psychological and emotional isolation that contributes to their self-destructive impulses. Kayleen’s severe stomach pains and vomiting stems from her upbringing. For example in Kayleen’s relationship with her parents we learn her mother abandoned the family and ran off to be with other lovers while her father raised the kids and didn’t celebrate their birthdays. Yet, when her mother dies, the father tells Kayleen she was “a better woman than Kayleen would ever be.” There is no love lost between them.

Doug, whose mom says he is accident prone, uses his various injuries to draw in Kayleen because he feels close to her. She gives him attention and likes touching the wounds on his face, eyes, etc. Further examination reveals that Doug comes from a loving family, the opposite of Kayleen’s. Yet, he may be psychologically troubled because he risks his life needlessly. For example, after college, he stands on the roof of a building during a storm and is struck by lightening, which puts him in a coma. His behavior appears foolish or suicidal. Throughout their relationship Kayleen calls him stupid. The truth lies elsewhere.

Of course, when Kayleen hears he is in a coma (they are 28-year-olds), after the lightening episode, she comes to his rescue and lays hands on him and tells him not to die. He recovers but he never awakens when she prays over him. She doesn’t find out he’s alive until five years later when he visits her in a medical facility. There, she recuperates after she tried to cut out her stomach pain with a knife. She was high on drugs. At that point they are 33-year-olds. Doug tells her to keep in touch, and not let him drift away, which happened before.

Joseph charts their relationship through their emotional dynamic with each other which is difficult to access because of the haphazard structure of the play, listing ages and injuries before various scenes. In this Joseph mirrors the haphazard events of our lives which are difficult to figure out. Throughout the 8 brief, disordered, flashback scenes identified by projections on the backstage wall listing their ages (8, 23,13, 28, 18, 33, 23, 38) and references to Doug’s and Kayleen’s injuries, Joseph explores his characters’ chronological growth while indicating their emotional growth remains nearly the same, as when we first meet them at 8-years-old. In the script, despite their adult ages, Joseph refers to them as “kids.”

Toward the end of the play via flashback (when they are 18-year-olds), we discover their concern and love for for each other and inability to carry through with a complete and lasting union as boyfriend and girlfriend. When Doug tries to push it, Kayleen isn’t emotionally available. Likewise when Kayleen is ready to move into something more (they are 38-year-olds), Doug refuses her touch. By then he has completely wrecked himself physically and can only work his job at the ice rink sitting on the Zamboni.

Young and Braun are terrific. Their nuanced performances create their characters’ relationship dynamic with spot-on authenticity. Acutely directed by Neil Pepe, we gradually put the pieces together as the mystery unfolds about these two. We understand Kayleen insults Doug as a defense mechanism, yet is attracted to his self-destructive nature with which she identifies. We “get” his protection of her because of her abusive father. One guy in school who Doug fights when the kid calls her a “skank,” beats him up. Doug knows he can’t win the fight, but he defends Kayleen’s name and reputation.

The lack of chronology makes the emotional resonance and causation of the characters’ behavior more difficult to glean. One must ride the portrayals of Young and Braun with rapt attention or you will miss many of Joseph’s themes about pain, suffering and the salve for it in companionship, honesty and love.

In additional clues to their character’s isolation, Young and Braun move the minimal props, the hospital beds, the bedding. They rearrange them for each scene. On either side of the stage in a dimly lit space (lighting by Japhy Weideman), Young and Braun quickly fix their hair and don different costumes (Sarah Laux’s costume design), and apply blood and injury-related makeup (Brian Strumwasser’s makeup design). In these transitions, which also reveal passages of time in ten and fifteen year intervals, we understand that they are alone, within themselves, without help from anyone. This further provides clues to the depths of Joseph’s portrait of Kayleen and Doug, which the actors convey with poignance, humor and heartbreak.

Gruesome Playground Injuries runs 1 hour 30 minutes with no intermission through 28 December at the Lucille Lortel Theater; gruesomeplaygroundinjuries.com.