Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga in ‘Macbeth’ a Stark, Thematic Whirlwind to Chill and Confound

Intentional contradictions abound in the production of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth currently enjoying a packed house in its limited run at the Longacre Theatre. Directed by Sam Gold, starring the inimitable Daniel Craig as the titular witch-doomed protagonist and superlative Ruth Negga as his feral, treachery-inspiring wife, the presentation is bold, daring, dramatic, enthralling, surprising, weird, completely irregular and defiant of critical examination.

Yet, the critics have had a field day, a bit reminiscent of Peter O’Toole’s production of Macbeth (1980), that critics ridiculed immodestly. However, the audience found O’Toole and the cast mesmerizing, and packed the Old Vic each night. Gold’s Macbeth is packing the Longacre Theatre despite venom-tongued, snarky criticism.

Macbeth theatrical productions have sprung up as star vehicles for Patrick Stewart, Alan Cummings, James McAvoy and Ethan Hawke to name a few. With each revival, each iteration of Macbeth, there have been intriguing conceptualizations. And this is as it should be, whether in modern dress, in an insane asylum or as this current production, on a stage stripped of showy spectacle, except for some of the Macbeth’s costumes, especially Lady Macbeth’s by Suttirat Larlarb. Gold’s bare stage, the back wall painted black, and Christine Jones’ minimalist set design (save the backdrop against which Macduff and Macbeth fight in the last scene), resemble a rehearsal space. There, the players strut and fret on the Longacre stage, for two hours and twenty minutes. Their discourse is audience directed interaction with resonant, beautifully delivered soliloquies by Macbeth, Lady Macbeth and others, i.e. Ross. Indeed, as Ross, Phillip James Brannon steals the scene where he describes the wanton blood-letting of Macduff’s family by Macbeth.

From the moment witches Maria Dizzia, Phillip James Brannon and Bobbi Mackenzie appear at their kitchen worktable and stovetop making preparations and cooking up their stew (which has a distinctive odor of root vegetables), in this pre-scene before the play, nothing is as what it seems (a key theme). The audience chats. The lights are on. Ushers seat audience members. Many ignore the casually dressed characters whose costumes have less distinction than the audience apparel. It is apparent that Gold is upending our expectations about Macbeth’s movers and shakers, the witches. These are homely, benign-looking creatures of no consequence, “cooking up a storm or two.”

Along with the theme that everything is in reverse (fair is foul, foul is fair), and appearances are not to be trusted, the fog machine (carried by various players) symbolizes misdirection and gaslighting. The fog and mist serves a twofold purpose: to create scenes of foreboding and an atmosphere of doom because reality and truth are indecipherable to the players. Unpredictability is another theme this production brings in from beginning to end. Nothing is assured, no action of the characters is staid; only the lines spoken in various accents are dependably Shakespeare’s (though truncated) in this interpretation which doesn’t quite follow the play’s usual format and dialogue with precision.

Gold shepherds his actors to take liberties, break the fourth wall, at times appear to ad lib, use anachronisms and coy props, like a can of beer for a gallows laugh and employ the acutely strange. For example he has Paul Lazar in a switch off from his role of trusting King Duncan take off his bloody “fat” vest and strip down to his shorts to “become” the porter who receives Macduff (Grantham Coleman) and Lennox Michael Patrick Thornton. All is at the hazard and then it is not. There is comedy in the tragic and a hysterical mania flows throughout. If this is confounding, it is purposeful. The kingdom in chaos and confusion reigns everywhere. Without clarity and leadership Scotland falls prey to a treacherous usurper who transforms the realm to one of darkness, uncertainty, moral weakness, corruption and lies all of whose troubling turbulence will not be easily stemmed. The witches have generated all of these elements.

The witches cook; we ascertain their “agreement.” As they plot, we recognize that the events are being determined, unseen and unknown way before the witches manifest themselves on the heath. By the time they appear to Macbeth and Banquo (Amber Gray), they’ve completed the brew which the witches make Banquo and Macbeth drink, alluring their souls and psyches forever to their fates, ineluctable, irrevocable.

In dramatic irony with emphasis, Gold allows us to see the witches’ power and control. This is something that King James I would have believed, something that Shakespeare wrote for him. I never understood the extent of their power before, thinking they trick Macbeth with the power of suggestion. In Gold’s vision, the witches’ plot has been a while in the making, in another realm and beyond the awareness of all the characters. Thus, we are reminded that before majestic events occur, there are forces at work that may never be understood or gleaned. However, that doesn’t mean that because they are unknown, they don’t greatly influence the events. Gold emphasizes this notion with his pre-play action of the witches.

Additionally, before they state the over arching theme of this production “fair is foul and foul is fair, hover through the fog and filthy air,” at the beginning of the play, out comes Michael Patrick Thornton in antic humor. He discusses the superstition about stating the name of Macbeth onstage, violating the dictum it must not be mentioned and should only be referred to as “The Scottish Play.” After getting audience laughs, Thornton gives an interesting discourse on, James I, King of England and Scotland, his obsession with witches and witch burnings, and Shakespeare’s writing three of his finest tragedies during The Bubonic Plague, where he and others in Europe had to “shelter in.” Macbeth was written during the Plague.

This and more Thornton relates effectively with humor, pacing and irony, addressing the audience as himself, though he later portrays Lennox, a murderer and the messenger of doom for Macbeth. The transition from Thornton in the present to the increasingly serious past events and spell-casting witches is masterfully seamless as we are taken to the hanging and death of a traitor who has admitted and repented his treason against the king, something Macbeth will never do.

The timeless currency of the play abides. Gold (as some critics suggested he should) doesn’t specifically reference the events going on globally (2022) via scenic design or props. He doesn’t need to; the parallels are manifest. The play’s greatness is in its revelation of the best and worst of human nature revealed in the dialogue, events and fine performances by Craig, Negga and the other leads.

Negga’s Lady Macbeth reveals her wicked heart’s desire in her soliloquies. These prepare us for the extent to which she must manipulate her husband by any means necessary, including insulting his manhood and demeaning his fears of failure and pangs of conscience. Not understanding that he is terrorized about the significance of his terrible deeds, she upbraids him for fleeing Duncan’s bedchamber carrying the bloody daggers with him which evidence his guilt. It is as if he begs to be caught and punished for what he’s done; the scene between Negga and Craig is effective and authentic.

By this point the couple has become divided by intent and the consequence of their actions; Macbeth feels the dire results coming, Lady Macbeth does not let it impact her. The shift is clear and Gold never brings them together again with affection. In this first part Lady Macbeth swamps Macbeth’s nobility. She stirs up his acknowledged desire for the throne, despite his rational judgment that no good result will come of killing Duncan, his kinsman and his guest.

As Macbeth, Craig’s, doubt, confusion and fear before killing Duncan and his shock and horror afterward are straightforward and powerful. Likewise, Negga’s Lady Macbeth is steely as she mentally fashions his will and bends it to hers. Pointedly, after both are crowned, Craig’s Macbeth and Negga’s Lady Macbeth accurately reveal the dissolution of their self-respect and love for each other. Craig’s Macbeth becomes obsessed by the negative results his inner guilt has forewarned. After his crowning the witches’ prophecies “fog” his judgment provoking his jealousy that Banquo’s heirs will be on the throne and his will not. Lady Macbeth’s distraction grows after she chides Macbeth at the banquet, the last time they will be purposefully together. She is not apprehending Banquo’s ghost that plagues Macbeth’s mind because of the witches’ prophecy of Banquo’s heirs. At the end of Act I, the witches’ plot is in full force. It submerges any decency left in this once august couple, who now grow emotionally isolated from each other, locked in their own soulful torture chambers.

Gold’s direction of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth at this juncture in their relationship (showing no affection only rancor), indicates that the regicide, whether they want to admit it or not, has been the defining movement of their lives. Everything afterward is a counting down to their deaths. Craig’s performance reveals scene by scene, soliloquy by soliloquy the evanescence of courage with wanton carelessness and cheek (one example is when he gets the beer and drinks it). After he witnesses Banquo’s ghost he admits he is “stepped in blood so far, should I wade no more, returning would be tedious go’er.” Thus, “blood will have blood;” he allows his unrestrained lust for power to expand its corruption and visits the witches for affirmation, which he is duped to believe they give him. But what seems fair, is really foul.

Interestingly, following Shakespeare, Gold and his creative team suggest that the seeds of evil are planted by spiritual forces way before Macbeth’s self-treachery and vengeful violent nature become visible. The corruption and wickedness blossom imperceptibly, then accrue with coverups and lies (symbolized by fog and mist). The more the despotic tyrant doesn’t achieve his goal, the more he furiously lusts to accomplish it with the “help” of the witches who give him an illusory prophecy that he is immortal. This sustains him unstopped by his countrymen, until Macduff (Grantham Coleman) kills him. Indeed, tyrants like Macbeth are never satisfied. When Banquo’s son Fleance (Emeka Guindo) escapes Macbeth’s killing, thwarted, Macbeth shifts his path. Murderous revenge becomes his goal.

Craig manifests Macbeth’s transitions, superbly moving from guilt in refusing to go back to the King’s chamber to smear the chamberlains with Duncan’s blood, to raging at the audacity of Banquo’s ghost coming out from and around the banquet table, returning again and again in a scene that is chillingly effective. And when he attempts to secure his kingdom and learns that Malcolm and Macduff left for England to conspire against him, he has no compunctions about wiping out innocent Macduff’s family in revenge (another powerful scene). He has lost it; logically his blood-lust and terrorism only will inflame his enemies even more and give them license to turn his own subjects against him.

Indeed, blood will have blood, the recurring theme. Negga’s nightmare isolation is acutely staged and rendered as Lady Macbeth envisions blood stains that can never be cleansed from her hand…soul. In this version, Gold and the actors helped me better understand Shakespeare’s behind the scenes look into the human mind, soul and heart of a serial murderer and political tyrant and his unwitting, power-hungry ambitious wife. With brilliance Gold and the actors relay the process of how the wicked couple are snared by conscience then incited by megalomania to never repent. They select the path of emotional self-violation and we get to watch them unravel.

After the bloody combat between Macduff (Grantham Coleman) and Daniel Craig’s Macbeth renders Macduff victorious, Macduff defers to Malcolm (Asia Kate Dillon) as the King of Scotland. In conclusion she takes the power her father rightly bestowed upon her in the play’s beginning.

SPOILER ALERT. Gold truncates Malcolm’s dialogue so she doesn’t invite Macduff and the other thanes to Scone for her crowning. Interestingly, the play continues as an epilogue of irony. The actors put off their roles, fling themselves on the floor, take a well deserved break, and pass around bowls of “gruel” to each other that the witches prepared (offstage). The cast eats their portions silently as the audience watches, (it looks unappetizing). As they eat Bobbi Mackenzie (a witch and Macduff’s slaughtered child) soothingly, lyrically sings Gaeynn Lea’s originally composed song for Macbeth, “Perfect.” The last lines are:

“Tragedy’s viewed through its own lens; but just out of frame sits an old friend, watching our choices play out in the end, returning each other to where we began. Wish I had known it wasn’t meant to be, wasn’t meant to be perfect.”

This may be interpreted in many ways; an ironic apology for what we’ve witnessed as Macbeth’s failure that turned out badly. Indeed, as an “every person” such horrific behaviors can’t “be” perfect, ever. On the other hand it is humanity’s evolutionary process to continue and since we all are mortal, attempting to live forever, as Banquo and Macbeth attempted, the song/play speaks to human foibles. The message emphasizes imperfection, life’s disjointedness and entropy. Every murderous, cataclysmic, bloody, debacle where a despotic nature’s worst impulses for power, regency, a new Russian empire are allowed to be acted out, it is not meant to be…perfect and will not be. Thus, the despot needs to give it up sooner rather than later and save lives in the process. In another interpretation the actors wind down in their community with each other as they seal their commitment to take up their parts and “die another day.”

Shakespeare affirms the sanctity of life and the balance of evil and good in the thoughts of the noble, courageous yet monstrous Macbeth and his Lady as they bring about their own retribution and justice. Their own being effects their demise: Lady Macbeth commits suicide; Macbeth by giving himself over to the process of evil after his regicide. In reality, we can never know the inner thoughts of a Vladimir Putin or Stalin or Hitler. We can only guess at their fears, paranoias and heart’s desires. In Macbeth we have the luxury of understanding the tragedy of their rise and fall.

This is a unique production thanks to Gold, the cast, the superbly effective lighting design by Jane Cox, sound design by Mikaal Sulaiman, special effects by Jeremy Chernick and projection design by Jeanette Ol-suck Yew. Also, the original music by Gaelynn Lea is amazing. For atmospheric effects I particularly enjoyed the crashing revelations (i.e. lighting, sound, etc.) when the ambiguity of the witches’ prophecies clarify (i.e. how Birnam wood comes to Dunsinane). Additionally, kudos to Sam Pinkleton’s movement. Coupled with lighting, sound and special effects the chilling atmosphere of opaqueness and obscurity with the fog machines (which signified the theme of cover ups, lies, obfuscation of “truth”) was strengthened. David S. Leong’s direction of the violence was effected believably in service to the theme of blood will have blood.

This Macbeth will not be duplicated in your lifetime with this community of individuals. It is an incredible experience. For tickets and times go to the website: https://macbethbroadway.com/

‘American Buffalo,’ Explodes in its Third Broadway Revival With Phenomenals Fishburne, Rockwell and Criss

David Mamet’s American Buffalo, first presented on Broadway in 1977 with Robert Duvall as Teach followed with three Broadway revivals. The 1983 revival starred Al Pacino as Teach, the 2008 revival starred John Leguizamo. Eluding the Tony award each time, but garnering multiple Tony and Drama Desk nominations, the 1977 production did win a New York Drama Critic’s Circle Award for Best American Play.

Perhaps Neil Pepe’s direction of this third revival of the American classic, currently at Circle in the Square will bring home a few Tonys. It is a sterling production of Mamet’s revelatory, insightful play about the American Dream gone haywire for a couple of wannabe criminals whose concept of friendship and getting over test each other’s mettle.

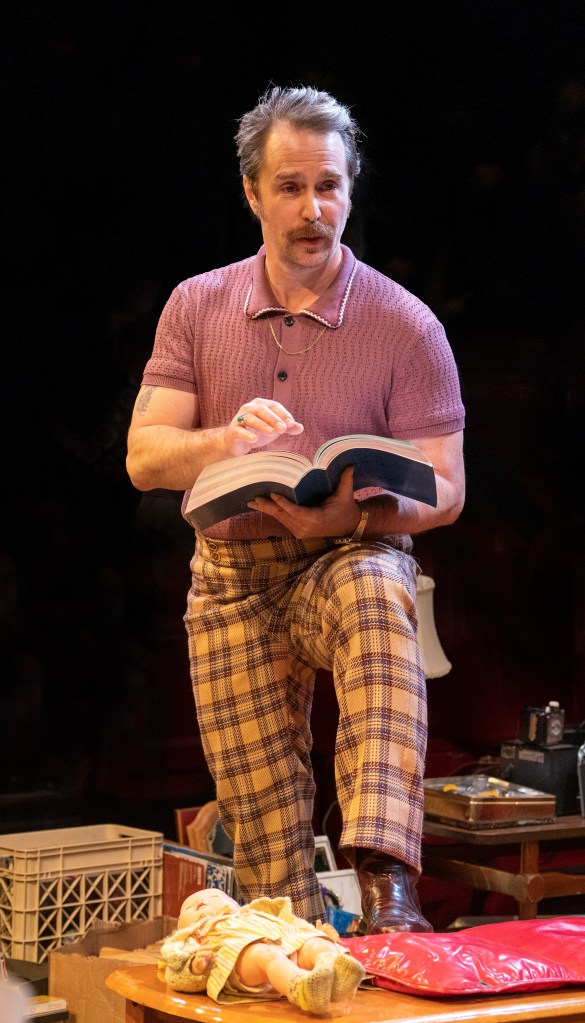

The cast is more than worthy to line up with Mamet’s dynamic, vital characterizations. The actors are seamlessly authentic in the roles of Donny (Laurence Fishburne), Teach (Sam Rockwell) and Bobby (Darren Criss). I didn’t want the play to end, enjoying their amazing energy and finding their portrayals to be humorous, poignant, frightening, intensely human and a whole lot more. Their depth, their interaction, their careful interpretation of each word and action that appeared flawlessly real is so precisely constructed in their performances, it is incredibly invigorating and a justification for live theater-why it is and why it always will be.

Mamet’s early writing is strong and singularly powerful as evidenced in American Buffalo. The play involves a string of events that happen over the course of a day in Don’s Resale Shop which is a hazard of incredible junk for the ages, fantastically arrayed by Scott Pask’s talents as scenic designer. The play opens at the height of drama (we think), when Donny upbraids Bobby about the right protocol to take regarding “doing a thing” as a preliminary action in a future plan they will endeavor. Then the developmental action sparks upward and never takes a breath in the crisp, well-paced Pepe production.

Immediately, we note Fishburne’s paternal and fatherly approach to Darren Criss’ innocent, boyish, “not too swift” acolyte into how to be sharp in business and not let “friendship” get in the way. Donny’s mantra relates throughout American Buffalo. As we watch his interaction with Bobby, we can’t help but see the organic humor in their characters which are contradictory and perhaps disparate from us in intention, discourse, values, initially, but are our brothers in humanity, whether we admit it or not.

At the outset it is impossible not to align ourselves empathetically with these acting icons, each of them award winners with a long history of prodigious talent over decades of experience in film, TV and stage. They are a pleasure to watch as they inhabit these characters, that are a few class steps above Maxim Gorky’s Lower Depths‘ denizens. LIke Gorky’s underclass, these “higher in stature” nevertheless live in their dreams as they deal with the very real and shabby circumstances of their lives. Thus, junk doyen Donny is the wise businessman who, by the play’s end belies all of the instructions he relates to Bobby at the beginning. And Bobby who intently listens to show Donny how much he is willing to learn to remain in his favor, learns little because he has let Donny down at the outset when he is “yessing” him with wide-eyed reception.

As a counterweight to the teacher-pupil, father-son relationship and manipulation between Donny and Bobby, the manic, feverish Teach throws around his knowledge, experience, street smarts and volatile “friendship.” He is their foil, their activator, their stimulator, their inveterate “loser” with a talent for braggadocio and despondency, and clipped epithets about the other denizens in their acquaintance. He is an apparent backstabber and one to watch as someone who sees themselves as dangerous, but botches his self-awareness and presumption to greatness at every turn.

Rockwell knows every inch of Teach and performs him with gusto and relish. He is integral to this team of exceptional actors that Pepe directs to high flashpoints of authenticity and spot on immediacy. This is collaboration at its best. From the layout of their characters’ plans in Act I to the consequences of the plan’s execution in Act II, the still point of behavior is the crux of what Mamet’s Buffalo presents with crushing ruthlessness.

Examples abound throughout, but are particularly manifest in Act II. It is there that Rockwell’s Teach releases the anger within the character to reveal his self-destruction, self-loathing and disappointments. Rockwell’s Teach lashes out, only to be topped by Fishburne’s essentially kind and fatherly Donny, who erupts like a volcano at Teach in a shocking display of force. The drama in the second act is so alive, so expertly staged by J. David Brimmer as Fight Director, if Teach had moved an inch more slowly than he did, he would have been badly injured by the essentially good-natured but seriously, no-joke Donny. The altercation is a work of art, incredibly precise in its build up of the characters’ emotions, then release.

Likewise, Teach’s explosion against Bobby is devastating in another way. Brutal and exacting, Teach exploits Bobby as his victim. Using him as a backboard to release his fury and self-loathing, he redirects Donny to believe Bobby and another individual have double-crossed Donny and Teach in their plot to steal, undercutting Teach’s and Donny’s deal. Bobby’s attempt is feeble as he tries to verbally defend himself against Teach’s relentless onslaught, borne out by Teach’s years of inner frustration which have encompassed failure after failure. Teach won’t hear Bobby. Enraged at himself and his own assumed victimization, as he spews venom on the double-crossing Bobby and his “accomplice” to incite Donny, his violence crashes in a high, then a low.

Once again, the frenemies are tragic counterparts in a social class that is hurting. Teach’s rage is otherworldly. Bobby’s sorrowful reception of it without fighting back is heart-breaking. Criss is just smashing. I wanted to run up with alcohol and bandages to help stem the external wounds, knowing Bobby’s soul harm is irreparable. Through both brutalizations by Fishburne’s Donny and Rockwell’s Teach, the audience was silent in tension and anticipation. And then the mood breaks and here comes humor and apologies and I won’t spoil the rest.

The togetherness and human bonds displayed are as rare as the American Buffalo head rare coin Donny believes he had and lost. The coin lures the three who are governed by dreams of wealth, like iron pyrite. The resultant failure of their plans, emotional devastation and self-harm is never dealt with. Only Donny’s soothing of the situation is a partial rectification. Interestingly, whatever the type of friendship Teach, Donny and Bobby have will be strengthened by the thrill of the gambit, the crooked deal, the need to “get over” to salve lives that exist without purpose, overarching destiny or moment, except to move toward death, with “a little help from their friends.”

This portrait of Americana is particularly heady and current. Though the play is apolitical, it does speak to class, the macho bravado of making plans and screwing up, the lure of illegality as cool, and the consolation provided by the older wiser individual who the younger men are fortunate to befriend, though he is a subtle manipulator and user, as they all are in the game of “getting over.”

In American Buffalo Mamet suggests this game is as American as the American Buffalo, as American as apple pie, as American as the right to bear arms. Indeed, it is in the soil and the soul of our culture and we cannot escape it, though we may not embrace the ethic and ethos of the “art of the steal,” especially when law enforcement comes knocking. Nevertheless, the play suggests a fountain from which to drink and either be poisoned by the perspective, refreshed, nourished, but never bored. For that reason and especially these acting greats, this production should not be missed.

Kudos to Tyler Micoleau’s lighting design, Dede Ayite’s costume design and all the technical creatives whose efforts are integral to Neil Pepe’s vision for this third revival. For tickets and times go to their website: https://americanbuffalonyc.com/

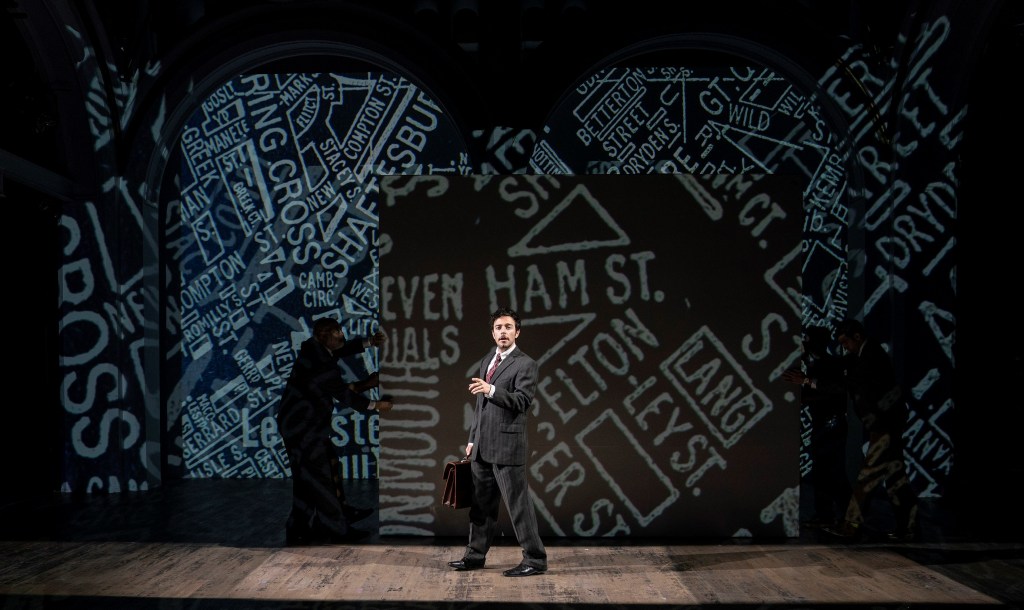

‘The Vagrant Trilogy,’ an Amazing Work by Mona Mansour

The power of The Vagrant Trilogy, Mona Mansour’s incredible work, currently at the Public Theater until 15 of May, lies in the questions it raises. These concern the very real circumstances presented, especially in Act III. Mona Mansour’s connected one-act plays (that took the Public one decade to effect), ask us to empathize with the plight of the Palestinian characters Abir (Caitlin Nasema Cassidy) and Adham (Bassam Abdelfattah). We watch as their world shatters and they have to decide whether to remain in London or go back home to live in a refugee camp in Lebanon.

Before the play begins, the actors introduce the structure and events, explaining that Act I is the set up to explore a decision whose consequences offer two alternate realities. The two different outcomes that occur in Act II and Act III reveal a life of free choice versus a life where one’s every movement is controlled, monitored and limited, as the characters live in squalid conditions, and their upward mobility curtailed unless they escape.

Mansour asks us to consider the extreme consequences of a single decision to change one’s status from culturally displaced immigrant, who gives up everything to live in relative comfort, to that of a refugee who retains cultural identity and family but gives up his comfort and future. The director (Mark Wing-Davey), and the playwright with prodigious effort intend that we empathize with such decisions that the globally displaced are forced to make. These will only increase as wars and extreme events, like climate change created drought and famine destabilize nation states. These will uproot humanity, who will be forced to migrate to places of relative safety, if they can find such places.

Invariably, as we identify with Abir and Adham and walk in their shoes, we ask which sacrifice would we make if we were in their position to choose between Scylla and Charybdis? (Greek mythological monsters Odysseus faced on his journey home) Which monstrous choice would help us retain the most valuable part of ourselves? Or does the act of choosing wipe-out identity, regardless of outcome, as the decision-makers consign themselves to a life of regretful “what ifs,” every time they confront the dire obstacles which are bound to occur?

The refugee camp that Adham refers to throughout the play, is the camp where he and his mother escaped from while his father and brother remained behind. The camp was formed after the first Arab-Israeli conflict in 1948 around the time that Israel was declared an independent state and Palestinians rejected partition and a two-state solution. As a result of the war, displaced Palestinian refugees were shuffled over to Burj El Barajneh, a camp in Lebanon that opened up in 1949. Once there, they were told that they would go home and be resettled, eventually.

One of many refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, the UN has stipulated that they have a right to return. The dictum is ridiculous; there is nothing to return to, nor can they receive documentation to readily return to the area they were forced to flee as casualties of war. Meanwhile, those in the camps wait for a resolution, generations have grown up and moved on. Indeed Adham’s father dies in the camp without ever returning to the homeland he lost. Sadly, the refugees are unable to work or obtain citizenship in the country that hosts them. There’s is a never-ending limbo from which few escape.

Time has passed since the camp was formed and Adham escaped with his mom. It is 1967 in Act I when Adham and Abir meet in their small village in Jordan (former Palestine), after Adham graduates from college. It is right before he goes off to a prestigious speaking event in London where he has been selected out of many talented candidates. Swept up in their attraction for one another, Adham takes Abir home to meet his forceful, prescient, ambitious mother (Nadine Malouf), who disapproves of Abir as a wife.

Not heeding his mother’s warning, he proposes, they elope, and travel to London where Adham garners success at the lecture and is accepted by the faculty (Osh Ashruf, Rudy Roushdi), who he schmoozes with at a party. Fortunately, the exuberant, friendly, faculty wife Diana, (Nadine Malouf’s versatility is smashing in all the roles she portrays), provides the social bridge to make Ahmad comfortable. However, Abir feels uncomfortable, a fish out of water which Adham admits to. But he feels grounded in his subject of literature in academia and he speaks English, which Abir does not.

During the evening of his success at the party, the 1967 Arab Israeli six-day war breaks out. The faculty suggests they stay in London. They will get the couple visas and work out an internship or something available and doable. Abir is distraught about leaving her family and accuses Adham of heartlessly leaving his mother who sacrificed everything for him. The argument intensifies and by the end of it, their emotional fury explodes. The fact is brought out that if they leave, they may never be allowed to return to London as Palestinians, who are now in a state of flux with Israel, the Arab world and the US. They must make their momentous decision and never look back

In Act II Adham’s life unfolds as a professor applying for full tenure. He is still friends with Abir whom he has divorced because of their irreconcialble differences, mainly that Abir blames Adham for staying, a convenient excuse because after the divorce she could return. However, we learn that Abir has it both ways; she accepts little responsibility for her decision to stay and blames Adham for it.

As this section unfolds, we understand Abir’s complaining to another professor friend about him, the same rants; he abandoned his brother and mother and is selfish. She is at the home of Ahmad whom she sees frequently. For his part, Adham’s teaching career is problematic and in limbo without a full professorship. He is neither here nor there culturally; he is like the vagrant he refers to in a Wordsworth poem he has studied and teaches.

Though he has made friends at the university, he finds increasing difficulty with students and faculty as a Palestinian. Act II resolves as he visits the Lake District, the setting of poet Wordsworth’s wanderings which remind him of what he has gained and lost. It is a respite that works in tandem with his discovery that his brother has died in the refugee camp, a casualty of the further escalation of the “eye-for-eye,” “tooth-for-tooth” machinations that occur in the Middle East. Thus, though he is in comfort, he is alone to pursue his career and writings and in a kind of a limbo, without family.

The set design of Act I and II is evocative, with music from the period, projections, and more, thanks to the following creatives: Allen Moyer (scenic design), Dina El-Aziz (costume design), Reza Behjat (lighting design), Tye Hunt Fitzgerald, Sinan Refik Zafar (co-sound design), Greg Emetaz (video design). However, Act III takes place in the refugee camp in the alternate reality that Adham and Abir would have faced, if they returned home.

The Act III set design, sound, lighting are wonderful as they reveal the difficulties and conditions in the camp (power outages, etc.). The two rooms where they live are more tent than shack. There, Adham, Abir, their children Jamila (Nandine Malouf is just incredible as the teen daughter) and Jul (the fine Rudy Roushdi) eat, argue, sleep and manage to survive. The cramped, impoverished, though decorative quarters (rugs and scarves adorn the walls), also hold space for Abir’s brother Ghassan (Ramsey Faragallah) and Adham’s brother Hamzi, (Osh Ashruf in a vibrant enthusiastic portrayal).

It is in Act III where we experience the full impact of their decision to go back “home” which is nowhere, a refugee camp where they wait and wait for a resolution of the Middle East conflict. It never comes. It is heart-rending, and the actors are magnificent in their portrayals which bring Mansour’s themes to their striking and tragic end-stop. What are we doing globally about this? Why? The misery is incalculable. And Ukrainian refugees in Europe and Syrian refugees, etc. and those from South America must be helped. But how? But when? Can the refugee crises ever be stopped?

This incredible production must be seen. The three hours speed by, but it is not for the faint of heart. While I sat riveted, the couple next to me walked out after Act I, while I couldn’t budge from my seat. For tickets and times, go to the website: https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2122/the-vagrant-trilogy/

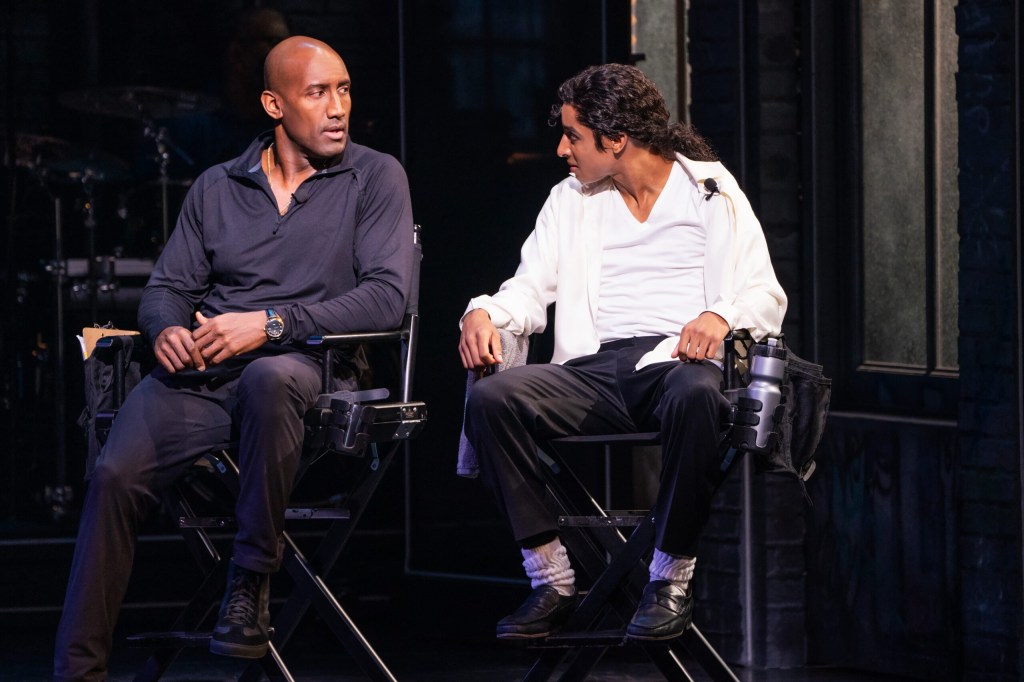

‘A Strange Loop,’ is a Laugh Riot With 11 Tony Nominations

A Strange Loop, awarded the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for drama transferred to Broadway this year after an Off Broadway premiere at Playwrights Horizons. The musical steps into the psyche and being of fat, Black, queer Usher and unapologetically opens the door into his life, dreams and realities as messy and screwed-up and admirable and heroic and amorphous and yearning as they are.

With book, music and lyrics by Michael R. Jackson, directed by Stephen Brackett and choreographed by Raja Feather Kelly, The Strange Loop is currently running at the Lyceum. The production is as particular as a feedback loop stuck on itself, rounding turns with robotic precision, speeding up and slowing down to begin where there is no beginning, and end, well, never. In a very weird and wonderful way, as we view the machinations of how a fat, Black queer deals with being a loathsome/cool fat Black queer, whether one is straight, white, 18-40 BMI female, age 20 and up, or 35- 75-year-old straight, white male 23-40 BMI, or slender Asian or Latina straight or gay male or female, 30-70 somethings, or any identifying LGBTQ individual of any age, shape and size, this satire about identity, sex, race, gender and inner self vs. outer self makes one belly laugh.

Maybe it’s the uber embarrassing put downs Usher sustains with hurt aplomb, reviewing “live” encounters in his imagination (i.e. with the wonderful Jason Veasey on the subway), which plays abusively cruel tricks on him and makes our souls beg for some surcease from the screaming self-torment in his raucous mind, which endears Usher to us. Though there is little to identify with physically, (there were very few fat, Black, queer men in the audience), if one strips away his exterior and listens to him, one identifies with Usher’s sufferings and the “rapid recyclying” thoughts that plague all of us in our incessant and irrevocable “glass is empty” humanity.

In this production, Usher stands before us naked without ego. Unlike us, he admits to humorous self-flagellation. Humorously, he actualizes it so we see his zany mania in all its immediacy, through the songs, gyrations, expansive gestures and verbal somersaults of his inner thoughts portrayed by six talented actors. These include: Thought 1 (L Morgan Lee), Thought 2 (James Jackson, Jr.), Thought 3 (John-Michael LYles), Thought 4 (John-Andrew Morrison), Thought 5 (Jason Veasey), Thought 6 (Antwayn Hopper). All are dressed to “kill him” with unkindness in various color coordinated costumes (designed by Montana Levi Blanco), switched up in the many scene changes. All of these crazies are humorous, exuberantly antic, wild, sassy, picky, aggressive, politically correct, negative, negative, negative.

What they are not is encouraging, uplifting, complimentary. Positive thoughts are not funny. Jackson is about funny insult comedy in A Strange Loop, which also, sometimes is not so funny. This is especially so when the self-humiliating protagonist Usher has the courage and raw desire to “let it all hang out,” including weathering insults about the size of his genitalia to garner LMAO laughs, as he trolls for sex partners on his phone apps (acted out by his thoughts, costumed for the occasion). It is also not funny when he attempts to sexually connect in a graphic, “sensual,” anal, sex scene (with Antwayn Hopper), evocatively staged with blue lighting (designed by Jen Schriever). The end result settles unromantically, poignantly, where he is left in an emotional void and alienating disconnect. We don’t laugh. We silently “take it in.”

The irony we are seduced by is that Usher is a creative who we watch in his creative process, writing a musical about a fat, Black queer-who writes a musical about a fat, Black queer…(continue the loop). Thus, it is an imperative that he embrace his inner wacko with relish, but is his own “straight man” in not cracking a smile as he undergoes his self-delivered smackdowns via his “Thoughts.” That insanity of six shouting manics is the foundation of his art and the subject humor of his misery with which he entertains. Thus, he must not psychoanalyze it away, meditate it away, zen it away or pill pop it away. His extremities of pain take precedence, so his comedic funny man stand-up, song-up can flourish. “Strange” is art, the weirder the better. And as we laugh at this clown, we salve our own inner hell.

In his Broadway debut, the superbly versatile Jaquel Spivey as Usher, whose funny bone is as large as his spirit, draws us in after the few minutes of chaos and boredom he experiences at his job as an usher at The Lion King, chiming the ridiculous miniature glockenspiel-ish bell to alert the audience to their proper protocol. But its Usher’s six soul derivations and tangling loopy thoughts, jangling against each other, ripping into him, bringing up his present condition of being nowhere in his career path as he attempts to write a “Big, Fat, Black, Queer Musical,” that will land him on Broadway. The irony here is absolutely mind-catching because the title of his musical is The Big Loop and here he is on Broadway.

Thus, not only is Jaquel Spivey’s Usher ushering us into a novel kind of weirdo that is all about the interior soul, it is also a joke on us, as Jackson wipes out every BS convention leveled by producers about why certain plays “won’t work” on Broadway or Off.

Well, this one does, with its themes and its representative musical score which is repetitive and driving, characteristic of a loop which Spivey’s Usher coherently describes and explains as he exposes his “bizarre” in real time. In all the commotion of his being, Usher, perhaps Jackson’s alter ego, is laughing the longest and hardest at audience members who are farthest away from the “EWWW fat, Black, gay” loser protagonist.

Spivey’s adorable portrayal is winning and likable because in presenting Usher’s extremely dire misery wryly and sardonically (with his imperfect, voice singing Jackson’s effervescent word crammed songs), we find ourselves tangled interactively in his loops. If we are as honest as Usher, we’ve been there, done that with our own six thought conveyors (maybe more), driving us nuts. And “dollars to donuts” the 20-something guys laughing like roaring lions behind me felt much of Usher’s pain and were thrilled to be able to laugh at him and themselves.

What Jackson gives us with his genius are the fantastic perspectives with which to view this character as he exposes his insults, slights, sword jabs in loopy repetitive three/four crescendoing note melodies that Usher internalized from the cultural, familial influences around him. In various scenes his thought posse, well dressed in appropriate attire shreds and pickles him as he rides the subway, checks out gay apps on his phone to get a boyfriend, visits his mom and dad who insist he write a religious Tyler Perry play, and confronts their censure about his gayness which they find unacceptable.

When the set changes into a Tyler Perry facsimile in a switch up from the neon boxes his thoughts move in and out of through most of the play, the moment happens at just the right time. Spivey’s Usher steps into Perryland, taking on various characters in Perry-type costumes and wigs to please his religious mother who he portrays in the Perry send up, as he sings her affirmation that “AIDS is God’s punishment for being gay,” rousing the audience to “clap along.”

Indeed, the loop has gone around once too many times into debasing self-destruction. Thus, eventually, Thought 4 (John-Andrew Morrison) who plays Usher’s mother in the play within a play, observing Usher’s religious Perry play, breaks the fourth wall and asks him something like, “isn’t this enough? When are you going to let these people go home?” (not the exact quote, but near the meaning)

However, it’s not done; the loop continues. There’s more laughter and amazement to come because Usher is a frenzy of pain and giddiness, with fragmented memories of his father, fearful that Usher might be attracted to him, and his mother telling him she loves him.

Usher can’t process it, but he can reveal it. And somehow that is enough. Perhaps at some point he will “get” that it’s OK, and all of this labyrinth need not be straightened out. Nor should he attempt to emerge from it to achieve “wholeness.” After all, this is his unique contribution and purpose to entertain. If we can laugh about “it” and “him,” then so can he, even though his thoughts may not quite be in the mood to laugh at themselves. But he is his own archetype, an “every person,” so he can bear with that, too.

Kudos to Arnulfo Maldonado’s flexible, seamless multi-faceted scenic design which brings fresh perspective to each, swift scene change, as supple as Usher’s thoughts. Praise must also be given to Drew Levy’s sound design, Cookie Jordan (Hair, Wig, and Makeup Design), Michael R. Jackson (vocal arrangements), Tomoko Akaboshi (music coordinator), Chelsea Pace (intimacy director).

You should see this well-deserved awarded play that has garnered 11 Tony nominations. This is especially so if you need to laugh at yourself. Who doesn’t? For tickets and times go to their website: https://strangeloopmusical.com/

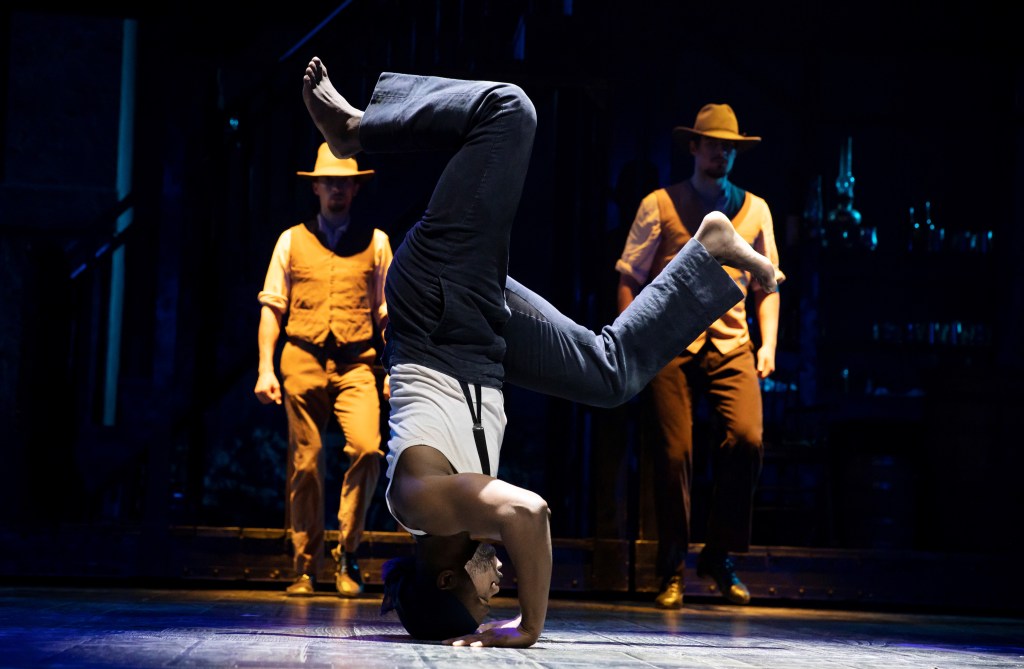

‘Paradise Square,’ a Breathtaking, Exquisite, Mindblowing, American Musical

First there was Lin Manuel Miranda and Alex Lacamoire’s Hamilton which codified our founding fathers through a current lens and brought them into living reality with a new understanding of the birth of our nation. Now, there is the musical Paradise Square which brings to vivid life the embodiment of the American Dream during the Civil War, 1863, after President Lincoln instituted the Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves.

The phenomenal, complex musical is nothing short of a heart-rending emotional shakedown for feeling Americans at this precarious time in our history. Currently, it runs at the Barrymore Theater creating buzz and furor through word of mouth. With Book by Christina Anderson, Craig Lucas and Larry Kirwan (conceived by Kirwan with additional music inspired by the songs of Stephen Foster), music by Jason Howland and lyrics by Nalthan Tysen & Masi Asare, the production’s success is a collaborative effort, and that is a testament to the individuals whose creativity and flexibility brought the spectacular, dramatic elements together coherently with symbolic, thematic power.

With the actors, Alex Sanchez’s Musical Staging, Bill T. Jones genius choreography and the enlightened and anointed direction of Moises Kaufman, the demonstrated will and determination to make this production leap into the firmament cannot be easily dismissed or inconveniently dispatched for whatever reason. (reference Jesse Green of the New York Times)

The setting of this thematically current musical takes place in a slum of cast offs and immigrants who are making the American experiment their own and bringing equanimity to New York City like never before. On a patch of ground in the Five Points that is home to saloon Paradise Square, proprietor Nelly O’Brien (the incredible Joaquina Kalukango who champions the character and all she symbolizes), has created her own version of Eden with her Irish American husband Willie O’Brien (the superb Matt Bogart). There, all are worthy and respected.

Nelly exemplifies the goodness and hope of our American glory and opportunity through hard work, faith and community. Born in the saloon from the oppressed, her father a slave who escaped to the North via the underground railroad, her mixed race marriage is uniquely blessed. It is just like that of her sister-in-law Annie O’Brien Lewis (the superb Chilina Kennedy), married to Reverend Samuel Jacob Lewis (the equally superb Nathaniel Stampley), a Quaker and underground railroad stationmaster. Both couples have prospered, are decent and shed truly Christian light and love on all they meet.

Nelly, the principals and company present life in “Paradise Square,” in the opening song. This is the seminal moment; book writers establish the overarching theme, the hope of America, an Edenic place where all races and creeds get along without division or rancor.

“We are free we love who we want to love with no apology. If you landed in this square then you dared to risk it all, at the bottom of the ladder, there’s nowhere left to fall,” Nelly sings as the patrons echo her and dance. The opening moments clarify what is at stake for Nelly and all who pass through the doors of the saloon. It is a safe haven, where in other areas of the city, the wealthy uptown, for example, these “low class” immigrant whites, and blacks are unwanted and unwelcome. It’s a clear economic divide which grows more stringent as the war’s ferocity intensifies and money becomes the way in to safety and the wall that directs the Irish and other immigrants to the Civil War’s front lines; one more hurdle to overcome after surviving cataclysms and impoverishment in their home countries.

Of course, the symbolic reference is not lost and we anticipate that Eden achieved is not Eden sustained, though Nelly has managed to effect her safe place during the first three years of the war. What keeps her energized is her spirit of hope and her dream which she intends to promote throughout the war until her husband, Captain O’Brien of the 69th regiment of fighting Irish, returns once the Union army has won its righteous cause. Nelly and Willie’s touching song and flashback to their first meeting reveals that they are color blind (“You Have Had My Heart”), and move beyond race and ethnicity to the loving, Edenic ideal which uplifts spirit over flesh and lives by faith rather than sight.

At the top of the production Nelly shows a black and white projection of the modern Five Points and the place where her saloon used to be, as she merges the present with the past and suggests she is relating her story, a story that won’t be found in history books. It is a “story on our own terms,” that exemplifies unity in a community of races and religions bounded by love, concern and financial equality as all struggle to make ends meet, and with each other’s help, get through the tribulations of the Civil War’s impact on their lives.

The exceptional opening song and dance number resolves in a send off of Willie O’Brien and ‘Lucky Mike Quinlan’ (Kevin Dennis) to the battlefield. Both rely on an inner reservoir of faith and Irish pluck, knowing the prayers of the Reverend and all in Paradise Square go before them. The vibrant titular number is uplifting and beautiful as it highlights the American experiment which British royals doomed to failure and Benjamin Franklin ironically stated-our government is “a republic if you can keep it.”

Though the republic has been divided in a Civil War, folks like those who come to Nelly’s saloon believe in nation’s sanctity and are keeping the dream alive, if the South has abandoned it. Indeed, as the book writers suggest, the immigrants and those of passion and heart will hold the dream in their hearts and attempt to manifest its reality because freedom, respect and equanimity is worth dying for. With irony the book’s writers reveal this is something the wealthy do not believe because they don’t have to. Their world rejects the values and ideals of those who people Paradise Square. Without principles worth dying for, the hearts of the Uptowners are filled with greed for power and money. These are the passions that drive the rich, symbolized in the scenes with Party Boss and political strategist Frederic Tiggens (the excellent and talented John Dossett).

Complications develop when Annie’s nephew Owen (the wonderfully talented A.J. Shively), travels from Ireland at the same time that Washington Henry (the wonderfully talented Sidney DuPont), escapes with Angelina Baker (Gabrielle McClinton). Traveling on the underground railroad from Tennessee, Henry arrives in New York City without his love, whom he waits for, braving the dangers of capture. Owen and Henry joined by Annie and the Reverend, a stationmaster on the underground railroad who receives Henry, all sing (“I’m Coming”). The young men, like hundreds before them, seek freedom and prosperity believing in the opportunities afforded by the shining city.

Reverend Samuel alerts Annie that Henry escaped from border state Tennessee which is not covered in the Emancipation Proclamation. Thus, when Henry says he can’t go to Canada, but must wait for Angelina Baker, the Reverend fears for all of them. Nevertheless, guided by faith and Nelly’s extension of grace to Washington Henry, their community stands together and Owen and Henry bunk congenially in a tiny room above Paradise Square saloon.

Additionally, stranger Milton Moore (Jacob Fishel), arrives in their society to beg Nelly for a job. Moore, an excellent piano player with a drinking problem, appears legitimate, so Nelly makes a bargain with him and arranges for Owen, Henry and Moore to create dance and song entertainments to earn their keep. The dancing and singing to a cool multi-ethnic version of “Camptown Races” effected by Henry and Owen who are friendly competitors at this juncture, show the prodigious singing and dancing talents of Shively and Dupont. Guided by Bill T. Jones’ brilliant, energetic and enlightened choreography, the dancing in this production is thematic and symbolic, with unique stylized flourishes that shine a light on the exceptional talents of the principals and the ensemble.

Jones showcases the dances with ethnic cultural elements: for Shively and his group-Irish step dancing; for DuPont-Juba African American dancing that evolved from plantation life. Jones’ wondrous evocations are present throughout. When Henry sings “Angelina Baker” we revert to the plantation where both met. Profoundly rendered through Jones choreography and musical staging (Alex Sanchez), the ensembles’ stylized movements evoke the field slaves soul burdened and bowed, as two plantation overseers tap dance the repetitive torment and the beats of slavery’s oppression and pain. Just incredible!

Uptown Party Boss Frederic Tiggens (the excellent John Dossett) is the villainous snake, whose intent is to divide voters, secure political power and keep wages low by targeting the haven of equanimity, Paradise Square. As a disrupter, he focuses on a “divide and conquer” strategy. Stoking division when the opportunity arises, he is hell bent on destroying Nelly’s prosperous Eden which threatens his political power block. Thus, he foments resentment between the Irish and the blacks when he discovers that the Reverend doesn’t fire a worker to give a job to ‘Lucky Mike,’ a war amputee abandoned by the government he fought for. (“Bright Lookout,” “Tomorrow’s Never Guaranteed.”).

Enraged at the injustice of not being hired by Reverend Samuel who can’t do what he wants or he will be fired himself, ‘Lucky Mike’ becomes the pawn of Tiggens, who exploits his anger instead of helping him. Expressing the plight of many returning vets then and now, Mike’s anger grows into a raging fire with no outlet until it finally explodes in violence. Tiggens’ trouble-making continues with his connections serving financial writs on Nelly and Paradise Square that must be paid off. When she confers with family about raising money, Owen contributes his cultural grace, suggesting a dance festival competition like they had in Ireland. With the festival Nelly will raise enough to pay off the fines. Once again, Nelly and family resilience and hope shine through the darkness of Tiggens’ political machinations to overwhelm them.

Meanwhile, the Reverend is informed by his Quaker friends that Henry has killed his plantation master in Tennessee and is wanted for murder. The Reverend tells Annie who insists she will accompany him and Henry to the next station on the railroad. The song “Gentle Annie” is a humorous revelation of their marriage: Annie’s feisty character tempered by Samuel’s peaceful nature, their shared values and the closeness of their relationship. Kennedy and Stampley give authentic, spot-on performances that solidify one more link in the ineffable chain of love that helps make Paradise Square (the saloon and the production) a place of unity and grace.

A strength of this musical is that the dramatic tension increases and doesn’t let up for a minute. The arc of development in conflicts and intricate, complex themes shows Nelly’s Paradise Square, like Lincoln’s Union strained and stressed. As Tiggens tightens the financial noose on Nelly’s Eden, the announcement of the War Draft threatens the immigrants. Men between the ages of 25-45 must serve, unless they pay $300 dollars to exempt themselves. Lincoln’s conscription is a desperate attempt to revitalize the fight; the Union is on the verge of collapse and the American experiment is in grave jeopardy. Nelly’s dream and Lincoln’s hope of a democratic union run on parallel tracks along with the underground railroad.

For the blacks, the idea that people had inalienable rights and could live together with respect, dignity .and equanimity as a community, the idea that people themselves had the power to sustain such a republic, was keenly felt. Blacks wanted desperately to fight against the Southern oppressors, but were forbidden. (“I’d Be a Soldier”). The Irish, like Owen and the other immigrants, were looking for a better life not war (“Why Should I Die in Springtime?”), but they are ground down by their poverty and question the efficacy of dying for a cause they didn’t create and can’t afford to get out of.

When Owen and the ensemble of Irishmen/immigrants and Henry and the ensemble of blacks sing these numbers, the power of the lyrical music drives home the differences. Both groups embrace the American ideal but are being denied achieving it in reality. As the anger of ‘Lucky Mike’ gains advocacy, it fuels fear in Owen because, for him, the Draft is unjust; he doesn’t have the money. Nelly, for the first time tells ‘Lucky Mike’ to leave her bar as he tries to rally protestors for his (Tiggens propagandized) cause.

As Nelly inspires and encourages her patrons telling them they must not “let the draft break us, that’s what those Uptown bastards want,” an Irishman comes with news that does bow her, Captain Willie O’Brien’s death. But for the Reverend and Annie (“Prayer”), and Nelly’s moral imperative to maintain the saloon’s mission, Nelly would break. As she attempts to gain comfort and inner resolve, the Reverend and Annie confront Henry about murdering his master. In the incredible “Angelina Baker” sung by DuPont with the dancers evoking the Tennessee plantation terrors, we understand his justification for killing.

By the end of Act I, Nelly, Annie, the Reverend, Owen, Henry and the patrons stand on a precipice as the war and malevolent forces threaten to overcome them. Nelly sings, “I keep holding on to hope for a world just out of view, but that hope I have comes at a cost and the cost comes due.” But it is in the song’s refrain that Joaquina Kalukango sings for the ages. Nelly prays with grace and dignity: “Heaven Save Our Home.” Kalukango’s Nelly becomes the intercessor who has made the ultimate sacrifice. All those she loves in Paradise Square are in jeopardy. Her Eden hangs by a spider’s web. As we identify with her prayer, Kalukango’s Nelly stands in the gap for all who are threatened by war and oppression, or unseen forces that would trammel down the sanctity of life. In her portrayal, as she attempts to touch the heart of God, she enthralls our humanity. It is what live theater is all about.

In the transition to Act II, book writers take us to wealthy Uptown New York City. The set changes from the dark saloon, three level platforms, box cages and hard scrabble lines and angles to light, airy, plush furniture in a luxurious drawing room where the wealthy Mr. Tiggens, Amelia Tiggens and Uptown women are being entertained by Milton Moore. Moore presents new versions of songs he culturally appropriated from those he’s heard sung by immigrants and blacks in the Five Points. The scene brings heartbreak at the revelation that “Milton Moore” has been the cover for Stephen Foster (Jacob Fishel).

In a fascinating and ingenious twist in the arc of development, Foster, revitalized by his time in Paradise Square, exploits its greatness, democracy and vibrancy. He brags to Tiggens about his inspired time and unwittingly reveals what Nelly and the others plan. The scene is another dynamo that spills over into chaos when Foster returns to Paradise Square and confronts Nelly, who is arranging to financially save her saloon, Owen and Henry with the dance festival. Foster’s betrayal is a stinging blow. Though he apologizes and attempts to salve the wound by telling Nelly she encouraged his reformation, the danger he reigns down on them is unforgivable. Too late, she ejects him; but the damage has been done. All that is left is to hope that the dance festival brings in enough money to save her saloon and Owen and Henry.

The dance comes off in, another incredible scene with Jones’ amazing choreography front and center as Shively’s Owens and DuPont’s Henry compete, this time not so congenially. There is a winner. You’ll just have to see the show to find out. But the competition doesn’t have the desired effect. Subsequently, New York City undergoes its own class war as the immigrants go uptown in a rage to protest. The NYC Draft Riots, a well documented catastrophic debacle (50 buildings burned, 119 people dead) with destruction, death looting and burning lasts for three days until the US army quells the rioting. As the rioters set fire to Paradise Square, Kalukango’s Nelly confronts them and delivers a message (“Let it Burn”) that defies description in power and spiritual glory.

“Inside this little building is a rare and special lot; we somehow found each other and look what that has wrought; a place you are afraid of, a world you’ll never know; you can take it in a flash; you can burn it down to ash and then out of ash we’ll grow; if you think we’ll run away, you’ve got a lot to learn we are stronger than your fire, and I say let it burn.”

Nelly realizes her Edenic dream continues in greater power without a building to house it. Thus, she gives up the one thing she worked incredibly hard to keep with the knowledge that Paradise Square and all it symbolizes to her is within her soul forever. It is for future generations to manifest and make her Edenic dream a reality.

How the creative team and Kalukango deliver this moment is miraculous. What the show kindles in those receptive to its messages and themes heals, strengthens and affirms. It is the glory of what our country can be in the resilience of the human spirit that uplifts freedom from the boot of financial, moral, ethical oppression and evil in all its forms.

As I watched this production, I couldn’t help but align its “dangerous” democratic themes to events around the world and in our own country. Nelly’s message is the Ukrainians’s message to Vladamir Putin in his unjust war and attempt to destroy Mariupol and other Ukrainian cities with his Stalinist communist terror which cannot succeed. Similarly, I thought of the ultra extremist right wing politicos in the U.S., who would make women heel to their oppression by criminalizing abortion to the point of making it tantamount to homicide, while sanctifying, legitimizing rape. (The rapist becomes a father, bonded to the child and mother.)

The Supreme Court in attempting to overturn settled law, effects a second insurrection more damaging than that of the coup conspiracy by Donald Trump and QAnon Republicans on 6th January. When Kalukango’s Nelly sings her cries for safety and freedom, affirming both by the conclusion, she intercedes for all Americans who still believe with Lincoln in government of, by and for the people. The lrich minority are incapable of hearing such cries from the spirit. They only want to rule like despots.

The values and themes heightened in Paradise Square are truly Christian, American and democratic. The production is a vital happening during a time when political terrorist forces inside our country conspire with foreign adversaries to nullify our constitution and foundations of government based on self-evident truths in our Declaration of Independence; that all are created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights. There is no musical on Broadway today which best represents the American spirit and ideals.

If this does not sound like something you might like, then especially go see it. For tickets and times see their website: https://www.paradisesquaremusical.com/

‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf’ Amazing!

When you have contemplated suicide, the rainbow with all its Biblical and mythological significance is not enough. The pain is cyclical, repetitive and cataclysmic until you end it. However, in ntozake shange’s choreopoem, for the empowering community of black women shining through the clouds of history to speak an anointed truth that has been forged like gold over the centuries, the embodiment of the living rainbow of love is enough.

The revival, currently at the Booth Theatre is directed and choreographed by the anointed Tony award nominated Camille A. Brown (Choir Boys). Shange’s iconic tone poem was initially presented on Broadway in 1976 to great acclaim, transferring its success from the Public Theater. Brown’s re-imagining is a heightened elucidation, different from the 2019 production at the Public Theater which featured mirrors, a disco ball and other shimmering dance party effects.

Brown and her design team have removed elements of reflection in the 2019 production and worked toward an affirming strength in the divisions of light divided through a prism to become seven color bands whose hues are picked up in all the dramatic elements of theatrical spectacle engineered by the creative team. The team manifests the vibrant colors of creation and coordinates them with lighting design effects (jiyoun chang) and eye-popping emergent luminescence in a multitude of shapes projected on large panels on both sides of the stage (myung hee cho-scenic design, aaron rhyne-projection design).

To original music and Brown’s seminal choreography the team ingeniously relates Shange’s poetic story themes. Each monologue and bridge by the company reveal a prodigious conceptualization. As they relate theme to color, the actors’ dance and movement resonate the energy of the color they “wear” (sarafina bush-costume design), enhanced by the coordinated lighting and the projections as the music synthesizes all these elements with astonishing power and emotion.

The large panels on either side of the stage close in the central focus on the majesty of the bands of the rainbow embodied in the following marvelous and sterling actresses who sync exquisitely in choreographed unity. These include Amara Granderson-Lady in Orange, Tendayi Kuumba-Lady in Brown, Kenita R. Miller-Lady in Red, Okwui Okpokwasili & Alexis Sims-Lady in Green, Treshelle Edmond & Alexandria Wailes-Lady in Purple, Stacey Sargeant-Lady in Blue, D. Woods-Lady in Yellow.

As each of the Ladies announce their stories and receive encouragement from their fellow hues, an emotional progression and journey emerges from youth to motherhood to sisterhood, healing and self-love. The emotions from each of the stories move from revelation to relational love and devastation, to acceptance and self-affirmation, to empowerment, with the merging of all the colors to self love which of course is light. (The rainbow is refracted sunlight through moisture prisms after a rain.)

Some of the colors and stories resonate with great joy and the exuberance of youth: the story of graduation night, the beginning of adulthood and sex for the first time by Lady in Yellow (D. Woods). Others take on the hue of the experience described: abortion cycle #1 by the Lady in Blue (Stacey Sargeant), who trails with “& nobody came, cuz nobody knew, once i waz pregnant & shamed of myself.” In the bridges to the monologues the rainbow ladies add their encouragement and dance with superb breath control and conditioning.

I particularly enjoyed Tendayi Kuumba as the Lady in Brown who humorously expresses her inspired love for “Toussaint,” whose books she discovers by sneaking into the adult section of the library. As a first foray into the world of a love mentoring, and influence, she lifts up the Haitian freedom fighter and he becomes her lover (she is a precocious 8-years old), and confidante late at night as they conspire “to remove the white girls from my hopscotch games.” The resolution occurs when she meets a “real-live-boy” named Toussaint who is interested in her. When she considers the great distance she must travel to Haiti, she decides he’ll do fine.

In the brilliant “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff” the Lady in Green (Alexis Sims when I saw it), identifies how the soul can be stolen. The outrage and anger belies the humor underneath as the audience realizes the Lady in Green’s outcry hits home. How many have subdued their inner voice and being for the sake of pleasing another and then didn’t process the identity theft until too late? When emotion and feeling end up residing in the power and confidence of another because of bestowment is this not a form of theft? As one of the more powerful of Shonge’s poems anger is appropriate because the theft is subtle and secret and must be watched or one loses everything.

Perhaps the most telling and dramatic is The Lady in Red’s monologue “a nite with beau willie brown.” Presented by the pregnant Kenita R. Miller, we understand the raw horror of a man who has gone over the edge with PTSD and who brings down everyone else around him. With three children willie brown is emotional, irrational and sly. He desires control and power over the Lady in Red and has beat and manipulated her. However, she has had enough. Miller’s performance builds and intensifies as she compels us to feel the real plight of trying to save the lives of children from their abusive biological father who doesn’t take responsibility for raising him; they aren’t married. Delivered with incredible empathy, love and force, Miller’s performance is breathtaking. Clearly, deeply she reaches the soul level, indicating what it is like to confront one who has learned to kill and can’t turn it off. Just dynamite.

Camille A. Brown has infused an emotional reality in the presence of these ladies of color that is felt and is experienced. Not only has she discovered the way of story telling through the actors’ rich performances, she has threaded their beauty through movement and dance, steady drum beats and lyrical notes of powerful, velvet femininity.

This is emphasized throughout, but perhaps most in the “laying on of hands” in which all of the hues anoint each other and the Lady in Red expresses in the beginning of the segment that there was something missing. But by the end in the company of the rainbow women, she states, “i found god in myself & i loved her/i loved her fiercely.” Only then after the expurgation of all that is ill in the culture to receive and distinguish all that is loving and graceful, the Lady in Brown concludes, “this is for colored girls who have considered suicide/but are movin’ to the ends of their own rainbows.”

Cookie Jordan’s hair & wig design speaks out to individuality, empowerment and self-confidence. This especially resonates in a world where women’s rights and “colored” women’s rights have been dismissed by white men who intend to rule like demented, genocidal lords over us if we let them.

The original music, orchestration and arrangements by Martha Redbone and Aaron Whitby flow seamlessly in and out of the gorgeous mosaic of Brown’s dance and movement choreographed to perfection against Shange’s poems, backdropped by sustained flashes of scintillating color projections. Drum arrangements by Jaylen Petinaud provide the beating heart of Shange’s work, pulsating energy and life. The music and drums electrify the actors who in turn electrify the audience in felt, authentic moments. Tia Allen as music coordinator and Deah Love Harriot’s music direction provide further grist to this intense team work that brings such memorable force to Shange’s masterwork.

This must be seen by every woman as it is an incredible, uplifting production that explores the secrets in every woman’s heart, unexpressed, felt, experienced. The production’s currency aligns with the recent Supreme Court draft to turn down Roe, an abomination of desolation, un-Christian, indecent, genocidal. Juxtaposed against wickedness, Camille A. Brown’s production is an affirmation of hope and the glory of womens’ empowerment to throw off the darkness. Indeed, as Shange shows us the way; the rainbow in the full representation of a unity of all colors in self-love is the light.

For tickets and times, go to their website: https://forcoloredgirlsbway.com/

‘The Minutes,’ Too Close For Comfort, a WOW!

The beauty of Tracy Letts’ The Minutes, directed by Anna D. Shapiro is that there is no hearty mention of political parties in Steppenwolf’s “very American” production whose patriotic music blares as the audience takes their seats at Studio 54. The music (Andre Pluess), and the City Council’s meeting room set design (David Zinn), remind us that it is in the small towns and cities of our democratic government that the American Dream comes to fruition, as it moves toward the hope that in our country, all men and women are created equal and are guaranteed their inalienable rights stated in the Declaration of Independence as under-girded by the constitution.

During The Minutes, the veil is lifted so we may watch democracy in action, vaguely referenced by Big Cherry’s Mayor Superba (Tracey Letts). What occurs on this momentous rainy night, when the city council gathers in a quorum to conduct its business, is a bludgeoning reminder of our blind hypocrisy regarding our pretensions to democratic self- government. When uncontrollable atavistic compulsions in our natures arise and dominate the best of us, is it even possible to govern with equanimity, Lett’s and the creative team ask?

This question appears to be at the heart of Letts’ rich and profound exploration of an Everyman/Everywoman city council, one of whose members we discover toward the last twenty minutes of the play is a whistleblower. What happens to him reveals the power of what America can and should mean vs. what America is revealed to be, in its local governments which often usurp our nation’s lofty principles and subvert them into governance by raw, destructive emotions born out of traditions of fear and hatred.

The point is made that the elected officials that govern Big Cherry, the central focus of this fascinating production, are neither Republican or Democratic. Nor at first do we anticipate that this council is anything but a representative democratic institution that functions as a proper governmental council should, with an emphasis on doing what is “the best” for the constituents who elected these men and women. In addition to Mayor Superba the board members include a bi-racial, gender appropriate, non-ageist group who look to be inclusive and bring inclusive issues to the fore as presented during the meeting.

The officials include Ms. Innes (Blair Brown), Mr. Breeding (Cliff Chamberlain), Mr. Blake (K. Todd Freeman), Mr. Hanratty (Danny McCarthy), Ms. Johnson (Jessie Mueller), Ms. Matz (Sally Murphy), Mr. (Austin Pendleton), Mr. Peel (Noah Reid) and Mr. Assalone (Jeff Still). Note Letts’ clues of character with the particular, irony weighted selection of names. The names push the envelope of belief to convey the play’s sardonic tone at the beginning.

Vitally, the tone and humor increasingly morph toward revelation of the mystery of the previous week’s minutes that end in the shocking banality of evil at the play’s conclusion. As the production devolves into atavistic horror, we understand the city council’s cultural appropriation of the Sioux’s tribal dance. Incredibly open to interpretation, it symbolizes how they approach their concept of city council government. They attempt to empower themselves as warriors of their mission which they take to a radical extreme, defying the national, constitutional mandate while wickedly, hypocritically posing to uplift it.

The play drives to the heart of the dangerous atavism in this nation on both political divides without stating “Democrats” or “Republicans;” the party is not the point. Human nature is the point. Whether its book bannings, “don’t say gay,” Southern botch job of COVID as politicians and QAnon representatives scream “my body my choice,” then turn around and reverse “my body my choice” women’s rights with abortion bans, or the smear job screamed out by rabid #metoo pretense, pushing the ouster of former Governor Cuomo, equanimity and rationalism aren’t to be found.

Letts’ drives this home…revealing how the mundane often cloaks the dark, emotional abyss underneath. If only Satan sported horns, chains of diabolism and wore a name tag hailing his identity. Too often the sweetest people are the most malevolent, especially if they are working for your best interests in government. Ah, “something wicked this way comes and it’s the human heart.” BEWARE!

Without going into the specific plot points because there is no spoiler alert, at the top of the play, Letts introduces us to the EVERYMEN AND EVERYWOMEN city council members who are “average” individuals of a cross range of the “middle class.” At the outset, as they arrive, they move into their friendship groups, to elicit support from each other for their proposals that they intend to present at this evening’s meeting.

Throughout the play Mr. Peel questions what happened at the previous week’s meeting which he missed because his mother passed away. Mayor Superba and Mr. Hanratty casually dismiss Mr. Peel’s questions at the outset. However, Mr. Blake suggests that he will be rebuffed roundly and warns him that Mr. Assalone will lead the others against him so he won’t get anywhere with finding out what occurred.

Lett’s cleverly sets up the conflict focusing on what happened, why no one wants to discuss the previous meeting and what happened to Mr. Carp (Ian Barford in a profound dramatic performance) who is absent and apparently is no longer on the council. With a weird dismissal of Mr. Peel’s questions which under the law must be answered, we and Mr. Peel are set to wondering whether this is a cover-up and who and why the previous meeting cannot be easily discussed. We also wonder, along with Mr. Peel, what happened to Mr. Carp and why the duly elected official is no longer on the council. Was it Mr. Carp’s choice, Mayor Superba’s choice or the council’s choice that he left?

This relatively new council member Mr. Peel, who we discover a bit later had become friendly with Mr. Carp and supported his cause is no wiser about the circumstances as the meeting comes to order with the typical prayer and pledge of allegiance as all governmental meetings follow with sleepy, traditional protocol. Thus, we forget Mr. Peel’s questions and concern and with the demonstrated banality of what we’re familiar with, settle into regularity until Mr. Oldfield presents his case for an important consideration, an empty parking space.

Oldfield portrayed by the esteemed and wonderfully LOL, on-point Austin Pendleton conveys much of the humor in Lett’s The Minutes. In whatever he does Pendleton is a standout of authenticity and moment. Once Mr. Oldfield and his subtle request about the parking space is dismissed, the business at hand is presented.

Mr. Hanratty and Mr. Blake have their pet projects which eventually are objected to and voted down. Interestingly, the figure on the fountain that Hanratty wants to renovate gives rise to how the figure represents the foundation of the city. The members who are in the know provide the dramatic re-enactment of the mythic Battle of Mackie Creek that the figure’s heroism is dedicated to in the fountain. Only Mr. Peel is not familiar with the history of Big Cherry because it is his wife’s birthplace, not his. Thus, he does not take part and watches as Big Cherry’s history rises up from its past in a re-enactment.

All take part, even Mr. Oldfield, who provides the horse hoofs’ sounds. Their “theatrics” are humorous and the actors, as their council counterparts really ham it up appropriately to audience applause. Thus, we are reminded of such mythic re-enactments that traditionally dot the nation as harmless fun. However, the Civil War re-enactments are perhaps more than that for those who take part yearly (before COVID). Letts and the creative team call into question their significance and symbolism. To what end do those go to the trouble to show up and fight with accurate replicas of guns, cannons, outfits, and some even living on the fields for a week or more to “remember.” Curious.

Letts opens one’s eyes to conceptual meaning made physical. With regard to the Civil War, the devastation and destruction…one questions why re-enact it yearly? How can bloodshed (the greatest number of casualties in a war before COVID) and violence be fun? (Interestingly, COVID will have killed twice as many in the same time period. Thus far, there are a recorded number of US deaths at over one million twenty thousand on Worldometer in a two-year period.) However, the re-enactment is relished by the council members because it manifests glory in their history. It binds them in community and makes their lives as council members meaningful. Of course, the further symbolism and importance of this act blossoms by the conclusion.