Blog Archives

‘Father Mother Sister Brother’ With Adam Driver, Cate Blanchett, Tom Waits @NYFF

Father Mother Sister Brother

Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Lion award winner at the Venice Film Festival is a quiet, seemingly unadventurous film that nevertheless packs a punch. Instead of car chases and bombs exploding, Jarmusch employs subtext, nuance and quietude to convey family alienation.. His dangerous IUDs include slight gestures, a raised eyebrow here, a smile there and stilted, abrupt silences throughout.

Jarmusch quipped in the Q and A during the 63rd NYFF screening about such captured details of human behavior. To focus on nuances and what they reveal becomes much more difficult to film and edit rather than “12 zombies coming out of the ground.” Certainly the laconic characters portrayed by superb award winning actors (Charlotte Rampling, Adam Driver, Cate Blanchette, Tom Waits, Vicky Krieps, the beautiful Indya Moore and Luka Sabbat), hold one’s attention as masters of understatement. Indeed, Jarmusch forces us to carefully observe them because of what they don’t say, as they ride the pauses between what they do express.

Jarmusch’s triptych of meet-ups among family members rings with authenticity. Principally because Jarmusch wrote the parts for the actors he selected, the dialogue and situations unfold seamlessly. Of course the stilted silences fill in the gaps between parents and children when both are fronting about what is true and real. To what extent do we cut off 80% of what we would like to say to “keep the peace,” “mask our true emotions” or “get over?”

The film divides familial separation into three scenarios in three locales. In the last sequence, the separation has no hope of reconciliation. In the first scenario a slick, quirky father (Tom Waits) hosts his children (Adam Driver, Mayim Bialik). In their ride to his house in a wooded area by a lake, the brother and sister discuss how their father has difficulty making ends meet and may have dementia. Ironically, when they share that he hits them up for money, they haltingly discuss that they give it to him. Sister Mayim Bialik humorously comments that the frequency and amount may have contributed to her brother’s divorce. Then she ruefully realizes her insulting remark and apologizes. Their conversation reveals, they too, display an awkwardness with each other.

Of course this ramps up when they sit down with their father who offers them only water to drink, instead of something more. However, his wife, their mother passed, so assumptions abound. For example, they assume his shabby, messy living room signifies he struggles with her loss. And perhaps his lack of funds and sloppiness reveal a purposelessness in his own life without her. However, when Jarmusch has the children leave, we note the reality behind the assumptions. Waits’ Dad transforms into someone else. Not only have the grown children underestimated their father, they’ve completely misread his personality, character and intentions.

The scene is heavy with humor. Indeed, it reminds us that the Italian proverb “You have to eat 100 pounds of salt with someone to understand them,” isn’t an exaggeration. And this thematic thrust Jarmusch has fun with in the next scenario as well.

The second interlude takes place in Ireland, where a wealthy novelist mother (Charlotte Rampling) hosts a formal tea for her grown daughters who live in Dublin (Vicky Krieps and Cate Blanchett). The lush setting and table filled with all the proper treats for an afternoon tea impress. However, the sophistication of the setting adds to the cold atmosphere among the daughters and mother who play act at niceties. The daughters appear at opposite ends of their lives. Kreps with pink hair contrasts with Blanchett outfitted with glasses, short cropped hair and regressed to dour blandness. Rampling’s remote, regal mom presides over all austerely.

Before the daughters arrive, the mother reveals her attitude about the tea. Krieps alludes to a relationship with another woman. However, none of the interesting frequencies in their real lives come to the table. Instead, they drink tea politely accomplishing a duty to their blood. Truly, folks may be related by DNA, but their likenesses, interests, values and personalities may have little alignment with their blood kinship. We do choose our friends and are stuck with family relations.

Interestingly, the third segment returns to the theme of children not understanding their parents, who grow up in a different time warp. In Paris, two lovely-looking fraternal twins (Indya Moore and Luka Sabbat) make a return visit to their late parents’ spacious apartment. Their parents, who died in a plane crash, have separated from them for the rest of their mortal lives. As they walk through the empty apartment then go to their parent’s storage unit, they confront the impact of their parent’s deaths. Additionally, they marvel at their parents’ things. These had little significance to them but had meaning to their parents who kept them and paid for the storage.

Of the three scenarios, in the last one Jarmusch reveals the love between the siblings. Additionally, he reveals a potential closeness to their parents. As they go through a few old photos, they show their admiration and they mourn. However, what remains but memories and the stuff in the storage unit whose meaning is lost to them? The heartfelt poignance of the last scenario contrasts with the other family scenarios and lightly holds a greater message that Jarmusch doesn’t shove down our throats.

Jarmusch’ Father Mother Sister Brother reveals profound concepts about family, human complication and mystery of every human being, who may not even be knowable to themselves.

Father Mother Sister Brother releases in US theaters at a perfect time for family gatherings, December 24, 2025 via MUBI, where it will stream at a later date. For the write up and information at the 63rd NYFF, go to this link. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/father-mother-sister-brother/

‘Burn This,’ Sparking Flames Between a Smoldering Adam Driver and Cool Keri Russell

Keri Russell, Adam Driver in ‘Burn This,’ by Lanford Wilson, directed by Michael Mayer (Danielle Levitt)

Part of the fun of watching Lanford Wilson’s characters in Burn This includes noting their particularity, their measured “normalcy,” their zany, hyped-up incredulity. Concisely directed by Michael Mayer for authenticity and humorous grist, Burn This in its New York City revival drifts, flares up, subsides, then rages. The characters circle each other, collide, implode, retreat with tenuous watchfulness, then boil over, coursing the play to an uplifting conclusion.

What makes this an intricate production is the dynamic of the relationships centered around Anna (Keri Russell) the smooth, sylph-like dancer who evidences a shine for artistic endeavor and the artfulness of restrained love. However, Anna is undone by the haphazard. It comes in the prodigious shape of earthy, sensual Pale (Adam Driver) who like a force-of-nature inflames subterranean passions and blasts her out of her staid romance with Burton (David Furr) and easy routine with gay roommate Larry (Brandon Uranowitz).

After Anna’s one-time sizzling encounter with Pale, unbeknownst to Anna, her elaborately constructed inner psychic protections are shaken to their foundation. Her external “cool” and artistic resolve are broken wide open with the affirmation of life’s most chaotic of emotions which irrevocably will spin her into a relationship with the amazing and sensitive Pale.

At the opening of the play, Larry and Burton reveal their need for the friendship and the attention of the grace-filled and gorgeous dancer, whose nurturing kindnesses and moderate emotional tenor roll up and around marketing whiz Larry, and successful, screenwriter Burton. Anna receives comfort from both men in this expositional scene as they console each other about the loss of Larry’s and Anna’s other roommate, Robbie to an unfortunate accident.

(L to R): David Furr, Keri Russell, Brandon Uranowitz in Lanford Wilson’s ‘Burn This,’ directed by Michael Mayer (Matthew Murphy)

As we listen to Anna and Larry, we understand that Robbie, who was gay, meant a great deal to them. Anna’s anger with Robbie’s family, who refuses to acknowledge that he was gay or that he was a superb dancer (they never saw him dance) spills out in her ironic descriptions of the “relatives,” a Lanford Wilson set up for the next scene and a character revelation of Anna. We understand the easy dynamic among the three. We also note that Anna’s wry comments are her way of coping with Robbie’s loss and indemnifying the narrowness of the family who finds Robbie’s homosexuality unacceptable. The themes of familial rejection and estrangement over gender identity, and emotional disconnectedness with one’s inner feelings are themes that Wilson examines with rigor and truthfulness in Burn This, as he does in his other works.

Keri Russell gives a nuanced and calculated performance in Anna’s scenes with Burton and Larry. In this opening scene, Russell’s Anna modulates her emotions of anger and sorrow as she seeks affectionate relief from lover Burton, and an uplift from the humorous Larry, who comforts with irony and wit.

Larry’s lovably in-your-face gay ironist shares a closeness with Anna garnered during the years he and Robbie roomed with her. The quips and jokes adroitly delivered by Brandon Uranowitz’s Larry snap out and hit the bulls-eye. From his portrayal we understand that Larry speaks from deep within an authentic specificity born out of negotiating his gayness. His timing is excellent. Uranowitz provides the thrum of energy in scenes which, without him, might too readily have slipped away.

The hot-looking screenwriter Burton, a familiar presence in Anna’s and Larry’s NYC loft apartment (the back projection of the rooftops is stunning thanks to Derek McLane’s scenic design) rounds out the easy interplay among the three in the first scene. And as a straight man, Burton provides Larry with joke fodder.

David Furr’s portrayal succinctly conveys an upper level reserve and privilege that sits on the edge of narcissism. But he does retain a a bit of self-effacing humility and for this reason, Furr’s Burton manages to elicit our approval. He knows (perhaps Anna nudges him about this) that he must evolve and become a better “listener.” And for Anna’s sake, Burton reminds her that he is trying.

As two who appear to be the halves of one lovely, perfect whole in the best of all possible worlds, Anna and Burton are the beautiful, artistic, classy, cool couple. Boooorrrring! No wonder Anna is entranced by the strikingly opposite, frenetic, dazzlingly, off-beat Pale, even if he is as high as a cloud on cocaine and whatever else the restaurant manager has plied himself with. Though Anna has encountered Pale who “saves her” from pinned butterflies at his relative’s house after the funeral (you’ll have to see the play to understand the symbolism of this) “he” doesn’t register on her psyche. When he shows up to collect his brother Robbie’s “stuff” at the loft, Anna cannot help but “take him all in!”

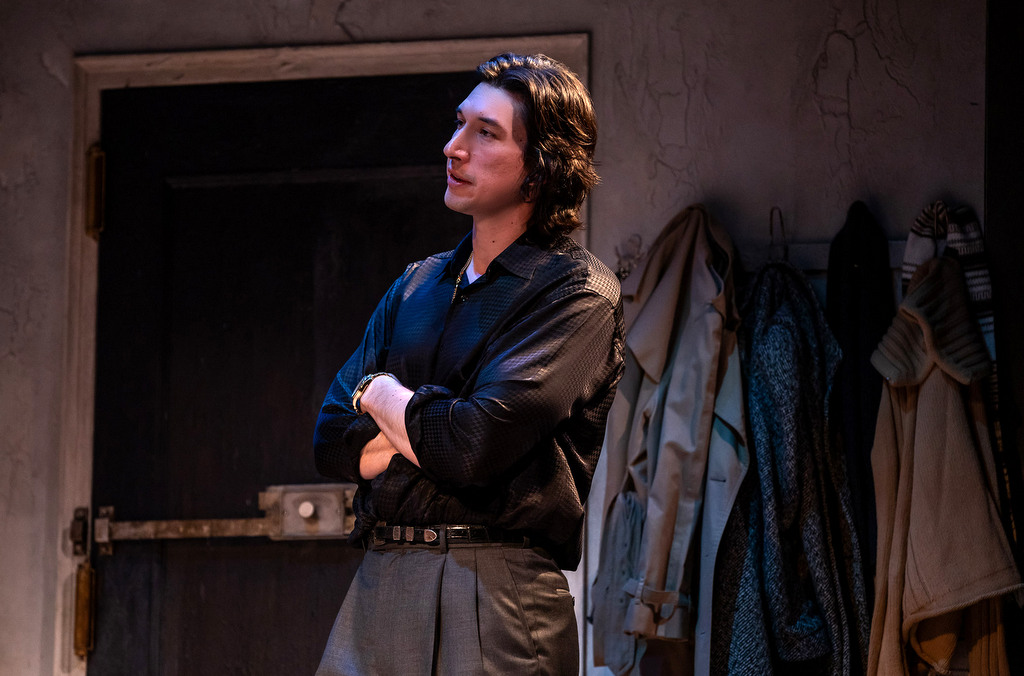

Adam Driver in Lanford Wilson’s ‘Burn This,’ directed by Michael Mayer (Matthew Murphy)

Adam Driver’s Pale explodes onto the stage in the second scene. Russell’s Anna never recovers. Neither do we. And that is one of the major thrusts of Mayer’s Burn This. Anna is so swept off her feet (as are most of the men and women in the audience) into the exuberance and thrall of his electric and fiery presence (he has a toaster oven in his belly), she doesn’t know what’s happening. Russell’s portrayal shifts; the nuance mediates then gyrates in the direction of surprise, disbelief and unrestrained engagement. Her gradual evolution as an individual morphs from this point. Wilson’s first scene with Anna, Larry and Burton provides the markers from which we measure her change from then on.

As Pale, Driver’s completely unaffected randomness and moment-to-moment outrageousness are jaw-dropping, in a funny, fabulous way. His unpredictability is life itself. Driver’s emotional portrayal lives onstage with sustained exuberance. Indeed, he resonates like a tuning fork. The magnificence of the vibrating sound thrums deep in our souls and hearts. His presence clarifies a message we need to follow. Be real if you find someone who moves you! (even on cocaine)

Is there such a thing as “love at first sight?” With regard to Anna and Pale, “sight” is the wrong word; perhaps “second sight,” is appropriate. Driver’s Pale is awesome; and Driver as Pale is starkly lovable. The irony is that externally, he cannot hold a candle to Burton. And that is the poetic Lanford Wilson’s second thrust which Michael Mayer’s direction relates with profound realism. Love is ineffable, perhaps irrevocable. It is as blind as the faith required to experience it, especially when you stumble in the darkness unprepared, then crash into it head-on!

After their intimacy Anna and Pale hunger for each other though they remain apart. But no matter. Pale is Anna’s spiritual counterpart, and she is his. Such a bond is not only chemical, it is profoundly healing and revolutionary.

How does Wilson engineer the redemption of these characters who remain separated, even estranged? Larry provides the gateway, manifesting another of Wilson’s themes. Friends (regardless of their gender and sometimes because of it) love and encourage without jealousy or fear of loss. Though this theme seems as obvious as climate change, sadly in the currency of our time, there are the “disbelieving” who find it anathema.

Kerri Russell in ‘Burn This,’ by Lanford Wilson, directed by Michael Mayer (Matthew Murphy)

Pale’s and Anna’s love and passion lift them beyond stasis, represented by Burton and Pale’s wife. Their tie seems other worldly, layered with truth and forgiveness. As a result, Pale acknowledges the lost years of his life as he confesses his frailties to Anna and the regrets he has amassed during his failed marriage and fatherhood.

For Russell’s Anna this love has encouraged her artistry onto a different pathway. She has entered into a new becoming. Unrecognizable to herself, unable to contain her emotional kindling fired up by Pale, she acknowledges the inner conflagration, a condition which she has never experienced with Burton. Pale acknowledges he, too, is completely overwhelmed. We understand this is a hard realization for both of them, a glorious disconnect/connect that will continue its wending way however it will. In the play’s last moments, Anna slips into Pale’s arms and life. He reassures her with love endearments, that only someone like Pale can express, and “cries all over her hair.”

Lanford Wilson’s characterization of New York City roommates’ gender diversity, and his themes about the ineffable qualities of love and generosity of friendship was revelatory in 1987, the setting of the play. Mayer’s production with the illimitable Driver, measured, blossoming Russell, with assists from Uranowitz and Furr is equally revelatory for us today. The themes of love, acceptance, the possibility of redemption and growth in this era of Trumpism are vital. They encourage us to retain the social advancements we’ve achieved and to embrace our humanity and decency through the power of non judgmental love and self-forgiveness.

Mayer and the actors and artistic creatives take this startling, understated, emotionally sonorous and uplifting play and make it a resounding success that you do not want to miss, especially for the laughter, the hope and the performances.

Special Kudos go to Derek McLane for scenic design, Clint Ramos, costumes, Natasha Katz for lighting design and David Van Tieghem’s sound design.

Burn This runs with one intermission at the Hudson Theatre (141 W 44th between 6th and 7th) in a limited engagement until Sunday, 14 July. For tickets go to their website by CLICKING HERE.