Blog Archives

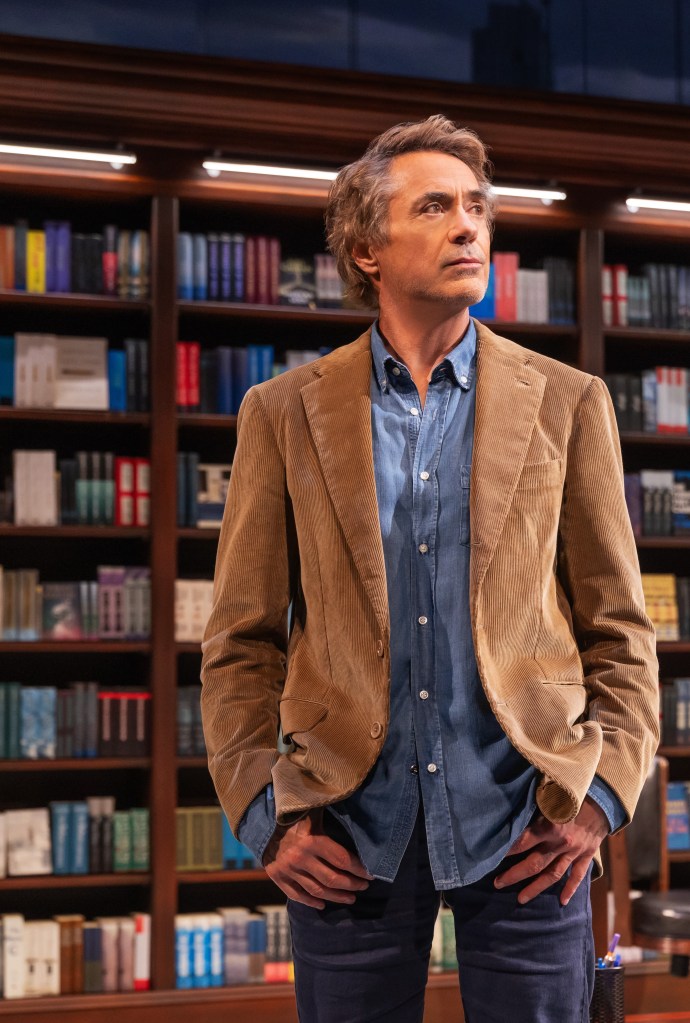

‘McNeal’ Robert Downey Jr. a Bravura Performance in a Complex Play

Posted by caroleditosti

McNeal, starring Robert Downey, Jr., is currently at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont. The drama by Ayad Akhtar (Disgraced), directed by Bartlett Sher, has sardonic/comedic elements. Akhtar’s work examines the successful writer Jacob McNeal under extreme duress at the pinnacle and nadir of his career and life.

As the play opens in McNeal’s doctor’s office, Doctor Sahra Grewal (Ruthie Ann Miles), reminds McNeal his relapse into drinking is killing him. From this point on, we follow the principal character on his downward journey into the abyss, after he wins the Nobel Prize for Literature. Throughout, McNeal literally and symbolically dies piece by piece, brain cell by brain cell, deep fake digital projection by deep fake digital projection. Thanks to the technical team, the digital designs and projections pop phenomenally. Indeed, they place us in the bubble unreality of Jacob McNeal’s imagination, where emotional grist rarely resonates.

Ironically, the discipline it takes McNeal to win the Nobel Prize for literature, doesn’t apply when he attempts to control his alcoholism. Indeed, a conundrum of side effects from a drug slated to help him stop drinking himself to death makes his life untenable. Addicted, he continues to drink bringing on side effects which include hallucinations, pain and thoughts of suicide. As McNeal bounces between self-loathing and overweening pride, we follow him deep into the bowels of AI assisted writing. Ironically, this hazard removes him further from himself and serves as the last straw which figuratively breaks his back.

Akhtar/Sher present the glorious image of McNeal as prizewinner giving his speech at Stockholm City Hall using video, then having McNeal step forward in his tuxedo to speak to us, the Nobel audience. After this climax in his life comes the downhill crash. The playwright removes the soul of the prizewinner’s art and exposes the ugliness. Elucidated by the technical team’s sets and projections, McNeal’s mind-bending journey strikes us with wonder, thanks to Michael Yeargan, Jake Barton and AGBO. Finally, Downey Jr.’s keenly woven, provocative interactions with women enlighten us to McNeal’s deep-seated toxic masculinity and admitted feelings of inferiority.

Throughout Akhtar’s interesting work, we experience McNeal’s calm, ironic self-annihilation. Numbly, we watch his digital-symbolic, self-destruction in front of witnesses/characters who don’t understand his destructive journey as they do battle with him. These include his son Harlan (Rafi Gavron), New York Times reporter, Natasha Brathwaite (Brittany Bellizeare), and his former mistress, Francine Blake (Melora Hardin). These are shadows of individuals without definition which McNeal, in a brain fog, uses to pick ax his soul. Will anything be left of him after he finishes?

With sardonic, arrogant aplomb, McNeal rationalizes and accepts himself as a fraud. During each of his interactions, he charmingly employs his antic self-loathing to dismantle himself and drive through to his core truth. Through Robert Downey, Jr.’s fine performance we understand McNeal’s disgust, his masochism and self-betrayal, masked by ego, charm and pride. McNeal may have fooled the world to give him a prestigious prize, but he knows better. He cannot fool himself. And what he seeks he eventually attains by the conclusion.

On top of McNeal’s neurotic struggle to “set things straight,” we learn in horror (the writers in the audience, anyway), about his penchant for writerly duplicity. Like a kleptomaniac (a writer’s klepto), addicted to theft, we learn through his confrontations that McNeal engaged self-destructively in plagiarism to achieve his success.

However, plagiarism increases his feelings of inferiority. And it promotes a twisted cycle of repetition. We learn through Harlan’s and Blake’s attacks that McNeal stole from his son’s friend, his wife’s bad novel, Francine Blake’s life, etc.). With these he creates his successful but basely unoriginal works. All of this occurs not without consequence. For he turns from his successes and belittles his creative talent. Ironically, the plagiarism reaches an apotheosis of fraud when he employs the inferior AI program CHAT GPT. Combined with his self-immolating interactions and the drug’s side effects, his use of the program pushes him over the edge. Jake Barton’s projections fantastically convey this as he vomits up stolen words projected on the stage floor.

Interestingly, we see how he employs CHAT GPT in an earlier sequence. Inputting literary works from Shakespeare, Ibsen, Kafka, Sophocles, Flaubert, etc., he examines concepts to explore. Then employs the program to convert these inputs to the style of Jacob McNeal. Each use of GHAT GPT increases his soul sickness.

Sadly, with the exception of his doctor and his agent Stephie Banc, the always wonderful Andrea Martin, no one knows he’s dying. In a strange self-satisfaction he is comforted that the other characters, especially his son, find him as loathsome as he finds himself. Thus, they can offer little comfort which he wouldn’t accept anyway.

In the last scene, McNeal confides in his audience eloquently after striking layers of his fraudulent self against the sharp criticisms of his son, the reporter and Blake. Only then does he attempt to speak in his true voice. But once more, he applies AI, this last time inspired by Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. How can we trust his narrative? Does anyone reliably, truthfully relate their own story? Robert Downey, Jr. makes a convincing case for our straddling the fence of incredulity, then leaping into the last artifice with him.

Bartlett Sher’s integration of the digital imagery and projections to illuminate McNeal’s imagination and world is spot-on. Likewise, the ensemble, integral players in McNeal’s journey through self-torment, charges the play’s energy. Robert Downey Jr.’s sustained performance gives one pause and intrigues as Akhtar’s confounding character, McNeal.

Though the playwright uses AI as an object lesson and/or bête noire, more importantly, he reveals the kinds of writers who might employ it and why. Lastly, the tragedy becomes that McNeal separated himself from himself in alienation. AI also becomes a symbol or instrument of death, the death of creativity and originality, despite McNeal’s clever justifications for using it.

McNeal runs one hour forty minutes with no intermission at the Vivian Beaumont. It’s a pleasure to see Robert Downey Jr.’s superb performance. https://www.lct.org/shows/mcneal/

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

‘Corruption,’an Important Play at Lincoln Center Theater, Mitzi E. Newhouse

Posted by caroleditosti

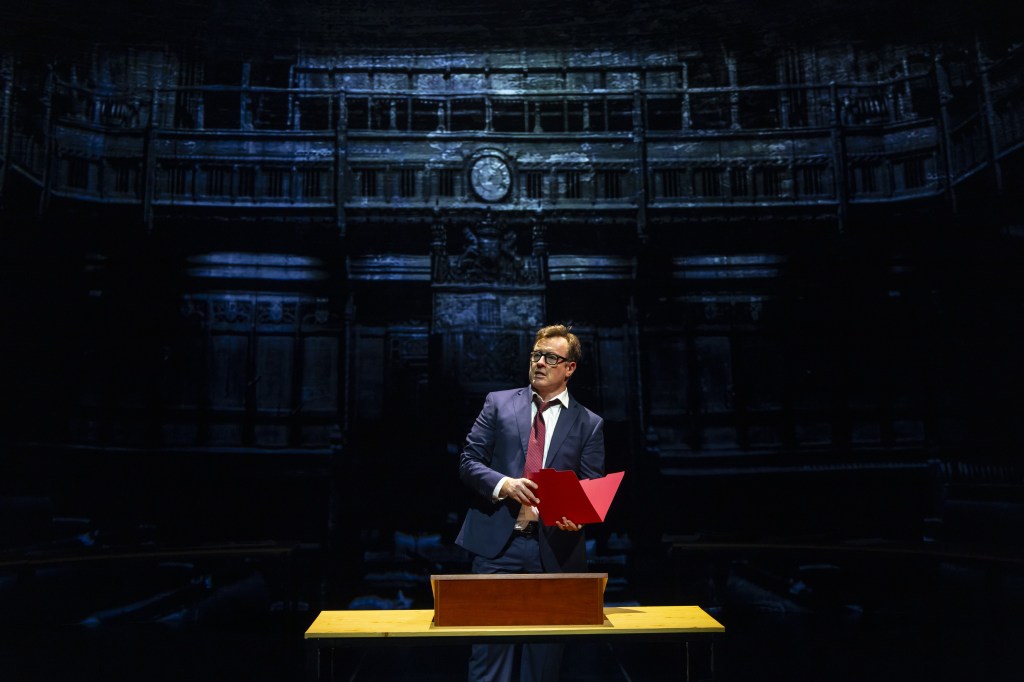

Corruption‘s well paced reimagining of the UK phone hacking scandal involving Rupert Murdock’s News Corp. empire is written by JT Rogers (Oslo) and directed by Bartlett Sher (Oslo). The hybrid drama/comedy is enjoying its premiere off Broadway, Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse. Rogers’ epic chronicle exposes key individuals employed by News Corp who follow a dangerous ethic: the ends justify the means. These media players believe that corporate profits legitimize any deleterious impact the media may have on the victims they exploit.

In the era of US fake conservative news, Roger’s two act play trenchantly reminds media consumers that malignant CEOs of companies monopolize and weaponize power and influence to oppress human rights. Ultimately, they direct global political affairs to their profitable advantage. Even if the companies harm the populace, and there are lawsuits, in the corporations’ ethos, it’s OK as long as the bottom line is not irreparably damaged. Corruption reveals that there are always ambitious and warped lackeys at the ready, like Rebekah Brooks (the excellent Saffron Burrows), who may engineer or accept malign acts for the company’s betterment.

Based on Tom Watson and Martin Hickman’s book Dial M for Murdock: News Corporation and the Corruption of Britain, Rogers’ play is an exhaustive and detailed examination of the players and insider events which reveal the cover up of News Corp’s employees illegally trashing the privacy of 11,000 citizens. These not only included celebrities. Reporters used “information” illegally sourced from politicians and ordinary people alike. With this material reporters sensationalized stories for maximum shock value. When they couldn’t get enough truth or facts to fill a teaspoon, they made up lies out of whole cloth.

During the unspooling of the play’s events, we learn that no one was considered too great or too small to smear and damage, as long as the effect produced was eyeballs glued to the tabloids, specifically “The News of the World” headed up by Rebekah Brooks CEO of News International.

The play is at its edgy, sharp best when Rogers dramatizes the conflict between key adversaries Rebekah Brooks (Saffron Burrows), and Tom Watson (Toby Stephens), as well as their allies and foes. For Brooks, problematic allies she manipulates are legal counsel Tom Crone (Dylan Baker), and Rupert’s son, James Murdoch, (Seth Numrich) in addition to Prime Minister Gordon Brown (Anthony Cochrane). For Watson, major allies include Martin Hickman, friend and reporter for the Independent (Sanjit De Silva), the lawyer representing hacking victims, Charlotte Harris (Sepideh Moafi), and Siobhan, Watson’s wife (Robyn Kerr).

There are forty-six characters portrayed ably by thirteen actors. Rogers sacrifices in-depth characterization, in part, to relay the sweeping phone hacking story that energizes his themes. In the forefront is the imperative that a free, vital press, unhampered by a company’s profit motive, is essential to produce the facts and information which enable a democracy to function. That way citizens can make informed decisions to improve the social good and hold bad actors to account. However, to receive such news and information, the populace must be educated and knowledgeable. It is up to them to reject a diet of calumny, lies, and sensationalistic fabrications that support anti-science “the earth is flat” stupidities, and “in your face” political propaganda and nihilism.

Escapist tabloid journalism which exploits the “sickness” of others in a voyeuristic display to make the reader feel better with their lot, capitalizes on the lowest bar in human nature. Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp revels in feeding the populace trash for high profits, then projects that citizens are to blame for demanding such fare. This is an affirmation that the character Rebekah Brooks suggests at the play’s conclusion. In her final commentary, she justifies the necessity of The News of the World with a presumption that without the tabloids’ profitable journalism, there would be no other journalism. “The

profits from my papers allow the papers you read to exist. There is no journalism without my journalism.”

However after careful consideration Rogers’ Corruption shows that Brooks and Murdoch’s tabloids and his faux “news” empire normalized indecency, negative propaganda and lies in order to control and gain power. The playwright’s overriding question is whether Murdoch and Brooks truly provided a necessary service or negatively frayed the social fabric of goodness because of their own greed and rapacity.

The play opens at Rebekah Brooks’ wedding reception, where Rogers introduces the ambitious woman that Rupert Murdoch trusted to make him money. In a private room, newly appointed head of News Corp UK, James Murdoch, and Brooks go head to head. They argue about the direction of News Corp’s future. James Murdoch asserts that the print division barely makes money. From James, we learn that Brooks has clawed her way through the ranks to be editor of The Sun, a powerful position which gives her equal footing to counter his arguments.

Numrich’s Murdoch states that technology, digital media, and TV are where News Corp will be in the future because print journalism is a relic of the past. Brooks argues that her print division fuels all other journalism. At the end of the scene James Murdoch congratulates her on her new appointment as CEO of News International. Father Rupert Murdoch trusts her with the responsibility of continuing the profitability of all the Murdock tabloids. She will not let papa down.

Throughout the play, Rogers highlights the nefarious brilliance of Brooks who maintains the efficacy of the scurrilous tabloids and stops at nothing to ensure they add to the soaring profits of News Corp. No wonder why old school Rupert Murdoch loves her more than his son, and does everything to keep her near, even after the scandal blows up in their faces.

In attempting to cram in salient details, Rogers keeps scenes short. Sher directs the action at a seamless, brisk pace with minimal set design by Michael Yeargan. The tech crew interchanges and rearranges tables between scenes to provide the change of setting and atmosphere of alacrity. The staging reflects the rapid and shifting state of the “news” media, hyped up on digital steroids. It predominately features multiple TV screens onstage and at the top of the proscenium. The screens show various news clips and shows during that time. The blinking screens are purposefully a distraction from the dialogue. When text messages are posted, we see the quotes projected on the back wall via 59 Productions projection design.

Ironically, with the media constantly flickering at us, the audience becomes numbed to the visuals and eventually ignores them. One of the takeaways of Sher’s staging is that the media overload we are expected to negotiate and be aware of on our phone screens numbs us and in fact dulls our awareness. It becomes harder to keep up or understand the complexity of events that are reduced to a few words of soundbites and quickly edited visuals. Without that complexity of understanding, facile, wrong opinions are formed and judgment is skewed toward the superficial assumption and wrong conclusion.

Companies like News Corp rely on tabloids to offer a contrast to the in-your-face screens which mesmerize and numb. The tabloids give the reader the semblance of “controlling” the information that they have bought in print. However, the opposite is true and, as Rogers’ drama proves, the tabloids are filled with mostly exploitation pieces that masquerade as factual and realistic. Understanding and depth are sacrificed for the superficial and shocking.

During the the first act, we note Brooks and News Corp’s power. Brooks gently threatens Prime Minister Gordon Brown to fire Tom Watson (his labor MP who has been his hatchet man). She warns Brown that the story she is releasing about Watson will create havoc and implies if Brown doesn’t get rid of him, it may take down the Labor Party and Brown with it by association. Brooks jokes that Brown is “running the country, isn’t he?” Indeed, maybe he isn’t, if Brooks is leveraging lies to force Brown to fire Watson.

Brooks wields tremendous power as a kingmaker and king breaker. She operates with impunity, because no one has the courage to investigate or litigate against “The News of the World’s” defamation, lies, calumny and payoffs. We learn the tabloids’ shock and scandal value are critical to blackmail. Brooks and the tabloid intimidate almost everyone who is anyone in the culture and society of the UK.

Watson confronts Brown about Brooks’ political hit job. Sher has the actual headlines projected on the backstage screen, “Treacherous Tom Watson,” “Mad Dog Trained to Maul,”etc. Brown soft pedals Watson by saying no one believes the lies that Watson “registered pornographic websites under other politicians’ names.” However, Brooks doesn’t retract the lies as other UK papers do. Siobhan, Tom’s wife, insists that Tom lay low in parliament and say nothing because she is tired of the negative PR and the outrage and stalking that has hounded them and terrified their son. Watson quiets down in parliament in the next scene and we see how Brooks gets her way now and in the future when News Corp backs the Tory Party candidate James Cameron to win.

Though Brooks has sucked the life and power out of Watson, he sues and his fury converts to action as he teams up with his friend Martin Hickman from the Independent and other allies after learning the police quashed an investigation into phone hacking. Brooks and Andy Coulson, the heads of News International disavow any knowledge of the hacking, despite documents that link hired investigator Glen Mulcaire’s (Dylan Baker), illegal acts to News International reporters.

The fact that only Mulcaire goes to jail while Andy Coulson is promoted to director of communications for David Cameron and the Torys spurs Watson and his team to apply pressure via Twitter, blog posts and other social media questioning why the police backed off the investigation. Not only do they elicit the help of a wealthy individual who had been hacked and slimed, eventually, they pull in the New York Times to cover their story. Watson’s team brings into view how Brooks and her cohorts have destroyed the lives of ordinary citizens and caused destruction and misery for profit.

In the very long first act which is expositional, perhaps some of the details and/or scenes may have been edited and reworked. The second act moves quickly to a satisfying resolution as The News of the World, Coulson and Brooks are held accountable. However, the punishment is a mere slap on the wrist for Coulson-four months in prison. Brooks is found innocent of all charges. Though Murdock closes down Brooks’ tabloid, after a time, she is keeping things humming elsewhere.

When the question arises, what did they all go through hell for, it is Watson’s wife Siobhan who encourages Tom to continue to stand up for the truth. Only with persistent fighting against the maelstrom of lies will the truth ever be seen. One can only hope.

Corruption is an important play about the Murdoch empire that reveals how News Corp steamrolled through the UK first to gain extraordinary power which then was used to blossom evilly in the US. Leaping across the pond News Corp’s malignant MO impacted the 2016 US presidential election by helping to install the incompetent, unqualified, Donald Trump as president. His negligent, derelict actions during the COVID-19 pandemic had serious global economic impact and social repercussions that many countries are still reeling from today.

Fox News in the US perpetuated Donald Trump’s making COVID-19 a political crises. Tragically, this political emphasis actually spread the contagion and made it difficult to ameliorate, especially in the southern United States. If the UK had acted to contain News Corp and hold it accountable with massive financial fines and more severe punishments, it may have paused News Corp’s Brooks, Coulson and others and curtailed its power and influence in the US

Rogers raises important questions in Corruption. What price do we pay for the decency and dignity of privacy? For those who violate our right to privacy, shouldn’t the punishment be severe because it is a crime of violence on our persons, a metaphoric rape and humiliation, especially if the citizens are not celebrities getting paid for their fame?

Though the play has infelicities, the acting, direction and pacing allow the themes to shine. It is these in our time that resonate most fiercely, especially as we face the AI fabrication of photographs, voices and more.

Corruption. Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse. The play is two hours forty minutes with one intermission. https://www.lct.org/shows/corruption/schedule/

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

‘Camelot’ Revival at Lincoln Center, Superbly Re-imagined for Our Time

Posted by caroleditosti

The original 1958 musical Camelot. performed with Alan Jay Lerner’s book and lyrics, and Frederick Loewe’s music, adapts theArthurian legend from T.H. White’s collection of fantasy novels entitled Once and Future King (1958). White’s adaptation was loosely based on the 1485 work Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. Aaron Sorkin’s book updates the musical and puts an interesting spin on the events of legend, heightening the characters and shifting the emphasis to King Arthur, superbly portrayed by Andrew Burnap (Inheritance). As a result, Sorkin diminishes the love affair between Phillipa Soo’s Queen Guenevere (Hamilton) and Jordan Donica’s Lancelot du Lac (My Fair Lady), aligning it more with romantic tradition which fails. With outstanding set design and fine direction by Bartlett Sher, Camelot is a stunning revival of symbolic political moment, currently running at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont until September.

At the top of the play Sorkin introduces us to one of the most important aspects of Arthur’s kingdom, the feudalistic power structure and Arthur’s previous isolation from it. Before we even meet Arthur, we meet the lords who serve the king and make up his court, as well as Merlin (Dakin Matthews), Arthur’s counselor, whose wizardry is seen through his balanced demeanor, wisdom, erudition, time transcendence, foreknowledge and keen ability to redirect the perspectives of less enlightened individuals.

Tasked to meet Arthur’s bride-to-be at the top of the hill near the castle, the lords exclaim that her carriage is at the bottom of the hill. We note Merlin’s attributes in his initial discourse with these three knights, Dinadan (Anthony Michael Lopez), Lionel (Danny Wolohan), and Sagramore (Fergie Philippe), who rant that the Guenevere’s carriage has gone against tradition, as they watch her disembark from her carriage far away from them. This change in tradition upsets them, until Merlin uses gentle wisdom to calm their responses and show them they can merely change the law to update tradition. This exchange among the knights and Merlin indicates the conflict to come, tradition vs. progress. The knights’ acceptance of Arthur’s changes is paramount to Camelot’s success.

The ruling elites are conservative traditionalists. But Merlin handles them easily and emphasizes the power of laws to change useless, outmoded ways of being. These men have power and influence over an unequal class system, institutionalized by feudalism (the peasants who serve and the lords who protect and luxuriate over them). Arthur must step around them and gain their trust to overturn traditions which have harmed and caused wars and bloodshed.

Not a member of the royal class per se, Arthur must navigate the knights’ entrenched power with wisdom, if he is to rule his kingdom well and remain effective. This not only requires steadfast courage and acute psychological and personal skills, it demands a political philosophy and will to unite the lords and prevent division. Additionally, training and counsel from Merlin, whose extraordinary gifts of wisdom provide a broader, endowed perspective and understanding, are a boon.

In Sorkin’s different spin of Merlin, we understand that the time has been stepped up one hundred years, so that the medieval age is coming to a close, and Arthur is pushing his kingdom in the direction of the Enlightenment with the help of Merlin. Unfortunately, Merlin’s assistance remains all too brief. After his death, he is replaced by one of the oldest knights in the kingdom, Pellinore, also portrayed by Dakin Matthews, who Guenevere invites in to their circle.

Sorkin advances Arthur’s human graces, contrasting them with the backward knights of his time, who he must manipulate against their own stupidity, which manifests in Act II, encouraged by Mordred (Taylor Trensch) in “Fie on Goodness.” Arthur is not a royal in arrogance, presumption or privilege. He is a people person, decent, kind, likeable and extraordinarily generous. He is more like a Christ-like figure, who forgives Guenevere and Lancelot’s “treason,” and refuses to brutally punish them for their lack of faithfulness.

He invites his son Mordred into his circle, as a reconciliation for his past abandonment, which his mother caused by refusing Arthur’s pleas for her to come and live in the castle. He announces to the kingdom that Mordred is his out-of-wedlock son who is being treated equally like everyone else and has the opportunity to learn and become a knight, if he wishes. But Mordred refuses to listen to Arthur’s explanations why he is not with Morgan le Fey (Marilee Talkington), and he gives lip service to Arthur’s largesse. Instead, Mordred manufactures his own victimization and weaponizes it against his father. Indeed, as the villain, Mordred exploits Arthur’s kindness and love. In his wicked world, these traits are a weakness to set up Arthur’s downfall (“The Seven Deadly Virtues”).

Especially in the characterization of Arthur, Sorkin presents the idealization of a king whose humility, love, intelligence, forgiving nature, and equanimity is all that the Enlightenment promises. Unfortunately, Arthur is a man out of his time, more an influence for future generations in inspired legends and stories of his exploits, frailty and kindness, which can guide by example to bring hope and light to others. Though his reign and Camelot only lasted for for a brief time, the antithesis of the stability and “happy ever aftering” Arthur and Guenevere sing about in the beginning (“Camelot”), is mythic. All individuals, even the current day audience can aspire to Arthur’s ideals of a place of congeniality for persons great and small.

Each of the characters we see immersed in feudalism are lesser in nature, greedy for power, brutal, judgmental, calculating and self-absorbed. In the dialogue to some of the songs, we note Sorkin cleverly magnifies this. For example in the ironic “Simple Joys of Maidenhood” that Guenevere sings about wanting knights to die and sacrifice themselves for her love, Arthur brings up the notion that this isn’t much fun for the knights. Not only is Guenevere naive, she is brutal in her unrealistic romanticism, a clue to the source of her treachery with Lancelot, spawned from her privileged background. Indeed, the same knights that would kill for her, would just as soon end her “maidenhood,” in a rape, which Arthur seems to note in his ironic comment, but Guenevere conveniently ignores.

Guenevere is a traditionalist in all of her “modernity.” A spouse by arranged marriage to prevent war between England and France, she is born of royalty and has the presumption, lack of humility, and fieriness to prove it. Her expectations are royal, and she doesn’t understand Arthur’s personality and hoped for kingdom. Initially, she presumes Arthur will behave according to the traditions of kings, like her father. Kings are sexually promiscuous. They treat women as objects for their pleasure; they make demands on them, requiring they be passive creatures without individuality or autonomy.

That Arthur doesn’t have women at his sexual disposal at court, and expresses belief in the fidelity of marriage is a striking and revelatory contrast. Additionally, he fosters the novel idea they must prevent fighting, war, bloodshed, abuse of the lower classes and women. Remarkably, he gladly accepts her input of ideas. It is during their discussions that the “knights of the round table” come into being. In this acceptance of Guenevere as his ruling partner, he reveals that he is dynamically striding toward enlightened governance.

Appealing to her better nature constantly, Arthur trusts her with Lancelot. Ignoring her suggestion, he refuses to expel the narcissistic knight from the kingdom, before they have their momentary affair, which Mordred has “encouraged,” unbeknownst to Arthur, Guenevere and Lancelot. Above all, Arthur provides her with freedom and power to rule with him. This is unlike anything that is supposed to happen to a female royal anywhere. And in the musical’s memorable signature song, he imagines his vision of Camelot in order to engage her to want to be Queen, and woo her, before she knows his identity.

In retrospect, at the conclusion of the musical, we learn it is his intentions of good will toward her that prompts Guenevere to fall in love with him early on. However, since both of them are unpracticed at love, they never express it to each other. It is one of Arthur’s chief weaknesses of pride. Ironically, he fails at his own express thoughts in “How to Handle a Women,” and doesn’t love her, so that she understands his love, understands that his freedom and trust in her are love, decency and generosity in the Arthurian time of patriarchy on steroids. She is still stuck in the romantic notion of love, reinforced by her ladies in waiting, who push romantic tradition on her to her detriment.

Sorkin’s book is deeper and more complex than the original musical, so that before each song, one must catch the nuance. For example the humorous repartee before and after the song, “Camelot,” works beautifully and heightens the ironic, fantastical lyrics, symbolizing the fickleness of the place in its hyperbole, “The snow may never slush upon the hillside, by 9 P.M. the moonlight must appear.” In expressing his metaphor, Arthur encourages Guenevere to realize he is unlike royalty, and his kingdom and reign with her will be unique, maverick, loving. The tragedy is that the depth of their love is unrealized and misunderstood. Guevenere, entrapped by the tradition of her place and status, and Arthur overwhelmed by his sense of inferiority to express his feelings to her, contribute to the fall of the kingdom.

An express, underlying irony is that Arthur’s view and behavior toward women is even more forward thinking than many in the US South today, and especially some of the GOP political party antithetical to equanimity between women and men. Thus, Arthur is not only schooling Guenevere about equanimity and generosity as love, he is also reminding the audience of the beauty of such an approach between men and women for our own time.

Of course, this is legend, and it is hard to come by in reality, which makes the final exchange between Arthur and Guenevere, and their relationship, all the more poignant and tragic. In a failure of her character and bondage to her identity, Guenevere is too late to recognize and receive Arthur’s love and freedom to express it. Instead, she opts out for fleeting passion which is another form of bondage, and is the antithesis of freedom. It is why she regrets her affair with Lancelot, does not run off with him, but goes to a convent. The rest of her life she does penance for contributing to his death, Lancelot’s death, and the destruction of the kingdom.

Phillipa Soo and Andrew Burnap are perfectly cast in their respective roles and are simply smashing in voice, authenticity and aura, making us empathize with their characters who are victims of their own frailties. Burnap, especially at the conclusion, coalesces the poignant tragedy that Arthur’s dreams are broken, and that by a combination of rotten timing, privileged selfishness (by royals Lancelot and Guenevere), bitterness and resentment by an ungrateful Mordred, he is undone and must pay the forfeit with his death.

Jordan Danica’s Lancelot is both funny and dangerous, for we know what is coming when his resistance to Guenevere “protests too much” in selfishness. The right way to serve King Arthur would to leave and escape his lust, which he can’t because of his own self-betrayal. The bedroom scene is perfectly directed to suggest the thrill of passion, but not love. It is appropriate that their “aftermath” falls flat in disgrace, as they realize the import of what they’ve done. Sadly, as the pawns of Mordred, they’ve betrayed their king, and the golden idea which elevated their lives and the kingdom. Interestingly, Donica’s “If Ever I Would Leave You” indicates he can’t leave because of how she “looks” in the changing seasons. If he really loved her, not the image of her and him together, he would have left the moment he sensed the attraction to save her and himself. So much for his boasted purity. To insure his leaving, he would have been truthful with King Arthur. Donica’s voice and interpretation of that song in particular are non pareil, just fantastic.

Sorkin mitigates the “magical” in this Camelot update, palatably. For example it is suggested Arthur is able to pull the sword Excalibur out of the stone because previously, ten thousand men loosened it. Lancelot’s “resurrection” of Arthur occurs because he was just knocked unconscious and not killed. No miracle occurred. Arthur’s characterization is a forerunner of the rational man of the Enlightenment, when Europe will experience many transformations. Then, rigorous scientific, political and philosophical ideas burgeon in the society with the rise of the middle class. In his approach to ruling his kingdom, Arthur is bold to overthrow the most noxious elements of feudalism to bring ideals of equanimity, peace and honor that “might for right” and “justice for all” are the better way.

The thoughtful production has humor, vibrance and poignance. The treachery and resentment of unforgiving Mordred (the fine Taylor Trensch), who helps explode the Camelot ideals of equanimity, peace and honor are a potent reminder that such a “heaven on earth” is impossible because of human fallibility. Thematically, the musical warns us that only in the aspirations of future generations, represented by Camden McKinnon’s Tom of Warwick, may that possibility become reality in limited circumstances.

In the meantime, hope must be kept alive for a time when such dreams are possible. Realistically, all the characters fall from their own grace. It happens with the best of individuals, who cannot govern their own passions, and with the worst who rebel against a more perfect order for the sake of power. Sorkin reminds us in this complex re-imagining that most important is the striving for equity and equilibrium, not the achievement of it, which in itself is too fantastic to sustain. In the striving is the learning and revelation which is priceless. As such they provide the way for the hope of tomorrow, arriving at democratic polity hundreds of years in the future: i.e. a democratic Ukraine in the face of genocidal aggression by Russia, a democratic United States in practice not in lip service.

The sets by Michael Yeargan are suggestive, stylized, minimalist and symbolic, perfect for scene changes to the castle, Arthur’s study, a maypole dance, the tournament and more. Noted the black tree on stage never blossoms or has leaves, regardless of season. At one point the projection of the beautiful Camelot is seen in the distance. However, the tree does have leaves on the program cover as a figure peers out from its branches, and we, like him, wait for a “more perfect union,” and peace, justice and equity for all.

Jennifer Moeller’s costumes are richly appropriate and gorgeous. Lap Chi Chu’s lighting design, Marc Salzberg & Beth Lake’s sound design, Cookie Jordan’s hair & wig design cohere to manifest Bartlett Sher’s vision. Projections by 59 Productions are, as usual, marvelous.

I had forgotten how lyrical, memorable and powerfully touching are Lerner and Loewe’s songs and music. “Guenevere” is heartbreaking. Special recognition goes to Kimberly Grigsby’s music direction which does justice to the score. Noted are the original orchestrations by Robert Russell Bennett & Phillip J. Lang, and dance & choral arrangements by Trude Rittmann. These artists, no longer with us, had a prodigious history of creating the beauty of Broadway (Bennett over 300 productions, Lang and Rittmann over 50 productions). Byron Easley’s choreography is energetic in “The Lusty Month of May.” B.H. Barry’s fight direction and the staging/choreography of swordfights of Lancelot proving his mettle with the three knights and Arthur, appear as dangerous as the crashing blades sound.

Camelot runs with one intermission. Every minute is worth seeing. Don’r believe some of the critics. Judge for yourself. For tickets and times at the Vivian Beaumont go to their website https://www.lct.org/shows/camelot/

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

‘Pictures From Home,’ Strong, Humorous, Heartfelt Performances Bring Depth and Nuance to Must-See Theater

Posted by caroleditosti

How does one negotiate one’s upbringing as an adult, when one’s parents still keep them under their charge and supervision as a comforting mainstay of their relationship? How does one one respond, if the parents in their relationships with adult children default to roles of superior authority figure vs. inferior minor? The superb Pictures From Home raises and answers these questions.

Pictures From Home in its premiere at Studio 54, currently runs until April 30. Written by Sharr White (The Other Place), and directed by Bartlett Sher (To Kill a Mockingbird) it sports a tremendous all-star cast who inhabit the characters to the cellular level. The play, which encapsulates photographer Larry Sultan’s decades-long project, exploring his relationship with his parents through pictures, is a knockout. Based on Sultan’s titular photographic memoir (1992), White’s work unfolds as an intimate portrait of a family that challenges the audience to think about how we reconcile issues with our own parents that we know may never be resolved.

White’s depiction of Larry (portrayed with great sensitivity and aplomb by the marvelously versatile Danny Burstein) and his parents, as a memory play is largely thematic. The son, Burstein’s Larry perseveres in his project initially to learn about his life and relationship with his parents through the post-war pictures taken before and after they moved to Southern California. Of course his initial intentions change with the passing years he gets to know his parents from a different viewpoint.

In his quest to understand levels beyond surface identities, Larry chronicles the culture against the backdrop of family photos, videos. discussions and interviews during weekend visits (twice a month) from 1982-1992. Importantly, Burstein’s Larry discovers that the process of “information gathering” itself is wondrous, life-affirming and loving. He learns to live with the uncertainty that the truth about his and his family’s past and present is always shifting. Eventually, he realizes that this is an acceptable revelation that occurs despite his creating frustrations and annoyances for his parents and himself. Complications arise, as he explores other perspectives about them through what he hopes will become a “more objective” lens.

However, throughout the humorous and at times rancorous give and take sessions among son Larry, Dad Irving and Mom Jean (the inimitable Nathan Lane and Zoë Wanamaker) there is the inevitable acknowledgement that this is “their” family. For good or ill they have navigated the emotional and psychological shark infested waters and stuck by each other protected by an abiding, scratchy, blanket of love. Who is anyone to judge them? There’s a quote about glass houses and throwing stones somewhere in this production which White, the actors and director take out and shake up with chiding humor to “not point the finger too readily or heartily.” Judgment doesn’t apply, regarding this intimate enlivened portrait; in fact, it is disingenuous.

Indeed, we cannot look back in hindsight and determine accurately, Sharr White suggests as one of the themes of this clever production which sneaks up on you, if you allow it the grace to do so. At it strongest moments the presentation of the family dynamic, becomes like watching our own family dysfunctioning in real time. Larry’s motivations and intentions as he seeks out Irving’s and Jean’s approbation, insights and perspectives, and weathers his father’s criticism during the unfolding of the project, are right out of our own home movies. Not only are the interactions hysterical and funny, they are heartbreaking and identifiable, and at times searing.

If one is fortunate to have family, it is what all adult children (if they are honest) cannot really grasp in the fullness of its significance and meaning to their lives. We can’t even securely attribute our successes or failures to them because there is the ineffable mysterious that cannot be pinned down. And if one does attempt to acutely define what is undefinable and cover it with blame or calculation, it will be incomplete, misaligned and skewed by one’s own biases. Family relationships in all their warts, impurities and embarrassments are beautiful because they are attempts to get it right, Sharr White teases out of Larry Sultan’s photo memoir. The heartbreak of Larry, Irving and Jean is that with every imperfect interaction, they don’t quite hit the mark. That is the pain and that is the glory. At least they tried.

And just as Burstein’s Larry concludes by the end of the play (and project) and we concur as an audience watching the intimacies of what the photos reveal, family relationships, individual and combined, are infinitely complex. In that complexity, if grace is attempted, there is mirth in the clown car of family gatherings. You have to laugh. If you don’t find the humor, you weep, and of course in the humor, there has been much weeping and pain to allow it to rise to the levity of wit and wisdom.

As Larry explores and unravels each home movie or picture, discussing it with Jean and Irving, he chooses to accept and love as his parents have and still love, despite the sorrows and pains. Underneath there are happinesses. And this is a treasure worth more than the profits that Larry gains when he publishes his photo memoir which receives wide acclaim and Irving’s praise and the relief that his son’s visits have accomplished “something worthwhile.” The time spent with his parents and their generosity in allowing him to needle and prod them could never be fashioned any other way. The bond they form holds no regrets because in due season, as Wanamaker’s Jean underscores in the poignant scene with Burstein’s Larry, she can’t live forever, though in his child-like heart he wishes she could.

Of course we “get” her question to him, “Why would I want to?” That one of the reasons why Larry might be doing this project, to redeem the time with his parents, turns out to be his finest reason for its accomplishment. Wanamaker and Burstein render every nuance and feeling out of their scene together which is lovely and outright smashing.

Thomas Wolf proclaimed in You Can’t Go Home Again, that you can’t return to the past, for time’s momentum dissolves what was into inaccurate memory. Likewise, there is something greatly tragic in viewing photographs to jar one’s memories and find meaning which can never be fully realized. For the faded photographs often capture a brand, a statement to cover over truths with impressions. However, as a photographer whose life is made full attempting to capture timeless compositions, Burstein’s Larry eschews Wolf’s adjuration and tries to discover meaning and substance from the impressions. And he doesn’t quite succeed to his liking, yet it is magnificent that he tries.

Time and again he visits Jean and Irving, flying from his professorship, wife and children to his old homestead in Southern California (neatly effected by Michael Yeargan’s set design). As he interviews his parents and reviews again and again various photos from his childhood to capture the cultural zeitgeist and look for new interpretations of his life and parents beyond his memories from a child’s perspective, he concludes points, then argues with his father who disagrees with him. Ingeniously, he examines and reflects upon their poses, facial expressions, gestures, activities, captured in the still point, directing his parents toward a new interpretation. It is a humorous fact that the photos Larry selects for his book are precisely the ones that his parents and particularly his father dislike because they are not posed to perfection or portray a flattering image.

In the dialogue centering on the photos,White has given the actors the grist to take off into the amazing territory of nuance to bring out sub rosa emotions, defense mechanisms and disclosures from each family member. That Jean is not as forthcoming as her husband, but is nurturing and supportive of her son speaks volumes. She is wary and deeply loves and understands her husband’s weaknesses and defensiveness, though she gets fed up with him at times. He counts on her understanding and is the one to affirm his love for her toward the conclusion.

Through each of their interactions that represent the many visits from Larry, White creates vignettes that are thematic. In one when Lane’s Irving hysterically hobbles about with an injury we never learn how he received, the scene moves to an unexpected and poignant end-stop about aging. Lane’s Irving effects the emotional arc of the scene with incredible moment and a cry from the heart that is tremendously moving.

In another interaction Jean’s growing dementia is subtly revealed in her panic about where she put various items. From the beginning of the play to the conclusion, Wanamaker subtly reveals Jean’s worsening condition. If one is not focusing, one might miss this incredible aspect of her performance. Wannamaker reveals Jean’s memory decline, nervous fidgeting and sometime irascibility, which Lane’s Irving discounts in the latter scenes that represent the end of the decade. We understand why Irving prefers not to note this as we look at the photo projections of them dressed to the nine’s decades earlier. Though we laugh, we get the undertones when Irving asks why Larry can’t use this photo where Jean is just stunning and Irving is certainly her inferior in the looks department.

The photos and videos blown up and projected on the set’s back wall become the backdrop upon which the actors acutely portray these individuals so that we become acquainted with them as archetypes with whom we identify. Thanks to 59 Productions these are integral to the themes in the vignettes. And they make all the more vital and poignant the last lines of the play when we discover that Jean dies after they move to Palm Springs (something which Larry disapproved of more for himself than for his parents). And as Burstein’s Larry proclaims his father’s illness and his death, his last lines fade and a visual of the photographer Larry Sultan is projected. Larry and Irving died in the same year, 2009. One cannot help but be stirred looking at his beautiful picture as a crystallization of his ancestry and his honest tribute to his parents in text and photos and this play’s messages of love, family, “seizing the day” and “memento mori.”

Kudos to Jennifer Moeller (costume design) Jennifer Tipton (lighting design) Scott Lehrer and Peter John Still (sound design) and Tommy Kurzman (wig/hair and makeup design) and of course 59 Productions projection design for bringing to life with the actors’ prodigious efforts the director’s stunning vision..

Pictures From Home is a must-see for the performances, the themes, the direction, the complexity and nuance of the play itself. For tickets go to their website, https://picturesfromhomebroadway.com/

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

‘Intimate Apparel’ a New Opera, a Must-See at Lincoln Center Theater

Posted by caroleditosti

Lynn Nottage’s superb play Intimate Apparel won an Outer Critic’s Circle Award and New York Drama Critic’s Circle Award. It is a play about women circa the turn of the century, the parallels and disparities between race and class, black and white, wealthy and struggling. For the women, gender is the equalizer. This is especially so in Intimate Apparel the opera presented at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse until the 6th of March. As such this new work is dramatic, taut with undercurrents and themes propelled by Ricky Ian Gordon’s thrilling music and Nottage’s memorable libretto.

Nottage has streamlined her poetic work for Gordon whose music is stylized and hybrid, born out of Nottage’s characterizations to elucidate profound themes that resonate with the audience. Gordon and Nottage are a pairing made in heaven. The production, well thought out by director Bartlett Sher, is all that one might want in raw emotional grace, generated by Gordon’s luscious notes, conveyed by the beautiful, heartfelt voices of the leads and their chorus counterparts.

Sher’s staging features stylized economy and nuance, unencumbered by the extraneous to allow the themes and characterizations to strike with impact. The action takes place on Michael Yeargan’s revolving turntable stage as the world of these characters is circular. The props are efficiently rolled out. Highly specific to the story, they are inconsequential once their purpose has been fulfilled and they dissipate into memory, supplanted by another scene and other props. All reflects an impermanence and hint of symbolic meaning, the tip of the iceberg, like the photographs that appear at the end of each act that Nottage has moved from play to libretto. It is a smashing touch that adheres thematically when we see the floor to ceiling size pictures of the characters “unidentified,” though we have been privileged to have their lives unfold during the opera.

The characters, like us, are subject to their time and place and though they appear to move forward, they remain static, even going backward psychically (George Armstrong, Mayme, Mrs. Van Buran). Forward movement and progress is an illusion, especially for unmarried Negro seamstress, Esther (Kearstin Piper Brown). Nottage effectively draws her arc of development so that Esther is fated to return back to the same setting by the opera’s conclusion. It is in the boarding house of Mrs. Dickson (the superb Adrienne Danrich), when we first meet Brown’s unhappy Esther.

Nottage’s message is clear. Throughout Esther has been through an emotional cataclysm as many black women experienced at the time, marching without notice through history, bearing up against what the society dealt out. Yet, Esther comes through it. And though she ends up in the same place, she is strengthened, stoic, heroic, independent and dignified. Indeed, Esther lands on her feet, perhaps wearily, but she will continue. And it is this delineation of character that Nottage, Sher and Gordon understand in their bones, so that they translate her characterization magnificently into this heartfelt operatic presentation.

From the outset we recognize that Esther is unlike the other women in the boarding house where Corinna Mae’s wedding ceremony is being held. Esther supports herself and is alone, working continually to make her way, not distracted by friends or entertainments which she cannot afford. Thus, she isn’t tempted by the ragtime music that we hear “downstairs.” Throughout, she avoids Mrs. Dickson’s encouragement to meet with one man or another to settle down. Ironically, when she should take Mrs. Dickson’s advice, she doesn’t and pays the price for it.

As the opera opens Esther, annoyed and jealous at Corinna Mae’s marriage, admits to Mrs. Dickson she doesn’t feel she will be loved. Nottage’s libretto melds with Gordon’s party ragtime, as it flows into refrains, “I hate her laughter,” “I hate her happiness.” The libretto throughout is lyrical and grounded in emotional realism as Gordon’s recitative rises to meet the character’s desires and feelings. In this case, Esther yearns to be loved, but feels it is hopeless. But by the end of the scene, she receives a letter given to her from Mrs. Dickson. Perhaps, it will satisfy her longings. Brown’s voice and acting targets our emotions and draws us in to her hopes and concerns. She is wonderful.

The letter is from laborer George Armstrong (Jorell Williams on Sunday matinee when I saw it). From Barbados, working on the Panama Canal, George Armstrong is an acquaintance friend of someone she knows in her church. The letter becomes the driving force of the action in the opera as it is in Nottage’s titular play. Esther, who can’t read or write, solicits help from two of her clients who are literate. Both women, opposite sides of the same coin, make their living from men, unlike Esther. One is the white elite society woman, the wealthy Mrs. Van Buren (the fine Naomi Louisa O’Connell), whose husband supports her in style but who is disassociated from his life emotionally, psychically and physically. The other is Mayme (Tesia Kwarteng on Sunday matinee when I saw it), who sells her sexual favors and takes beatings from the men who pay her for her services, one of which is to abuse her. She, too, is removed from the men to whom she plies her trade in an incredible irony of intimacy.

As Esther sews the same beautifully made “intimate apparel” (calling forth what true intimacy might mean), so they can attract the males in their lives, both help her write the letters to George. Mrs. Van Buren supplies the technical expertise and Mayme supplies the romantic allurements and sugar. During the process Esther becomes their confidante and she becomes theirs. The relationships are enlightening and Nottage reveals the parallels among the women, who the men dominate and abuse emotionally, psychically and physically. Thus, there is no difference between Mrs. Van Buren or Mayme; though the disparities in economic and financial well-being and respect based on race and class are galaxies apart. The women’s scenes with Brown’s Esther and her clients portrayed by O’Connell and Kwarteng are well drawn and ironic, as they move the action forward.

Both “kept women” ply their sexual trade, and though there is the appearance of a vast difference, certainly prompted by women elitists, the women, who are representative of their classes are oppressed. Esther is less so because of her independence and dominant attitude not to embrace the values that keep women enslaved to men. However, Esther, too falls from that grace, and the opera is an affirmation that she must learn that what she has achieved is indomitable and superior to the other women at this time and place.

Ironically, Mrs. Van Buren asks Esther if she is a suffragette when she makes a remark that sounds like women’s empowerment. Esther, in spite of herself, encourages Mrs. Van Buren not to “let him do you that way.” For her part Mrs. Van Buren is stuck in the psyche of her “feminine” class stature. She must fit into the stereotypical cut-outs of elite women. She will be the last to realize the vitality of empowering gender identity and women’s rights. She is her husband’s chattel, dependent on him for support, choosing not to work or seek out a skill which is beneath her. Mayme, like Mrs. Van Buren, is oppressed by the men who pay her. Without a skill to support themselves, Mayme and Mrs. Van Buren are sisters born of the same mother of servitude, soul demeaned without independence.

Esther’s scenes with O’Connell’s Mrs. Van Buren and Kwarteng’s Mayme resonate powerfully. During these scenes especially we understand how the women lure Brown’s Esther (though she has asked for it). Stirred by Mrs. Dickson’s values of a woman’s world defined by a man who keeps her, she and Mayme encourage Esther to “fall in love” with George who is a figment of all their imaginations. This is rendered beautifully in the aria when Mayme and Esther sing about the discovered George who has been with both women. It is then Esther tells Mayme not to let him in the door (symbolizing the door of her heart). “Let him go. He’s an unanswered letter, a feather on the wind, you’ll be chasing him forever.” Brown’s emotional highs and lows tear at our hearts; Nottage’s libretto is poetically striking.

To Mrs. Van Buren Esther represents a freedom and openness she craves in her life. However, the three women sing “I fear I love someone,” a melodic song signifying the love is a symbolic, forbidden creation of their hears and minds. For Esther her forbidden love is Mr. Marks (the wonderfully authentic Arnold Livingston Geis). Marks is the orthodox fabric seller on Orchard Street with whom Brown’s Esther forms a spiritual attachment. For Mrs. Van Buren it is the allure of the forbidden (spoiler alert), Esther who makes her feel accepted and loved for herself. For Mayme it is George’s razzle dazzle manly male, who flashes his money (actually Esther’s money), so they can enjoy themselves. His manipulations have convinced Mayme that he is her “Songbird,” though he is married to Esther.

The love Esther, Mrs. Van Buren and Mayme sing of cannot be purchased; it remains outside of their reach. They are confined by folkways and unable to cross those lines in 1905. Love remains that which is a financial and business arrangement pragmatically as Mrs. Dickson suggests happened in her life. Or it is a fantasy that little girls are taught to dream of to anticipate marriage, which in reality is a bondage, they cannot easily escape after marriage.

Esther’s relationship with Mr. Marks is vibrantly drawn by Nottage’s libretto and sonorously, poignantly brought to life by Brown and Geis. Sensitively, the actors delineate their mystical union, which is limited by folkways. The fabrics Mr. Marks saves for her carry great meaning and sensuality. Their closeness is beyond professional as their glances and smiles reveal they yearn for each other. Just a casual touch is significant. After Esther is married she tells Mr. Marks she can’t see him anymore and her answer when he asks, “Why not?” carries the weight of the world, “I think you know why.”

However, their last meeting occurs when Brown’s Esther gives Geis’ Mr. Marks the smoking jacket that she gave to George, that George gave to Mayme and that Esther took back from Mayme. It is then that we know the value of “intimate apparel,” and how the symbol has final closure. Intimacy isn’t necessarily in a physical acquaintance, it is soulful and spiritual. Esther, who made the jacket on his recommendation tells him, “It was made for you.” His wearing it will have symbolic meaning for him and for her of a love that was never consummated, but a transcendent love that prospers, regardless of nullifying strictures, prejudices and folkways. What a poignant, memorable satisfying moment, superlatively performed by Brown and Geis. Just smashing!

The finely wrought and beautifully designed costumes by Catherine Zuber are characters unto themselves, measuring out the symbolism, conflicts and themes of class, gender and relationships. From lighting (Jennifer Tipton), to sound (Marc Salzberg), to projections (59 Productions), the technical effects are right on, enhancing this exceptional production. Placing the pianos on platforms above the playing area is enlightened, as the music and musicians are integral to the action, driving it, supporting it. Their visibility is dynamic. Kudos to Steven Osgood’s music direction and Dianne McIntyre’s choreography.

Intimate Apparel closes on March 6th unless it is extended which it should be. Though the audience was packed, more individuals need to see this production which hits it out of the ballpark. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.lct.org/shows/intimate-apparel/

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp