Blog Archives

‘Endgame’ by Samuel Beckett at Irish Repertory Theatre is Amazing

Nobel prize winner Samuel Beckett suffered years of rejection until his wife managed to sell his work which gradually put him on the map. Now we question how this rejection was possible because his work is timeless and exemplifies his genius. His particular greatness lies in his creation of spare, staccato, memorable dialogue, enigmatic characters and static situations as metaphors of human existence and its banal, opaque meaninglessness. How could anyone miss Beckett’s exceptionalism? In Endgame Beckett believed he was at his best. Gloriously, the Irish Repertory Theatre is presenting this work and the production directed by Ciarán O’Reilly reflects the accuracy of Beckett’s opinion.

Starring the irrepressible Bill Irwin as Clov and stolid John Douglas Thompson as Hamm, the production is perfection in its minimalism and ironies. It appropriately allows the audience to focus on the principal characters and their dire circumstances as they confront the end of the world, the end of their relationships with each other, their personal closure, and the abject null of lives lived in their last days, without joy, empathy or compassion. Interestingly, the play’s conclusion appears to happen in real time. When the final words are proclaimed, Hamm’s story is told and the lights go out to audience applause. All that has been said and has needed to be expressed is said and done. And there is the precise end of it, as the audience is left to wonder and take nothing for granted about their own existential happenstance and what they have just witnessed in this shared humanity that plays out in a tragicomic unspooling.

Apart from their physical conditions of wrack and ruin, the characters are essentially ciphers. Hamm is blind and wheelchair bound, dependent on Clov, his handicapped, scattered servant, who begrudgingly comes to his every “whistle” and obeys Hamm’s commands. Clearly, their symbiotic relationship is one based on mutual abuse and co-dependence, as there is no love lost between them, though they’ve known each other since Clov was a child. Throughout the play, Clov limps with a barely controllable gait and awkward mobility to Hamm’s imperious orders. Toward the end of their repetitious tedium together, Clov even remarks he doesn’t understand why he continues to obey the cantankerous, unloving, pain-filled, acerbic older man.

In addition to Clov and Hamm are Hamm’s elderly parents who abide in the same large, spare room. They, also have lost their mobility and live without their legs in garbage cans filled at the bottom, first with sawdust, then more recently with sand. There are lids on the garbage cans, and the parents pop up for a conversation, until Hamm is tired of them and tells Clov to shut them up and close them out. Ironically, in the brief time we come to know father Nagg (Joe Grifasi) and mother Nell (Patrice Johnson Chevannes), we appreciate their relationship and the affection between them. Beckett reveals their togetherness as they recall the good times they had with each other, even making light of the accident when they both lost their legs. They put up with their son’s abusive, cruel nature and forbear under his insults (he refers to Nagg as a “fornicator”). As a result we perceive them as empathetic characters, while Hamm appears all the more obnoxious and querulous.

These four hapless individuals are perhaps the last human beings in the world. Hamm refers to the external environment outside the ramshackle building where they reside to be filled with death. The assumption is that the apocalypse has happened and there’s nothing left but a wasteland. The only objects that appear to make sense are inside their meager abode. These include Hamm’s piercing whistle, a few biscuits (in the play they look like dog biscuits) and Clov’s paraphernalia which include a spyglass and a ladder, an alarm clock and a few other items. There is also Hamm’s pet dog which is a stuffed animal, which may or may not give him comfort amidst his whining about “it’s” being enough, asking for his pain killer and his attempts to finish the story that he’s trying to tell, which symbolizes his and Clov’s lives.

The laughable irony is that the end of days are inhabited by these infirm individuals led by a powerless, despotic miscreant who presides over the others like a king, though he is powerless, halt, lame and blind (the Biblical reference is intimated). Instead of his physical helplessness guiding him into humility, the opposite is apparent. He is full of himself in his miserable state, which he appears to masochistically enjoy. (“Can there be misery loftier than mine? No doubt.”)

Hamm and Clov are contrapuntal. They are unique personalities and they contradict each other but come to the same conclusions. Their state of existence must end and it has gone on long enough without meaning. As they speak to each other in short bursts of, oppositional banter, the overall effect is humorous, like a bad joke or punchline. However, their thrust and parry about “nothing” has philosophical power in their sporadic digressions about life, time and existence. Their interactions often end with a surprising, pithy statement from either of them and the overall effect is also like a poetic riff. For example Hamm says, “It’s a day like any other.” Clov counters, “As long as it lasts. All life long the same inanities.” In their counterpoint, there is the great observational moment about the redundant, vapid routines of living.

Considering that apart from a few moments when Clov looks out the window, and Hamm directs him to “drive” his wheelchair around in a circle, Clov kills a flea by throwing powder down his pants and Hamm uses a staff-like implement to try to move himself which he can’t, little happens. From beginning to ending they know the situation is absurd because their end is inevitable and irrevocable. And because they are helpless against time and existence itself, they can do nothing except what they do and say which is both funny and tragic.

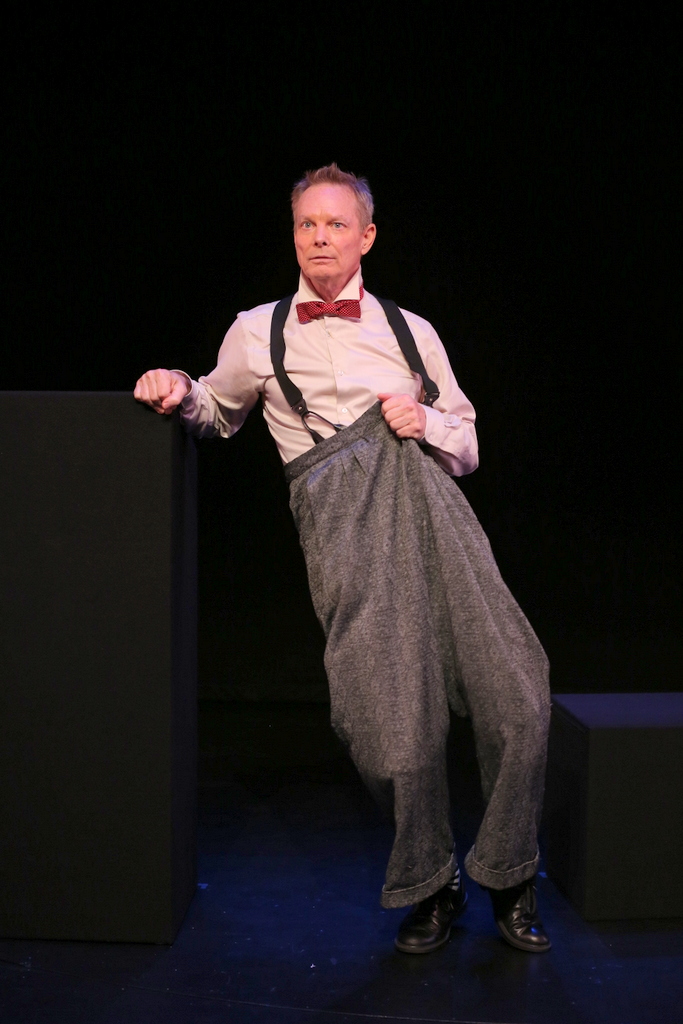

Bill Irwin’s Clov is a mastery of awkward physicality precisely effected. He is imminently watchable and uncharacteristic in his movements which are surprising and antic. In his stasis, John Douglas Thompson is his frustrated counterpart. Their banter is humorous and paced with authenticity bringing on the chortles and laughter because their characters are so passive and truthful about their condition. No one is raging against the storm which has already happened. They are waiting the interminable wait for “the end.”

O’Reilly’s direction and staging align with Beckett’s intent and we find ourselves mesmerized and waiting for the shoe to drop,, which only does in the little details and actions. One example of this occurs when Clov sets up the ladder and climbs it, anchoring his leg so he might safely look out the window on the “grey.” Another example occurs when Clov gets rid of the flea with the white powder which he roughly sprinkles down his baggy pants. A third action occurs when Clov brings out an alarm clock and hangs it on the wall. Each of these “events” and others (Hamm’s petting his stuffed dog, Hamm’s attempting to move himself with the gaff) create a kind of suspense that ends in nothingness. This is one of the themes of Endgame; ultimately, our actions result in little that impacts or changes existence. However, they do help to pass the time and “entertain” us until “the end,” which is uncertain.

Charlie Corcoran’s scenic design, Orla Long’s costume design, Michael Gottlieb’s lighting design, M. Florian Staab’s original music and sound design convey the austere setting of a ramshackle room in a house beset by a post-apocalyptic, end times scenario. That the title references a game of chess where there are no winners and one of the players (Clov) threatens to leave numerous times but remains at “the end” is to Beckett’s purpose that all inevitably wanders into empty inaction which has little substance or meaning. Thus, we are left seeing characters confronting what they cannot, as we witness our own inability to reckon that there is an “end” to all of “this.” And as Nell states, nothing is funnier than unhappiness. So as we watch the characters struggle with their fateful endings, we laugh because life is nonsensical. And we are sad for the tragedy that reflects our own humanity.

This is an amazing production with flawless performances that you don’t want to miss. For tickets and times go to their website https://irishrep.org/show/2022-2023-season/endgame-2/

Bill Irwin in ‘On Beckett’ at the Irish Repertory Theatre, Off Broadway Review

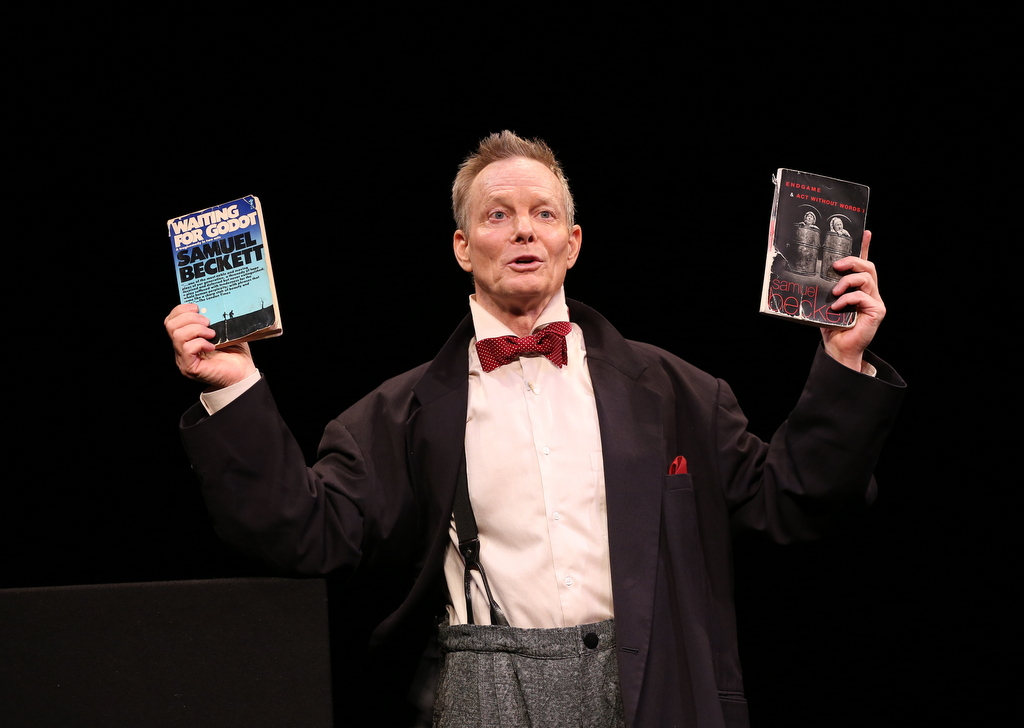

Bill Irwin, ‘On Beckett: Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett,’ Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Has there ever been a more elegant, erudite and riotously funny clown prince of theater than Bill Irwin? Not only has the Tony Award winner mastered the innards of pacing, rhythm, mime, body visualizations and timing of the comedic. Irwin writes, directs, acts. What does he not do well theatrically and dramatically? In what he attempts, Irwin delights. In his On Beckett at the Irish Repertory Theatre, Irwin examines the opaque and timeless works of Nobel Laureate Samuel Beckett. What an exquisite evening Irwin conceives, directs and performs.

On Beckett: Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett introduces us to lesser-known works, and he revisits the often performed Waiting For Godot with the assistance of Finn O’Sullivan as the boy. Irwin appeared in the 2009 production of Godot and received a Drama Desk Award nomination.

As he presents Beckett’s less familiar writings, he acknowledges the importance of the playwright’s Irish voice, identity, and heritage. Notably, Irwin showcases passages from Beckett’s elusive Texts For Nothing (13 short prose pieces), pointing out that Beckett wrote the arcane prose pieces in French, then translated them into English, his native tongue that Irwin identifies as the “familiar familial voice.” As an Irishman writing in French, Beckett maintained his uniquely Irish ethos but received widespread acceptance in France initially. The irony astounds as it is “the product of a complex translation exercise.”

The prose pieces Irwin performs, #1, #9, and #11, are masterworks about being, absence, presence, and vacancy, all interior dialogues and questions. They reveal the common man/woman’s struggle with self in a massive inner argument that represents individual consciousness. And they reveal the human condition of impoverishment, failure, exile, loss. In the passages Irwin selects, Beckett wrangles the concept of consciousness. Indeed, these excerpts reveal the act of viewing oneself in despair, in parallel with the self experiencing despair.

(L to R): Finn O’Sullivan, Bill Irwin in ‘On Beckett: Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett,’ Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg).

Thus, from both perspectives Beckett suggests questions about existence, survival, struggle, and purpose. The will “not to go on” while “going on” remains paramount in Beckett’s darkest, bleakest comedy. These elements Irwin melds with the cliché of the Comic Irishman “who has waiting to do” and “struggles with the notion of ease, and his placement in the larger scheme of things.”

In his comments before and after excerpts from Beckett’s novels The Unnamable and Watt, Irwin questions: “Is he making fun of the way consciousness works?” Or “is he offering a portrait of consciousness?” As we appreciate this rare experience that Irwin delivers with aplomb, we understand Beckett’s extraordinary contributions. Not only did he assist in the transformation of English modernist literature, he was credited as integral to the Theatre of the Absurd along with Eugene Ionesco and Harold Pinter. Whether he would have appreciated the latter is debatable.

Notably, through his discussion we get to realize another facet of the diamond that is Bill Irwin’s artistry. In acting Beckett, he questions and appropriates the language and suggested meaning for himself. All of this pertains to and infuses his own relationship to art, acting, clowning, and theatrical expression. Shepherding us through Beckett’s language, Irwin ignites our passion. And he makes Beckett and perhaps ourselves more comprehensible in all the abstruse glory of the incomprehensible tragicomedy of life. Indeed, in his “Introduction” Irwin discusses how Beckett’s unforgettable words have gone viral within him, have haunted him. Certainly, the language resounds in his “head,” “heart,” “brain,” “mind,” “psyche,” “body.” This interesting admission yields that Beckett has been integral to Irwin’s evolution as a man and an actor, as a clown and an artist.

Bill Irwin in ‘On Beckett, Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett,” conceived and performed by Bill Irwin at the Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Irwin’s comments sparkle with witty self-effacement. For example in outlining the evening, Irwin references the show lasting 86 minutes or so and quips, “I say this by way of reassurance.” Indeed, Beckett is not easy. But through Irwin’s humor we gradually become intrigued about his novel approach toward his subject and his singular recognition of Beckett’s language.

Irwin gets inside Beckett as an actor, and also explores his work from the perspective of clown theatrics. The great clown traditions, Irwin tells us, are “the lens through which he views everything.” And indeed, he applies this lens to exploring the extent to which he views Beckett as clown territory. Irwin’s hapless Clown characters and the techniques he employs to achieve this archetype everyperson provide the uplift to laugh at our shared humanity.

Revisiting Beckett from this unusual angle, Irwin’s organic acting and portrayal of Beckett’s clown characters enlightens. Cleverly, his performance and astute commentary about acting and language shine a beacon into Beckett’s mysterious obscure.

Kudos also go to Charlie Corcoran (scene design), Martha Hally (costume consultant), Michael Gottlieb (lighting design), and M. Florian Staab (sound design). Don’t miss seeing this wonderful presentation if you can get tickets. It closes on 4 November. Click here for the Irish Repertory Theatre website for times and tickets.