Blog Archives

‘Hell’s Kitchen’ Blasts Onto Broadway and Electrifies With New York’s Resounding Energy

Hell’s Kitchen, premiering on Broadway in its transfer from the Public Theater is nothing short of gorgeous perfection. Though the creative team rendered a phenomenal production in the fall of 2023 at the Public’s Newman Theater, the 299 seat venue and smaller stage offered a constricted space. The Shubert Theatre Broadway is the proper venue for this update, expanding the bravura performances and allowing for the outsized dance numbers and abundance of talent that is free to explode with musical glory. This production is totally “on fire” and more than “ready” for Broadway in a masterful presentation of Alicia Keys’ music in a coming-of-age story that is inspired by her own life!

With its apparently seamless transfer, Hell’s Kitchen, with book by Kristoffer Diaz, Alicia Keys’ glorious lyrics and music, Adam Blackstone’s music supervision, Camille A. Brown’s dynamic choreography, Michael Greif’s thoughtful direction and Alicia Keys and Adam Blackstone’s arrangements of key songs from her repertoire (and a few new ones), what’s not to adore?

Integrating Keys’ playlist with an organic story rooted to a New York setting during a period of a few months, Greif, Keys and Diaz’s choices stir up the magic that makes this production uncharacteristic and unique, far from the typical obtuse branding of a “jukebox” musical, which it isn’t. The overriding conflict in Hell’s Kitchen is between mother and daughter in their story of reconciliation, which on another level writes a love letter to New York’s loudness, brashness, street people, and atmospheric social artistry in the 1990s.

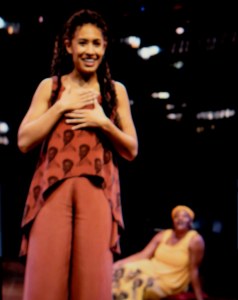

Even if you are not an Alicia Keys’ fan, you will be enthralled with the performance of the sterling, exceptional voice and presence of Maleah Joi Moon, who is the frustrated Ali, who casts herself as the princess her mother (Shoshana Bean), cages in their apartment. Ali fights for her “freedom” against her narrow vision of her “monster” mom who she believes is a restrictive, paranoid, hypocrite who doesn’t know what life is about. Meanwhile, underneath, she is crying inside, but doesn’t realize how and why.

Using flashbacks from the present with events highlighting all the characters that mattered in her life at the time, Ali tells her story of a special summer, not as we are initially led to believe, because she is with a man. Rather it is a reflection on her past from which she gains wisdom and understanding, through love, sorrow, heartbreak and renewal. The backstory of Ali’s life at Manhattan Plaza, a subsidized residency for artists, is revealed in various songs: “The Gospel,” “The River,” “Seventeen,” and others. Through her storytelling, she reveals her understanding of how pivotal these events are in her relationship with her mother and father, and her relationship with herself as an artist.

Ironically, Jersey (the non pareil Shoshana Bean), knows all too well how one is caught up in the distractions of the opposite sex (“Seventeen”). She coupled with Davis (the soulful Brandon Victor Dixon), when both were not ready to be Ali’s parents. While Davis took off to pursue his career, Jersey gave up hers to raise Ali, work two jobs, live in subsidized housing for artists at Manhattan Plaza, and attempt to corral Davis whenever he was in town to be a father to Ali. Though Ali knows the facts about her parents, she doesn’t understand the profound nature of their relationship as it relates to her. She resents Jersey and Davis and tries to suppress underlying anger about feeling unloved, unwanted and tyrannized. The rage spills out continually against Jersey who must take the brunt of it as a single parent.

Ali seeks her identity and purpose apart from the family situation and her father’s “abandonment” that she rages against. Spurred on by her friends she throws herself herself at Knuck (Chris Lee). The twenty something is one of a three-person bucket drumming crew providing excitement and sexy currents busking in the courtyard of Ali’s residence. Ali’s attraction to him is so palpable, Jersey warns the doorman and her police friends to “watch out” for her daughter’s wiles with the “bucket drummer,” which miffs Ali. When tensions increase with her mother, Ali seeks comfort from Miss Liza Jane’s (the incredible Kecia Lewis), classical piano playing in the Ellington Room of Manhattan Plaza, which so inspires her, she realizes she’s found a part of herself, (“Kaleidoscope”).

There is an underlying irony that Diaz’s book suggests about Ali’s selection of Knuck. Of all the guys at her disposal in New York City, the ultimate attraction falls under her mother and her gossipy doorman’s and neighbors’ noses. Of course her mother is provoked and has a friend cop disperse the drummers. The drummers think they are unwanted because Ali’s mom is white and a racist. Though they are not arrested, the event is frightening. Importantly, it reveals Ali is selfish and willful. Her underlying problems with her family will leech out to impact her relationships unless she checks herself and tries to resolve them, but at this juncture, she doesn’t. Instead, she searches out Knuck who tries to tell her his experiences as a Black man fighting an identity he is branded with, in an attempt to get her to understand that the situation with her white mom’s reaction is dangerous (“Gramercy Park”).

In an attempt to reach out to her daughter, Jersey discusses why she is so “paranoid,” and we get to meet the sexy Davis (“Not Even the King”) when Brandon Victor Dixon smoothly croons his heart out. Bean’s Jersey joins him in “Teenage Love Affair,” and we understand how both allowed the sizzling attraction between them to overthrow rationality, precisely what Jersey fears will happen to Ali. After her discussion with Ali, it seems that mother and daughter have reached an agreement and understanding. However, Ali pushes that understanding aside and willfully seeks out Knuck.

With almost unconscious rebellion, without regard for Knuck (she lies about her age), she pursues an intimate relationship with him (“Un-thinkable [I ‘m Ready]). Indeed, with her provocative behavior, encouraged by her friends in the astounding “Girl on Fire,” she boldly brings Knuck to her apartment, flaunting her faux adulthood on Jersey and disrespecting their home. is it any surprise Jersey finds them in a state of undress? The white mother who has branded Knuck throws him out; and that is when he is told Ali is underage. He runs for his life.

When Ali runs after him, there is confusion and chaos downstairs where his friends have been drumming. Ali tries to apologize to Knuck in front of the crowd when Jersey stops her, tells her to go upstairs and slaps her when she ignores her. Jersey’s action serves as a trigger, the doorman catches Knuck, and cops arrive with flashing red lights to arrest the drummers.

In a typical aftermath, we don’t know if the drummers who have done nothing are OK or not. A hysterical Ali is helped by Miss Liza Jane who finally gets through to Ali (“Perfect Way to Die”), helped by the Peter Nigrini’s projection design which include black and white photos of sons and daughters who have been the victims of police brutality, otherwise known in the South as lynchings. In the interlude Miss Liza Jane tries to encourage Ali, inform her about the racial history of the US and quietly suggest that she can’t afford to be reckless in a racist culture. Miss Liza Jane affirms that Ali must take her anger and pain and use it for an artistic purpose. This is another major theme of Hell’s Kitchen, a theme which Alicia Keys and her friends in the music industry realize every day of their lives.

Interestingly, Hell’s Kitchen doesn’t beat the audience over the head with police brutality; no one is injured, but Miss Liza Jane, who shares her historical, personal experiences sings/speaks to Ali like an adult who can understand. Wisely, Keys and Diaz reveal sub rosa the institutional racism in the culture as it is suggested in “You Don’t Know My Name.” In that song, they emphasize the harm in stereotyping, branding and dismissing the humanity of Knuck as “invisible.” Indeed, Jersey falls into the trap out of fear, though she is not a racist and has a mixed race daughter. Nevertheless, this profound concept is revealed; and as open minded as Jersey is, she is unfair to Knuck. Her daughter is to blame for lying to him.. In how many situations like this have Black men been killed? Knuck and his friends, thus far, have been fortunate.

Moon’s Ali is a combination of innocent and alluring, a convincing “wild child” who wants to attract Knuck, the forbidden prize she can toy with, (repeating the same situation her mother was in), to provoke Jersey for love, or perhaps to drive at a deeper understanding between them. Her obtuseness in endangering Knuck and the others, until the amazing Kecia Lewis’ Miss Liza Jane, and Brandon Victor Dixon’s superb Davis counsel her, is key to her evolution. Importantly, it is a vital mentoring theme for teenagers.

In Act II, when Ali suffers a touching loss that she can’t overcome, but can only move forward through, Moon is just terrific in expressing her hurt and sorrow with grace. Her performance is a smashing powerhouse. Likewise Shoshana Bean as Jersey, in her presence, her fear, anger, panic and emotionalism, rocks the role out of the ballpark.

The two actors create a felt relationship that is authentic and heartfelt. They effect a mother daughter bond that satisfies all the digressions from rebellion, to incriminations to regrets, to sorrows, to reconciliation and a forever, spiritual love which Act II’s songs encompass, especially “If I ain’t Got You,” Hallelujah/Like Water,” “No One.” And of course Hell’s Kitchen wouldn’t be “Hell’s Kitchen” without “Empire State of Mind” in which all the creative team, the swings, Chloe Davis (dance captain), and others pull out the stops and dance and sing passionately as Peter Nigrini’s marvelous projections of New York City’s aerial views at night, form the moving backdrop.

Kecia Lewis as Miss Liza Jane, Chris Lee’s Knuck and the smooth, silky voiced Brandon Victor Dixon are the counterparts of Maleah Joi Moon and Shoshana Bean. The bucket drummers, and Ali’s girls have exceptional voices and presence. There is no spoiler; I’ve intentionally left out a discussion of how the resolution and renewal occurs and when it occurs in Act II.

You really shouldn’t miss Hell’s Kitchen, especially if you are a New Yorker.

Finally, Michael Greif’s vision, his integration of Robert Brill’s fabulous scaffolding scenic design with the rectangular construction grids stylizing the New York City buildings with neon lights, is perfect. Situating the musicians above on the scaffolding so the music rings out the harmonies of Adam Blackstone’s and Alicia Key’s arrangements, in fact all of it, including Natasha Katx’ multi-colored lighting and spots are breathtaking. Importantly, Gareth Owen’s sound design is balanced and painstakingly effected, so I heard each word. On many musicals, the sound design is problematic and slips. Owen’s was right on. Dede Ayite’s costume design and Michael Clifton were period appropriate. The Hilfiger and Gap brands, cargo pants, mid-drift tops, low slung pants with jazzy underwear, and sparkles and shimmering outfits when most needed (especially the last song), were fun and New York identifiable.

All the creative elements aligned with Greif’s vision of a Hell’s Kitchen which is undergoing transformation and hope, despite unresolved institutional racism and discrimination.

As with the Public’s production I was thrilled by Camille A. Brown’s choreography and the dancers’ amazing passion and athleticism incorporating a variety of hip hop dances from the period and then evolving into something totally different. Unusually, there is movement during times when least expected, but all correlated with the emotion and feeling of the characters making the dancers’ moves expressive and coherent.

I’ve said enough. Get your tickets. After the Drama Desks and Tony’s the prices will be higher and you won’t be able to get a more affordable ticket. Now is the time.

Hell’s Kitchen in its Broadway premiere runs two hours thirty-five minutes at the Shubert Theatre, 235 West 44th Street between Broadway and 8th Avenue. https://www.hellskitchen.com/

‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf’ Amazing!

When you have contemplated suicide, the rainbow with all its Biblical and mythological significance is not enough. The pain is cyclical, repetitive and cataclysmic until you end it. However, in ntozake shange’s choreopoem, for the empowering community of black women shining through the clouds of history to speak an anointed truth that has been forged like gold over the centuries, the embodiment of the living rainbow of love is enough.

The revival, currently at the Booth Theatre is directed and choreographed by the anointed Tony award nominated Camille A. Brown (Choir Boys). Shange’s iconic tone poem was initially presented on Broadway in 1976 to great acclaim, transferring its success from the Public Theater. Brown’s re-imagining is a heightened elucidation, different from the 2019 production at the Public Theater which featured mirrors, a disco ball and other shimmering dance party effects.

Brown and her design team have removed elements of reflection in the 2019 production and worked toward an affirming strength in the divisions of light divided through a prism to become seven color bands whose hues are picked up in all the dramatic elements of theatrical spectacle engineered by the creative team. The team manifests the vibrant colors of creation and coordinates them with lighting design effects (jiyoun chang) and eye-popping emergent luminescence in a multitude of shapes projected on large panels on both sides of the stage (myung hee cho-scenic design, aaron rhyne-projection design).

To original music and Brown’s seminal choreography the team ingeniously relates Shange’s poetic story themes. Each monologue and bridge by the company reveal a prodigious conceptualization. As they relate theme to color, the actors’ dance and movement resonate the energy of the color they “wear” (sarafina bush-costume design), enhanced by the coordinated lighting and the projections as the music synthesizes all these elements with astonishing power and emotion.

The large panels on either side of the stage close in the central focus on the majesty of the bands of the rainbow embodied in the following marvelous and sterling actresses who sync exquisitely in choreographed unity. These include Amara Granderson-Lady in Orange, Tendayi Kuumba-Lady in Brown, Kenita R. Miller-Lady in Red, Okwui Okpokwasili & Alexis Sims-Lady in Green, Treshelle Edmond & Alexandria Wailes-Lady in Purple, Stacey Sargeant-Lady in Blue, D. Woods-Lady in Yellow.

As each of the Ladies announce their stories and receive encouragement from their fellow hues, an emotional progression and journey emerges from youth to motherhood to sisterhood, healing and self-love. The emotions from each of the stories move from revelation to relational love and devastation, to acceptance and self-affirmation, to empowerment, with the merging of all the colors to self love which of course is light. (The rainbow is refracted sunlight through moisture prisms after a rain.)

Some of the colors and stories resonate with great joy and the exuberance of youth: the story of graduation night, the beginning of adulthood and sex for the first time by Lady in Yellow (D. Woods). Others take on the hue of the experience described: abortion cycle #1 by the Lady in Blue (Stacey Sargeant), who trails with “& nobody came, cuz nobody knew, once i waz pregnant & shamed of myself.” In the bridges to the monologues the rainbow ladies add their encouragement and dance with superb breath control and conditioning.

I particularly enjoyed Tendayi Kuumba as the Lady in Brown who humorously expresses her inspired love for “Toussaint,” whose books she discovers by sneaking into the adult section of the library. As a first foray into the world of a love mentoring, and influence, she lifts up the Haitian freedom fighter and he becomes her lover (she is a precocious 8-years old), and confidante late at night as they conspire “to remove the white girls from my hopscotch games.” The resolution occurs when she meets a “real-live-boy” named Toussaint who is interested in her. When she considers the great distance she must travel to Haiti, she decides he’ll do fine.

In the brilliant “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff” the Lady in Green (Alexis Sims when I saw it), identifies how the soul can be stolen. The outrage and anger belies the humor underneath as the audience realizes the Lady in Green’s outcry hits home. How many have subdued their inner voice and being for the sake of pleasing another and then didn’t process the identity theft until too late? When emotion and feeling end up residing in the power and confidence of another because of bestowment is this not a form of theft? As one of the more powerful of Shonge’s poems anger is appropriate because the theft is subtle and secret and must be watched or one loses everything.

Perhaps the most telling and dramatic is The Lady in Red’s monologue “a nite with beau willie brown.” Presented by the pregnant Kenita R. Miller, we understand the raw horror of a man who has gone over the edge with PTSD and who brings down everyone else around him. With three children willie brown is emotional, irrational and sly. He desires control and power over the Lady in Red and has beat and manipulated her. However, she has had enough. Miller’s performance builds and intensifies as she compels us to feel the real plight of trying to save the lives of children from their abusive biological father who doesn’t take responsibility for raising him; they aren’t married. Delivered with incredible empathy, love and force, Miller’s performance is breathtaking. Clearly, deeply she reaches the soul level, indicating what it is like to confront one who has learned to kill and can’t turn it off. Just dynamite.

Camille A. Brown has infused an emotional reality in the presence of these ladies of color that is felt and is experienced. Not only has she discovered the way of story telling through the actors’ rich performances, she has threaded their beauty through movement and dance, steady drum beats and lyrical notes of powerful, velvet femininity.

This is emphasized throughout, but perhaps most in the “laying on of hands” in which all of the hues anoint each other and the Lady in Red expresses in the beginning of the segment that there was something missing. But by the end in the company of the rainbow women, she states, “i found god in myself & i loved her/i loved her fiercely.” Only then after the expurgation of all that is ill in the culture to receive and distinguish all that is loving and graceful, the Lady in Brown concludes, “this is for colored girls who have considered suicide/but are movin’ to the ends of their own rainbows.”

Cookie Jordan’s hair & wig design speaks out to individuality, empowerment and self-confidence. This especially resonates in a world where women’s rights and “colored” women’s rights have been dismissed by white men who intend to rule like demented, genocidal lords over us if we let them.

The original music, orchestration and arrangements by Martha Redbone and Aaron Whitby flow seamlessly in and out of the gorgeous mosaic of Brown’s dance and movement choreographed to perfection against Shange’s poems, backdropped by sustained flashes of scintillating color projections. Drum arrangements by Jaylen Petinaud provide the beating heart of Shange’s work, pulsating energy and life. The music and drums electrify the actors who in turn electrify the audience in felt, authentic moments. Tia Allen as music coordinator and Deah Love Harriot’s music direction provide further grist to this intense team work that brings such memorable force to Shange’s masterwork.

This must be seen by every woman as it is an incredible, uplifting production that explores the secrets in every woman’s heart, unexpressed, felt, experienced. The production’s currency aligns with the recent Supreme Court draft to turn down Roe, an abomination of desolation, un-Christian, indecent, genocidal. Juxtaposed against wickedness, Camille A. Brown’s production is an affirmation of hope and the glory of womens’ empowerment to throw off the darkness. Indeed, as Shange shows us the way; the rainbow in the full representation of a unity of all colors in self-love is the light.

For tickets and times, go to their website: https://forcoloredgirlsbway.com/

‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ by Ntozake Shange in revival at the Public Theater

The company of ‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ by Ntozake Shange, directed by Leah C. Gardiner, choreographed by Camille A. Brown (Joan Marcus)

You cannot watch for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf without your muscles vibrating in joy to the rhythms of the music of Ntozake Shange’s poetry. And when it is set to the dance with musicians pealing out the songs of multicultural generations with her choreopoem delivered enthusiastically in the personal languages of black women from various backgrounds using their unique words, gestures and dance movements, it is simply grand.

for colored girls... directed by Leah C. Gardner with choreography by Camille A. Brown is now in revival at the Public Theater. Originally, the work premiered on Broadway in 1976 and received a Tony nomination. Notably, it is the second play by a black woman to reach Broadway, preceded by Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun in 1959. Shange updated the original choreopoem in 2010. She included additional material, the poem “positive,” and added references to The Iraq War and PTSD.

‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ by Ntozake Shange, directed by Leah C. Gardiner, choreographed by Camille A. Brown (Joan Marcus)

This iteration in its maverick coolness is a celebration not only of black women. It is for women everywhere. The work recalls us to a time when women reveled in the identity and unity of being female. It was a time in the feminist wave when they rejoiced being in a community of sisters from around the nation and the world. It was a time to become visible, be heard, speak truth to power, overcome, conquer. Considering the crisis and chaos the current WH administration attempts to breed in our culture in concert with a senate majority leader supportive of the white patriarchy who revel in misogyny, embrace white nationalism and leverage religion as a political tool, it is time to revisit the themes and messages of for colored girls… and view them through the lens of womenhood, including those who are most in bondage, white women.

Shange’s choreopoem as in other productions includes music and dance with some poems sung. It is performed by seven women each sporting a dress of a different color which combine to make up colors of the rainbow. As an ironic note, remember that all colors combine to create the color white representing what is sanctified and holy, if you will. Indeed, this “is enuf.”

(L to R): Jayme Lawson and Adrienne C. Moore and the company of ‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ written by Ntozake Shange and directed by Leah C. Gardiner, with choreography by Camille A. Brown, running at The Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

The woman/actors depicted in Shange’s majestic choreopoem are as follows: brown (Celia Chevalier), yellow Adrienne C. Moore) blue (Sasha Allen) red Jayme Lawson) purple (Alexandria Wailes) orange (Danaya Esperanza) and green (Okwui Okpok Wasili). Together and individually, they dance to express their identities throughout the work and also listen and partake in the community by sharing their wisdom and experience. At the outset of the production, each moves to center stage where via monologue, they contribute their personal message of womanhood.

As the various women play “tag, you’re it,” the first to begin, the woman in brown, steps into herself and with her own dialect, rhythms, gestures and carriage tells a story from her youth about her love fantasy Touissant. She first read about Touissant in the “forbidden” adult section of the library. Touissant was the black general who fought for France and ended up starting his own revolution reinforcing the Haitian slaves who ignited an insurrection against their bondage. Touissant continued their work and inspired a revolution against oppression which ended in a free Haiti.

The woman in brown’s love is metaphoric and symbolic. Touissant represents freedom from enforced bondage. In seeking him as her fantasy lover, the woman embraces the freedom to be herself in a culture that attempts to nullify her voice and identity. When she shares that she meets up with a boy named Touissant Jones, she realizes that one is similar to the other in not “taking any guff” from white people. She decides in her quest for escape from white supremacy’s mores (she had planned to to go Haiti) she will continue with the real Touissant Jones and become the freedom that Touissant metaphorically represents. She will make her own place regardless of whether “they” recognize her or not, for she has empowered herself to know who she is.

The company of ‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ by Ntozake shange, directed by Leah C. Gardiner, choreographed by Camille A. Brown (Joan Marcus)

Each of the women relate their personal stories in choreopoems. Some are humorous. For example, the woman in yellow shares giving up her virginity in a buick on the night of her graduation. When queried about it by the woman in blue, she tells her, “It was wonderful!” Each of the women chime in about where they “lost it.” The effect is funny and the sharing brings the group together in community. Moving in a different direction, the woman in blue riffs on her experiences running off at sixteen to dance with Willie Colon in the Bronx where she feels sublime dancing the mambo, bomba and merengue all night. But when Colon doesn’t show, she goes to a bar where she learns the beauty and subtly of musicians playing the blues. Her time center stage ends with a song/poem to the power of music and life. Sasha Allen’s voice is incredible.

Shasha Allen (center) and the company of ‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ written by Ntozake Shange and directed by Leah C. Gardiner, with choreography by Camille A. Brown, running at The Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

The woman in red gives a lament about throwing herself into the pursuit of a lover then ending the affair, a place all the women have been as they “dance to keep from” cryin’ and dyin.'” Then there is a transition; the light signals the emotional shift which deepens into the harder subjects beginning with rape. But is it rape when you know your rapist who is a friend or close family member? Each of the women relate their wisdom and finish each other’s thoughts for all have experienced the “latent rapist’s bravado.” These are “men who know us…that we will submit and relinquish all rights in the presence of a man…especially if he has been considered a friend…”

This section is particularly powerful in light of the #metoo movement. The women in the beauty of Shange’s verse and the rhythms of their movements share how the “nature of rape has changed.” You “meet your rapist in coffeehouses sitting with friends.” We can “even have them over for dinner and get raped in our own houses by invitation, a friend.”

The company of ‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf,’ by Ntozake shange, directed by Leah C. Gardiner, choreographed by Camille A. Brown (Joan Marcus)

Sadly, these lines are even more salient today as we hear the statistics: one in three women are raped in their lifetimes and more than a few are raped more times by different men. One thinks of the power dynamic of the Harvey Weinsteins, the Matt Lauers, the Bill O’Reillys, the Roger Aileses, and all those invisible bosses or friends who laud their “latent rapist bravado” towering over subservient females while boasting about their conquests in gyms and lockers rooms, while showering together. Women reduced, vilified, hated, objectified, say little for fear of more abuse or loss of a job and career. Or they are PTSD frozen by the audacity that someone took what wasn’t theirs to take. The #metoo movement is a first step. When the “latent rapists” are in jail and the men and women they would trample over with their violence are in positions of power, this justice will indicate the culture is climbing to the mountaintop.

Celia Chevalier (foreground) in for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, written by Ntozake Shange and directed by Leah C. Gardiner, with choreography by Camille A. Brown, running at The Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

Whether latent or verbally harass raped or physically abused, rape is violence. There is nothing sexual about it. In the infantile man’s mind, his penis is a weapon to slay and conquer women. Nothing adult or masculine! A man’s sexuality and masculinity are expressed in tenderness, truth and soul giving as the various women point out in their comments about men and relationships. But who is mentoring these traits of grace? Certainly not the president, or Jeffrey Epstein or Bret Kavanaugh or the Republicans and others in positions of power in business, politics and elsewhere who have sexual abuse on their resumes, hidden by AMI’s “Catch and Kill” program. (Read Ronan Farrow’s titular book on this subject.)

From rape, the rainbow of women present choreopoems about abortion, domestic violence, abandonment, devastating relationships and seeking identity through sex and love. And in the sharing of their trials, hurts and losses, especially the loss of self-hood, there is a benefit. Healing comes with love and empowerment to resurrect a new self inspired by the community of women who understand and uplift.

One of the more powerful, humorous and profound presentations references how women give their self-hood and identity to men and or the culture/patriarchy. The audience responded with laughter at what the woman in green meant metaphorically and symbolically with the refrain, “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff…now why dont you put me back & let me hang out in my own self?” Okwui Okpokwasili as the woman in green is riotous in her portrayal and stance as a woman who has realized that she has been giving all of herself away to one or many who don’t really understand or want her being.

“i want my own things/ how i lived them/ & give me my memories/how I waz when I waz there/ you can’t have ’em or do nothin’ wit em/stealin’ my shit from me/dont make it yrs/makes it stolen”

Okwui Okpokwasili (foreground) in for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, written by Ntozake Shange and directed by Leah C. Gardiner, with choreography by Camille A. Brown, running at The Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

Okpokwasili’s presentation resonated deeply not only with women but with men. Stealing is an analogy with the robbery of self and what one deems most valuable. In this instance, it also includes physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well-being that has been robbed by the culture and those brainwashed into theft. Just Wow!

The most poignant choreopoem concerns soul sickness and fear in men that converts to abuse and torment. The woman in red shares the dramatic events that encompass her children’s deaths at the hands of a former partner. The pain and torment from these experiences are related to the community of women who give a laying on of hands to bring on healing. And by the end of this section and the conclusion of the production, each of the women separately then in unity chant as a chorus whose vibrations go out into the audience, “I found god in myself & I loved her/ I loved her fiercely.” At this point the women though they may have considered suicide because of what they have experienced, in the companionship of sistahs have brought themselves and each other to the end of their own rainbows, “fiercely.”

This production is momentous. Shange’s poetry shimmers on the page. The creative team makes the director’s vision equally shine with brilliance. Kudos to Myung Hee Cho (scenic design) Toni-Leslie James (costume design) Jiiyoun Chang (lighting design) Megumi Katayama (sound design) Martha Redbone (original music) Deah Love Harriott (music director) Kristy Norter (music coordinator) Onudeah Nicolarakis (director of American Sign Language).

A caveat, however, is that some of the lyricism and the poetic language is lost in the exuberance of the performers’ actions, some more so than others. Specifically, the words, the expressions in all their glory are not always clear. Sometimes, these were garbled or faded as if on the wind. That is a fabulous conception, however, it doesn’t serve the themes that can resonate and should resonate with the audience, especially the men as they learn about women, a subject they often profess to know little about. Men above all need to know the “what” of women’s experiences.

Hamilton, Lin Manuel Miranda’s work is rapped quickly, exuberantly. However, each word is treated with “kid gloves,” to add a simile, like a diamond, or precious ruby. Each word is articulated, pronounced clearly, enunciated. Why aren’t Shange’s words treated like such jewels? Every word is vital to our understanding.

I wasn’t the only one frustrated by the performers rushing over the poetry to make the production come in at a certain time. In my section of the audience, humorous segments were missed. Sitting in the round the audience opposite us laughed. The same occurred when we laughed, the audience on the opposite side were silent. Great, if that is a symbolic/thematic notion. I understand, but don’t agree if that is the intentional direction.

Shange’s poetic phrases and word choices are heady. The performers are there to tell a story, to act and be heard and understood. What Shange is saying we must understand. All of it! Okwui Okpokwasili’s “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff…” was hysterical and deep, and the audience around me laughed and enjoyed that choreopoem because she slowed down, enunciated, paused, articulated; the same occurred with Adrienne C. Moore. And Alexandria Wailes’ signing was excellent and powerful. But some of the other women at times didn’t completely come through to us. That disappointed me because I loved the production’s energy and profound themes. Despite that caveat, it is smashing!

for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf runs with no intermission at the Public Theater until 8th December. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

,