Blog Archives

‘Ragtime’ is Magnificent and of Incredible Moment

Between the time Lear DeBessonet’s Ragtime graced New York City Center with its Gala Production in 2024, until now with the opening of DeBessonet’s revival at Lincoln Center, our country has gone through a sea change. The very core of its values which uphold equal justice, civil rights and due process are under siege. Because our democratic processes are being shaken by the current political administration, there isn’t a better time to revisit this musical about American dreamers. Ragtime currently runs at the Vivian Beaumont Theater until January 4.

DeBessonet has kept most of the same cast as in the City Center Production. The performers represent three families from different socioeconomic classes. In each instance, they face the dawning of the 20th century with hope to maintain or secure “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” in a country whose declaration asserted independence from its king. In affirming “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all ‘men’ are created equal,” America’s promises to itself are fulfilled by its citizens. Ragtime reveals who these citizens may be as they strive toward such promised freedoms.

Above all Ragtime is about America, the saga of a glorious and terrible America, striving to manifest its ideals and live up to them, despite overarching forces that would slow down and halt the process.

Based on E. L. Doctorow’s classic 1975 historical novel, and adapted for the stage by Terrence McNally (book), Stephen Flaherty (music), and Lynn Ahrens, (lyrics), Ragtime‘s immutable verities are heartfelt and real. As such, it’s a consummate American musical. DeBessonet’s production celebrates this, and superbly presents the beauty, tragedy and hope of what America means to us. In its concluding songs (Coalhouse’s “Make Them Hear You,” and the company’s “Ragtime/Wheels of a Dream”), the performers express a poignant yearning. Sadly, their choral pleading is a stunning and painful reminder of how far we have yet to go to thoroughly uphold our constitution.

The opening number “Ragtime,” introduces the setting, characters and suggested themes. Here, DeBessonet’s vision is in full bloom, from the lovely period costumes by Linda Cho, David Korins’ minimally stylized scenic design, DeBessonet’s staging, and Ellenore Scott’s choreography. As the company sings with thrilling power and grace, they gradually move forward to take center stage. They are one unit of glorious interwoven diversity and destiny. The audience’s applause in reaction to the soaring music and stunning visual and aural presentation, heightened by a bare stage, emotionally charged the performers. Thematically, the cast had an important mandate to share, a cathartic revelation of the sanctity of American values, now on the brink of destruction.

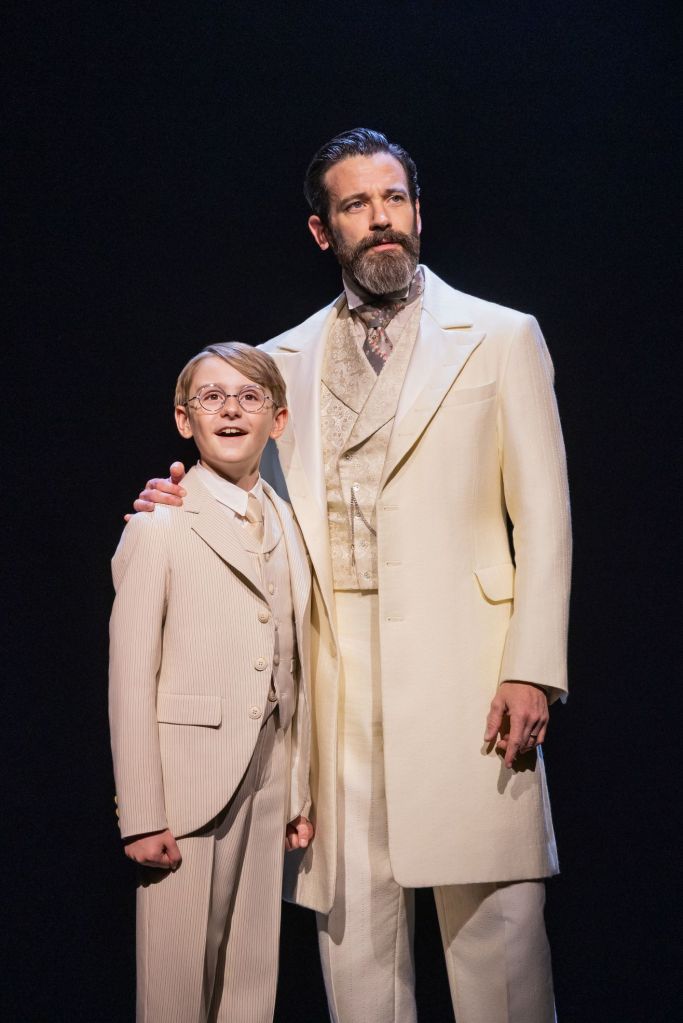

Watching the unfolding of events we cheer for characters like the talented Harlem pianist and composer of ragtime music, Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (the phenomenal Joshua Henry). And we identify with the ingenious, Jewish immigrant Tateh (the endearing Brandon Uranowitz). Tateh must succeed for the sake of his little daughter (Tabitha Lawing), despite their impoverished Latvian background. Likewise, we champion Mother (the superb Caissie Levy), who reveals her decency, kindness and skill, running the house, family and business. She must fill in the gap while her husband (Colin Donnell), goes on a lengthy expedition to the North Pole as a man of the privileged, upper class patriarchy.

The musical also reflects the other side of America’s blood-soaked history, best represented by characters along a continuum. Their misogyny, discrimination and greed often overwhelm, victimize and institutionalize innocents in the name of a just progress. These include tycoons like J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford, and the garden variety racists that brutalize Coalhouse Jr. and his partner Sarah (the fine Nichelle Lewis), in the name of order and security. Finally, to inspire all, the musical includes wily entrepreneurs like Harry Houdini (Rodd Cyrus), social justice advocates like Emma Goldman (the wonderful Shaina Taub), and accepted reformers like Booker T. Washington (John Clay III). All these individuals make up the living fabric of America.

At its most revelatory, Ragtime exposes elements of our present as the continuation of entrenched issues never resolved from our past. Despite our great strides in nuclear fission and quantum computing, retrograde darkness still lurks in the nation’s beating heart, in its violence, in its human rights inequities. Clear-eyed, incisive, DeBessonet’s spare choices about spectacle and design, and her focus on great acting and singing by the leads and ensemble, ground this masterwork.

Ragtime begins with an interesting unexplained entrance: a winsome and beautiful Black male child in period dress frolics across a bare stage. At the conclusion the circle comes to a close and he appears again. We discover who he is and what he symbolizes in a stark, crystallizing moment of elucidation. After the opening number (“Ragtime”), Mother’s adventure as head of her household begins when Father leaves (“Goodbye My Love”). Her helpers include her outspoken, prescient, son Edgar (Nick Barrington), her younger brother (Ben Levi Ross), and her opinionated, crotchety father (Tom Nelis).

However, the peace and serenity of their lives become interrupted when Mother discovers an abandoned baby in her garden. After much deliberation, Mother takes in the infant and traumatized mother, Sarah. Clearly, this startling act of redemption never would have occurred if Father was present. As an assertion of Mother’s right to make her own decisions, her grace becomes a turning point in the lives of the baby’s father, Coalhouse, and his love, Sarah. Apparently, Coalhhouse left Sarah to travel for his career, not knowing she was pregnant. He was pursing his dream of being a singer/composer of the new ragtime music.

By he time Coalhouse searches for Sarah to eventually find and woo her back to him, we note the tribulations of Tateh, who tries to survive using his artistic skills (like Harry Houdini). And we note the moguls of a corrupted capitalism, i.e. Ford, Morgan (“Success”), who Emma Goldman accuses of exploitation. They keep the workers and society oppressed and poor.

Using his charm and daily persistence (“he Courtship,” “New Music,”), Coalhouse wins Sarah back. In a dramatic, dynamic moment, Henry’s Coalhouse sings with emotion, “Sarah, come down to me.” When Lewis’ Sarah descends, their fulfillment together is paradise. The stunning scene like the ones that follow, i.e. “New Music,” and especially Henry and Lewis’ “Wheels of a Dream,” where Coalhouse and Sarah sing to their son about America, are hopeful and heartbreaking. Again, the audience stopped the show with applause and cheers as they periodically did throughout the production.

On the wave of Coalhouse and Sarah’s togetherness and love reunited, we forget the underbelly of a dark America that looms around the corner. It does appears during Father’s reunion with Mother after his lengthy voyage.

Unhappily, Father returns to a household in chaos with Sarah, Coalhouse and the baby under his roof. He can’t imagine what “got into” his wife and makes demeaning remarks about the baby. His conservative, un-Christian-like attitude upsets Mother. She defends her position and replies with demure, feminine instruction. Interestingly, her comment indicates she will not heel to him like the good lap dog she was before he left. As with the other leads, Levy’s performance is unforgettable in its specificity, nuance and authenticity.

Clearly, the characters have made inroads with each other bringing socioeconomic classes together during events when activists like Emma Goldman and Booker T. Washington make their mark and reaffirm equality. As a representative of the wave of immigrants coming to America from other teeming shores, Uranowitz’s Tateh steals our hearts and pings our consciences, thanks to his human, loving portrayal. Despite his bitterness in having to brace against the poverty he came to escape, he tries to overcome his circumstances and with ingenuity and pluck continually perseveres. Uranowitz’s Tateh particularly makes us consider the current government’s cruel, unconstitutional response toward migrants and immigrants today.

Act II answers the conflicts presented in Act I, leaving us with a troubling expose of our country’s heart of darkness. Yet, the musical uplifts bright halos of hope with the return of the adorable Black male child. We discover who he is and understand his mythic symbolism. Also, we learn the fate of the characters, some justly deserved. And the audience leaves remembering the cries of “Bravo” that resounded in their ears for this mind-blowing production.

Ragtime

With music direction by James Moore Ragtime runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission through Jan. 4 at the Vivian Beaumont Theater lct.org.

‘The Shark is Broken’ Three Men Missing a Shark, Broadway Review

Much of the real terror related to the film Jaws (1975), was experienced behind the scenes. The film was over budget $2 million and its flawed premise needed correction because the star of the picture, Bruce (the monster great white shark), was unworkable. To add insult to injury, director Steven Spielberg and the main cast were unproven at the box office and had issues to overcome. Finally, there was no finished script. For all intents and purposes, the film looked to go belly up, just like the three versions of mechanical Bruce, who foundered, sputtered and sank forcing the director and writer John Milieus into extensive rewrites.

However, Hollywood is the land of miracles. Jaws (adapted from Peter Benchley’s titular novel), broke all box office records for the time, despite the frankenfish never really “getting off the ground” the way Spielberg intended.

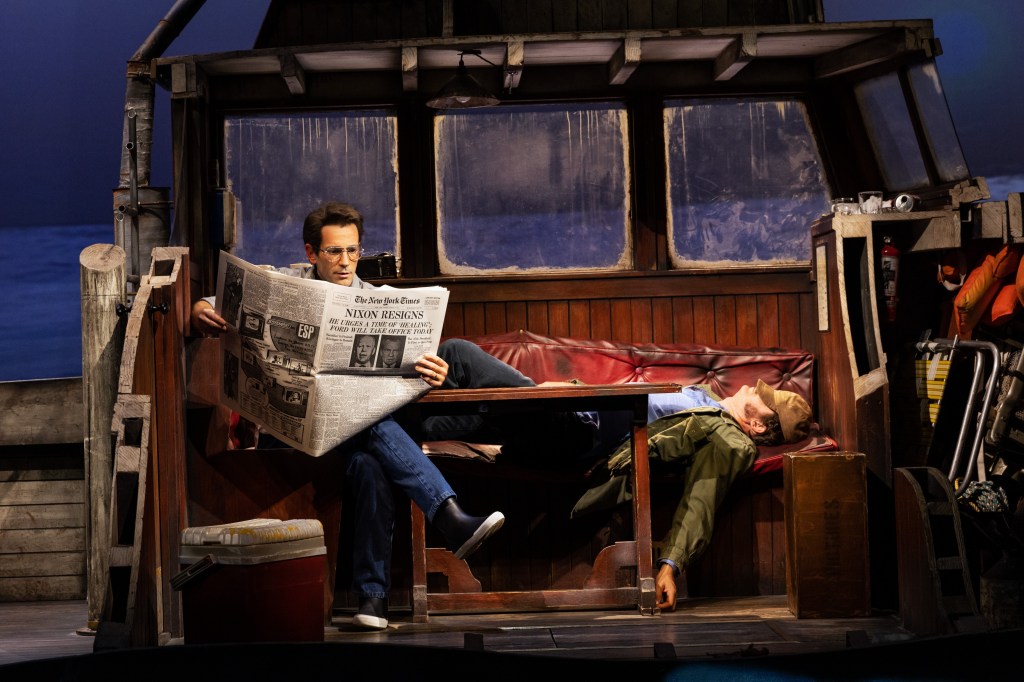

The Broadway show The Shark is Broken, currently sailing at the Golden Theatre until the 19th of November is the story of the three consummate actors behind the flop that might have been Jaws if Spielberg and his team didn’t rethink their broken monster, proving less screen time is more powerful when the shark finally shows up. The amusing play co-written by Ian Shaw (Robert Shaw’s son) and Joseph Nixon, and directed by Guy Masterson comes in at a slim 90 minutes. It features Alex Brightman (Beetlejuice the Musical) as Richard Dreyfuss, Colin Donnell (Almost Famous at The Old Globe) as Roy Scheider, and Ian Shaw (War Horse), who plays his father Robert Shaw.

The play focuses on these three actors who attempt to deal with the circumstances and each other as they try to make it through the tedious days waiting for Bruce, the real star, to “get his act together.” However, Bruce never does. Indeed, if one revisits the film, one must give praise to the superb performances of Dreyfuss, Scheider and Shaw who make the audience believe the shark is horrifically real and not a broken-down, mechanical “has been.”

Crucial to the film’s success are the dynamics among the actors which The Shark is Broken highlights with sardonic humor and a legendary sheen. Once the film skyrocketed to blockbuster status, the high-stress problems surrounding the film’s creation could be acknowledged with gallows humor. Such is the stuff that Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon configure as they reveal intimate portraits of the actors’ personalities, foibles, desperations and bonding, while waiting for their “close-ups” with Bruce. Though the play appears “talky,” the tensions and undercurrents form the substance of what drives the actors. Like a shark that glides with fin above water, what lies inside each of the actors threatens to explode when least expected.

Even seemingly mild-mannered, emotionally tailored Scheider flips out. When his luxurious sun bathing is curtailed and his presence demanded on set, Donnell takes a bat and smashes it on the deck in fury. Donnell has no dialogue but his actions and body speak louder than words and we see how underneath that calm demeanor, Scheider is capable of potential violence which he keeps on a leash and, like a dog, gets it to heel when he wishes.

Based on Robert Shaw’s drinking diary, family archives, interviews and other Jaws‘ sources, Shaw and Nixon pen an encomium to the actors’ efforts and relationships forged during their claustrophobic time spent on the Orca, which floated on the open ocean east of Martha’s Vineyard between East Chop and Oak Bluffs. As the actor-characters arrive, we note the resemblances to their counterparts, further emphasized by their outfits, (costumes by Duncan Henderson), speech (dialect coach-Kate Wilson), and mannerisms.

Donnell is the fit, tanned, attractive, temperate Scheider, well cast to portray police chief Brody, head of the shark expedition. Brightman is the pudgy, scruffy, angst-filled Dreyfuss, who sounds and looks like the actor, and is filled with brio and insecurity as Ian’s Shaw batters his ego. As a dead-ringer, Ian portrays his father Robert Shaw, who merges the steely-eyed, gravely voiced, hard-drinking Quint with himself so the boundary between actor and character is seamless. Ian’s Shaw is comfortable in his cap and jacket ready to conquer his prey which includes the poorly written Indianapolis speech, and Richard Dreyfuss.

Thanks to the creative team, Duncan Henderson’s set and costume design, Campbell Young Associates wig design and construction, Jon Clark’s lighting design, Adam Cork’s sound design and original music, and Nina Dunn for Pixellux’s video design, the scenes when the three are on the Orca waiting for the great white to arrive include the manifested cross section of the boat interior, undulating ocean with seagulls flying overhead, wave washing sound effects, sunsets, and a lightening storm during which Ian’s Shaw stands rocking near the boat railing as he challenges the storm. The designated force of Robert Shaw comes through particularly, as he stands arms outstretched, back to the audience, accepting whatever the chaotic, dangerous elements unleash on him.

What do these men do to redeem the time as they wait for one of the three versions of Bruce to be commissioned to work? They do what sailors have done time immemorial: play innumerable card games, read the newspaper, play pub games and verbally and physically attack each other parlaying wit, wisdom, insults and choking. The latter occurs when Brightman’s Dreyfuss calls Shaw’s bluff about giving up drinking. With a quick maneuver, Dreyfuss takes Shaw’s bottle and tosses it over the side, a severe cruelty for a drinking man. Ian’s Shaw leaps into ferocity. It is only Scheider’s peacemaking and his threat that Shaw will be sued for delaying the film further, that remove Shaw’s ham hands from Dreyfuss’ quivering throat.

The feud between Dreyfuss and Shaw is exacerbated by inaction and the actors’ boredom between scene takes. This gives rise to the competitive hate/love emotions between the two men, which escalate during the play and are a fount of scathing, sardonic humor. When confronted about it, Shaw insists he is helping to improve Dreyfuss’ performance, and indeed, the tension between the actors behind the scenes travels well to their portrayals on film. The thrust and parrying of epithets and wit, which Scheider attempts to mitigate to no avail, forms the backbone of the dialogue which comes at the expense of Dreyfuss’ savaged ego.

Shaw, a noted writer and giant on the stage, sharpens his wordplay on Dreyfuss’ attempts at rebuttal. It is only after a quiet moment between Scheider and Shaw when Scheider tells Shaw how much Dreyfuss admires him, that Shaw lets up, but only a bit.

Son Ian is not shy about his father’s alcoholism and he plays the role as if he was familiar with how crusty and gritty his father could get when he was “three sheets to the wind.” Though he lost him at a young age and most probably doesn’t remember him all that well, the point is made that alcoholism and loss is generational. Robert Shaw shares that he lost his father to suicide when he was a youngster and always rued that he could never assure his dad that things would be all right. By that point his father had killed himself. Robert Shaw also died young and left his nine children wanting him. Thus, homage is paid by Ian to his grandfather and father who both battled alcoholism and died before their sons could really know them.

At its most revelatory, The Shark is Broken is about fathers and sons and how their father’s abandonment and/or rejection traumatized the actors who struggle to get out from under the sense of loss, rejection and insecurity. Dreyfuss shares that his father left the family and wanted him to be a doctor or lawyer. Scheider reveals his father disdained his acting career, until he eventually accepted it and became proud of his son. It is the few shared moments like these where the men bond and find common ground that are strongest and wonderfully acted. The play might have used more of these moments and fewer attempts at ironic jokes about how Jaws won’t be memorable in film history.

Shaw’s reductio ad absurdum of the future of films as a measure of sequels: sequels will beget sequels of sequels that have sequels rings true, of course. But the statement for humorous purposes is far from prescient.

The Shark is Broken premiered in Brighton, England, went to a 2019 Edinburgh Festival Fringe run then opened on the West End before it arrived on Broadway. The play is humorous and entertaining with some missed opportunities for quiet, soulful moments. Certainly, those who have seen Jaws and its sequels will have fun and enjoy the near replica of the Orca and its inhabitants for a captured moment in film history made alive. The acting is crackerjack and Ian’s interpretation of the Indianapolis speech, which Shaw wrote himself, is at the heart of the film. As Ian delivers it, it is at the heart of the play and symbolically profound.

The Shark is Broken runs without an intermission at the Golden Theatre (252 West 45th Street). For tickets and times, go to their website https://thesharkisbroken.com/