Blog Archives

‘The Blood Quilt,’ Threading an Ancestral Masterpiece of Hope

The Blood Quilt

In her ambitious layering of the story of four half-sisters who gather to finally lay to rest their recently deceased mother, Katori Hall, with astute direction by Lileana Blain-Cruz, focuses on complex family dynamics, jealousies, misunderstandings and secrets. The confluence of emotions roil the souls of each sister and a teenage niece, paralleling the stormy seas which crash waves onto the setting, Kwemera Island, Georgia. The culmination of fiery anger, pain and sadness releases in the rituals of quilting and the soul healing of family connections in mysticism, dance and song.

By the conclusion of the two-act drama, currently at LCT’s Mitzie E. Newhouse until December 29, we know the fabric of each of the sister’s lives. As a result we thrill with them when they are able to reconcile their inner wounds and cast them into the sea. It is in the waters fronting the small country cabin they call home, where ancestors have been buried in a symbolic tradition that the eldest sister Clementine speaks of with power, “We all came from the water and we all must return.”

The characters are the patchworks that make up the family masterpiece

Much of the beauty of Hall’s drama, laced with comedic elements, comes from her precise characterizations of the disparate sisters who share the same mother but have different fathers. They are the patchworks that make up the last quilted masterpiece that their mother designed and they gather to finish.

Clementine, Gio, Amber

Clementine (Crystal Dickinson), is the eldest, who lives in the incredible ancestral home. Adam Rigg’s set design hums with authenticity, warmth and life. The cabin is decorated with generational family quilts that cover walls and the balcony railing, each colorful, individual, symbolic. Family ownership of the “chic” cabin with the sea in its front yard is in jeopardy because of unpaid taxes which their mother ignored, while keeping her delinquency a secret from her children.

Clementine, who lives there and became caretaker of their dying mother, best knows the rituals of their Jernigan ancestors. A root worker of potions and spells, she speaks Geechee (from their Gullah Geechee heritage), and emotionally archives their legacy, back to the first slave ancestors that lived and worked on the plantations in the area. She is a master of the rituals and celebration of their heritage through quilting which they practice yearly under her direction. This summer when the play opens, the sisters and their niece Zambia (Mirirai), gather together to complete the last quilt their dying mother/grandmother designed, as they symbolically release her to another plane of existence.

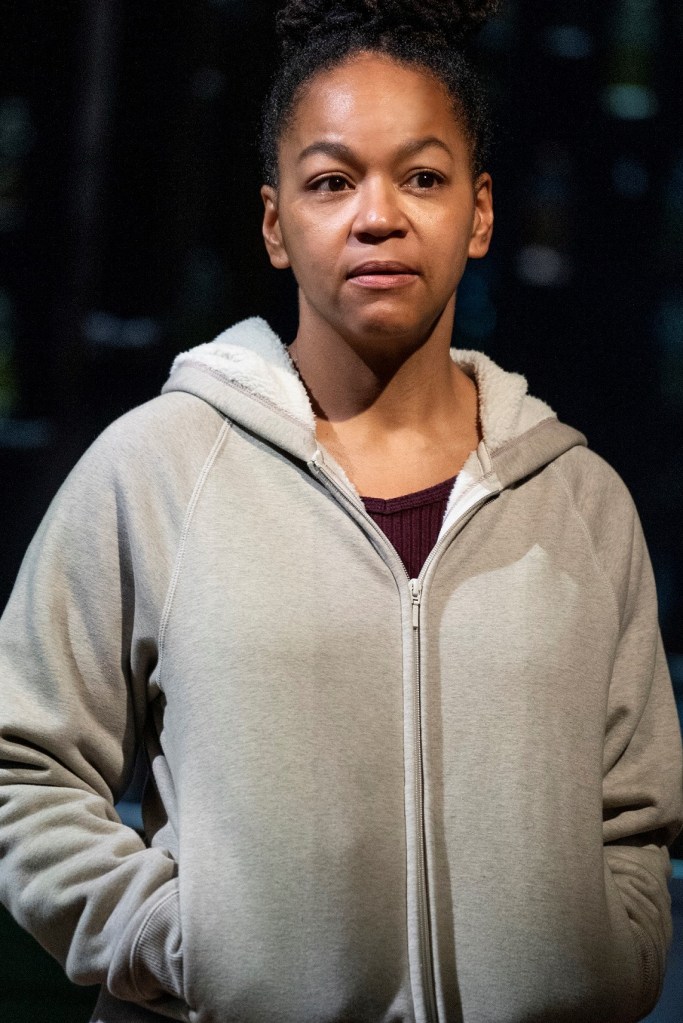

Gio (Adrienne C. Moore), is the second oldest, a roughly hewn, hard drinking, Mississippi cop, who is resentful and jealous of her youngest sister Amber (Lauren E. Banks). Gio’s rancor runs deep because of a traumatic, covert incident unbeknownst to Amber but related to Amber’s father that happened when Gio was a teenager. Sensitive to her own misery, burying hurts from her divisive relationship with their mother who abused her, Gio’s moods, aided by alcohol, swing widely as she peppers them with spicey swearing and insults directed mostly at youngest sister Amber.

Amber is the beauty and reputed favorite of their mother because of her accomplishments. She went to an Ivy league college and eventually becomes an entertainment lawyer of means. Because she missed the last three summers of their quilting ritual, and their mother’s funeral service, her estrangement from her sisters and the difference between her lifestyle and theirs is apparent.

Despite Gio and Clementine’s “guilting” her for not coming to the funeral, we discover Amber was emotionally the closest to her mother. She paid for her cancer treatments, phoned her often and even assisted the family after she left the homestead for California. In spite of their geographical and emotional separation, she paid for her sisters’ needs when they asked her, and especially pays for niece Zambia’s tuition in a private school.

Zambia and Cassan

It is Zambia who is the linchpin of the wayward, patchwork family that hangs together by a slender thread as each sister expels her angst and self-recrimination to each other. However, Hall uses Zambia and her mother, the quiet nurse Cassan (Susan Kelechi Watson), who is the closest to Amber, to round out the backstory with Zambia’s questions. Zambia and peacemaker Clementine move along the arc of development which settles upon two issues. How will they pay off the tax liens against the house, and who inherits the quilts, (pricey relics which are cultural artifacts of a rich historical past), the property and the cabin contents?

These questions are answered as Hall unspools each sister’s interior wounds via their relationships, revealing their individual portrait of their complicated, intriguing mother. All clarifies and we are brought to the edge of unresolved personal traumas that threaten to further destroy their lives emotionally, physically, spiritually. However, it is the act of quilting together that we view the whole with the sisters contributing to the corners of the ancestral masterpiece that unifies them with a familial love and redemption from past harm effected by their mother, each other and most importantly themselves.

Mystical elements

Hall’s first act languishes in exposition until the conflicts among the sisters erupt. The details of the quilting process fascinate and are well integrated into the dialogue. The symbolism and metaphor of the stormy souls aligned with the threatening hurricane’s thunder and lightening effected by Jiyoun Chang (lighting design), Palmer Hefferan (sound design), and Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew (projections), mirror how the natural world, material world and spiritual world often collide until there is a movement toward establishing peace and reconciliation.

Blain-Cruz does a smashing job referencing the impact the spiritual plane of existence has upon the material life of the sisters which is sensationally wrought in Act 2 toward the conclusion when they attempt to place the finished quilt on their mother’s bed and a mystical experience occurs. It is then when Zambia becomes the channel between the past spiritual legacy and the present and the pathway toward healing is realized.

The costumes by Montana Lvi Blanco pointedly imbue each of the sisters and Zambia’s changing “trends,” enhancing Hall and Blain-Cruz’s vision of this family to precisely tie in their characters culturally and psychically. Importantly, the ensemble works together to create a family drama with which we can identify and empathize. Their acting is superb. Perhaps the Geechee deserves a translation either in the program or elsewhere. I was benefited by a copy of the script. Vitally, the different language serves to remind the audience of the African diaspora that beleaguered the Jernigan ancestors-slaves, and unified them as they prospered in a hostile, alien world.

The Blood Quilt

See The Blood Quilt, which runs two hours forty-five minutes with one intermission at LCT, the Mitzi E. Newhouse, until December 29th.

,

‘Cullud Wattah’ The Flint Water Crisis, Advocacy Theater at Its Best

Flint, Michigan’s water crisis is ongoing as Erika Dickerson-Despenza clearly establishes in the world premiere production of Cullud Wattah currently at The Public Theater. Directed by Candis C. Jones, the play is evocative, heartfelt and praiseworthy in its power to shock and anger the audience, as it clues them in to the Cooper family’s stoic struggles to get to the next day. Their trials become more arduous and earth-shattering as they confront the irreparable contamination of their water supply that is slowly killing them because they were notified too late by city and state officials of its toxicity.

Dickerson-Despenza gradually evolves the situation acquainting us with three generations of the Cooper family of women, who live in the house that Marion (the edgy Crystal Dickinson) and her deceased husband purchased through their hard work at the GM plant which outsourced, downsized and ended his job. Thus, to make money, her husband joined the military where he was later killed in the U.S. war with Afghanistan.

Living in the Flint house with Marion are her mother, Big Ma (the humorous and no nonsense Lizan Mitchell), her pregnant sister Ainee (the superb and empathy evoking Andrea Patterson), and Marion’s two daughters Plum, the totem-like representative for all Flint’s younger children, portrayed by Alicia Pilgrim, and Reesee. As Reesee, Lauren F. Walker delivers an apt portrayal of the strong, self-determined older daughter, who loses faith in her relationship to the Yoruba water goddess Yemoje. The Yoruba water goddess doesn’t make good on her promise to protect the family from hardship and injury.

Dickerson-Despenza’s work is culturally powerful. Her characters establish their ancestry through dialect and dialogue using an easy Black accented speech, save Marion who has been influenced and perhaps soulfully compromised by working at the General Motors plant for most of her life.

Though General Motors has provided opportunity, it has been responsible for abusing its employees when they protested for better working conditions and wages. During the play Ainee reminds Marion that GM polluted the Flint River for years and abusive workers (members of the Klan) killed their father and took vengeance out on their mother, Big Ma, for her work actions against the company. These work actions left Big Ma disabled.

Through family discussions of the crisis, with the news Big Ma listens to running in the background, the facts of the dangerous situation are manifest. City and state officials are accountable for switching the water supply to the toxic Flint River from Lake Huron, fulfilling their campaign promise to “save money.” Their platform for reelection (fiscal responsibility), did the opposite negligently and incompetently. They discounted that the Flint River had been polluted with toxic sludge from GM for years.k The water was completely undrinkable and unusable. However, since the water was mostly going into the black community and since that community contributed less in property taxes, officials wantonly ignored the danger lurking in their unresearched, inherently racist and negligent actions.

Interestingly, the city and state grew a conscience when GM noted that the water needed for their industrial process to build engines was corroding and destroying their product and bottom line. GM screamed to change the water back to the clean Lake Huron water source. Avoiding GM’s closure or litigation to sue for damages, Flint city officials and the state of Michigan responded. However, only GM received the clean water.

When word of the situation leaked, city officials and then Republican Michigan Governor Rick Snyder wickedly lied. They declared the water was safe to drink. Their lies killed, destroyed families and cost billions of dollars in medical bills and future liabilities for sick adults and children. The financial burden to educate and medically care for young children brain damaged by lead poisoning and confronting other ills (cancer) from the water is ongoing and especially egregious. The cost to Michigan and the entire nation is many millions more than the money “saved” by switching water supplies.

We learn during the play that Marion, knowledgeable about this situation at GM, withholds the secret from her family. Though she attempts to bring the clean water from GM to their home, it is too late. Eventually, her silence backfires on her through Plum’s sickness and the ill effects of rashes, hair loss and other conditions the family endures from being poisoned by the toxic soup coming from their faucets.

Dickerson-Despenza uses Ainee as the foil in the arguments supporting the “good” that GM did for Flint versus their criminal behavior. They didn’t protect their workers and they committed abusive acts against the union. Ainee’s stance is an indictment against GM and the workers who allowed themselves to be compromised and exploited. She argues with Marion that she owes GM nothing, and must become involved in a Class Action lawsuit against the city and officials for their negligence and responsibility in decimating the Flint community by not warning them about the toxic water.

As the situation unfolds, we learn how each of the women respond in dealing with the crisis on a personal level and as a member of the Cooper family. Ainee attempts to become an activist, though this runs counter to Marion who is moving up at GM, despite their initial attempt to lay her off. How Marion manages to finesse herself an opportunity is revealed later in the play.

Marion’s daughter Reesee attempts to keep sane during the crises by praying and giving offerings to the Yoruba goddess of water which she reveals to Plum as a secret because Big Ma is religious and doesn’t approve of black folk gods. Plum attempts to take control of the situation with her mathematical skills, figuring out how much daily water they need for each of their activities.

Big Ma prays to the Christian God and helps with the chores and generally chides each of them if they step over the line of decency, especially with regard to vulgar language. However, the rock of the family is Marion. She is the only one able to work. She takes care of their financial burdens with no help from the others and is pressured by their debts: Plum’s medical bills, the upkeep of the house, their great quantity of water purchases, utilities and more.

The playwright’s details about the bottles of water required to wash vegetables, the turkey and trimmings for Thanksgiving dinner, the water needed to clean and take care of their daily needs is a staggering reminder of how much water we use in our lives. Wherever you turn in the theater, you see the reminder of the importance of clean water via Adam Rigg’s wonderful set design. Through Plum, who is dying because of the corrupted water, we note the numbers. At the play’s beginning, she chalks off the days Flint’s water supply has been corrupted since 2014: it is in the thousands surrounding the walls of the theater. On sides of the stage, Riggs has suspended bottles of water hanging down against the walls. It looks clean, but is it? The stage is filled with bottles of yellow, toxic water that the women label as a record that their water supply is still contaminated.

Dickerson-Despenza’s themes are paramount, ironically timeless as well as politically current. What happens when an elite power structure controls the resources all of us need to thrive? What happens if the corporate elites are discriminatory, partisan, bigoted killers at heart? What happens if the people in powerful government positions are those they pay off to continue destroying the communities they despise, the voices that must be heard, but are killed off to keep them silent and the power structure intact? Is this institutional racism at work or is it random, an example of the banality of evil?

Cullud Wattah is essentially a play about water as a life source spiritually, psychically and materially using the horrific backdrop of Flint, Michigan to show how Republicans and corporates (represented by GM) amorally decimated the black community with impunity safeguarded by bought corporate-backed politicos for decades. Breaking down the will, soul and spirit of a community, oppressing it, makes it easier for politicians and their donors to overcome their righteous voices and resistance. Soon, unable to maintain and uphold their rights in a country whose laws guarantee “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” but don’t judicially, oppressors to staunch their rights, their democracy, their one voice one vote. Thus, corporates compromise democracy weakening the laws that protect citizens.

Dickerson-Despenza leaves no stone unturned in claridly, unapologetically dramatizing the painful, terrible crimes against humanity represented by the Cooper family as a microcosm of the macrocosm. The abomination not only concerns Flint, Michigan, it threatens every community in the US and every global town and city. The higher ups briefly mentioned on Big Ma’s newscasts are as invisible in the play as a clear glass of water looks clean. You have to get up close and examine the molecular structure to note the contamination, corruption and poisonous, corrosive toxicity.

Dickerson-Despenza’s vision for this production is acute and profound. Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew’s lighting design and Sinan Refik Zafar’s sound design and composition includes a digital blow up of the litigation against the city and state officials. That the blow up of the litigation is not visibly large enough for the back row to see the fine print is symbolic. Such litigation is not enough to compensate the Cooper family for what they have endured in psychic and emotional suffering. And indeed, lengthy jail terms for the Republican officials, including the former disgraced Governor Snyder, must be leveled, if not as a deterrent to Republicans seeking positions of power to line their pockets, but as a warning for citizens to not elect such wanton, miscreant criminally minded individuals, regardless of political party.

To elect moral, efficacious officials, one has to bring out a microscope and “test the waters.” With the lies politicos glibly use to get elected, and the collusion between them and corporations to abuse the public trust and communities where they settle, this appears to be impossible. However, thanks to Republicans, you can see whether the water is clean or dirty and can assess if the politicians have the public’s interest at heart. Republican extremists which govern their party are making it very obvious that their water is filthy and toxic. Like the former governor of Michigan, they have made their intentions and will crystal clear.

Cullud Wattah covers much ground and speaks volumes about victims, activists and the unseen criminal politicos who abuse their citizens. In its unabashed indictment of racism that emerges from the discussions and conflict between Ainee and Marion, are the warnings. If this happens in one community, it can happen in every community, because certain parties don’t care who is hurt, who dies as long as they 1)make money 2)get away with murder. The title is symbolic inferring the beautiful spirit and resilience of these women who are black. Of course, it refers to Flint’s water which is yellow, and the fact that officials criminally saw “fit” to let the blacks (the cullud) drink it, a hate crime which the federal government must address.

The play is heartbreaking with terrifically current themes. The particular irony and idiocy of white supremacists is that they believe their bought “Republican” politicians will always have their best interests at heart. Those white folks who lived in Flint also drank contaminated water and suffered, but predominately, the black community was hit: this is a crime of federal proportions.

Polluted water, like COVID, is not subject to race. Regardless of your heritage, you get sick. Polluted politicians are subject to race to get elected. Once in office, in their amoral perspectives, the election gives them the legitimacy and impunity to harm citizens regardless of race, creed, religion. But the truly wicked ones unleash their hatred on specific communities, deemed to be too “weak,” to protest and be heard. Flint is emblematic of this. It is to her great credit that Erika Dickerson-Despenza’s Cullud Wattah, its director Candis C. Jones, the wonderful actors and the astute creative team brought this play to The Public. It needs to be seen across the U.S.

Kudos to the creative team not heretofore mentioned: Kara Harmon (costume design), Earon Chew Healey (hair, wigs and makeup design). Cullud Wattah is a must see that runs until December 12th at the Public Theater. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.