Blog Archives

‘Liberation’ Transfers to Broadway Solidifying its Excellence

Bess Wohl’s Liberation directed by Whitey White in its transfer to Broadway’s James Earl Jones Theater until January 11th doesn’t add references to the 2024 election nor the disastrous aftermath. However, the production is more striking than ever in light of current events. It reaffirms how far we must go and what subtle influences may continue to derail the ratified ERA (Equal Rights Amendment) from becoming settled law.

To draw parallels between the women’s movement then and now, Wohl highlights the “liberation” of the main character/narrator Lizzie, an everywoman, with whom we delightfully identify. With Lizzie (the superb Susannah Flood) we travel along a humorous journey of memory and self-reflection as she evaluates her relationship to her activist mom, who gathered with a community of women in Ohio, 1970 to “change the world and themselves.”

Wohl’s unreliable, funny narrator, directs the action and also is a part of it. The playwright’s smart selection of Lizzie as a device, the way in to tell this elucidating story about women evolving their attitudes, captures our interest because it is immediate. Her understanding is ours, her revelations are ours, her “liberation” is also ours. Lizzie shifts back and forth in time from the present to 1970-73, and back to the present. One of the questions she explores concerns why the women’s movement cascaded into the failures of the present?

Assuming the role of her mother, Lizzie enacts how her mom established a consciousness-raising group. Such groups trended throughout the country to establish community and encourage women’s empowerment. Six women regularly meet in the basement basketball court at the local rec center which serves as the set throughout Liberation, thanks to David Zinn’s finely wrought stage design. The group, perfectly dressed in period appropriate costumes by Qween Jean, includes a Black woman, Celeste (Krisolyn Lloyd), and the older, married Margie (Betsy Aidem).

Having verified stories with her mom (now deceased), and the still-living members of the group, Lizzie imagines after introductions that the women expansively acknowledge their hope to change society and stand up to the patriarchy. As weeks pass they clarify their own personal obstacles and their long, bumpy road to change, with ironic surprises and setbacks.

For example, Margie voices her deeper feelings about being a slavish housewife and mother. After months of prodding, her husband actually does the dishes, a “female” chore. Margie realizes not only does she complete housework faster and better than he, but her role as housewife and nurturer satisfies, comforts and makes her happy. Betsy Aidem is superb as the humorous older member, who introduces herself by announcing she joined, so she wouldn’t stab her retired husband to death.

Some members, like Sicilian-accented Isidora (Irene Sofia Lucio), and Lloyd’s Celeste, belonged to other activist groups (e.g. SNCC). Circumstances brought them to Ohio. Isidora’s green-card marriage needs six more months and a no-fault divorce, not possible in Ohio. Celeste, a New Yorker, has moved to the Midwest to take care of her sickly mom. The role of caretaker, dumped on her by uncaring siblings, tries her patience and stresses her out. Expressing her feelings in the group strengthens her.

Susan (Adina Verson) is an activist burnt out on “women’s liberation.” Frustrated, Susan has nothing to say beyond “women are human beings.” She avers that if men don’t treat women with equality and respect, then women’s activism is like “shitting in the wind.”

Lizzie and Dora (Audrey Corsa) discuss how they suffer discrimination at their jobs. Despite her skill and knowledge Lizzie’s editor demeans her with “female” assignments (weddings, obituaries). Dora’s boss promotes men less qualified and experienced than Dora. Through inference, the playwright reminds us of women’s lack of substantial progress in the work force. Very few women break through “glass ceilings” to become CEOs or achieve equal pay.

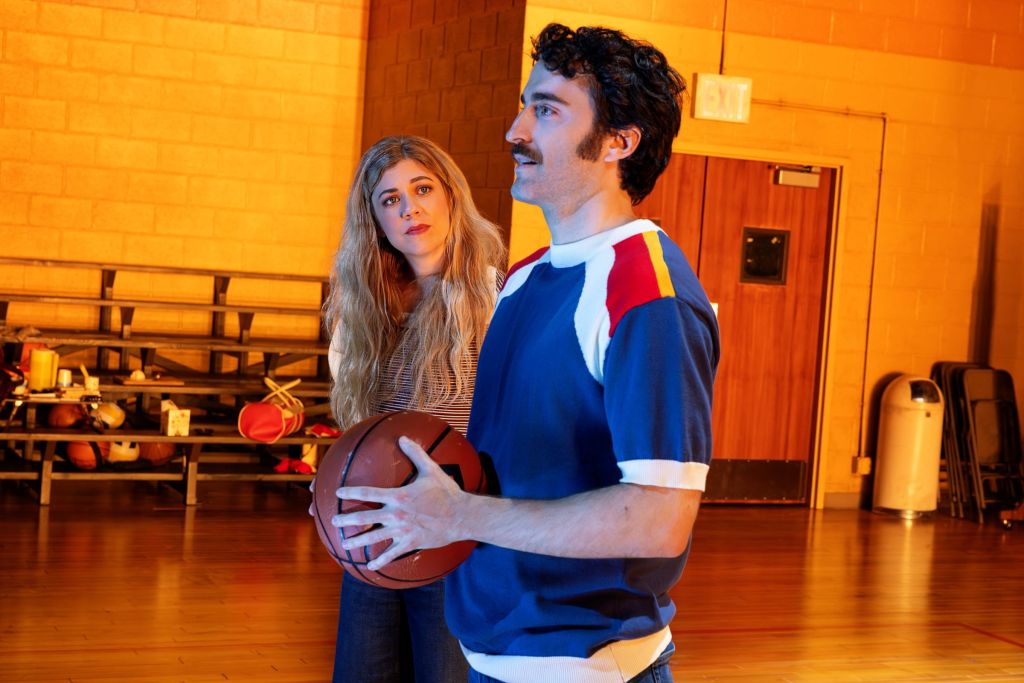

Act I engages because of the authentic performances and various clarifications. For example, Black women have a doubly difficult time at overturning the patriarchy. Surprisingly, at the end of the act a man invades their space and begins shooting hoops. Is this cognitive dissonance on Lizzie’s part for including him? Have women so internalized male superiority that they become misdirected back to the societal default position of subservience? Is this what thwarted the movement?

When Lizzie refers to the guy as Bill, her father (Charlie Thurston), we get the irony. How “freeing” that her mom meets her dad as she advocates for liberation from male domination, only to be dominated by an institution (marriage) constructed precisely for that purpose.

Act II opens with additional dissonance. To extricate themselves from the psychological trauma of men’s objectification of their bodies, the women free themselves from their clothes. Sitting in the nude, each discusses what they like and dislike about their bodies. The scene enlivened heterosexual men in the audience, an ironic reinforcement of objectification. We understand that these activists try to overcome body shame that our commercial culture and men use to manipulate women against themselves and each other (surgical enhancements, fillers, face lifts, etc.). On the other hand the scene leaves a whiff of “gimmick” in the air, though Whitney White directs it cleverly.

After the nude scene Lizzie reimagines how her mom and Bill fell in love. To avoid discomfort in “being” with her father, she engages Joanne (Kayla Davion), a mother who drops into the rec room looking for her kids’ backpacks. Through Bill and Joanne’s interaction, we note the relationship that Lizzie keeps secret. When Lizzie finally reveals she is engaged, the dam bursts and each of the women reveals how they have been compromising their staunch feminist position. One even admits to voting for Nixon with a barrage of lame excuses.

This scene is a turning point that Lizzie uses to explore how women in the movement may have sabotaged themselves at advancing their rights. Reviewing her mother’s choice to get married and co-exist as a feminist and wife, Lizzie reimagines a conversation with her deceased mother played by Aidem’s Margie in an effecting performance. When Lizzie asks about her mom’s happiness, Margie kindly states that Lizzie has gotten much of her story wrong.

Lizzie condemns feminism’s failures. This is the patriarchy, internalized by Lizzie, speaking through her. With clarity through Margie’s perspective, Wohl reminds us that all the stages of the feminist movement have brought successes we must remember to acknowledge.

Lizzie realizes the answer to whether one might be “liberated” and fall in love and “live equitably” within an institution which consigns women to compromise their autonomy. It depends upon each individual to make her own way. Her investigation about her mother’s consciousness-raising group establishes the first steps along a journey toward “liberation,” that she and the others will continue for the rest of their lives.

Liberation runs 2 hours, 30 minutes with one intermission at the James Earl Jones Theater through Jan. 11th. liberationbway.com

‘Slave Play’ by Jeremy O. Harris, An Explosive, Archetypal Look at Power, Sadomasochism and Oppression Through the Mythic Lens of “Black” and “White”

(L to R): Ato Blankson-Wood, Chalia La Tour, Joaquina Kalukango (kneeling), Irene Sofia Lucio, Sullivan Jones, Annie McNamara, Paul Alexander Nolan, and James Cusati-Moyer. in ‘Slave Play’ by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (Matthew Murphy)

Slave Play by Jeremy O. Harris is a mind-bending, brain-slamming earthquake which will strike your soul and disturb you emotionally. Despite your desire to remain unaffected, you will react. Good live productions stir us. The finest plays rock us off our complacency and shatter our intellectual stasis. Slave Play, directed by Robert O’Hara, currently at the Golden Theatre, does that and more. Memorable and profound, it is the epitome of its sardonic genre. And in its ancient modernism, it rises to a level that melds tragedy and comedy.

The searing truths that run through Harris’ themes confound to a new clarity, especially if you see yourself as color blind and gender blind. Harris gouges out our assumptions and parades them in front of our unwillingness to perceive our hidden feelings about race, sex and power, teasing us in the process. By gaming his audience, Harris is all about stopping the games and taking off the masks. And he achieves this through the gyrations of his characters, three mixed-race couples who have sought therapy for their anhedonism (inability to feel pleasure-a symptom of depression and other ailments) with their partners.

The three couples sign up for “Antebelleum Sexual Performance Therapy” in order to expurgate their conflicts concerning race and sex that are ancient unconscious impulses or lesions borne from centuries of oppression in America from before the Civil War. It is an oppression that is in “black” and “white” unconsciousness that transcends skin color because the current society has historical remnants of the degradation of the “peculiar institution” which deformed the psyches of both masters and their slaves, the oppressors and the oppressed. Each couple suffers from these hidden twisted notions that they have ingested from living in American society. It has impacted them and they want a release from their suffering which manifests as alienation from their long-term partners.

This is a spoiler alert!

Joaquina Kalukango, Paul Alexander Nolan in ‘Slave Play,’ by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (Matthew Murphy)

Only, you don’t know that at first. Indeed, initially as the play opens, we believe we are watching a scene from the antebellum South involving the abuses of the master slave relationships via sexual sadomasochism. With these scenes highlighting the sexual “play” of the marriage partners, Harris hits us between the eyes and in the core of our presumptions in the hope of laying bare the psycho-sexual racial myths that lurk in our souls.

Thus, everpresent in the scenic design by Clint Ramos is the plantation mentality: the desire to oppress and degrade employing the vehicles of sex. Using mirrors Ramos reflects the white southern archetype of the white antebellum plantation of Master MacGregor’s mansion that encircles the proscenium. Throughout most of the production, the projection of the white plantation remains in the background, symbolizing that we may think we have been released from our history, but it resides just below the surface of consciousness in our relationships and especially in our relationships with members of another race concerning issues of true intimacy and honesty.

It is in this plantation setting that the characters dig in to expose their sadomasochistic impulses from a racist past that they have unconsciously internalized and must expiate to heal their marriage relationships. Harris humorously twits the audience’s assumptions about black sexual prowess and sensuality in the opening scene with each mixed race couple as they play out their fantasies to free themselves of the bondages that hamper reaching a satisfying closeness with their partners.

Gary (Ato Blankson-Wood) and Dustin (James Cusati-Moyer) portray the gay couple who cannot please each other. They engage in the fantasy of master/slave verbal abuse donning fictional characters, Dustin as an indentured servant and Gary as a slave who has been put in charge of him. Through the play acting, Gary reaches fulfillment but in his response to this, he upsets Dustin. There is only a partial breakthrough, tenuous at best. They have not exorcised the notions that harm them.

(L to R): James Cusati-Moyer and Ato Blankson-Wood in ‘Slave Play,’ written by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Phillip (Sullivan Jones) and Alana (Annie McNamara) portray a married couple who cannot achieve a hot intimacy until they enact their antebellum sex play. In their fantasy Alana is Master MacGregor’s wife and Phillip is her house slave who does what she wants. What pleases her is to take over the masculine role while he takes on the feminine role during a sexual encounter, something which makes her freer for intimacy with her partner. However, they too have issues because of Phillip’s race identity problems which he is loathe to admit and which to him are invisible.

The couple Kaneisha (Joaquina Kalukango) and Jim (Paul Alexander Nolan do not progress on this fourth day of the sexual fantastic. Jim finds the therapy ridiculous and demeaning. Ironically, it is Kaneisha who has engineered the roles and takes the lead in their improvisation. She portrays the slave and Jim (who has a British colonial accent-another irony) is the overseer who commands her unjustly, then sexually uses her as she uses him. But Jim finds her fantasy an impossibility and will not subject himself to it. Is this not a case of subliminal control and domination over his wife Kaneisha?

With each of the couples’ fantasies, there are strong elements of sadomasochism which are supposedly exorcised in the service of removing blocking psychic layers that impede the couples’ pleasure with each other. Unfortunately, Jim has stopped the process for all the couples. A condition of the therapy they have all agreed to is that if one cannot continue, all must not continue. When the couples meet to discuss and analyze what they felt during their fantastic sexual exploits exposing their sub rosa “plantation” mentality, the conflict is on. And Harris’s characterizations continue on a profound and humorous track as problems arise. Each couple ends up confronting their partner with results that are both humorous and poignant.

At this juncture social scientists and therapy guides Patricia (Irene Sofia Lucio) and Tea (Chalia La Tour) attempt to analyze and reaffirm their subjects’ positive changes as a result of the antebellum sexual play therapy. That the researchers do this in a controlled, manipulative way is an irony considering that all seek freedom from their internalized racial oppressions (the predator/prey elements of human behavior). Harris sardonically reveals these individuals, including the scientists, may be duping themselves into believing they’re getting closer to a “clear,” when what they seek cannot be achieved in a week-long process, regardless of how extreme the interventions. Perhaps, what has been internalized must be overthrown with individual introspection on the part of both partners after a long period of time. There is no quick fix except sustained love, growth, patience, understanding and the will to be close which eventually, through loving practice, will manifest. Maybe.

Annie McNamara and Sullivan Jones in ‘Slave Play,’ written by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara (Matthew Murphy)

The “liberal” posture which infects the “white” characters who are coupled up with their “darker” equally infected counterparts Harris explodes by the play’s end, as he disintegrates the notion that racism’s complexities may be dealt with through extreme interventions and quickie therapies. Especially for couple Kaneisha and Jim there has been a break through in their relationship at great cost to Jim who upon facing himself, dislikes what he perceives himself to be. Whether they continue together after this turning point doesn’t matter. Each have understood a soul revelation and will never be the same again.

Harris’ Slave Play instructs us about our perceptions, our attitudes and our willingness to go to that place that is uncomfortable to shed the pretense and stop pandering to faux racial equanimity and justice. That is why the curtain mirror that reflects the audience’s faces effected by Clint Ramos’s superb scenic design is a clever touch in keeping with Harris’ themes. The more visible reflections are for the audience members who are down front in the expensive seats.

Shouldn’t we examine our own proclivities and assumptions about sex, race and power dynamics? Or should we just ignore that there is a confluence of currents roiling in the subterranean waters of our souls about race? How do we overthrow our past and live freely without internalized cultural oppressions: misogyny, paternalism, institutional racism, body objectification, appearance fascism, sexism, chauvinism, reverse racism and impulses of white supremacy which move along a continuum from faint to furious? All of these oppressions impact our intimacy with ourselves and others, whether we are in mixed race relationships or not. Harris suggest we investigate these tantalizing questions which are not for the faint of heart.

As Americans steeped in a social history of racial power dynamics that continue today, though many are loathe to admit it, one cannot view this play as a light observer. To have the themes resonate, one should follow the characters to the most profound levels and then consider the myths, the conceptualizations about being black, white and gradations of both culturally. One must see with new eyes what has not been seen before at this crucial time when leaders speak to and embrace racist hate groups (KKK, Neo Nazis, etc.) curry favor with the likes of David Duke and Richard Spencer, and give political advisors like Steven Miller great power and moment over US Immigration policy with the precise intent to discriminate, promote fear and abuse for political purposes.

(On Ground L to R): Ato Blankson-Wood, James Cusati-Moyer, Sullivan Jones, Annie McNamara, Joaquina Kalukango, Paul Alexander Nolan. (In red boxes L to R): Irene Sofia Lucio and Chalia La Tour, ‘Slave Play,’ directed by Robert O’Hara, written by Jeremy O. Harris (Matthew Murphy)

Harris intends to shock us into a dialogue to confront our own assumptions on whatever level we can, so we might grow as Americans who recognize their rich yet horrific social, political and cultural history. As Harris’ characters recognize they are stymied and self-harmed by their own misconceptions, depressions and failures to deal with the historical, ancestral folkways and noxious human behaviors they’ve internalized, at least they attempt to overthrow them. Shouldn’t we, Harris suggests? But are we up for this? We should be! Look at the gun shootings at synagogues and black churches.

Until there are conversations about such controversial topics as Slave Play raises, the country’s divisiveness may be exploited by pernicious leaders and malevolent foreign intelligence services who foment racial hatreds to satisfy their own personal agendas. Our culture’s current divides are toxic. To mitigate them requires a complexity of understanding and introspection on a personal level. Harris indicates dealing with this on an interracial, mixed couple level may be the way to get there if there is love, patience, understanding and will. The issues are hyper complex and are not adequately answered by quick fixes and exotic hyperbolic interventions which themselves represent the internalized predator/prey, oppressor/oppressed remnants of racism.

The ensemble is wonderful and acts seamlessly together with a comfortability at behaviors which appear impossibly raw. The therapy session is particularly acute, funny, authentic and smashing. All the actors are standouts as is required with such an amazing play. Kudos to the director who shepherded them. Each couple ends up confronting their partner with results that are both humorous and poignant.

The design team also shines: Dede Ayite (costume design) Jiyoun Chang (lighting design) Lindsay Jones (sound design & original music) Cookie Jordan (hair & wig design). Conceived at New York Theatre Workshop where it ran in from November 2018 to January 2019, Slave Play has come to Broadway where it is provoking consternation, confusion and revelation. It runs with no intermission until 19 January. There are too many reasons why you should see this play if you are an American, and especially if you have a bit of residual racism within and are adult enough to laugh at yourself. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.