Blog Archives

‘Irishtown,’ a Rip-Roaring Farce Starring Kate Burton

Irishtown

In the hilarious, briskly paced Irishtown, written by Ciara Elizabeth Smyth, and directed for maximum laughs by Nicola Murphy Dubey, the audience is treated to the antics of the successful Dublin-based theatre company, Irishtown Plasyers, as they prepare for their upcoming Broadway opening. According to director Nicola Murphy Dubey, the play “deals with the commodification of culture, consent and the growing pains that come with change.”

Irishhtown is also a send up of theatre-making and how “political correctness” constrains it, as it satirizes the sexual relationships that occur without restraint, in spite of it. This LOL production twits itself and raises some vital questions about theater processes. Presented as a world premiere at Irish Repertory Theatre, Irishtown runs until May 25, 2025. Because it is that good, and a must-see, it should receive an extension.

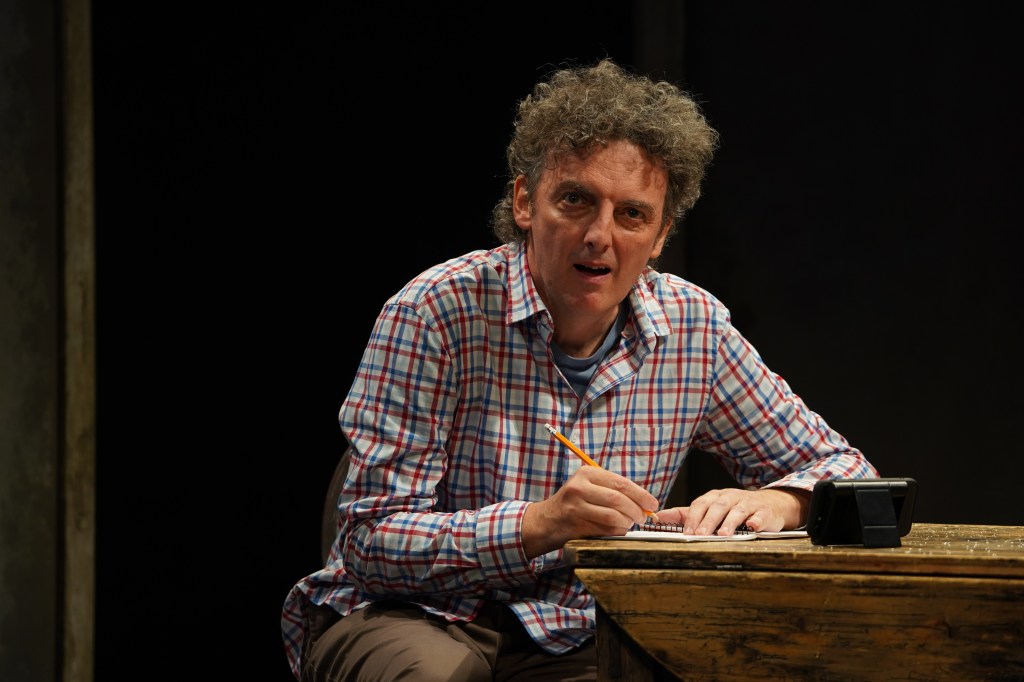

The luminous Kate Burton heads up the cast

Tony and Emmy-nominated Kate Burton heads up the cast as Constance. Burton is luminous and funny as the understated diva, who has years of experience and knows the inside gossip about the play’s director, Poppy (the excellent Angela Reed). Apparently, Poppy was banned from the Royal Shakespeare Company for untoward sexual behavior with actors. Burton, who is smashing throughout, has some of the funniest lines which she delivers in a spot-on, authentic, full throttle performance. She is particularly riotous when Constance takes umbrage with Poppy, who in one instance, addresses the cast as “lads,” trying to corral her actors to “be quiet” and return to the business of writing a play.

What? Since when do actors write their own play days before their New York City debut? Since they have no choice but to soldier on and just do it.

The Irishtown Players become upended by roiling undercurrents among the cast, the playwright, and director. Sexual liaisons have formed. Political correctness didn’t stop the nervous, stressed-out playwright Aisling (the versatile Brenda Meaney), from sexually partnering up with beautiful lead actress Síofra (the excellent Saoirse-Monica Jackson). We learn about this intrigue when Síofra guiltily defends her relationship with the playwright, bragging to Constance about her acting chops. As the actor with the most experience about how these “things” work in the industry, Constance ironically assures Síofra that she obviously is a good actress and was selected for that reason alone and not for her willingness to have an affair with Aisling.

Eventually, the truth clarifies and the situation worsens

Eventually, the whole truth clarifies. The rehearsals become prickly as the actors discuss whether Aisling’s play needs rewrites, something which Quin (the fine Kevin Oliver Lynch), encourages, especially after Aisling says the play’s setting is Hertfordshire. As the tensions increase between Quinn and Aisling over the incongruities of how an Irish play can take place in England, Constance stumbles upon another sexual intrigue when no one is supposed to be in the rehearsal room. Constance witnesses Síofra’s “acting chops,” as she lustily makes out with Poppy. This unwanted complication of Síofra cheating on Aisling eventually explodes into an imbroglio. To save face from Síofra’s betrayal and remove herself from the cast’s issues with the play’s questionable “Irishness,” Aisling quits.

Enraged, the playwright tells Síofra to find other living arrangements. Then, she tells the cast and director she is pulling the play from the performance schedule. This is an acute problem because the producers expect the play to go on in two weeks. The company’s hotel accommodation has been arranged, and they are scheduled to leave on their flight to New York City in one week. They’re screwed. Aisling is not receptive to apologies.

What is in a typical Irish play: dead babies? incest? ghosts?

Ingeniously, the actors try to solve the problem of performing no play by writing their own. Meanwhile, Poppy answers phone calls from American producer McCabe (voice over by Roger Clark). Poppy cheerily strings along McCabe, affirming that Aisling’s play rehearsals are going well. Play? With “stream of consciousness” discussions and a white board to write down their ideas, they attempt to create a play to substitute for Aisling’s, a pure, Irish play, based on all the elements found in Irish plays from time immemorial to the present. As a playwright twitting herself about her own play, Smyth’s concept is riotous.

The actors discover writing an Irish play is easier said than done. They are not playwrights. Regardless of how exceptional a playwright may be, it’s impossible to write a winning play in two days. And there’s another conundrum. Typical Irish plays have no happy endings. Unfortunately, the producers like Aisling’s play because it has a happy ending. What to do?

Perfect Irish storylines

In some of the most hilarious dialogue and direction of the play, we enjoy how Constance, Síofra and Quin devise their “perfect Irish storylines,” beginning with initial stock characters and dialogue, adding costumes and props taken from the back room. Their three attempts allude to other plays they’ve done. One hysterical attempt uses the flour scene from Dancing at Lughnasa. Each attempt turns into funny scenes that are near parodies of moments in the plays referenced. However, they fail because in one particular aspect, their plots touch upon the subject of Aisling’s play. This could result in an accusation of plagiarism. But without a play, they will have to renege on the contract they signed, leaving them liable to refund the advance of $250,000.

As their problems augment, the wild-eyed Aisling returns to attempt violence and revenge. During the chaotic upheaval, a mystery becomes exposed that explains the antipathy and rivalry between Quin and Aisling. The revelation is ironic, and surprising with an exceptional twist.

Irishtown is not to be missed

Irishtown is a breath of fresh air with laughs galore. It reveals the other side of theater, and shows how producing original, new work is “darn difficult,” especially when commercial risks must be borne with a grin and a grimace. As director Nicola Murphy Dubey suggests, “Creative processes can be fragile spaces.” With humor the playwright champions this concept throughout her funny, dark, ironic comedy that also is profound.

Kudos to the cracker-jack ensemble work of the actors. Praise goes to the creatives Colm McNally (scenic & lighting design), Orla Long (costume design), Caroline Eng (sound design).

Irishtown runs 90 minutes with no intermission at Irish Repertory Theatre, 132 West 22nd St. It closes May 25, 2025. https://irishrep.org/tickets/

‘Aristocrats,’ Irish Repertory Theatre, Review

Dysfunction and decay are principle themes in Brian Friel’s Chekovian Aristocrats, a two-act drama about a once upper middle class family in precipitous decline in the fictional village of Ballybeg, County Donegal, Ireland. Currently at the Irish Repertory Theatre as the second offering in the Friel Project, the intricate and fine production is directed by Charlotte Moore and stars a top-notch cast who deliver Friel’s themes with a punch.

Two members of the O’Donnell family, headed up by the autocratic and dictatorial father, former District Justice O’Donnell (Colin Lane),, who remains offstage until a strategic moment brings him on, have arrived at the once majestic Ballybeg Hall. They are there to celebrate the wedding of Claire (Meg Hennessy), the youngest of the four children, who still lives with her sister Judith (Danielle Ryan), the caretaker of the estate. Well into the play, Ryan’s Judith reveals the drudgery of her responsibilities caring for her sickly father and her depressive sister Meg, as well as managing the estate and the chores of the Big House.

At the top of the play, we meet the grown children who live abroad and arrive from London and Germany. These include Alice (Sarah Street), her husband Eamon (Tim Ruddy), and the O’Donnell brother Casimir (Tom Holcomb). As Friel acquaints us with his characters, we discover Eamon, who once lived in the village, claims he knows more about Balleybeg Hall from his grandmother, who was a maid servant to the O’Donnells. Also present is Willie Diver (Shane McNaughton), who is attentive to Judith as he helps her around the estate and farms and/or rents out the lands to the locals. Initially, we watch as Willie organizes a monitor through which Justice O’Donnell can speak and ask for Judith to attend to him.

By degrees, through the character device of the researcher, Tom Huffnung (Roger Dominic Casey), and especially the ironic comments of Eamon, Friel discloses who these “aristocrats” of Ireland are. First, they were the upper class with land, who once dominated because the English protestant faction empowered them to do their bidding. The irony is that over the years, they have devolved and have imploded themselves. The sub rosa implication is that the seduction of the English, to give these Catholic Irish power, has led to their own emotional and material self-destruction.

The father, the last of the dying breed of “gentlemen,” like his forebears, took on the cruel, patriarchal attitude of the English. Raising his family in fear and oppression, and indirectly causing his wife’s suicide, he has deteriorated after strokes. We learn this by degrees, as Friel catches us unaware, except for the title of the play, by revealing the characters to be on equal class footing at the play’s outset. We learn the irony of the great “fallen.” The past distinction between the “superior” O’Donnell’s of the Hall, and the rest of the village peasantry, who referred to them as “quality,” (Eamon’s grandmother’s definition), has faded and is only kept alive in the imagination of a few.

Throughout, Claire’s music can be heard in the background as Alice and Casimir converse with Huffnung, whose research topic is about the impact of the Catholic Emancipation laws on the “ascendant Roman Catholic ruling class and on the native peasant tradition.” In other words Huffnung has come to Ballybeg Hall to research the aristocratic O’Donnells and discover the political, economic and social impact they have had on the villagers.

Interestingly, Eamon sums it up to Huffnung when he ironically answers the question as an insider who knows the Hall and what it is like being married to Alice, one of the former “ruling class.” Alice and her sister Judith were repeatedly sent away from home for their schooling. Alice marries Eamon who, caught up in the Civil Rights action against the English Protestants, loses his job in Ireland and eventually works for the English government in London. Alone most of the day, Alice has become an unhappy, isolated alcoholic. Eamon, whose irony wavers between obvious bitterness and humor tells Huffnung that the O’Donnells have had little or no impact on the local or “native peasants,” of which he numbers himself as one of the classless villagers.

Indeed, noting the shabbiness of the Hall and the problems of the family members, we see the pretension of superiority has long gone. All of them face emotional challenges and need rehabilitation from their oppressive upbringing under their father, Justice O’Donnell who seems to have be a tyrant and unloving bully. We note this from his rants over the monitor and Casimir’s response to his father’s imperious voice.

Judith contributed to causing her father’s first stroke having a baby out of wedlock with a reporter, after joining the Civil Rights fight of the Catholics against the British Protestants. Forbidden to raise her child at home, which would bring shame to the family, she was forced to give him up for adoption; he is in an orphanage. Over the monitor in a senile rant we hear the bed ridden O’Donnell, refer to her as a traitor. Thus, we imagine the daily abuse she faces having to care for her father’s most basic needs, while he excoriates her.

Meg is a depressive on medication who helps around the house, plays classical piano, and plans for her marriage to a man twice her age in the village, a further step down in class status. Desperate to leave, she selects escape with this much older man who has four children. She enjoys teaching piano to them.

Casimir is an individual broken by his father’s tyranny and cruelty. Holcomb’s portrayal of the quirky, strange Casimir is excellent, throughout, but particularly shines when he reveals to Eamon, how Justice O’Donnell’s attitude shattered him. The Justice’s cruel judgments about his only son, are revealed by Casimir toward the conclusion of the play. Ironically, Casimir politely attempts to uplift the family history to Casey’s clear-eyed Huffnung who, tipped off by Eamon, fact checks the details and realizes that Casimir exaggerates with a flourish. Additionally, most of what Casimir shares about his own life is suspect as well, and used to appear “normal,” though he may be gay.

Thus, as Friel unravels the truth about the family, largely through Eamon, we come to realize the term “aristocratic” is a misnomer when applied to them. The noblesse oblige, if it once existed, has declined to mere show. As Casimir attempts to enthrall Huffnung with the celebrated guests who visited the Hall (i.e. Chesterton, Yeats, Hopkins), his claims by the conclusion are empty. In turn Huffnung’s research seems ironic in chronicling the decline of an aristocracy that has self-destructed because it remained isolated and assumed a privileged air, rather than become integrated with the warmth and care of the local Irish Catholics.

The brilliance of Friel’s work and the beautiful direction by Charlotte Moore and work of the ensemble shines in how the gradual expose of this family is accomplished. As the ironies clarify the situation, Friel’s themes indicate how the oppressor class inculcated those who would stoop to their bidding to maintain a destructive power structure which eventually led to their own demise. Of course, Eamon, who is bitter about this, also finds the “aristocracy” enchanting. He wants them to maintain the Great House and not let it go to the “lower class” thugs who will destroy it further, though it is in disrepair and too costly to keep up.

The class subversion is subtle and hidden. What appears to be “emancipation” perhaps isn’t, but is further ruination. How Moore and the creatives reveal this key point is vitally effected.

Thanks to Charlie Corcoran’s scenic design, we note the three levels of the Big House’s interior and exterior where most of the action takes place. David Toser’s costume design is period appropriate. Ryan Rumery & M. Florian Staab’s sound design is adequate. The original music is superb along with Michael Gottlieb’s lighting design. Accordingly, Justice O’Donnell’s entrance is impactful.

This second offering of the Friel Project is a must see. Aristocrats is two acts with one fifteen minute intermission. For tickets go to the Box Office of the Irish Repertory Theatre on 22nd Street between 6th and 7th. Or go online https://irishrep.org/show/2023-2024-season/aristocrats-2/

‘Love Letters,’ by A.R. Gurney, Starring Matthew Broderick & Laura Benanti, The Conclusion of Irish Rep’s Letters Series.

The intimacy of listening to the voices of individuals’ emotional grist, concern and vibrance through letters written to a secret confidante is delicious and stirring in this time of 140 characters where “brevity is often not the soul of wit.” Irish Repertory Theatre’s “Letters Series” portrays the profound, intimate relationship between two individuals not “visible” to the naked eye of friends and relatives, and sometimes not gleaned by the characters themselves until it is too late.

The first series, now ended, starred Melissa Errico and David Staller in Jerome Kilty’s play Dear Liar. Kilty reconfigured his play from the decades-long epistolary relationship between George Bernard Shaw and the actress, Mrs. Patrick Campbell. The second part of the series highlights Matthew Broderick and Laura Benanti in A.R. Gurney’s (Pulitzer Prize finalist for Drama) Love Letters, directed by Ciarán O’Reilly. The staged reading of the drama with prodigious comedic elements runs with one intermission on the Irish Repertory Theatre’s Francis J. Greenburger Mainstage and concludes on the 9th of June.

Gurney’s two-act play explores the arc of the decades long relationship between friends and eventual lovers, Andrew Makepeace Ladd III (played by the inimitable Matthew Broderick) and Melissa Gardner (Laura Benanti is fresh, witty, humorous). These individuals write letters to each other over a span of decades (1937-1985), beginning in the second grade when Mrs. Gardner sends Andy an invitation to Melissa’s birthday party, and Andy responds to Melissa accepting the invitation.

From then on the the individuals share a profound written correspondence, though Melissa tells Andy to stop writing to her initially and at various times during their lives. At first, it is because she prefers pictures to words. Afterwards, it is because the words are so heartfelt and searingly directed to her, they are breathtaking to process and conflict with her estimation of Andy when they meet in person.

Oftentimes, reverse psychology is at work in Gurney’s pla,y where subtext and undercurrent in the dialogue between the characters takes precedence. The characters are confessional, argumentative, challenging, and interested in each other as friends, though there is always the sense that their concern for each other, authenticity and the bond formed through words reveal theirs is not an ordinary friendship, but one of the most sincere, transcendent and special that love might bring, even though it is not formalized in marriage.

Gurney intimates the possibility that their feelings have the potential for intimacy with their child-like innocent abandon (in 2nd grade), when Andy asks if Melissa will be his valentine, and Melissa agrees that she will, if she doesn’t have to kiss Andy. The verbal affection continues when we learn that Andy repeatedly asks Melissa to marry him. She gets him to stop, by telling him she will go with him to get the milk and cookies for the class, if he stops proposing to her. When Melissa employs her skills drawing, which she enjoys doing, she draws pictures of them without their bathing suits on, asks if he knows which one he is, then importunes him not to tell anyone about her drawing. She concludes by telling him she loves him.

This thrust and parry structurally mirrors the pattern of their relationship. Andy initiates his desire to be close to her. Melissa avoids responding, then eventually comes around to agree with him. Then, something intervenes and prevents them from actually becoming boyfriend and girlfriend or partners. When they finally try to extend their relationship beyond the intimacy of their writings and meet “live” for a weekend at the Harvard/Yale game, their date, including sexual coupling explodes in their faces. There is more “aliveness” in their writing, than in their ability to regain the soulfulness of their correspondence face to face. It will take other circumstances to transpire in Act II before any meaningful physical coupling occurs.

Ironically, despite their union and knowledge of each other that they’ve gleaned over the years and expressed in writing in the comfort of their surroundings, confronting each other in their “real” identities is problematic. Or perhaps the mental/spiritual connection through letters is their real identity.

Their written consciousness is a mystery. As Andy attempts to rationalize why their intimacy backfired when they met in person, Melissa blames the letter writing and suggests Andy phone her. However, this doesn’t work out and Melissa becomes infuriated with Andy when she hears he is writing letters to someone else, because he has fallen in love with the words coming out of his soul. Through their correspondence, he has discovered that he is compelled to write letters to “someone” to better know himself.

Andy’s love of writing and expressing himself to Melissa who listens and responds to him throughout elementary school, high school, college, the Navy and their travel to various places on the globe manifests in his career as a lawyer. Melissa’s drawing talents, that she initially felt comfortable to share with Andy, burgeon into a full-blown career as a professional artist who exhibits in New York City. Their epistolary relationship reveals a love, honesty and encouragement unlike that found in their other relationships. However, whether Melissa can bear continuing the writing when she dislikes it and believes it is keeping them apart physically gives both of them pause. Andy suggests that he hopes they can work it out and keep writing.

The suspense whether or not they will ever “get together” in a lasting marriage carries into Act II. However, by then, both end up with other individuals. Again, something intervenes to keep their love distant and unfulfilled. Every time Andy asks if Melissa is OK, she provides a “stiff up lip” response that she is “fine,” though we know she is not. Likewise, Andy never goes beyond his father’s folkways (family country, himself) which Melissa proclaimed was stifling him when they were teenagers. Following his father’s dictum, Andy fulfills his obligations to his family, country and himself sacrificially.

Though he and Melissa fulfill their love which blossoms, unlike that which they experience with others, Andy eventually falls back on his father’s belief, uplifting the traditional sacrifice of his own happiness. His choice to put his own desires last has disastrous consequences for both of them, only realized too late.

Broderick and Benanti bring their own unique talents and personalities portraying Andy and Melissa. Shepherded by O’Reilly, they strike the right tonal notes and pacing to engage us. We become involved in these two individuals to care about them and take the journey of life through elementary school, private high schools, college, careers and marriages to other individuals, all the while reading the sub rosa signs that they mean so much to each other and missed their destiny by never marrying and having children. Thus, the tragedy of the ending is all the more greater.

Throughout, Gurney’s clever dialogue, wit and fervor crafts individuals that Broderick and Benanti solidly inhabit to make them believable to us. From halting, shy children who are obligated by their parents to write birthday thank yous to hardened adults who have veered off their truth and empowerment, we accept all, even the abrupt conclusion which belies their soulful devastation leaving Andy to pick up the pieces.

The importance of this two-hander’s themes about human nature, love, cultural influences and the power of intimacy in correspondence lies in Gurney’s characters as they age. Andy and Melissa perceive each other’s identities and ethos first as innocent, frank children. As the corrupted environments harden them, they push each other away. The irony is that they are the only individuals that truly matter to each other in their lives as adults.

That Gurney has selected individuals who are upper middle class and are white, Protestant and privileged is telling. To a large extent it is their background folkways and traditions that Melissa rebels against and Andy adheres to that walls them off from each other. In their heart of hearts they are soul mates which Andy expresses and Melissa acknowledges, though they are incapable of taking the plunge to overthrow the strictures that bind them.

That Gurney in his notes wisely instructs the minimalism of sets (a table and two chairs facing out to the audience), simple lighting and reduced theatricality enhances the dialogue and focuses our attention on realizing the humanity of these two lovers traveling their destiny together in written words.

Broderick portrays Andy with unaffecting humor which allows Gurney’s ironies to be revealed all the more quickly. Benanti is sardonic and edgy with rebellion that is balanced just enough so as not to be curdling or understated. Both hit the mark to tease out their characters with a poignancy and grace that reminds us that love requited but not fulfilled is its own tragedy. In this staged reading we understand Gurney’s emphasis on the power of expression in a truthful exploration of relationships and love under the guidance and wisdom of director Ciarán O’Reilly.

For tickets to this fine staged reading with superb actors see below.

‘The Smuggler,’ A Thriller in Rhyme at Irish Repertory Theatre

In an energetic, boisterous performance delivered with a fever pitch that doesn’t quit or pause with quieter notes, Michael Mellamphy’s Tim Finnegan spills out The Smuggler, a story about how, as a naturalized citizen from Ireland, he was forced into a black-hearted situation he couldn’t refuse. In his delivery Mellamphy is like a high-speed train barreling down the track on a joy ride that threatens catastrophe at each turn in the journey, as customers and audience members alike are drawn in with his humor, excitement and storytelling verve, unfolding in rhyming couplets, that at times are insecure and slant. Written by Ronán Noone, himself an Irish-American immigrant from Galway, and directed by Conor Bagley, The Smuggler runs a slim 80 minutes at Irish Repertory Theatre in the W. Scott McLucas Studio Theatre. It has been extended until March 12.

At the heart of The Smuggler the protagonist (a con artist) attempts to get over with his charm and engagement to elicit audience sympathy. He seeks this as he tells about his plight to make a way for himself and his family in a culture that is the antithesis of welcoming and helpful to those “down on their luck.” When he’s fired from his job as a barman in Amity, Massachusetts, every door appears to shut in Finnegan’s face. Understanding the dark irony that America is portrayed as the land of “opportunity” in the alluring myth (the streets are paved with gold) told to strangers from other shores to entice them to leave their home country to provide cheap labor whether legal or illegal, he is caught in a morass of financial wrack and ruin of his own making.

Not only does Finnegan enjoy “a bit of drink” (an explanation for the selection of his job as barman) he appears not to be too swift in forward planning financially with his wife. Everything is a surprise that happens to them, not that they are responsible for selecting actions that leave them hanging off a cliff.

Many immigrants face hellish experiences, exploited by craven, greedy bosses, forced to live in overcrowded quarters, the pawns of merciless overlords wherever they turn. We have only to read about the history of America’s labor movement or Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers, or superlative, recent, non-fiction works (Tomato) to understand the desperation that immigrants go through, first to leave their countries, and then to attempt to “make it,” continuing the hell of the past in the present new “home.”

Thus, life moves from wheel to woe for those like Finnegan, who strike out to start a family, make missteps with bad choices, then fall on hard times. Finnegan and his wife live in a rental, that is no more than a shack with non-functioning plumbing. It is owned by a slumlord, a sleazy landlord who refuses to fix much of anything. As Finnegan unravels his dire circumstances with heavy poetic description, we identify with the immigrant experience, recognizing that the uniform abuse by those happy to mistreat and exploit the cheap labor of aliens and immigrants, is all too familiar.

What makes Finnegan’s experience a bit more interesting is how at each turn, being backed into a corner, by his boss, the landlord and the wife, he seeks a way to improve his family circumstances by “any” means necessary. Of course there’s the rub. “Any” reverts to lowering standards and morals he may have as a human being, as he turns to a life of theft and exploitation of other aliens and immigrants, he works with at his construction job.

Noone characterizes Finnegan during his monologue confessional with an emphasis on masculine bravado, fearlessness (especially when he confronts a menacing, “man-eating” rat) and chivalry in saving his wife and child from poverty, destitution and want. The heroic portrait is right out of “Captain America,” part of the glorious beauty of the American Dream of success, which lifts up the “heroic struggle” and vitiates the criminality, exploitation and violence that under-girds it. A good scam artist, Finnegan seductively blinds the audience to see things “his way,” so that they accept his justifications for his choices. His “bravery” and good will serves him like a magician’s prestidigitation at redirecting our understanding away from his conning nature.

Because his storytelling appears authentic and forthright, we gloss over his lack of accountability and responsibility in taking the low road toward crime, which he admits with (feigned?) abashment. Though he selects the exploitative way that harms and abuses others, we look at his efforts to succeed materially, not the dark side which he uses to get his “ill-gotten gains.” Finnegan’s “happy-go-lucky” attitude indicates that he knows the difference, but makes excuses for his behavior: “what else could he do?” The conclusion reinforces his triumph at “getting over.” The knock at the door, which we may anticipate brings recompense and punishment, never comes. Instead, the knock at the door brings a blessing. (There is no spoiler alert. You’ll just have to see The Smuggler to understand the symbolism of the knock on the door of the bar he was fired from, that his life of crime enabled him to buy back later on.)

Thus, Finnegan’s ultimate success as an Irish American is in how well he has gotten over, gotten the loot, made a beautiful material life for himself and his family, so they can “live happily ever after.” That there is some danger that lurks behind the triumphant Finnegan brand is smothered over by his intrepid nature and gumption to “just do it!” His is a male Cinderella story of achieving wealth. His macho actions to sacrifice for “the wife and family” actually reference the Trumps and Putins of the world and ridicule those who amass little monetarily, but scrape enough to get by, living in humility, honesty and decency. With boldness, his bravado encourages criminality and uplifts the fact that the law (represented by his adulterous cop brother-m-law) is capricious, unequally meted out and dysfunctional. Dali Lama, an unqualified loser, you have no place in America with your muted, unmaterialistic, nice-guy values

Rather than to evolve with hard work, sobriety, education and an ethos that undermines the exploitation of the abusive system that enslaves its workers and has converted Finnegan into a criminal, Finnegan jumps right in and embraces the “opportunity” to be at the top of the heap as “King Rat.” The symbolism of his killing the rat “guarding” a safe in the basement, whose contents he takes, is quite apparent. Ultimately, if justice ever knocks at Finnegan’s door, then he will have effected his own final self-destruction. Maybe! However, with his glib rhyming he proves to himself that there is nothing he can’t accomplish to become a success and be the type of “American” that extols scammers, con artists, schemers and material wealth, regardless of the soul damage and foulness created in the process. If he needs to, Finnegan has proven he’s a survivor. He can even get over in prison, if need be.

Clearly, Finnegan is smuggling more than a few ideas past the audience to justify his successful existence as proof of his greatness. The irony of themes and the well-written characterization acted by by Mellamphy and enhanced by the director’s vision is one more blow to smash the myths we may use to live by, as we dupe ourselves about America as a great nation. Clearly, it is fabulous for billionaires. For the immigrants who exploit and shred each other as the bosses divide and conquer them and us, it’s another America entirely. That Finnegan’s survival is cast in monetary terms aided and abetted to by his wife is his chief tragedy. But “what else can he do?” It’s the “land of the free and the home of the brave,” sung at every sports event nationwide.

Thanks to the creative team’s execution of set design which is just superb (Ann Beyersdorfer) atmospheric lighting design (Michael O’Connor) and sound design and original music (Liam Bellman-Sharpe). The production is first rate, if unsettling, as it leaves us with profound questions about how much we accept our foundational culture’s lies as truths.

For tickets to The Smuggler at Irish Repertory Theatre in the W. Scott McLucas Studio Theatre, go to their website https://irishrep.org/show/2022-2023-season/the-smuggler-2/

Ronán Noone

‘Chester Bailey’ Starring Reed Birney and Ephraim Birney, a Must-See

Joseph Dougherty’s Chester Bailey is a mind-bending drama that tests our understanding of reality, as that which we apprehend with our senses. Taken to its extreme form, those whose senses have been deprived cannot know what reality is and must rely on others to interpret “the reality” of what is around them. However, what happens if they refuse to accept any interpretations and come up with their own? Who gets to interpret what reality is, if the interpretation is repugnant and an encouragement toward self-destruction?

These delicious questions lead to the conundrum that Dr. Philip Cotton (Reed Birney), must resolve as he treats his patient Chester Bailey (Ephraim Birney), who is in a hospital on Long Island in 1945 during the winding down of WW II. Bailey was prevented from going to war by his parents who selfishly wanted to keep their son safe, a notion that Bailey tells us he agreed with so he didn’t rebel against their wishes and enlist.

However, Karma, Fate the Furies spin the family around and have fun with them, proving there is no escape from tragedy. Yet, if we throw caution to the winds and accept what comes, goodness may be around the corner. Perhaps Chester should have enlisted after all. His family and Bailey rue that he didn’t.

Bailey ends up in the psychiatric care of Dr. Philip Cotton after he experiences a traumatic accident at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. A psychotic worker attacks him with a blow torch putting out his eyes, slashing his ear, savaging his face and severing his hands. After defying death, Chester rehabilitates getting through unaccountable pain with the help of huge doses of morphine that foster his dislocation from reality to a place of comfort, and not only physical comfort.

In that haven, he constructs another reality where he believes that he lost his ear and eyesight, but the latter is returning because he sees a bright light that appears to be getting brighter. Furthermore, he “knows” he still has use of his hands and can pick up objects, all despite arguments with the doctors at the general hospital where he’s recovering, who tell him he has no eyes, no hands, one ear and his face is deformed. Indeed, Ephraim Birney’s portrayal of Chester’s believable reconstruction of a world of peace and beauty, where he is becoming whole is sensational. And Birney’s development of Chester’s obstinance and obstruction of anyone who attempts to wrangle his fantasy from him is beyond superb.

Though Chester tells us he receives visits from his father, who tries to encourage him despite his growing alcoholism, his mother refuses to see him. Ephraim Birney’s narration is riveting. Through it we intuit that his mother is overwhelmed by guilt. Smacked by Karma at her selfish attempt to save her son from dying, while other mothers lost their sons, she refuses to visit him and is bedridden with severe depression.

Meanwhile, Birney’s Chester is enthusiastic about seeing shapes and shadows, feeling his fingers and picking up objects. The doctors deem him delusional. Because of Chester’s prognosis, they cannot release him back into society where he will only get worse. Instead, they transfer him to a psychiatric hospital, where he will receive therapy to perhaps encourage him back to the society’s consensus of reality. There he will be forced to accept his condition and receive help to achieve a purposeful life.

Parallel to Chester Bailey’s “delusion” is Dr. Philip Cotton’s response to Bailey. Steeped in partial delusions, we understand that Cotton bends reality toward his own perspective. We discover how both men are two different sides of the same coin from the top of the play, when Dougherty has each man in solo performance introduce themselves when Dr. Philip Cotton meets Chester for the first time in the Long Island psychiatric hospital.

From there time shifts in a flashback to the point before Chester’s accident in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Through an interlocking web of solo moments addressed to the audience, we discover who these men are and their approach toward their lives, which in actuality isn’t that much different.

Reed Birney is absolutely sensational in his quiet, unspooling of himself as Dr. Cotton who ironically is dislocated from his marriage when he works in Washington, D.C. Birney’s narration of events is engaging and smooth. Alternating with Chester, who discusses his life in parallel themes, Cotton tells us when he was in Washington, D.C. working, his wife had an affair. Its revelation explodes their marriage when he transfers to the Long Island hospital and moves to New York. In fear of discovery, her lover demands that she tell Cotton the truth. Cotton and his wife get a divorce.

Obtusely moving through his life, Birney’s Cotton doesn’t pick up the signs or even understand why and how his wife could betray him. Instead of learning from this emotional devastation to himself, their daughter and his former wife, he engages in an affair with Cora, his bosses’ wife and wraps himself in her to the point that she becomes his life. Indeed, he lives for the times they covertly meet in various, sleazy, hot pillow motels around the Island.

The beauty of his performance is Birney’s authenticity in portraying Cotton, whose serene and calm self-satisfaction covers up his own delusions about himself and his divorce which he accepts without seeking therapy before or after. His escapism into his affair with Cora conveniently runs him far away from self-analysis or introspection.

Additionally, Birney’s performance is magnificent in its subtly. Cotton manufactures his intent to help Chester Bailey “face” reality so Chester can “better” live his life and adjust to his deformities. In relaying his behavior with Bailey as he interacts with him and reveals his final kindness to him, we are duped by his laid-back good-natured care. Completely taken by his apparent concern for his patient and his romantic interpretations, we ignore why he bestows magnanimity on Chester at the play’s conclusion.

However if one considers the ramifications of what Birney’s Dr. Cotton does when he ignores the truth of what occurs in the hospital, Cotton’s behavior can also be interpreted as permissive and incredibly destructive. Nevertheless, Birney’s Cotton, who is deluded himself and swept up into going beyond his role as a professional, treats Bailey as he, himself, wishes to be treated.

Ironically, Cotton’s interpretation of Chester as an artist of the imagination absolves himself and Bailey of the truth, pushing away the results as if there are no consequences or probabilities of harm. Ignoring his own behavior in accepting Bailey’s behaviors and converting them into harmless obfuscations, he entraps them both in fantasy. Defining Bailey’s actions as self-mercy, Birney’s Cotton removes his own accountability from the situation and demeans Bailey by not challenging him to evolve beyond a “merciful” delusion. The question becomes how merciful is this delusion? And indeed, are delusions merciful?

Engaged and enthralled by the Ephraim and Reed Birney’s portrayals of these intricate and complicated characters, we, too, are swept up in the romance and artistry that Bailey weaves and Cotton accepts and encourages. So what if these flights of imagination have a dark underbelly that perhaps is dangerously dismissed?

We ask, if someone’s life is so physically decimated as Chester’s life is, then what is the harm of his imagining that the woman he saw selling paper and candy in a shop in Penn Station (the beautiful old station intimated with John Lee Beatty’s scenic design and Brian MacDevitt’s lighting design), has become a nurse who visits him? What is the harm if he imagines it is she who has sex with him in his hospital bed late at night and not someone else who has severe problems? He is in love with her, a person he fashions in his imagination. Isn’t that what love is? When we love, don’t we project onto others the beauty and artistry of ourselves? Isn’t that what Dr. Cotton does with Cora? Aren’t we in love with the product of our own imaginations?

Indeed. Of course, there is more to what Doughtery unravels in this rich, dynamically threaded philosophical, psychological work, beautifully shepherded by director Ron Lagomarsino and acted with perfection by father and son duo Reed Birney and Ephraim Birney. Chester Bailey asks so many questions and resolves none of them which makes for a great play that is profoundly rich with thematic gravitas that is resonant for our time.

The production is gobsmacking, helped by Toni-Leslie James’ costume design and Brendan Aanes’ sound design. Performances have been extended because they should be. This outstanding work is its New York Premiere at Irish Repertory Theatre. For tickets and times go to their website. You’ll be happy you saw this amazing, moving play. https://irishrep.org/

‘Belfast Girls,’ a Powerful, Shining Work at the Irish Repertory Theatre

The phenomenal Belfast Girls in its New York Premiere at Irish Repertory Theatre takes place in 1850 during Ireland’s “An Gorta Mor” (The Great Starvation) on the ship the Inchinnan. Five women who have struggled through the Great Famine are chosen to leave Ireland. The trip will take them to the colony of Australia to embark on a better life. With dreams and hopes, the women undergo a three month voyage and mentally prepare themselves for the desires of their heart. What they discover on their journey is a personal and historical truth that they must confront the moment they disembark.

With Nicola Murphy’s incisive direction, the effective and keenly crafted, functional design of women’s quarters below deck (Chika Shimizu) creates a sense of the confined space they endure. The superb cast transports the audience into the minds and hearts of the Belfast Girls, the most raucous, riotous and infamous of the women accepted into the Orphan Emigration Scheme. The Scheme established by Earl Henry Grey in the 1840s sent 4000 orphaned women from Ireland to Australia to relieve Ireland’s overcrowded workhouses and poorhouses from the ravages of the Great Famine.

Under the largesse of Grey’s Scheme we watch as five women from disparate Irish backgrounds bunk together on the Inchinnan and travel for three months down the coast of Africa and around Cape Horn to become “rich” farmers’ wives, servants and workers in Australia.

Jaki McCarrick’s exceptional play profoundly delves into the lives of these five women. All relate the horrors, and organized terrorism of British landlord evictions and burning of homes they’ve seen or experienced. Later in Act II as the truth is gradually revealed to be more terrible, it is mentioned that merchants made money from shipments of grain for export instead of feeding those starving when the crop failed in what has been identified as the Irish genocide. Each of the women at the outset are grateful to be fleeing “An Gorta Mor” raging in Belfast. However, a few regret leaving what has been their home for more than two decades. They are anxious to face the unknown.

The play opens as the women settle into their bunks and unpack their meager belongings. We watch as they change their street clothes to the blue uniform “orphan” dresses the matron and officials have given them to wear on their journey. Immediately, from their behavior and accents we understand these women are from different backgrounds, ages and environs.

Judith Noone (Caroline Strange), a Jamaican mixed-race woman drips worldly experience. She exposes the fact that Ellen Clarke (Labhaoise Magee) and Hannah Gibney (the golden voiced Mary Mallen) are public women/prostitutes, despite their pretensions that they have lived otherwise. Importantly, with a sense of autonomy as sex workers, these three have staved off death and starvation where others, bound up by religion with no way out, died and were buried in mass graves. Of all of the five “orphans,” Caroline Strange’s Judith, is the most grounded, authentic and realistic. Blunt and directed, she is a natural leader who chides and commands the rest of the women, reminding them of their purpose to rise up from the lower classes to respectability and success, so they might forge a new identity with this incredible opportunity.

Gradually, as we watch their interactions and the dynamic of the group as they squabble, insult and demean each other with words and sometimes with blows, McCarrick reveals that each woman, save Judith, is unable to confront the dark hell of guilt and self-loathing within. It is obvious that they’ve had to compromise their autonomy, integrity, goodness and self-respect living a life of extreme self-loathing as men’s footstools. Clarke and Gibney are familiar with each other as they throw epithets and verbally attack each other’s vulnerability. Judith is no less insulting in reminding them that they must control themselves and not be physically easy with the deckhands and men on the ship because an unwanted pregnancy will destroy their chances to meet accessible men and marry. Clearly, Clarke, Gibney and Judith have shared understanding and experiences that have been traumatic and soul-crushing.

On the other hand Sarah Jane Wylie (Sarah Street, and the day I saw the production, Owen Laheen) is quiet and mild-mannered. She stays to herself, sews a bonnet and doesn’t interact or insult the others, initially. She shares that her brother has been in Australia for almost two years and has encouraged her with stories of success and the promise of a land of prosperity and goodness.

Into their midst comes another girl whom they must make room for in their small living space before they sail. Molly Durcan (Aida Leventaki) is from Sligo. The others attempt to make her as comfortable as possible, though she is not in a bunk bed. They give her a piece of bread which she devours immediately; her frail and extremely thin body indicate the troubles she’s experienced. As they rearrange their living quarters, the ship is leaving port and a few go up to say goodbye to Ireland for the last time.

Judith forthrightly declaims she will never miss Belfast and plans to bury all of the memories in her new life and identity in Australia. She suggests the other women do the same. Hannah Gibney forgets her misery and is sentimental, putting “a false tint” on her life in Belfast. Judith confronts Hannah with the truth. She tells the others that her father sold her into prostitution for alcohol and must forget the terrors of a culture which provokes such behaviors. This revelation strips away Hannah’s pretense and denial. Judith encourages her and the others to redirect and focus on her new goals and new life in Australia. During the three month voyage, they must mentally prepare themselves with plans and goals for their future.

Mallen’s and Strange’s performance of this scene make this into an important moment. Not only do we understand their mixed emotions, though the life they leave behind is full of misery. Nevertheless, it is the only life they have known. Now, they face uncertainty. They haven’t read any travelogs to understand what they will be up against because there are none. And indeed, Hannah can’t read. When the ship leaves port, there is no turning back.

McCarrick identifies the dangers of the emigrant experience which still pertains today (exploitation, uncertainty, loss of identity). She highlights two important conditions for these women. They have been prostitutes plying their trade and skills as the only skills they know. Secondly, they are third class citizens. Though Hannah speaks of the Englishman that she will marry, rejecting her own nationality, this fantasy is an extreme that the other women point out to her.

We realize these women are naive; they are not prepared for what is going to happen to them, floating on a “wing and a prayer.” That it will be anything but a bed of roses is inferred by the irony of Hannah’s hopes, the vacancy of the other women’s responses and the hidden clues in McCarrick’s writing.

What is clear is that each of them has already “jumped off the cliff into the unknown.” Hoping for something better is the tremendous risk they take, born out of courage to seek freedom from the enslavement of poverty, paternalism and oppression by the British in Ireland. However, will they be able to continue with the courage of their convictions in Australia?

When Molly sees a rat by her sleeping space in the middle of the night, other arrangements are made. Judith softens her persona and allows her to join her in her bunk away from the rat. Thus, begins a relationship between the two women which the others may or may not be aware of that blossoms into love and affection. The intimate scene between them is beautifully, tastefully directed by Murphy and the fight and intimacy director Leana Gardella.

However, there is the danger that the Catholic judgments of the other women will censure and condemn the lovers. As it turns out Judith becomes Molly’s protector and Molly gives Judith her books, one of which includes the writings of Marx and Engels. Reading these, Judith begins to understand what Molly mentioned to them when she first arrived.

Women deserve their own rights and autonomy. In fact as Molly discusses her bold yearning to become an actress and play Puck, she also reveals that in other areas of Europe and the United States, women are gathering in groups and organizing for the right to vote. And women are speaking out against male chauvinism, paternalism, colonial oppression and exclusion which keeps women powerless. Judith’s knowledge grows and we understand that she and Molly have formed a close bond. At the least, the others begin a period of enlightened freedom they were never aware of before they boarded the Inchinnan.

However, in Act II all of what has been a hopeful blessing on the voyage as the women begin to grow their new, free identities, is upended during a roaring storm at sea. The storm’s effects are stylistically staged and shepherded by Murphy with the help of the movement director Erin O’Leary. As the women pray together for support during the frightening hurricane that threatens to swamp the ship and kill them, another storm breaks out among them. Tensions and tempers rage. An unimaginable lie is exposed. The revelation destroys and exposes all of their lies. Judith who has become her own person and lies for no one, attempts to ameliorate the emotional explosions of the women against each other to no avail.

This is no spoiler alert. Act II brings a magnificent resolution to the mysterious threads that have been left undone in Act I. The violence that occurs is shocking and believable. The sound and lighting designers (Caroline Eng, Michael O’Conner) do a wonderful job of striking our imaginations with the storm’s effects. They help to create the terror in the scene and the resulting aftermath.

By the conclusion Judith puts the mysterious pieces together of why Earl Henry Grey has created the Emigration Orphan Scheme with the clerics. The final blow of reality is made manifest which Judith and perhaps Sarah and Ellen understand, but Hannah is too broken to receive. Nevertheless, Judith affirms she will never give up on her hopes and new found self-empowerment on the Inchinnan. She is resolute and will continue to take care of Molly Durcan and nurture her with her love. Confronting her own lies and devastation, Sarah becomes more accepting and forgiving. However, it is Ellen who leaves us with the most vital of thoughts. “Who knows what dreams were born on the Inchinnan. If it’s not us who will have those freedoms you talked of…then maybe our daughters will…”

Belfast Girls is rich with history and incisive with characterizations that keep us engaged in this real drama of passion, anger at injustice and powerlessness and hope. The characters are portrayed with spot-on authenticity, by the wonderful ensemble. Kudos to Gregory Grene the music consultant who drew on the songs “Sliabb Gallion Brae,” “A Lark in the Clear Air,” “Mo Ghile Mear” and “Rare Willie,” all traditional Irish folksongs. Kudos to all the creative team and to China Lee, responsible for costume design and Rachael Geier for hair & wig design.

This is one to see, especially if you have Irish ancestors. If you don’t, but have ancestors who emigrated on ships that crossed the oceans to bring their progeny a better life in a more prosperous setting, the experience depicted in this production is directive and should draw you to learn more. For tickets and times to see Belfast Girls at the Irish Repertory Theatre go to their website: https://irishrep.org/

‘Two by Synge’ Directed by Charlotte Moore at The Irish Repertory Theatre

John Milton Synge stated of the “things which nourish the imagination, humor is one of the most needful, and it is dangerous to limit or destroy it.” Two of Synge works which employ satire and raucous humor to entertain and make fun of stereotypes found amongst the Irish country folk around 1903 are The Tinker’s Wedding and In the Shadow of the Glen. Directed by Charlotte Moore and starring wonderful actors from those often seen at The Irish Repertory Theatre, the enjoyable evening of these two Synge works flies by. One leaves with a belly-full of laughter and a smile on their face.

Both plays are set in 1903 County Wicklow in Ireland before Ireland was a Republic. And one imagines a fairly desolate area is the terrain where the humorous events take place in each work.

In The Tinker’s Wedding, the cast sings an upbeat folk song about a wedding where one pictures the happy townsfolk dancing and carousing “heel for heel and toe for toe, arm and arm and row on row, all for ‘Marie’s Wedding.'” The ebullient mood of the piece displayed in the music and vibrancy of the actors quickly shifts to argument between Michael Byrne (John Keating), and Sarah Casey (Jo Kinsella), who are companions but who have not yet married.

The irony is clear for couples getting married in Ireland and elsewhere. On the wedding day everyone is happy. Afterward, marriage is a different can of beans and couples are as miserable as they can stand each other to be. Interestingly, Michael Byrne and Sarah Casey have jumped to the difficulties without being married. And now with a marriage ceremony to be conducted by the priest who is nearby, perhaps they may have some joy.

As they argue about the ring which Michael makes for Sarah which doesn’t fit, Michael questions why they need to be married at all. Sarah replies that she is renown in the county as the Beauty of Ballinacree and could get a number of the men who have acknowledged her beauty to marry her if Michael refuses. She says this to spur Michael from his intractable reluctance. However, Michael is having none of her boasting and doesn’t in the least act jealous, but uses her self-puffery as an occasion for irony and humor. He likens other individuals’ comments about her to the names of the horses that race at Arklow and refers to her easily swallowing the words of “liars.” Their banter is humorous and we question why they should be married after the fact of their having been together, especially since Sarah threatens to leave him because of his funny but insulting retorts.

When the Priest (Sean Gormley) comes into their midst, Sarah bargains with him for the money he wants to marry them. We question the Priest’s “high and mighty” attitude and think that he is classist because he won’t perform the ceremony for free for tinkers who roam the country side, have no roots and persuing questionable activities in the dark of the moon. Later in the play it comes out why he is reluctant; he is aware of their thefts in the neighborhood, though they manage to get away with it. Nevertheless, he agrees to marry them for money and a “tin can” that Michael has been laboring over.

Enter Mary Byrne (the humorous Terry Donnelly), Michael’s mother. Tipsy, cradling a bottle of alcohol like a baby, she is a humorous caricature of one who obviously enjoys slaking her thirst daily. For hospitality and “friendship,” she offers a drink to the Priest to manipulate him to favor her son and daughter-in-law’s marriage request.

Afterwards, when Mary Byrne is alone, she sees an opportunity to steal from her son an item promised to the Priest which she then will sell for drink. The complications arise between the characters. Mary Byrne throws the couple’s wedding plans into the bog after they discover she double crosses them. They double cross the priest who vows not to get revenge. However, he has a better plan for their reckoning which they can never flee, though they scramble with their belongings far away from the praying cleric.

In the Shadow of the Glen, a Tramp (John Keating), knocks on Nora Burke’s (Jo Kinsella) door. Lonesome with her husband possibly just having died since he hasn’t moved or made a peep, Nora opens the door and invites him in from the storm. Hospitably, she offers the Tramp a drink and tells him the story of her husband who she fears is dead and who cursed her not to lay a hand on him if he died in his bed. Only his sister can prepare him for the funeral ceremony and burial, Nora tells the Tramp. Their conversation is laced with spooky mystery as the subjects range from the quick to the dead and Nora explains that her husband was a queer old man who went up to the hills where he was “thinking dark thoughts.”

When she asks the Tramp to see if her husband Dan Burke (Sean Gormley) is cold and dead, the Tramp protests that he doesn’t want to bring down the curse on his own head. They continue to discuss their tribulations and the death of one they both know until finally Nora tells him she must find the young farmer who would do chores for them and who the Tramp ran into on his way toward the Burkes. She will ask the farmer to stop by with her, check on her husband. If he is dead, the next morning he can tell the village that Dan Burke has passed. Most possibly, Burke’s sister who lives about ten miles away will then be notified. Nora asks the Tramp to stay with her husband’s dead body until she returns.

One anticipates what will happen next which is absolutely hysterical. The hijinx continue after Nora returns with the young Michael Dara (Ciaran Bowling), who is well off and appears to be interested in Nora’s inheritance from Dan Burke’s estate. With the body not yet “cold” nor burned in ashes, Dara makes plans for Nora to be his wife. However, she is not so easily persuaded. And as events transpire, the humorous explosions (I belly laughed so heard) heighten then resolve into an ironic ending.

Charlotte Moore strikes just the right tone, shepherding her cast into the humor inherent in Synge’s characterizations, as he satirizes these couples and the relationships that bind them that can’t quite be referred to as loving. In each instances we understand the importance of money, the fear of destitution and the solitude of the environs contributing to the dynamic and topsy turvy events.

The music and song that introduces each work sets the scene and establishes the tenor of Synge’s plays. Marie’s Wedding appropriately opens The Tinker’s Wedding sung by the entire cast and accompanied on guitar by Sean Gormley. As the character of Mary in The Tinker’s Wedding, Terry Donnelly sings with lyrical humor “The Night Before Larry Was Stretched,” a traditional Irish ballad, and two refrains, one from “A Lonesome Ditch in Ballygan,” and the other from “Whisper With One.” Between the Acts in The Tinker’s Wedding, Sean Gormley sings and performs his original song, “A Smile Upon My Face.” In the second play, In The Shadow of the Glen, Ciaran Bowling’s clear, bell-ringing voice beautifully interprets “Red is the Rose,” a traditional Gaelic ballad.

Moore has cleverly employed the space of the W. Scott McLucas Studio Theatre to suggest the settings with whimsy and attention to details in the play. The economy of props and accessibility to them is thoughtful and acute as always, thanks to creatives Daniel Geggatt (set design), David Toser (costume design), Michael O’Connor (lighting design), Nathanael Brown (co-sound design) Kimberly S. O’Loughlin (co-sound design).

Two by Synge is a highly enjoyable and finely presented example of why Synge’s work lasts in its evocation of human nature and particular Irish themes conveyed with light hearted humor and grace. For tickets and times go to the Irish Repertory Theatre website: https://irishrep.org/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw6pOTBhCTARIsAHF23fLAjBdNTydq_KkznLEVR1YEogYRKeF4w1gWXnS8RFwGqLnyR5GBZTMaAmfpEALw_wcB

‘A Touch of the Poet’ The Irish Rep’s Brilliant Revival Exceeds Its Wonderful Online Performance. Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Poet’ is Amazing Glorious Theater!

From the moment Cornelius “Con” Melody (Robert Cuccioli) appears, shaking as he holds onto the stair railing of the beautifully wrought set by Charlie Corcoran, we are riveted. Indeed, we stay mesmerized throughout to the explosive conclusion of the Irish Repertory Theatre’s A Touch of the Poet by Eugene O’Neill. Compelled by Cuccioli’s smashing performance of Con, we are invested in this blowhard’s presentiments, pretenses and self-betrayal, as he unconsciously wars against his Irish heritage. Con is an iconic representative of the human condition in conflict between soul delusion and soul truth.

What will Con’s self-hatred render and will he take down wife Nora and daughter Sara (the inimitable pairing of Kate Forbes and Belle Aykroyd), in his great, internal classicist struggle? Will Con finally acknowledge and accept the beauty and enjoyment of being an Irishman with freedom and hope? Or will he continue to move toward insanity, encased in the sarcophagus image of a proper English gentleman? This is the identity he bravely fashioned as Major Cornelius Melody to destroy any smatch of Irish in himself. O’Neill’s answers in this truly great production of Poet are unequivocal, yet intriguing.

The conflict manifests in the repercussions of the drinking Con takes on with relish. So as Cuccioli’s Con attempts to gain his composure and stiffly make it over to a table in the dining room of the shabby inn he owns, the morning after a night of carousing, we recognize that this is the wreck of a man physically, emotionally, psychically. His shaking frame soothed by drink, which wife Nora (Kate Forbes), brings to him in servile slavishness, is the only companion he wants, for in its necessity as the weapon of destruction, it hastens Con’s demise. The beloved drink stirs up his bluster and former stature of greatness that he has lost forever as a failed Englishman and even bigger failure as comfortable landed gentry in 1828 Yankee country near Boston.

Director Ciarán O’Reilly and the cast heighten our full attention toward Con’s conflict with the romantic ideal of himself and the present reality that will eventually drive him to a mental asylum or a hellish reconciliation with truth. All of the character interactions drive toward this apotheosis. The actors are tuned beautifully in their portrayals to magnify the vitality of this revelation.

Nora (Forbes is authentic and likeable), is the handmaiden to Con’s process of dissolution. In order to fulfill her own glorified self-reflection and identity in loving this once admirable gentleman, she coddles him. Riding on the coattails of her exalted image of Con, she maintains beauty in her self-love. She loves him in his past glory, for after all, he chose to be with her. So Nora must abide in his every word and deed to maintain her loyal happiness, taking whatever few, kind crumbs he leaves for her under the table of their marriage. As a result, she would never chide or browbeat Con to quit the poison that is killing him.

The good whiskey he proudly provides for himself and friends like Jamie Cregan (the excellent Andy Murray), to help maintain the proper stature of a gentleman, steadies his mind. The whiskey also makes him feel in control of his schizoid personas. He clearly is not in control and never will be, unless he undergoes an exorcism. The audience perversely finds O’Neill’s duality of characterizations in Con and the others amusing if not surprising.

Cuccoli’s Con at vital moments rejects the painfully failed present by peering into his mirrored reflection to quote Lord Byron in one or the other of two mirrors positioned strategically on the mantel piece and a wall. There, fueled by the alcohol, he re-imagines the glorious military man of the Dragoons as he stokes his pride. Yet, with each digression into the past, he torments his inner soul for reveling in his failed delusion.

Likewise, each insult he lashes against Nora, who guilty agrees with him for being a low Irish woman, both lifts him and harms him. It is the image of the Major ridiculing Nora because of the stink of onions in her hair one moment, and in self-recrimination, apologizing moments after for his abusiveness. In his behavior is his attempt to recall and capture his once courageous, successful British martial identity, while rejecting the Irish humanity and decency in the deep composition of his inner self.

Always that true self comes through as he recognizes his cruelty. He behaves similarly with Sara, bellicose in one breath, apologetic in the next, fearful of her accusatory glance. In this production Con’s struggle, Nora’s love throughout and Sara’s resistance and war with herself and her father is incredibly realized and prodigiously memorable. O’Reilly and the cast have such an understanding of the characters and the arc of their development, it electrified the audience the night I saw it. We didn’t know whether to laugh (the humor originated organically as the character struggles intensified), or cry for the tragedy of it. So we did both.

Con’s self-recrimination and self-hatred is apparent to Nora whose love is miraculously bestowed. His self-loathing is inconsequential to Sara, who torments him with an Irish brogue, lacerating him about his heritage and hers, which the “Major” despises, yet is his salvation, for it grounds him in decency. Sara and Nora are the bane of his existence and likewise they are his redemption. If only he could embrace his heritage which the “scum” friends who populate his bar would appreciate. If only he could destroy the ghost of the man he once was, Major Cornelius Melody, who had a valiant and philandering past, serving under the eventually exalted Duke of Wellington.

Through the discussions of Jamie Cregan with Mick Maloy (James Russell), we learn that the “Major identity” caused Con to be thrown out of the British military and forced him to avoid disgrace by settling in America with Nora and Sara. We see it causes his decline into alcoholism, destroys his resolve and purpose in life, and dissipates him mentally. It is the image of pretension that caused the bad judgment to be swindled by the Yankee liar who sold him the unproductive Inn. Sadly, that image is the force encouraging the insulting, emotional monster that abuses his wife and daughter. And it is a negative example for Sara who treats him as a blowhard, tyrant fool to vengefully ridicule and excoriate about his class chauvinism, preening airs and economic excesses (he keeps a mare to look grand while riding). It is the Major’s persona which brings them to the brink of poverty.

The turning point that pushes Con over the edge comes in the form of a woman he believes he can steal a kiss from, Deborah Hartford, the same woman whose intentions are against Sara and her son Simon Hartford falling in love. Without considering who this visiting woman might be, Con assumes the Major’s pretenses and we see first hand how Con “operates” with the ladies. His romanticism awkwardly emerges, left over from his philandering days with women who fell like dominoes under his charms. He is forward with Hartford who visits to survey the disaster her son Simon has befallen, under the spell of Sara’s charms, behavior not unlike Con’s. The scene is both comical and foreboding. From this point on, the events move with increasing risk to the climactic, fireworks of the ending.

As Deborah Hartford, Mary McCann pulls out all the stops in a performance which is grandly comical and real, with moment to moment specificity and detail. When Con attempts to thrust his kiss upon her, there were gasps from the audience because she is a prim Yankee woman of the upper classes who would find Con’s behavior low class and demeaning. That he “misses” the signs of who she is further proves his bad judgment. Sara is appalled and Nora, not jealous, makes excuses for him satisfying herself. The scene is beautifully handled by the actors with pauses and pacing to maximum effect.

McCann’s interaction with Aykroyd’s Sara is especially ironic. Deborah Hartford’s speech about the Hartford family male ideals of freedom and lazy liberty that forced the Hartford women to embrace their husbands’ notions by taking up the slave trade is hysterical. As she mildly ridicules Simon’s dreams to be a poet and write a book about freedom from oppressive, nullifying social values, she warns Sara against him. It is humorous that Sara doesn’t understand what she implies. Obviously, Deborah Hartford suspects Sara is a gold digger so she is laying tracks to run her own train over any match Sara and her son would attempt to make. After discovering the economically challenged, demeaned Melody family, Hartford informs her husband who sends in his man to settle with the Melodys.

Together McCann and Aykroyd provide the dynamic that sets up the disastrous events to follow. Clearly, Sara is more determined than ever to marry Simon and as the night progresses, she seals their love relationship with Nora’s blessing, until Nora understands that her daughter walks in her own footsteps in the same direction that she went with Con. Unlike Nora, however, Sara is not ashamed of her actions.

O’Neill’s superb play explores Con’s past and its arc to the present, revealing a dissipated character at the end of his rope. Wallowing in the Major’s ghostly image, Con vows to answer Mr. Hartford’s insult of sending Nicholas Gadsby (John C. Vennema looks and acts every inch the part), to buy off Sara’s love for Simon and prevent their marriage. After having his friends throw out the loudly protesting Gadsby, Con and Jamie Cregan go to the Hartfords to uphold the Major’s honor in a duel. Nora waits and fears for him and in a touching scene when Sara and Nora share their intimacies of love, Nora explains that her love brings her self-love and self-affirmation. Sara agrees with her mother over what she has found with Simon. The actors are marvelous in this intimate, revelatory scene.

The last fifteen minutes of the production represent acting highpoints by Cuccioli, Forbes, Aykroyd and Murray. When Con returns alive but beaten and vanquished, we acknowledge the Major’s identity smashed, as Con sardonically laughs at himself, a finality. With the Major’s death comes the hope of a renewal. Finally, Con shows an appreciation of his Irish heritage as he kisses Nora, a redemptive, affirming action.

O’Neill satisfies in this marvelous production. The playwright’s ironic twists and Con’s ultimate affirmation of the foundations of his soul is as uplifting as it is cathartic and beautiful. Nora’s love for Con has finally blossomed with the expiation of the Irishman. It is Sara who must adjust to this new reality to redefine her relationship with her father and reevaluate her expectation of their lives together. The road she has chosen, like her mother’s, is hard and treacherous with only her estimation of love to propel her onward.

From Con’s entrance to the conclusion of Irish Repertory Theatre’s shining revival of Eugene O’Neill’s A Touch of the Poet, presented online during the pandemic and now live in its mesmerizing glory, we commit to these characters’ fall and rise. Ciarán O’Reilly has shepherded the sterling actors to inhabit the characters’ passion with breathtaking moment, made all the more compelling live with audience response and feeling. The production was superbly wrought on film in October of 2020. See my review https://caroleditosti.com/2020/10/30/a-touch-of-the-poet-the-irish-repertory-theatres-superb-revival-of-eugene-oneills-revelation-of-class-in-america/

Now, in its peak form, it is award worthy. Clearly, this O’Neill version is incomparable, and O’Reilly and the actors have exceeded expectations of this play which has been described as not one of O’Neill’s best. However, the production turns that description on its head. If you enjoy O’Neill and especially if you aren’t a fan of this most American and profound of playwrights, you must see the Irish Rep presentation. It is not only accessible, vibrant and engaging, it deftly explores the playwright’s acute themes and conflicts. Indeed, in Poet we see that 1)classism creates personal trauma; 2)disassociation from one’s true identity fosters the incapacity to maintain economic well being. And in one of the themes O’Neill revisits in his all of his works, we recognize the inner soul struggles that manifest in self-recrimination which must be confronted and resolved.

Kudos to the creative team for their superb efforts: Charlie Corcoran (scenic design), Alejo Vietti & Gail Baldoni (costume design), Michael Gottlieb (lighting design), M. Florian Staab (sound design), Ryan Rumery (original music), Brandy Hoang Collier (properties), Robert-Charles Vallance (hair & wig design).

For tickets and times to the Irish Repertory Company’s A Touch of the Poet, go to their website: https://irishrep.org/show/2021-2022-season/a-touch-of-the-poet-3/