Blog Archives

‘Gutenberg! The Musical!’ Featherbrained, Loopy, Josh Gad and Andrew Rannells Shine!

If you are looking for laughs and ridiculous fun, Gutenberg! The Musical! is the show for you. Thanks to the superbly wacky performances in this farce where Josh Gad and Andrew Rannells make a twosome of bat-sh*t silliness, Gutenberg! is a standout. Currently running at the James Earl Jones Theatre with one intermission in a two hour time slot, the zaniness is a treat to take you out of yourself. And who doesn’t need to “forget your troubles and get happy” in these times that try all of our souls?

The premise is well known: amateurs strike out for Broadway, draw in by the allurement of the “great white way.” In this iteration, two guys from New Jersey decide to toss the dice and bankroll a musical they’ve written to pitch it at a backer’s audition they set up at the James Earl Jones Theatre for a one night rental. Because they have to scrounge up the money by using the last dime of their inheritances, they can only afford a bare bones cast. Both play a total of twenty parts. They never change costumes except for hats in bold, black print which state their roles. For accompaniment they’ve hired a three-piece, local band that plays weddings, bar mitzvahs, retirement parties, etc.

Their thought is if they are good enough (ah, there’s the rub), they will get funding from producers to mount their musical on Broadway. Thus, Gutenberg! is theater “vérité,” happening with immediacy. Sitting in the audience, we are told, are various producers who’ve received invites. Thus, the audience bears witness to whether or not these Jersey guys have what it takes to sizzle and shine or fizzle and die on the vine of their dreams.

Scott Brown and Anthony King (book, music and lyrics), launch the show into the stratosphere of inanity. Not only are Bud (Josh Gad) and Doug (Andrew Rannells) below average talents, they have little expertise about what makes a musical or any show for that matter. Furthermore, their lyrics, rhymes and meaning rival the simplicity of Dr. Seuss.

But all is not lost. Interestingly, Dr. Seuss is extremely popular because it capitalizes on being silly. Additionally, the wild duo are winning and lovable. What Bud and Doug lack in talent and expertise, they make up for with enthusiasm, joie de vivre and hilarious, charming schtick.

As a side note, Gad and Rannells, who haven’t been together since Book of Morman, are terrific in curtailing their exceptional talent just enough to be a tad off, making their portrayals as Bud and Doug even funnier. Of course, this adds to the inside joke about who they really are and what they are capable of. Indeed, the audience was tuned to the inside jokes.

Gad and Rannells have fun playing it to the hilt with tongue in cheek direct addresses to the audience and a shattering of the fourth wall, as they move along the plot about a dry subject, the life and times of Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the printing press. As it turns out Gutenberg is a topic about which little is written and much can be embellished and fictionalized. That is why Bud and Doug have found it to be a glorious subject for a “fantastic” musical.

Ironically, referring to their content as historical fiction, they share little factual information about the man and the time. In falling back on fabrication, which currently is trending in political news and the radical conservative, nihilistic, QAnon wing of the “Republican” Party, Bud and Doug’s fantastic tale is hugely satiric. It indirectly points the finger at the last seven years of Trumpism, when the playing field of misinformation became normalized through the efforts of conservative media. Lies of omission, conspiracy theories and sheer made-up junk swanned as legitimate and newsworthy.

Take for example reports on Italian space lasers causing the 2020 election to be stolen from former president Donald Trump. (Look up recently convicted Trump lawyer Sidney Powell, if my reference to Italian space lasers eludes you.) Such theories are inane fabrications such as those found in this musical.

On the other hand for all its guffaws, belly laughs and puerility, Gutenberg! is as serious as a heart attack. If you peek underneath the abundant blanket of hysteria, it actually makes grave points.

That Scott Brown and Anthony King convert the momentous occasion of the birth of Gutenberg’s printing press, a turning point in history, into a farce that nuances themes about the perils of illiteracy, is profound as well as riotous. In truth illiteracy and “not reading books” is disastrous, when considering the culture wars of the South and their twisted turn into banning books. Making indirect inferences to the QAnon pride of ignorance against the elitism of the educated, Gutenberg! twits us with its ridicule about our present time.

This is especially so with the musical’s humorous, historical reminder of how ignorance leaves an open door for the power hungry. In its Act II arc of development, after the printing press has been invented, the villainous, devilish monk completes his scheme to target Gutenberg and destroy his press. Representing the power of the church which historically exploited the ignorant and illiterate, we understand the benefits of keeping the uneducated, non-reading masses brainwashed, oppressed and afraid.

In portraying the monk with a nefarious purpose, Gad is riotously funny. He pings all the notes of the stereotypical wicked, leaving the audience LOL. Of course, his crafty portrayal stings, if one moves beyond the laughter to the quiet message underneath. Despotism only works well with the uneducated, non-reading, non-thinking masses who are often too distracted to distinguish the truth from fiction and lies.

Throughout the winding action which involves anti-semites, Gutenberg’s fictional German town of Schlimmer, a wine press becoming a printing press, a pretty, violent white cat named Satan, a maid named Helvetica, pencils that kill, Brechtian breaks and commentary about the musical, and so much more, Gad and Rannells create their comedic, whirlwind sketches at Alex Timber’s breakneck pace. Seamlessly stirring the narrative segues, then plunging back into the action as they don the various hats of the characters they portray to trigger spot-on caricatures with their voices and gestures, they send up the “politically warped” stereotypes and spin this delightful musical farce with lightening speed.

We have been led into the “secret world” of a backer’s audition for a production that is a loser and a winner. Maybe with a little revision, a tweak here and there, a consolidated cast, a reworking of the more incredible elements, a producer will envision its commercial vitality? Maybe not. You have to see it to find out if the producers line up to sign on or hold their noses and back out quietly.

Importantly, during the process, Gad’s Bud and Rannells’ Doug steer the audience from joke to quip to zany song with an aplomb that is exhaustive and exhausting. Assisted by Scott Pask’s scenic design of the stripped down stage, Emily Rebholz’s costume design which is appropriate for Doug and Bud’s dorkish affability, Jeff Croiter’s lighting design and Tommy Kurzman’s hair design, the actors fulfill Timber’s tone and vision for this seemingly facile, but humorously febrile, profound musical. M.L. Dogg and Cody Spencer’s sound design is spot on; I could hear every word.

Kudos goes to the orchestra which includes Marco Paguia (conductor/keyboard 1), Amanda Morton (associate conductor/keyboard 2) and Mike Dobson (percussion). Additional arrangements are made by Scott Brown and Anthony King. T.O. Sterrett is responsible for music supervision, arrangements and orchestrations.

This is one to see for the fun of it. It is also a sardonic criticism of our time, which, thankfully, doesn’t slam one over the head with pretentious probity. For tickets go to the Box Office at 138 West 48th Street or visit their website online https://gutenbergbway.com/ It closes January 28th.

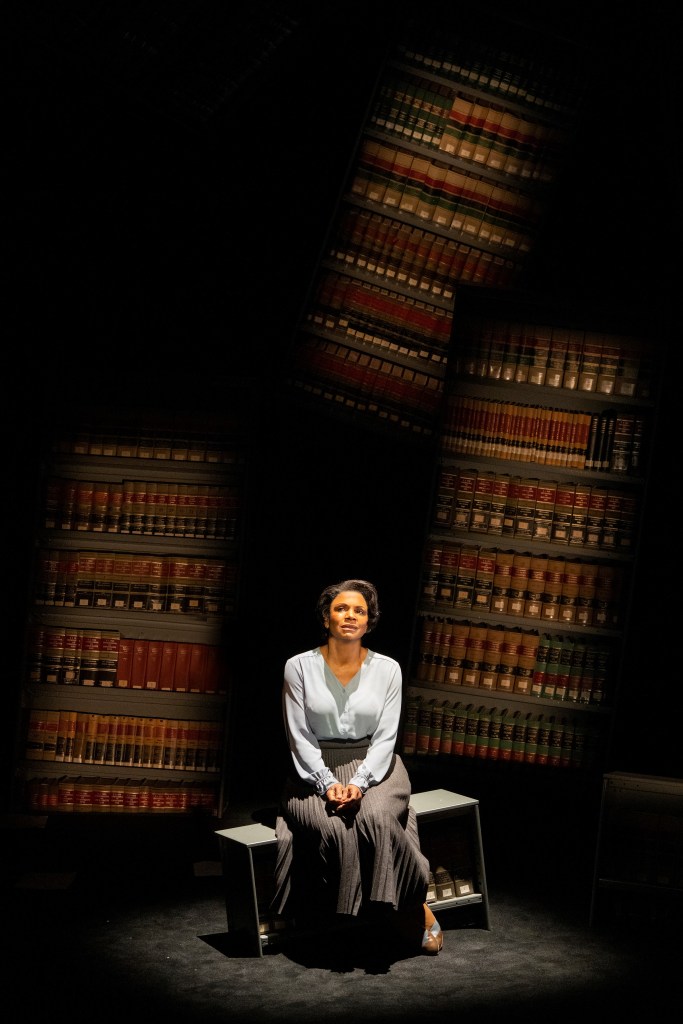

‘Ohio State Murders,’ Audra McDonald’s Performance is Stunning in This Exceptional Production

For her first Broadway outing Adrienne Kennedy’s Ohio State Murders has been launched by six-time Tony award winner Audra McDonald into the heavens, and into history with a magnificent, complexly wrought and richly emotional performance. The taut, concise drama about racism, sexism, emotional devastation and the ability to triumph with quiet resolution is directed by Kenny Leon and currently runs at the James Earl Jones Theatre until 12 February. It is a must-see for McDonald’s measured, brilliantly nuanced portrayal of Suzanne Alexander, who tells the story of budding writer Suzanne, in a surreally configured narrative that blends time frames and requires astute listening and thinking, as it enthralls and surprises.

This type of work is typical of Kennedy whose 1964 Funnyhouse of a Negro won an Obie Award. That was the first of many accolades for a woman who writes in multiple genres and whose dramas evoke avant garde presentations and lyrically poetic narratives that are haunting and stylistically striking. As one who explores race in America and has contributed to literature, poetry and drama expressing the Black woman’s experience without rhetoric, but with illuminating, symbolic, word crafting power, Kennedy has been included in the Theater Hall of Fame. In 2022 she received the Gold Medal for Drama from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The Gold Medal for Drama is awarded every six years and is not bestowed lightly; only 16 individuals including Eugene O’Neill have been so honored.

This production of Ohio State Murders remains true to Kennedy’s wistful, understated approach to the dramatic, moving along an arc of alternating emotional revelation and suppression in the expose of her characters and their traumatic experiences. Leon and McDonald have teased out a 75 minute production with no intermission, intricate and profound, as Kennedy references and parallels other works of literature to carry glimpses of her characters’ complexity without clearly delineating the specifics of their behaviors. In the play much is suggested, little is clarified. Toward the unwired conclusion we find out a brief description of how the murders occurred and by whom. The details and the motivations are distilled in a few sentences with a crashing blow.

Much is opaque, laden with sub rosa emotion, depression, heartbreak and quiet reflection couched in remembrances. The most crucial matters are obviated. The intimacy between the two principals which may or may not be glorious or tragic is invisible. That is Kennedy’s astounding feat. Much is left to our imaginations. We can only surmise how, when and where Suzanne and Robert Hampshire (Bryce Pinkham in a rich, understated and austere portrayal) who becomes “Bobby” got together and coupled when Suzanne supposedly visited his house. Their relationship mirrors that of the characters in Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy. It is this novel which first brings the professor and student together in mutual admiration over a brilliant paper Suzanne writes and he praises.

What is mesmerizing and phenomenal about Kennedy’s work is how and why McDonald’s Suzanne follows a process of revelation not with a linear, chronological storytelling structure, but with an uncertain, in the moment remembering. McDonald moves “through a glass darkly,” unraveling recollections, as her character carefully unspools what happened, sees it anew as it unfolds in her memory, then responds to the old and new emotions the recalled memories create.

Audra McDonald is extraordinary as Suzanne Alexander, who has returned to her alma mater to discuss her own writing which has been published and about which there are questions concerning the choice of her violent images. The frame of Suzanne’s lecture is in the present and begins and ends the play. By the conclusion Suzanne has answered the questions. Kennedy’s circuitous narrative winds through flashback as Suzanne relates her experiences at Ohio State when she was a freshman and her movements were dictated by the bigotry that impacted her life there.

In the flashback McDonald’s Suzanne leaps into the difficult task of familiarizing us with the campus and environs, the discrimination, her dorm, roommate Iris Ann (Abigail Stephenson) and others (portrayed by Lizan Mitchell and Mister Fitzgerald), all vital to understanding Suzanne’s story about the violence in her writing. Importantly, McDonald’s Suzanne begins with what is most personal to her, the new world she discovers in her English classes. These are taught by Robert Hampshire, (the astonishing Bryce Pinkham) a professor new to the college. Reading in wonder and listening to his lectures, Suzanne’s fascination with literature, writing and criticism blossoms under his tutelage.

Within the main flashback Kennedy moves forward and backward, not allowing time to delineate what happened, but rather allowing Suzanne’s emotional memories to lead her storytelling. After authorities expel her from Ohio State, she lives with her Aunt and then returns with her babies to work and live with a family friend in the hope of finishing her education. During this recollection she refers to the time when she lived in the dorm and was disdained by the other girls.

Kennedy anchors the sequence of events in time by using the names of individuals Suzanne meets. For example when she returns after she has been expelled, she meets David (Mister Fitzgerald) who she dates and eventually marries after the Ohio State murders. What keeps us engrossed is how Suzanne fluidly merges time fragments within the years she was at the college. She digresses and jumps in memory as she retells the story, as if escaping from emotion in a repressive flash forward, until she can resume her composure. At the conclusion, Suzanne references the murders of her babies.

Thus, with acute, truncated description that is both poetic and imagistic, McDonald’s Suzanne slowly breaks our hearts. McDonald elucidates every word, every phrase, imbuing it with Suzanne’s particular, rich meaning. Though the character is psychologically blinded and perhaps refuses to initially accept who the killer of her babies might be, there is the uncertainty that she may know all along, but is loathe to admit it to her self, because it is incredibly painful. At the conclusion when she reveals the murderer’s identity and events surrounding both murders, she is remote and cold, as is the snow falling behind outside the crevasse. At that segment McDonald’s unemotional rendering triggers our imaginations. In a flash we understand the what and why. We receive the knowledge as a gut-wrenching blow. Fear has encouraged the murderer in a culture whose violence and racism bathes its citizens in hatred.

When McDonald’s Suzanne Alexander brings us back to the present as she pulls us up with her from the recesses of her memory, we are shocked again. We have been gripped and enthralled, swept up in the events of tragedy and sorrow, senseless violence and loss. The question of why bloody imagery is in Suzanne’s writing has been answered. But many more questions have been raised. For example, in an environment of learning and erudition, how is the murder of innocents possible? Isn’t education supposed to help individuals transcend impulses that are hateful and violent? Kennedy’s themes are horrifically current, underscored by mass shootings in Ulvade, Texas and other schools and colleges across the nation since this play was written (1992). At the heart of such murdering is racism, white domestic terrorism, bigotry, hatred, inhumanity.

The other players appear briefly to enhance Suzanne’s remembrances. Pinkham’s precisely carved professor Hampshire reveals all the clues to his nature and future actions in the passages he reads to his classes from the Hardy novel, then Beowuf and in references to King Arthur and the symbol of the “abyss” he discusses in two lectures Suzanne attends. All, he delivers tellingly with increasing foreboding. Indeed, the passages are revelatory of what he is experiencing symbolically in his soul and psyche. When Suzanne describes his physical presence during the last lecture, when she states he is looking weaker than he did when he taught his English classes, it is a clue. Pinkham’s Hampshire is superbly portrayed with intimations of the quiet, profound and troubled depths of the character’s inner state of mind.

Importantly, Kennedy, through Suzanne’s revelations about the university when she was a freshman, indicates the racism of the student body as well as the bigotry of the officials and faculty, which Black students like Suzanne and Iris must overcome. There is nothing overt. There are no insults and epithets. All is equivocal, but Suzanne feels the hatred and the injustice regarding unequal opportunities.

For example it is assumed that she cannot “handle” the literature classes and must go through trial classes to judge whether she is capable of advanced work as an English major. When she tells professor Hampshire, he insists that this shouldn’t be happening. Nevertheless, he has no power to change her circumstances, though he has supported and encouraged her writing. The college’s bigotry is entrenched, as she and other Black women are discouraged in their studies and forced out surreptitiously so that they cannot complain or protest.

Kenny Leon’s vision complements Kennedy’s play. It is imagistic, minimalistic and surreal, thanks to Beowulf Boritt’s scenic design, Jeff Sugg’s projection design, Allen Lee Hughes lighting design and Justin Ellington’s sound design. At the top of the play there are two worlds. We see black and white projections of of WWII and the aftermath through a v-shaped crevasse that divides the outside culture and the interior of the college in the library symbolized by faux book cases. These are suspended in the air and move around symbolically following what Suzanne discusses and describes.

The books are a persistent irony and heavy with meaning. They sometimes serve as a backdrop for projections, for example to label areas of the campus. On the one hand they represent a lure to Suzanne who venerates literature. They suggest the amalgam of learning that is supposed to educate and improve the culture and society. However, the bigoted keepers of knowledge in their “ivory” towers use them as weapons of exclusion and inhumanity, psychologically and emotionally, harming Blacks and others who are not white or who are considered inferior. Leon’s vision and the artistic team’s infusion of this symbolism throughout the play are superb.

In the instance of the one individual who appreciates Suzanne’s writing, the situation becomes twisted and that too, becomes weaponized against her. However, that she has been invited back to her alma mater all those years later to discuss her writing indicates the strength of her character to overcome the incredible suffering she endured. At the conclusion of her talk in the present she reveals her inner power to leap over the obstacles the bigoted college officials put before her. Her return so many years later is indeed a triumph.

Leon and the creative team take the symbolism of rejection, isolation, emotional coldness and inhumanity and bring it from the outdoors to the indoors. Beyond the crevasse in the wintertime environment, the snow falls during Suzanne’s description of events. Eventually, by the end of the play, the exterior and interior merge. The violence we saw at the top of the play in pictures of the War and its aftermath has spread to Ohio State. The snow falls indoors. Finally, Suzanne Alexander is able to publicly speak of it openly and honestly after discovering there was a cover-up of the truth that even her father agreed to out of shame and humiliation.

Ohio State Murders is a historic event that should not be missed. When you see it, listen for the interview of Adrienne Kennedy before the play begins as the audience is seated. She discusses her education at Ohio State and the attitudes of the faculty and college staff. Life informs art as is the case with Adrienne Kennedy’s wonderful avant garde play and this magnificent production.

For tickets and times to to their website: https://ohiostatemurdersbroadway.com/