Blog Archives

‘The Blood Quilt,’ Threading an Ancestral Masterpiece of Hope

The Blood Quilt

In her ambitious layering of the story of four half-sisters who gather to finally lay to rest their recently deceased mother, Katori Hall, with astute direction by Lileana Blain-Cruz, focuses on complex family dynamics, jealousies, misunderstandings and secrets. The confluence of emotions roil the souls of each sister and a teenage niece, paralleling the stormy seas which crash waves onto the setting, Kwemera Island, Georgia. The culmination of fiery anger, pain and sadness releases in the rituals of quilting and the soul healing of family connections in mysticism, dance and song.

By the conclusion of the two-act drama, currently at LCT’s Mitzie E. Newhouse until December 29, we know the fabric of each of the sister’s lives. As a result we thrill with them when they are able to reconcile their inner wounds and cast them into the sea. It is in the waters fronting the small country cabin they call home, where ancestors have been buried in a symbolic tradition that the eldest sister Clementine speaks of with power, “We all came from the water and we all must return.”

The characters are the patchworks that make up the family masterpiece

Much of the beauty of Hall’s drama, laced with comedic elements, comes from her precise characterizations of the disparate sisters who share the same mother but have different fathers. They are the patchworks that make up the last quilted masterpiece that their mother designed and they gather to finish.

Clementine, Gio, Amber

Clementine (Crystal Dickinson), is the eldest, who lives in the incredible ancestral home. Adam Rigg’s set design hums with authenticity, warmth and life. The cabin is decorated with generational family quilts that cover walls and the balcony railing, each colorful, individual, symbolic. Family ownership of the “chic” cabin with the sea in its front yard is in jeopardy because of unpaid taxes which their mother ignored, while keeping her delinquency a secret from her children.

Clementine, who lives there and became caretaker of their dying mother, best knows the rituals of their Jernigan ancestors. A root worker of potions and spells, she speaks Geechee (from their Gullah Geechee heritage), and emotionally archives their legacy, back to the first slave ancestors that lived and worked on the plantations in the area. She is a master of the rituals and celebration of their heritage through quilting which they practice yearly under her direction. This summer when the play opens, the sisters and their niece Zambia (Mirirai), gather together to complete the last quilt their dying mother/grandmother designed, as they symbolically release her to another plane of existence.

Gio (Adrienne C. Moore), is the second oldest, a roughly hewn, hard drinking, Mississippi cop, who is resentful and jealous of her youngest sister Amber (Lauren E. Banks). Gio’s rancor runs deep because of a traumatic, covert incident unbeknownst to Amber but related to Amber’s father that happened when Gio was a teenager. Sensitive to her own misery, burying hurts from her divisive relationship with their mother who abused her, Gio’s moods, aided by alcohol, swing widely as she peppers them with spicey swearing and insults directed mostly at youngest sister Amber.

Amber is the beauty and reputed favorite of their mother because of her accomplishments. She went to an Ivy league college and eventually becomes an entertainment lawyer of means. Because she missed the last three summers of their quilting ritual, and their mother’s funeral service, her estrangement from her sisters and the difference between her lifestyle and theirs is apparent.

Despite Gio and Clementine’s “guilting” her for not coming to the funeral, we discover Amber was emotionally the closest to her mother. She paid for her cancer treatments, phoned her often and even assisted the family after she left the homestead for California. In spite of their geographical and emotional separation, she paid for her sisters’ needs when they asked her, and especially pays for niece Zambia’s tuition in a private school.

Zambia and Cassan

It is Zambia who is the linchpin of the wayward, patchwork family that hangs together by a slender thread as each sister expels her angst and self-recrimination to each other. However, Hall uses Zambia and her mother, the quiet nurse Cassan (Susan Kelechi Watson), who is the closest to Amber, to round out the backstory with Zambia’s questions. Zambia and peacemaker Clementine move along the arc of development which settles upon two issues. How will they pay off the tax liens against the house, and who inherits the quilts, (pricey relics which are cultural artifacts of a rich historical past), the property and the cabin contents?

These questions are answered as Hall unspools each sister’s interior wounds via their relationships, revealing their individual portrait of their complicated, intriguing mother. All clarifies and we are brought to the edge of unresolved personal traumas that threaten to further destroy their lives emotionally, physically, spiritually. However, it is the act of quilting together that we view the whole with the sisters contributing to the corners of the ancestral masterpiece that unifies them with a familial love and redemption from past harm effected by their mother, each other and most importantly themselves.

Mystical elements

Hall’s first act languishes in exposition until the conflicts among the sisters erupt. The details of the quilting process fascinate and are well integrated into the dialogue. The symbolism and metaphor of the stormy souls aligned with the threatening hurricane’s thunder and lightening effected by Jiyoun Chang (lighting design), Palmer Hefferan (sound design), and Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew (projections), mirror how the natural world, material world and spiritual world often collide until there is a movement toward establishing peace and reconciliation.

Blain-Cruz does a smashing job referencing the impact the spiritual plane of existence has upon the material life of the sisters which is sensationally wrought in Act 2 toward the conclusion when they attempt to place the finished quilt on their mother’s bed and a mystical experience occurs. It is then when Zambia becomes the channel between the past spiritual legacy and the present and the pathway toward healing is realized.

The costumes by Montana Lvi Blanco pointedly imbue each of the sisters and Zambia’s changing “trends,” enhancing Hall and Blain-Cruz’s vision of this family to precisely tie in their characters culturally and psychically. Importantly, the ensemble works together to create a family drama with which we can identify and empathize. Their acting is superb. Perhaps the Geechee deserves a translation either in the program or elsewhere. I was benefited by a copy of the script. Vitally, the different language serves to remind the audience of the African diaspora that beleaguered the Jernigan ancestors-slaves, and unified them as they prospered in a hostile, alien world.

The Blood Quilt

See The Blood Quilt, which runs two hours forty-five minutes with one intermission at LCT, the Mitzi E. Newhouse, until December 29th.

,

‘Tina-The Tina Turner Musical,’ The Astounding Power of Soul Transformation Gloriously Alive on Broadway

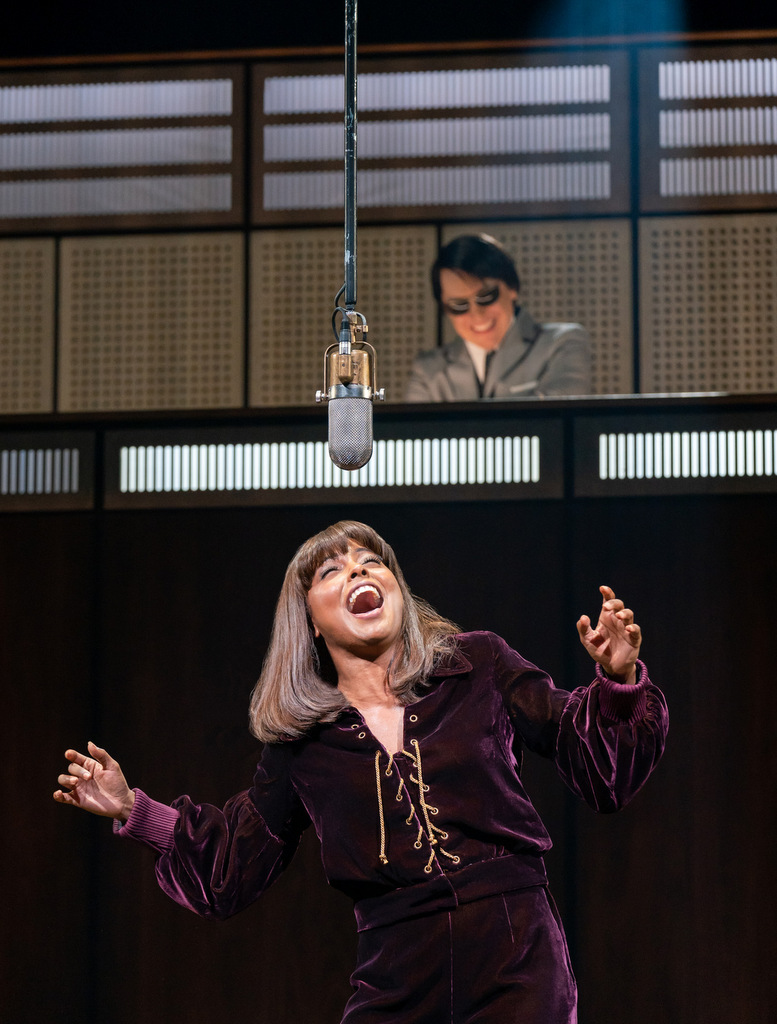

Adrienne Warren in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins, choreographer by Anthony Van Laast, set and costume designer Mark Thompson, musical supervision, arrngements, additional music and conductor Nicholas Skilbeck directed by Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

Tina-The Tina Turner Musical with equal parts magnificent entertainment, profound lessons on life, survivor’s tale, series of club performances and recording studio sets that recall the wonders of our musical past is just breathtaking. And that is before the final triumphant concert where Tina (the unparalleled Adrienne Warren), emerges in her glorious manifest destiny as the icon we’ve come to celebrate and adore.

The concert IS Tina! Directed by Phyllida Lloyd, choreographed by Anthony Van Laast, with musical supervision, arrangements, additional music by conductor Nicholas Skilbeck, Tina currently runs at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre.

The musical sends a heroic message that the impossible is possible. And it reveals how Tina Turner broke through the limitations of race, class, gender and the white male-dominated music industry with grit, determination and panache. Above all Tina is a measured, profound reveal at how connecting with one’s inner spiritual being can bring peace and love to uplift others to heal.

Writers Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins have written a stunning book of memory, beauty and emotional chronology, interlacing songs to illustrate the resonance of spiritual evolution in a human life. They’ve chosen to open Tina with Adrienne Warren as Tina chanting, “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” before a concert in Brazil, 1988. Chanting with her in consciousness (we discover later), is one who influenced her from her past, Gran Georgeanna (Myra Lucretia Taylor), who is part Cherokee Native. Emerging to bring her back to the past is a different spiritual influence, her father Richard (David Jennings), pastor of a small congregation in Tennessee.

These forces from her childhood which thread the spiritual elements throughout her life are included in the production. They symbolize the foundation of Anna Mae Bullock’s soul and ethos. Her transfiguration from Anna Mae to iconic solo performer Tina Turner is forged by the creative team of Tina with keys that open the doors to that revelation: Tina’s and Ike’s songs, Tina’s songs, and the design teams’ elucidation with historical musical references, symbols and themes reflected in the lighting, sets, screen projections, costumes, hair/wig/make-up designs. These elements thought out with painstaking care by the director and design team are magnificent reflectors of Tina Turner’s process of crafting a new identity.

Skye Dakota Turner, David Jennings, Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, Book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar, Kees Prins, directed by Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

Director Phyllida Lloyd’s staging of the opening, her choices and vision for this musical remain acute and profound. For example, not only does the first scene ground us in the importance of Tina’s life approach (Buddhist meditation), her face, symbolizing “self” and “being” is shielded from us. This brief scene sets up the overarching flashback which will answer the question: who is this woman sitting in a humble position as if at the bottom of a well, with lighted stairs leading upward to the distant audience waiting to see her perform?

As Tina connects to oneness in her meditation (Nichiren Buddhism), the chronicle of her past opens. The musical unspools an exploration of her persona that metamorphosed with wheel and woe to make its glorious impact on us today.

During her chanting, the character evokes the past from which she attempts to redeem herself (“Etherland-Song of Mystic Law”). We empathize with her journey toward ego manumission. A condition of the musical is that the writers of the book and Adrienne Warren’s performance as Anna Mae/Tina strike human truths with emotional authenticity and power.

Vital events in this process are structured as turning points. These are intensely heartfelt to reveal Tina’s physical, mental and emotional abuse. However, the pain informs the artistically rich through line of creation and that spurs her transfiguration toward wholeness. Thus, as we go back in time with her, we become fellow seekers. We receive the wisdom of how this particular sojourner traveled into soul darkness, came to the end of herself, survived and emerged to embrace light, love and life.

(L to R): Adrienne Warren, Myra Lucretia Taylor,Katori Hall, in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, Book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

From the outset Lloyd cleverly, carefully structures the musical’s chronological arc of Tina/Anna Mae’s spiritual development rendered painstakingly by Hall, Ketelaar and Prins. The musical is without narration eschewing what has come to typify some other “bio-theater musicals” that have been reduced, stereotyped and dismissed as “jukebox theater.” It would be folly to buzz-saw through Tina with such an opaque understanding. The musical is layered, the empathetic themes are instructive and the creative team’s efforts from ensemble acting to spectacle design manifest their greatness with prodigious ingenuity.

In the Act I flashback the scene shifts to a spare setting, with a symbolic, ancient-looking, gnarled tree of meagerness in Nutbush, Tennessee 1950, which reflects Anna Mae’s roots. We are at an unadorned church service that Young Anna Mae attends with her family as father Richard (the fine David Jennings), preaches. The choir/congregation sing (“Nutbush City Limits”). Then, it happens, a defining moment from which all the other events flow. Anna Mae, like Thespis (the first actor of Ancient Greek Choral Theater), emerges from the choir. Anointed by “The Holy Spirit,” with unrestrained passion, she sings, dances and gloriously ignites all in the church to worship and lift themselves out of the misery of their lives.

Dawnn Lewis in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, Book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

From the moment Young Anna Mae (the phenomenal Skye Dakota Turner whose golden singing can charm dragons), sings and dances, sparks of joy electrify us. Nevertheless, her judgmental mother Zelma (Dawnn Lewis gives a steely, spot-on performance), sits annoyed. Obviously, Young Anna Mae has a voice with destiny in its timber. Zelma’s selective hearing deigns that it’s “too loud,” and in the next scene at the dinner table she cruelly upbraids Anna Mae for her lying pretense, “acting” like she has a relationship with God! As Zelma raises her hand to slap Anna Mae, Richard physically intervenes.

Daniel J. Watts in , in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, Book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

We understand why the ongoing physical and verbal abuse from Richard drives off Zelma. But we empathize with Anna Mae especially when her mother, without explanation, takes only Alline (Mars Rucker), with her to St. Louis, and Richard abandons her to Gran Georgeanna. It is her grandmother who encourages her singing and spirituality with great love.

The scene shifts again and it is another turning point years later where Adrienne Warren as the teenage Anna Mae and Gran sing the poignant (“Don’t Turn Around”). Gran affirms Anna Mae must leave her hard scrabble life in Nutbush (she has three jobs one of which was picking cotton), to take advantage of God’s vocal gift. Regardless of Anna Mae’s protest, Gran sends her to live with Zelma and Alline, but the explanation we discover later is that dying Gran spares Anna Mae her loss. Yet, writers clarify throughout the production that in Anna Mae/Tina’s consciousness during crisis-filled moments, Gran is ever-present in spirit to strengthen her.

Adrienne Warren, Daniel J. Watts in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, Book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

Anna Mae embarks on her journey to greatness as Gran’s vision for her comes true. Despite her positive relationship with band member Raymond, (the attentive, sensitive Gerald Caesar), who tries to protect her from Ike (the incredible Daniel J. Watts), and with whom she has a child, (“Let’s Stay Together”), she marries Ike Turner. By then Ike has “christened” her his “Queen,” the “Tina Turner” of the Ike and Tina Turner Review.

The Ike and Tina segments meld the songs from Tina’s career with thoughtfulness. These enlighten us to the growing bondages in their relationship: (“Shake a Tailfeather,” “She Made My Blood Run Cold,” “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine,” A Fool in Love,” “Better Be Good To Me”). By then Ike is doing backup with his band The Kings of Rhythm. The Ikettes (the superb Holli Conway, Kayla Davion, Destinee Rea, Mars Rucker), are the movers and shakers with Tina in the lead. Additionally, Ike hires a sometime mistress Rhonda (Jessica Rush), to manage the group. As a duo Tina and Ike, R and B it to Rolling Stones Magazine’s #2, out of “Twenty Greatest Duos of All Time.”

(L to R): Adrienne Warren and the company of Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

The musical’s set design projections, lighting design, costumes, wig and hair design, orchestrations, musical supervision, arrangements, etc. are historically appropriate and inform the appearance and the sound of the Ike and Tina Review. The performances of the songs are signatures of the time and bring a superb reckoning of our American musical past, when the culture and society was burgeoning and roiling, and black artists were looking to move up in the music industry.

However, the cost that Anna Mae/Tina pays to manifest Gran’s vision is almost too great to bear during the years she and Ike are married, have one child together and raise her child with Raymond. Tina is the doll Ike fashions her to be. He controls every aspect of her life and intimidates her to put up with his adultery and drug use. To subordinate her and keep her close, he pays her no salary and micromanages what she does. He decides that after she has Craig (their child together), she cannot rest but must work in the studio to cut a record and stay up all hours. This erodes her health and well being.

Adrienne Warren, Steven Booth in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, Book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

Adrienne Warren’s Tina is emotionally riveting. Not only does she hit every nuanced feeling that we imagine Tina felt when she ended the relationship with Raymond (“Let’s Stay Together”), she also beautifully intuits Tina’s growing soul destruction through self-recrimination and despair. We note each time Tina allows Ike to abuse her mentally and emotionally. Warren reveals Tina’s emotional disintegration as he bullies Tina to subvert her personal choices into his “Tina Turner” wind-up puppet. We watch her lose dignity, confidence and self-worth. Even the “Tina” identity is wholly owned by Ike. Warren’s vocal resonance in her portrait of Tina struggling through the pain is bar none.

Because Tina cannot leave him and forsake her career, livelihood and her public identity, she stays through the intensifying physical abuse, despite warnings by Rhonda and the Ikettes who have become friends and try to “watch her back.” With every blow, every mercenary act she receives from Ike, Tina’s inner self withers battered by her own self-hatred for forgiving him and remaining silent. Warren’s uncanny performance reveals Tina’s inward progression into an abyss of despair.

(L to R): Adrienne Warren and the company of Tina-The Tina Turner Musical,’ book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

Because Daniel J. Watts’ portrayal as Ike is a striking, intensely human counterpart to Warren’s, we understand the dynamic of their relationship and why Tina doesn’t leave him the moment he throws a symbol at her. Watts has a difficult role as Ike in not making him the complete devil that the Ikettes attribute him to be. But Watts is not cardboard malevolent. He reveals Ike is one hot mess who is edgy and charming and at heart obsessed with music, Tina and what he has crafted “their star power” duo to be. Watts authenticates Ike’s great fear of losing Tina that converts to jealousy for as lead, she is the better performer and should leave him. On his knees he makes her promise to stay; of course, she does.

His insecure, fear-filled behavior augments after the wonderful music studio scene with Phil Spector (Steven Booth), who gets Tina to sing to the “god” in herself (“Deep River Mountain High”). Watts infuses Ike’s ambition, his wanting to “be someone” in life with underlying anger and sorrow. Ultimately, he is shaped by the vicissitudes of Southern bigotry, a lack of personal restraint and the music business’ penchant for exploiting artists or rendering them invisible. Like Warren’s, Watts’ portrayal is acute, authentic, empathetic. He especially reveals the nuances of Ike’s character in all of his scenes with Tina keeping them dynamic and menacing (thanks to the fight direction by Sordelet Inc.).

(L to R): Adrienne Warren and the company of Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

The musical’s action heightens organically with escalating emotional rawness as Ike’s and Tina’s relationship spirals downward during the last scenes of Act I. Warren’s singing becomes more frantic as she is manipulated and seduced by Watts’ Ike in their exceptional “Be Tender With Me Baby.” In the performance of the song we note the chains of fear, desolation, self-hatred, yet love of their mutual identity together. However, Tina is end stopped; there is no way for Ike to let her go and for her to leave. As a way out of self-loathing and stalemate, Tina takes 50 Valiums before going onstage. Ike’s comment, “Bitch, you die on me I’ma kill you,” is hysterical if it were also not tragic. The writers have fashioned her suicide attempt as a quick break, seguing into a short scene with her mother who, with sardonic encouragement, encourages her to stay with Ike and beat him (like she did former husband Richard), the next time Ike abuses her.

(L to R): Adrienne Warren in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

After her mother’s jarring, callous injunction (typical of the times), Tina’s frenzy increases to a visibly heartbreaking climax as she sings, “Proud Mary.” In Warren’s interpretation and vocal majesty the song becomes a metaphor for the overcoming power of Tina as “riverboat queen.” She is Proud Mary! She will “keep on burnin,” “keep on turnin,” and “keep on being proud,” not for Ike, but for herself. And when she keeps on “rollin’ down the river” of life, it will be as a whole person, spirit, soul, body. As Warren stops the concert and leaves the stage, to stand up to Watt’s Ike, matching his blows, we know she’s come to the end of herself. Hall and the others state in the stage directions, “this is her Garden of Gethsemane.” No one but she can act for herself. Alone, she must confront her inner hell and be courageous enough to leave it.

Like a slave seeking freedom, in a symbolic, iconic scene, Warren’s Tina runs out of the concert hall and across a highway (effected by screen projections and sounds of horns blaring and lights and music from the past), to arrive at a roadside hotel, bruised, bleeding, dark hair in disarray, dressed in just a slip. A shaking Adrienne Warren imbues Tina’s emotions of hope, fear, sadness, desperation as she reaches out to receive the room key from the night manager (hand stretched toward the audience). The key is symbolic of freedom and with it she unlocks the door which opens into a new ethos which only she can forge with the help of hovering spiritual ancestors, hope, Buddhism and more.

Poignantly, as Warren sings with the ensemble, “I don’t Wanna Fight No More,” she sings to herself, and her past (represented when the characters of Gran, Young Anna Mae and others minister to her and clean her up). With the flash-forward to the present she is in meditation back where we began in Brazil 1988 as Act I ends where it began. Just incredible.

Adrienne Warren in Tina-The Tina Turner Musical, book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins, choreographer by Anthony Van Laast, set and costume designer Mark Thompson, musical supervision, arrngements, additional music and conductor Nicholas Skilbeck directed by Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

Act II chronicles how Tina uses her freedom, extracting herself from Ike’s power litigating only for her name and at Rhonda’s suggestion, establishing the new “Tina.” The second act is equally thrilling as Tina’s lotus bud rises from the mud to shine its beauty becoming the lion-maned Tina adored globally. Helping along the way are Australian Roger Davies (Charlie Franklin), who becomes her manager and shepherds her toward a new sound, Rock and Roll with crossover appeal to white audiences, which she chooses to sing, and a new look she effects for herself.

But she must continually meditate and throw off her past and Ike who haunts her in her lonely sadness (“I Can’t Stand the Rain”), which Lloyd directs as an evocative scene of the lonely London landscape replete with umbrellas and screen projections. A romantic answer to loneliness is Erwin Bach (Ross Lekites), with whom she eventually ends with as partners. Ever-present are Gran and even visions of the anointed Young Anna Mae who encourage her before and after Capital Records hears her London showcase and rejects her until she sings “What’s Love Got to Do With It” at the Ritz in New York City, 1983.

With Davies, Tina establishes she is the boss and not a puppet. This is reinforced with Ike, a point clarified after her stunning success and before the concert when she mails back a doll he sends her in an attempt at forgiveness. In a final scene between Tina, Ike and Zelma who is in the hospital, though Ike attempts to apologize in a written letter, he cannot say it “to her face” and leaves with silence on his lips. But Zelma makes amends apologizing that she could never be the mother to Tina that she should have been. We empathize with Zelma’s explanation: Tina was like holding “fire,” and “fire illuminates your own flaws,” and of course, fire burns. In saying goodbye to the pain, hurt and abuse from their past, Tina and Zelma sing (“Don’t Turn Around” reprise). Tina is finally able to move on and climb the steps to perform for the nearly 200,000 waiting fans in Brazil, 1988.

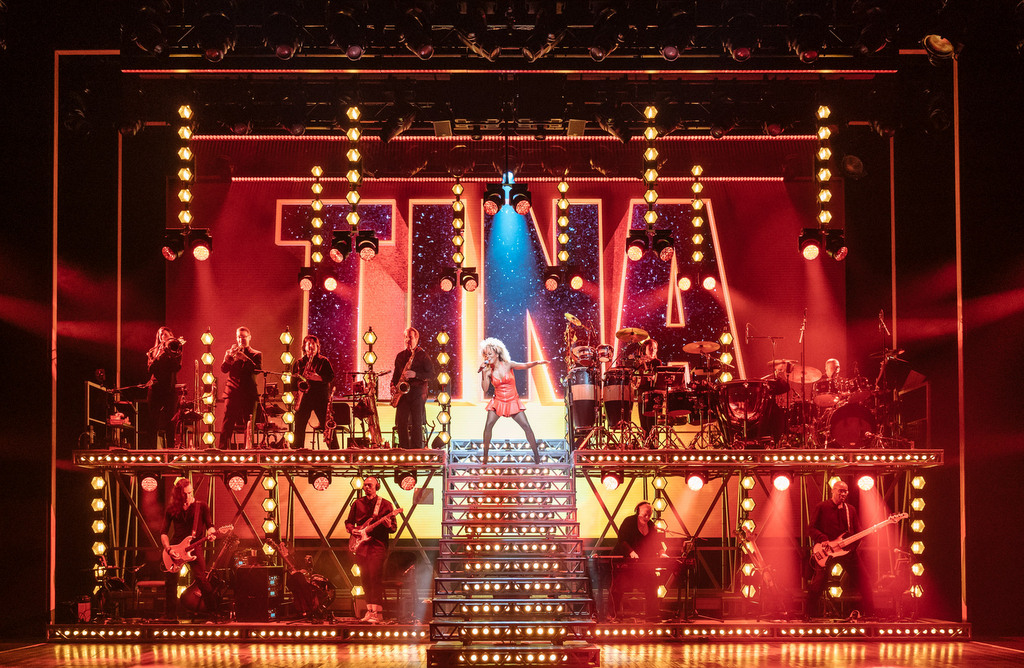

Adrienne Warren and the company of Tina-The Tina Turner Musical,’ book by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins directed by, Phyllida Lloyd (Manuel Harlan)

The concert in which the set revolves and Tina manifests the bright light of transformation, Warren effects relaxed confidence as she “lets go and lets God,” coming down the stairs to welcome us, her concert audience. As Warren sings/dances with the company, “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” “Simply The Best,” and “Proud Mary,” she is the spectacular Tina Turner. She sings in dazzling array with lion mane and shimmery costume. The regal stage, her platform to shine, sparkles. The metaphor of the steps (i.e. a Jacob’s Ladder), which she ascends and descends reflects that she is the messenger of joy to emotionally uplift her fans. The lighted stairs may also symbolize how she has traveled “up from slavery,” up from the abyss and down into her settled spirituality and wholeness assured of bringing her gift of love to her audience. Realizing that every detail of her past cements her current greatness, one cannot help but divine that she spiritually has been influenced to this destiny to encourage us to “keep on burnin,” and “rollin on the river,” with verve, in celebration of our lives.

Tina will be an award winner. The book is sensational as is the stellar performance by Warren which deserves its own created category. Watts’ portrayal is outstanding and the ensemble is first-rate. Finally, kudos go to Anthony Van Laast (choreographer), Mark Thompson (set and costume designer), Nicholas Skilbek (musical supervision, arrangements, additional music and conductor), Ethan Popp (orchestrations), Bruno Poet (lighting design), Nevin Steinberg (sound design), Jeff Sugg (projection design), Campbell Young Associates (wig, hair and makeup design), John Miller (music coordinator). All serve the director’s vision and enhance the musical beyond expectation.

Tina-The Tina Turner Musical runs with one intermission at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre (205 West 46th). For tickets and times CLICK HERE.