Blog Archives

‘Liberation’ Transfers to Broadway Solidifying its Excellence

Bess Wohl’s Liberation directed by Whitey White in its transfer to Broadway’s James Earl Jones Theater until January 11th doesn’t add references to the 2024 election nor the disastrous aftermath. However, the production is more striking than ever in light of current events. It reaffirms how far we must go and what subtle influences may continue to derail the ratified ERA (Equal Rights Amendment) from becoming settled law.

To draw parallels between the women’s movement then and now, Wohl highlights the “liberation” of the main character/narrator Lizzie, an everywoman, with whom we delightfully identify. With Lizzie (the superb Susannah Flood) we travel along a humorous journey of memory and self-reflection as she evaluates her relationship to her activist mom, who gathered with a community of women in Ohio, 1970 to “change the world and themselves.”

Wohl’s unreliable, funny narrator, directs the action and also is a part of it. The playwright’s smart selection of Lizzie as a device, the way in to tell this elucidating story about women evolving their attitudes, captures our interest because it is immediate. Her understanding is ours, her revelations are ours, her “liberation” is also ours. Lizzie shifts back and forth in time from the present to 1970-73, and back to the present. One of the questions she explores concerns why the women’s movement cascaded into the failures of the present?

Assuming the role of her mother, Lizzie enacts how her mom established a consciousness-raising group. Such groups trended throughout the country to establish community and encourage women’s empowerment. Six women regularly meet in the basement basketball court at the local rec center which serves as the set throughout Liberation, thanks to David Zinn’s finely wrought stage design. The group, perfectly dressed in period appropriate costumes by Qween Jean, includes a Black woman, Celeste (Krisolyn Lloyd), and the older, married Margie (Betsy Aidem).

Having verified stories with her mom (now deceased), and the still-living members of the group, Lizzie imagines after introductions that the women expansively acknowledge their hope to change society and stand up to the patriarchy. As weeks pass they clarify their own personal obstacles and their long, bumpy road to change, with ironic surprises and setbacks.

For example, Margie voices her deeper feelings about being a slavish housewife and mother. After months of prodding, her husband actually does the dishes, a “female” chore. Margie realizes not only does she complete housework faster and better than he, but her role as housewife and nurturer satisfies, comforts and makes her happy. Betsy Aidem is superb as the humorous older member, who introduces herself by announcing she joined, so she wouldn’t stab her retired husband to death.

Some members, like Sicilian-accented Isidora (Irene Sofia Lucio), and Lloyd’s Celeste, belonged to other activist groups (e.g. SNCC). Circumstances brought them to Ohio. Isidora’s green-card marriage needs six more months and a no-fault divorce, not possible in Ohio. Celeste, a New Yorker, has moved to the Midwest to take care of her sickly mom. The role of caretaker, dumped on her by uncaring siblings, tries her patience and stresses her out. Expressing her feelings in the group strengthens her.

Susan (Adina Verson) is an activist burnt out on “women’s liberation.” Frustrated, Susan has nothing to say beyond “women are human beings.” She avers that if men don’t treat women with equality and respect, then women’s activism is like “shitting in the wind.”

Lizzie and Dora (Audrey Corsa) discuss how they suffer discrimination at their jobs. Despite her skill and knowledge Lizzie’s editor demeans her with “female” assignments (weddings, obituaries). Dora’s boss promotes men less qualified and experienced than Dora. Through inference, the playwright reminds us of women’s lack of substantial progress in the work force. Very few women break through “glass ceilings” to become CEOs or achieve equal pay.

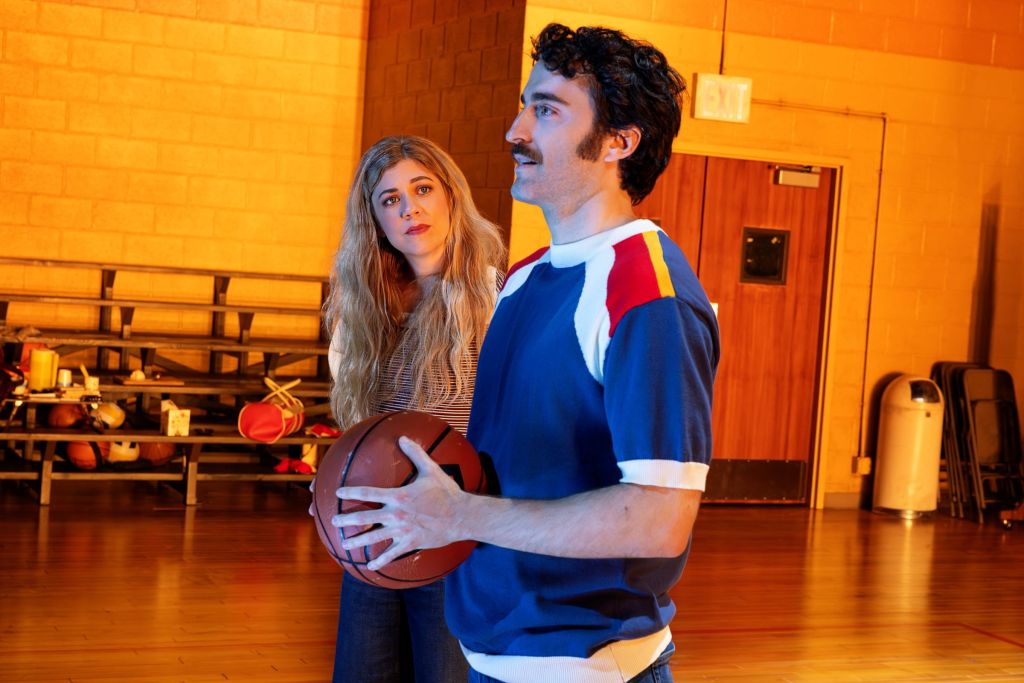

Act I engages because of the authentic performances and various clarifications. For example, Black women have a doubly difficult time at overturning the patriarchy. Surprisingly, at the end of the act a man invades their space and begins shooting hoops. Is this cognitive dissonance on Lizzie’s part for including him? Have women so internalized male superiority that they become misdirected back to the societal default position of subservience? Is this what thwarted the movement?

When Lizzie refers to the guy as Bill, her father (Charlie Thurston), we get the irony. How “freeing” that her mom meets her dad as she advocates for liberation from male domination, only to be dominated by an institution (marriage) constructed precisely for that purpose.

Act II opens with additional dissonance. To extricate themselves from the psychological trauma of men’s objectification of their bodies, the women free themselves from their clothes. Sitting in the nude, each discusses what they like and dislike about their bodies. The scene enlivened heterosexual men in the audience, an ironic reinforcement of objectification. We understand that these activists try to overcome body shame that our commercial culture and men use to manipulate women against themselves and each other (surgical enhancements, fillers, face lifts, etc.). On the other hand the scene leaves a whiff of “gimmick” in the air, though Whitney White directs it cleverly.

After the nude scene Lizzie reimagines how her mom and Bill fell in love. To avoid discomfort in “being” with her father, she engages Joanne (Kayla Davion), a mother who drops into the rec room looking for her kids’ backpacks. Through Bill and Joanne’s interaction, we note the relationship that Lizzie keeps secret. When Lizzie finally reveals she is engaged, the dam bursts and each of the women reveals how they have been compromising their staunch feminist position. One even admits to voting for Nixon with a barrage of lame excuses.

This scene is a turning point that Lizzie uses to explore how women in the movement may have sabotaged themselves at advancing their rights. Reviewing her mother’s choice to get married and co-exist as a feminist and wife, Lizzie reimagines a conversation with her deceased mother played by Aidem’s Margie in an effecting performance. When Lizzie asks about her mom’s happiness, Margie kindly states that Lizzie has gotten much of her story wrong.

Lizzie condemns feminism’s failures. This is the patriarchy, internalized by Lizzie, speaking through her. With clarity through Margie’s perspective, Wohl reminds us that all the stages of the feminist movement have brought successes we must remember to acknowledge.

Lizzie realizes the answer to whether one might be “liberated” and fall in love and “live equitably” within an institution which consigns women to compromise their autonomy. It depends upon each individual to make her own way. Her investigation about her mother’s consciousness-raising group establishes the first steps along a journey toward “liberation,” that she and the others will continue for the rest of their lives.

Liberation runs 2 hours, 30 minutes with one intermission at the James Earl Jones Theater through Jan. 11th. liberationbway.com