Blog Archives

Theresa Rebeck, Presented by League of Professional Theatre Women at NYPL for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center

Theresa Rebeck. If the name doesn’t sound immediately familiar, chances are you do know Theresa Rebeck’s work from Broadway, off-Broadway, television, films or literature. A prolific writer, she is the most produced female playwright of her generation. Her work is presented throughout the United States and internationally. Her Broadway credits include I Need That (starring Danny DeVito), Bernhardt/Hamlet (starring Janet McTeer), Dead Accounts (starring Norbert Leo Butz), Seminar (starring Alan Rickman), and Mauritius (starring F. Murray Abraham). Her off-Broadway productions are numerous.

It was a pleasure to hear and see her live in an event sponsored by the League of Professional Theatre Women, Monday, June 3, 2024 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center’s Bruno Walter Auditorium. Interviewed by her close friend and producer Robyn Goodman (Avenue Q-Tony Award 2004, In the Heights-Tony Award 2008), Robyn founded Aged In Wood Productions in 2000. Their discussion was taped and is part of LPTW’s Oral History Project to preserve visual records of interviews of august women in the theater. The event was produced by director and producer Ludovica Villar-Hauser. A video of the event can be found in the Library’s TOFT Archive.

For the members of LPTW, Theresa Rebeck needed no introduction. Robyn Goodman began by asking general questions about Rebeck’s early life, and her background tie-ins to themes which often arise in her plays. This brief post focuses on a few salient highlights of the interview.

Born in Ohio, Rebeck grew up in an “ultra Republican, ultra Catholic” world. Receiving a Catholic education throughout, she graduated from Ursuline Academy in 1976 and continued with her Catholic education, graduating from the University of Notre Dame in 1980.

With irony and humor, Rebeck confided, “My parents didn’t want me to go to any East Coast School because they were afraid I’d lose my faith.” She shared that as a child, at times she went on a bus to see theater productions. Even at a young age, she venerated playwrights, thinking them gods. To her, Shakespeare, Moliere, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams were fantastic. She joked that she was already into theater and drama before she got out of grade school.

After Rebeck began acting in earnest at Ursuline Academy, she told her mother “I think I want to be a playwright.” Rebeck got laughs when she joked about her mother’s response, “She turned grey.”

Interestingly, during her freshman year at Notre Dame, Rebeck was invited to a very religious group who was holding a prayer meeting. It was “really spooky,” and the people were “really religious.” Rebeck sensed something “dark and weird going on.” They were speaking in tongues and talking about women being subservient so that everyone “should know their place.” She quipped, “After ten minutes I wanted to go back to my dorm room.” However, she wasn’t sure how to get back.

This was an introduction to members of “People of Praise,” the religious community Supreme Court Justice Amy Cony Barrett has been a member of since birth. “People of Praise,” is associated with the Catholic charismatic renewal movement, but is not formally affiliated with the Catholic Church. Rebeck’s experience at the prayer meeting and listening to the group’s tenets sent her fleeing in the opposite direction. “People of Praise” appears to be unrepresentative of Rebeck’s Catholic upbringing which has well served her life and work.

As a tie-in, Robyn Goodman read a quote from the award-winning playwright Tina Howe (Coastal Disturbances, Pride’s Crossing), who died last year at 85-years old. Howe said of Rebeck that her “Catholic upbringing has had a profound imprint on her work,” and there’s “a moral heart to Theresa.” According to Howe, “She’s a force of nature who always carries her altar with her.”

When Robyn Goodman asked Theresa, “Do you see this in your work?” She responded, “I do.” Rebeck then grounded the history of theater with the idea of faith as an inherent meld. She claimed she is “one of those people” who thinks that the theater is “holy territory.” And she says of herself, “I’m always a person that points out that theater was a religious ceremony.”

In ancient civilizations the dance and tribal ritual and ceremonial presentation had a deep spiritual and religious basis. With the Greeks who allowed even the slaves to take off from work to participate, theater was a celebration of the god Dionysus, and there were annual play festivals and competitions. Rebeck suggested that in various cultures, there was the shaman or priest, and sitting right next to him was the playwright. For Rebeck, “The gathering of people to share stories and identify with the stories is powerful.”

In responding to Robyn Goodman’s question about her transformation to professional theater, Rebeck mentioned her first production was Spike Heels (1993), that Goodman produced at Second Stage Theater. It starred Kevin Bacon, Tony Goldwyn, Saundra Santiago and the great Julie White. “My husband was in it,” quipped Rebeck. Theresa is married to Jess Lynn, and together they have two children.

Goodman asked if the production and notoriety changed her life, especially the good reviews. Rebeck suggests that with the critics peppering her with questions, “It was like watching all the senators grilling Anita Hill.” One of the questions they asked, was, “Are you going to write a book?” Frank Rich compared Spike Heels to the film Pillow Talk. According to Rich, Kevin Bacon was Gig Young, etc.

Four months later, David Mamet’s Oleanna, which premiered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, appeared off- Broadway at the Orpheum Theater. Frank Rich reviewed it and Rebeck noted Rich’s review. He commented that after the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas fiasco on Capitol Hill, “finally someone wrote a play about sexual harassment.” Rebeck’s response was tellingly frustrated. She shared her feelings about his comment. “Hey! You saw a play about sexual harassment written by a women and you didn’t notice.”

It was “a different time,” Rebeck said, as she discussed how she reacted to the male/female power issues. “You go along with it, get mad when you go home and try to discuss it, and you’re incoherent.” With Rich’s comment about Oleanna, Rebeck says,”I thought, ‘Come on, this isn’t about sexual harassment. This is a women lying about sexual harassment.'” Rebeck affirmed with Goodman that women were fighting for their place and stature at the time, so it was “very important to produce plays like that.” Rebeck suggested, “I was way ahead of my time,” which received an appropriate laugh.

Goodman pointed out another quote about Rebeck’s writing in that she often writes about “betrayal, treason and poor behavior, a lot of poor behavior.” To that Theresa agreed that many playwrights write about “poor behavior.” Goodman added that Rebeck also writes about class and power shifts.

Rebeck discussed her experiences with productions on Broadway and off-Broadway. In fact, she suggested that she began directing because after the effort and time spent writing a play, she got tired of the release process, after her initial involvement with the production. She went to the table reads, heard design presentations and answered questions people asked. Then came the “thank yous” and she would leave. Rebeck didn’t want to be at the side of “the main event.” She wanted total involvement.

She enjoyed working on Dig, which she also directed and which received wonderful reviews. “I’m so proud of it. It was a good experience.” It is important to Rebeck that the creators have work that they can claim as their own. She enjoys working collaboratively when people are respectful.

Goodman and Rebeck appear to have a shared view of how people negotiate successfully in the “real world.” They negotiate with a sense of morality. Goodman shared the quote which political parties, especially the Trump MAGA Party, eschew as anathema. “If you make the truth your friend, it can’t come and eat you alive.” Rebeck and Goodman agree that a clear, moral point of view in plays, musicals and literature is vital.

Theresa suggested that her alma mater Brandeis University also grounded her toward presenting a clear, moral point of view in her work. She received her three graduate degrees from Brandeis: her MA in English in 1983, a MFA in Playwriting in 1986, and a PhD in Victorian era melodrama in 1989. Fittingly, Rebeck pointed out, that on the seal of Brandeis University are the words, “Truth even unto its innermost parts.” The university president decided to surround the shield on the seal with the quote about truth which is from Psalm 51. Rebeck noted that she recognized the seal on the podium (though it wasn’t clear at that point that it was Brandeis), hearing/seeing a clip of Ken Burns deliver his trenchant Keynote Address to Brandeis University’s 2024 undergraduate class during the 73rd Commencement Exercises. If you haven’t heard any of his speech, you can find it on YouTube. It is definitive and acute.

Rebeck affirms that “writing plays is about people” in the hope to understand “human brilliance and failure.” Of course at times there’s “political content.” However, at the heart it’s about people and human behavior.

In responding to Goodman’s question related to critics, Rebeck agreed that sometimes reviews are devastating and that her husband goes through the process with her. She mentioned that there can be five wonderful or enlightening critiques, and then there is the “crazy” review which is off kilter and seemingly out of nowhere, and people are “foaming at the mouth.” Sometimes, there is that one review while other critics and audiences love the work.

At one point Rebeck thought, “Why do they hate me?” Then, she realized if there’s one outlier, then there isn’t coherence. She mentioned that for a long time people only cared about and quoted the “paper of record.” Of course the irony was that there were many different critics and opinions. The diverse voices and viewpoints are exciting and especially vital for our time. That one opinion held sway and could make or break a play was “damaging to the psyche of the community.” She affirmed, “Now, it’s less dire.”

Rebeck spoke of an incident with a young producer who acted as if there was only one paper that mattered, historically, the “paper of record.” This individual said, based on one review, “Well, the reviews were bad.” Rebeck gave them a reality check. She said that a producer should never act like there is one reviewer who speaks for all critics. To obsess about one review is to bury oneself in negativity and recriminations. She told the producer, “Don’t do that!”

Indeed, Rebeck’s point is well taken. Historically, other critics bought into the prestige factor of “the paper of record,” denigrating their own voices and viewpoints, and bowing to the one review that allegedly spoke for all critics. In this day of book bannings, culture wars and rewriting history, such an approach is tantamount to critics mentally censoring themselves as inferiors. If there is a consensus about a play, that speaks volumes. One “determination” by one critic, regardless of how much he or she is paid, shouldn’t be the “word from on high” that the critics, theater professionals or the public “should” listen to and take to heart.

Rebeck and Goodman are expanding their winning teamwork. They’ve joined together on the musical Working Girl, based on the titular1988 Twentieth Century Fox motion picture written by Kevin Wade. Aimed for Broadway, the musical is presented by special arrangement with Buena Vista Theatrical. Writing the book, Rebeck discussed how she loves working with Tony-winning, composer-lyricist Cyndi Lauper (Kinky Boots), who is writing the score. Tony winner Christopher Ashley (Come From Away) is directing. Producers include Goodman and Josh Fiedler of Aged in Wood Productions, and Kumiko Yoshii.

Rebeck created Smash for NBC and briefly discussed a few highs and lows of working on the showbiz dramatic series. She liked Stephen Spielberg. Since Smash, she has been especially enamored of musical theater. Working Girl is a project that involves collaboration. To have to write a play singularly and then give it to a composer and lyricist is something Rebeck wasn’t interested in doing. She and the team are reimagining and updating the classic. It’s an exciting approach because it also emphasizes women working together and supporting each other on their “climb to the top.” With the political climate as it is, the musical is profoundly important.

One of the themes of the evening was that especially after COVID-19, theater has changed. Theaters around the country are in deep financial trouble. Robyn Goodman suggested that Broadway has gotten out of hand. The business is completely different than what it was two decades ago. Now, to mount a production viably, it costs $25 million dollars. It’s all about the money and finding backers.

As for budding playwrights, Rebeck advised that festivals are a good venue as a place to begin and get noticed. Indeed, 10 minute play festivals allow the creative team to put on “a beautiful event” for little or no money. One can even write a short one-act play and submit it to a one-act play festival. This is a boon for the playwright, who needs to learn how the process works and see the audience’s response to the play. That is an imperative for beginning playwrights.

Rebeck’s plays are published by Smith and Kraus as Theresa Rebeck: Complete Plays, Volumes I, II, III, IV and V. Acting editions are available from Samuel French or Playscripts. For a complete listing of all of her work you can find Theresa Rebeck on her website: https://www.theresarebeck.com/ Robyn Goodman’s website is https://www.agedinwood.com/about

Visit The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, the Library’s TOFT Archive to see the digital recording of the evening. For more information about the TOFT Archives, see this link. https://www.nypl.org/locations/lpa/theatre-film-and-tape-archive To learn more about LPTW, check out their website. https://www.theatrewomen.org/

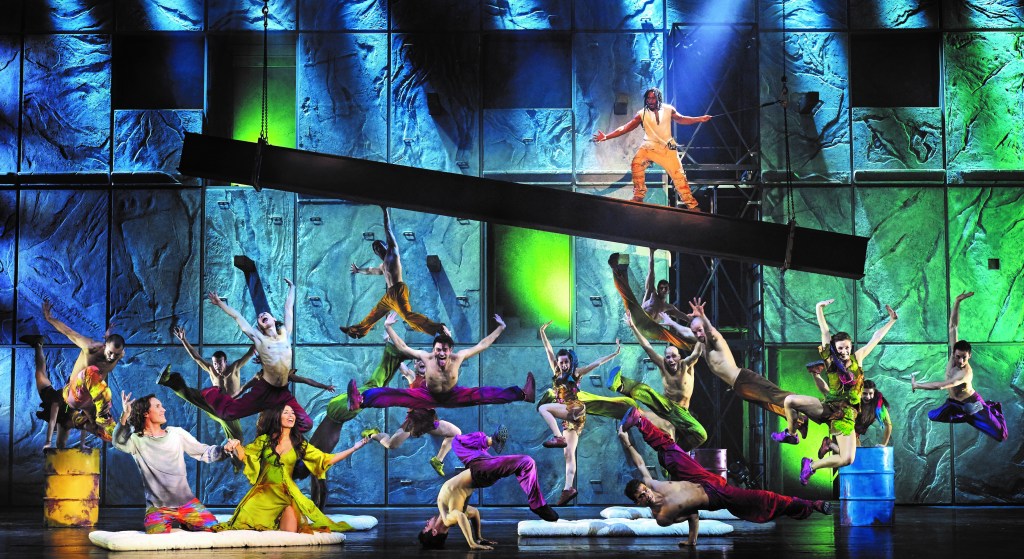

‘Notre Dame de Paris’ at Lincoln Center is Just Smashing!

For the first time in its twenty-four year history since its premiere in Paris, France in 1998, Notre Dame de Paris makes its New York City debut. The acclaimed musical spectacular has toured internationally, featuring successful productions in Canada, Italy, Lebanon, Singapore, Japan, Turkey and China. Performed in 23 countries and translated into nine languages, accumulating an enthusiastic 15 million spectators worldwide, the production at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center premiered on the 13th of July and runs through, Sunday, 24 July.

Notre Dame de Paris extravagantly directed by Gilles Maheu is a transcendent, opera-styled musical rendering of Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Based on Hugo’s monumental work of passion, love, lust, jealousy, cultural transformation, racism, classism and misogyny, the Notre Dame cathedral is the centerpiece around which most of the whirling action of this spectacle takes place.

It is there in front of the massive stones being set in the opening scene, Gingoire (the exceptional Gian Marco Schiaretti), introduces the cathedral in “Le Temps des cathedrals.” In the square in front of Notre Dame we meet the stratified economic classes of Paris, i.e. the undocumented immigrants who seek asylum and sleep in front of the cathedral. It is from there that the action leads out to the streets of Paris, beyond and back again. Thus, throughout, the cathedral becomes a moral, spiritual, ironic presence. It signifies a religion that encourages brotherly/sisterly love but rarely lives up to its aspirations in the actions of the clerics and the classist citizenry we meet.

Luc Plamondon’s lyrics propel the arc of development in composer Richard Cocciante’s sung-through, pop-rock, people’s opera. Generally, the almost three hour production follows Hugo’s novel, omitting minor characters that lightly impact the plot of the original work.

Cocciante’s florid music and Plamondon’s pop-rock lyrics comprise a total of 51 separate songs. Many of these are lyrical ballads describing the principal characters’ feelings about the situations they find themselves in. Others are powerful anthems, like the gorgeous signature song “La Temps des cathedrals,” and “Florence,” when Frollo and Gingoire discuss how Gutenberg’s printing press and Luther’s 95 Thesis will kill the old Paris and the cathedral as they make way for the new in the roiling undercurrents of society, as immigrants flood the city bringing with them new trends and transformations as they swell the population of Paris.

Live musicians accompany pre-recorded tracks performed in French with English surtitles provided on two screens to the left and right of the stage. Unlike opera the performers’ voices are electronically enhanced. At times one focuses more on sound than the quality of the performance. But all the principals have gorgeous voices and their talents are memorable and exquisite for this amazing, iconic musical epic.

There are seven principal characters who represent the inner and outer circles of the populace. These include Gingoire the poet and narrator who codifies the settings around Paris and introduces the characters and situations. Gingoire is the herald who announces the shifts in action. He moves among the Parisians and is a friend of those who have status like Frollo the Archdeacon of Notre Dame (the superb Daniel Lavoie). Floating among the undocumented immigrants Gingoire gets to know Clopin and Esmeralda in Act I, proving he is no respecter of classes and persons. In Act II he informs Clopin (Jay), the leader of the undocumented immigrants, that Esmeralda is in prison. Gringoire is present to understand how the immigrants try to come to Esmeralda’s aid to no avail. Her gender, her striking beauty, her class and above all her destiny, damns her.

In his movements around the city when Gringoire stumbles into the wretched Court of Miracles, it is then he becomes acquainted with Clopin (Jay) and Esmeralda (Hiba Tawaji). Situated outside the city walls, the ironically named court is the den of the impoverished undocumented, and the city’s outcasts. Clopin has created his own set of rules for the Court of Miracles that those who live there must follow. Kindly, he protects teenager Esmeralda allowing her to take refuge in the Court. Like a brother, he warns her against being too trusting of men.

Emeralda, a Bohemian from Spain is the catalyst who moves the action and emblazons the passions of men to love, hate or exploit her. As she prettily dances in the square, she unfortunately attracts the attention of the men of power, Archdeacon Frollo and Phoebus (Yvan Pedneault), captain of the King’s cavalry. They both want her. She becomes the vulnerable pawn who they attempt to exploit, abuse, then expediently toss away. Her youth, innocence and beauty are the fatal instruments that contribute to effecting her demise as the men wantonly pursue her sexual affections. The only one whose love she returns is Phoebus. However, he is pledged to marry a woman of consequence and class, Fleur-de-Lys (Emma Lépine). Eventually, he chooses a life of unhappiness with Fleur-de Lys because it is one which satisfies his need for stature and security though it is empty of love and pleasure.

Quasimodo, the lame, hunchback bell ringer also notes Esmeralda’s beauty and unhappily contrasts himself with her. She is someone he wishes to love but he knows it would be an impossibility. To confirm his “celebrity” as the most externally loathsome of all creatures, he is crowned “The King of Fools” in the songs “La Fête des fous” and “Le Pape des fous.”

Staged as frenetic, wildly antic numbers that involve the large cast, we watch as five acrobats, two breakers, and sixteen dancers, all of them marvelously talented, hurl themselves across the stage, spin and gyrate. These two numbers are visually exciting as most of the songs which combine dance are. Importantly, they create empathy, revealing how Quasimodo is treated by a world that worships physical loveliness and eschews deformity. However, Esmeralda has a kind heart and wishes that all humanity could become like brothers/sisters with no boundaries. She makes a connection of consciousness with him. Quasimodo becomes Esmeralda’s chief protector after she gives him a drink during his punishment for attempting to kidnap her on Frollo’s orders.

Quasimodo is Frollo’s puppet, having been raised by the cleric when he was orphaned as a baby. Whatever Frollo says to do he does because he is indebted to him. In the powerful and beautiful “Belle,” Frollo, Quasimodo and Phoebus secretly reveal their love of Esmeralda, claiming her for themselves. However, only Quasimodo loves her unselfishly without seeking to take anything from her, unlike Frollo and Phoebus.

The conflict intensifies when Frollo, unable to deal with his unholy, sexual feelings for Esmeralda attempts to take her for himself in an act of self-destruction and sinfulness, “Tu vas me détruire.” He has her falsely arrested for killing Phoebus, a lie. He knows she loves Phoebus and his jealousy enrages and victimizes him. His desire for her turns to hatred. Frollo visits her in jail where he propositions her to give herself to him and reclaim her life. Frollo has given up his identity and holiness embracing the hypocrisy of his lust and murderous jealousy of Phoebus. He is Archdeacon only in his robes and title. For her part Esmeralda realizes she fulfills her destiny loving Phoebus and sacrificing her life.

Daniel Lavoie who originated the role of Frollo masterfully reveals the character’s self torment, rage and incredible hurt, throwing off any mantel of faith to possess Esmeralda. In his portrayal Lavoie reveals Frollo’s doom as he blasphemes his religion, all in the shadows of Notre Dame. Though Quasimodo realizes Frollo’s malevolence and impulse to hang Esmeralda, there is little he can do to stop Frollo’s actions. Only after she hangs does he answer Frollo’s wickedness.

Notre Dame de Paris is a fitting title for this incredible production. The cathedral represents the chief moral and structural backdrop of the themes, characters and conflicts that reveal how religion, unless lived spiritually is a damnation. Also, it is upon this backdrop that we understand how fate and destiny unravel for Esmeralda, Frollo, Quasimodo and Phoebus, as they struggle to find but ultimately lose their place in the dynamically changing Paris of 1482.

This version is incredibly current in its attention to the plight of the undocumented immigrants, a situation that will only worsen globally with climate change and Putin’s War in Ukraine. Also, the production reveals the plight of women in the hands of men who have the power to abuse and destroy them. Hugo’s attention to humanity and the incompetence of religion to deny decency and hope to individuals who are stateless, classless and viewed by citizens as lower than worms is all the more striking because the situation still abides. One asks the question does anything change except the progress of science and technology when it delivers monetarily? Only the gargoyles can answer. Since this production was first mounted in 1998, progress reveals how much our humanity has deteriorated and even the cathedral itself has suffered a cataclysm that will never return it to its former ancient glory.

Kudos to the the director Gilles Maheu whose vision was faithfully melded in the staging, choreography by Martino Müller, set design by Christian Rätz, costume design by Caroline Van Assche, lighting design by Alain Lortie and hair and wig design by Sébastien Quinet. Praise also goes to musical director Matthew Brind and surtitles by Jeremy Sams. The production takes one’s breath away and every song is exceptionally beautiful in French and poetically lyrical if one understands the language.

Though Notre Dame de Paris has finished its New York City run you may catch it elsewhere as it is on tour and heading to Canada. Check out their various websites: https://nac-cna.ca/en/event/20729 http://www.avenircentre.com/ and look for it to return to the U.S. and perhaps New York City in the future.

23rd New York Jewish Film Festival Opening Night Film, ‘Friends From France’

L to R: Jeremie Lippmann and Soko in Friends From France, Les Interdits, Opening Night at the 23rd NY Jewish Film Festival, Lincoln Center

Opening Night of the 23rd annual New York Jewish Film Festival screened Friends from France (Les Interdits), written and directed by husband and wife team Anne Weil and Philippe Kotlarski. This was the U.S. premiere of the film which stars Soko, French singer and actress who most recently played the voice of Isabella in the film Her with Joaquin Phoenix. Weil and Kotlarski were present for a Q & A after the film. They clarified elements of characterization and choices they made with the film’s direction, discussing why they steered the film away from being solely political. They chose to make it more of a suspenseful, personal drama with political undertones as a backdrop for creating the film’s tense, thrilling atmosphere.

Friends from France is set at the height of the Cold War in 1979 Odessa when Soviet Jews were seeking asylum in Israel and America to escape the repression under the Brezhnev regime. The writers/directors achieve a chilling simulacrum of the oppressive environment the Jewish “refuseniks” and political asylum seekers confronted. With dark shadowy shots, washed out, grainy film, and hues of grey and bleeded out color, the predominantly nighttime action and cinematography reflects the impoverished settings, indicative of the lifestyle of the refuseniks who wanted to immigrate to Israel and were treated as enemies of the state. Filmmakers went to abandoned areas of East Germany to recreate the interior apartments and ramshackle dwellings as sets for the poor and rundown areas of Odessa where refuseniks lived in a world separate from the luxurious hotels, dachas, cafes, and restaurants enjoyed by those hooked into the communist party.

The film focuses on the relationship of nineteen-year-old idealist, Carole (Soko in a powerful performance) and Jérôme (Jérémie Lippmann) who are cousins on a mission that in their naiveté they don’t quite understand. As aides to an Israeli organization in France, they go undercover traveling to Soviet Russia to connect with Jewish refuseniks.

Posing as a couple on tour celebrating their recent engagement, they enter the country sneaking in banned books and other items at great peril to themselves. Carole is the political one who has been to Israel and she especially is working with others in Israel and France in the hope of eventually securing visas for refuseniks who are secretly in touch with an Israeli organization via “tourists” who visit from France. Jérôme is with her because he is attracted to Carol and this adventure; he enjoys being with her more than upholding the cause. The code words they use to connect with the refuseniks who are being closely surveilled are, “We are your friends from France.”

Jérôme and Carole must suppress their words and actions because there are “bugs” everywhere and the KGB is on hand to question and take away anyone who appears to be suspicious. The atmosphere the filmmakers create is truly frightening, especially when the young couple nearly get caught and when those they are helping are taken in and forcefully interrogated. During their time in Odessa, they learn the dark underbelly of the subterranean oppressed culture. They experience the harsh, seedy realities of totalitarianism, the potential exploitation of their youth by the Jewish organization, and the need for escapism through sex and drugs in the stultifying environment. And they befriend the refuseniks, especially Viktor (an excellent Vladimir Fridman) who entrusts Jérôme with a journal of his incredible survival story in the Gulag.

The journal is a subversive document. If it is found by the KGB it will result in imprisonment and torture of the one who possesses it and its author. To complicate matters Jérôme has fallen hopelessly in love with Carole and is devastated when she goes off with one of the “friends” from France. His jealously puts him in an emotional flux. The directors use his emotional state to heighten the suspense and further our anticipation that he is capable of taking unnecessary risks because of it.

Is Carole seeking love elsewhere to escape her love and desire for her cousin, Jérôme? In keeping his promise to Viktor, will Jérôme safely get the journal through customs? Or will he be caught, imperiling himself and jeopardizing the consummation of his love with Carole? The filmmakers are skillful in creating thrilling intrigue. The adventure culminates in an ironic surprise ending. Weill and Kotlarski successfully reinforce the themes which show the extent that love brings the cousins and friends together through sacrifice. It is a journey where only the finest can experience and fully understand the cost of political and personal freedom.

This review first appeared on Blogcritics.