Blog Archives

‘Appropriate,’ Exceptionally Acted, Scorching, Complex, Revelatory

Appropriate’s theme

The truth is the truth, no matter how hard one betrays oneself into believing otherwise. Currently, segments of the American population have difficulty with the nation’s history of bigotry and murder and would mitigate it, not through reparations and reconciliation, but through dismissal and nihilism. As long as such masking occurs, the violence will continue in a legacy that can only be expiated and ended by confronting the deplorable aftereffects of racism head on. Such is the basic theme of Appropriate, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins harrowing, humorous, profound family drama about loss, self-betrayal, torment, fear and generational psychic damage, that is currently unraveling great performances at 2nd Stage’s Helen Hayes Theater. The drama with sardonic humor is in its Broadway premiere and has now been extended.

Before the curtain lifts onto the 7th generation Arkansas plantation home of the Lafayette family, the theater is plunged into the darkness of nighttime. Then, Bray Poor and Will Pickens let loose the prolonged, screeching sound of Cicadas, a sound repeated between acts and scenes. When Jacobs-Jenkins determines we’ve “had enough,” the lights dimly come up on a once stately mansion interior- living room, foyer, and stairs-leading up to the balcony landing and off to unseen bedrooms, where Toni (Sarah Paulson,Talley’s Folly), Bo (Corey Stoll, Macbeth), and Frans (Michael Esper, The Last Ship), slept during their childhood.

The mansion, in complete disarray, filled with hoarder’s junk-furniture, ceramics, glassware, clothing and more-still has remnants of beauty amidst its dilapidation and tawdry dressings of curtains and outdated furniture, thanks to dots’ prodigious scenic design. Symbolic of the once “glorious” South, with its penchant for ritual and gentility delivered by Black enslavement, servitude, Jim Crow peonage, bigotry and prejudice, the mansion, we come to discover, hides remnants of brutality, sadism and murder, a legacy of the Layafettes, which has not been recognized or confronted by the present generation, especially Toni.

The Backstory

In the backstory, we learn that Toni, Bo and their families are at the plantation for the auction of the estate interior, house and extensive property which includes two cemeteries, one for seven generations of Lafayette ancestors, and the other a slave cemetery isolated near the algae-ridden pond. Bo and Toni have kept in touch and were together for their father’s funeral six months prior, when they discussed raising money to pay off the loans of the estate’s indebtedness. Though they try to contact Franz, who has been AWOL for 10 years, they have been unable to tell him of their father’s death and the disposal of the estate.

It is no small irony that Franz, at the top of the play, comes in through the window with his girlfriend like a thief in the night, in the early morning hours, the day the liquidators are supposed to catalogue and price the estate’s valuables. When Paulson’s Toni makes a dramatic entrance from the 2nd floor balustrade, shining a flashlight on Franz, ranting at his presence and interrupting his reunion with her son, his nephew, Rhys (Graham Campbell), we question what is going on. From this incident of conflict, Jacobs-Jenkins unspools the mystery about the family, its members, their dead father and their ancestors. Throughout the play by agonizing and strategic degrees, the playwright reveals the Lafayette’s tragic family portrait, and explores many themes, key among them ancestral accountability for the past sins, which if not addressed or confronted, will be a curse on future generations.

As the play progresses and the siblings deal with the estate, we note that Toni, as executrix, makes unilateral decisions and controls everything to the point of “spur-of-the-moment” irrationality (though her explanations to herself are rational). This foments more chaos than is necessary in a situation fraught with turmoil, divisiveness and alienation among the siblings.

Pressures and conflicts in the Lafayette family

Pressures of the father’s illness and death, the disparate circumstances in each sibling’s family, Toni’s divorce and difficulties with her son Rhys (Graham Campbell), exacerbate the tensions of the stressful time, as the siblings attempt to create order out of chaos and obtain the most money to pay off the debts. Handling the estate and settling the inheritance would upend the most sanguine, peace-loving and close siblings. However, for the tormented Lafayettes, settling the estate is apocalyptic. The brokenness of each family member and their significant others raises the temperature of the non air-conditioned mansion to an explosive boiling point by the end of the play.

The first roiling incident begins with Franz, renamed from Frank by his California-dreaming, tendentious, sweetie, River (Elle Fanning is brilliant as the peace-keeping, pompous, shaman-loving spiritualist). The moment Paulson’s acerbic, sniping Toni sees Franz, she launches into strident questions, as he soft peddles his replies and defends himself against her accusations that he only showed up to greedily collect “his share.” When she threatens to “call the cops” on him, he ignores her and goes upstairs with River to sleep off their long trip from Oregon, where he had been hiding out for a decade.

Why she responds toward her youngest brother this way is revealed in the last act cataclysm. However, her bile-frothing attitude, while humorous and sardonic, frightens. Though she seeks hugs from her son Rhys and tells him she loves him, we question her volcanic response to Franz and fiery tirade answering Bo’s comments about shelling out money to maintain the estate through the last years of their father’s illness. Apparently, Bo paid for the aide who ministered to their father almost 24/7, and paid for all the house expenses. According to Bo, he took that “hit,” and hopes to recoup some of that loss from the proceeds of the auction and estate sale.

Questions about the kids’ discoveries

Toni dismisses him saying that it was “their father” who was ill. The implication is that he is heartless and should have opened his bank account willingly with no thought of recompense. We are curious about this “selflessness” she demands of others, while equating her time with her father and drives to Arkansas from Atlanta as more than the equivalent of the money Bo paid. Meanwhile, why wasn’t the father’s grand estate enough to pay for its upkeep? As a DC district justice (in line for becoming a Supreme Court Justice), didn’t the father have the acumen to financially manage it? Why didn’t Toni contribute monetarily, and why are there heavy loans against the property? And why did the father keep quiet about his precarious financial circumstances? Eventually, we learn the answers about this family which is so dysfunctional, it is caving in on itself by the weight of its violent legacy which they refuse to confront.

Little of what her siblings say Toni takes in giving any weight to their position or logic. She is quick to retort and uplift her own situation and attack theirs with seething anger. Whether this is a function of her age (the oldest), and her position as executrix, one concludes that it is mostly due to Jacob-Jenkins’ stylized characterizations in the service of elucidating his themes. A key theme is that karma is a bitch. Unless you break the cycle of abuse of others (slavery, murder) and acknowledge and reverse it, it comes to haunt you with its own particular brand of sickness and blight in the human heart. By the end of the play, we note how each sibling is crippled with agony, divided and isolated from each other without any possibility of reconciliation or redemption.

That this may be the result of what their ancestors had wrought upon the land they “appropriated,” and the slaves they abused, and the Black people they may have seen or had lynched, generational accountability is the last thing these present day Layafettes consider. However, adding other clues (i.e. River feeling the presence of spirits), it is a sub rosa theme of the play. Bo, Toni and even Franz hurt, lash out and move to disinherit themselves from each other, the estate valuables and the plantation which they leave to the elements, abandoning it.

Who would question their behavior? Who would want their legacy which involves lynchings (they find photographs of Blacks lynched), glass jars filled with noses, fingers, ears and penises of Black people carved out of the lynched bodies, and a Klan hood that was their father’s. Clearly, the race hatred permeated their childhood, but they didn’t realize it, having spent most of their lives in Washington, DC and some summers at the Arkansas plantation. Besides, around them, their father never mentioned the “N” word, though Bo remembers in college the judge refused to look at “in the eye,” or “shake the hand” of a Black dorm-mate.

The mystery revealed: spoiler alert.

The siblings and apparently, the father and mother, didn’t deal with their ancestry, but like so many others in the south, received the benefits of “free labor” and reaped the rewards of servitude and Black social oppression through the generations without considering the possibility of karmic reparations exacted on their being, emotionally, spiritually and psychically. Jacobs-Jenkins gives clues of the cruelty of their ancestors toward the Black population throughout, via the collector’s items and junk their father and his relatives hoarded.

That this sale of the estate represents the family’s apotheosis of failure and self-destruction, Jacobs-Jenkins uncovers by the conclusion. Bo has lost his cushy job. Toni has been fired from her teaching position when her son distributed her meds to classmates, for which he was kicked out of high school. She is finalizing her divorce and Rhys doesn’t want to stay with her but is going with his father because she is not a good mother.

We discover that Franz is only interested in collecting “his share,” after befriending Bo’s daughter Cassidy (Alyssa Emily Marvin), who broadcast family events to him via her Facebook pictures. Franz had been receiving checks from his father to pay for his upkeep after his jail sentence as a pederast (he got a teenager pregnant). During Toni’s harangues, we discover, though Franz is presently “clean,” Toni suffered with “worry” through his hospitalizations, rehabilitations and addictions to drugs and alcohol. Meanwhile, Franz blames his “bi-polar,” psychically-broken father who fell apart after his wife’s loss to cancer, as he attempted to raise Franz by indulging him. Franz also blames his siblings’ abandonment of him to his father’s questionably abusive care. Of course Toni counters Franz “defense” as lies.

The Lafayettes are an emotionally debilitated family on steroids

Jacobs-Jenkins clarifies that this is a emotionally debilitated family on steroids. Maybe the only member with any rationality is Bo, but only because of his wife. When discussing their father’s racism and prejudices, which Toni denies, Rachel mentions she overheard their father slur her when he referred to her on the phone with a crony, as Bo’s “Jew wife.” Toni dismisses her and the race hatred artifacts. She is “put-out” by Rachel’s alarm that the children have seen the photo album of Black lynchings and incensed that Rachel implies her father is anti-semitic and racist, she ends up provoking Rachel to provoke Toni to slur her. Toni does with ironic abandon, then claims she was joking.

Interestingly, Bo, who lives in the North has put a great distance between himself and his heritage, which is another form of dismissiveness. However, he has taken his racist attitudes with him. He attempts to recoup money from the estate by arranging to sell the photographs of the lynchings of Blacks, which apparently are valuable on a covert white nationalist market of sadistic memorabilia of the “good ole” Southern “glory days”

Bo is so numbed to his legacy, he doesn’t see the egregious amorality of making money off others’ victimization and death. This is a corrupt continuation of the “benefits” the South receives from its Jim Crow policies of racism and murder, heightened by the fact that there is a market for these “valuable collector’s items.” Though each revelation of the father’s racist hoardings is achieved through the kids’ innocent, sardonic, humorous discovery, as the adults try to cover up the shocking “in-your-face” racism, the audience’s real shock is at the macabre, psychotic nature of keeping such items. We ask, why would the father, a judge, “get off” on photos of Black lynchings and jars of Black body parts from the lynchings?

Who does the photo album belong to or the glass jars of body parts?

Toni, Bo and Franz don’t find this loathsome about their father, and try to pretend it belongs to someone else.

Jacobs-Jenkins clarifies the craven, broken psyche of Bo, Toni and Franz, who don’t see anything wrong with selling these items to recoup the estate’s losses. On the other hand, Rachel is outraged her children have been the ones to discover the photo album and jars of body parts. And at some point, she intends to discuss what they mean with her kids to work through the psychological shock of seeing such horrors. Indeed, she is the only one who seems to understand the brutality and violence such artifacts signify. It is her morality that stirs the morality of the others to try to protect the kids from further exposure. But Cassidy is interested because it is verboten, so she continues to look, seduced to the grotesque, cruel voyeurism that this American past was normal for the South..

The playwright speaks volumes through what is absent in the siblings’ conversation. They don’t deal with why the father hoarded such items and didn’t find a better place for them in the Smithsonian African-American History Museum, Arkansas African-American History Museum, or other educational institutions or museums. Why has he kept the photos in a shelf in the foyer, and the Klan hood and the body parts in his bedroom? They weren’t secreted away in a hiding place in the attic or elsewhere, but were out in the open. Obviously, there are two sides to the retired judge’s character. One part of him justifies lawless lynching via white domestic terrorist racism, while the other lives peaceably as a justice. Perhaps Franz has a better handle on his father’s “bi-polar” nature than Toni, who disbelieves all of the “incongruities” Bo, Rachel and Franz have pointed out about him.

The final coup de grâce

Jacob-Jenkins cannot resist the final coup de grâce on this tragic, racist, family legacy that is blowing up in their faces with regard to recouping money. Bo states the land cannot even be sold without dealing with the two cemeteries, so the property isn’t worth much. Secondly, Franz,, to “cleanse himself and get in good with his family,” throws himself and the photos into the pond by the slave cemetery before he knows they might be valuable. The photos are destroyed; the money up in smoke. This family can’t win for losing. Have the spirits of the dead effectively prevented any benefit to a family with its violent legacy of slavery and lynchings, as karma takes its recompense and the estate goes into receivership?

River, who has from the start been wary of the spirits on the place and has sensed “a presence” in the mansion, is used by Jacobs-Jenkins to validate this possibility that the spirits of lynched, enslaved African-Americans exact their karmic retribution. Additionally, the playwright and director’s vision reveal that such spirits may seek vengeance until the family expiates the bloodshed and torment their forebears have wreaked on the Black population on their lands. Thus far the current generation hasn’t and the siblings are a wreck.

The tragedy of blindness is on everyone in this family, who ignores the significance of those murdered, lynched, abused and oppressed. The lives of those in the slave cemetery and those in the photo album are like the lives of Blacks across the South, who were and are still being appropriated for money on the covert market of “lynching” items that white, terrorist racists find “quaint,” “cool” and “prize-worthy” for trading. It is an unacceptable criminal abomination that must not be normalized. It still is at what cost?

The siblings abandon the mansion and its contents which nature takes over and destroys through the decades as it collapses and a final haunting symbol emerges in the mansion center stage. It is a huge tree open to interpretation. It is representative of the lynchings in the photograph album which must be accounted for.

An amazing conclusion

The conclusion after the blighted family members have left, never to see each other again, is an amazing scenic feat. A tree rises from the mansion floor effected by the amazing scenic designers, dots. Neugebauer’s vision with dots’ execution of the house symbolically shattering as the tree rises up from the foundation of racial hatred, brings together Jacobs-Jenkins’ themes. They warn that despite assuming all is well, recompense will continue to be exacted for historic racial bloodshed and murder. As this family has a legacy of it and refuses to confront it, a bill for the bloodshed will be delivered on them and future generations, via psychosis, financial ruin, addiction etc. Karma is a bitch.

The play is exceptional in its themes and important in its significance about recognizing and not normalizing racial murder and lawlessness as the family tends to do when their father’s hidden life uplifts it. The characterizations serve the themes; the themes don’t arise from the characters. At times the dialogue is contrived to be humorous, especially as the playwright has stylized these individuals as types. Toni’s character is drawn as sardonic, insulting, shrewish and one-note.

The reason why the production gets away with the contrivances is because the director’s staging is perfection, the technical creative team is superbly coherent in conveying her vision. Most importantly, the actors are incredible, individually and as an ensemble. They flesh out and inhabit these unlikable individuals and make them watchable and horridly humorous. Paulson brings her own star quality and beauty to the role so we dismiss Toni’s obnoxiousness, until as with all of them, their faults gradually clarify and deaden them. Then, we reach the point of no return.

By the end we could care less that Toni declares herself dead to the others as they are dead to her. We watch as Bo weeps and questions why he cries. We assume that Franz will continue in his lost state with River directing him until she gets fed up. And Toni sums up what each of the siblings is thinking. She affirms this is who she is with them, implying they “make her” this way and she doesn’t like herself as a result. It is the same for Bo and Franz, who aren’t particularly happy with themselves. Neither do we empathize with any of them because they don’t acknowledge their legacy, they dismiss it or run from it. As their ancestors “threw away” Black generations, so these individuals in self-torment, “throw away” themselves…a tragedy.

This family is the problem and not the solution which is hard won. And as the themes imply, there must be recognition of the horrors of murder and reparations must be attempted. Karma is taking its toll. The sooner the crimes and injustice are recognized, the better for all who have a legacy of violence as this family does. Regardless of how disconnected they think they are from it, they are suffering and will suffer until the injustice is made right.

Kudos to the creative team not identified above. These include Dede Ayite (costume design) and Jane Cox (lighting design). This is not one to miss in its profound themes about the South, about normalizing crimes, and dismissing their historical significance and impact on us today.

Appropriate, two hours thirty minutes with one intermission at the Helen Hayes Theater, 240 W 44th St. between 7th and 8th. https://cart.2st.com/events/?view=calendar&startDate=2024-1

‘A Bright Room Called Day’ at The Public, Tony Kushner’s Haunting Spectres Thread Through Hitler’s Berlin, Reagan’s 1980s and Trumpism

Nikki M. James, Michael Esper in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Tony Kushner’s A Bright Room Called Day directed by Oskar Eustis, currently at The Public until 15 December (unless it receives another extension which it should), reflects upon humanity confronting evil that on a number of levels appears unstoppable and irrevocable. Throughout the main action and play within a play, Kushner makes clear that those who recognize evil’s force and preeminence, often are too afraid to lay down their lives to fight, though fighting is the action needed to stop wickedness in political, social and economic institutions not constrained by the rule of law.

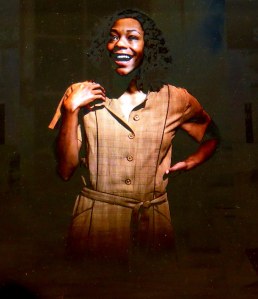

Nikki M. James in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The play uses at is jumping off point political and social issues undermining the Weimar Republic in Berlin. The setting encompasses events one year prior to the “Eve of Destruction,” when Hindenburg acceded to Hitler’s government take-over after which Hitler evicted parliamentary, constitutional democracy from the minds, hearts and souls of the German people. Kushner examines the parallels of that time with our culture during Reaganism and Trumpism.

The questions he raises are pointed. Some might argue that from the 1980s to now, the decline in our democratic processes and the public’s response appear similar to the public’s response to precursor events in Germany 1933. A Bright Room Called Day relates Berlin, Germany 1933 to 1985 Reaganism, devolving to the time of Trump. These three settings represent a turning point when the crisis of the period might have shifted in another direction if good citizens acted differently, affirming the adage, “evil flourishes when good men and women do nothing.” In this play Kushner examines the “What if?” Couldn’t citizens have halted the terrifying dissolution of democracy? Couldn’t they have liquidated Hitler’s fascist dictatorship before he even attempted to manifest his warped vision of the Third Reich’s reign for 1000 years?

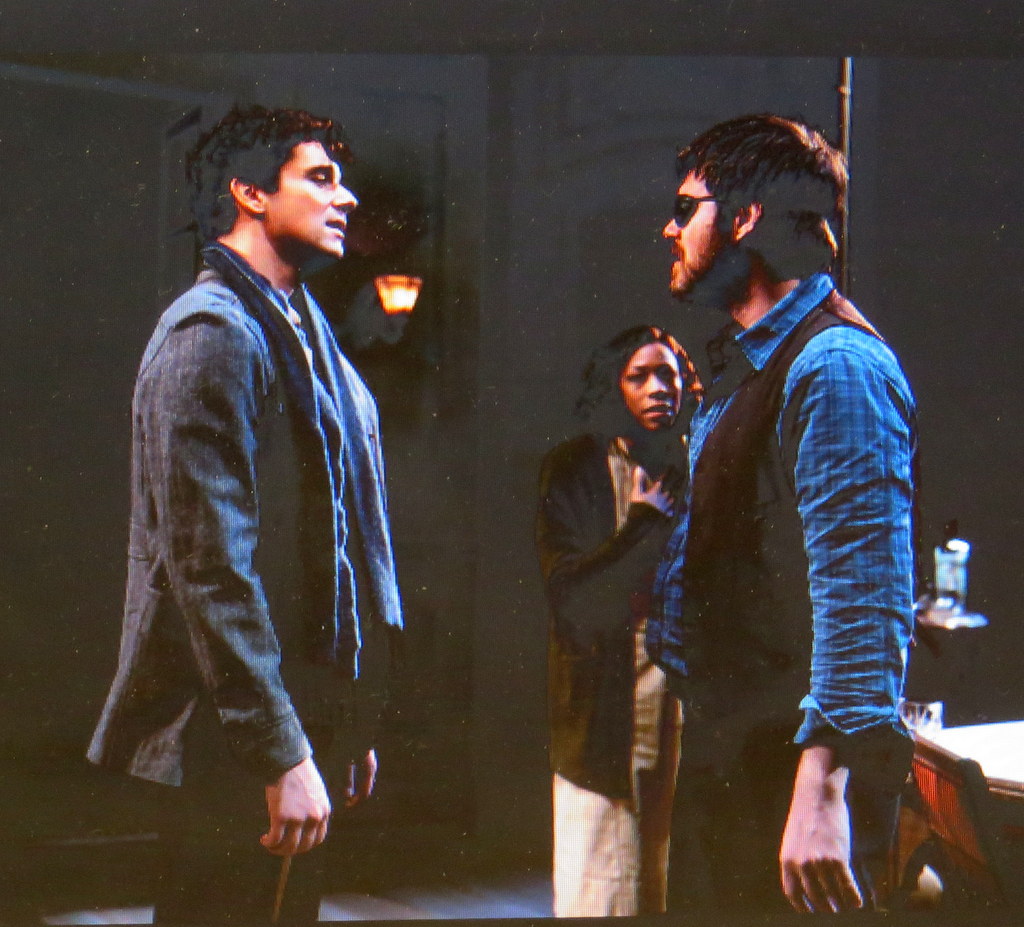

Michael Urie, Nikki M. James in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The community of individuals we meet at the outset of the play who pop in and out of Agnes Eggling’s (Nikki M. James) lovely apartment are members of the political, liberal left, a combination of artists and activists who are/were at one point communists, socialists, progressives and union activists, one of whom is a homosexual (played by the exquisite, always present Michael Urie). All of these will be consigned to Hitler’s enemies’ list if they remain in Berlin. If captured, they will be deported as state enemies and undesirables and murdered when Hitler constructs and augments his network of slave labor and extermination camps to implement his “Final Solution.”

Kushner’s work which was excoriated when it first premiered in the 1980s has been given an uplift with an additional character, and dialogue tweaking to reference the current siege of Trumpism on our democracy. Kushner posits that our times manifest “inklings” similar to those employed by fascists and Reagan’s corrupt conservatives who sent the nation on a downhill slide which Trump appears to be pitching over the edge into oblivion, unless we do something. By drawing comparisons, we are forced to reflect upon the upheaval in our democratic institutions as the political, economic and social divisiveness spurred by Trumpism augments.

Kushner interjects his own commentary as a playwright and interrupts the action during which he actively engages his audience as a silent character whose consciousness he manipulates. Through identification with the people and events in Germany, we, like they, become like the frog that is placed in a pot of cold water. As the heat is turned up to the boiling point, if the frog is alert, he can escape before boiling to death. But he must realize immediately what is happening, so he will not be too lamed to escape. By degrees the audience realizes that they are in a crucible like Kushner’s characters, under which a fiery truth blazes. To that truth Kushner posits, one must recognize it, or its heat and pressure will pitch one into a death-state of paralysis like Agnes’.

Crystal Lucas-Perry in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The play’s new character is Xillah. Xillah represents Kushner’s perspectives as a citizen playwright who comments on his play and the policies of Reaganism and Trumpism. Playwright Xillah engages with Zillah his indefinable character whom he’s written into the 1980s. Zillah complains to Xillah about her function in the play. She importunes him for a viable role and purpose. She wishes to step beyond ranting about the emotional paralysis of character Agnes. Watching Agnes frustrates Zillah, for Agnes does little but quiver in fear at the ever-worsening events in Berlin. It is her fears which manifest nightmare presences (Die Älte-the Old One, in a wonderful portrayal by Estelle Parsons) who haunt her and drive her into soul paralysis which will lead to her death under Hitler’s regime.

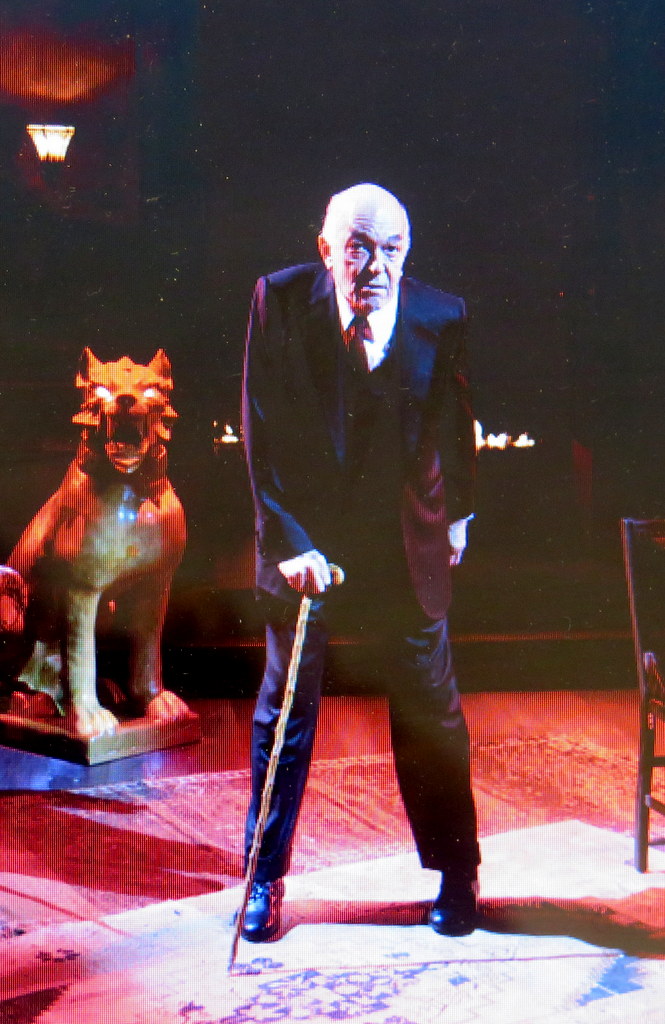

Estelle Parsons in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Xillah, a character in the play framing the Berlin events is portrayed with humorous vitality by Jonathan Hadary. His character criticizes the activities by the cults of Reagan and Trump. He sardonically characterizes Reagan’s presidency and Trump’s “monolithic” personage with abandon in a stream of hysterical epithets that are right-on. Both Xillah and Zillah (Crystal Lucas-Perry is Hadary’s counterpart in a feeling portrayal) comment on the dynamic of the Berlin characters which Xillah (as Kushner) has created. They watch as Agnes, Paulinka (the superb Grace Gummer) Baz ( Michael Urie) Husz (Michael Esper) Gotchling (Linda Emond) and comrades Rosa Malek (Nadine Malouf) and Emil Traum (Max Woertendyke) grow morose and desperate, experiencing the dissolution of the German Republic into fascism. They palpably encounter the manifested evil of the time in the form of Gottfried Swetts (Mark Margolis humorously intrigues in his portrayal). He is the Devil, whose darkness overtakes Germany as Hitler ushers himself into the government and eradicates any goodness that went before.

Kushner’s characters argue about communism, socialism, democratic socialism and the state of affairs. Their discussions fuel their waning activism and encourage impassivity with a few exceptions, for example, Gotchling (Linda Emond), who is continually putting up posters which are torn down continually. We empathize with the Berliners as they react to the brutalities and street fighting, Hindenberg’s ending the government and the Reichstag fire which Hitler blamed on the communists to ban the party, arrest the leaders (his enemies), and consolidate his power base.

The characters react emotionally with disgust and outrage but their impulses to act are largely stymied by fear. They will not move beyond marches and protests that the Brown Shirts help to render bloody and ineffective. And when back room deals are made to put Hitler in power, they become powerless. Like many they appear to believe the propaganda rallies that show support for Hitler, though initially these are largely staged until the rallies gain in momentum and many join Hitler’s party.

The historical events are chronicled with vitality. The characters reveal poignant moments expressing the mood and tenor of the like-minded populace. Baz relates a story of a man’s suicide and his imagined wish to take one of the oranges, he, Baz, has purchased and give it to the dead man as a comfort. Of course, Baz never gives him the orange, but he imagines having done it, ironically comforting himself as the man is beyond being comforted. For Baz it is a horror seeing the dead man’s body pooling blood around it. Baz identifies the cause of the man’s suicide as the despair and immobility to stop the terrible events in Berlin. The suicide rocks Baz to the core. We align the man’s suicide with Baz’s suicide attempt which he stops himself from committing when instead, he has a sexual encounter. Baz’s choice is ironic and the impact of the suicide he witnessed in the streets is nullified by sexual distraction. As Baz, Urie delivers another incredible story later on which sets one reeling. Again, when Baz could take a stand, he chooses not to. Throughout, Urie’s performance is spot on amazing.

(L to R): Jonathan Hadary, Nikki M, James, Crystl Lucas-Perry in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

In the “intervening” frame play, Zillah attempts to persuade Xillah to write her with character powers that transcend time and space and go back to the past to warn Agnes of the danger of embracing fear and doing nothing. Zillah is upset that Agnes is so overcome, she is zombie-like. One of the humorous parallels is that Xillah, too, is at an impasse (like Agnes) only it is about the direction of this play and how to make it more vital so that it will have a resounding impact on the audience and get them to act. But he is filled with doubts about the function of plays. Also, he fears tampering with what he has already written. Indeed, he could make his play into a worse failure. His quandary is humorous.

Kushner, the frame (the present and 1980s) around which houses his Berlin character dynamic has Xillah remind Zillah of a number of important details, in addition to the chronological events of Hitler’s takeover. As Xillah parallels the then with the now, he affirms that friends living against the backdrop of Trumpism suggested he revisit The Bright Room Called Day because it is prescient and current. Xillah wrangles how best to show the similarities and complains that the characterization of Zillah doesn’t work. However, the character very much integrates the parallels. She criticizes inaction when a nation’s political/social structure disintegrates because the populace becomes overwhelmed and doesn’t act, becoming paralyzed as Agnes is paralyzed. The question remains: how does one move out of paralysis and take effective action which will change things for the better?

(L to R): Crystal Lucas-Perry, Jonathan Hadary in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The threads of alignment that Kushner makes with Germany that mirror our present are thematically chilling. Xillah reminds Zillah that the Weimar Republic had a constitution like the U.S. but their constitution didn’t save them against Hitler who abolished it. With the constitution gone, Hitler and his underlings and judiciary created laws to further Hitler’s occult mythic vision (the Master Race). And with his own race laws, he legalized the genocide of millions. Of course, Kushner highlights the turning point when death and destruction could have been prevented during the events of 1932-33. But those who saw, like Agnes and her friends, chose to do nothing. Eventually, like the frog slow boiled in the pot, the only thing they can do is escape. If they, as Agnes did, stay, they will be killed or swallowed up like Paulinka to join Hitler’s Third Reich “support group” of murderous maniacal, psychotic, evil accomplices. A different type of death, certainly more horrific and self-recriminating.

Mark Margolis in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Xillah muses about changing the play and warns Zillah that Agnes can’t hear her: she is dead as the past is dead. Zillah continues to beg Xillah. The dialogue that Kushner has written between them is humorous and reminiscent of the “Theater of the Absurd” genre and Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, where the playwrights tweak dramatic conventions. This is done to expand audience consciousness. Such creative license demands being available to “thinking outside of the box.” It also leads to the audience having to follow a play’s absurdities which can be as confounding as the illogical, dire thrusts of fascism, Reaganism, Trumpism.

Linda Emond in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The absurdist feeling becomes that one has been caught up watching oneself as a part of the larger picture which one deludes themselves into believing they can control. In fact the “author” of our lives is not one we’ve necessarily chosen or know. At least Zillah knows her progenitor and argues with him and finally convinces Xillah to lift space/time constraints so that Agnes hears and speaks to her.

This section gives rise to a number of themes in this work that is dense with brilliance. Before Zillah connects with Agnes, we note that Agnes’s spirit atrophies and dies because her fear incapacitates her. Even if Zillah could break through the time barrier and move from the 1980s to 1933, Agnes’s routine of embracing fear and inaction has warped and destroyed any life in her. Life is movement, action, vitality. Doing something, anything (even escaping) would be better than just withering away. The irony of the play is the melding of the frame play into the Berlin story by Kushner/Xillah. He finally allows Zillah to warn Agnes to leave because she is doomed. Though it is not mentioned, we understand that those who did leave Germany early on did manage to save themselves while millions were swept up in genocide and Hitler’s war machine.

(L to R): Michael Urie, Michael Esper in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Agnes’ reply to Zillah is not what we expect. It is mind-numbing, a warning to Zillah and us about our own time. It has the effect of a final incredible bomb blast that whimpers and fades. The full-on irony is as Agnes exhorts her/us, we hear, but it doesn’t register, it doesn’t matter. Thematically, Kushner suggests that we are plagued by the same inabilities, insufficiencies and cowardice that Husz ranted about in an earlier magnificent scene. Time inevitably doesn’t matter as we are like Agnes. Paralyzed, immobilized by discussion doing little to save ourselves. We must act! But how? To do what? And so it goes.

Kushner’s play should be revisted and it is a credit to The Public and Oskar Eustis for bringing it back in this unsettling, frustrating iteration. The parallels with each time period, whether we deign to acknowledge them or not, are striking. The threads which indict us about our alienation and powerlessness are spectres which should prick us to the marrow of our bones.

Indeed, in our time as we watch the separation of powers (executive, legislative, judiciary) illegally devoured by the Trumpist Party with the DOJ stomping down its own institution (i.e. the Inspector General’s Report exonerating FBI officials whom the WH has slandered and insulted) and mischaracterizing the Mueller Report, such “above the law conduct” to loyally support the WH is frightening and dangerous. Additionally, in our time, we note how the Trumpist Party encourages law breaking of fired officials (lawyers and others) to defy congressional subpoenas tantamount to obstruction of justice. And currently, high ranking members of the Trumpist Party in the House of Representatives refuse to listen to non partisan congressional testimony which implicates the White House in potential bribery of a foreign leader, withholding appropriate congressional military aid in exchange for a political smear of the White House’s opponent. In other words, they refuse to uphold their constitutional oath of office and do their job, instead uplifting the “dear” leader’s loyalty pledge to support him in his criminality.

These are high crimes and misdemeanors to add to a long list of acts which we need whistleblowers to come out and speak about: Trumpist bribery of foreign leaders, quid pro quos, his acting above the law, his incurring human rights violations, overthrowing military law, and Trump’s blatant importuning of foreign nations and adversaries to help him overthrow our election processes with smear campaigns against his opponents, the indefensible practice he used to win the 2016 election.

Max Woertendyke, Nadine Malouf in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Such lawless behavior in an executive that easily vitiates the separation of powers, and bullies, insults and retaliates against anyone who would attempt to point out his law violations recalls behaviors of fledgling dictatorships. Such dictatorships grow. They make laws into what are solely “good” for the dictator/autocrat as they obviate what is good for the rest of the body politic. And if one counters with opposition? That autocrat will bully, intimidate, censure, retaliate and eventually when no one stops them, kill or destroy any opponents using what it can get away with, first character assassination, then jail, then well placed convenient suicides (check the google article about Deustche Bank’s suicides) then murder.

One may argue that Kushner’s alignment of the present U.S. “leadership” with Germany’s situation in 1932-33 is extreme and overblown. Really? And indeed, if the play “doesn’t work,” are the themes and presentments just too horrible to contemplate? Are we, like Agnes, too overcome, too PTSDed by the WH’s horrific acts to consider that we have already lost our constitution and democracy to an overweening, unlawful executive branch whose party refuses to adhere to constitutional checks and balances?

Kushner’s A Bright Room Called Day raises so many parallels, similar threads and questions, that it should be seen. It should be seen not only for the superb performances, but for the humor, for the pith, the juicy pulp of the orange that is being offered as a comfort. And it should be seen as the bright bit of light in the sky before the darkness closes in and we can no longer see clearly fact from fiction. While there is that bit of light, we must discern conflicting alternative narratives from the propaganda that would occlude our minds, souls and hearts and propel us away from human decency and love for each other as citizens of a nation worthy of its ideals.

Kudos to David Rockwell (scenic design) Susan Hilferty and Sarita Fellows (co-costume design) John Torres (lighting design) BRay Poor (sound design) Lucy Mackinnon (projection design) Tom Watson (hair, wig, makeup design) Thomas Shall (fight director). A Bright Room Called Day runs with one intermission at The Public Theater until 15 of December. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.