Blog Archives

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

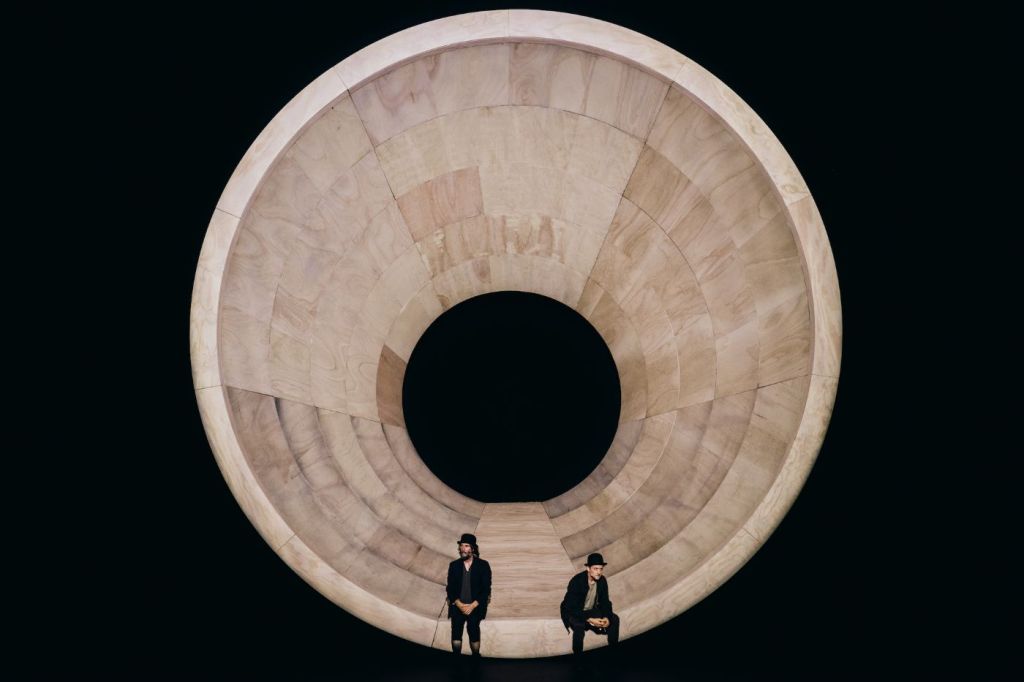

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.

‘A Doll’s House,’ Jessica Chastain’s Nora is Brilliantly Unbound

As a masterpiece of modern theater Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House presciently foreshadowed the diminution of a women’s role as homemaker. Ibsen shattered the notion of a woman being a husband’s pet, an obedient robot/doll with no autonomy or identity of her own, who cheerfully accepts the delimitation of traditional folkways. A maverick play at the time, A Doll’s House was considered controversial. Ibsen was forced to rewrite the ending for German audiences so it was acceptable.

What would those audiences have said about Amy Herzog and Jamie Lloyd’s stark, minimalist, conceptually powerful, metaphoric version currently at the Hudson Theatre? It is a version which relies on no distracting accoutrements of theatrical spectacle, i.e. period costumes and plush drapery. Nothing physically tangible assists with the unlacing of “the bodice” of Nora’s interior. With “little more” than cerebral irony, and emotional grist, Nora displays her soul in a genius enactment by the inimitable Jessica Chastain, in the production of A Doll’s House, which runs a spare one hour and forty-five minutes with no intermission.

The plot development, characters and themes are Ibsen’s. Nora, a pampered, babied housewife, to save her husband’s life, unwittingly commits fraud by borrowing money from loan shark Krogstad (Okieriete Onaodowan who in the first scene needed to project his voice so as not to appear a weak character which Krogstad is not). Complications arise when Torvald (an exceptional Arian Moayed), receives a bank promotion. With the additional money, Nora plans to quickly pay back Krogstad. But the loan shark threatens to expose Nora’s secret, unless she can save his job at the bank, where her husband has just become his boss.

Tensions increase when Torvald fires Krogstad and hires Nora’s friend Kristine (Jesmille Darbouze). Nora must confront the situation with Torvald before Krogstad exposes her and destroys Torvald’s reputation and their marriage.

Lloyd and Herzog are a fine meld. Herzog strips extraneous words and phrases, though not the substance of the pared-down dialogue. Her version is striking with a natural, informal, un-stilted speech for concentrated listening. There’s even a “fuck you” which Nora proclaims cheerfully to be bold, though not in Torvald’s hearing. The meat is Ibsen; the forks and knives to devour it are sleek and without ornamentation to distract. The themes and characterizations are bone chillingly articulate, which Herzog and Lloyd excavate with every word and phrase in this acute, breathtaking, ethereal, new version of A Doll’s House.

Lloyd eliminates the comforting, elaborate staging where actors might have moved to and fro amongst luxurious furniture and eye-catching, gloriously-hued dramatic sets that show Torvald’s preferred, lifestyle, which Nora scrimps from her own “allowance” to maintain. Instead, the ensemble’s movements are restrained. They step quietly around Soutra Gilmour’s set. Gilmour has distilled Lloyd’s vision to the back stage wall, top-half painted black, with attendant muted white painted on the bottom half of the wall. The flooring is grey. Predominant are the revolving platform and institutional-looking bland chairs which actors bring in and place on the sometime circling platform, or on its outer edges which don’t revolve.

Chastain appears twenty minutes before the production begins, seated in a chair revolving on the platform (I should have counted the repetitions, but I didn’t.). Sitting, she fascinates. Initially, to me, she was invisible; I was distracted, while she quietly walked on bringing her chair. She was a part of the onstage background, muted, unremarkable. That is perhaps one of the many concepts Lloyd and Herzog suggest with this enlightened version that is memorable because it is metaphysical and conceptual, giving rise to themes about soul interiors and women’s invisibility in the patriarchal culture.

One theme this set design suggests is that we travel in our own orbits, going in circles in our own perspectives, unseen and never truly known as psychically present, spiritual beings. And as Ibsen suggests, it takes an inner cataclysm such as Nora experiences to break from traditional mores and behavioral repetitions into a different consciousness and new way of being. This breakthrough, Nora attempts at the conclusion.

Amy Herzog’s modernized language version of A Doll’s House is one for the ages in focusing Ibsen’s power of developing characterizations. It presents an opportunity for Lloyd’s preferred, stylized, avant-garde staging, similar to what he used in Betrayal (2019) and Cyrano (2022). It requires the audience to listen acutely to every word of the dialogue and scrutinize the actors splendid, nuanced emotions which flicker across their faces. This is especially so of Chastain’s Nora, who is chained and bound symbolically throughout, minimally using gestures or any physicality, as she sits in a chair facing the audience. Predominately. she employs her voice and face to convey the interior-organ manifestation of Nora’s tortured, miserable psyche. For example when the wedding ring is returned, Nora and Torvald do not move; there is no ring. They look at one another, however, the unspoken meaning resonates loudly.

Even the tarantella Nora dances at the costume party, Chastain wrenches from herself sitting in the chair in a frantic nearly psychotic frenzy of shaking and kicking. The earthquake physicality that splits Chastain’s Nora apart is the only broad, physical movement, other than walking out of her stifling, meaningless existence, that Chastain and Lloyd effect with novel irony at the conclusion. The chair-dance is an explosive, rage-filled fit of exasperation, principally done for the purpose of distracting Torvald. Desperate to prevent his discovery of corrupt loan shark Krogstad’s blackmail plot, Nora’s diversion succeeds for a time. However, her fear and inner bleeding wounds only augment, until her behavior is exposed and Torvald unleashes his fury, vowing she must not infect the children with her poisonous corruption. Interestingly, the children ethereally “appear” as voices in voice- over recordings. Nora speaks to them, looking out in the direction of the audience. Hypocritically, Torvald demands she stay away from the children, though she must remain with the family to keep up appearances as his jeweled asset and prize doll.

With Lloyd’s symbolic staging, Chastain’s Nora proves that body, soul and mind are inseparably engulfed in the trauma of a paternalistic culture, represented by males who “love her the most” (her father and husband), and psychically straight-jacket and gaslight her to adopt their thoughts, behaviors and attitudes as right and true. To do this she nullifies her existence as a “human being.” In this production, Herzog, Lloyd, Chastain and the ensemble display this truth. It is undeniably representative of women in 1879, the projected number on the back wall of the stage that appears in the beginning of the production.

And when the number disappears, we understand that Soutra Gilmour’s black, white, grey set design, and Gilmour and Enver Chakartash’s costume design (modern dress black), function to speed us through 140 + representative years to display the dominant patriarchal attitudes today. These folkways still straight-jacket, demean and traumatize. If one thinks this is fatuous “woke” hyperbole that is finished, one has only to read the one in four statistics of women who are bound in violent relationships with male partners who beat or abuse them, yet cannot leave for fear of being alone or without the means to support themselves or their children. The LGBTQ community is not excepted from this. Humanity has a penchant for violence. If it is not externalized, the violence is psychic and emotional, where not a hand is raised toward a partner, yet the words and silences traumatize. It is the latter psychic trauma that Ibsen/Lloyd explore.

Whether in Ibsen’s historically, visually laden production of A Doll’s House, or in Lloyd’s naked, bleak and blasted version, it is a despotic spirit that demands obeisance, excluding other ways of being to exalt itself by oppressing and choking the life force from “the other,” whether gender-conforming or LGBTQ. That Chastain has the chops to convince us that we are witnessing every stressed fiber of her nerve endings annihilated, as she inhabits one of the most well-crafted characters in drama, is astounding and not to be underestimated, as some have done, implying her Nora “cries too much.”

Suffice to say, those are not female critics, of which there are far too few. However, her performance is emotionally handicapped accessible for those without a hearing ear, who may need to see Jamie Lloyd’s phenomenally sensitive direction a few times to “get it.” And happily many men do get it. They stood, cheered and whooped during the curtain calls when I looked around to see who was standing at Wednesday’s March 14th matinee. More importantly, women also cheered and whooped.

Clearly, husbands/partners, who might be like Torvald, need to see this production, if they suspect they are like him. Chastain’s Nora is an educational experience in how a particular woman suffers to the breaking point in order to be the prototype ideal wife and mother for a man’s “love” and acceptance. When Nora finally realizes she has the tools to free herself from the false and illusory prison of her own making, she throws off a life and role she believed made her happy to search for definitions of her own happiness.

Moayed’s Torvald, who portrays the solipsistic, presumptuous, self-aggrandizing, martinet with likable charm (how he does this is incredible), exposes her to herself. He smashes her fantasies that he is a white knight, who will do the “beautiful thing,” by sacrificing himself for her, as she has done for him.

Unfortunately, the only one who would sacrifice himself for her is on his way out of life. Chastain’s scenes with Michael Patrick Thornton’s Dr. Rank, who is the couple’s terminally ill close friend, are touching, warm and human, unlike her scenes with Torvald. They should be together, but she won’t push their light flirtations beyond, loyal to her fantasy of Torvald, until she isn’t.

Interactions between Nora and Torvald are increasingly transparent as they devolve into Torvald’s eventual explosion and hatred directed at Nora after discovering the truth. The scenes between Krogstad and Kristine pointedly contrast and move in the opposite direction. Kristine’s persuasive love of Onaodowan’s Krogstad makes him swallow his “pride” and give up his extortion plan. Truth is at the core of their love. Onaodowan and Darbouze are particularly strong and authentic in their scene together which reveals Kristine and Krogstad’s love has remained over the years. On the other hand Torvald and Nora’s toxic relationship functions in falsehoods. Lies are at its core, and what is presumed to be love is convenience and objectification. Torvald demands Nora be his dream doll and she obeys, though it demoralizes her soul.

Kristine’s troubled life has brought her to an understanding of herself in an honesty which Krogstad appreciates, for he wants to give up his corrupt way of life. That Lloyd has selected two Black actors to portray these characters reveals an underlying authenticity and exaltation for their love. Krogstad, who is in the shadows when we first meet him, as he sits behind Nora and blackmails her (unfortunately I had to read the script to understand these lines), appears the villain. He is made more villainous by the society’s ill treatment of him, but his love for Kristine redeems him. Torvald’s inability to love Nora damns them both.

Ironically, when her friend’s love is rekindled, Nora’s love ends, as she realizes Torvald’s true nature and relationship to her. Though he apologizes for “going off” in a diatribe superbly delivered by Moayed, Torvald’s narcissism which can’t abide anything hurting the Torvald “brand,” is egregious. His presumption is a delusion, for she saved his life; he wouldn’t exist but for her.

Herzog’s spare dialogue reveals how loathsome Torvald is in the last scene, when Nora tells him she believed him to be her white knight who would take the blame for her mistake. She insists she would have killed herself to stop his sacrifice for her. It is laughable when he says he would do anything for her, but he “won’t do that.” With conviction speaking for the entire tribe, Moayed states, “No man sacrifices his dignity for the person he loves.” Nora counters, “Hundreds of thousands of women have done that.” When Torvald begs her to stay for the children, he is the weak, despicable coward. His concern is pretentious show to make her feel guilty for leaving. Nora can’t be pressured. She knows Torvald will dump the inconsequential children’s care on their Nanny Anne-Marie (Tasha Lawrence).

Nora allows Torvald’s toxic masculinity to forge the chains which she uses to bind herself in the confines of a paternalistic culture that promotes attitudes about “the little wife.” Meanwhile, his little “bird” lacks a being and ethos apart from him. The only freedom, identity and empowerment Chastain’s Nora will ever receive is one she fashions for herself. This, she ironically and joyously enforces at the play’s conclusion.

How are such incredible performances by Chastain, Moayed and the others so beautifully shepherded? Lloyd economizes to the essence of thought in the lines reworked by Herzog. The evocative minimalism heightens the play’s timelessness and draws into crystal clarity the subtle, “loving” oppressive fantasies men and women (or whatever gender relationships), rely on to sustain power dynamics in their coupling. Without underlying truth and honesty to bolster the relationship and weather horrific storms, the illusions become insupportable and the personalities and relationships shatter.

Kudos to all in the creative team I may not have noted previously, including Jon Clark (lighting design), Ben & Max Ringham (sound design), the ominous, haunting music by Ryuichi Sakamoto & Alva Noto, and dance choreography by Jennifer Rias. For tickets to this maverick production, go to their website https://adollshousebroadway.com/