Blog Archives

‘Here There Are Blueberries,’ No Evil. Just Ordinary, Enjoyable Routines.

Here There Are Blueberries, now in its third extension at New York Theatre Workshop, is a many-layered, superb production running until June 30. Stylized and theatricalized as a quasi-documentary that travels back and forth from present to past to present by enlivening characters in various settings, the play unravels the mysteries centered around an album of 116 photographs taken at Auschwitz. Though the album has no photographs of the victims to be memorialized, it eventually is donated to archivists at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, by a retired U.S. Lieutenant Colonel.

Based on real events, interviews, extensive research and photographs rarely seen of the infamous concentration camp from another perspective, the play follows archivists who shepherded the photographic artifacts toward a greater understanding of the political attitudes and the daily routines of the people who ran the camp. Written by Moises Kaufman and Amanda Gronich, and directed by Moises Kaufman, Here There Are Blueberries is a salient, profound work that has great currency for our time.

With expert projection design by David Bengali, Derek McLane’s scenic design, which suggests the archivists’ workplace, and Kaufman’s minimalism, characters/historical individuals step forward to bear witness, like a Greek chorus, to speak from the ethereal realms of history. The play which has some Foley sound effects for purposes of interest, dramatizes scenes which hover around a concept. All of the fine artistic techniques by Dede Ayite (costume design), David Lander (lighting design), Bobby McElver (sound design), further the plays probing themes which examine questions the researchers ask about those who murdered and why they murdered. As the drama poses questions to its audience and itself, some, the play answers. Others, the audience must answer for themselves.

At the outset, a narrator explains the importance of the Leica camera for the people of Germany in the 1930s, when the society was at a crossroads after economic depression and the reformation of Hitler’s new government. Perched on a stand center stage is the camera in the spotlight, while projections of black and white photos scroll in the background, exemplifying the subjects taken by people using it. Some are of German people enjoying family events, as we note the narrator’s comment that in Germany, amateur photographers took up the activity as a national pastime and became “history’s most willing recorders.”

As the photos scroll showing stills of children and young adults giving the Hitler salute, the narrator suggests that “each frozen moment tells the world this is our shared history.” Her tone is ironic and the Hitler salute, as terrible as it is, physicalized by the bodies of children, indicates an alignment with Hitler’s politics, attitudes and way of life. Additional photos of children and adults enjoying outings, show Nazi flags; the narrator continues, the “apparent ordinariness of these images does not detract from their political relevance.” Indeed, she states, “On the contrary: asserting ordinariness in the face of the extraordinary is in itself, an immensely political act.”

In photographs and videos of Hitler’s marches by soldiers of the Third Reich (shown in the Nazi propagandist films of Leni Riefenstahl, etc.), we note Nazi militarization and might, which after a while are easily relegated to “the past.” Photographs throughout the play’s album note the Nazi flag, Hitler salute and SS uniform as a common fact of life lived at that time. Indeed, Hitler’s politics became the breath of life itself and all aspects of the German people’s existence and happiness were intertwined with Nazism, Hitler’s “great” leadership, his conquests, economic prosperity, and the ready identification with all of this by the average German. This was so until things went terribly sour and German war losses multiplied.

However, the Third Reich’s asserting ordinariness and commonality, when in fact it was anything but, is one of the concepts the archivists deal with throughout their journey to organize the photographs, categorize them and analyze what they are looking at in the photo album of the SS’ lives at Auschwitz.

The playwrights introduce us to the archivists in the second scene. It is then Rebecca Erbelding (Elizabeth Stahlmann), first reads the letter from the Lieutenant Colonel notifying the museum that an album with photographs from Auschwitz that he possesses might be of import. From that juncture on, we become engrossed in the archival journey as the researchers, experts and others delve into the album and attempt to understand it. Curiously, there are no photos of the victims and prisoners of Auschwitz.

As they take on the difficult task and uncover details through trial and error, eventually, researchers bring together the puzzle pieces which explain the photographs and identify the SS officials and the various workers up through the hierarchy, who helped Auschwitz seamlessly function. Clearly, Auschwitz was a huge endeavor that contained an industrial complex and barracks for laborers, housing for guards and administrators alike, and a killing machine and ersatz assembly line of death.

After pinpointing the owner of the album as Karl Höcker, who moved his way up to become the administrative assistant to the head of Auschwitz., the archivists (who also bring to life Karl Höcker and others via dramatization), gradually explore the lifestyle of those in the photographs. These include the SS guards, top brass, doctors, various secretaries (Helferinnen, who were in communications, etc., and held jobs at the camp), staff and others having meals, relaxing at a nearby resort and more daily activities.

None of the photos show the functions of Auschwitz, the prisoners, victims or crematoria. All is pleasant and reflective of the wonderful world that Hitler spoke about bringing to mankind after the “vermin” were removed. That the Helferinnen were photographed surprised a number of researchers who wondered if the young women knew about the gas chambers in the camp or smelled the acrid air of burning flesh in the crematoriums. After denials and relatives probing and finding innocence, what the women knew is later answered by one of the secretaries who was at Auschwitz. She was questioned after the war. Charlotte Schunzel stated she and the other women recorded how many were sent to hard labor and how many were sent to SB, “special treatment,” a euphemism for the gas chambers.

The archivists pin down the identity of the SS officers and high command in the photographs, one of whom was the notorious “Angel of Death,” Dr. Menegele. Another is the commandant who set up Auschwitz-Birkenau, Rudolph Höss. The researchers determine that the photos are like selfies that reveal the happy life of Karl Höcker (Scott Barrow), who would have been a “nobody” if he had not joined the Nazi party in 1937 and arrived at the camp in 1944, just in time to help “process” the thousands of Jewish Hungarians (350,000), who rode in trains three days, only to be murdered in gas chambers after they arrived.

Kaufman and Gronich seize our interest especially when actors take on historical personages, relatives of the SS, survivors, researchers, historians and others. in view of the audience, actors create Foley sound effects to usher in events and accompany Erbelding, Judy Cohen (Kathleen Chalfant), Charlotte Schunzel (Nemuna Ceesay), Tilman Taube (Jonathan Ravlv), Melita Maschmann (Erika Rose), Rainer Höss (Charlie Thurston), Peter Wirths (Grant James Varjas), and others as they uncover bits of information and puzzle together what is happening in each photograph.

The global attention the album receives (revealed by projections of headlines), brings new interest and revelations, some by grandchildren of the SS who are horrified to see uncovered aspects of their relatives they didn’t want to imagine. These aspects have been kept hidden from families out of shame and especially to avoid accountability. Perpetrators of murder and the accomplices to murder are still being located and held to account, even as recently as the last two years. Murderers and the complicit and culpable had a great need for covering up their crimes, as long as they were alive.

Another revelation comes from Holocaust survivor Lili Jacobs, who contacts archivists, as a result of the press reports. She had been holding on to an album she uncannily found of 193 photographs of the Hungarians arriving on the trains, all of whom were “processed” by the SS and high command in the photos. After she donates her album (it contains pictures of herself and family taken by the SS in the camp the day she arrived from Hungary), the researchers are able to solve the dates of the mystery of one photo which shows all the SS, high command and workers celebrating at Solahütte (a resort), where Karl Höcker occasionally rewarded the SS guards, workers, Helferinnen etc., when they did something special.

One example is given when guards prevented an escape by killing four prisoners. Administrator Höcker rewarded them for their “courage” by sending them to Solahütte for a few days.

Previously, the archivists couldn’t understand what and why the large group of camp officials, workers, drivers, Auschwitz staff, referred to by one archivist as the “Chorus of Criminals,” were photographed celebrating. However, through interviews with experts, and piecing together the facts, they divine why the entire group of Auschwitz Nazis standing and smiling, were enjoying the accordion music in one, fine, inclusive photograph, from the top brass in the front, to the lowly staff standing on a hill in the back.

With the evidence of the two albums together, archivists complete the full story of murderers and victims. The victims in Jacobs’ album were those who arrived in train transports from Hungary. The photographs included photographs of Lili and her family and her rabbi, right before they were separated into the lines for labor camp and gas chambers. In Höcker’s album, the administrator assembled and photographed the “Chorus of Criminals'” photograph for a vital reason. The murderers celebrating at Solahütte were congratulating themselves. They had successfully finished a job well done, the massive operation, processing Hungarians, dividing and selecting, so that 350,000 could be exterminated, among them Lili’s parents and two younger brothers.

Through their research, archivists discovered that Lili arrived one day after Höcker arrived at Auschwitz. He most probably received a career bump up to administer the massive “Hungarian Project.” In light of Lili’s discovery and sharing it with the archivists at the museum, she and they “get the full picture.” She sees the identity of the men who murdered her family. Finding the album of herself in the tie in with the album of the SS who ran the camp is an extraordinary sequence of events that is beyond coincidence. For her, the discovery is mystical and divinely spiritual.

Ironically, in Here There Are Blueberries, the victims that the Holocaust Memorial Museum has been so diligent about uplifting and respecting are not the only ones to be considered in studying and understanding the Holocaust. The innocent victims, indeed, were the extraordinary ones in Hitler’s politics that had infiltrated into the bones of the German people, but not the bones of the innocent ones ravaged by acts of the brutal tragedy delivered for the “good of the nation” in its lust for domination. The victims’ impossibly painful stories of survival or loss, escape, surrender, the trauma, and the horror, shock, astound and enrage.

That the ones who perpetrated murder and genocide were able to do it day in and day out as a matter of routine, a job to be done, exemplifies the normalization and internalization of a monstrous political attitude. That attitude that the SS, many Germans and surrounding cultures (i.e. Austria) adopted as right and true, a way of being, a way to live one’s life, which necessitated that others bleed and die for it as a general social good, is evidenced throughout Hocker’s album of photographs of the SS’s smiling faces as they perform daily activities.

It is this above all that Kaufman and Gronich bring to the table and highlight like no other work, with the exception of Martin Amis’ novel Zone of Interest, about the life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, which was recently made into a film, directed by Jonathan Glazer. However, unlike Zone of Interest, Kaufman and Gronich don’t include responsive photos to the crematoria. All photos of camp function and purpose are missing. Only in Lili Jacobs’ companion album do we note the horror of the transports and the photos of her rabbi, her parents and siblings who died.

The photos of those accountable for all of the activities at Auschwitz, their reason for being there-to kill, oppress, subjugate and promote the war effort-is implicit. Their very images in the photographs stink with the noisome odor of the gas chambers. The absence of the victims and any evidence of the killing machine, a final realization of the archivists who investigate the album, if anything, incriminates all of the SS officers even more in their guilt. If they were innocent and in the right, why did Höcker need to edit out the buildings of the killing machine, the prisoners and torturing that happened in the labor complex? Why did he need to present his album of “happy days are here again?” when obviously the smoke of the burning had to be hidden?

In the archivists’ explorations they learned the backgrounds of the SS running the camp were ordinary-former clerks, bank tellers, confectioners, teenage girls. We are prompted to ask what separates these murderers and accomplices to murder from the rest of us? Stating the Nazis were monsters allows us the luxury to say “we are not like them.” It dupes us to think we would never be caught up as these were, convinced in the rightness of their actions. This is a dangerous attitude. Indeed, playwright Kaufman reflects the overriding theme of Here There Are Blueberries when he states that “the Nazis were not monsters-they were normal people who did monstrous things.”

How are political cults convinced of their rightness convinced to murder for the right? How did the January 6th insurrection fomented by a sore loser with revenge on his mind to punish his VP because he didn’t do what “was right” happen? Are there any elements that might be compared? This amazing play is filled with parallels to our time, as it raises profound questions about our humanity. For that reason, as well as the fine dialogue and overall presentation and ensemble work, one should see this play.

Here There Are Blueberries runs 90 minutes with no intermission at NYTW on 4th St. between 2nd and the Bowery. Don’t miss it.

‘Paradise Square,’ a Breathtaking, Exquisite, Mindblowing, American Musical

First there was Lin Manuel Miranda and Alex Lacamoire’s Hamilton which codified our founding fathers through a current lens and brought them into living reality with a new understanding of the birth of our nation. Now, there is the musical Paradise Square which brings to vivid life the embodiment of the American Dream during the Civil War, 1863, after President Lincoln instituted the Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves.

The phenomenal, complex musical is nothing short of a heart-rending emotional shakedown for feeling Americans at this precarious time in our history. Currently, it runs at the Barrymore Theater creating buzz and furor through word of mouth. With Book by Christina Anderson, Craig Lucas and Larry Kirwan (conceived by Kirwan with additional music inspired by the songs of Stephen Foster), music by Jason Howland and lyrics by Nalthan Tysen & Masi Asare, the production’s success is a collaborative effort, and that is a testament to the individuals whose creativity and flexibility brought the spectacular, dramatic elements together coherently with symbolic, thematic power.

With the actors, Alex Sanchez’s Musical Staging, Bill T. Jones genius choreography and the enlightened and anointed direction of Moises Kaufman, the demonstrated will and determination to make this production leap into the firmament cannot be easily dismissed or inconveniently dispatched for whatever reason. (reference Jesse Green of the New York Times)

The setting of this thematically current musical takes place in a slum of cast offs and immigrants who are making the American experiment their own and bringing equanimity to New York City like never before. On a patch of ground in the Five Points that is home to saloon Paradise Square, proprietor Nelly O’Brien (the incredible Joaquina Kalukango who champions the character and all she symbolizes), has created her own version of Eden with her Irish American husband Willie O’Brien (the superb Matt Bogart). There, all are worthy and respected.

Nelly exemplifies the goodness and hope of our American glory and opportunity through hard work, faith and community. Born in the saloon from the oppressed, her father a slave who escaped to the North via the underground railroad, her mixed race marriage is uniquely blessed. It is just like that of her sister-in-law Annie O’Brien Lewis (the superb Chilina Kennedy), married to Reverend Samuel Jacob Lewis (the equally superb Nathaniel Stampley), a Quaker and underground railroad stationmaster. Both couples have prospered, are decent and shed truly Christian light and love on all they meet.

Nelly, the principals and company present life in “Paradise Square,” in the opening song. This is the seminal moment; book writers establish the overarching theme, the hope of America, an Edenic place where all races and creeds get along without division or rancor.

“We are free we love who we want to love with no apology. If you landed in this square then you dared to risk it all, at the bottom of the ladder, there’s nowhere left to fall,” Nelly sings as the patrons echo her and dance. The opening moments clarify what is at stake for Nelly and all who pass through the doors of the saloon. It is a safe haven, where in other areas of the city, the wealthy uptown, for example, these “low class” immigrant whites, and blacks are unwanted and unwelcome. It’s a clear economic divide which grows more stringent as the war’s ferocity intensifies and money becomes the way in to safety and the wall that directs the Irish and other immigrants to the Civil War’s front lines; one more hurdle to overcome after surviving cataclysms and impoverishment in their home countries.

Of course, the symbolic reference is not lost and we anticipate that Eden achieved is not Eden sustained, though Nelly has managed to effect her safe place during the first three years of the war. What keeps her energized is her spirit of hope and her dream which she intends to promote throughout the war until her husband, Captain O’Brien of the 69th regiment of fighting Irish, returns once the Union army has won its righteous cause. Nelly and Willie’s touching song and flashback to their first meeting reveals that they are color blind (“You Have Had My Heart”), and move beyond race and ethnicity to the loving, Edenic ideal which uplifts spirit over flesh and lives by faith rather than sight.

At the top of the production Nelly shows a black and white projection of the modern Five Points and the place where her saloon used to be, as she merges the present with the past and suggests she is relating her story, a story that won’t be found in history books. It is a “story on our own terms,” that exemplifies unity in a community of races and religions bounded by love, concern and financial equality as all struggle to make ends meet, and with each other’s help, get through the tribulations of the Civil War’s impact on their lives.

The exceptional opening song and dance number resolves in a send off of Willie O’Brien and ‘Lucky Mike Quinlan’ (Kevin Dennis) to the battlefield. Both rely on an inner reservoir of faith and Irish pluck, knowing the prayers of the Reverend and all in Paradise Square go before them. The vibrant titular number is uplifting and beautiful as it highlights the American experiment which British royals doomed to failure and Benjamin Franklin ironically stated-our government is “a republic if you can keep it.”

Though the republic has been divided in a Civil War, folks like those who come to Nelly’s saloon believe in nation’s sanctity and are keeping the dream alive, if the South has abandoned it. Indeed, as the book writers suggest, the immigrants and those of passion and heart will hold the dream in their hearts and attempt to manifest its reality because freedom, respect and equanimity is worth dying for. With irony the book’s writers reveal this is something the wealthy do not believe because they don’t have to. Their world rejects the values and ideals of those who people Paradise Square. Without principles worth dying for, the hearts of the Uptowners are filled with greed for power and money. These are the passions that drive the rich, symbolized in the scenes with Party Boss and political strategist Frederic Tiggens (the excellent and talented John Dossett).

Complications develop when Annie’s nephew Owen (the wonderfully talented A.J. Shively), travels from Ireland at the same time that Washington Henry (the wonderfully talented Sidney DuPont), escapes with Angelina Baker (Gabrielle McClinton). Traveling on the underground railroad from Tennessee, Henry arrives in New York City without his love, whom he waits for, braving the dangers of capture. Owen and Henry joined by Annie and the Reverend, a stationmaster on the underground railroad who receives Henry, all sing (“I’m Coming”). The young men, like hundreds before them, seek freedom and prosperity believing in the opportunities afforded by the shining city.

Reverend Samuel alerts Annie that Henry escaped from border state Tennessee which is not covered in the Emancipation Proclamation. Thus, when Henry says he can’t go to Canada, but must wait for Angelina Baker, the Reverend fears for all of them. Nevertheless, guided by faith and Nelly’s extension of grace to Washington Henry, their community stands together and Owen and Henry bunk congenially in a tiny room above Paradise Square saloon.

Additionally, stranger Milton Moore (Jacob Fishel), arrives in their society to beg Nelly for a job. Moore, an excellent piano player with a drinking problem, appears legitimate, so Nelly makes a bargain with him and arranges for Owen, Henry and Moore to create dance and song entertainments to earn their keep. The dancing and singing to a cool multi-ethnic version of “Camptown Races” effected by Henry and Owen who are friendly competitors at this juncture, show the prodigious singing and dancing talents of Shively and Dupont. Guided by Bill T. Jones’ brilliant, energetic and enlightened choreography, the dancing in this production is thematic and symbolic, with unique stylized flourishes that shine a light on the exceptional talents of the principals and the ensemble.

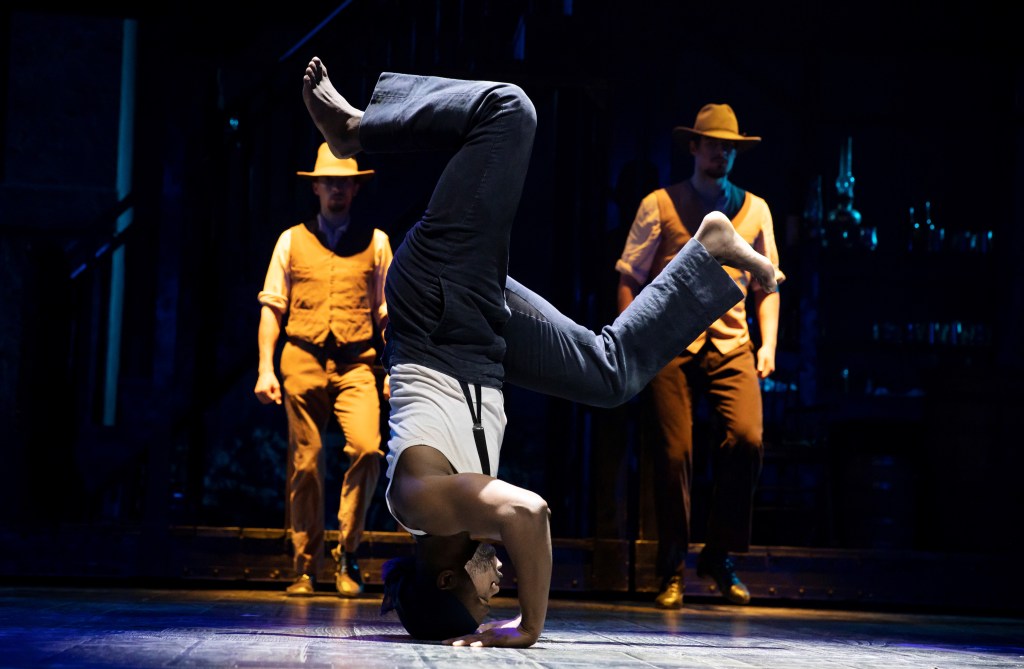

Jones showcases the dances with ethnic cultural elements: for Shively and his group-Irish step dancing; for DuPont-Juba African American dancing that evolved from plantation life. Jones’ wondrous evocations are present throughout. When Henry sings “Angelina Baker” we revert to the plantation where both met. Profoundly rendered through Jones choreography and musical staging (Alex Sanchez), the ensembles’ stylized movements evoke the field slaves soul burdened and bowed, as two plantation overseers tap dance the repetitive torment and the beats of slavery’s oppression and pain. Just incredible!

Uptown Party Boss Frederic Tiggens (the excellent John Dossett) is the villainous snake, whose intent is to divide voters, secure political power and keep wages low by targeting the haven of equanimity, Paradise Square. As a disrupter, he focuses on a “divide and conquer” strategy. Stoking division when the opportunity arises, he is hell bent on destroying Nelly’s prosperous Eden which threatens his political power block. Thus, he foments resentment between the Irish and the blacks when he discovers that the Reverend doesn’t fire a worker to give a job to ‘Lucky Mike,’ a war amputee abandoned by the government he fought for. (“Bright Lookout,” “Tomorrow’s Never Guaranteed.”).

Enraged at the injustice of not being hired by Reverend Samuel who can’t do what he wants or he will be fired himself, ‘Lucky Mike’ becomes the pawn of Tiggens, who exploits his anger instead of helping him. Expressing the plight of many returning vets then and now, Mike’s anger grows into a raging fire with no outlet until it finally explodes in violence. Tiggens’ trouble-making continues with his connections serving financial writs on Nelly and Paradise Square that must be paid off. When she confers with family about raising money, Owen contributes his cultural grace, suggesting a dance festival competition like they had in Ireland. With the festival Nelly will raise enough to pay off the fines. Once again, Nelly and family resilience and hope shine through the darkness of Tiggens’ political machinations to overwhelm them.

Meanwhile, the Reverend is informed by his Quaker friends that Henry has killed his plantation master in Tennessee and is wanted for murder. The Reverend tells Annie who insists she will accompany him and Henry to the next station on the railroad. The song “Gentle Annie” is a humorous revelation of their marriage: Annie’s feisty character tempered by Samuel’s peaceful nature, their shared values and the closeness of their relationship. Kennedy and Stampley give authentic, spot-on performances that solidify one more link in the ineffable chain of love that helps make Paradise Square (the saloon and the production) a place of unity and grace.

A strength of this musical is that the dramatic tension increases and doesn’t let up for a minute. The arc of development in conflicts and intricate, complex themes shows Nelly’s Paradise Square, like Lincoln’s Union strained and stressed. As Tiggens tightens the financial noose on Nelly’s Eden, the announcement of the War Draft threatens the immigrants. Men between the ages of 25-45 must serve, unless they pay $300 dollars to exempt themselves. Lincoln’s conscription is a desperate attempt to revitalize the fight; the Union is on the verge of collapse and the American experiment is in grave jeopardy. Nelly’s dream and Lincoln’s hope of a democratic union run on parallel tracks along with the underground railroad.

For the blacks, the idea that people had inalienable rights and could live together with respect, dignity .and equanimity as a community, the idea that people themselves had the power to sustain such a republic, was keenly felt. Blacks wanted desperately to fight against the Southern oppressors, but were forbidden. (“I’d Be a Soldier”). The Irish, like Owen and the other immigrants, were looking for a better life not war (“Why Should I Die in Springtime?”), but they are ground down by their poverty and question the efficacy of dying for a cause they didn’t create and can’t afford to get out of.

When Owen and the ensemble of Irishmen/immigrants and Henry and the ensemble of blacks sing these numbers, the power of the lyrical music drives home the differences. Both groups embrace the American ideal but are being denied achieving it in reality. As the anger of ‘Lucky Mike’ gains advocacy, it fuels fear in Owen because, for him, the Draft is unjust; he doesn’t have the money. Nelly, for the first time tells ‘Lucky Mike’ to leave her bar as he tries to rally protestors for his (Tiggens propagandized) cause.

As Nelly inspires and encourages her patrons telling them they must not “let the draft break us, that’s what those Uptown bastards want,” an Irishman comes with news that does bow her, Captain Willie O’Brien’s death. But for the Reverend and Annie (“Prayer”), and Nelly’s moral imperative to maintain the saloon’s mission, Nelly would break. As she attempts to gain comfort and inner resolve, the Reverend and Annie confront Henry about murdering his master. In the incredible “Angelina Baker” sung by DuPont with the dancers evoking the Tennessee plantation terrors, we understand his justification for killing.

By the end of Act I, Nelly, Annie, the Reverend, Owen, Henry and the patrons stand on a precipice as the war and malevolent forces threaten to overcome them. Nelly sings, “I keep holding on to hope for a world just out of view, but that hope I have comes at a cost and the cost comes due.” But it is in the song’s refrain that Joaquina Kalukango sings for the ages. Nelly prays with grace and dignity: “Heaven Save Our Home.” Kalukango’s Nelly becomes the intercessor who has made the ultimate sacrifice. All those she loves in Paradise Square are in jeopardy. Her Eden hangs by a spider’s web. As we identify with her prayer, Kalukango’s Nelly stands in the gap for all who are threatened by war and oppression, or unseen forces that would trammel down the sanctity of life. In her portrayal, as she attempts to touch the heart of God, she enthralls our humanity. It is what live theater is all about.

In the transition to Act II, book writers take us to wealthy Uptown New York City. The set changes from the dark saloon, three level platforms, box cages and hard scrabble lines and angles to light, airy, plush furniture in a luxurious drawing room where the wealthy Mr. Tiggens, Amelia Tiggens and Uptown women are being entertained by Milton Moore. Moore presents new versions of songs he culturally appropriated from those he’s heard sung by immigrants and blacks in the Five Points. The scene brings heartbreak at the revelation that “Milton Moore” has been the cover for Stephen Foster (Jacob Fishel).

In a fascinating and ingenious twist in the arc of development, Foster, revitalized by his time in Paradise Square, exploits its greatness, democracy and vibrancy. He brags to Tiggens about his inspired time and unwittingly reveals what Nelly and the others plan. The scene is another dynamo that spills over into chaos when Foster returns to Paradise Square and confronts Nelly, who is arranging to financially save her saloon, Owen and Henry with the dance festival. Foster’s betrayal is a stinging blow. Though he apologizes and attempts to salve the wound by telling Nelly she encouraged his reformation, the danger he reigns down on them is unforgivable. Too late, she ejects him; but the damage has been done. All that is left is to hope that the dance festival brings in enough money to save her saloon and Owen and Henry.

The dance comes off in, another incredible scene with Jones’ amazing choreography front and center as Shively’s Owens and DuPont’s Henry compete, this time not so congenially. There is a winner. You’ll just have to see the show to find out. But the competition doesn’t have the desired effect. Subsequently, New York City undergoes its own class war as the immigrants go uptown in a rage to protest. The NYC Draft Riots, a well documented catastrophic debacle (50 buildings burned, 119 people dead) with destruction, death looting and burning lasts for three days until the US army quells the rioting. As the rioters set fire to Paradise Square, Kalukango’s Nelly confronts them and delivers a message (“Let it Burn”) that defies description in power and spiritual glory.

“Inside this little building is a rare and special lot; we somehow found each other and look what that has wrought; a place you are afraid of, a world you’ll never know; you can take it in a flash; you can burn it down to ash and then out of ash we’ll grow; if you think we’ll run away, you’ve got a lot to learn we are stronger than your fire, and I say let it burn.”

Nelly realizes her Edenic dream continues in greater power without a building to house it. Thus, she gives up the one thing she worked incredibly hard to keep with the knowledge that Paradise Square and all it symbolizes to her is within her soul forever. It is for future generations to manifest and make her Edenic dream a reality.

How the creative team and Kalukango deliver this moment is miraculous. What the show kindles in those receptive to its messages and themes heals, strengthens and affirms. It is the glory of what our country can be in the resilience of the human spirit that uplifts freedom from the boot of financial, moral, ethical oppression and evil in all its forms.

As I watched this production, I couldn’t help but align its “dangerous” democratic themes to events around the world and in our own country. Nelly’s message is the Ukrainians’s message to Vladamir Putin in his unjust war and attempt to destroy Mariupol and other Ukrainian cities with his Stalinist communist terror which cannot succeed. Similarly, I thought of the ultra extremist right wing politicos in the U.S., who would make women heel to their oppression by criminalizing abortion to the point of making it tantamount to homicide, while sanctifying, legitimizing rape. (The rapist becomes a father, bonded to the child and mother.)

The Supreme Court in attempting to overturn settled law, effects a second insurrection more damaging than that of the coup conspiracy by Donald Trump and QAnon Republicans on 6th January. When Kalukango’s Nelly sings her cries for safety and freedom, affirming both by the conclusion, she intercedes for all Americans who still believe with Lincoln in government of, by and for the people. The lrich minority are incapable of hearing such cries from the spirit. They only want to rule like despots.

The values and themes heightened in Paradise Square are truly Christian, American and democratic. The production is a vital happening during a time when political terrorist forces inside our country conspire with foreign adversaries to nullify our constitution and foundations of government based on self-evident truths in our Declaration of Independence; that all are created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights. There is no musical on Broadway today which best represents the American spirit and ideals.

If this does not sound like something you might like, then especially go see it. For tickets and times see their website: https://www.paradisesquaremusical.com/