Blog Archives

‘The Burning Cauldron of Fiery Fire,’ Anne Washburn’s Challenging, Original Play

Known for its maverick, innovative productions, the Vineyard Theatre seems the perfect venue for Anne Washburn’s world premiere, The Burning Cauldron of Firey Fire. Poetic, mysterious and engaging, Washburn places characters together who represent individuals in a Northern California commune. When we meet these individuals, they have carved out their own living space in their own definition of “off the grid.” Comprised of adults and children, their intention is to escape the indecent cultural brutality of a corrupt American society, where solid values have been drained of meaning.

Coming in at 2 hours, 5 minutes with one 15 minute intermission, the actors are spot-on and the puppetry engages. However, the play sometimes confuses with director Steve Cosson’s opaque dramatization of Washburn’s use of metaphor, poetry and song. More clearly presented in the script’s stage directions, the production doesn’t always theatricalize Washburn’s intent. Certainly, the themes would resonate, if the director had made more nuanced, specific choices.

The plot about characters who confront death in their commune in Northern California unfolds with the stylized, minimal set design by Andrew Boyce, heavily dependent on props to convey a barn, a kitchen and more. The intriguing lighting design by Amith Chandrashaker suggests the beauty of the surrounding hills and mountains of the north country where the commune makes its home.

The ensemble of eight adult actors takes on the roles of 10 adults and 8 children. Because the structure is free-flowing with no specific clarification of setting (time), it takes a while to distinguish between the adults and children, who interchange roles as some children play the parts of adults. The scenes which focus on the children (for example at the pigpen) more easily indicate the age difference.

The conflict begins after the members of the commune burn a fellow member’s body on a funeral pyre to honor him. Through their discussion, we divine that Peter, who joined their commune nine months before, has committed suicide, but hasn’t left a note. Rather than to contact the police and involve the “state,” they justify to themselves that Peter wouldn’t have wanted outside involvement. Certainly, they don’t want the police investigating their commune, relationships and living arrangements which Washburn reveals as part of the mysterious circumstances of this unbounded, “bondage-free,” spiritual community.

Nevertheless, Peter’s death has created questions which they must confront as tensions about his death mount. Should they reburn his body which requires the heat of a crematorium to reduce it to ashes? After the memorial fire, they decide to bury him in an unmarked grave, which must be at a depth so that animals cannot dig up his carcass. Additionally, if they keep any of Peter’s belongings, which ones and why? If someone contacts them, for example Peter’s mother, what story do they tell her in a unity of agreement? Finally, how do they deal with the children who are upset at Peter’s disappearance?

We question why they feel compelled to lie about Peter’s disappearance, rather than tell the truth to the authorities or Peter’s mom, even if they can receive her calls on an old rotary phone. Thomas, infuriated after he speaks to Peter’s mom who does call, tells her Peter left with no forwarding address. After he hangs up, Thomas (Bruce McKenzie) self-righteously goes on a rant that he will tear down the phone lines.

When Mari (Marianne Rendon) suggests they need the phone for emergency services, he counters. “Can anyone give me a compelling argument for a situation in which this object is likely to protect us from death because let me remind you that if that is its responsibility we have a recent example of it failing at just that.”

Indeed, the tension between commune members Thomas, Mari, Simon (Jeff Biehl), Gracie (Cricket Brown) and Diana (Donnetta Lavinia Grays) becomes acute with the threat of outside interference destabilizing their peaceful, bucolic arrangements. Washburn, through various discussions, brings a slow burn of anxiety that displaces the unity of the members as they work to hide the truth. What begins at the top of the play as they burn the body in a memorial ceremony that allows Thomas and the group to take philosophical flights of fancy, augments their stress as they avoid looking at hard circumstances.

Fantasy and reality clash also In the well-wrought scene where the actors portray the children moving the piglet they believe is Peter when it reacts to Peter’s belongings, specifically, a poem it chews on. Convinced Peter has been reincarnated and is with them, they take the piglet staunching their upset at Peter’s death by reclaiming and renaming the piglet as the rescued Peter. Rather than to have explained what happened, the commune members allow the children to believe another convenient lie.

This particularly well-wrought, centrally staged scene of the children in the pigsty works to explicate the behavior of the commune members. They don’t confront Peter’s death and don’t allow the children to either. The actors captivate as they become the children who relate to the invisible mom Lula and her piglets with excitement, concern and hope. It is one of the highpoints of the production because in its dramatization, we understand the faults of the commune. Also, we understand by extension a key theme of the play. Rather than confronting the worst parts of their own inhumanity, people close themselves off, escape and make up their own fictional worlds.

Washburn reveals the contradictions of this commune who parse out their ideals and justify their actions “living away from society.” Yet they cannot commit to this approach completely because of the extremism required to disconnect from civilization. As it is, they have a car, they do mail runs and sometimes shop at grocery stores. At best their living arrangement is as they agree to define it and as Washburn implies, half-formed and by degrees runs along a continuum of pretension and posturing.

The issues about Peter’s death come to a climax when Will (Tom Pecinka), Peter’s brother, shows up to investigate what happened to Peter. Washburn ratchets up the suspense, fantastical elements and ironies. Through Will we discover that Peter was an estranged, trust-fund baby who will inherit a lot of money from his grandmother who is now dying. Ironically, we note that Mari who claims she had an affair with Peter and dumped him (the reason why he “left”), is willing to have sex with Will. They close out a scene with a passionate kiss. Certainly, Will has been derailed from suspecting this group of anything sinister.

Also, Will is thrown off their lies when he watches a fairy-tale-like playlet, supposedly created by Peter and the children that is designed to lull the watcher with fanciful entertainment.

In the fairy tale a cruel king (the comical and spot-on Donnetta Lavinia Grays), prevents his princess daughter (Cricket Brown) from marrying her true love (Bartley Booz), also named Peter. The bad king thwarts Peter from winning challenges to gain the princess’ love. Included in the scenarios are puppets by Monkey Boys Productions, special effects (Steve Cuiffo consulting), the burning cauldron of fiery flames with playful fire fishes proving the flames can’t be all that bad, and a beautiful, malevolent, dangerous-looking dragon who threatens.

Once again creatives (Boyce, Chandrashaker and Emily Rebholz’s costumes) and the actors make the scene work. The clever, make-shift, DIY cauldron, puppets and dragon allow us to suspend our judgment and willingly believe because of the comical aspect and inherent messages underneath the fairy-tale plot. Especially in the last scene when Peter (the poignant Tom Pecinka), cries out in pain then makes his final decision, we feel the impact of the terrible, the beautiful, the mighty. Thomas used these words to characterize Peter’s death and their memorial funeral pyre to him at the play’s outset. At the conclusion the play comes full circle.

Washburn leaves the audience feeling the uncertainties of what they witnessed with a group of individuals eager to make their own meaning, regardless of whether it reflects reality or the truth. The questions abound, and confusion never quite settles into clarity. We must divine the meaning of what we’ve witnessed.

The Burning Cauldron of Fiery Fire runs 2 hours 5 minutes with one 15-minute intermission at Vineyard Theatre until December 7 in its first extension. https://vineyardtheatre.org/showsevents/

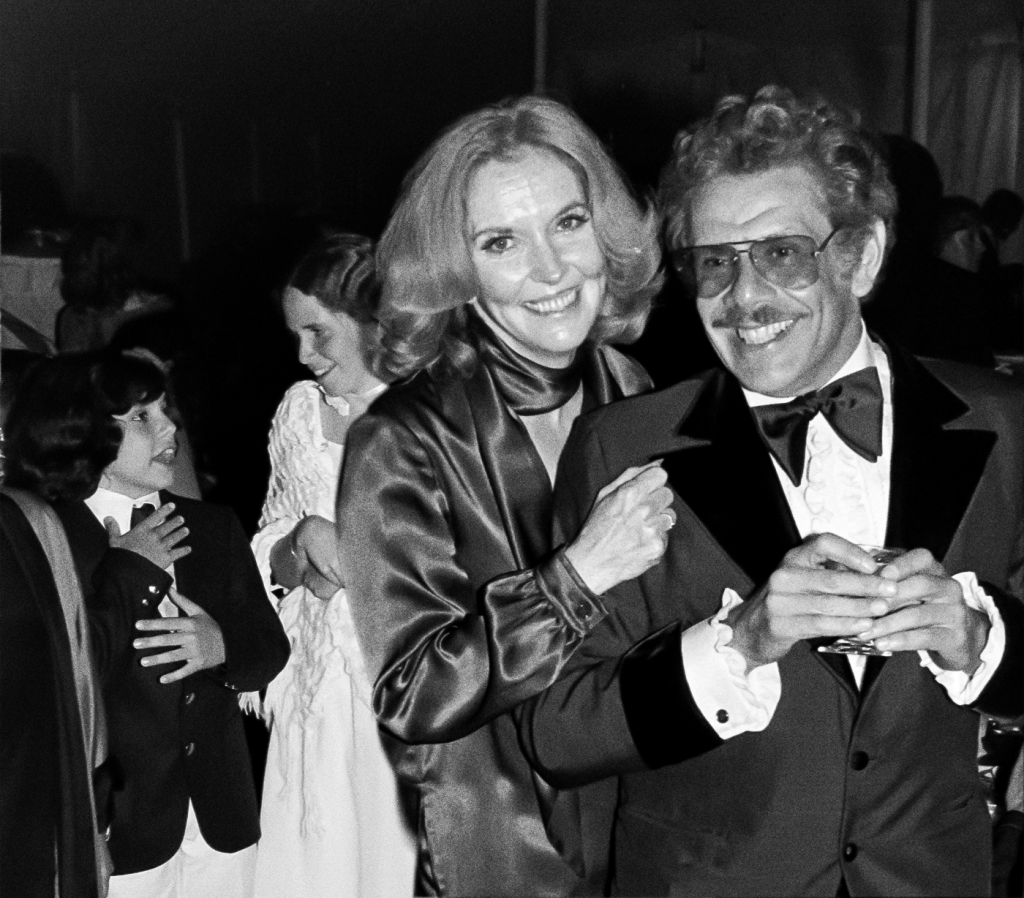

‘Stiller & Meara: Nothing is Lost’ Ben Stiller Honors his Parents’ Legacy @NYFF

In the Q and A after the screening of his documentary about his parents, Ben Stiller quipped “…my parents who couldn’t be here, I hope they’re OK with it. There’s no way to really check on that. I hope the projector doesn’t break.” Well, the projector didn’t break and no rumbling of thunder, falling lights or crashing symbols happened. So, they must be “OK” with the film. Certainly, the audience showed their pleasure with long applause and cheers. In one section near me they gave a standing ovation for Stiller & Meara: Nothing is Lost.

Ben and Amy Stiller’s film collaboration about their parents, directed by Ben Stiller, screened in its World Premiere in the Spotlight section of the 63rd NYFF. Employing their experience in the entertainment industry, Ben Stiller (comedian, actor, writer, director, producer) and sister Amy Stiller (comedian, actress) explore their parents’ impact on each others’ lives and careers to then influence their children’s lives. In the latter part of the film we note this multigenerational family project also includes Stiller’s wife, Christine Taylor Stiller; and his children Ella and Quinlin Stiller.

However, in order to begin to tell the story of three generations of Stillers, the siblings reach back before their parents’ marriage and their births. From that vantage point they first examine how Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara met. Then they explore how Jerry and Anne shared their interests and talents. Recognizing that they could work together, they created the successful comedy duo that Ed Sullivan first invited on his show in April of 1963.

Enamored of them as performers and people because their ethnic and religious backgrounds mirrored Sullivan and his wife’s, Stiller and Meara returned to the show again and again. Because they were funny and made their comedy relationship/marriage sparkle, they were a hit. In reflecting on this, Stiller shows a number of clips from the archives and even meets with Steven Colbert at the theater named for Ed Sullivan (the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York City). The two of them discuss what it must have been like to audition live as unknowns and hit the ground running on a nationally aired program that millions watched every week.

Using clips from that show, and other TV shows, films, theater and more, Stiller cobbles together a delightful, honest, intimate and funny chronicle of his parent’s marriage on and off camera. The director delves into their unique styles and talents which gave them their comedy act. Stiller insists that his dad struggled to be funny and constantly had to work at it. On the other hand his mom found humor naturally and could “ad lib” humorous riffs effortlessly. His dad so admired this about her talent.

Importantly, Stiller captures the history of that time which contributes to our understanding of the nation’s social fabric. Their work historically reflected 60s humor that appealed then but still has an appeal today. Though they worked together and refined their act for years, eventually, they worked separately. Stiller discusses how and why this happened. Essentially because they wanted different things and were their own people, they tried their own TV shows. Then other opportunities came their way.

Humorously, his documentary reflects his parents’ relationship so it became difficult to know when the comedy act ended and where their real marriage began. Perhaps it was a combination of all and/or both. Since his Dad saved tons of memorabilia (photos, programs, reviews, clips, tapes, videos, home movies) from their lives, Ben makes good use of these artifacts.

Additionally, Stiller reveals the more personal and intimate aspects of himself and Amy growing up with his parents. Principally, he uses this perspective to show the parallels with his parents’ relationship as he briefly looks at his marriage with his wife and relationship with his children. One segment has interviews with Christine, Ella and Quin. Importantly, he relates their perceptions with his attitude toward his parents growing up.

This project that began after Jerry Stiller died in 2020 and took five years to complete saw Stiller and his wife Christine through a separation and getting back together again. Stiller looked at how his parents kept their marriage together through the pressures of performing together. That reflection influenced him in his relationship with Christine.

As Stiller worked on selecting how to approach the film with the material left to him and his sister, a concept came to him about legacy. Indeed, the documentary forms a portrait of a family whose legacy of humor, creativity and prodigious hard work has passed down from generation to generation.

In short the film reveals that Stiller and his sister Amy are humorous acorns that don’t fall far from their ironic and funny parental oaks. Amy and Ben’s sharp wit from his mom and dogged perfectionism from his Dad, come into play in the creation of this film. Mindful that all of his family’s lives are in his hands, with poetic consideration Stiller’s profile of those most dear to him is heartfelt, balanced and emblematic of a gentler, loving, kinder time. We need to see examples of this more than ever. To read up on the film description and to see additional photos, go to the NYFF website. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/stiller-meara/

An Apple Original Films release, look for Stiller & Meara: Nothing is Lost in select theaters on October 17, 2025. It receives wide release on October 24th.