Blog Archives

‘Here There Are Blueberries,’ No Evil. Just Ordinary, Enjoyable Routines.

Here There Are Blueberries, now in its third extension at New York Theatre Workshop, is a many-layered, superb production running until June 30. Stylized and theatricalized as a quasi-documentary that travels back and forth from present to past to present by enlivening characters in various settings, the play unravels the mysteries centered around an album of 116 photographs taken at Auschwitz. Though the album has no photographs of the victims to be memorialized, it eventually is donated to archivists at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, by a retired U.S. Lieutenant Colonel.

Based on real events, interviews, extensive research and photographs rarely seen of the infamous concentration camp from another perspective, the play follows archivists who shepherded the photographic artifacts toward a greater understanding of the political attitudes and the daily routines of the people who ran the camp. Written by Moises Kaufman and Amanda Gronich, and directed by Moises Kaufman, Here There Are Blueberries is a salient, profound work that has great currency for our time.

With expert projection design by David Bengali, Derek McLane’s scenic design, which suggests the archivists’ workplace, and Kaufman’s minimalism, characters/historical individuals step forward to bear witness, like a Greek chorus, to speak from the ethereal realms of history. The play which has some Foley sound effects for purposes of interest, dramatizes scenes which hover around a concept. All of the fine artistic techniques by Dede Ayite (costume design), David Lander (lighting design), Bobby McElver (sound design), further the plays probing themes which examine questions the researchers ask about those who murdered and why they murdered. As the drama poses questions to its audience and itself, some, the play answers. Others, the audience must answer for themselves.

At the outset, a narrator explains the importance of the Leica camera for the people of Germany in the 1930s, when the society was at a crossroads after economic depression and the reformation of Hitler’s new government. Perched on a stand center stage is the camera in the spotlight, while projections of black and white photos scroll in the background, exemplifying the subjects taken by people using it. Some are of German people enjoying family events, as we note the narrator’s comment that in Germany, amateur photographers took up the activity as a national pastime and became “history’s most willing recorders.”

As the photos scroll showing stills of children and young adults giving the Hitler salute, the narrator suggests that “each frozen moment tells the world this is our shared history.” Her tone is ironic and the Hitler salute, as terrible as it is, physicalized by the bodies of children, indicates an alignment with Hitler’s politics, attitudes and way of life. Additional photos of children and adults enjoying outings, show Nazi flags; the narrator continues, the “apparent ordinariness of these images does not detract from their political relevance.” Indeed, she states, “On the contrary: asserting ordinariness in the face of the extraordinary is in itself, an immensely political act.”

In photographs and videos of Hitler’s marches by soldiers of the Third Reich (shown in the Nazi propagandist films of Leni Riefenstahl, etc.), we note Nazi militarization and might, which after a while are easily relegated to “the past.” Photographs throughout the play’s album note the Nazi flag, Hitler salute and SS uniform as a common fact of life lived at that time. Indeed, Hitler’s politics became the breath of life itself and all aspects of the German people’s existence and happiness were intertwined with Nazism, Hitler’s “great” leadership, his conquests, economic prosperity, and the ready identification with all of this by the average German. This was so until things went terribly sour and German war losses multiplied.

However, the Third Reich’s asserting ordinariness and commonality, when in fact it was anything but, is one of the concepts the archivists deal with throughout their journey to organize the photographs, categorize them and analyze what they are looking at in the photo album of the SS’ lives at Auschwitz.

The playwrights introduce us to the archivists in the second scene. It is then Rebecca Erbelding (Elizabeth Stahlmann), first reads the letter from the Lieutenant Colonel notifying the museum that an album with photographs from Auschwitz that he possesses might be of import. From that juncture on, we become engrossed in the archival journey as the researchers, experts and others delve into the album and attempt to understand it. Curiously, there are no photos of the victims and prisoners of Auschwitz.

As they take on the difficult task and uncover details through trial and error, eventually, researchers bring together the puzzle pieces which explain the photographs and identify the SS officials and the various workers up through the hierarchy, who helped Auschwitz seamlessly function. Clearly, Auschwitz was a huge endeavor that contained an industrial complex and barracks for laborers, housing for guards and administrators alike, and a killing machine and ersatz assembly line of death.

After pinpointing the owner of the album as Karl Höcker, who moved his way up to become the administrative assistant to the head of Auschwitz., the archivists (who also bring to life Karl Höcker and others via dramatization), gradually explore the lifestyle of those in the photographs. These include the SS guards, top brass, doctors, various secretaries (Helferinnen, who were in communications, etc., and held jobs at the camp), staff and others having meals, relaxing at a nearby resort and more daily activities.

None of the photos show the functions of Auschwitz, the prisoners, victims or crematoria. All is pleasant and reflective of the wonderful world that Hitler spoke about bringing to mankind after the “vermin” were removed. That the Helferinnen were photographed surprised a number of researchers who wondered if the young women knew about the gas chambers in the camp or smelled the acrid air of burning flesh in the crematoriums. After denials and relatives probing and finding innocence, what the women knew is later answered by one of the secretaries who was at Auschwitz. She was questioned after the war. Charlotte Schunzel stated she and the other women recorded how many were sent to hard labor and how many were sent to SB, “special treatment,” a euphemism for the gas chambers.

The archivists pin down the identity of the SS officers and high command in the photographs, one of whom was the notorious “Angel of Death,” Dr. Menegele. Another is the commandant who set up Auschwitz-Birkenau, Rudolph Höss. The researchers determine that the photos are like selfies that reveal the happy life of Karl Höcker (Scott Barrow), who would have been a “nobody” if he had not joined the Nazi party in 1937 and arrived at the camp in 1944, just in time to help “process” the thousands of Jewish Hungarians (350,000), who rode in trains three days, only to be murdered in gas chambers after they arrived.

Kaufman and Gronich seize our interest especially when actors take on historical personages, relatives of the SS, survivors, researchers, historians and others. in view of the audience, actors create Foley sound effects to usher in events and accompany Erbelding, Judy Cohen (Kathleen Chalfant), Charlotte Schunzel (Nemuna Ceesay), Tilman Taube (Jonathan Ravlv), Melita Maschmann (Erika Rose), Rainer Höss (Charlie Thurston), Peter Wirths (Grant James Varjas), and others as they uncover bits of information and puzzle together what is happening in each photograph.

The global attention the album receives (revealed by projections of headlines), brings new interest and revelations, some by grandchildren of the SS who are horrified to see uncovered aspects of their relatives they didn’t want to imagine. These aspects have been kept hidden from families out of shame and especially to avoid accountability. Perpetrators of murder and the accomplices to murder are still being located and held to account, even as recently as the last two years. Murderers and the complicit and culpable had a great need for covering up their crimes, as long as they were alive.

Another revelation comes from Holocaust survivor Lili Jacobs, who contacts archivists, as a result of the press reports. She had been holding on to an album she uncannily found of 193 photographs of the Hungarians arriving on the trains, all of whom were “processed” by the SS and high command in the photos. After she donates her album (it contains pictures of herself and family taken by the SS in the camp the day she arrived from Hungary), the researchers are able to solve the dates of the mystery of one photo which shows all the SS, high command and workers celebrating at Solahütte (a resort), where Karl Höcker occasionally rewarded the SS guards, workers, Helferinnen etc., when they did something special.

One example is given when guards prevented an escape by killing four prisoners. Administrator Höcker rewarded them for their “courage” by sending them to Solahütte for a few days.

Previously, the archivists couldn’t understand what and why the large group of camp officials, workers, drivers, Auschwitz staff, referred to by one archivist as the “Chorus of Criminals,” were photographed celebrating. However, through interviews with experts, and piecing together the facts, they divine why the entire group of Auschwitz Nazis standing and smiling, were enjoying the accordion music in one, fine, inclusive photograph, from the top brass in the front, to the lowly staff standing on a hill in the back.

With the evidence of the two albums together, archivists complete the full story of murderers and victims. The victims in Jacobs’ album were those who arrived in train transports from Hungary. The photographs included photographs of Lili and her family and her rabbi, right before they were separated into the lines for labor camp and gas chambers. In Höcker’s album, the administrator assembled and photographed the “Chorus of Criminals'” photograph for a vital reason. The murderers celebrating at Solahütte were congratulating themselves. They had successfully finished a job well done, the massive operation, processing Hungarians, dividing and selecting, so that 350,000 could be exterminated, among them Lili’s parents and two younger brothers.

Through their research, archivists discovered that Lili arrived one day after Höcker arrived at Auschwitz. He most probably received a career bump up to administer the massive “Hungarian Project.” In light of Lili’s discovery and sharing it with the archivists at the museum, she and they “get the full picture.” She sees the identity of the men who murdered her family. Finding the album of herself in the tie in with the album of the SS who ran the camp is an extraordinary sequence of events that is beyond coincidence. For her, the discovery is mystical and divinely spiritual.

Ironically, in Here There Are Blueberries, the victims that the Holocaust Memorial Museum has been so diligent about uplifting and respecting are not the only ones to be considered in studying and understanding the Holocaust. The innocent victims, indeed, were the extraordinary ones in Hitler’s politics that had infiltrated into the bones of the German people, but not the bones of the innocent ones ravaged by acts of the brutal tragedy delivered for the “good of the nation” in its lust for domination. The victims’ impossibly painful stories of survival or loss, escape, surrender, the trauma, and the horror, shock, astound and enrage.

That the ones who perpetrated murder and genocide were able to do it day in and day out as a matter of routine, a job to be done, exemplifies the normalization and internalization of a monstrous political attitude. That attitude that the SS, many Germans and surrounding cultures (i.e. Austria) adopted as right and true, a way of being, a way to live one’s life, which necessitated that others bleed and die for it as a general social good, is evidenced throughout Hocker’s album of photographs of the SS’s smiling faces as they perform daily activities.

It is this above all that Kaufman and Gronich bring to the table and highlight like no other work, with the exception of Martin Amis’ novel Zone of Interest, about the life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, which was recently made into a film, directed by Jonathan Glazer. However, unlike Zone of Interest, Kaufman and Gronich don’t include responsive photos to the crematoria. All photos of camp function and purpose are missing. Only in Lili Jacobs’ companion album do we note the horror of the transports and the photos of her rabbi, her parents and siblings who died.

The photos of those accountable for all of the activities at Auschwitz, their reason for being there-to kill, oppress, subjugate and promote the war effort-is implicit. Their very images in the photographs stink with the noisome odor of the gas chambers. The absence of the victims and any evidence of the killing machine, a final realization of the archivists who investigate the album, if anything, incriminates all of the SS officers even more in their guilt. If they were innocent and in the right, why did Höcker need to edit out the buildings of the killing machine, the prisoners and torturing that happened in the labor complex? Why did he need to present his album of “happy days are here again?” when obviously the smoke of the burning had to be hidden?

In the archivists’ explorations they learned the backgrounds of the SS running the camp were ordinary-former clerks, bank tellers, confectioners, teenage girls. We are prompted to ask what separates these murderers and accomplices to murder from the rest of us? Stating the Nazis were monsters allows us the luxury to say “we are not like them.” It dupes us to think we would never be caught up as these were, convinced in the rightness of their actions. This is a dangerous attitude. Indeed, playwright Kaufman reflects the overriding theme of Here There Are Blueberries when he states that “the Nazis were not monsters-they were normal people who did monstrous things.”

How are political cults convinced of their rightness convinced to murder for the right? How did the January 6th insurrection fomented by a sore loser with revenge on his mind to punish his VP because he didn’t do what “was right” happen? Are there any elements that might be compared? This amazing play is filled with parallels to our time, as it raises profound questions about our humanity. For that reason, as well as the fine dialogue and overall presentation and ensemble work, one should see this play.

Here There Are Blueberries runs 90 minutes with no intermission at NYTW on 4th St. between 2nd and the Bowery. Don’t miss it.

‘The Half-God of Rainfall’ at NYTW, Review

Inua Ellam’s epic poem The Half-God of Rainfall, has been brought to life with theatrical grist at New York Theater Workshop. Currently running until 20th August, the reconfiguration of Greek, Yoruba archetypes and myths are merged against a modern backdrop of an Olympic basketball champion born of mixed raced parents, a simple Nigerian woman Modúpé (Jennifer Mogbock) and the Greek god of thunder Zeus (Michael Laurence).

Their fantastic progeny is the half-god Demi (Mister Fitzgerald). It is his exploits and the overthrowing of the patriarchy which the actors narrate, illustrate, move through and reimagine during the 90 minute spectacle of sight, sound and movement that is strongest and most exhilarating during the last 15 minutes of production.

Ellam’s poem is ambitious as is director Taibi Magar’s vision for The Half-God of Rainfall’s breadth and scope. Interestingly, the very nature of the foundational myths of the Western world vs. African folklore and tradition collide like tectonic plates during an earthquake. Thus, when god of thunder Sango (Jason Bowen) loses the competitive race against Michael Laurence’s Zeus and must yield his finest prize Jennifer Mogbock’s Modúpé, Zeus’ rape and the birth of their son Demi is symbolic of the traditions of war between conquerors and their conquered. Rape was and still is a subduing weapon of war, legitimized as acceptable spoils of conquest.

Without a father, raised by his mother, Demi is typically disadvantaged and rejected by his peers, despite his apparent supernatural gifts as a demigod. Eventually, as a Marvelesque hero of stature and statuesque build, Demi receives the fullness of his powers and becomes a basketball great on the Golden State Warriors team. There, he learns about other demigods whose talents suppressed in their natural lives shine in competition as his do.

However, his greatness eventually becomes known to his father Zeus, whose machismo and fiercely tyrannical spirit compels him to confront his son. Will Demi be able to schmooze his father and encourage him to receive his son with paternalistic pride? Or will another result occur where he overthrows the oppressor culture and vaunts his mother’s African traditions? Which identity will Demi embrace and will he be able to meld the two and tease out the best in both mythic and cultural traditions? These themes and conundrums are answered by the conclusion.

As the poem/dramatization progresses, the other deities contribute to chronicling the high points of Demi’s story. These gods include Zeus’ wife Hera (Kelley Curran), Elegba (Lizan Mitchell), and Osún (Patrice Johnson Chevannes). Peppered throughout with philosophical wisdom and historical reference points of Greek and Western colonial oppression, the dramatized poem emphasizes that the conquerors treat their subjects with opprobrium, alienation and objectification. Additionally, the deities reveal that like rape, cultural assimilation is a weapon of war. Diluting the cultural artifacts, language and human traits of a race are the ultimate form of conquest and annihilation.

Ellams’s poetry is both rhythmic and expositional. The actors hone a fine sense of the poetic beats in each segment bringing the meaning into focus. Their storytelling is elucidated by Riccardo Hernandez’ scenic design, Stacey Derosier’s lighting design, Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design and Tal Yarden’s projection design. The actors don Linda Cho’s costumes as a part of the action comfortably aligning themselves with their various roles as they move in and out of their characters seamlessly.

Beatrice Capote’s Orisha movement and choreography flows and indeed could have been incorporated much more, especially during the characters’ presentational narratives. Likewise, Orlando Pabotoy’s movement direction might have been integrated more to enhance the spoken-word which the actors direct to the audience as they tell Demi’s story.

Striking are the immersive elements, of creative design, for example the use of shimmering blue cloth which the actors use to effect undulating water. The beautiful projections suggest the majesty of the cosmos the gods inhabit. Other multi-hued projections reflect both the ethereal and the manifest world of the earth which Demi attempts to inhabit and conquer in his own right. Likewise, the falling rain is a palpable effect to ground us in this realistic yet stylized piece where the director elicits how phantasms are present in the reality we see, and think we know, but do not.

Overall, the actors effect emotional intensity especially at the conclusion. Because there are fewer scenes of interaction between the characters, one wonders if the first half of the production might have benefited with more movement and character dynamic rather than the actors’ direct addresses to the audience.

However, Magar brings the events to a satisfying conclusion as Mogbock’s Modúpé vindicates her own humanity and the cultural, historic, African traditions bringing release and redemption. The finish is as startling as the heartfelt events that prompt Mogbock’s Modúpé’s final, relentless actions.

The actors and creative team have generated a unique experience so that Ellams’ epic narrative leaps off the page and into one’s imagination with their fine stagecraft. For tickets and times go to the NYTW website https://www.nytw.org/show/the-half-god-of-rainfall/

‘How to Defend Yourself’ at New York Theatre Workshop

In this decade of sexual extremes on a continuum from paranoia, political correctness, libertine licentiousness, the billion dollar pornography industry and casual permissiveness, one in four women is violated, sexually assaulted or physically/emotionally abused. As a strategic defense #metoo has been appropriately employed culturally, but it also has been wrongfully magnified as a double-edged sword of vengeance. In Liliana Padilla’s play How to Defend Yourself, currently at New York Theatre Workshop, following a successful 2020 run at Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theatre, Padilla confronts important issues about personal safety both emotional and physical. Incisively co-directed by the exceptional Rachel Chavkin, Liliana Padilla and Steph Paul, the hybrid comedy drama explores consent and the litigated definitions of rape and harassment, which shift based upon geographical location, accuser and victim.

With the setting as a torpid and tumultuous college campus, when individuals are beginning to define their goals, dreams and intentions, sexuality and choices remain fluid. A decision to be with someone can lead to devastation, especially around stimulants, alcohol and drugs at a testosterone-fueled frat party, where young women are pressured to compromise themselves. At the top of the play we are introduced to women in a self-defense class started by college junior Brandi (Talia Ryder). The confident, black belt, with social media videos of herself disarming a bully with a gun, is a self-appointed, self-defense instructor. Brandi decides to teach students the ways to protect themselves, after sorority sister Susannah is raped and hospitalized. The assault happened at a frat party.

Much of the enjoyment of Padilla’s play is becoming acquainted with the buoyant women and two young men in the class. They reveal their humorous attitudes as they attempt to navigate a culture whose roiling currents are being defined from moment to moment, often dislocating both men and women. All genders of that age group may be easily overcome by intimate circumstances, which they assume they have control over but don’t.

Brandi, whose self-assurance, determination to do good and organized, talented, physical skills, not only looks dancer-fit, but is also lovely. Admired and accepted by her peers, she is a member of a hot sorority and has the cache to hold self-defense sessions. These attract a few neophytes who are there to learn self-defense. Some are there for other reasons.

Brandi runs her sessions circumspectly with precision. She expects her peers to evolve toward her confidence level, so they understand that “anything can be used as a weapon,” and primarily, “their own bodies are weapons.” Kara (Sarah Marie Rodriguez), joins her BFF for moral support and fun, but she lacks Brandi’s skill set. Kara assists Brandi with chatter and chalkboard drawings in the college gym space (finely designed by You-Shin Chen), where Brandi holds classes.

Two students, who drift in anxious to get started, arrive before Brandi. We learn that freshman Diana is obsessed about defending herself against guns. Her BFF Mojdeh follows fast in her orbit. Humorous and sociable Diana ((Gabriela Ortega at the top of her game), and Mojdeh (Ariana Mahallati), are primarily there to get closer to Brandi, who is a Zeta Chi, the sorority they would like to rush. It escapes them that the group think atmosphere of sororities and fraternities are precisely the communities that can be toxic and abusive. However, Mojdeh craves being identified as “cool.” She seeks the hot, popular individuals to ride their coattails and achieve acceptance. For her, this is the fastest way to self-love. On the other hand, Diana appears to be self-content, and is humorous in how she fetishizes guns to the point where by the the end of the play, she indulges her passion.

The last young woman to join Brandi’s sessions is Nikki (Amaya Braganza). Her entrance provokes laughter because she appears super shy, hesitant and awkward. Throughout, she is mysterious and reticent, until the conversation opens up, and she admits she gave a “blow job” to a guy in a gasoline station. When Brandi and Kara attempt to kindly excuse her humiliating, crass behavior as a mistake, she states that she was fine with it, and it was her idea. Whether she is lying or fronting is difficult to surmise. Hiding behind “it’s OK,” is oftentimes the default response because it is too messy to get into, who is responsible, who is to blame and what forced sex means.

Kara indirectly insults Nikki by stating that she also has made such “mistakes.” Nikki is nonplussed, revealing the differences in attitudes between the two young women. Clearly, the circumstances around sexual behavior are extremely complex and not easily understood. Subsequently, Padilla’s characters veer off topic into personal discussions about what forms of touching make them uncomfortable, and what physical boundaries work.

The play reveals that the idea of self-defense encompasses more than just a physical way of being. Young men and women are at sea with regard to “growing up” with a sexual identity that is forced upon them by the culture and their friends. Oftentimes, as Jayson Lee’s Eggo suggests, they are clueless about what is the right or wrong way to conduct themselves, have relationships and fall in love. Sexuality isn’t necessarily the main ingredient that holds people together.

To add substance to the mix, Padilla includes the male perspective, having Brandi invite two fraternity brothers, Andy (Sebastian Delascasas) and Eggo (Jayson Lee). They are “down” with #metoo and are supportive of Susannah during her recuperation and rehabilitation from the stress of her assault. To add to the complexity, their fraternity brother has been criminally charged which has put the entire fraternity on “high alert.” To distinguish themselves from the “sexual abuser types” roaming their campus, Andy and Eggo hysterically ply their sanctimonious “we support women” front, the moment they enter the room and introduce themselves. Years in prison hovers over the head of their fraternity brother, and they are “running scared” that any of their behaviors might be interpreted as predatory. Their loud, moralistic approach toward women is “over-the-top,” and we expect they will marching in the next women’s protest to encourage female empowerment.

Padilla’s themes are not lost on us. Sexualized images and behaviors, part of the landscape of American culture in the entertainment industry and fashion industry, were shattered by #metoo. The nascent revolution that sprang up after the Harvey Weinstein debacle shuttered a billion dollar company and gave pseudo power to women for a time, only in the parts of the country which are not Republican and are “woke.” In other areas, the men act as they please, and the women go along with it, especially if they are proving they are not “socialist lefties.”

In the play, the characters are diverse: three persons of color, a Mexican-American, an Iranian-American and two whites. They are stuck with having to deal with “woke” culture, especially after the campus assault. Importantly, there is a discussion in the middle of the play about what consent means. Additionally, the question about having to always check with a partner about boundaries is raised. Kara blows up the discussion with her suggestion that there is nothing wrong with wanting S and M sex. To avoid the confusing topic, which adds another complex component about individual sexual behavior, Brandi calls her out for being inappropriate.

Clearly, Kara has issues with alcohol and wanting to be hurt. This hints at her subterranean troubles that are never revealed. We note such problems, when she doesn’t join in the physical sessions because she got “wasted” the previous evening. On the other hand, she isn’t embarrassed about sharing her enjoyment of rough sex. Apparently, she also enjoys the shock value of telling others about herself, though it is counterproductive to her BFF’s purpose in holding the class. From this turning point onward, the situations in the self-defense class run off the rails.

The most interesting segments of the production are the self-defense moves that Brandi teaches (well choreographed by Steph Paul, movement director), and the physical fight routines they accomplish together (at the guidance of Rocio Mendez). Late in the play there is a fight that breaks out between Diana and Kara that is well staged. The fight exemplifies that ego, charm and pride are competitive forces that stir up internal problems within the young women. These spill out in violence. Between Diana and Kara, there exists an intuitive impulse to dislike each other. That disgust eventually dissipates after Diana smashes the provocative Kara in the face, ironically proving that Kara does seek physical abuse.

The staging for the defense practice scenes works seamlessly and is powerful and exciting to watch. The movements are pitched to music, which pumps up the characters and reveals they are gaining confidence about themselves. Additionally, when Brandi suggests they pair off to practice techniques, for example, how to break an attacker’s wrist grip, the results are simultaneously wrought and the overlapping dialogue and action make for fascinating comparisons.

There are surprising turns throughout. Diana and Mojdeh discover things about each other that set their relationship on a different path so that they can’t be close anymore. Kara and Brandi have a disagreement about Susannah, and Andy reveals a secret to Eggo that he has been harboring since the attack on Susannah. This upsets them and dislocates their sense of well being even more. When Andy asks what he should do, Eggo is at a loss. We understand there are no easy answers with regard to human sexuality and situations worsen as a result of “not knowing what to do.” Finally, after a number of sessions where Brandi’s “students” have progressed, and she feels she has made inroads into helping them feel safer, Nikki upends her assumptions and disturbs everyone with an event that she describes.

The thematic conclusion moves through flashbacks in the characters’ stages of adolescence. The directors show the individuals at three parties during their teen years, which move backward in time to a birthday party when they were in elementary school. The parties reveal the wildness from the drinking and sexual exploration when they were in high school. In the last party they end up in the sweet innocence of their elementary school days. The contrast of how they seek sexual experience that emerged from a time of innocence is stark and mind blowing.

For the rapid set changes You-Shin Chen, Stacey Derosier lighting designer, Izumi Inaba costume design and Mikhail Fiksel’s sound design create a frenetic party atmosphere. And the lovely tableau at the end reveals that the progression of their identities has sprung from love, security, family and well being. One might think that these create an assured line of defense to thwart any attack that might ever happen.

However, Padillia posits that security is never guaranteed. Though we may use our bodies as weapons, or learn self-defense, random and not so random acts of violence happen in a culture that uplifts violence. Diana feels forced to arm herself with a licensed gun as an answer to that violence. Tragically, the subtext of her statement about guns plays out daily in our society, revealing the play’s devastating currency. Its themes about our physical and psychic vulnerability in an arbitrary and violent world resonate with power.

Co-directors Rachel Chavkin, Liliana Padilla & Steph Paul are responsible for the strengths of the production, especially its staging and thematic depth. Their vision about the questions the play raises leaves us with even more questions and no clear answers. The actors are uniformly excellent and the physicality and staging of the various defense sessions make one want to get up and join the cast to try out all the moves.

How to Defend Yourself is a humorous, weighty production, whose trenchant themes give us pause, thanks to the vision and talent of its creatives. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.nytw.org/show/how-to-defend-yourself/tickets/

‘runboyrun’ and ‘In Old Age’ Two Magnificent Works by Mfoniso Udofia

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes in runboyrun and In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

What is the impact of experiencing a genocidal civil war when one’s ancestry, bloodline and religion are used as targeted excuses for extermination? If one survives, is it possible to overcome the wartime horrors one experienced? Or is the sufferer doomed to circularly repeat the emotional ravages of past events that erupt from the unconscious and imprison the captive forever in misery? How is such a cycle broken to begin a process of healing?

In runboyrun, Mfoniso Udofia, first-generation Nigerian-Amerian playwright, through poetic flashback and mysterious revelation, with parallel action fusing the past with the present, explores these questions. Majestically, in her examination of principal characters Disciple Ufot (the superb Chiké Johnson), and his long-suffering wife Abasiama Ufot (the equally superb Patrice Johnson Chevannes), we witness how Disciple overcomes decades of suffering with the help of Abasiama during a night which is a turning point toward hope and redemption.

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, Karl Green, Adrianna K. Mitchell in runboyrun and In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

A bit of backstory is warranted. In 2017 New York Theatre Workshop presented two of Mfoniso Udofia’s plays in repertory (Sojourners, Her Portmanteau). runboyrun and In Old Age are two of Mfonsio Udofia’s offerings which are plays in The Ufot Cycle, a series of nine plays in total which chronicles four generations of a family of stalwart women and men of Nigerian descent. Though the plays currently presented at NYTW are conjoined to elucidate similar themes, they do not run in sequence. Nevertheless, both plays spotlight Mfonsio Udofia as a unique female voice of the African diaspora in the United States. Both represent the particularity of her exceptional work from a maverick’s perspective.

The first play directed by Loretta Greco begins with a flashback of a sister and brother. The setting is January, 1968 Biafra, the southern part of Nigeria that attempted to gain independence from Nigeria during the three year Biafran Civil War. During a lull in the shelling by the government in a hideout in the bush, the sister comforts her brother with a metaphorical story about the foundation of humanity and life. Then she encourages him to run as a game. However, it is the one activity that will save their lives as they escape the Nigerian soldiers at every turn, until they reach a safe place in a compound with their mother and brother.

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, Karl Green, Adrianna K. Mitchell in runboyrun and In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

This setting alternates to the present January, 2012, where we are introduced to the Ufots, transplanted Nigerians who immigrated to the United States, became citizens and eventually settled in the ramshackle interior of their colonial house in Massachusetts. However, from the moment Johnson’s Disciple enters their cold, dank home and with bellicosity relates to Chevannes’ Abasiama, we understand that their estrangement is acute. For her part Abasiama, who lies on the couch in the center of the living room wrapped up in layers of clothing with blankets and sheets thrown over her head, disengages from his behaviors, attempting to stay away from his weird, oppressive antics.

Disciple attempts to control her every move, berates and blames her for the bad spirits in the house. However, it becomes obvious that it is he who suffers derangement. He is fixated on the perception that everything outside him and especially his wife are the source of his bad luck and the wickedness that plagues him and threatens to upend his life and his writing. In what we learn has become a ritualistic practice, Disciple uses a thin stick to circumscribe areas as safe to prevent evil spirits from disarranging and unsettling his peace. Abasiama, used to this behavior, plays Christian music; Christianity was a part of their Igbo ancestry. However, after Disciple’s exorcism, when he attempts to begin work on a new book, the past erupts. Once more the playwright creates flashbacks which establish and explain Disciple’s instability and borderline insanity.

The full cast of runboyrun, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco (Joan Marcus)

Udofia’s structure interlacing the past with the present is particularly strengthened by Andrew Boyce’s scenic design which threads the action, symbols and themes. The house is divided in a cross section symbolizing the division in Disciple’s and Abasiama’s relationship and marriage so we see how both conduct their lives in separate parts of the house: Abasiama upstairs, Disciple in the basement. They do not communicate, nor are they intimate with each other’s thoughts and feelings, sharing little if anything of their histories, a tragedy which has led to the disintegration of their marriage. Their lives are separately lived; they buy food separately, use different refrigerators. Disciple cooks for himself and they take their meals separately because he believes she may poison him.

The separation extends even to the different churches they attend and Disciple’s cruel treatment of Abasiama, which she sustains because to take a stand against it would rain down more abuse. Disciple begrudges Abasiama warmth for the upper floors which have insufficient heat to brace up against the cold Worcester, Massachusetts winter. This behavior of keeping the upper floors cold reflects Disciple’s abusiveness and penuriousness, not only with finances but with emotional intimacy and love.

Chiké Johnson, Patrice Johnson Chevannes in ‘runboyrun’ and ‘In Old Age,’ written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Loretta Greco, Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

The division/cross section symbolizes a number of elements which define the characters so acutely portrayed by Johnson and Chevannes with maximum authenticity. It represents the compartmentalization of Abasiama’s and Disciple’s minds, especially Disciple’s as it relates to his unconscious memories which he’s suppressed, and on this night erupt with great ferocity. For Abasiama, she compartmentalizes her rage and anger against Disciple; to express the emotions will result in violence so she must be stoic. The events that play out from the past take place in the “basement” area. Events move upstairs when Abasiama extends grace to Disciple and he relives the flashback that has shaken his soul and increasingly knocked on his heart to be released as he has aged. If he does not, surely he will damage and destroy everything he has, most importantly his relationship with Abasiama.

It is in the “basement” of his being on this particular night that Disciple confronts the spirits that have haunted him for decades. By the play’s conclusion he revisits the blood soaked memories of his childhood during the horrors of the Biafran War. The spirits rise and their energy drives him to the brink of irrationality, which he takes out on Abasiama, who finally proclaims “enough,” and tells him she wants a divorce. In shock he returns downstairs and she hears him raving against the energies that roil him (his unconscious terror and guilt).

Adrianna Mitchell, Karl Green, ‘runboyrun,’ written by Mfoniso Udofia (Joan Marcus)

Mfoniso Udofia expertly weaves in concurrent flashbacks which reveal seminal events that shattered Disciple’s consciousness and emotionally freeze him in time. We learn why he is psychotic in recreated scenes of his family: sister (Adrianna Mitchell), mother (Zenzi Williams), Benjamin (Adesola Osakalumi). Karl Green portrays Disciple as a boy. And on Abasiama’s encouragement and love, he finally reaches the core event to expurgate it and grieve, thus beginning the healing process.

Chiké Johnson is acutely, sensitively invested in his portrayal of Disciple. Patrice Johnson Chevannes as Abasiama is expert and uplifting at the conclusion of runboyrun. And in the segue to the next play, we see her transformation into a withered, dried up old woman living with the rage and fury bestowed upon her by Disciple who has died by the opening of In Old Age.

Ron Canada, Patrice Johnson Chevannes in In Old Age, directed by Awoye Timpo, written by Mfoniso Udofia (Joan Marcus)

It is Abasiama’s fury that has carried over from her time with Disciple that Mfoniso Udofia examines in the play In Old Age. The stoicism we see in runboyrun blossoms into rage against herself for “putting up with” Disciple and not leaving him. Whether such anger manifests when we age, so that we have no tolerance for ourselves and are grumpy and angry with others is an interesting question that Mfoniso Udofia posits. Yet, it is in Abasiama’s interactions with Azell Abernathy the workman (Ron Canada), that the emotional abuse she never discussed or confronted Disciple about is now coming to call. And likewise, the tragic alcoholic-fueled abuse that centered around Abernathy’s marriage, that Abasiama intuits harmed his marriage, becomes a focal point of their interactions.

Abernathy and Abasiama clash and their expressed annoyances with each other are sometimes humorous. However, because they are both Christians, they attempt to bear up with one another. Indeed, Abernathy is much more determined to do so than initially Abasiama seems to want to. How Mfoniso Udofia brings these two together to establish the beginnings of a loving relationship is a lesson in grace and the spiritual need for forgiveness and emotional healing.

Ron Canada, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, ‘In Old Age,’ written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

The plot development of In Old Age is simple. Azell Abernathy must persuade Abasiama to allow him to repair her house, the same house that she lived in with Disciple. However, the house is in more than need of repair. Abasiama hears what she believes is Disciple ranging and banging around in the basement. Just like in runboyrun when Disciple projected his terror and hurt onto Abasiama, now Abasiama projects her rage and anger onto the house and in magical realism fashion, it manifests in banging and noise.

One of the problems is that Abasiama subverted her own healing and empowerment to help Disciple redeem himself. Now she regrets her sacrifice and unselfishness. As a result, when Abasiama is forced to deal with Azell Abernathy (Ron Canada in a highly nuanced, sensitive, clarion performance), whom her daughters have paid to repair the house, the rage has so swelled inside of her she drips bile. Toward Abernathy, she is provocative and she riles him to the point where he nearly becomes abusive. However, he has learned. He leaves, goes outside and prays for her.

Ron Canada, Patrice Johnson Chevannes, In Old Age, written by Mfoniso Udofia, directed by Awoye Timpo (Joan Marcus)

His prayers work with power and change comes with revelation. Abasiama realizes she can no longer carry around past hurts and regrets. To expurgate them, she cleans out the “basement” (symbolic of her own soul and psyche), of all of the artifacts that Disciple kept there. As she throws them out, she frees herself realizing she is responsible for her own happiness and cannot blame her misery on Disciple. Cleansed from a night of dealing with her own regrets about her life, Abasiama is ready to face a new day. In a great, symbolic gesture, Abernathy washes her feet as Christ did with his disciples, showing he forgives her and forgives himself. It is an act of sublime strength. She receives his good will, Christian love and faith. She removes her shackles represented by her headdress and shows Abernathy her true self. She is beautiful. In their old age they have found love after confessing their faults to each other to be healed.

In Old Age is a hopeful, redemptive encomium to our ability to grow and regenerate our souls if we face ourselves. Directed by Awoye Timpo, In Old Age is just lovely and the complex performances by Canada and Chevannes are sterling, poignant and uplifting. Kudos to Andrew Boyce (scenic design), Karen Perry (costume design), Oona Curley (lighting design).

These are productions you do not want to miss for the profound beauty of Mfoniso Udofia’s work and the great ensemble acting. The tension in runboyrun is truly striking. runboyrun and In Old Age are at NYTW on 4th Street between 2nd and the Bowery. The production runs with one intermission. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

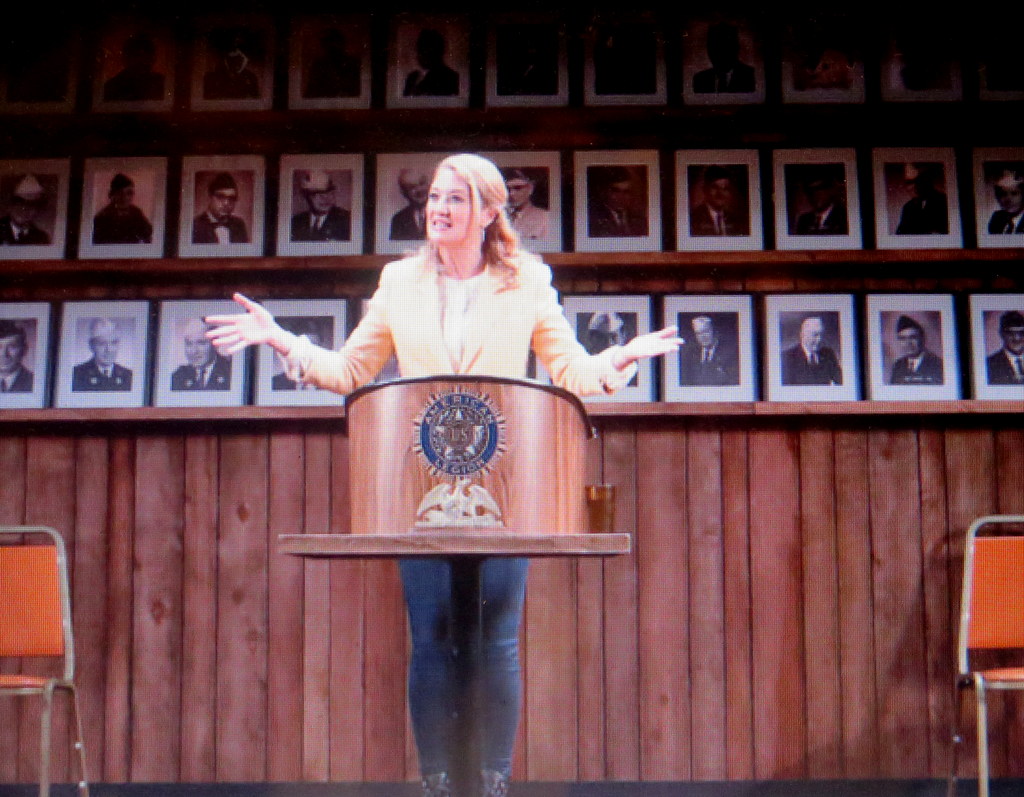

Theater Review (NYC): ‘What The Constitution Means to Me’ Starring Heidi Schreck

(L to R): Rosdely Ciprain, Heidi Schreck-playwright, Thursday Williams, Mike Iveson, ‘What The Constitution Means to Me,’ NYTW, (Joan Marcus)

Depending upon how you view the months since the 2016 election, playwright, actress Heidi Schreck’s timely What the Constitution Means to Me casts a long shadow and provides trenchant perspectives. Of course one may view it simply as a pleasurable, informative romp through a document most remain clueless about. Or perhaps one may identify that her humorous, vibrant writing more profoundly remains a siren call to “get woke!”

Indeed, the production staged and set in an American Legion Hall, directed by Oliver Butler, stars award winning actress and writer Heidi Schreck. And it took years in the making. With assistance by fellow actor Mike Iveson and debater Rosdely Ciprain, the result sparkles. Schreck’s crisp, sharp, ironic writing encapsulates American themes and pivotal, historical moments that changed our laws. Abundantly, these perplex. For they concern the constitution’s long-range evolution toward greatness. But Schreck also includes how the people have stretched the document over the chasm of far reaching human miseries. At any time it may break, and our society plummet into the abyss. Her work and its cattle-prod intent remain a fascinating, thought-provoking must-see.

Indeed, humorous and enthusiastic throughout, Schreck’s “light-hearted” approach belies the seriousness of the subject in today’s light/dark atmospheres. For she presents profound and disquieting principles and facts about our lives that we cannot dismiss. And she accomplishes what the news media at times does not. She presents with succinct, factual details and logical arguments that clarify. Importantly, she makes one think beyond memes and spurious arguments, troll epithets, and misinterpretations!

Rosdely Ciprain, Heidi Schreck, Mike Iveson, Clubbed Thumb in partnership with True Love Productions, ‘What The Constitution Means to Me,’ (Joan Marcus)

This alone remains worth the price of the ticket. In fact her production should be opened to area schools. Sitting just 10 minutes into the first half of the performance solidifies why. With a facile, funny, and vitally spontaneously delivery, Schreck becomes our vibrant teacher and historian. Notably, she proves the past abides in the present through her debates about the amendments. These concern those (9th, 4th), not typically familiar. Nevertheless, she proves why we should know them as crucial to our rights and well being.

During the production, Schreck reveals her personal veneration of our country’s democratic principles particularly outlined in the laws written after the Civil War. The quotes from distinguished justices and presidents alike illuminate. Assuredly, most amendments guarantee equity for every citizen and the rights of due process for all. And she notes the pitfalls where such principles and laws wobbled and continue to shake. Subtly, she infers that we must continually apprise ourselves of our constitution’s ever flexible nature.

Heidi Schreck, actress, playwright, ‘What The Constitution Means to Me,’ directed by Oliver Butler, NYTW (Joan Marcus)

Evolution and devolution include the same letters save one. In other words we are a letter away from the collapse of the bedrock laws of equity. If pernicious, power-usurping partisans undo just applications for the great majority to benefit the proportionately few wealthy, contentment, and prosperity wanes for most citizens. Exemplified, though not mentioned in Schreck’s work would be Citizens United which favors corporate donors giving multi-millions to politicians’ PACS thereby owning them.

Additionally, her discussion relating the constitution’s impact on women in her own family acknowledges strides. But it also portends fissures and potential earthquakes setting “women’s rights” back decades. This discussion Schreck attends to in the second segment of her production

Winningly, in the first half Schreck recalls her teenage years and how she employed her reading, writing and research skills to earn needed college scholarship money. As a teenager she competed in debates for various prizes from the American Legion. Indeed, these competitions challenged her thinking and debate skills. Of course her presentation centered around “what the constitution meant to her” at that age. Thus, she uses this presentation format which she delivers to white military legionnaires (we, her audience, become them), at the American Legion Hall in the state of Washington. And returning to her teenage self, she argues the constitution’s relevance to her, evoking these debates. In the fast forward to now, we compare notes and assess our progress in the current times.

This clever vehicle allows Schreck and Mike Iveson (as a Legionnaire and himself), to set up her detailed and fascinating account of women in her family and how the constitution might have and then did impact them. As she discusses the lies promulgated to bring women to settle Washington state (one woman for every nine men), she enumerates the suicides and death rates of wives at the hands of their husbands. For example, her great, great-grandmother, a mail-order bride, ended up in an asylum and died of melancholia in her thirties. Schreck ruminates about the possible back story of what happened to her. Dismissively, we may think, “times have changed.”

Heidi Schreck, actress, playwright, ‘What The Constitution Means to Me,’ directed by Oliver Butler, NYTW (Joan Marcus)

Then, she reveals today’s statistics. One in three women will be abused by male partners. One in four women are raped by men. And half of women killed die at the hands of their partners. However, women, no longer chattel (property), may seek justice. At one point in our history husbands could kill their wives with impunity. Yet, with lawsuits against Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Harvey Weinstein, and others, the #MeToo movement is a vital necessity. But will it negatively impact the constitution with the recent justice appointment?

In the third segment Schreck goes head-to-head with a student debater about whether we should keep or abolish the current constitution and create a new one. The evening I saw the production, Rosdely Ciprain revealed her feisty, funny debating chops and bested Schreck. However, Schreck’s spot-on argument about creating a positive rights constitution like those found in many European countries rang with sound truth.

What are negative vs. positive rights? Our negative rights constitution insures what the government cannot do to its citizens. On the other hand a positive rights constitution indicates what the government must provide: safety, security, healthcare, a living wage. After WWII FDR intended to institute a Second Bill of Rights which would have shifted the direction of our rights to positive ones. Of course, this became anathema to conservative corporates. And they held sway over our government and still do today.

Ours is a negative rights constitution. Hence, the government does not guarantee affordable healthcare, a decent living wage, human rights over corporate rights, mandates limiting excessive CEO pay, a proportionate equitable tax structure, etc. And it may rescind a “woman’s right to choose” what she might do with her own body.” Certainly, our congress has yet to pass an Equal Rights Amendment.

Preamble to the Constitution, Heidi Schreck, ‘What The Constitution Means to Me,’ NYTW, directed by Oliver Butler, (photo courtesy of the site)

Throughout, this superb production keeps one enthralled and laughing. But Schreck’s points run far and wide as she encourages our active participation in civics to understand our current historical reckoning. Thematically, she infers much. I divine from her work that like watchful sentinels, we must support the ACLU and other advocacy groups. And with them we must hold accountable our politicians to prevent thinning the constitutional threads so that they never break. Indeed, we must prevent the political think tanks and lobbyists who control our legislators from overriding through the courts the will of the majority of U.S. taxpayers/citizens. In the current tide of the Supreme Court Justice Kavanaugh times, this “must” appears more problematic than ever.

However, Schreck evokes a hopeful image her mother, a feminist, suggested to uplift her. First, picture a woman walking along a beach with a dog which darts back and forth, in the tide and waves. The dog races forward then races behind her and backtracks from whence it came. Then it moves forward, then backward. However, the woman walks forward, forward, steadily, slowly, undeterred, forward. This metaphor encourages us to hope. Not only to hope for women, but to hope for men, and LBGT communities who support equitable, positive rights for all born in this nation. And along with hope must come the energy to debate and persuade with reason and logic how undergirding the vulnerable and weak strengthens the strong.

The production currently at New York Theatre Workshop (83 E 4th Street) until 28 October, runs with no intermission. With scenic design by Rachel Hauck, costume design by Michael Krass, lighting design by Jen Schriever, and sound design by Sinan Zafar, this humorous masterwork should be extended. Hopefully, it will attend at another venue at some point in the near future. For tickets and times go to nytw.org.