Blog Archives

Susan Stroman Interviewed by Sharon Washington, a LPTW Event

On Friday, November 17, the League of Professional Theatre Women held an interview of an icon in the theater, Susan Stroman. The event was part of The Oral History Project which is held at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. The venue was the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center/Bruno Walter Auditorium.

Currently produced for the League by producer and director Ludovica Villar-Hauser, The Oral History Project was founded and produced for 26 years by the late Betty L. Corwin. The interview of Susan Stroman by friend and colleague Sharon Washington was video taped and will be archived in the collections of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

How Sharon Washington and Susan Stroman met

After comments by President Ludovica Villar-Hauser, and introductions, Sharon Washington (check out her credits and work on https://iamsharonwashington.com/), began by sharing the story of how she came to first meet Susan Stroman in 2009. At the time, Washington’s agent suggested she audition for a part in a musical, though Washington was a dramatic actress. When Washington posed that she hadn’t been in any musicals, her agent reassured her that in this one, she wouldn’t have to sing, dance or speak. Ironically, Washington questioned why she would even consider such a part. However, her agent countered that it would be directed by Susan Stroman.

Thus, Washington and Stroman collaborated on the 12 times Tony nominated Scottsboro Boys. The musical went on to win the Evening Standard Award for Best Musical in the UK. Though the production didn’t win any Tonys, Washington emphasized that then and now, Stroman’s process is exhilarating.

Specifically, Stroman creates a safe room that is caring. Washington and the other cast members felt so comfortable that they could work freely. Washington pointed out during the interview that Stroman imbues a quality of trust to be a creative collaborator. In her safe space one can try things out and make suggestions. This artistry of bringing out the best in the cast and creative team has brought Stroman accolades and forever friends. Sharon Washington is one of them.

Susan Stroman is a theater Icon

Susan Stroman (Director/Choreographer), is a five-time Tony Award-winning director and choreographer. She has won Olivier, Drama Desk, Outer Critics Circle, Lucille Lortel Awards. Also, for her choreography, she has won a record number (six) of Astaire Awards. Recently, she directed and choreographed the new musical New York, New York, which was nominated for nine Tony Awards and which won Best Scenic Design for a Musical (Beowulf Boritt). The music was by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb and Lin Manuel Miranda, and a book by David Thompson and friend Sharon Washington.

In other recent work, she directed the hysterical, LOL new play POTUS: Or, Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive. And this season in London’s West End, she directed and choreographed the revival of Crazy for You at the Gillian Lynne Theatre.

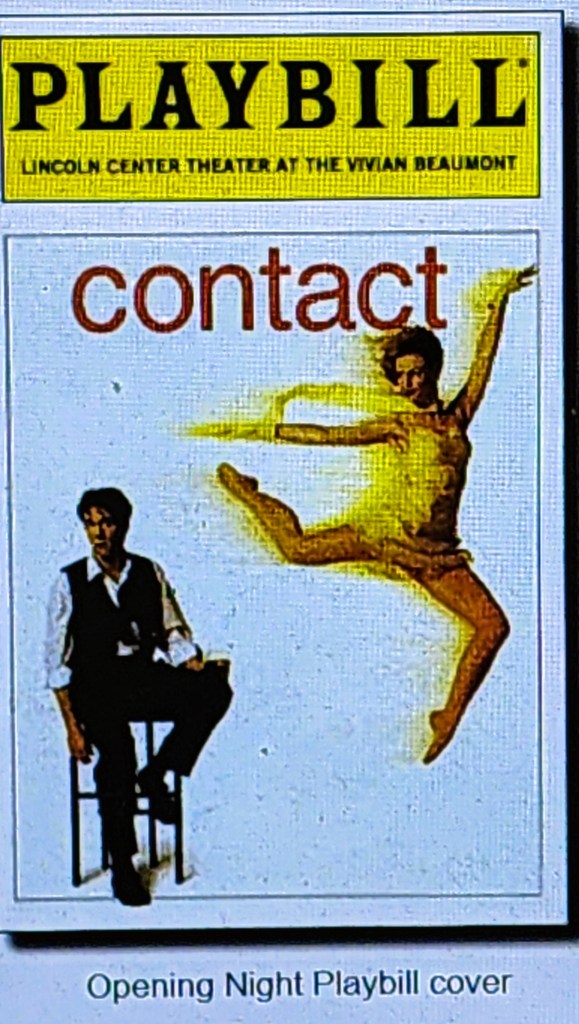

Past exceptional productions include her direction and choreography for The Producers (12 Tony Awards including Best Direction and Best Choreography). She co-created, directed and choreographed the Tony Award-winning musical Contact for Lincoln Center Theater. She received a 2003 Emmy Award for Live from Lincoln Center. Broadway credits include Oklahoma!, Show Boat, Prince of Broadway, Bullets Over Broadway, Big Fish, Young Frankenstein, The Music Man and others. Her Off-Broadway Credits include The Beast in the Jungle, Dot, and Flora the Red Menace to name a few.

Stroman has experience with ballet and opera

She garnered additional theater credits and to these add ballet and opera which include The Merry Widow (Metropolitan Opera); Double Feature, and For the Love of Duke (New York City Ballet). She received four Golden Globe nominations for her direction and choreography for The Producers: The Movie Musical. Additionally, she is the recipient of the George Abbott Award for Lifetime Achievement in the American Theater, and an inductee of the Theater Hall of Fame in New York City. For her complete list of accomplishments, credits and awards, go to www.SusanStroman.com

After Washington and Stroman discussed her beginnings growing up in Delaware in a house of music, where she danced and was in dancing school, she would always create dances when her father played the piano. She grew up appreciating her father’s storytelling and musical talent. She majored in English at the University of Delaware and was attracted to story telling and its different forms which, of course, included music and dance. She mentioned that her family would watch movie musicals together on their sofa, and as she watched, she intuited the synchronicity between the dance and the music and the feeling it created. Storytelling through the dance came easily to her because of her parents and their appreciation of musicals, music, movement and how dancing conveyed the story.

Choreography helps to move the plot forward

For Stroman, today, especially with the virtual media environment, choreography is imperative for moving the plot and story forward in immediacy. The audience wants the story to move forward constantly, which can be accomplished with choreography transitioning the turning points so the events have a forward momentum. In recognizing the importance of the staging and the dance, every corner of the stage must be considered. There is no empty part of the stage that doesn’t have the element of storytelling through dance, music and dialogue.

It is a testament to Stroman’s ability to continually provide fascinating visuals, color and movement so entrancing to audiences, who love her work, if sometimes critics don’t fully understand or appreciate the genius she displays. Indeed, with the stage beginning as a writer begins with a blank page, Stroman thinks profoundly about every dancer, every performer, every musical note, every word of dialogue and of course all the elements in the story (Aristotle’s poetics).

For my mind, her works should be studied in musical theater classes in universities for their immediacy, their vibrance, their emotional grist and their coherence as they synchronize elements of scenic design, costume design, and hair and wig design, lighting, sound, to effect the beauty, sorrow, majesty of the story being told.

The film The Sound of Music was an influence

Stroman emphasized that she and her brother saw The Sound of Music together and it impacted her understanding. She stated, “I was blown away by that movie. I guess I was twelve.” She couldn’t believe the story that was being told and how important the story was, realizing it could be something which is really profound. Stroman followed with the idea that she visualizes music with a story following along. Additionally, she imagines how the dancers would be dancing. Immediately, her “brain begins to spin about what story is being told through the music, the instrumentation and the orchestrations.”

When Stroman puts a show together, she “works very much with the show’s composer and arranger,” of how to open up the music. She manipulates the time signature of the music to help represent the emotion she wants the actors to play and to move forward the momentum of the story. She does a lot of research on every musical. This might include the history of the decade, the geographical area, the setting. She immerses herself in research and thinks extensively about the characters. This helps to inform how she choreographs the music.

Working with performers is about collaborating in a safe space.

Working with actors is about collaborating in a safe space. First, comes the research. Then comes the time and effort put into using what has been learned. Washington attested to Stroman’s being there early before everyone else, and staying late after everyone was gone. Stroman works extensively with her musical partners. Additionally, she is aware of the actor’s process. Each have their own process. Some pick up elements very quickly and others don’t. It is a balancing act to get all on the same page and not make them feel inferior.

In making sure all feel comfortable in the learning process, Stroman stays positive and roots for her actors, wanting them to do their best. Getting the performers to the point of excellence, she has to do her research and be prepared before she ever creates the safe space in the rehearsal room. When they arrive there together, she’s worked through almost the entire show. However, part of creation and allowing the cast to feel comfortable, she doesn’t share all of what she knows. She wants them “to feel free” and be creative and “feel a part of it.” She’s also inspired by the performers who come up with their own creative suggestions. She allows for actors and dancers’ agency, encouraging them to try something different.

Stroman collaborated with Washington during the production, Dot

Stroman shared a moment in Dot where Sharon Washington’s character had extensive monologues and she gave her the stage action of cooking eggs. Stroman had Washington pace the dialogue with cooking eggs so that she finished every time on a particular word. Though Washington was skeptical at first, she become so attuned, that the timing was perfect. With Stroman’s encouragement, she finished when the eggs were done and landed precisely on the designated “word” in the monologue. Both Stroman and Washington discussed the wonder of creating something that didn’t exist before. Considering all the people that collaborated in the creation, the artistry of that collaboration to present something amazing is miraculous.

Stroman discussed how the ideas for various scripts or stories come from various places. The seminal idea for the show Contact came surprisingly with the image of the girl in the yellow dress. Stroman discussed that she was in a bar at one in the morning, and in a bar where all the New Yorkers wore black. And “in walked this girl with a yellow dress which I thought was quite bold for one in the morning.” Stroman described the girl’s action, “She would step forward when she wanted to dance with somebody, and then she would retreat back when she was done with them.” According to Stroman, she was an amazing dancer and she was only there to dance. Stroman watched her dance with various men. Then she disappeared into the night.

The girl with the yellow dress becomes Contact

Around two weeks later at Lincoln Center, Stroman was approached about having ideas. She said, “You know, I think I have an idea.” And from then on, the story of the girl in the yellow dress took flight, bringing in all the elements of music, dance, and storyline. That’s how Contact came into existence, from a visual and organic, raw experience that stirred Susan Stroman’s imagination. Amazing! Contact ran for three years. Humorously, Stroman discussed how pictures of the “girl in the yellow dress” were on busses and billboards and she was thinking the girl would come forward and say something. She never did.

Stroman shared another story about the time she met with Mel Brooks. She was working on A Christmas Carol when she received a call to meet with Mel Brooks. Familiar with his work, she wondered what he wanted to talk to her about. There was a knock at the door. And when she opened it, he started singing, “That face, that face…” and he danced down Stroman’s long hallway, then jumped up on her sofa and said, “Hello! I’m Mel Brooks.” Stroman shared that she didn’t know what would happen. She thought, “But whatever it is, it’s going to be a great adventure.” Indeed, the experience was, “the adventure of a lifetime.”

Regarding working with Mel Brooks, Stroman suggested that she learned from him, collaborating and observing. Of course, it was a new art form for him, so he was flexible and learned from Stroman’s theatrical experiences and process of working. It appears they developed a mutual admiration society.

Facing obstacles as a woman

Washington asked about the obstacles Stroman faced as a women. When Stroman got in the business, she stated, “It really was male dominated.” And she mentioned that it has only been in the last fifteen years that there have been women directors. However, she was not certain about “why that is or was.” When she started, she wanted people to believe, “In the art of what I was doing.” She didn’t dress up. She wore a baseball cap. At that time there was a pressure to “dress down,” and be “strong, but not too strong.” Stroman felt like she “could do it,” when she came to New York. However, she didn’t know if she would “be allowed to do it.”

In sharing a story to encourage young people or anyone in the business, she suggested “always ask questions.” The worst that can happen is that “they” say “no.” One day she and another actor were throwing out ideas and came up with the idea to approach Cabaret’s Kander and Ebb and ask if they could take one of their shows and direct and choreograph it for Off-Broadway. They were shocked when Kander and Ebb agreed and they took Flora the Red Menace, reworked it and brought it to The Vineyard Theatre.

Critics

Stroman discussed critics. She mentioned that “bad reviews are very hurtful.” She also suggested that women’s work is more harshly criticized than men’s and that the same applied in politics. She referenced her great disappointment that New York, New York didn’t have staying power and closed. They were waiting for the tourists, but they never came. Regarding the collaboration, she enjoyed working with the creative team tremendously. Of course, that made the show not lasting more poignant. The show received positive and negative reviews. Regarding any positive reviews received over the years, Stroman quipped, “The good reviews are never good enough.” And when there’s a great review, “You think, well, why didn’t they talk about that?” You just “have to feel good about what you are creating,” she insisted.

In discussing mentorship Sharon Washington suggested Stroman is very gracious and lets everyone participate. With every show she does, she usually has “A young observer who comes on the show and they get to be there for the whole process.” She said, “It’s important to be in the room where it happens.” Young people learn best when they see the process unfolding and join in it, participating whenever it is feasible. They learn, then, that it’s a collaboration. As the team works together, the director coheres with all the designers. It is the director, who has a clear vision of what the production should be. Then, the director shepherds the creatives and negotiates through and around the various egos.

For more on Susan Stroman https://www.susanstroman.com/ or Sharon Washington https://iamsharonwashington.com/ go to their websites. For a video of the interview, visit the New York Library for the Performing Arts archive in person.

The League of Professional Theatre Women is a membership organization for professional theatre women representing a diversity of identities, backgrounds, and disciplines. Through its programs and initiatives, it creates community, cultivates leadership, and seeks to increase opportunities and recognition for women in professional theatre. Its mission is to champion, promote, and celebrate the voices, presence and visibility of women theatre professionals and to advocate for parity and recognition for women in theatre across all disciplines.