Blog Archives

‘Archduke,’ Patrick Page and Kristine Nielsen are Not to be Missed

What is taught in history books about WWI usually references Gavrilo Princip as the spark that ignited the “war to end all wars.” Princip and his nationalist, anarchic Bosnian Serb fellows, devoted to the cause of freeing Serbia from the Austro-Hungarian empire, did finally assassinate the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess of Austria-Hungary. This occurred after they made mistakes which nearly botched their mission.

What might have happened if they didn’t murder the royals? The conclusion of Rajiv Joseph’s Archduke offers a “What if?” It’s a profound question, not to be underestimated.

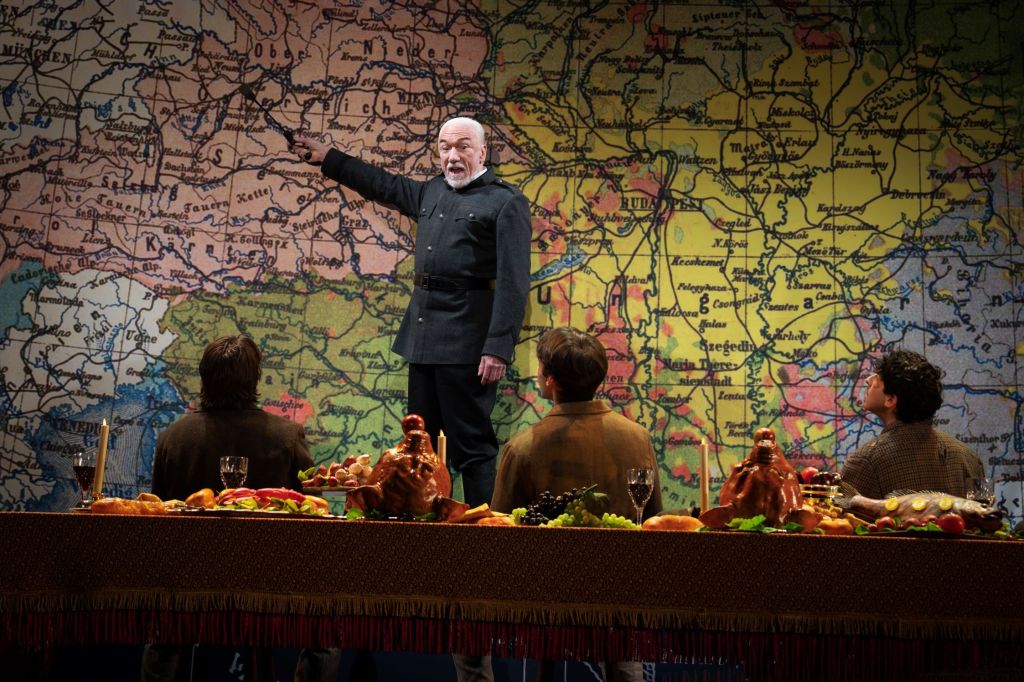

In Archduke, Rajiv Joseph (Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo), has fun with this historical moment of the Archduke’s assassination. In fact he turns it on its head. With irony he fictionalizes what some scholars think about a conspiracy. They have suggested that Serbian military officer Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic (portrayed exceptionally by Patrick Page), sanctioned and helped organize the conspiracy behind the assassination. The sardonic comedy Archduke, about how youths become the pawns of elites to exact violence and chaos, currently runs at Roundabout’s Laura Pels Theater until December 21st.

Joseph’s farce propels its characters forward with dark, insinuating flourishes. The playwright re-imagines the backstory leading up to the cataclysmic assassination that changed the map of Europe after the bloodiest war in history up to that time. He mixes facts (names, people, dates, places), with fiction (dialogue, incidents, idiosyncratic characterizations, i.e. Sladjana’s time in the chapel with the young men offering them “cherries”). Indeed, he employs revisionist history to align his meta-theme with our current time. Then, as now, sinister, powerful forces radicalize desperate young men to murder for the sake of political agendas.

In order to convey his ideas Joseph compresses the time of the radicalization for dramatic purposes. Also, he laces the characterizations and events with dark humor, action and sometimes bloodcurdling descriptions of violence.

For example in “Apis'” mesmerizing description of a regicide he committed (June, 1903), for which he was proclaimed a Serbian hero, he acutely describes the act (he disemboweled them). He emphasizes the killing with specificity asking questions of those he mentors to drive the point home, so to speak. Then, Captain Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic dramatically explains that he was shot three times and the bullets were never removed. Page delivers the speech with power, nuance and grit. Just terrific.

Interestingly, the fact that Dimitrijevic took three bullets that were never removed fits with historical references. Page’s anointed “Apis” relates his act of heroism to Gavrilo (the winsome, affecting Jake Berne), Nedeljko (the fiesty Jason Sanchez), and Trifko (the fine Adrien Rolet), to instruct them in bravery. The playwright teases the audience by placing factual clues throughout the play, as if he dares you to look them up.

History buffs will be entertained. Those who are indifferent will enjoy the fight sequences and Kristine Nielsen’s slapstick humor and perfect timing. They will listen raptly to Patrick Page’s fervent story and watch his slick manipulations. Director Darko Tresnjak (A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder), shepherds the scenes carefully. The production and all its artistic elements benefit from his coherent vision, his superb pacing and smart staging. Set design is by Alexander Dodge, with Linda Cho’s costume design, Matthew Richards’ lighting design and Jane Shaw’s sound design.

In Joseph’s re-imagining before “Apis” delivers this speech of glory and violence, the Captain has his cook stuff the starving, tubercular, young teens with a sumptuous feast. As they eat, he provides the history lessons using a pointer and an expansive map of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Like brainwashed lap dogs they agree with him when he tells them to. They are inspired by his personal story of glory and riches, and the luxurious surroundings. Notably, they become attuned to his bravery and sacrifice to Serbia, after their bellies are full, having devoured as much as possible.

Why them and how did they get there? Joseph infers the machinations behind the “Apis'” persuasion in Scene 1, which takes place in a warehouse and serves as the linchpin of how young men become the dupes of those like the charming, well-connected Dimitrijevic. From the teens’ conversation we divine that a secret cabal cultivates and entraps desperate, dying young men. Indeed, in real life there was a secret society (The Black Hand), that Captain Dimitrijevic belonged to and that Gavrilo was affiliated with. The playwright ironically hints at these ties when the Captain gives Gavrilo and the others black gloves.

In the warehouse scene the soulful and dynamic interaction between Berne’s Gavrilo and Sanchez’s Nedeljko creates empathy. The fine actors stir our sympathy and interest. We note that the culture and society have forgotten these hapless innocents that are treated like insignificant refuse. As a result they become ready prey to be exploited. The nineteen-year-old orphans have similar backgrounds. Clearly, their poverty, purposelessness, lack of education and hunger bring them to a conspiratorial doctor they learn about because he is free and perhaps can help.

However, he gives them the bad news that they are dying and nothing can be done. As part of the plan, the doctor refers both Gavrilo and Nedeljko to “a guy” in a warehouse for a job or something useful and “meaningful.”

True to the doctor’s word, the abusive Trifko arrives expecting to see more “lungers.” After he shows them a bomb that doesn’t explode when dropped (a possible reference to the misdirected bombing during the initial attempt against the Archduke), Trifko browbeats and lures them to the Captain (“Apis”), with his reference to a “lady cook.”

Why not go? They are starving, and they “have nothing to lose.” The cook, Sladjana, turns out to be the always riotous Kristine Nielsen, who provides a good deal of the humor during the Captain’s history lessons, and the radicalization of the teens, the feast, sweets, and “special boxes” filled with surprises that she brings in and takes out. Nielsen’s antics ground Archduke in farce, and the scenes with her are imminently entertaining as she revels in the ridiculous to audience laughter.

With their needs met and their psychological and emotional manhood stoked to make their names famous, the young men throw off their religious condemnation of suicide and agree to martyr themselves and kill the Archduke to free Serbia. Enjoying the prospects of a train ride and a bed and more food, after a bit of practice, shooting the Archduke and Duchess, with “Apis” and Sladjana pretending to be royalty, they head off to Sarajevo. Since Joseph’s play is revisionist, you will just have to see how and why he spins the ending as he does with the characters imaging their own, “What if?”

The vibrantly sinister, nefarious Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijevic, who seduces and spins polemic like a magician with convincing prestidigitation, seems relevant in light of the present day’s media propaganda. Whether mainstream, which censors information, fearful of true investigative reporting, or social media, which must be navigated carefully to avoid propaganda bots, both spin their dangerous perspectives. The more needy the individuals emotionally, physically, psychologically, the more amenable they are to propaganda. And the more desperate (consider Luigi Mangione or Shane Tamura or the suspect in the recent shooting of the National Guard in Washington, D.D.), the less they have to lose being a martyr.

Joseph’s point is well taken. In Archduke the teens were abandoned and left to survive as so much flotsam and jetsam in a dying Austro-Hungarian empire. Is his play an underhanded warning? If we don’t take care of our youth, left to their own devices, they will remind us they matter too, and take care of us. Political violence, as Joseph and history reveal, is structured by those most likely to gain. Cui bono? All the more benefit of impunity and immunity if others are persuaded to pull the trigger, cause a riotous coup, release the button, poison, etc., and take the fall for it.

Archduke runs 2 hours with one intermission at Laura Pels Theater through December 21st. roundabouttheatre.org.

‘Hadestown,’ Broadway’s Tone Poem is an Epic, Illuminating Triumph

André De Shields in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics, Book by Anaïs Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

The ending spirals into the beginning, spirals into the ending. And so it goes in Hadestown, the magnificent production by Anaïs Mitchell (Music, Lyrics, Book), and Rachel Chavkin (Direction and Co-development with Mitchell) currently at the Walter Kerr Theater after transferring from other production iterations at the National Theatre, U.K. and NYTW in New York.

Hadestown is a breathtaking journey, into a phantasmagorical world whose musical pageantry and flickering contrasts between revelatory light and atmospheric darkness vibrate to one’s core. The spiritual themes of the play are rife; the irony of life in death (living to die) and death in life (dying to live) resonate for all time. Mitchell and Chavkin adroitly reshape the well-known love myth of Orpheus and Eurydice to parallel it with the equally compelling love myth of Persephone and Hades: Ancient Greece’s metaphoric visions of the immutable power of death, and the mutability of earthly life reflected in the seasons.

Hermes, the lightening-speed god who operates as our guide, negotiates the realms of the earth and spirit for us. We hop on his quicksilver wings of imagination and go along for the death-defying ride to return to earth wiser, perhaps. As Hermes, the inimitable André De Shields transforms into the phenomenal, captivating messenger.

Eva Noblezada and the Broadway cast of ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book by Anaïs Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

With measured grace he combines forceful power with smooth cool. He counsels, philosophizes, warns us in verse and song of an ancient story. It is the story of how the power of love and faith overcome death. And how the fates (the fabulous Jewelle Blackman, Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer, Kay Trinidad in patterned black/white outfits) influence the outcome using fear, doubt and the inherent tragedy of the human condition. Look for their signature song which they beautifully croon to Eurydice who echoes their response (“Any Way the Wind Blows”).

De Shields’ lovable chronicler looks dapper in a silver sharkskin suit with slivery slips on his sleeves which suggest wings courtesy of Michael Krass’ symbolic, well-thought out costume design. (Krass’s costumes enhance the characterization and themes throughout.) De Shields’ moves and manner are so easy, we risk the mysterious train ride with him through light and darkness on the journey to Hadestown and are introduced to all those who play a part in his chronicle of gods and men, life and death, material and supernatural forces (the “Road to Hell”).

(L to R): Jewelle Blackman, Kay Trinidad Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer, Music, Lyrics & Book by Anais Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

Mitchell’s and Chavkin’s amazing reconfiguration of these myths is powered by vibrant, musically diverse and multilayered songs and spoken verse. These combine to reveal how climate change has gravely misaligned the world that the characters live in. Chavkin and Mitchell evoke fitting metaphoric parallels with the myths of mutability and immutability. Orpheus and Eurydice become central characters interwoven in the fabric of the play: its action, conflicts, arc of development, symbols, themes.

On the material plane, the situation is dire. Upended by fires, floods and extreme cycles of heat and cold with storms that are off the categorical charts, the earth provides no succor for its inhabitants, many of whom are destitute and dying. Forced into a gypsy lifestyle, outrunning starvation and weather extremes as resources become scarce, migrants like Eurydice (the golden voiced Eva Noblezada) face an arduous, spooky ride to Hadestown unless they manage to get to the next day. Theirs is an existence of slow starvation, chronic sickness, sexual abuse and torment.

Eva Noblezada, Reeve Carney, André De Shields, Music, Lyrics, Book by Anaïs Mitchell, Developed with & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

For the haves like Orpheus (Reeve Carney’s naiveté, “touched” grace and beautiful tenor shine throughout) whose ancestor is a Muse and whose life is anointed by the protection of Hermes, the situation is less bleak. Orpheus has a roof over his head and a menial job in a haunting, ambience-rich, New Orleans-like jazz club, a way-station where the customers are soothed by the music of Dixieland before they continue on with the struggles of their miserable lives or elect to ride the train on the “Road to Hell” and get off at the last stop, Hadestown..

It is in this charged, atmospheric, (the lighting is superb thanks to Bradley King) jazz/R & B/folk/pop joint, Orpheus encounters the stunning, waif-like Eurydice, who is blown in by the Fates (“Any way the Wind Blows”). He falls for her and attempts to entrance her with a song of love that will right the world and return spring and abundance to the planet. But Eurydice’s knowledge of the dire, doomed existence of humanity runs deep. She confronts him with the facts of starvation and reality of life’s sorrows. She asserts his song has no power. But as he sings, the generating force of the anointed melody stirs her. She realizes its greatness and tells him to finish the song. He reassures her of his love and vows the song will establish a shared brotherhood and prosperous peace (“Come Home With Me,” “Wedding Song”).

Mitchell and Chavkin use the evocation that Orpheus’ love song is an ancient melody Hermes gave him when he was young. They dovetail this concept into the second love myth of Persephone and Hades. “Epic I” sung by Orpheus and Hermes, reveals how the gods’ love “made the earth go round” and established the beauteous seasonal balance that few remember now that their world is dying. The implication is that Orpheus’ supernatural song will return the earth to its former glory, and Persephone will be present the full six months of the year to celebrate her powers above ground (“Livin’ It Up On Top”).

Amber Gray in ‘Hadestown,’ with the company, Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

With hope and determination that he can succeed because, as Hermes says, “he’s touched,” Orpheus and Eurydice pledge their forever love in the lyrical “All I’ve Ever Known.” Eurydice forgets the reality of starvation in the warmth of Orpheus’ embrace as she basks in the beauteous spring that Amber Gray’s feisty, ebullient Persephone brings, however, briefly.

The seasons shorten incrementally, reflecting the indelible impact of global warming and Hermes’ injunction of “times being hard.” Persephone’s wine celebration is cut even shorter. Hades’ ride to bring Persephone back to the underworld is foreshadowed in the gyrating rhythms, enthralling melodies, sharp lyrics of “Hadestown,” In this memorable titular song, Hermes, Persephone and the entire company indicate what’s causing the earth’s doom as they illustrate in movement and song what Hadestown is like in its symbolic reflection of its impact above ground.

The themes and plot development merge seamlessly as the love stories meld. Hades, the brooding mover and shaker and oppressed Persephone are brought into focus with intriguing twists. Overwhelmed with anxiety and the stress about growing his powerful underworld empire (precious metals, oil, and attendant industries), Hades has forgotten his youth and the joy of his love for Persephone. He’s dour, commanding; she’s his bored, unhappy, trophy wife. The underlying humor is ironic. He is supposed to be the terrifying, sexy god of the underworld and his wife is, in effect, kicking him out of her bed. Fearing he has lost her, Hades brings Persephone back to Hadestown earlier and earlier triggering weather extremes as the earth cannot adjust (“Gathering Storm”).

Eva Noblezada and the Broadway cast of ‘Hadestown’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

When Persephone leaves, weather devastation returns. Eurydice suffers her former hellish grind and panic. She searches for food and firewood, losing patience, dismissing Orpheus’s vows. While Orpheus feverishly works on the song (“Epic II”) she wanders in weariness and hunger. The conflicts intensify. The lure of Hadestown, the world apparently more stable than the cataclysmic earth in the song (“Chant”) trenchantly reveals the strident tensions between Orpheus and Eurydice.

Eventually losing her will to survive, doubting Orpheus’ ability to care for her, Eurydice becomes susceptible to Hades. He finds her fascinating because Persephone has cast him aside (“Hey Little Songbird”). When he offers Eurydice safety, security and freedom, she considers a visit to Hadestown for a bite to eat would be better than waiting for Orpheus in pain. What should she choose? Security and reliability below or starvation, slow torture and uncertainty above. Whether now or in the future, either decision will result in the final stop of her existence in Hadestown. What she does not consider is her will. It is one thing to struggle to survive, dying in the process. It is another to choose to die because it is too tough to go on.

Though this differentiation is inferred in the play, Greek Mythology carries it further. Souls who made good/beneficial choices on earth (they did not commit suicide) went to the Elysian Fields where they played all day: an equivalent of Paradise. Other souls who made harmful decisions were given their just due in the underworld. The souls in Hadestown fall into the latter category, laboring in the toil of the mines forever, in Mitchell’s and Chavkin’s version.

Reeve Carney and the Broadway cast of ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

As Eurydice considers her options, the Fates influence her with the fabulous, rhythmic “When the Chips Are Down.” (“Aim for your heart, shoot to kill, if you don’t do it, then the other one will”). Eurydice chooses her destiny, allowing material necessity and her flesh to overwhelm her. As she embraces Hadestown’s certainty, she cries out for Orpheus as the Fates admonish the audience that they would do the same as she, if they were in her shoes, in the superb song (“Gone, I’m Gone”).

Eurydice affirms she’ll return (“Wait For Me”) then travels to the underworld lowered into the darkness as ominous clouds of smoke billow up with intimations of flames and intense heat. Orpheus finishes his song, but it’s too late; Eurydice has gone into hell. Hermes guides him along a secret alternate route to Hadestown as Hermes, Orpheus, Fates and the ensemble sing that Orpheus comes for her in the lyrical, powerful ending of “Wait For Me.”

These scenes are uniquely staged, with dynamism and excitement; the lighting enhances throughout. The tension builds to the final revelatory scene in Act I which uncovers Hades’ terrifying realm. The revolving platforms move clockwise and counterclockwise as the ensemble and Orpheus move in the opposite direction. Time reverses and changes course as Orpheus walks with fierce determination to the underworld.

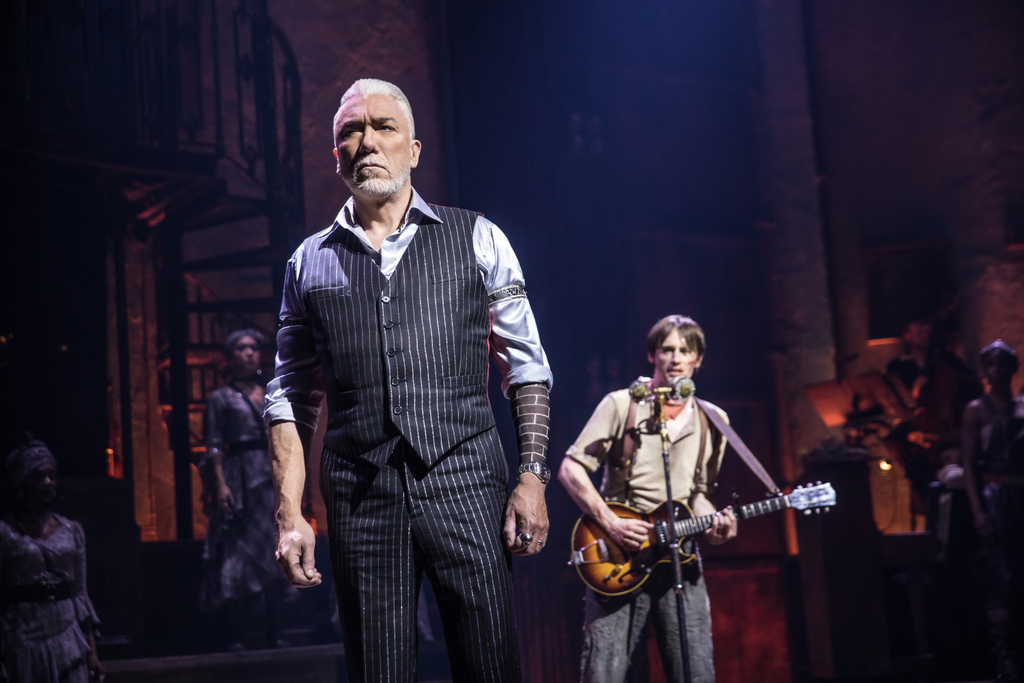

Patrick Page (foreground) Reeve Carney (background) in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

The circularity of movement is rich with profound meaning. For example, we make repeat wrong decisions, doing the same thing over and over again with dire consequences This theme suggests the oblivion of Hadestown, (its boring factory sameness) and the waning vitality of Hades. His repeated bad decisions result in the imprisonment of himself, his workers and Persephone, the goddess of change, who abhors the drudgery of the same old same old. Hades has so brainwashed himself, he’s convinced they are free while they are in oblivion as they work like slaves (today’s corporate erosion of worker’s rights…see the film American Factory)

The pounding, thematically “earth-shattering” brilliant song, “Why We Build the Wall” sung by Hades, Persephone and the company is a sardonic paean to wall builders everywhere. The song is Hades’ stubborn justification for his misery, self-torment and the loss of his youth while amassing an empire. By building the wall he and workers he refers to as his “children” keep out the fear of uncertainty and want. They are secure in their never-ending work as they war against deprivation. What he seeks to avoid, he brings upon the entire planet in a self-fulfilling prophecy swaddled by fear. There is only one way to break down the wall: restore Hades’ and Persephone’s love. His fear of losing her will end and he’ll allow her to restore the earth in the natural balance of the seasons. Orpheus must sing his anointed, ancient love song to restore Hades to himself and Persephone, and restore Eurydice to his arms and life.

Patrick Page, Amber Gray in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

As Hades, Patrick Page’s eminence is superbly realized in his demeanor, walk, voice and appearance. Page’s Hades is a charismatic warlord who sports his sleek brand of “mellow cool” in a gangster-ish pin stripped suit and styled comb-up. His organic, spot-on portrayal makes him human and empathetic. Though he is a god, he fears his adoration of Persephone (“Chant”) is jealous of her absences, and looks for comfort in someone new (“Hey, Little Songbird”). Page’s portrayal is spot-on, mesmerizing.

Amber Gray’s Persephone is an energetic, sun-filled presence. She blooms with razz-ma-tazz vitality above ground but turns it around as an upside down gal in the bleak underworld appropriately dressed for a perpetual funeral. Like the rest of the principals in the ensemble, she is just smashing. Carney’s Orpheus and Noblezada’s Eurydice sing with the lyricism inherent in their gorgeous vocal instruments. They permeate their songs in the second act with soulful, aching beauty, breathing life into the score and lyrics. But then so do Hermes/De Shields (Wow!) Hades/Page (Good gracious!) Persephone/Grey (Yes, ma’am!)

Reeve Carney, Eva Noblezada in ‘Hadestown,’ Music, Lyrics & Book Anaïs Mitchell, Developed & Directed by Rachel Chavkin (Matthew Murphy)

Act II brings the fullness of the plot development, themes and characterizations/gods/lovers that Hermes has so familiarized us with, we’ve come to adore them as family. The song lyrics and music are standouts and build upon what’s been threaded before. You will walk away humming the tunes, drumming the beats. Orpheus’ journey to Hadestown is paced frenetically, with foreboding danger as he moves with stylized grace through his mind of doubt and fear. The use of lighting is sensational and thrilling especially during this sequence (thanks, Bradley King). And at the end, well it’s De Shield’s moment. He stands rooting us in mankind’s tragic history, as the ensemble joins him in soaring song that will be sung over and over again. Ineffable.

This is the type of production that is so jeweled, one will appreciate it in the second seeing or third. You will catch nuances here, symbols there, effects, songs, movements, so much of what your sleight of mind may have missed the first or second time around. All of it is soul careening. This rare production thrums with poetic grace and ancient rhythmic currents that resonate profoundly, irrevocably with life. And occasionally what peers out at us in this play from the other side reminds us of…

Kudos to the creatives who measured the symbols of characterization and themes to synergistically meld them with stylistic, adroit artistry into the play’s fantastic spectacle: Rachel Hauck (Scenic Design) Michael Krass (Costume Design) Bradley King (Lighting Design) Nevin Steinberg, Jessica Paz (Sound Design) Hudson Theatrical Associates (Technical Supervision) Michael Chorney, Todd Sickafoose (Arrangements and Orchestrations).

The music and lyrics are unparalleled, thrilling, coherent. Mitchell and Chavkin, the ensemble and creatives have wrought a divine work for the ages. Surely it is a multiple award winner. Hadestown runs with one intermission at the Walter Kerr Theater (219 West 48th St.) For tickets go to their website by CLICKING HERE.