Blog Archives

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

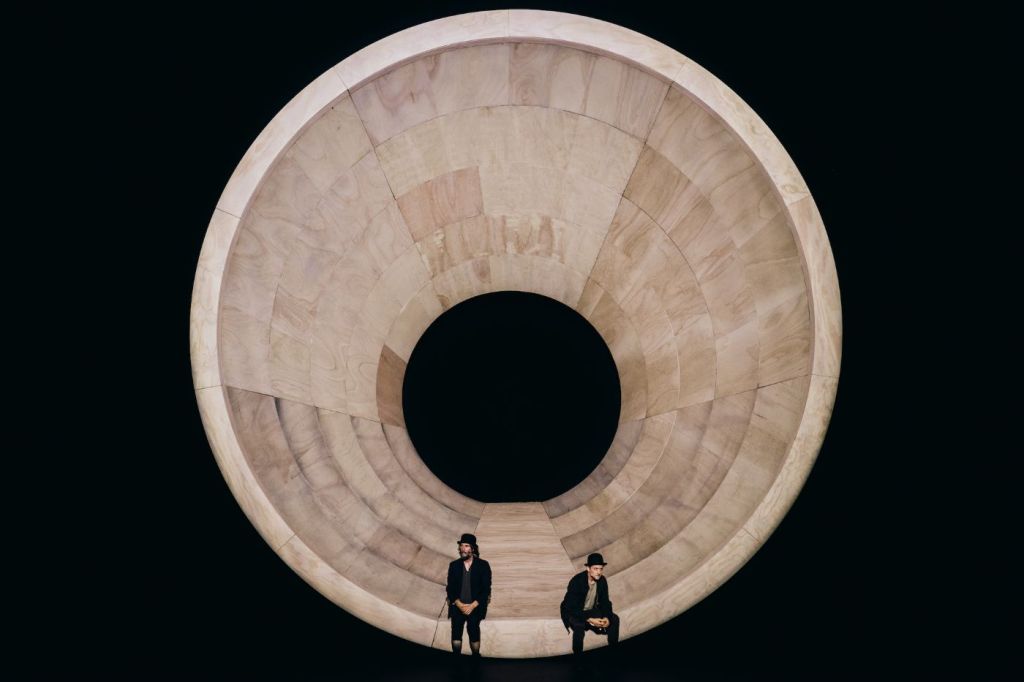

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.

Caryl Churchill Strikes Again in a Provocative Suite of Metaphoric One-acts: Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Metaphor rides high in the four one-act offerings thematically threaded by British playwright Caryl Churchill. The suite is currently playing at The Public Theater until May 11th. Directed by James Macdonald, Churchill’s most recent collection integrates poetry, surrealism and “mundane reality” with a twist to represent the precariousness of our psyches in an incomprehensible world that populates the humorous and the horrible simultaneously.

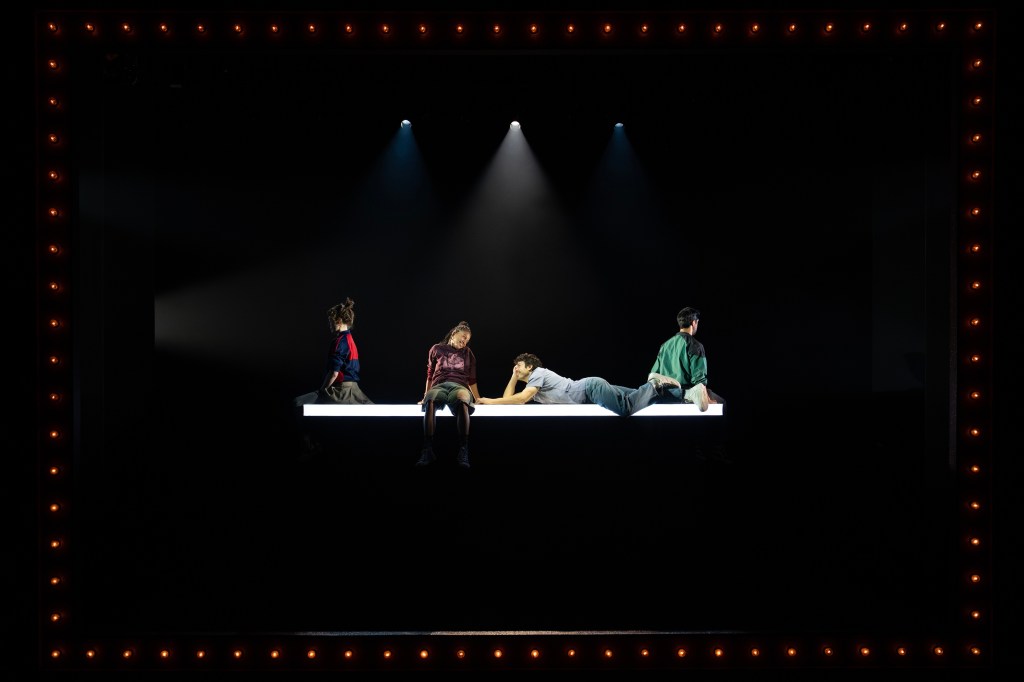

“GLASS” is a fairy-tale-like playlet that opens onto a lighted platform amidst darkness (scenic design by Miriam Buether), which we discover is a mantlepiece that holds objects. The protagonist is a girl of transparent glass (AyanaWorkman). According to the stage directions, “There should be no attempt to make the glass girl look as if she is made of glass. She looks like people look.” We meet her with others who are her jealous rivals, (an antique clock, a plastic red dog, a vase). Though the “glass girl” doesn’t seem to care to compete, the others humorously swipe at each other about who is the most useful, beautiful or valuable.

All look like people, suggesting a conceit. One interpretation might be that objectified humans come to believe in their own “grand” objectification. Other humans, aware of themselves, are transparently fragile, which can result in tragedy. Though Churchill’s meaning is opaque, the playwright adds layers. When Ayana Workman’s character is with schoolgirls, who persecute her and make her cry, her pain is visible both inside and out. Her vulnerability attracts a boy (Japhet Balaban), who becomes her friend and confidante. He whispers a story of his life with his father since he was seven. Though his whispers are not audible, we imagine the worst. Yet, we are shocked when the glass girl explains what happens to him which has a devastating impact on her.

The theme of fragility suggested in “GLASS,” is continued as an ironic reversal in “GODS,” after circus performer Junru Wang, presents stunning acrobatic maneuvers on handstand canes. The interlude with lyrical music provides time to reflect about aspects of life which require balance that only comes with training and practice as Junru Wang exhibits.

In “GODS,” Churchill casts the Gods of Greek and Roman mythology as the vulnerable ones. They unleashed the Furies to punish brutal humankind to no avail, then recalled them because humans never tire of bloodthirsty murders, wars, rampages. Deirdre O’Connell embodies all of the Gods. She sits suspended mid stage on a fluffy, white cloud surrounded by darkness, haranguing the audience in a stream of consciousness rant about the bloodletting, familial murders, intrigues, wars and cannibalism.

In a summary of bloody acts, O’Connell’s Gods admit they encouraged the brutality with curses and liked watching the results. But now in a humorous and ironic twist, they don’t like it. Furthermore, they wash their hands of the killing, because they don’t even exist. That is to say humans attribute their own monstrous behavior to the Gods instead of accepting responsibility for their own heinous acts. By the conclusion O’Connell’s Gods scream and plead, “He kills his son for the gods to eat and we say no don’t do that it’s enough we don’t like it now don’t do it we say stop please.” The Gods’ point is made. The audience agrees. The maniacal being, a human creation, haplessly protests its creators, knowing the bloodshed and murders will continue. If the gods had ultimate control would humanity be peaceable? Churchill’s irony is devastating.

Circus performer Maddox Morfit-Tighe creates the second interlude as he juggles with clubs and performs acrobatic movements. Macdonald positions both circus performers in the “pit” in front of proscenium using Isabella Byrd’s lighting design for dramatic effect. Churchill’s irony about humankind as performers who juggle and balance themselves in the tragicomical circle of life continues the thematic thread of vulnerability and fragility.

In “WHAT IF IF ONLY” a husband’s (Sathya Sridharan) grief over his wife’s death is so intense that his desire touches the spiritual realm, and the possibility of her return seems imminent when a “being” shows up. However, his suffering has evoked a ghost of “the dead future.” The being brings the horrific understanding that his wife is forever gone, subject to her vulnerable mortality. What is left are the illimitable future possibilities. But when the being suggests that he tries to make a possibility happen, he claims he doesn’t know how. His grief has cut off his ability to even conceive of a future without his wife.

No matter, a child of the future (Ruby Blaut), shows up. Though he ignores the child, she affirms she is going to happen. As we daily ignore our vulnerable, mortal flesh to live, the future will happen, until we die. Churchill frames life as hope with possibility that we must let happen.

After the intermission Macdonald presents Churchill’s uncharacteristic, humorously domestic one-act “IMP.” The last play continues the thematic threads but buries them in the ordinary and humorous. The significance of the title manifests well into the play development after we learn the back story of two cousins who live together, Dot (O’Connell), and Jimmy (John Ellison Conlee), and their two visitors, niece Niamh (Adelind Horan), from Ireland, and local homeless man Rob (Japhet Balaban). During Rob’s visit with Jimmy, since Rob doesn’t want to discuss any personal details about himself or the possibility of a relationship forming between himself and Niamh, Jimmy decides to share a family secret. Dot believes she captured an imp that is in a wine bottle capped with a cork.

Though Jimmy claims not to believe the imp exists, at Bob’s suggestion, he uncorks the bottle. In the next six scenes we watch to see if anything changes in the lives of these individuals and are especially appalled when Dot wishes evil on Rob via the imp when she discovers that Niamh and Rob split up. We discover the imp’s power by the conclusion. However, the act of Dot’s powerlessness and vulnerability in projecting her own malevolent wishes through a mythic creation to avenge a loved one is pure Churchill. This is especially so because in this homely environment where nothing unusual happens, there is the understanding that people activate myths. Indeed, our beliefs may comfort, but on another level may entrap and even destroy.

Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Running time is 2 hours15 minutes with one intermission, through May 11th at the Public Theater publictheater.org.

Bill Irwin in ‘On Beckett’ at the Irish Repertory Theatre, Off Broadway Review

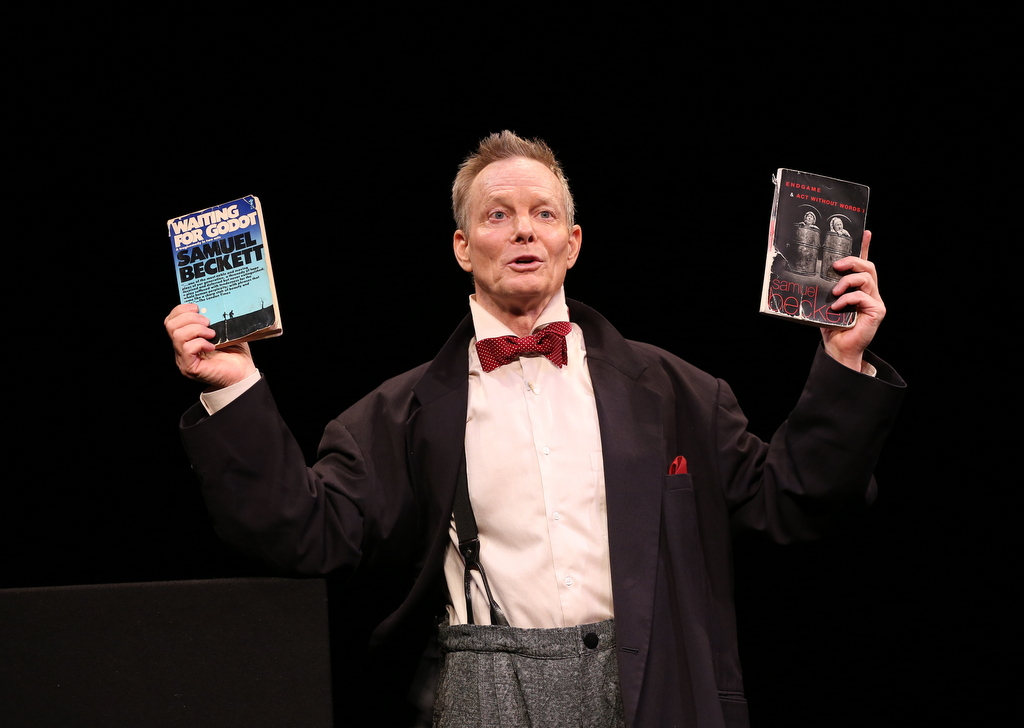

Bill Irwin, ‘On Beckett: Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett,’ Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Has there ever been a more elegant, erudite and riotously funny clown prince of theater than Bill Irwin? Not only has the Tony Award winner mastered the innards of pacing, rhythm, mime, body visualizations and timing of the comedic. Irwin writes, directs, acts. What does he not do well theatrically and dramatically? In what he attempts, Irwin delights. In his On Beckett at the Irish Repertory Theatre, Irwin examines the opaque and timeless works of Nobel Laureate Samuel Beckett. What an exquisite evening Irwin conceives, directs and performs.

On Beckett: Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett introduces us to lesser-known works, and he revisits the often performed Waiting For Godot with the assistance of Finn O’Sullivan as the boy. Irwin appeared in the 2009 production of Godot and received a Drama Desk Award nomination.

As he presents Beckett’s less familiar writings, he acknowledges the importance of the playwright’s Irish voice, identity, and heritage. Notably, Irwin showcases passages from Beckett’s elusive Texts For Nothing (13 short prose pieces), pointing out that Beckett wrote the arcane prose pieces in French, then translated them into English, his native tongue that Irwin identifies as the “familiar familial voice.” As an Irishman writing in French, Beckett maintained his uniquely Irish ethos but received widespread acceptance in France initially. The irony astounds as it is “the product of a complex translation exercise.”

The prose pieces Irwin performs, #1, #9, and #11, are masterworks about being, absence, presence, and vacancy, all interior dialogues and questions. They reveal the common man/woman’s struggle with self in a massive inner argument that represents individual consciousness. And they reveal the human condition of impoverishment, failure, exile, loss. In the passages Irwin selects, Beckett wrangles the concept of consciousness. Indeed, these excerpts reveal the act of viewing oneself in despair, in parallel with the self experiencing despair.

(L to R): Finn O’Sullivan, Bill Irwin in ‘On Beckett: Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett,’ Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg).

Thus, from both perspectives Beckett suggests questions about existence, survival, struggle, and purpose. The will “not to go on” while “going on” remains paramount in Beckett’s darkest, bleakest comedy. These elements Irwin melds with the cliché of the Comic Irishman “who has waiting to do” and “struggles with the notion of ease, and his placement in the larger scheme of things.”

In his comments before and after excerpts from Beckett’s novels The Unnamable and Watt, Irwin questions: “Is he making fun of the way consciousness works?” Or “is he offering a portrait of consciousness?” As we appreciate this rare experience that Irwin delivers with aplomb, we understand Beckett’s extraordinary contributions. Not only did he assist in the transformation of English modernist literature, he was credited as integral to the Theatre of the Absurd along with Eugene Ionesco and Harold Pinter. Whether he would have appreciated the latter is debatable.

Notably, through his discussion we get to realize another facet of the diamond that is Bill Irwin’s artistry. In acting Beckett, he questions and appropriates the language and suggested meaning for himself. All of this pertains to and infuses his own relationship to art, acting, clowning, and theatrical expression. Shepherding us through Beckett’s language, Irwin ignites our passion. And he makes Beckett and perhaps ourselves more comprehensible in all the abstruse glory of the incomprehensible tragicomedy of life. Indeed, in his “Introduction” Irwin discusses how Beckett’s unforgettable words have gone viral within him, have haunted him. Certainly, the language resounds in his “head,” “heart,” “brain,” “mind,” “psyche,” “body.” This interesting admission yields that Beckett has been integral to Irwin’s evolution as a man and an actor, as a clown and an artist.

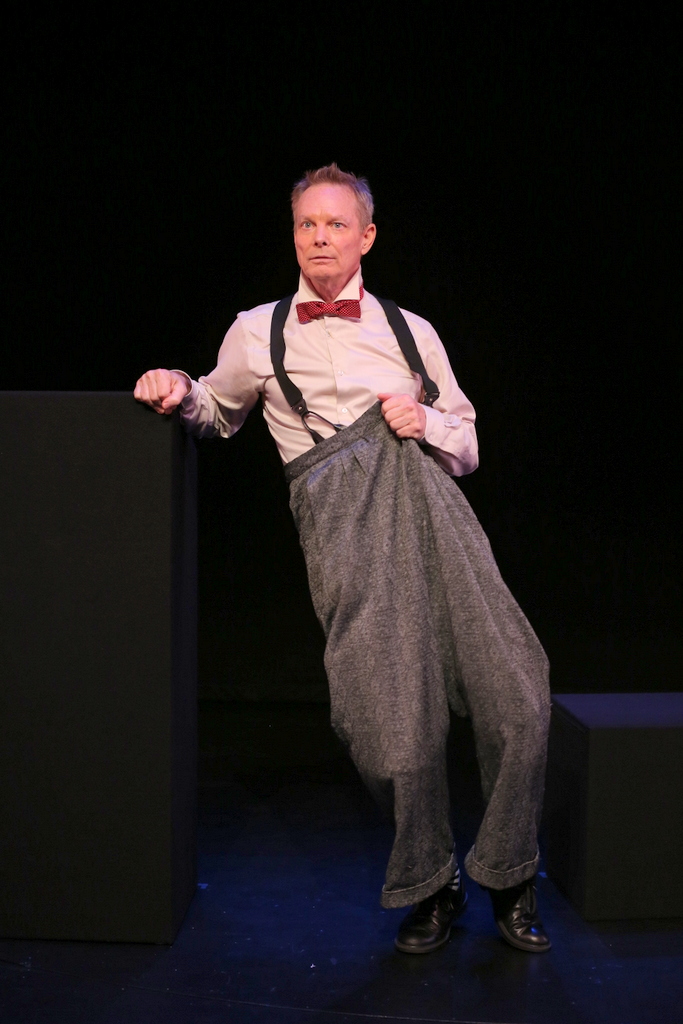

Bill Irwin in ‘On Beckett, Exploring The Works of Samuel Beckett,” conceived and performed by Bill Irwin at the Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Irwin’s comments sparkle with witty self-effacement. For example in outlining the evening, Irwin references the show lasting 86 minutes or so and quips, “I say this by way of reassurance.” Indeed, Beckett is not easy. But through Irwin’s humor we gradually become intrigued about his novel approach toward his subject and his singular recognition of Beckett’s language.

Irwin gets inside Beckett as an actor, and also explores his work from the perspective of clown theatrics. The great clown traditions, Irwin tells us, are “the lens through which he views everything.” And indeed, he applies this lens to exploring the extent to which he views Beckett as clown territory. Irwin’s hapless Clown characters and the techniques he employs to achieve this archetype everyperson provide the uplift to laugh at our shared humanity.

Revisiting Beckett from this unusual angle, Irwin’s organic acting and portrayal of Beckett’s clown characters enlightens. Cleverly, his performance and astute commentary about acting and language shine a beacon into Beckett’s mysterious obscure.

Kudos also go to Charlie Corcoran (scene design), Martha Hally (costume consultant), Michael Gottlieb (lighting design), and M. Florian Staab (sound design). Don’t miss seeing this wonderful presentation if you can get tickets. It closes on 4 November. Click here for the Irish Repertory Theatre website for times and tickets.