Blog Archives

‘Ragtime’ is Magnificent and of Incredible Moment

Between the time Lear DeBessonet’s Ragtime graced New York City Center with its Gala Production in 2024, until now with the opening of DeBessonet’s revival at Lincoln Center, our country has gone through a sea change. The very core of its values which uphold equal justice, civil rights and due process are under siege. Because our democratic processes are being shaken by the current political administration, there isn’t a better time to revisit this musical about American dreamers. Ragtime currently runs at the Vivian Beaumont Theater until January 4.

DeBessonet has kept most of the same cast as in the City Center Production. The performers represent three families from different socioeconomic classes. In each instance, they face the dawning of the 20th century with hope to maintain or secure “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” in a country whose declaration asserted independence from its king. In affirming “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all ‘men’ are created equal,” America’s promises to itself are fulfilled by its citizens. Ragtime reveals who these citizens may be as they strive toward such promised freedoms.

Above all Ragtime is about America, the saga of a glorious and terrible America, striving to manifest its ideals and live up to them, despite overarching forces that would slow down and halt the process.

Based on E. L. Doctorow’s classic 1975 historical novel, and adapted for the stage by Terrence McNally (book), Stephen Flaherty (music), and Lynn Ahrens, (lyrics), Ragtime‘s immutable verities are heartfelt and real. As such, it’s a consummate American musical. DeBessonet’s production celebrates this, and superbly presents the beauty, tragedy and hope of what America means to us. In its concluding songs (Coalhouse’s “Make Them Hear You,” and the company’s “Ragtime/Wheels of a Dream”), the performers express a poignant yearning. Sadly, their choral pleading is a stunning and painful reminder of how far we have yet to go to thoroughly uphold our constitution.

The opening number “Ragtime,” introduces the setting, characters and suggested themes. Here, DeBessonet’s vision is in full bloom, from the lovely period costumes by Linda Cho, David Korins’ minimally stylized scenic design, DeBessonet’s staging, and Ellenore Scott’s choreography. As the company sings with thrilling power and grace, they gradually move forward to take center stage. They are one unit of glorious interwoven diversity and destiny. The audience’s applause in reaction to the soaring music and stunning visual and aural presentation, heightened by a bare stage, emotionally charged the performers. Thematically, the cast had an important mandate to share, a cathartic revelation of the sanctity of American values, now on the brink of destruction.

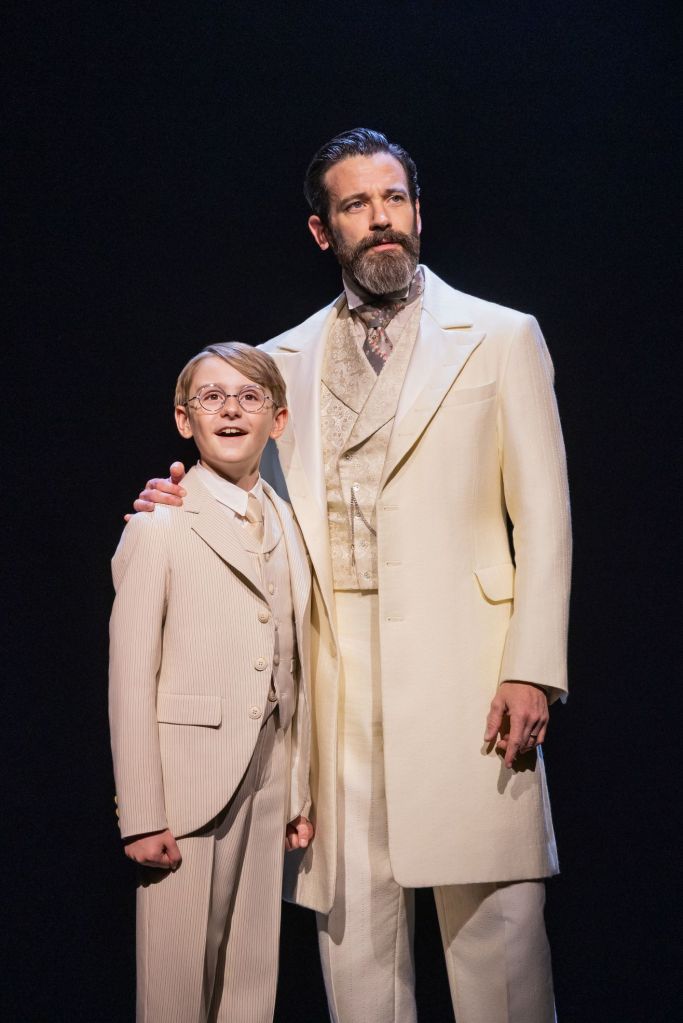

Watching the unfolding of events we cheer for characters like the talented Harlem pianist and composer of ragtime music, Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (the phenomenal Joshua Henry). And we identify with the ingenious, Jewish immigrant Tateh (the endearing Brandon Uranowitz). Tateh must succeed for the sake of his little daughter (Tabitha Lawing), despite their impoverished Latvian background. Likewise, we champion Mother (the superb Caissie Levy), who reveals her decency, kindness and skill, running the house, family and business. She must fill in the gap while her husband (Colin Donnell), goes on a lengthy expedition to the North Pole as a man of the privileged, upper class patriarchy.

The musical also reflects the other side of America’s blood-soaked history, best represented by characters along a continuum. Their misogyny, discrimination and greed often overwhelm, victimize and institutionalize innocents in the name of a just progress. These include tycoons like J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford, and the garden variety racists that brutalize Coalhouse Jr. and his partner Sarah (the fine Nichelle Lewis), in the name of order and security. Finally, to inspire all, the musical includes wily entrepreneurs like Harry Houdini (Rodd Cyrus), social justice advocates like Emma Goldman (the wonderful Shaina Taub), and accepted reformers like Booker T. Washington (John Clay III). All these individuals make up the living fabric of America.

At its most revelatory, Ragtime exposes elements of our present as the continuation of entrenched issues never resolved from our past. Despite our great strides in nuclear fission and quantum computing, retrograde darkness still lurks in the nation’s beating heart, in its violence, in its human rights inequities. Clear-eyed, incisive, DeBessonet’s spare choices about spectacle and design, and her focus on great acting and singing by the leads and ensemble, ground this masterwork.

Ragtime begins with an interesting unexplained entrance: a winsome and beautiful Black male child in period dress frolics across a bare stage. At the conclusion the circle comes to a close and he appears again. We discover who he is and what he symbolizes in a stark, crystallizing moment of elucidation. After the opening number (“Ragtime”), Mother’s adventure as head of her household begins when Father leaves (“Goodbye My Love”). Her helpers include her outspoken, prescient, son Edgar (Nick Barrington), her younger brother (Ben Levi Ross), and her opinionated, crotchety father (Tom Nelis).

However, the peace and serenity of their lives become interrupted when Mother discovers an abandoned baby in her garden. After much deliberation, Mother takes in the infant and traumatized mother, Sarah. Clearly, this startling act of redemption never would have occurred if Father was present. As an assertion of Mother’s right to make her own decisions, her grace becomes a turning point in the lives of the baby’s father, Coalhouse, and his love, Sarah. Apparently, Coalhhouse left Sarah to travel for his career, not knowing she was pregnant. He was pursing his dream of being a singer/composer of the new ragtime music.

By he time Coalhouse searches for Sarah to eventually find and woo her back to him, we note the tribulations of Tateh, who tries to survive using his artistic skills (like Harry Houdini). And we note the moguls of a corrupted capitalism, i.e. Ford, Morgan (“Success”), who Emma Goldman accuses of exploitation. They keep the workers and society oppressed and poor.

Using his charm and daily persistence (“he Courtship,” “New Music,”), Coalhouse wins Sarah back. In a dramatic, dynamic moment, Henry’s Coalhouse sings with emotion, “Sarah, come down to me.” When Lewis’ Sarah descends, their fulfillment together is paradise. The stunning scene like the ones that follow, i.e. “New Music,” and especially Henry and Lewis’ “Wheels of a Dream,” where Coalhouse and Sarah sing to their son about America, are hopeful and heartbreaking. Again, the audience stopped the show with applause and cheers as they periodically did throughout the production.

On the wave of Coalhouse and Sarah’s togetherness and love reunited, we forget the underbelly of a dark America that looms around the corner. It does appears during Father’s reunion with Mother after his lengthy voyage.

Unhappily, Father returns to a household in chaos with Sarah, Coalhouse and the baby under his roof. He can’t imagine what “got into” his wife and makes demeaning remarks about the baby. His conservative, un-Christian-like attitude upsets Mother. She defends her position and replies with demure, feminine instruction. Interestingly, her comment indicates she will not heel to him like the good lap dog she was before he left. As with the other leads, Levy’s performance is unforgettable in its specificity, nuance and authenticity.

Clearly, the characters have made inroads with each other bringing socioeconomic classes together during events when activists like Emma Goldman and Booker T. Washington make their mark and reaffirm equality. As a representative of the wave of immigrants coming to America from other teeming shores, Uranowitz’s Tateh steals our hearts and pings our consciences, thanks to his human, loving portrayal. Despite his bitterness in having to brace against the poverty he came to escape, he tries to overcome his circumstances and with ingenuity and pluck continually perseveres. Uranowitz’s Tateh particularly makes us consider the current government’s cruel, unconstitutional response toward migrants and immigrants today.

Act II answers the conflicts presented in Act I, leaving us with a troubling expose of our country’s heart of darkness. Yet, the musical uplifts bright halos of hope with the return of the adorable Black male child. We discover who he is and understand his mythic symbolism. Also, we learn the fate of the characters, some justly deserved. And the audience leaves remembering the cries of “Bravo” that resounded in their ears for this mind-blowing production.

Ragtime

With music direction by James Moore Ragtime runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission through Jan. 4 at the Vivian Beaumont Theater lct.org.

‘A Man of No Importance’ at CSC, a Superb Revival

In its second Off Broadway go-round (Lincoln Center in 2002) Terrence McNally’s book and Stephen Flaherty’s music with Lynn Ahrens’ lyrics of A Man of No Importance directed and designed by John Doyle, is currently at CSC until 18 of December. The production is Doyle’s unaffecting and warm goodbye as Artistic Director of CSC. The uplifting, poignant musical appropriately reminds us of the vitality of theater, whether it be in an office space or a majestic 1500 seat house on 42nd street. Unlike the titular film A Man of No Importance is based on (1994, starring Albert Finney, written by Barry Devlin, produced by Little Bird) live theater is interactive. The audience spurs on the actors in a kinetic, telepathic bond that is incredibly enjoyable once opening night jitters are put to rest.

This most probably is what keeps protagonist Alfie, a DIY theater director of Dublin’s St. Imelda’s Church players inspired and engaged, though their performances are reportedly terrible. And it is why he is wickedly devastated when Father Kenny (Nathaniel Stampley) closes down their production of Salome, because it is inappropriate and untoward for a community church theater show, though the story is right out of scripture. Actually, by the end of the production we learn that the butcher, Mr. Carney (Thom Sesma), who is one of their amateur troupe, complained to Father Kenny that Salome was tantamount to pornography because he had a small role and that pissed him off.

Alfie (portrayed by the likable and heartfelt Jim Parsons) apart from his love and spirit guidance by Oscar Wilde, who encourages him to read poems while at his job as a conductor on a Dublin bus, is a closeted, sensitive gay man. He lives with his domineering sister Lily (the always superb Mare Winningham) in their small apartment, where he keeps a raft of books and tests out his gourmet international recipes on her unadorned, “Irish stew palette.”

The year is 1964 before the cultural revolution, “free love,” mini skirts, The Beatles phenomenon and a relaxation of Catholicism’s strictures that didn’t really happen until decades later. Then, the Republic of Ireland was repressed and oppressed by doctrine that made it look more like the radical, right-wing conservative anti-LGBTQ, anti-abortion, red state swamp areas of the American South in 2022. Because of such cultural dispossession, Alfie lives in a fantasy world of art, theater and poetry. He remains inspired by his spiritual advisor, fellow Irishman Oscar Wilde, as he tries to improve the lives of those around him, whether at his job as a conductor, at home with his sister, or at the church, directing his St. Imelda Players.

When Father Kenny closes down their amateur troupe, Alfie is quite bereft, until the St. Imelda Players decide to perform a play of the events that have brought them to where they are at the finish line in the present (1964) with no winning trophy. But instead of directing them, Alfie will be the star of their play.

Cleverly, McNally, Flaherty and Ahrens adjusted and adapted the film as a flashback sandwiched by the present. The church players become the Greek chorus who engineer the events of the play, streamlining them into the action that happened at St. Imelda’s before Father Kenny shuttered their company. They sing songs that embody the emotional feeling and turning points of those events. These songs include the conflict between and among the characters, personal confessions and revelations, and the positive message that they gain from what they’ve learned together. They introduce Alfie as their star, then perform the tuneful, ironic opening number, “A Man of No Importance,” in celebration of their beloved friend and director who is their hero, integral to all of their lives. We learn by the conclusion of their musical, that to them, he is a man of great significance.

Doyle has staged the musical with an approach to DIY theater, reflective of what the St. Imelda Players might effect. The props are cleverly selected, i.e. a drum is used as the bus steering wheel. The actors use minimal furniture to create the environs where the events occur. Chairs suggest the bus that conductor Alfie is on with the driver, the affable and lively Robbie Fay (A.J. Shively, whose “The Streets of Dublin” rocks it). The players become the bus passengers with a new passenger Adele, the lovely voiced Shereen Ahmed catching the attention of Alfie as he quotes from a poem by his spirit mentor Oscar Wilde. By the end of their ride, The St. Imelda Players complete singing the titular “A Man of No Importance.”

As the players give us a tour of Alfie’s life in Dublin, we drop in on him with sister Lily, who is happy to discover that Alfie has found interest in a woman. She sings”Burden of Life” as an answer to her prayers so that perhaps now Alfie can settle down, and she can be free of taking care of him. Mare Winningham is humorous and vibrant as she takes on the role of Lily. A Catholic woman, she and the others in the troupe miss all the cues that her brother just might not be into women. When this finally comes out later, she reassures him in the song “Tell Me Why” that even though he is gay, she loves him anyway and he should have told her.

Alfie’s interest in Adele is not because her beauty entices him romantically. He thinks she is perfect for the role of Salome. Though she avers and refuses the part initially, Alfie is persuasive and she finally relents. It is his hope to have the handsome Robbie play the part of John the Baptist, perfectly cast to act with Adele. Robbie puts him off and instead invites him to come to the pub (the wonderful “The Streets of Dublin”). Alfie accompanies Robbie and makes a fool of himself singing “Love’s Never Lost” in front of Robbie’s friends. Embarrassed, Alfie leaves, further disturbed at Breton Beret’s (Da’Von T. Moody) interest in him. Additionally, he’s confounded by the “love that dare not speak its name,” a love that he feels for his “Bosie,” as he imagines Robbie to be. (Bosie refers to Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s lover.)

Alfie can only admit this inner conflict as he looks at himself in a mirror encouraged by Oscar Wilde (Thom Sesma). He sings the lyrical “Man in the Mirror” as a way to work through his emotions to achieve self-acceptance. Parsons approaches Alfie’s inner conflict with yearning and honesty, confessing in a dream-state to the persecuted and vilified Oscar Wilde, a man who understands the torment he goes through.

Spurred by her discussion with Mr. Carney about Alfie’s weirdness (“Books”), Carney’s insistence that Salome is pornography, and his pressure to marry, which Lily puts off using Alfie as an excuse, Lily makes an attempt as a matchmaker. She invites Adele home for a meal that Alfie has cooked. Afterward, Alfie walks Adele home and as a friend, he gets her to admit she has “someone.” Her tears suggest that there is a reason her boyfriend is not with her. To reassure her Alfie calms her with another beautiful ballad, “Love Who You Love.” As she leaves, Alfie bumps into Breton Beret who propositions him. Alfie wisely restrains himself. His intuition is correct but his unresolved conflict between his shame at being gay and his longing to find someone to be with is a devastation in a Catholic country where being a homosexual is a mortal sin requiring repentance and conversion. Interestingly, he imagines Oscar Wilde encourages him by suggesting that the only way to remove temptation is by giving in to it.

In Doyle’s production the musical is streamlined to eliminate an intermission and keep it as one continuous series of events that move with swiftness, as players would effect their version of what happened, without including every detail. There are fewer players and most of them are incredible musicians that round out the small band tucked away in a second floor balcony against the back wall of the CSC playing area, where the audience abuts on three sides. Thanks to Bruce Coughlin (orchestrations), Caleb Hoyer (music director) Strange Cranium (electronic music design) the music arrangements, Doyle’s staging and the players’ vocal work is gorgeous, and seamlessly, perfectly wrought in configuring the St. Imelda’s Players’ production. Indeed, they are much better than they’ve jokingly been described.

After the turning point (“Love Who You Love” carries the theme) the players reveal that Adele can’t continue with her lines as Salome because the words convict her soul. She can’t act a role where she’s supposed to be innocent and virginal, because in real life, she’s a fallen woman, who had intercourse out of wedlock and now is pregnant. Full of guilt and remorse her punishment is self-torment and humiliation. She must emotionally suffer the rest of her life because abortion is out of the question and the father won’t marry her to make the baby legitimate. The church and the oppressive paternalistic folkways of the culture vilify her with unworthiness and condemnation.

Catholicism hangs over the heads of the characters like a dirge of annihilation and judgment. Adele will have to go home to receive help from her parents to raise the child. Meanwhile, Mr. Carney also uses religious folkways to shut down the play. To add insult to injury, Robbie feels condemned by Alfie when Alfie unwittingly interrupts Robbie and Mrs. Patrick (Jessica Tyler Wright) making love in the bus garage. Feeling the weight of the sin of adultery, Robbie insults Alfie and judges Alfie’s life is without love, an accusation that torments Alfie because he loves Robbie.

Alfie can never reveal this love to him because it would drive Robbie away. Though Alfie has attempted to confess to Father Kenny (“Confession”) he can’t bring himself to reveal his great sin and thus is damned with guilt. As a result of the conflict of loving someone who would never love him, and being accused by that same person as being unloving, Alfie throws caution to the winds. He engages with Breton Beret who has been waiting for the opportunity to make himself look like a real man by beating up a “poof.”

Clearly, the film (1994) was made at a time when the Catholic church was dealing with its own sexual sins which finally came to the fore in the world wide expose of pederasty in the church around 2002. However, the film/musical sets the events back in the 1960s before any of the cultural revolutions took place. Nevertheless, to understand the full force of Catholicism condemnation of homosexuality, check the numbers of gay men who were abused as Alfie is abused by the likes of Breton Beret, or look at the numbers of Catholic gay men committing suicide because they couldn’t reconcile their feelings with their religion. Also, read up on the Republic of Ireland’s approach toward girls who got pregnant out of wedlock in the book Philomena (also a fabulous film with Judi Dench). Or read the stories of the Magdalene Laundries, captured in the film The Magdalene Sisters. The brutality of the paternalistic Catholic folkways winked at male adultery like Robbie’s and swept it under the rug as “boys will be boys.” As for gays or women with babies born out of wedlock, the humiliation, shame and condemnation was a cruelty that destroyed lives.

In the book of the musical McNally is not heavy handed with Catholicism in its iteration at St. Imelda’s community church. The musical has a light touch and religion appears to take a back seat, if we are not aware of the entrenched history of the church and its devastation on its believers. Rather, it is understated with Robbie’s anger at being discovered by Alfie, and Adele’s tears when the father of her child abandons her after he takes what he wants. Alfie gets the worst of it because he is discovered as a homosexual by the police who come to save him from being beaten to death by Beret. But the rub is he can’t press charges for assault because public opinion against “poofs” is more reprehensible than a physical assault. In fact it is intimated that Beret gets backroom laughs and cheers for beating up a homosexual who fell for his enticement.

McNally, Flaherty and Ahren configure the church’s worst folkways to be the sub rosa driving force for all of the humiliation, self-condemnation and torment that makes the conclusion so incredibly vital to A Man of No Importance. Thanks to Doyle, the performers and the creative team’s talents, the conclusion is uplifting and poignant for us today with a message of love and acceptance that is never old. It is the true spirit of Christmas in this “Happy Holidays” season, and in the United States needs to be proclaimed from the rooftops. In its quiet and unassuming way, A Man of No Importance is a trophy winner.

Kudos to Ann Hould-Ward (costume design), Adam Honore (lighting design) and Sun Hee Kil (sound design) and the entire cast and creative team who bring Doyle’s vision to life. The excellent must-see A Man of No Importance is at CSC until 18 December. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.classicstage.org/current-season/a-man-of-no-importance