Blog Archives

Bobby Cannavale, James Corden, Neil Patrick Harris Are LOL in ‘Art’

Superb acting and humorous, dynamic interplay bring the first revival of Yasmina Reza’s Tony-award winning play Art into renewed focus. The play, translated from the French by Christopher Hampton, is about male friendship, male dominance and affirming self-worth. Directed by Scott Ellis, the comedy with profound philosophical questions about how we ascribe value and importance to items considered “art” as a way of bestowing meaning on our own lives resonates more than ever. Art runs until December 21st at the Music Box Theatre with no intermission.

When Marc (Bobby Cannavale) visits his friend Serge (Neil Patrick Harris) and discovers Serge recently spent $300,000 dollars on a white, modernist painting without discussing it with him, Marc can’t believe it. Though the painting by a known artist in the art world can be resold for more money, Marc labels the work “shit,” not holding back to placate his friend’s ego. The opening salvo has begun and the painting becomes the catalyst for three friends of twenty-five years to reevaluate their identity, meaning and bond with each other.

As a means to reveal each character’s inner thoughts, Reza has them address the audience. Initially Marc introduces the situation about Serge’s painting. After Marc insults Serge’s taste and probity, Serge quietly listens, makes the audience, his confidante and expresses to them what he can’t tell Marc. In fact Serge categorizes Marc’s opinion saying, “He’s one of those new-style intellectuals, who are not only enemies of modernism, but seem to take some sort of incomprehensible pride in running it down.” As Serge attempts to pin down Marc reinforcing Marc’s lack of expertise or knowledge about modern art, he questions what standards Marc uses to ascribe his valuable painting as “this shit.”

At that juncture Reza emphasizes her theme about the arbitrary conditions around assigning value to objects, people, anything. Without consensus related to standards, only experts can judge the worth of art and artifacts. Obviously, Marc doesn’t accept modernist experts or this painter’s work. He asserts his opinion through the force of his personality and friendship with Serge. However, his insult throws their friendship into unknown territory and capsizes the equilibrium they once enjoyed. The power between them clearly shifts. The white canvass has gotten in the way.

During the first thrust and parry between Marc and Serge in their humorous battle of egos, the men resolve little. In fact we learn through their discussions with their mutual friend Yvan (James Corden), they think that each has lost their sense of humor. The purchase of the painting clearly means something monumental in their relationship. But what? And how does Yvan fit into this testing of their friendship?

Marc’s annoyance that Serge purch,ased the painting without his input, becomes obsessive and he seeks out Yvan for validation. First he warns the audience about Yvan’s tolerant, milquetoast nature, a sign to Marc that Yvan doesn’t care about much of anything if he won’t take a position on it. During his visit with Yvan, Marc vents about Serge’s pretensions to be a collector. Though he knows he can’t really manipulate Yvan about Serge because Yvan remains in the middle of every argument, he still tries to influence Yvan against the painting.

Marc believes if Yvan tolerates Serge’s purchase of “shit” for $300,000, then he doesn’t care about Serge. Tying himself in knots, Marc considers what kind of friend wouldn’t concern himself with his friend getting scammed $300,000 for a shit panting? If Yvan isn’t a good friend to Serge, at least Marc shows he cares by telling Serge the painting is “shit.” Without stating it, Marc implies that Serge has been duped to buy a white canvass with invisible color in it he doesn’t see based on BS, modernist clap trap.

In the next humorous scene between Yvan and Serge, knowing what to expect, Yvan sets up Serge, who excitedly shows him the painting. True to Marc’s description of him, Yvan stays on the fence about Serge’s purchase not to offend him. However, when Yvan reports back to Marc about the visit, he disputes Marc’s impression that Serge lost his sense of humor. In that we note that Yvan has no problem upsetting Marc when he says that he and Serge laughed about the painting. However, when Marc tries to get Yvan to criticize Serge’s purchase, Yvan tells him he didn’t “love the painting, but he didn’t hate it either.”

In presenting this absurd situation Reza explores the weaknesses in each of the men, and their ridiculous behavior which centers around whose perception is superior or valid. Additionally, she reveals the balance inherent in friendships which depend upon routine expectations and regularity. In this instance Serge has done the unexpected, which surprises and destabilizes Marc, who then becomes upset that Yvan doesn’t see the import behind Serge’s extreme behavior.

Teasing the audience by incremental degrees prompting LOL audience reactions, Reza brings each of the men to a boiling point and catharsis. Will their friendship survive their extreme reactions (even Yvan’s noncommittal reaction is extreme) and differences of opinion? Will Serge allow Marc to deface what he believes to be “shit” for the sake of their friendship? In what way are these middle-aged men asserting their “place” in the universe with each other, knowing that that place will soon evanesce when Death knocks on their doors?

The humorous dialogue shines with wit and irony. Even more exceptional are the actors who energetically stomp around in the skins of these flawed characters that do remind us of ourselves during times when passion overtakes rationality. Each of the actors holds their own and superbly counteracts the others, or the play would seem lopsided and not land. It mostly does with Ellis’ finely paced direction, ironic tone, and grey walled set design (David Rockwell), that uniformly portrays the similarity among each of the characters’ apartments (with the exception of a different painting in each one).

Reza’s characters become foils for each other when Marc, Serge and Yvan attempt to assert their dominance. Ironically, Yvan establishes his power in victimhood.

Arriving late for their dinner plans, Corden’s Yvan bursts upon the scene expressing his character in full, harried bloom. His frenzied monologue explodes like a pressure cooker and when he finishes, he stops the show. The evening I saw the production, the audience applauded and cheered for almost a minute after watching Corden, his Yvan in histrionics about his two fighting step-mothers, fiance, and father who hold him hostage about parental names on his and his fiance’s wedding invitations. Corden delivers Yvan’s lament at a fever pitch with lightening pacing. Just mind-blowing.

The versatile Neil Patrick Harris portrays Serge’s dermatologist as a reserved, erudite, true friend who “knows when to hold ’em and knows when to fold ’em.” Cannavale portrays Marc’s assertive personality and insidiously sardonic barrel laugh with authenticity. Underneath the macho mask slinks inferiority and neediness. Together this threesome reveals men at the worst of their game, their personal power waning, as they dodge verbal blows and make preemptive strikes that hide a multitude of issues the playwright implies. They are especially unwinning at successful relationships with women.

Reza’s play appears more current than one might imagine. As culture mavens and influencers revel in promoting and buying brands as a sign of cache, the pretensions of superiority owning, for example, a Birkin bag, bring questions about what an item’s true worth is and what that “worth” means in the eye of the beholder. Commercialism is about creating envy and lust and the illusion of value. To what extent do we all fall for being duped? Does Marc truly care that his friend may have fallen for more hype than value? Conclusively, Yvan has his own problems to contend with. How can he move beyond, “I don’t like it, I don’t hate it.”

As for its own value, Art is worthwhile theater to see the performances of these celebrated actors who have fine tuned their portrayals to a perfect pitch. Art runs 1 hour 35 minutes with no intermission through Dec. 21 at the Music Box Theater. artonbroadway.com.

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

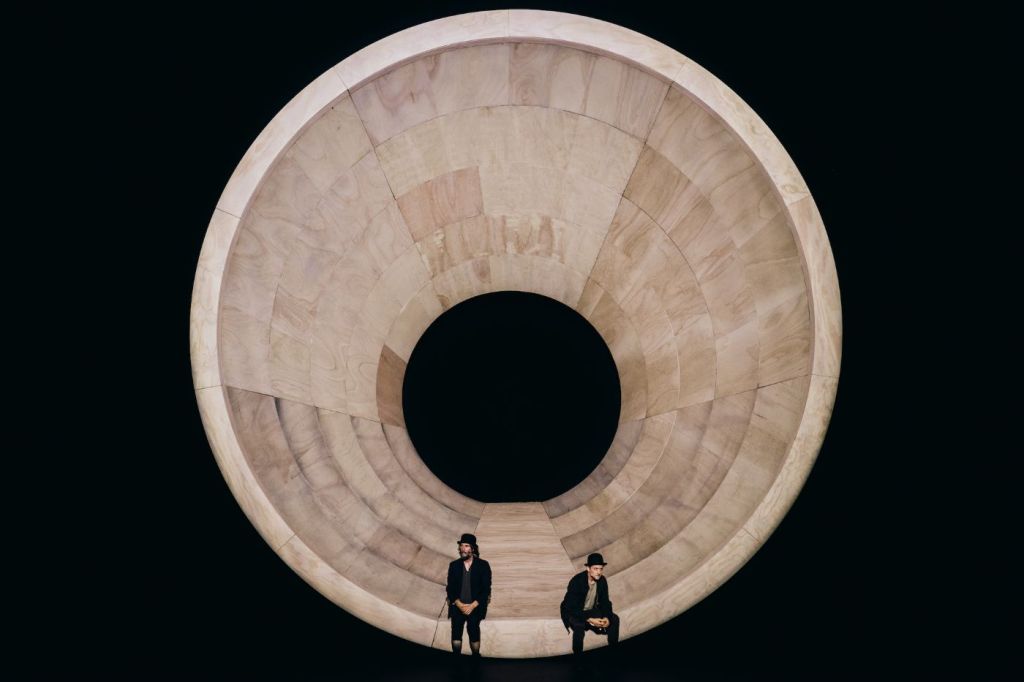

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.

‘Irishtown,’ a Rip-Roaring Farce Starring Kate Burton

Irishtown

In the hilarious, briskly paced Irishtown, written by Ciara Elizabeth Smyth, and directed for maximum laughs by Nicola Murphy Dubey, the audience is treated to the antics of the successful Dublin-based theatre company, Irishtown Plasyers, as they prepare for their upcoming Broadway opening. According to director Nicola Murphy Dubey, the play “deals with the commodification of culture, consent and the growing pains that come with change.”

Irishhtown is also a send up of theatre-making and how “political correctness” constrains it, as it satirizes the sexual relationships that occur without restraint, in spite of it. This LOL production twits itself and raises some vital questions about theater processes. Presented as a world premiere at Irish Repertory Theatre, Irishtown runs until May 25, 2025. Because it is that good, and a must-see, it should receive an extension.

The luminous Kate Burton heads up the cast

Tony and Emmy-nominated Kate Burton heads up the cast as Constance. Burton is luminous and funny as the understated diva, who has years of experience and knows the inside gossip about the play’s director, Poppy (the excellent Angela Reed). Apparently, Poppy was banned from the Royal Shakespeare Company for untoward sexual behavior with actors. Burton, who is smashing throughout, has some of the funniest lines which she delivers in a spot-on, authentic, full throttle performance. She is particularly riotous when Constance takes umbrage with Poppy, who in one instance, addresses the cast as “lads,” trying to corral her actors to “be quiet” and return to the business of writing a play.

What? Since when do actors write their own play days before their New York City debut? Since they have no choice but to soldier on and just do it.

The Irishtown Players become upended by roiling undercurrents among the cast, the playwright, and director. Sexual liaisons have formed. Political correctness didn’t stop the nervous, stressed-out playwright Aisling (the versatile Brenda Meaney), from sexually partnering up with beautiful lead actress Síofra (the excellent Saoirse-Monica Jackson). We learn about this intrigue when Síofra guiltily defends her relationship with the playwright, bragging to Constance about her acting chops. As the actor with the most experience about how these “things” work in the industry, Constance ironically assures Síofra that she obviously is a good actress and was selected for that reason alone and not for her willingness to have an affair with Aisling.

Eventually, the truth clarifies and the situation worsens

Eventually, the whole truth clarifies. The rehearsals become prickly as the actors discuss whether Aisling’s play needs rewrites, something which Quin (the fine Kevin Oliver Lynch), encourages, especially after Aisling says the play’s setting is Hertfordshire. As the tensions increase between Quinn and Aisling over the incongruities of how an Irish play can take place in England, Constance stumbles upon another sexual intrigue when no one is supposed to be in the rehearsal room. Constance witnesses Síofra’s “acting chops,” as she lustily makes out with Poppy. This unwanted complication of Síofra cheating on Aisling eventually explodes into an imbroglio. To save face from Síofra’s betrayal and remove herself from the cast’s issues with the play’s questionable “Irishness,” Aisling quits.

Enraged, the playwright tells Síofra to find other living arrangements. Then, she tells the cast and director she is pulling the play from the performance schedule. This is an acute problem because the producers expect the play to go on in two weeks. The company’s hotel accommodation has been arranged, and they are scheduled to leave on their flight to New York City in one week. They’re screwed. Aisling is not receptive to apologies.

What is in a typical Irish play: dead babies? incest? ghosts?

Ingeniously, the actors try to solve the problem of performing no play by writing their own. Meanwhile, Poppy answers phone calls from American producer McCabe (voice over by Roger Clark). Poppy cheerily strings along McCabe, affirming that Aisling’s play rehearsals are going well. Play? With “stream of consciousness” discussions and a white board to write down their ideas, they attempt to create a play to substitute for Aisling’s, a pure, Irish play, based on all the elements found in Irish plays from time immemorial to the present. As a playwright twitting herself about her own play, Smyth’s concept is riotous.

The actors discover writing an Irish play is easier said than done. They are not playwrights. Regardless of how exceptional a playwright may be, it’s impossible to write a winning play in two days. And there’s another conundrum. Typical Irish plays have no happy endings. Unfortunately, the producers like Aisling’s play because it has a happy ending. What to do?

Perfect Irish storylines

In some of the most hilarious dialogue and direction of the play, we enjoy how Constance, Síofra and Quin devise their “perfect Irish storylines,” beginning with initial stock characters and dialogue, adding costumes and props taken from the back room. Their three attempts allude to other plays they’ve done. One hysterical attempt uses the flour scene from Dancing at Lughnasa. Each attempt turns into funny scenes that are near parodies of moments in the plays referenced. However, they fail because in one particular aspect, their plots touch upon the subject of Aisling’s play. This could result in an accusation of plagiarism. But without a play, they will have to renege on the contract they signed, leaving them liable to refund the advance of $250,000.

As their problems augment, the wild-eyed Aisling returns to attempt violence and revenge. During the chaotic upheaval, a mystery becomes exposed that explains the antipathy and rivalry between Quin and Aisling. The revelation is ironic, and surprising with an exceptional twist.

Irishtown is not to be missed

Irishtown is a breath of fresh air with laughs galore. It reveals the other side of theater, and shows how producing original, new work is “darn difficult,” especially when commercial risks must be borne with a grin and a grimace. As director Nicola Murphy Dubey suggests, “Creative processes can be fragile spaces.” With humor the playwright champions this concept throughout her funny, dark, ironic comedy that also is profound.

Kudos to the cracker-jack ensemble work of the actors. Praise goes to the creatives Colm McNally (scenic & lighting design), Orla Long (costume design), Caroline Eng (sound design).

Irishtown runs 90 minutes with no intermission at Irish Repertory Theatre, 132 West 22nd St. It closes May 25, 2025. https://irishrep.org/tickets/

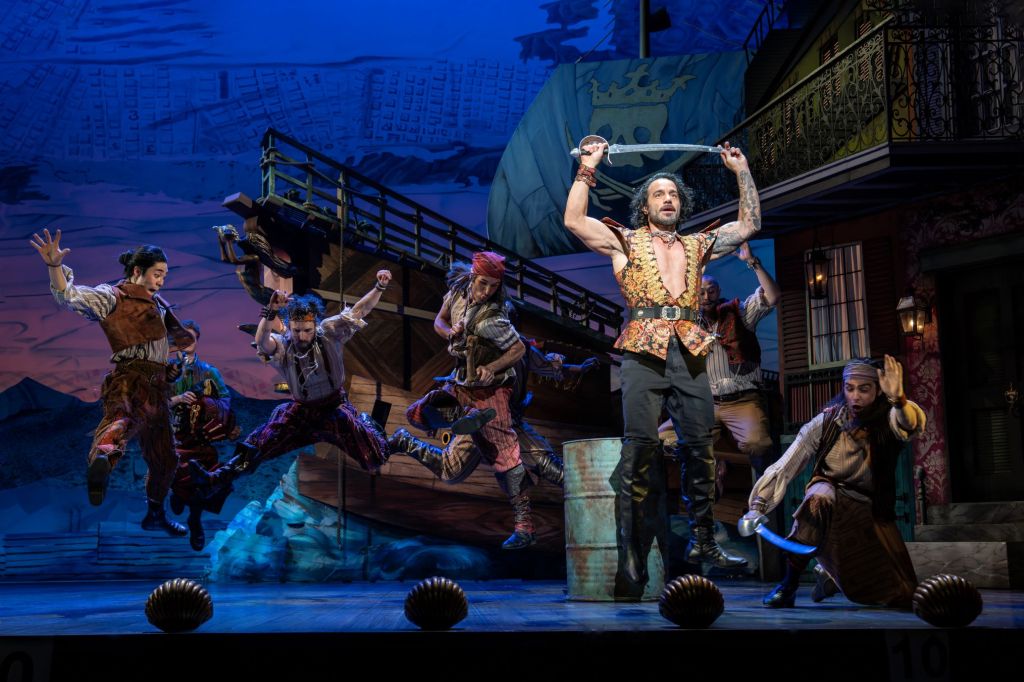

‘Sunset Blvd.’ A Thrilling, Edgy, Mega Spectacle, Starring Nicole Scherzinger

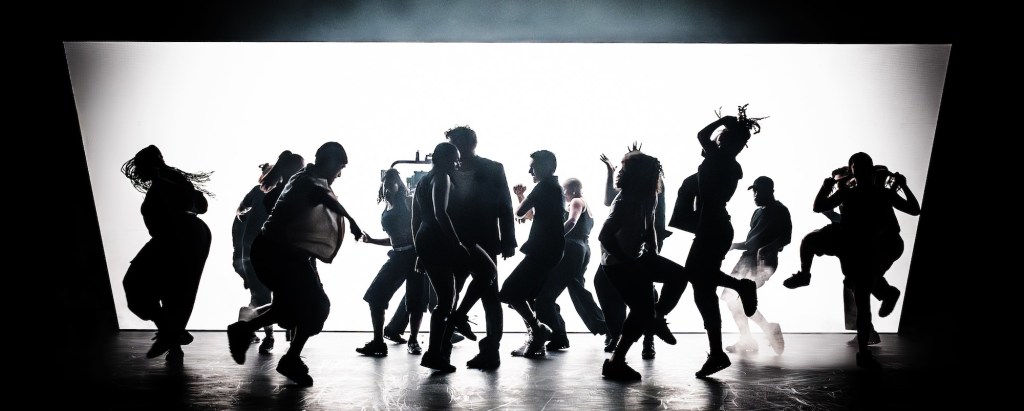

If you have seen A Doll’s House with Jessica Chastain, Cyrano de Bergerac with James McAvoy or Betrayal with Tom Hiddleston, you know that director Jamie Lloyd’s dramatic approach reimagining the classics is to present an unencumbered stage and few or no props. The reason is paramount. He focuses his vision on the actors’ characters, and their steely, maverick interpretation of the playwright’s dialogue. The actors and dialogue are the theatricality of the drama. Why include extraneous distractions? Using this elusively spare almost spiritual approach which is archetypal and happens in what appears to be pure, electrified consciousness, Lloyd is a throwback to ancient Greek theater, which used few if any sets. As such Lloyd’s reimagining of the magnificently performed, uncluttered, cinematically live spectacle, Sunset Blvd., currently at the St. James Theatre in its second Broadway revival, is a marvel to behold.

The original production, with music by Andrew Lloyd Webber and book and lyrics by Don Black and Christoper Hampton, opened in 1993. Lloyd’s reimagining configures the musical on a predominately black “box” stage that appears cavernous. Soutra Gilmour’s black costumes (with white accessories, belts, Joe’s T-shirt), are carried through to the black backdrop whose projection, at times, is white light against which the actors/dancers gyrate and dance as shadow figures. The white mists and clouds of fog ethereally appear white in contrast to the background. There is one stark exception of blinding color (no spoiler, sorry), toward the last scene of the musical.

As a result, David Cullen and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s orchestrations under Alan Williams’ music supervision/direction sonorously played by the 19 piece orchestra are a standout. The gorgeous, memorable music is a character in itself, one of the points of Lloyd’s stunning production. From the overture to the heightened conclusion, the music carries tragedy lushly, operatically in a fascinating accompaniment/contrast to Lloyd’s spare, highly stylized rendering. On stage there are just the actors, their figures, voices and looming faces, which shine or spook shadows, sinister in the dim light. The immense faces of the main four characters in black and white, like the silent film stars, gleam or horrify. The surreal, hallucinatory effect even abides when the actors/dancers stand in the spotlights, or the towers of LED lights, or huddle in a dance circle as the cinematographer films close-ups thanks to Nathan Amzi & Joe Ransom.

The symbolism of the staging and selection of colors is open to many interpretations, including a ghostly haunting of the of the Hollywood era, which still impacts us today, persisting with some of the most duplicitous values, memes, behaviors and abuses. These are connected to the billion dollar weight loss industry, the medical (surgery and big pharma) industry, the fashion and cosmetics industry, and more. The noxious values referenced include ageism, appearance fascism (unreal concepts of beauty and fashion for women that promote pain, chemical dependence and prejudice), voracious, self-annihilating ambitions, sexual youth exploitation, sexual predation and much more. Lloyd’s stark and austere iteration of Sunset Blvd. promotes such themes that the dazzling full bore set design, etc., drains of meaning via distraction and misdirection.

The narrative is the same. Down and out studio writer Joe Gillis (the exceptional, winsome, authentic Tom Francis), to avoid goons sent to repossess his car, escapes onto the grounds of a dilapidated mansion on the famed Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. In the driveway, manservant Max (an incredible David Thaxton), mistakes him for someone else and invites him inside. There, Joe meets Norma Desmond (the divine hellion Nicole Scherzinger), a faded icon of the silent screen era in the throes of mania. Norma is “lovingly,” stoked by Max into the delusion that thousands of fans want her to return to her glory days in a new film.

When Norma hears Joe is a screenwriter, like a spider with a fly, she traps him to finish her “come-back” film (she wrote the screenplay). Thus, for champagne, caviar and the thrill of it, he stays, lured by the promise of money, the glamour of old Hollywood and the avoidance of debt collectors. As Norma grows dependent on Joe as her gigolo, he ends up falling for the lovely, unadulterated Betty (the fine, sweet, Grace Hodgett Young). Behind Norma’s back, Joe and Betty collaborate on a script and fall in love. The lies and romance end with the tragic truth.

The seemingly empty stage, tower of lights, spotlights for Norma and live streaming camera closeups projected on the back wall screen, Lloyd is the antithesis of the average director, whose vision focuses on lustrous set design and elaborate costumes and props. In Lloyd’s consciousness-raising universe such gaudy commercialism gaslights away from revealing anything novel or intriguing in the meat of this play’s themes or characterizations, which ultimately excoriate the culture with social commentary.

Soutra Gilmour’s set design and related costumes unmistakenly lay bare the narcissism and twisted values the entertainment industry promotes so that we see the destructive results in the interplay between Max, the indulged Norma and the hapless victim Joe, who tries a scam of his own which fails. Ultimately, all is psychosis, illusions and broken dreams turned into black hallucinations. For a parallel, current example, think of an indulged politician who wears bad make-up that under hot lights makes his face melt like Silly Putty. Again, hallucinations, psychosis, narcissism, egotism that is dangerous and ravenous and never satisfied. Such is the stuff insufferable divas are made of.

In the portrayal of the former Hollywood icon who has faded from the public spotlight and become a recluse, in scene three, when Lloyd presents Gillis meeting Desmond, she is the schizoid goddess and Gorgon radiating her own sunlight via Jack Knowles’ powerful, gleaming spotlights and shimmering lighting design, the only “being” worth looking at against the black background. Throughout, Norma possesses the cavernous space of the stage in surround-view black with white mists jetting out from stage left or right, forming symbolic clouds and fog representing her imagined “divinity” and her confused, fogged-over, abject psychotic hallucinations.

Whenever she “brings forth” from her consciousness “on high,” and empowers her fantasies in song, Lloyd has Knowles bathe her lovingly in a vibrant spotlight. When she emerges from the depths of her bleak mansion of sorrows to sing, “Surrender,” “With One Look,” and later, “As if We Never Said Goodbye,” she brings down the house with a standing ovation. Indeed, Norma Desmond is an immortal. She worships her imagined self at her alter of tribute. Her mammoth consciousness and ethos which Max (Thaxton’s incredible, equally magnificent, hollow-eyed, ghoulish, former husband and current director/keeper of her flaming divinity), perpetuates is key in the tragedy that is her life.

Importantly, Lloyd’s maverick, spare, stripped down approach gives the actors free reign to dig out the core of their characters and materialize their truth. In this musical, the black “empty” stage allows Scherzinger’s Norma to be the primal, raging diva who “will not surrender” to oblivion and death. She is a a god. Like the Gorgon Medusa, she will kill you as soon as look at you. And don’t anyone tell her the truth that she is a “has been.”

Of course, Joe does this out of a kindness that she refuses to accept. Without the black and white design, and cinematic streaming, a nod to the silent screen, which allows us to focus on faces, performances, magnified gestures and looks, the meanings become unremarkable. The theme-those who speak the truth must die/be killed because the deluded psychotic can’t hear truth-gains preeminence and Lloyd’s archetypal production gives witness to its timelessness. In her most unnuanced form, Norma is a dictator who must be obeyed and worshiped. Such narcissistic sociopaths must be pampered with lies.

Thus, in the last scene, Scherzinger’s Norma stands in bloody regalia as the spiritual devourer who has just annihilated reality and punished Joe. She is permissively allowed to do so by Max, who like a director, encourages her to star in her own tragedy, as he destroys her and himself. As Joe narrates in the flashback from beyond the grave, he expiates his soul’s mistakes with his cleansing confession, as he emphasizes a timeless object lesson.

From a theatrical perspective, the dramatic tension and forward momentum lies with Lloyd’s astute, profound shepherding of the actors in an illusory space. This becomes a fluid field which can shift flexibly each night, revealed when Joe, et. al run in circles and criss-cross the stage wildly. Expressionistic haunting, the foggy mists, the surrounding black stage walls, black costumes, the barefoot diva-hungrily filling up the spotlight-the shadowy figures, all suggest floating cultural nightmares. These the brainwashing “entertainment” industry for decades forces upon its fans to consume their waking moments with fear, the fear of aging, fear of failure, fear of destitution, fear of not being loved, fear of being alone. Many of these fears are conveyed in the songs, and dance numbers in Fabian Aloise’s choreography.

And yet, when the protagonist takes control of the black space of the stage around her, we understand how this happens. She is mesmerizing, hypnotic. Seduced by what we perceive is gorgeousness, we don’t see the terror, panic and mania beneath the shining surface. Instead, we are drawn as if she indomitably, courageously stands at the edge of the universe and asserts her being. In all of her growing insanity, we admire her persistence in driving toward her desire to be remembered and worshiped. Though it may not be in the medium she wishes, her provocations and Max’s love and loyalty help her achieve this dream, albeit, an infamous one, by the conclusion, as gory and macabre as Lloyd ironically makes it. Indeed, by the end her hallucination devours her.

Sunset Blvd is a sardonic send up of old Hollywood’s pernicious cruelty and savagery in how it ground up its employees (“Let’s Have Lunch,” Aloise’s brilliant factory town, conveyor belt choreography, referencing the cynical deadening of Joe’s dreams), and how it made its movie star icons into caricatures that bound their souls in cages of time and youth. Also, it is a drop down into tropes of cinema today in its penchant for horror, psychosis and the macabre, represented by Lloyd’s phenomenal creative team which elucidates this in the color scheme, mists, and starkly hyper-drive, electric atmosphere and movement.

Finally, in one of the most engaging, and exuberantly ironic segments filmed live, right before Act II, when Joe sings Sunset Blvd. with wry, humorous majesty, Tom Francis merges the character with himself as a Broadway/entertainment industry actor. During a live-recorded journey unveiling backstage “reality,” Francis/Joe moves downstairs, inside the bowels of the theater and in the actors’ spaces, so we see the actors’ view, from the stairwell to dressing rooms. Then Francis moves out onto 44th Street, joined by the chorus to eventually move back inside the theater and on stage where they finish singing “Sunset Blvd,” in a thematic parallel of Broadway and Hollywood. Broadway with its wicked inclination to sacrifice art for dollars, truth for commercialism with insane ticket prices, is the same if not worse than Hollywood, until now with AI fueling Amazon, Apple, Google, etc.

However, Broadway came first and spawned the movie industry, which poached actors from “the great white way.” Lloyd clearly makes the connection that the self-destructive dangers of the entertainment industry are the same, whether stage, screen, TV or Tik Tok. The competing themes are fascinating and the lightening strike into the “reality of backstage theater,” refreshes with funny split-second vignettes. For example, Francis peeks into Thaxton’s dressing room. Humorously merging with his character Max, Thaxton ogles a photo of the Pussycat Dolls taped to his mirror. Scherzinger was a former member of the global, best-selling music group (The Pussycat Dolls).

As Lloyd’s most expressionistic pared down, superbly technical extravaganza to date, every thrilling moment holds dynamic feeling, sharply illustrated for maximum impact. As an apotheosis of rage when her gigolo lover speaks the truth that dare not be spoken, Scherzinger’s Desmond becomes primal, a banshee, a Gorgon, a Medea who “refuses to surrender” to the idea that Hollywood, a treasured lover, like Jason, abandoned her for new goddesses.

With cosmic rage Scherzinger releases every, living, fiery nerve of vengeance to destroy the who and what that she can never believe. Meanwhile, Max, her evil twin, with clever prestidigitation, in one final act of loyalty to protect her febrile, mad, entangled imagination, has her get ready for the cameras and close-up, despite Joe’s tell-tale gore on her “black slip,” face and hands, which the media can feed off of like flies. No matter, she sucks up all the spotlight hungrily, clueless she will share a solitary room in a padded sell with no one in a prison for the mentally insane. Perhaps.

This revival should not be missed. Sunset Blvd. with one intermission, two hours 35 minutes is at the St. James Theatre until March 22, 2025 https://sunsetblvdbroadway.com/?gad_source=1