Blog Archives

‘Orpheus Descending,’ One of Tennessee Williams Most Incisive Works-a Searing Triumph

The hell of the South abides in Erica Schmidt’s revival of Orpheus Descending, currently running at Theatre for a New Audience in Brooklyn until August 6th. Tennessee Williams’ poetically brazen work about the underbelly of America that reeks of discrimination, violence, bigotry and cruelty seems particularly regressive in the townspeople of the rural, small, southern, backwater of Two River County, the setting Williams draws for his play.

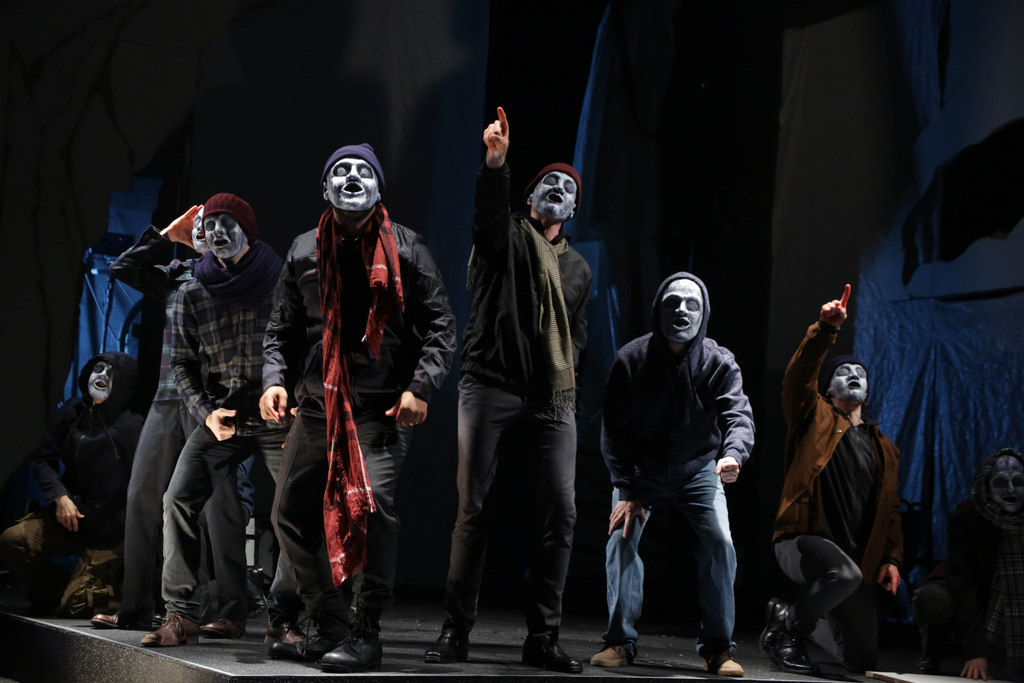

This production is raw in its ferocity, terrifying in its prescience. It reminds us of the extent to which racists and bigots go feeling self-righteous about their loathsome behaviors when the culture empowers them. The director shepherds the actors to give authentic portrayals that remind us that death lurks in the sadistic wicked who seek to devour those whom they may, especially when their targets have peace and happiness, and step over the line (what the bigots hypocritically think is the line).

At the top of the play, we immediately note that stupidity and hypocrisy exude from the pours of most of the homely white characters. Sheriff Talbot and the wealthy Cutrere family are the chief representatives and purveyors of white supremacist, conservative law and order, which is as natural and welcome as white on rice.

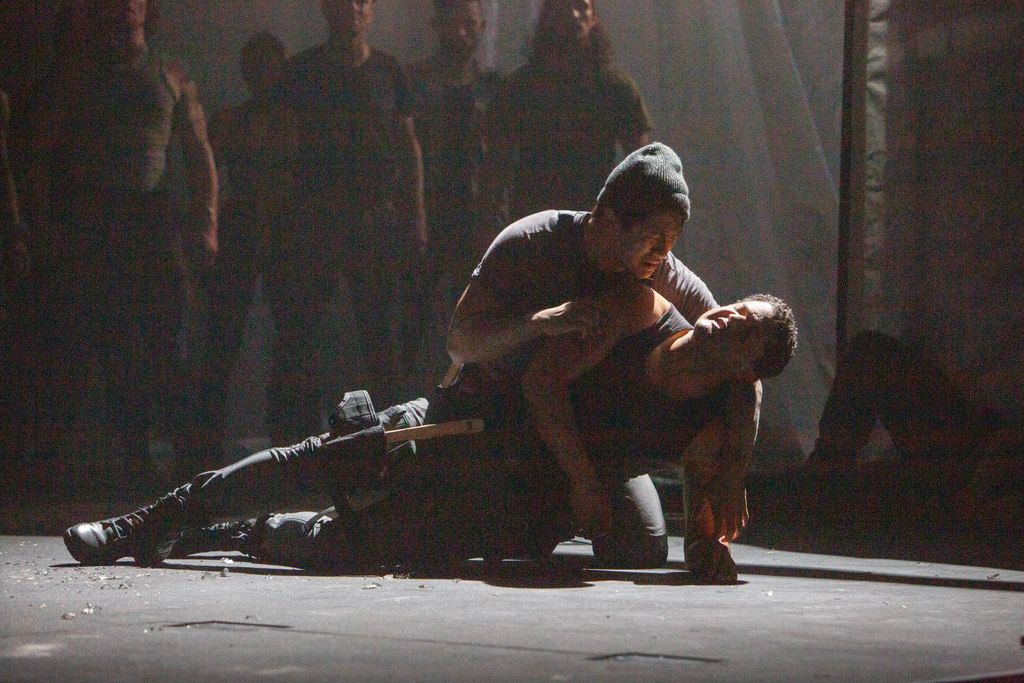

Williams’ brilliant but lesser known work is based on the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. However, Williams updates the allusion and spins it into metaphoric gold transposing the heroic characters into artists, visionaries and fugitives, who rise wildly above the droll deadness of their environs or are delivered from them, as is Lady (Maggie Siff) who is brought to life during her relationship with Val (Pico Alexander). During the course of Val’s and Lady’s dynamic relationship with each other, they seek to cleanse and overcome their past heartbreaks and regrets and move upward toward redemption, reclamation and new beginnings with each other’s help.

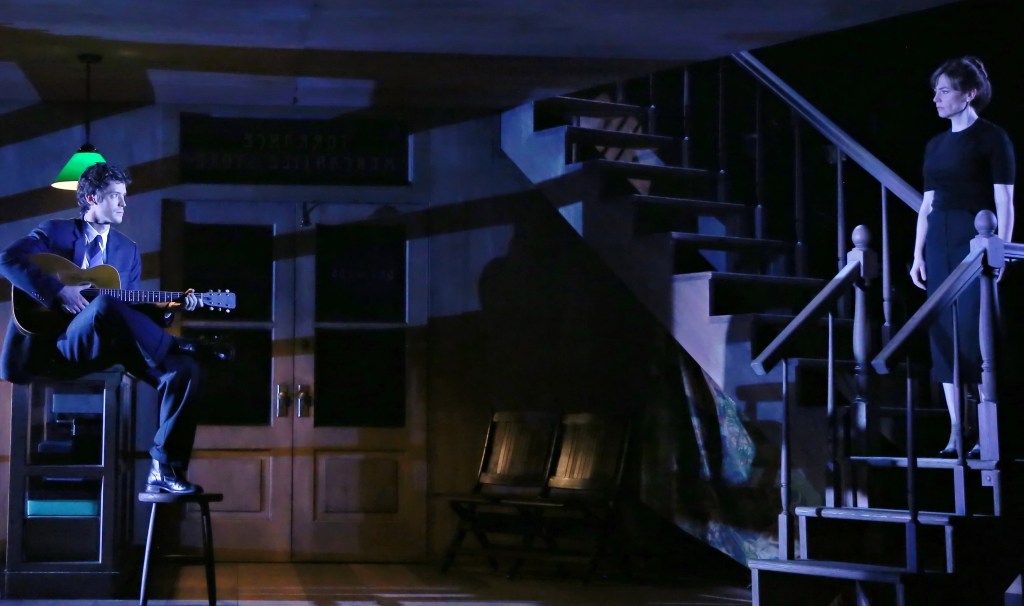

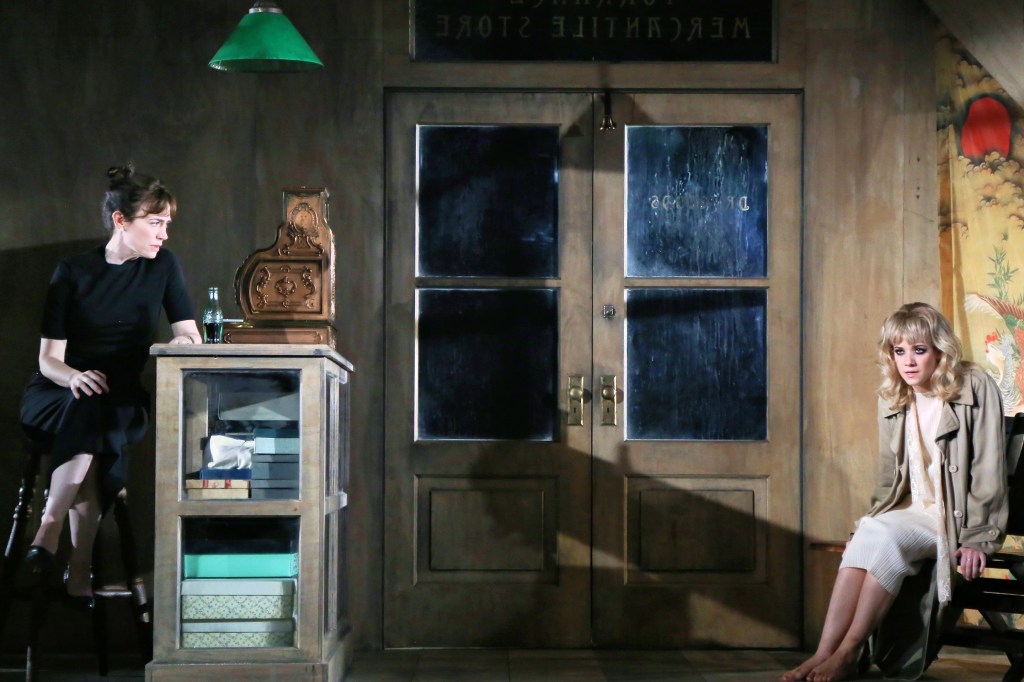

The banal atmosphere conveyed by Amy Rubin’s spare, angular, cage-like design of the Torrence dry goods store is an appropriate setting where most of the conflict and interplay among the characters takes place. Its ugly, hackneyed blandness, lack of vibrancy and straight-edged corners symbolize Lady Torrence’s desolate life with the hypocritical, vapid townspeople and her infirm, brutal, racist, hoary-looking husband Jabe Torrance (the irascible, excellent Michael Cullen).

The other two sections of the set, the confectionery (stage left) and the storage area behind the curtain (stage right), Rubin suggests with minimalism. The confectionery and the storage area symbolize the other aspects of Lady’s character that are not governed by Jabe and the destructive, deadening, Southern folkways. The confectionery eventually outfitted with lanterns symbolizes her hope for renewal and reclamation. The intimate, barely lit, storage area where Val sleeps symbolizes the fulfillment of her desire for love.

Center stage is the store and above it the Torrence bedroom, both subscribed by walls which pen Lady in. Along with Jabe, the store’s visitors suck her life-blood dry with the exception of Val and Vee (Anna Reeder), a Cassandra-like character. Above the store, Jabe lies in bed dying. Empty of kind words, Jabe communicates his bile and bitterness by pounding his cane on the floor from his sick bed. It is an ominous foreboding alarm that one imagines the master sends to his slave when he commands something from them immediately.

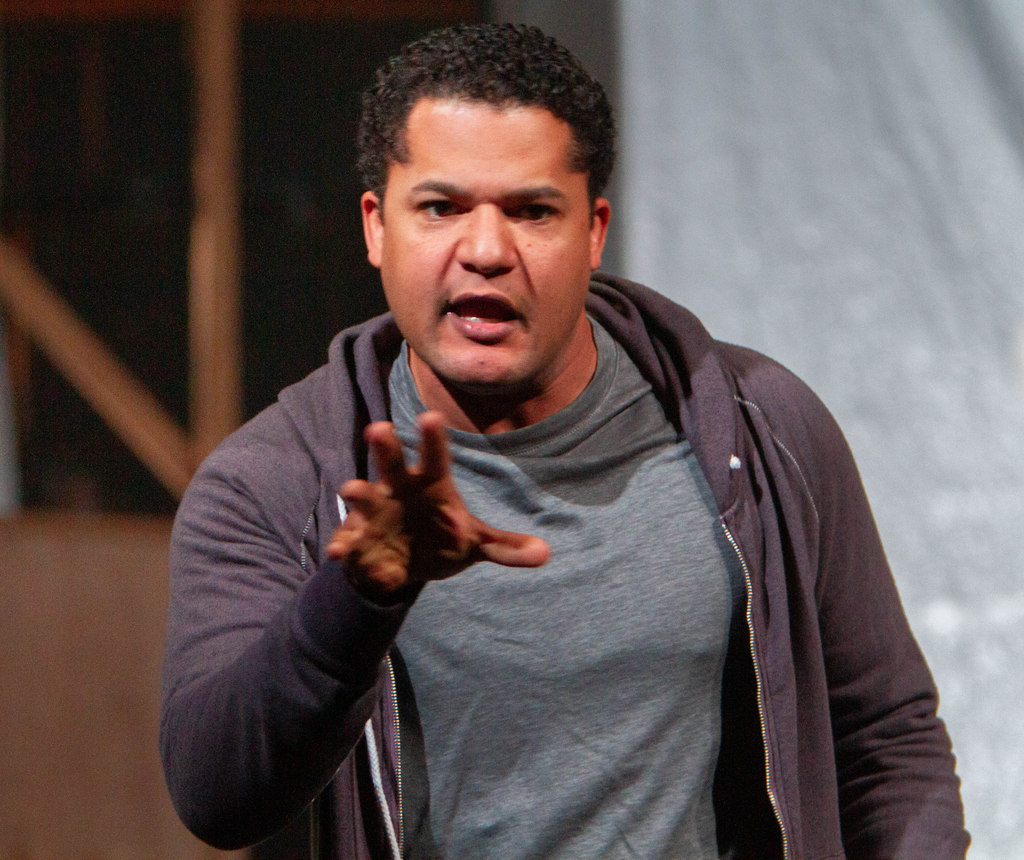

Into Two River county’s washed-out “neon,” “low-life” mediocrity comes the contrasting light and beauty of the guitar artist/entertainer, the stunning and untouchable Val Xavier. Pico Alexander makes the role his own, portraying Val with grace and alluring, angelic innocence befitting “Boy,” the nickname the assertive, feisty Lady gives him. Siff is sterling and likable as she grows vivacious as their bond develops. Siff’s scene where she reveals she is committed to loving Val, despite not wanting to admit needing him is just smashing.

Val illuminates the spaces he enters and shatters the peace of Dolly Hamma (Molly Kate Babos) and Beulah Binnings (Laura Heisler) when he drops by the Torrence store on Vee Talbott’s suggestion that Lady Torrence might give him a job. As he waits patiently for Jabe and Lady to arrive from the hospital after Jabe’s unsuccessful operation, Jabe’s cousins Dolly and Beulah “eye him” while they prepare a celebration for Jabe’s return.

Vee (the fine Ana Reeder), a spiritual visionary born with second sight, accompanies Val and introduces him to the other women hanging around, one of whom is Carol Cutrere (the superb Julia McDermott), a rebellious hellion whose outsized antics and screaming of the Chocktaw cry with Uncle Pleasant, the conjure man (Dathan B. Williams), make the other women apoplectic. Clearly, Carol is an outsider like Val and Lady, only saved by her last name.

As Vee relates the visions that form the basis of the painting she brings for Jabe to encourage his healing, we note she doesn’t fit in either. If she weren’t married to Sheriff Talbott (Brian Keane) her eccentric ways would banish her from the “polite society” gathered in the store, rounded off by gossip mongers, Sister Temple (Prudence Wright Holmes) and Eva Temple (Kate Skinner), who sneak up the wooden steps to check out Jabe’s bedroom before he and Lady return.

Schmidt stages these opening scenes of William’s claustrophobic setting and characters to maximum effect, clustering the women at the counter and bringing Carol and Uncle Pleasant downstage for their chant and evocation. Downstage is where Carol cavorts, delivers a few soliloquies, and wails her outrage and sorrow as an encomium at the play’s conclusion.

By the time Jabe and Lady arrive and Jabe retires upstairs, we have an understanding of the desolate elements and competing life forces that will drive the conflict forward. Additionally, Williams has the gossips share Lady’s terrible backstory that involves the KKK torching her father’s wine garden, and his gruesome death burning alive in the conflagration because not one firetruck or patron came to his aide.

All this was because he violated the towns’ mores and unwritten law serving wine to “ni$$ers. Implied by Jabe later in the play, the “Wop” had too much life in him and had to be cut down to size and made destitute. Interestingly, Lady’s determined father decided he’d rather burn alive trying to salvage his life’s work than accept poverty and brutality in a death-filled culture. For Lady, the acorn doesn’t fall far from the oak. She decides to take a stand against Jabe and his sadistic brutality than run away with Val.

Alexander’s Val and Siff’s Lady establish their relationship gradually with Siff aggressively taunting Val’s appeal to women, one of whom is McDermott’s live-wire Carol. As their comfort level with each other grows, the two bond over Val’s description of a bird that is so free it never corrupts itself by touching the ground and only does so when it dies. Lady expresses her desire for such freedom, and after their discussion is abruptly interrupted by Jabe’s pounding, we note a greater lightheartedness within Lady. Val’s presence is the freedom and wildness that she craves.

Indeed, we note her mood is uplifted every time Lady has a quiet conversation with Val. The actors have the privilege of organically inhabiting these memorable characters with ease to deliver some of the most figuratively elegant and coherently rich dialogue found in all of Williams’ works. One of their most powerful scenes concerns Val’s description of the corrupt world and his own corruption. He counters it by sharing how his “life’s companion,” his guitar and his music, cleanses his impurity and makes him whole again.

As Val settles in and she begins to rely on him, we realize that her inspiration and actions to reopen the confectionery (Schmidt use of the lanterns descending in the stylized space, stage left) run parallel to Val’s regenerative influence over her. He has ignited her hope and desire to be resurrected from the ashes of the burning, the town’s hatred and racism, and Jabe’s enslavement and ownership of her mental and emotional well being.

In his characterization of Jabe, Williams reveals the psychosis of the Southern Red Neck confederates turned white supremacists that lost the Civil War but persist in acting as if they won it, especially with regard to their racism and hatred of Blacks and “the other,” (immigrants). In Schmidt’s version, we see that Jabe’s attitudes and the attitudes of the other men presciently foreshadow the current MAGA Republicans’ penchant to be brutal and criminally sadistic because their “power” gives them the right, regardless of the truth of the circumstance or the legality. Certainly, Jabe has the power and white supremacist friends (Sheriff Talbot) to back up his actions with impunity.

Thus, as Lady has told Val, she “lives” with Jabe, a figure of death who makes sure to stomp down her happiness or agency every chance he gets. In fact each time Val and Lady seek each other’s company for verbal comfort, Jabe almost intuits that she is uplifted away from his presence and claws and pounds (with his cane) his way back into her mind and emotions with his demands. She always goes running to him, for in her soul, she feels she has no other options.

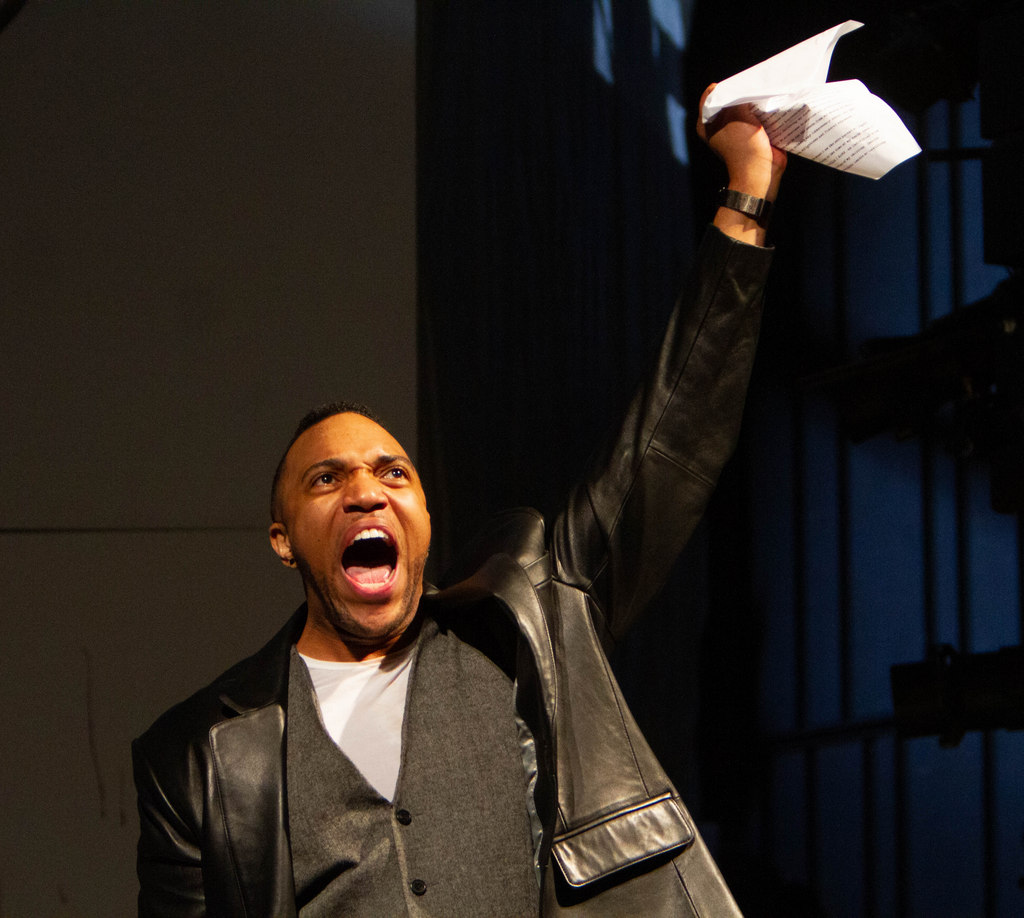

The turning point arrives when Jabe comes downstairs to exert himself over the cancer that is killing him and perpetrate some new malignity against her, which appears to be the only pleasure he has. His emotions are pinged to remembrance when he views the loveliness of the confectionery and the new life that has inspired it (Val). It is then he strikes at Lady provoking her past reason, a white supremacist sadist to the last.

There are no spoilers. What transpires is Williams’ reaffirmation of the modern day tragedy that resulted daily in the Jim Crow South when white supremacists asserted they won the Civil War with every Black person they lynched using law enforcement to cover for them. In the play Williams also infers how this happens in the inhuman, abusive prison system which prompts men to escape and uses the escape as the justification for their killing.

Schmidt and her team have created a production that is bold in revealing Williams’ trenchant themes about death, life, hatred, bigotry, racism and the utter wicked sadism and evil that would keep such a culture going even if the culprits, like Jabe, suffer and are eaten alive by their own hatred. In revealing Williams’ prescient themes that apply for us today, we note that a racist culture cannot be confronted when the power is held by the racists and bigots. Indeed, one must escape the purveyors of death and leave their sphere of influence, if there is no federal oversight or punishment for law breaking. If there isn’t accountability, the individuals, will do as they please, and like despots bend their underlings to their will as death dealers.

Kudos to the creative team which includes Jennifer Moeller’s costume design, David Weiner’s lighting design, Cookie Jordan’s hair and wig design and Justin Ellington’s original music and sound design.

The production concludes August 6th. Don’t miss it for its profound characterizations beautifully acted, acute ideas Schmidt suggests with her fine direction and the technical production values that bring Williams’ stark truths to bear on us today. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.tfana.org/visit/ticket-venue-policies

‘Des Moines,’ the Opaque and Mysterious Artfully Shine at TFANA

In Des Moines by award winning writer Denis Johnson nothing vital seems to happen during the time Dan, his wife Marta, their grandson Jimmy, Father Michael and Mrs. Drinkwater get smashing drunk and have a wild party in Dan and Marta’s modest second floor apartment in Des Moines, Iowa. Yet, in the 12 hours they spend together, much does happen. Connections are made, personal revelations are expressed and in each individual’s life, as a result of the dynamic interactions that take place, all experience a shift. For some it’s in perspective. For others the change is behavioral. However, in this deceptively “small” but mighty play, Johnson reveals the importance of listening to others’ faint soul cries and helping them relax into a zaniness that soothes.

At the play’s outset for a moment all is blackness. We hear a deafening roar, a loud cacophony of noise, a piercing, grating, rolling thunderous sound like a ripping away of the earth’s atmosphere as if a bomb had been dropped. We ask what is happening and what does that sound mean?

The lights come up on cab driver, husband Dan who has come home from work. He hits upon what the sound might be as he discusses with wife Marta that Mrs. Drinkwater, the wife of a man who died in a recent plane crash, has sought him out to ask him questions. Dan was one of the last people to speak to Mr. Drinkwater, when he took him to the airport, before he got in the plane that crashed in an embankment, killing everyone onboard. Thus, we put together the roaring sound at the top of the play with the plane engines roaring before the crash.

By the end of the play we are no closer to understanding the symbolism, though it is repeated during a blackout between scenes after a raucous party. Perhaps it symbolizes the “veil being rent,” what must happen in human consciousness to allow enlightenment and an awakening to flood the psyche with new understanding. Though Johnson makes references to being awakened and made aware, these concepts are fleeting, and unexplained.

This is one of the joys of Des Moines in which Johnson seems to suggest that human existence in its greatest depth is about understanding, empathy and the bridge of consciousness between and among people in the realms of their own experience. All of these elements at one point or another Johnson touches upon in each of his characterizations, portrayed by prodigious actors, who are incisively directed by Arin Arbus.

During Dan’s discussion with Marta, we understand that he is startled that Mrs. Drinkwater would seek him out to ask him questions about her dead husband. It is as if she looks for anything to bring her comfort through the trauma she’s experiencing from her partner’s strange death in a shocking, rare accident. During Dan’s discussion, the playwright raises questions about the fragility of life and the permanence of death. The conundrum of dying in life daily, momentarily looms, then vaporizes as Dan jumps to raw reality. He tells Marta how medical examiners attempt to identify the smashed bodies picked up at the crash site. From what he’s learned from Mrs. Drinkwater, the next of kin are asked to think about looking for one identifying feature of their loved one and not look at or imagine the entire body. Immediately, one’s loved one is reduced to one feature to better help the coroners during the cold and alienating identification process. This is another startling crash of death’s finality which shakes Dan.

Arliss Howard who portrays Dan with an organic realism and authenticity relays Dan’s concern about Mrs. Drinkwater. She is Black and Mr. Drinkwater was a prominent Black lawyer. Seeking information, Mrs. Drinkwater has shown up at the car garage daily to joggle Dan’s memory until he finally pictures her husband and remembers snatches of conversation they had in the cab before Dan dropped him off at the airport. Thus, an ancillary, “meaningless” conversation carries with it great moment for Mrs. Drinkwater and for Dan in light of the catastrophe of Mr. Drinkwater’s irrational and sudden death. Indeed, we are reminded if it happened to him, death will happen to us. Momento mori. Mortality is a hard fact Dan nor Mrs. Drinkwater can’t seem to negotiate, nor can Marta as we discover in her interaction with Father Michael when the priest visits.

Johanna Day as Marta is perfect as Dan’s patient, dutiful partner, who listens to Dan’s concern and gets the importance of this last conversation with the husband. Also, it isn’t unusual to her that Mrs. Drinkwater wants to know everything Dan can remember. We learn later that Dan and Marta, too, have suffered a sudden loss of a loved one. Thus, Mrs. Drinkwater’s endless questioning makes weird sense and reveals the pain and hurt she obviously experiences. It is a shared hurt for Dan and Marta, which we note later in Marta’s fleeting few words which vaporize into thin air, not belabored because the pain of loss has settled into the characters’ ethos, becoming a part of their consciousness.

From their interchange in the kitchen, we note that Dan’s and Marta’s is a close relationship. This closeness bears up throughout the play. They appear to be a typical, married, older couple who have lived together for years. However, on closer inspection, there is nothing typical about them. There is a profound comfort to their relationship that reveals a tight bond that connects them beyond understanding. This closeness especially manifests in their drinking, carousing, acceptance and love of their transgender grandson, who lives with them and who is wheelchair bound. They are also bonded together having experienced pain, loss and tragedy.

The character dynamics take off when Father Michael (the superb Michael Shannon) visits. Denis Johnson has set up Father’s Michael character by having Dan discuss with Marta that he saw Father Michael wearing make-up in front of a gay bar. Ironically, Dan mentions that he won’t feel so inferior or insecure at Confession knowing that Father Michael is less than perfect and most probably is gay. His response is all about forgiveness and an absence of judgment. And it is clear that this has now become a two way street of forgiveness and acceptance.

Marta has asked Father Michael to come over to receive comfort and perhaps prayer as she tells Dan that the doctors only gave her two to four months to live because the cancer has spread throughout her body. The only comfort Father Michael gives is his honesty in saying that death is a mystery and one can’t say much about it. However, the most accurate and hopeful comment he tells her is that the doctors don’t know everything. In other words their prognosis may be wrong. Father Michael ends any further discussion of Marta’s cancer and shifts to another topic abruptly which is humorous. Then the action gyrates so that Dan and Marta decide to pick up some beers as if the dire conversation never happened nor should happen. Dan and Marta promise to come back, leaving Father Michael with Jimmy (Hari Nef) in a blonde wig, rhinestone boots, make-up and wheelchair.

Jimmy who has been crippled by a doctor during the sex change operation appears to take this in stride. However, we discover what is motivating Jimmy’s apparent calm later in the play, the hope of walking again. The scene between Nef’s Jimmy and Shannon’s Father Michael is wonderfully acted, free and spot-on quirky. Jimmy tells Father Michael that he heard his parents discussing that Father Michael wears make-up. Father Michael is honest. Jimmy suggests that Father Michael allow him to be his make-up artist. Though Father Michael prefers putting on his own make up, with good will, he lets Jimmy add lipstick, rouge and eye-shadow to his face. The two bond during this amazing scene because the actors are “in the moment” superb.

As Jimmy, Hari Nef is adorably believable without pushing any of “behaviors” to get a laugh. Shannon’s prodigious versatility as an actor has him portray cruel thugs (Bullet Train) and Elvis (Elvis and Nixon) to name a few of his screen roles. As Father Michael he is organic, hysterical and profound. He negotiates the whimsical and empathetic priest with an uncanny and otherworldly aspect. Shannon’s delivery of Father Michael’s most philosophical and trenchant lines is sheer perfection in their tossed away thoughtfulness. It is as if Shannon’s Father peers into another realm, expresses what he sees, then retracts from it like nothing extraordinary has happened, though it has.

To round out the gathering Mrs. Drinkwater (the heartfelt Heather Alicia Simms) shows up looking for the gold wedding band that she gave Dan and forgot to take back. Dan and Marta have not returned with the beers, so Father Shannon and Jimmy introduce themselves and Mrs. Drinkwater tells them that her husband was killed in the plane crash. Abruptly, Father Michael announces that they need to have drinks and specifically, depth chargers (shots dropped in a mug of beer). At this point, the wild party begins and when Dan and Marta return with more beer, the events revolve upside down and sideways as each takes their turn at Karaoke and “lets it all hang out.” Kudos to Hari Nef, Michael Shannon and Heather Alicia Simms for their passionate renditions of their solo numbers.

The fun is in watching the actors enjoy themselves to the hilt and in the process, convey the loneliness and angst each of the characters personally experiences. We appreciate the drunken camaraderie and comfort they share. It is better than that of “old friends” who know “too much” of their pain and torment. Nevertheless, they have just enough information about each other. They understand that they all are imperfect and have experienced loss, uncertainty, confusion. They have been tossed about by life’s seemingly random trials, forced to assign their own meaning to the haphazard and horrible events. Theirs is the sticky understanding that they can help each other through their personal crises that none of them can specifically explain because it can’t be articulated. All they can do is state concrete facts about conditions. But underneath are miles of subsurface emotions, psychic damage, pain, fear, sorrow.

The hope is that they are alive with the determination to keep on “truckin’,” as they receive solace in understanding the ubiquity of their absurd-life-in-death condition. They, like all human beings, roll a metaphoric boulder up a hill, knowing at the top they will slip and fall to the bottom. Then, they will have to do it again and again does Sisyphus of Greek mythology.

For Dan and Marta, the loss of their daughter who overdosed is most acutely felt, a fact they mention then drop. For Mrs. Drinkwater, the loss of her husband has dislocated her and upended her identity about herself. Who is she now and how does she define herself without him? For Nef’s Jimmy, the paralysis is devastating, but it may not be permanent. At one point when Jimmy is alcohol buzzed, he stands up and proclaims that he, “will walk again.” Lastly, Father Michael is negotiating his physical person, his celibacy, his marriage to Mr. Drinkwater (a mysterious notion) and his straddling the otherworldly realms of consciousness and spirit.

Johnson’s play cannot easily be pinned down in its hybrid, comedic absurdism and avant garde elusiveness. It zips along with unlikely and surprising twists with every character dynamic and every character expose. Its strong spiritual themes about life, the afterlife, consciousness and no boundaries between and among these realities, are thought-provoking. The ensemble’s acting is top-notch and their team work reaches a high-point when each performs their solos while the others move into themselves, all creating an exceptional, flowing dance.

Arin Arbus has staged the wildness so that it is zany yet meaningful with the help of Byron Easley (choreographer). Riccardo Hernandez’s scenic design, Qween Jean’s costume design, Scott Zielinski lighting design and Mikaal Sulaiman’s original music and sound design effectively capture the director’s vision and enhance Johnson’s themes about human nature, pain and seeking to escape from it with like-minded others through alcohol or just letting go. In this production, which emphasizes humanity, forgiveness, understanding and empathy, we realize the isolation of individuality and the commonality of emotions whether joyful or sorrowful, that often prompt escapism to crazy, if only for a moment in an eternity of time.

This is one to see. It ends January 8 and runs with no intermission. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.tfana.org/current-season/des-moines/overview