Blog Archives

‘Almost Famous’ The Broadway Musical Gives a Shimmering Nod to 1970s Rock ‘n’ Roll

From the response of the audience’s standing ovation and cheering, the snarky comparison by critics to the lead actors of Almost Famous and Dear Evan Hansen and other criticisms didn’t seem to matter. That is because Almost Famous delivers. This is especially so if one has seen the titular film (2000). If you appreciate a nod to what Howard Stern refers to as the best music of the past (better than the 1960s), and take that love or fandom to The Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, you will be happy you went to see this enjoyable production of Almost Famous directed by Jeremy Herrin.

Written by Cameron Crowe (book and lyrics), and Tom Kitt (music and lyrics), based on the Paramount Pictures and Columbia Pictures film written by Cameron Crowe, the show spreads its uplift and hope during a holiday season that is bringing crowds to Manhattan. Tourists, rockers and Broadway fans up for an entertaining night out will be pleased at the sterling voices, the humor, the energy of the performers and the music which connects the familiar story-line to the historical 70s music scene with nostalgia and poignance.

The classic rock covers (i.e. Deep Purple, the Allman Brothers), sustain us while Kitt’s original music is interesting with memorable songs like “Morocco,” “The Night Sky’s Got Nothing on You,” and “Everybody’s Coming Together.” The new melodies (a combination of rock and pop), convey the heart of the characters who are subtly drawn.

Fandom is the key to frequent successful film to stage transference. It may or may not apply here. The creators have taken a leap into the Broadway musical genre. They’ve created original songs for live performance and they have slipped in songs from the period (Led Zeppelin, Joni Mitchell, Cat Stevens, Lynard Skinner, Stevie Wonder, David Bowie and Elton John) into the musical’s action but not in the same way as in the film, whose background was replete with rock ‘n’ roll songs from start to finish. That doesn’t happen with this musical that has 18 newly-written songs. Included are four reprises from Tom Kitt (music) and Cameron Crowe (lyrics). The songs move the action as the characters express their conflicts, issues, desires and feelings and get tangled up in each others’ agendas.

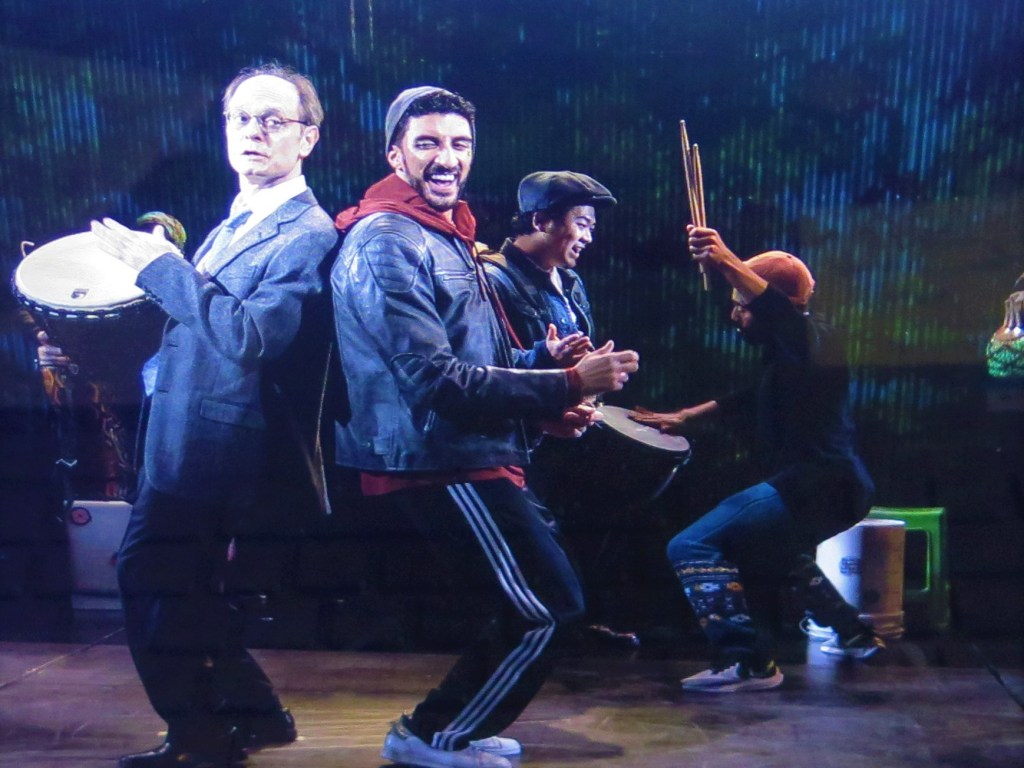

Staged cleverly with Sarah O’Gleby’s movement, director Jeremy Herrin and the creative team eschew traditional choreography and keep the sets simple and minimalist to suit roadies on tour with the exception of William’s and Elaine’s home. This is in the service of suggesting the free form movement of the 1970s. The concept of great rock was fading into new musical trends like Rap then moved in the 1980s to MTV domination. Ultimately, the musical is a nod to 1970s rock ‘n’ roll and its ethos before commercialization and digital technology skewed it into something else.

Though the action is condensed with the added musical numbers, the arc of plot development, based on Crowe’s real-life journey as a teenage rock writer, follows the film. Wisely, the humorous lines in the production are lifted from Crowe’s writing, which won an Oscar for best original screenplay (2001).

One of the most important themes of the musical reveals an ambience of the 1970s, that was culturally strained between liberalism and conservatism. This is partly suggested by the opening number “1973,” when William Miller (the excellent Casey Likes), confesses to rock ‘n’ roll critic Lester Bangs (a manic, funny Rob Colletti). William sings about his conflicts with his mom. She stands in the way of his discovering “who he is.” In a state of flux, his mother Elaine (the humorous Anika Larsen), a teacher fearful of “drugs, sex and rock ‘n’ roll,”controls William and his sister Anita to the point where Anita (Emily Schultheis), rebels and leaves home.

However, Elaine can’t quite figure out who she is either. She adopts a healthy vegetarian/vegan lifestyle, clearly a liberal cultural influence. Yet, conservatively, she disagrees with subversive music (the rock ‘n’ roll Anita loves), and its cultural aftereffects (sex, drugs, wild partying). The pull of conservatism and liberalism is one William faces in his conflict with Elaine, but he’s leaning toward the underground and subversive, reinforced when his sister gives him all her rock ‘n’ roll albums to be “cool.” These inspire him to write for his school newspaper with the hope of a possible career as a writer or future music critic.

One element of his confusion, unbeknownst to him. is that his mother had him skip grades and lied about his age. Meanwhile, he is embarrassed because he has no pubes, is alone, uncool and alienated by classmates who humiliate him. Naturally, when he receives a response from Lester Bangs, the finest rock critic in Christendom, who accepts and encourages him, he jumps at the chance to write for Bangs’ Creem Magazine. On the road to being a bone fide critic, he lands an assignment from Rolling Stone to profile a rising band called Stillwater.

William manages to obtain Elaine’s permission by swearing he will remain pure and stay away from drugs and sex. Elaine relents because she dimly thinks it is better to connect with him and “keep him near,” (which fails), rather than lose him like she lost Anita. Ironically, she loses him in a different way. The rock band “kidnaps her son,” a funny and wonderful refrain in “Elaine’s Lecture” which is a lament that carries her angst about what is happening to William. He goes on the road with the band to get an interview, for which Ben Fong-Torres (Matthew C. Yee), will pay him handsomely. It’s an opportunity too good to pass up.

Likes’ William enjoys the excitement of “getting down” with beautiful young women who assist bands in their mission to be great. These groupies, cheering the praises of their leader Penny Lane (Solea Pfeiffer), have re-branded themselves as The Band-Aids. They are rock ‘n’ roll muses and their mission is “all about the music.” Indeed, Penny Lane has so fulfilled her role, that musicians have written 14 songs about her, and “all of them good,” affirms Estrella (Julia Cassandra).

With such a build-up of excitement Likes’ William is smitten with Penny (Solea Pfeiffer), and her Band-Aides who, along with Estrella, include Sapphire (Katie Ladner) and Polexia (Jana Djenne Jackson). Solea Pfeiffer is an “all that” Penny Lane who doesn’t quite convince us that she is about the music and so “cool” and scintillating to musicians, that she is their fount of inspiration. But then she is not supposed to. The Band-Aids, Penny and Stillwater’s Russel Hammond (Chris Wood), Jeff Bebe (wild, rocking Drew Gehling), Larry Fellows (Matt Bittner), and Silent Ed (Brandon Contreras) are “hype.” The actors (the Band-Aids and Stillwater), do a superb job of managing their characters’ “cool” with enough awkwardness for us to know that they are “almost famous,” but not there yet. And as a result, they will never really achieve super stardom because they get in each other’s way and are totally “uncool.”

The Band-Aides and Stillwater must walk the tightrope of not believing their own image to avoid falling into a destructive abyss which threatens throughout. This conflict and tension abates after the moment of truth on the airplane, especially when Woods’ Hammond and Gehling’s Jeff Bebe reveal their deepest secrets because they fear the plane will crash. This scene is technically delivered to surprising effect. Humorously, the tiny jet “flying” on a chord from one side of the stage to the other was so “over-the-top,” it worked in the service of farce.

The actors did a great job with the scene to convey just enough humor and fear to “spill the beans” and further wreck Stillwater’s “togetherness.” Believing their own hype brought them to facing this catastrophe on the plane. If they continued to take their humble tour bus, they would have been safer. The real dose of reality that Hammond says he wants is a pose only revealed when he thinks he’s going to die. Thanks to Derek McLane (scenic & video design), Natasha Katz (lighting design), Peter Hylenski (sound design), and the actors’ authenticity, the scene embodies their magical thinking vs. truth, a key conflict and theme of the musical.

Williams’ adventures initially captured in his journey through the songs, “Who Are You With?,” “Ramble On,” “Penny and William,” “Fever Dog,” and “Morocco,” evidence the pitfalls of being a rock ‘n’ roll critic who is always a “watcher” of the action, not a creator of it. Colletti’s Bangs humorously warns William to be “honest and unmerciful.” When William gets a taste of the band culture, its groupies and the challenge to be accepted, he tries not to be overwhelmed or lose his “objectivity.” Yet, he succumbs to their manipulations. First, there’s the rejection of him as a critic (called “The Enemy” by Stillwater’s Jeff Bebe). This wears him down and makes him want to “fit-in.” Though he resists and manipulates band members with flattery, he never adheres to Lester Bangs’s sage advice. Gradually, William is sucked in because Stillwater’s Bebe, Hammond and Penny Lane are good at “the game.” William is clever, but he’s a neophyte.

This “congenial” conflict between William, the band and Penny Lane disappears when he believes he is a friend, (“Something Real,” “No Friends,” the healing of divisions with “Tiny Dancer,” “Lost in New York City, Pt. 1” and “River/Lost in New York City Pt. 2”). But this “friendship” is a blind and his presumed love with Penny Lane eventually clarifies for him when she leaves him to the Band-Aids and joins Hammond (“It Ain’t Easy”). He is discouraged, but hangs on and writes a piece for Rolling Stone. However, it is rejected by fact-checker Allison (Emily Schultheis), and he is accused of writing a puff piece that Stillwater encouraged him to write. Only until Wood’s Hammond finally verifies William’s honest and “unmerciful” article to Rolling Stone, is the “magical fake world” of the band blown apart. However, this is beneficial for it allows the band and groupies to begin a new day.

Through lines in characterization are consistently effected. The conflict between son and mother abides from start to finish and provides much of the humor. Anika Larsen deftly balances Elaine as a typical loving parent, whose concern, knowledge and control are acceptable to the audience. She is never acerbic or preachy in the songs “He Knows Too Little (And I Know Too Much),” “Elaine’s Lecture,” and “Listen to Me.” Resolutions occur by the conclusion, when Anita has found herself and the full company sings the reprise of “Everybody’s Coming Together,” a rousing standout.

The actors, shepherded by Jeremy Herrin, do an excellent job of precluding who will end up on the floor of their own demise. This is strongest when we note the rifts between Bebe and Hammond, beginning when the T-shirts are distributed, then moving to the partial healing of their divisions on the bus with the singing of “Tiny Dancer,” another knockout scene and high-point at the conclusion of Act I. Though manager Dick Roswell (Gerard Canonico), has brought them together for a while, the conflicts among band members continue. They encompass Penny Lane and Russell’s relationship. Penny Lane is sold out in a bet that William witnesses during the Poker game scene. Pfeiffer’s Penny Lane and Likes’ William are excellent together with resonating lyricism and power when he saves her life after she overdoses on Quaaludes.

Most of the new songs work. Additional strong scenes/songs include Penny and William’s “The Real World,” Russell and Penny Lane’s “The Night-Time Sky’s Got Nothing on You” and “Something Real” when Woods’ Hammond falls apart at a fan’s house. At this point before the end of Act I, William attempts to keep Russell away from acid and fails. Woods and Likes do an excellent job revealing the negative pressure on their characters from the hype that Wood’s Hammond attempts to escape. It is an irony that he can’t because he is as needy and “uncool” as Penny Lane, Jeff Bebe and the others. However, he just hides it better.

Interestingly, in his immersion with the band, the only time they all come out of their “image” is when Likes’ blows it up with the final Rolling Stone piece about them, something that Wood’s Hammond encourages and has yearned for. Then, even Penny Lane is able to gain the strength to go to Morocco, leading to a satisfactory conclusion with “Fever Dog Bows,” which the entire company sings as a tribute to 1970s rock ‘n’ roll.

Kudos to the creative team already mentioned with special praise for Bryan Perri’s music supervision and direction, and Lorenzo Pisoni as physical movement coordinator. This is one to see for the shimmering performances, rousing music and nostalgia for a time we will never see again in its wacky innocence and silly “hedonism,” which seems quaint viewed through our current perspective. For tickets and times go to their website: https://almostfamousthemusical.com/

‘The Visitor,’ Not to be Underestimated, Extended at The Public

The Visitor, is a haunting musical based on Thomas McCarthy’s resonant, titular, award-winning film (2007). In its World Premiere, The Visitor has been extended at The Public Theater, and is ending December 5th, 2021. That we are able to see it at all, given the pandemic which made New York City the global epicenter of death, shuttering theater for months, is nothing short of miraculous.

The egregious hell of the previous administration, including its threatened overthrow of the nation led by the former president and white supremacists who oppose immigration and the constitutional rule of law, may influence one toward a jaded view of The Visitor as woefully “uncurrent.” Some critics suggested this. Indeed, that is dismissive of the musical’s inherent hope, goodness and prescience. Not to view it through the proper lens of historical time would be as limiting as the unjust institutions and failed immigration policies that the production thematically indicts.

The Visitor, acutely directed by Daniel Sullivan, takes place after 2001 during the administration of President George W. Bush Jr., when certain groups viewed Muslim immigrants as possible terrorists. The period 2001-2007 was a less divisive time in the nation, but our failed immigration policies did stagnate and worsen, setting us up for future debacles and the growth of white domestic terrorism. Nevertheless, if one’s sensibilities are too upended by the traumas of the Trump administration to enjoy the musical without keeping the 2001-2007 time period in mind, the themes and the human core of this work by Tom Kitt (music), Brian Yorkey (lyrics), Kwame Kwei-Armah & Brian Yorkey (book), will be overlooked and given short shrift.

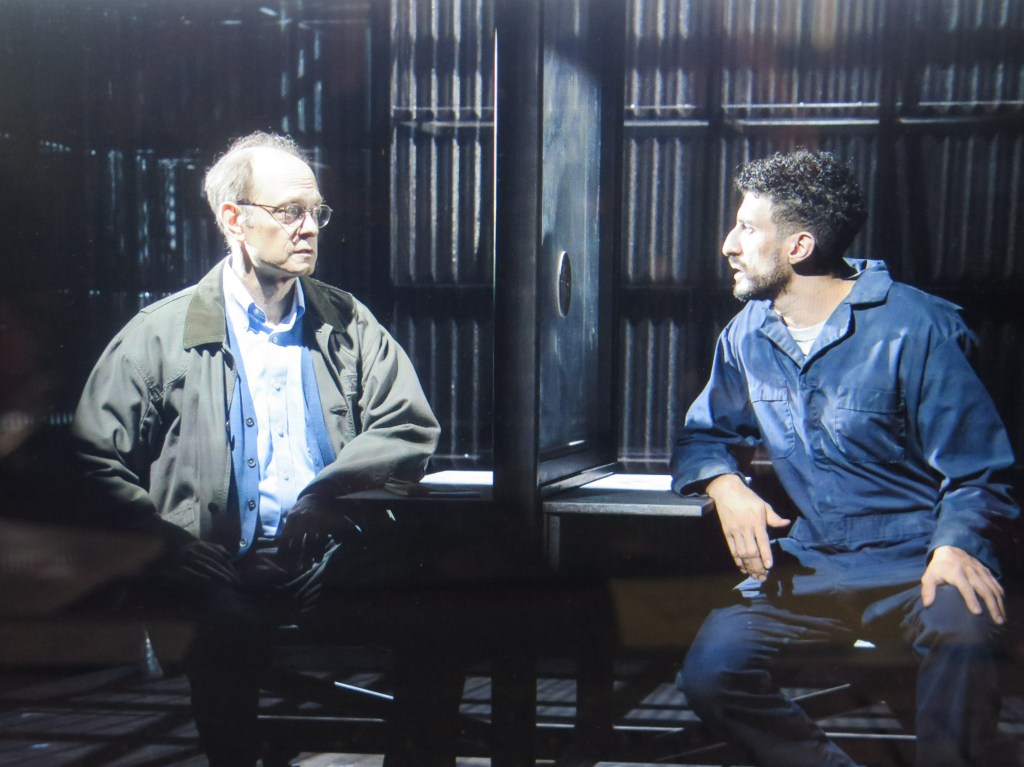

The themes are relayed principally through the relationships established between white college professor Walter (David Hyde Pierce in an emotional and effecting portrayal), Syrian Tarek (the likeable Ahmad Maksoud), and his girlfriend from Senegal, Zainab (the golden voiced Alysha Deslorieux). Believing Walter’s Manhattan apartment has been vacated, Tarek and Zainab, tricked by an “Ivan,” have been staying there without Walter’s knowledge. What occurs after Walter discovers their presence, takes us back to a time before Donald Trump’s inhumane immigration policies, Republican party nihilism and Democratic governors’ establishment of sanctuary cities to protect the undocumented and waiting asylum seekers.

The opening numbers (“Prologue,” “Wake Up,” “Voices Through a Window”), establish why Walter is amenable to not behaving like a guard dog (who would note Zainab’s accent and Tarek’s swarthy looks), and immediately call the police to arrest the couple. Walter is a professor, not law enforcement. However, Zainab sees the precariousness of their situation and with passion mitigates their mistake (Zainab’s Apology”). After they leave, Walter finds Zainab’s sketch pad and runs after them. What results is an act of hospitality and generosity, as he allows the couple to stay until they find somewhere else to go.

Walter’s state of mind, character, background and the loss of his wife and emotional destitution prompt this irregular action. On the couple’s part, Zainab, who has been through an undocumented female’s hell which we later discover (“Bound for America”), doesn’t trust Walter and presses Tarek to leave, despite their desperate circumstances. David Hyde Pierce, a consummate actor whose Walter floats like a ghost without any sense of purpose, mission or happiness, sparks to interest identifying with the couple’s romantic love (“Tarek and Zainab,”). He wants to trust in their goodness and decency because he has already lost everything worth anything to him and he has nothing left to lose.

Walter, Tarek and Zainab take this incredible risk because of their overwhelming needs. All are visitors to this land of human decency which they extend to each other with hope and a faith that grows and changes their lives. When Tarek teaches Walter how to play one of his djembes (a goblet drum played with bare hands that originated in West Africa), and takes him to the park to play with others (the incredible “Drum Circle”), a bond is formed that will never be broken.

The production’s music (thanks to Rick Edinger, Emily Whitaker, musicians and the entire music team), solidifies the themes of friendship, unity, empathy, humanity. Significantly, the music suggests another vital theme. It is through our cultural differences via artistic soul expression, that the commonality among all of us may best be found. These themes, during what appears to be the height of racism and white supremacy in our nation today must be affirmed more than ever. The Visitor does this with subtlety like a grand slam in bridge played with three cool finesses.

At the first turning point in the production, the center starts to give way. Though Walter tries to advocate for the inaccuracy of the transit cops’ charges, Tarek is arrested for “jumping” a subway turn style after he pays but can’t fit himself and his drum through it. The cops’ action underscores the inequity of the justice system. If he were white, they probably wouldn’t arrest him. The cops find it “inconvenient” to believe Tarek’s explanation. Nor do they follow Walter’s advice to check his card to verify Tarek’s truthfulness.

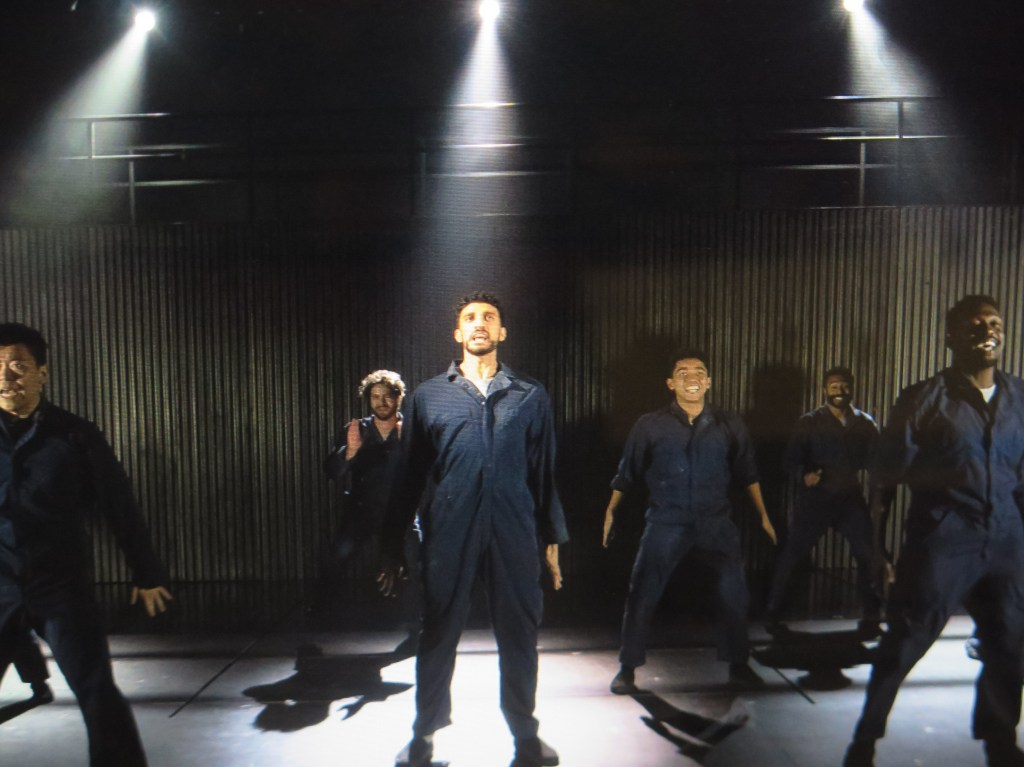

Discovering Tarek is undocumented, they put him in a detention center in Queens. Feeling responsible for Tarek’s situation, Walter hires an attorney, visits Tarek and keeps Zainab encouraged. It is in the detention center that we note the cruelty toward the undocumented, who are treated as criminals, though they are asylum seekers and willing to work for a better life for themselves. The music, lyrics and Lorin Latarro’s choreography, especially in “World Between Two Worlds” sung by Tarek, Walter and the Ensemble are superbly expressive, heart-wrenching and powerful.

As the stakes become higher in the second turning point, Tarek’s mother Mouna (the effecting, soulful Jacqueline Antaramian), visits Walter’s apartment looking for Tarek. Events complicate. Walter finds Mouna appealing and authentic. Mouna and Zainab ride the Staten Island Ferry. They finally become friends (“Lady Liberty”), and share how they believed the seductive promises of the “American Dream.” Because Mouna and Zainab may never see Tarek again in the U.S., Walter becomes the one they must turn to (“Heart in Your Hands,” “Blessings,” “Such Beautiful Music.”). Beyond hope (“What Little I Can Do”), Walter does his best, but the institutions fail him as they have failed us for years.

It is through the relationships with Tarek, Mouna, Zainab that Walter’s humanity and empathy are stirred to change his soul and his direction in life. It is the love for Tarek and the hope of his release that changes Mouna’s and Zainab’s relationship with each other. And their relationship with Walter establishes a new level of understanding that there are “good” people who will help. Finally, it is the stirring of Tarek’s concern for Zainab, that helps him realize his spiritual love and connection with her is not bounded by the material plane (“My Love is Free”), or held in by the walls of his jail cell, or deportation back to Syria. And it is that spiritual love for her and his connection to Walter that will help him face whatever he encounters.

As an archetype for all sane individuals, Walter realizes the issues underlying Tarek’s, Zainab’s, Mouna’s situation. We are to agree with him, the creative team hopes. These individuals are not “the other” that their nationless position or the white supremacists’ stereotyping suggests they are: dangerous, encroaching, grifting. In the showstopping “Better Angels,” David Hyde Pierce prodigiously, emotionally expresses his song-prayer for Tarek. He petitions against the injustice of Tarek’s situation. Our nation should act better, but it has become unmoored from its founding ideals of liberty and the inalienable rights of human beings (“We hold these truths to be self-evident…”).

As Pierce sings, the irony of an older, white gentleman whose life has been bled out of him, standing in the gap for a young undocumented Syrian, who is full of vitality and hope, wanting to live his life to the fullest in a country that doesn’t deserve him, is beyond fabulous. It is also heartbreaking. Pierce, impassioned, speak/sings it out into the nether regions of spiritual consciousness. Is anyone listening? Have we forsaken our citizen right to help others?

I apologize for being moved for I thought of what was to come because of these failed immigration policies which continued and inspired the former President Donald Trump’s white supremacist agenda: kids in camps at the Southern Border, kids lost to parents for years, the undocumented dying in stifling heat and horrific conditions, proud Trumpers appreciating Steven Miller’s cruelty, while donating to grifter Steve Bannon’s fake “Build the Wall” fund.

The Visitor presciently, horrifically intimates what happens if injustice and cruelty are institutionalized and the populace is inured to it or worse, uses xenophobia as a whipping post to domestically terrorize others for pleasure’s sake. White supremacists have evolved to do so precisely because of failed immigration policies which a craven, unhinged politician exploits for his own grifting agenda.

Equally terrifying is the war of attrition against decency, and the lack of wisdom to appreciate this historically as revealed by The Visitor. If we consider that critics are inured/jaded not to see in The Visitor the failed state of our culture in 2001-2007, that augmented during and after the Obama administration, the loss of that understanding bears reviewing. And while many were thrilled with former President Obama, in the shadows, white supremacy groups grew by demonizing “the other.” Sadly, they blossomed to a “first wave,” who supported a president against democratic values, one who followed up with inhuman, indecent acts from immigration crimes to COVID deaths.

The character of Walter reminds white males it’s OK to be humane and decent and empathetic. To think this production is not “current” enough via its historical perspective is misguided.

In Kitt’s, Yorkey’s, Kwame Kwei-Armah’s musical, Tarek and Mouna symbolize the courageous willing who take horrific risks. We need to be reminded of this again and again. Sullivan’s profound direction prompts the musical to change our perspective through empathy and identification. Thematically, The Visitor suggests we no longer allow ourselves to be like inconsequential stones kicked around by politicians. What is it like to sustain the impossible hardship of leaving all that was familiar and comforting in the hope of escaping catastrophe, only to never gain the security sought (“Where Is Home?/No Home”)? As climate change continues to roil the planet and immigration issues worsen, we can’t drop a stitch of understanding or subdue an impulse to assist in whatever way we can.

The actors/singers, phenomenal swings, musicians and creative team stir us to listen to the production’s call to arms. We must reform our failed immigration policies that have caused horrific pain for asylum seekers and dreamers, as they wait for citizenship to no avail. Not only must changes be made, they must be made permanent so that no Executive Order, lawsuit or state can reverse it to pleasure white supremacists.

Specific shout outs to David Zinn’s evocative scenic design: the steel backdrop of the detention center and its ironic contrast, Walter’s comfortable apartment. Kudos to Toni-Leslie James (costumes), Japhy Weideman (lighting), and others who helped to make The Visitor a compelling, must-see production. For tickets and times visit the website: CLICK HERE.