Blog Archives

‘Liberation’ Transfers to Broadway Solidifying its Excellence

Bess Wohl’s Liberation directed by Whitey White in its transfer to Broadway’s James Earl Jones Theater until January 11th doesn’t add references to the 2024 election nor the disastrous aftermath. However, the production is more striking than ever in light of current events. It reaffirms how far we must go and what subtle influences may continue to derail the ratified ERA (Equal Rights Amendment) from becoming settled law.

To draw parallels between the women’s movement then and now, Wohl highlights the “liberation” of the main character/narrator Lizzie, an everywoman, with whom we delightfully identify. With Lizzie (the superb Susannah Flood) we travel along a humorous journey of memory and self-reflection as she evaluates her relationship to her activist mom, who gathered with a community of women in Ohio, 1970 to “change the world and themselves.”

Wohl’s unreliable, funny narrator, directs the action and also is a part of it. The playwright’s smart selection of Lizzie as a device, the way in to tell this elucidating story about women evolving their attitudes, captures our interest because it is immediate. Her understanding is ours, her revelations are ours, her “liberation” is also ours. Lizzie shifts back and forth in time from the present to 1970-73, and back to the present. One of the questions she explores concerns why the women’s movement cascaded into the failures of the present?

Assuming the role of her mother, Lizzie enacts how her mom established a consciousness-raising group. Such groups trended throughout the country to establish community and encourage women’s empowerment. Six women regularly meet in the basement basketball court at the local rec center which serves as the set throughout Liberation, thanks to David Zinn’s finely wrought stage design. The group, perfectly dressed in period appropriate costumes by Qween Jean, includes a Black woman, Celeste (Krisolyn Lloyd), and the older, married Margie (Betsy Aidem).

Having verified stories with her mom (now deceased), and the still-living members of the group, Lizzie imagines after introductions that the women expansively acknowledge their hope to change society and stand up to the patriarchy. As weeks pass they clarify their own personal obstacles and their long, bumpy road to change, with ironic surprises and setbacks.

For example, Margie voices her deeper feelings about being a slavish housewife and mother. After months of prodding, her husband actually does the dishes, a “female” chore. Margie realizes not only does she complete housework faster and better than he, but her role as housewife and nurturer satisfies, comforts and makes her happy. Betsy Aidem is superb as the humorous older member, who introduces herself by announcing she joined, so she wouldn’t stab her retired husband to death.

Some members, like Sicilian-accented Isidora (Irene Sofia Lucio), and Lloyd’s Celeste, belonged to other activist groups (e.g. SNCC). Circumstances brought them to Ohio. Isidora’s green-card marriage needs six more months and a no-fault divorce, not possible in Ohio. Celeste, a New Yorker, has moved to the Midwest to take care of her sickly mom. The role of caretaker, dumped on her by uncaring siblings, tries her patience and stresses her out. Expressing her feelings in the group strengthens her.

Susan (Adina Verson) is an activist burnt out on “women’s liberation.” Frustrated, Susan has nothing to say beyond “women are human beings.” She avers that if men don’t treat women with equality and respect, then women’s activism is like “shitting in the wind.”

Lizzie and Dora (Audrey Corsa) discuss how they suffer discrimination at their jobs. Despite her skill and knowledge Lizzie’s editor demeans her with “female” assignments (weddings, obituaries). Dora’s boss promotes men less qualified and experienced than Dora. Through inference, the playwright reminds us of women’s lack of substantial progress in the work force. Very few women break through “glass ceilings” to become CEOs or achieve equal pay.

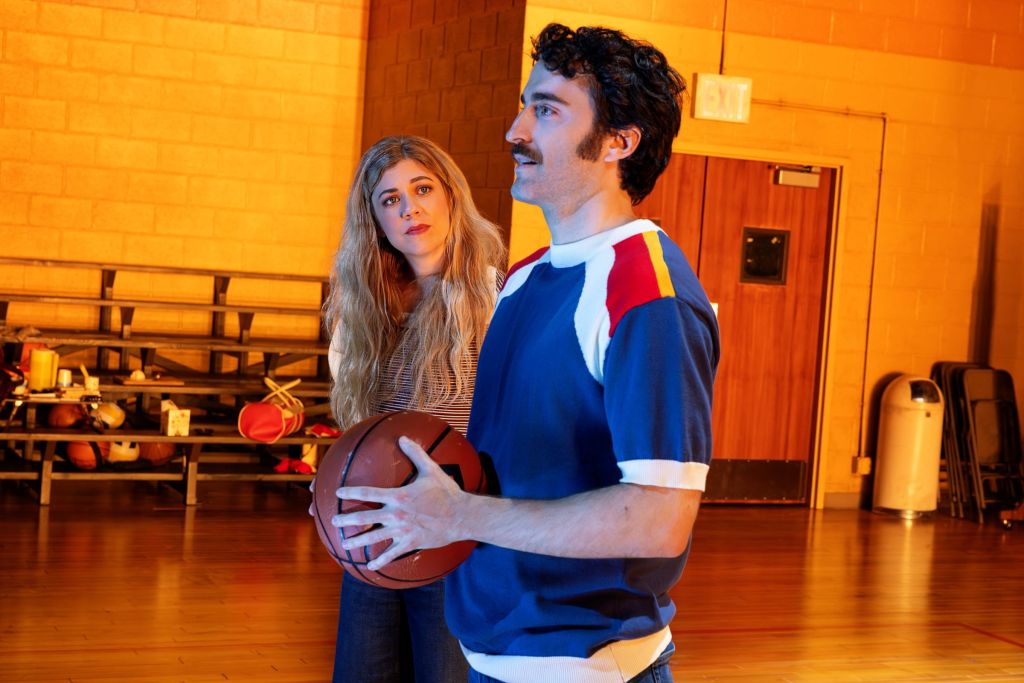

Act I engages because of the authentic performances and various clarifications. For example, Black women have a doubly difficult time at overturning the patriarchy. Surprisingly, at the end of the act a man invades their space and begins shooting hoops. Is this cognitive dissonance on Lizzie’s part for including him? Have women so internalized male superiority that they become misdirected back to the societal default position of subservience? Is this what thwarted the movement?

When Lizzie refers to the guy as Bill, her father (Charlie Thurston), we get the irony. How “freeing” that her mom meets her dad as she advocates for liberation from male domination, only to be dominated by an institution (marriage) constructed precisely for that purpose.

Act II opens with additional dissonance. To extricate themselves from the psychological trauma of men’s objectification of their bodies, the women free themselves from their clothes. Sitting in the nude, each discusses what they like and dislike about their bodies. The scene enlivened heterosexual men in the audience, an ironic reinforcement of objectification. We understand that these activists try to overcome body shame that our commercial culture and men use to manipulate women against themselves and each other (surgical enhancements, fillers, face lifts, etc.). On the other hand the scene leaves a whiff of “gimmick” in the air, though Whitney White directs it cleverly.

After the nude scene Lizzie reimagines how her mom and Bill fell in love. To avoid discomfort in “being” with her father, she engages Joanne (Kayla Davion), a mother who drops into the rec room looking for her kids’ backpacks. Through Bill and Joanne’s interaction, we note the relationship that Lizzie keeps secret. When Lizzie finally reveals she is engaged, the dam bursts and each of the women reveals how they have been compromising their staunch feminist position. One even admits to voting for Nixon with a barrage of lame excuses.

This scene is a turning point that Lizzie uses to explore how women in the movement may have sabotaged themselves at advancing their rights. Reviewing her mother’s choice to get married and co-exist as a feminist and wife, Lizzie reimagines a conversation with her deceased mother played by Aidem’s Margie in an effecting performance. When Lizzie asks about her mom’s happiness, Margie kindly states that Lizzie has gotten much of her story wrong.

Lizzie condemns feminism’s failures. This is the patriarchy, internalized by Lizzie, speaking through her. With clarity through Margie’s perspective, Wohl reminds us that all the stages of the feminist movement have brought successes we must remember to acknowledge.

Lizzie realizes the answer to whether one might be “liberated” and fall in love and “live equitably” within an institution which consigns women to compromise their autonomy. It depends upon each individual to make her own way. Her investigation about her mother’s consciousness-raising group establishes the first steps along a journey toward “liberation,” that she and the others will continue for the rest of their lives.

Liberation runs 2 hours, 30 minutes with one intermission at the James Earl Jones Theater through Jan. 11th. liberationbway.com

‘Saturday Church’: The Vibrant, Hot Musical Extends Until October 24th

With music and songs by Grammy-nominated pop star Sia and additional music by Grammy-winning DJ and producer, Honey Dijon, Saturday Church soars in its ambitions to be Broadway bound. The excitement and joy are bountiful. The music and songs, a combination of house, pop, gospel spun into electrifying arrangements by Jason Michael Webb and Luke Solomon, also responsible for music supervision, orchestrations and arrangements, become the glory of this musical. Finally, the emotional poignance and heartfelt questions about acceptance, identity and self-love run to every human being, regardless of their orientation and select gender identity (65-68 descriptors that one might choose from).

Currently running at New York Theatre Workshop Saturday Church extends once more until October 24th. If you like rocking with Sia’s music, like Darrell Grand and Moultrie’s choreography and Qween Jean’s vibrant, glittering costumes, you’ll have a blast. The spectacle is ballroom fabulous. As J. Harrison Ghee’s Black Jesus master of ceremonies says at the conclusion, “It’s a Queen thing.”

However, some of the narrative revisits old ground and is tired. Additionally, the music doesn’t spring organically from the characters’ emotions. Sometimes it feels imposed upon their stories. Perhaps a few songs might have been trimmed. The musical, as enjoyable as it is, runs long.

Because of the acute direction by Whitney White (Jaja’s African Hair Braiding), the actors’ performances are captivating and on target. Easily, one becomes caught up in the pageantry, choreography and humor which help to mitigate the predictable story-line and irregularly integrated songs in the narrative.

Conceived for the stage and based on the Spring Pictures movie written and directed by Damon Cardasis, with book and additional lyrics by Damon Cardasis and James Ijames, Saturday Church focuses on Ulysses’ journey toward self-love. Ulysses (the golden Bryson Battle), lost his father recently. This forces his mother to work overtime. Unfortunately, her work schedule as a nurse doesn’t allow Amara (Kristolyn Lloyd) to see her son regularly.

Though the prickly Aunt Rose (the exceptional Joaquina Kalukango), stands in the gap as a parental figure, the grieving teenager can’t confide in her. Even though he lives in New York City, one of the most nonjudgmental cities on the planet, with its myriad types of people from different races, creeds and gender identities, Ulysses’ feels isolated and unconnected.

His problem arises from Aunt Rose and Pastor Lewis (J. Harrison Ghee). Ghee also does double duty as the master of ceremonies, the fantastic Black Jesus. Though Ulysses loves expressing himself in song with his exceptional vocal instrument, Aunt Rose and Pastor Lewis prevent him from joining the choir until he “calms down.” In effect, they negate his person hood.

Negotiating their criticisms, Ulysses tries to develop his faith at St. Matthew’s Church. However, Pastor Lewis and Aunt Rose steal his peace. As pillars of the church both dislike his flamboyance. They find his effeminacy and what it suggests offensive. At this juncture with no guidance, Ulysses doesn’t understand, nor can he admit that he is gay. Besides, why would he? For the pastor, his aunt and mother, the tenets of their religion prohibit L.G.B.T.Q Christianity, leaving him out in the cold.

During a subway ride home, Ulysses meets Raymond (the excellent Jackson Kanawha Perry). Raymond invites Ulysses to Saturday Church and discusses how the sanctuary runs an L.G.B.T.Q. program. With trepidation Ulysses says, “I’m not like that.” Raymond’s humorous reply brings audience laughter, “Oh, you still figuring things out.” Encouraging Ulysses, Raymond suggests that whatever his persuasion is, Saturday Church is a place where different gender identities find acceptance.

Inspired by the real-life St. Luke in the Fields Church in Manhattan’s West Village, Saturday Church provides a safe environment where Christianity flourishes for all. When Ulysses visits to scout out Raymond, with whom he feels an attachment, the motherly program leader Ebony (B Noel Thomas), and her riotous and talented assistants Dijon (Caleb Quezon) and Heaven (Anania), adopt Ulysses into their family. In a side plot Ebony’s loss of a partner, overwork with running activities for the church with little help, and life stresses bring her to a crisis point which dissolves conveniently by the conclusion.

The book writers attempt to draw parallels between Ulysses’ family and Ebony which remain undeveloped. As a wonderful character unto herself, the subplot might not be necessary.

As Ulysses enjoys his new found persona and develops his relationship with Raymond, his conflicts increase with his mother and aunt. From Raymond he learns the trauma of turning tricks to survive after family rejection. Also, Ulysses personally experiences physical and sexual assault. Finally, he understands that for some, suicide provides a viable choice to end the misery and torment of a queer lifestyle without the safety net of Saturday Church.

But all’s well that ends well. J. Harrison Ghee’s uplifting and humorous Black Jesus redirects Ulysses and effects a miraculous bringing together of the alienated to a more inclusive family of Christ. And as in a cotillion or debutante ball, Ulysses makes his debut. He appears in Qween Jean’s extraordinary white gown for a shining ballroom scene, partnering with Raymond dressed in a white tux. As the two churches come together, and each of the principal’s struts their stuff in beautiful array, Ghee’s Jesus shows love’s answer.

In these treacherous times the message and themes of Saturday Church affirm more than ever the necessity of unity over division, and flexibility in understanding the other person’s viewpoint. With its humor, great good will, musical freedom and prodigious creative talent, Saturday Church presents the message of Christ’s love and truth against a pulsating backdrop of frolic with a point.

Saturday Church runs with one fifteen minute intermission at New York Theatre Workshop until October 24th. https://www.nytw.org/show/saturday-church/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22911892225

‘Jaja’s African Hair Braiding,’ Hysterical, Fun, Profound

Jaja’s African Hair Braiding by Jocelyn Bioh in its world premiere at the Manhattan Theatre Club (Samuel J. Friedman Theatre), is a rollicking comedy with an underlying twist that, by the conclusion, turns as serious as a heart attack. Bioah’s characters are humorous, quick studies that deliver the laughs effortlessly because of Bioah’s crisp, dialogue and organic, raw themes about relationships, community, female resilience and the symbolism of hair braiding which brings it all together.

The setting is in Harlem, at Jaja’s Hair Salon where African hair braiding and the latest styles are offered. For those white gals and guys who envy the look of long lovely extensions but are too afraid to don them, it is understandable. You have to have a beautiful face to sustain the amazing, freeing look of long braided tresses that you can fling with a gentle or wild toss, evoking any kind of emotion you wish.

During the course of the play, we watch fascinated at the seamless ease with which the actors work their magic, transforming otherwise unremarkable women into jaunty, confident and powerful owners of their own dynamic presentation. While we are distracted by the interplay of jokes and mild insults and gossip, the fabulous shamans weave and work it.

In one instance, Miriam (the fine Brittany Adebumola) takes the entire day to metamorphose her client Jennifer (the exceptional Rachel Christopher). Jennifer comes into the shop appearing staid, conservative and reserved with short cropped hair that does nothing for her. But once in Miriam’s chair, something happens beyond a simple hairdo change.

After MIriam is finished discussing her life back in Sierra Leone, which includes the story of her impotent, lazy husband, her surprise pregnancy and birth of her daughter by a gorgeous and potential future husband, and her divorce from the “good-for-nothing”, paternalistic former one, Jennifer is no longer. Miriam has effected the miraculous during her talk. Jennifer has become her unique self with her lovely new look. As she tosses her head back, we note Jennifer’s posture difference, as she steps into the power of how good she looks. Additionally, because of Miriam’s artistry, Jennifer is the proud receptor of a new understanding and encouragement. She has witnessed Miriam’s courage to be open about her life. If Miriam can be courageous, so can she.

Jennifer leaves more confident than before having taken part in the community of caring women who watch each other’s backs and hair, which by now has taken on additional symbolic meaning. Incredibly, Miriam works on Jennifer’s braids the entire play. However, what Jennifer has gained will go with her forever. The dynamic created between the storyteller, Miriam, and the listener, Jennifer, is superb and engages the audience to listen and glean every word they share with each other.

On one level, a good part of the fun and surprise of the production rests with Bioh’s gossipy, earthy, forthright characters, who don’t hold back about various trials they are going through involving men, who exploit them. Nor do they remain reticent if they think one of their braiding colleagues has been surreptitiously stealing their clients, as Bea accuses Ndidi of doing in a hysterical rant

Another aspect of the humor deals with the various clients who come in. Kalyne Coleman and Lakisha May each play three roles as six different clients. They are nearly unrecognizable for their differences in appearances. They change voices, gestures, clothing, mien, carriage and more. For each of these different individuals, they come in with one look and attitude and leave more confident, happier and lovelier than before.

Portraying three vendors and James, Michael Oloyede is hysterically current. Onye Eme-Akwari and Morgan Scott are the actors in the funny Nollywood Film Clip that Ndidi imitates.

For women, hair is key. Bad hair days are not just a bad joke, they are a catastrophe. Bioh capitalizes on this embedded social, cultural more. Presenting its glories, she reveals the symbolism of “extensions,” and “new appearances” as they relate to uplifting the spirit and soul of women who are required to look gorgeous.

Above all, Bioh elevates the artists whose gifted hands enliven, regenerate, encourage and empower their clients. Along with Miriam (Brittany Adebumola), these include Ndidi (Maechi Aharanwa), Aminata (Nana Mensah) and Bea (Zenzi Williams). Sitting in their chairs, under their protection, trusting their skills at beautification, we recognize the splendid results, not only physically in some instances but emotionally and psychically.

The only one who isn’t an African braiding artist is Marie (Dominique Thorne). She is helping out her mother Jaja (Somi Kakoma), who owns the salon and who is getting married that day, so she can get her green card for herself and Marie. Jaja who appears briefly in wedding garb to share her excitement and happiness with the women who are her friends, then goes to the civil judge to be married. However, Marie can’t be happy for her mother. Likewise, neither can old friend Bea, who has told the others the man Jaja is marrying is not to be trusted.

Nevertheless, the point is clear. Within the shop there are artists who are working their way toward citizenship. And Miriam is saving money to bring her daughter to the US. Though Bioh doesn’t belabor the immigration issues, but instead, lets us fall in love with her warm, wonderful characters, it is a huge problem for the brilliant Marie, who has been rejected from attending some of the best colleges. Her immigration status is in limbo as a “Dreamer.”

And like other immigrants, she is living her life on hold in a waiting game that is nullifying as well as demeaning because, as Jaja points out repeatedly to her, she can be a doctor or anything she wants. Her daughter, Marie, is brilliant, ambitious and hard working. Taking over the African hair braiding salon is not good enough. She can do exploits. But without a green card, she can do nothing.

Directed by Whitney White whose vision for the play manifests the sensitivity of a fine tuned violin, the play soars and gives us pause by the conclusion. The technical, artistic elements cohere with the overall themes that show the hair salon is a place of refuge for women to commiserate, dig deep and express their outrage and jealousies, then be forgiven and accepted, after a time. It is a happy, busy, brightly hued and sunny environment to grow and seek comfort in.

David Zinn’s colorful, specific scenic design helps to place this production on the map of the memorable, original and real. This salon is where one enjoys being, even though some of the characters snipe and roll their eyes at each other. Likewise, Dede Ayite’s costume design beautifully manifests the characters and represents their inner workings and outer “brandings.” From her costumes, one picks up cues as to the possibilities of what’s coming next, which isn’t easy as the production’s arc of development is full of surprises.

Importantly, Nikiya Mathis’ hair & wig design is the star of the production. How the braiding is done cleverly with wigs so that it appears that the process takes hours (it does) is perfect. Of course the styles are fabulous.

Kudos to the rest of the creative team which includes Jiyoun Chang (lighting design), Justin Ellington (original music & sound design), Stefania Bulbarella (video design), Dawn-Elin Fraser (dialect & vocal coach).

This is one to see for its acting, direction, themes and its profound conclusion which is unapologetic and searingly current. Bioah has hit Jaja’s African Hair Braiding out of the park. She has given Whitney White, the actors and the creatives a blank slate where they can enjoy manifesting their talents in bringing this wonderful show to life. It is 90 minutes with no intermission and the pacing is perfect. The actors don’t race through the dialogue but allow it to unfold naturally and with precision, humor and grace.

For tickets go to the Box Office on 47th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues or their website https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2023-24-season/jajas-african-hair-braiding/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&gclid=CjwKCAjwvfmoBhAwEiwAG2tqzDaZkpYxm9EVbEs9yQ0hCPDF5gTyx9a8iy4yFCkwZxfd3skrmdD8oxoCAfgQAvD_BwE