Category Archives: Film Reviews

Mifune Festival at Film Forum Part II

Film Forum’s Mifune Festival originally titled MIFUNE 100 is running at Film Forum from February 11 through 30 of March. The four week long commemoration of genius Japanese actor Toshirō Mifune’s centennial year in 2020 (he was born on April 1, 1920) was delayed because of the Pandemic. With the infection rate subsiding and as attendance at the festival will require vaccination and masking, the decision was made to open the retrospective on the legendary actor this year. Importantly, for film buffs, the Mifune Festival includes rarities and rediscoveries in 35mm imported from the libraries of The Japan Foundation and The National Film Archive of Japan. It has been programmed by Bruce Goldstein, Film Forum’s Director of Repertory Programming, and Japanese film scholar Michael Jeck.

The 33 films being screened, many of which feature Mifune’s seminal collaboration with director Akira Kurosawa are masterpieces which continue to influence global filmmakers to this day. The commentary in Part II gives a brief review of Mifune and Kurosawa’s collaborations on two films Kurosawa made in 1950, one of which catapulted Kurosawa and Mifune to global stardom and a premier place in global film history. To purchase tickets go to Film Forum’s website: https://filmforum.org/series/toshiro-mifune. For my previous discussions on Mifune’s first films collaborating with Kurosawa (Snow Trail, Drunken Angel and Stray Dog) go to my website: https://caroleditosti.com/2022/02/09/mifune-festival-at-film-forum-february-11-march-30/

Part II

Scandal (1950) Film Forum Screenings

Sunday, February 13 at 12:40

Monday, February 14 at 3:00

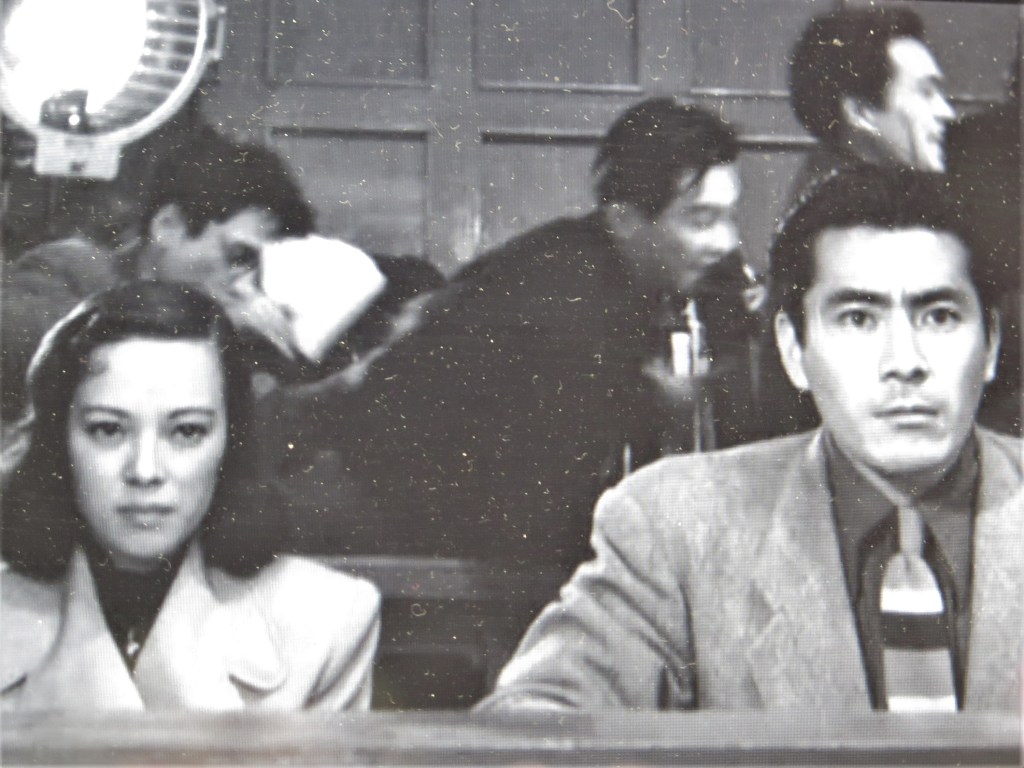

In this 35mm courtesy of the Japan Foundation, Kurosawa presents successful painter motorcyclist Ichirô Aoye (Toshirō Mifune) and attractive singer Miyako Saijo (Shirley Yamaguchi) who meet at a mountain resort with no interest in each other except as casual acquaintances because they principally concerned in furthering their careers. Predatory scandal monger photographers read into their innocent conversation, take photos and show them to their editors and owner of Amour Magazine who, in tabloid fashion right out of Enquirer and Rupert Murdock’s fake entertainment fabrication machine, align the painter and singer as lovers. It’s fabulous profit making copy! Who cares if the story is accurate or not. By the time they may have to retract, they will have boosted their readership and followership and made more money than if they suggested there was nothing untoward between the two. Unlike most celebrities at the time and even today, who ride on the crest of the publicity without taking action, when Aoye sees his photograph and Saijo’s plastered on walls, billboards and “newspapers” as well as the cover of Amour Magazine, he decides to sue for libel.

Enter Otokichi Hiruta (Takashi Shimura) a craven attorney with a weak character and affinity for alcohol and gambling. Hiruta convinces Aoye that he will do a great job with the case and hold Amour Magazine’s editors and owner accountable. When Aoye checks out Hiruta’s decrepit office and sees the racing papers, he understands immediately who Hiruta is and recognizes his capabilities are subpar, recognizing his friend suggestion’s not to hire this dangerous man has merit. However, visiting Hiruta’s home, Aoye meets Hiruta’s wife and angelic daughter Masako (Yôko Katsuragiho). She has been trying to recover from Tuberculosis for years and is incapacitated in bed. Overcome with sympathy and a sense of duty to help the family where Hiruta obviously fails, Aoye allows Hiruta to take his case for the sake of Masako.

Corruption and predation breeds lies and bribes. Aoye, an artistic personality, yet a successful painter is not bluffed by Hiruta, yet he gives him the benefit of the doubt and says he has faith that Hiruta will do the “right thing.” Aoye cares more to encourage Masako, who tells him her father has a good heart but is a weak man and Aoye agrees with her as both hope his nature improves. However, after days in court Hiruta doesn’t even cross examine witnesses properly. However, Hiruta’s weakness is so acute as it is beyond the pale even for Masako who can no longer abide by what she knows to be of her father’s character and unethical behavior in tanking Aoye’s and Saijo’s libel suit.

The tension and frustration we feel is palpable, even horrific, for it is apparent that Hiruta will not change his demeanor in prostituting himself to Amour Magazine despite stabbing his client in the face in betrayal. Meanwhile, Amour Magazine’s owners and editors appear to be sanctified and just. We groan that this is one more instance where the corrupt smash down the ethical and righteous, that evil, slime humanity colludes and conspires to overthrow what is ethical and right making this world a greater cesspool than it already is. This is Kurosawa at his finest thematically! The mendacity of the press that Kurosawa reveals in 1950 remains unchanged; to say this film is prescient is an understatement.

Kurasawa’s direction of the actors and capture of the close-ups of the empathetic, kind Mifune, humiliated but firmly corrupt Shimura and broken-hearted, angel Katsuragiho are genius. Indeed, the performances of the steadfast, quiet, likable Mifune’s Aoye and the wormy, egregious Shimura who grovels in guilt, but does nothing to correct himself, engage us throughout, heightened by the performance of Katsuragiho who is the innocent, sacrificial lamb. Thus, the film’s tragic turning point which reveals Kurosawa’s felt, profound knowledge of human nature, salvation, redemption and damnation carries us through to the end and especially the suspenseful last fifteen minutes of the film which becomes a reckoning. Thematically, Kurosawa’s work undergirded by his great actors is timeless and especially vital for us today.

Rashomon (1950) Film Form screenings

Friday, February 11 at 2:55, 7:10

Wednesday, February 15 at 5:35

Friday, March 4 at 3:50

Saturday, March 5 at 12:40

Wednesday, March 9 at 6:00

Thursday, March 10 at 12:40, 5:10

Perhaps one of the most memorable of all examples of cinematic story telling is Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, based on Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story “In a Grove,” which includes other elements of Akutagawa’s other short story, Rashōmon.” Kurosawa who based his screenplay on Akutagawa’s work twits our comprehension of individual perception and perspective and even twits the film medium itself as an alternate way of understanding our lives in story form.

Five stories are told in Kurosawa’s film, including the philosophical frame of universal focus that contains the other stories within it. The frame setting is a broken-down Shinto Temple, evidence of a faith diminished and destroyed by the encroaching inviolate social constructs and corrupted values in the Heian period Koyoto (794-1185). A Woodcutter (the always wonderful Takishi Shimura) and a priest (Minoru Chiaki) appear shell shocked and stunned as they wait under cover of the temple (symbolic irony) for a furious thunderstorm to pass.

A commoner (Kichijirô Ueda) joins them to get out of the rain and the Woodcutter and priest relate the story of the testimony they’ve just heard at a trial of a Samuri’s murder. The irony is that the priest and the Woodcutter are less disturbed by the killing and rape than by the accounts of the bandit, the raped wife of the murdered Samuri and the psychic who allows the Samuri to speak through her to relate what “really” happened in the grove where a life was taken. Then Kurosawa in flashback allows the three who were involved in the murder to confess their story of what happened.

As each of the witnesses relate their stories, they cast themselves as the heroes of their own myths reflecting the finest aspects of the identity they wish to present, coupled with the codes and values they hope to emphasize, thus manifest to persuade the judges and all present they are the truth teller. Thus, told from the perspective and identity of the bandit, the wife, and the dead Samuri’s spirit, the stories wildly diverge. The only thing agreed upon is that there was a rape and the Samuri was killed. However, whether the wife yielded to the bandit is a matter of question and how the Samuri was killed, whether it was in an unconscious rage by the wife, noble harikari by the Samuri or a valiant combat between the Samuri and the bandit is up for grabs. Not even Solomon the Judge of Israel, the most wise judge of all time could rule in this case where the truth is amorphous and vague and either everyone is lying or one individual is telling the truth.

Considering that someone is going to be punished for the death of the Samuri, no one is pointing the finger at the others for causing the Samuri’s death. This is what perplexes the Woodcutter and the priest. Meanwhile, the practical commoner doesn’t quite understand how clever each of the story tellers are and calls them liars. He misses the conundrum posed. For the three players in this triumvirate of truth-telling take responsibility for killing the Samuri upon themselves. Whether this is a ruse to escape punishment, a conspiracy of silence or an example of the nihilistic ego which places nobility and honor of identity ahead of safety and security from capital punishment is equally opaque. Ironically, what is also disturbing to the priest and Woodcutter who can only exclaim that what they witnessed was terrible is that the truth and accuracy are not considered a worthy value. Rather each of the individual’s beings are paramount. And the truth of what happened has little to do with the bandit, wife and Samuri who are caught up in their own sentience which may not represent factual reality, if there is such a thing.

Finally, the Woodcutter tells his version of the story which proves that the three were lying. In his version their proud identities are shattered and the wife, murdered Samuri and bandit are reduced to the pathetic, pitiable human creatures they are. Interrupting the Woodcutter, a baby’s cries prompt the commoner to steal the items left with the baby and ditch the baby with the priest. We are ba ck to the present and the frame of universal humanity.

The Woodcutter chides the commoner for theft who then turns around and accuses the Woodcutter of stealing the pearl handled dagger that was lost in the chaos, stating that all men are liars and thieves motivated by their own personal agendas. With that exclamation point of the truth about humanity, the commoner leaves, self-satisfied he knows it all and doesn’t need to hear any of the priest’s sermons. Desolate, the priest is ready to renounce his faith and purpose, but the Woodcutter tells him he’ll take the baby and care for it. The priest believes he will harm the baby until the Woodcutter says he has six children at home. What is one more? Faith is restored, the rain stops, the sun comes out, but there are still clouds in the sky, typical Kursawa’s philosophical take on what will come.

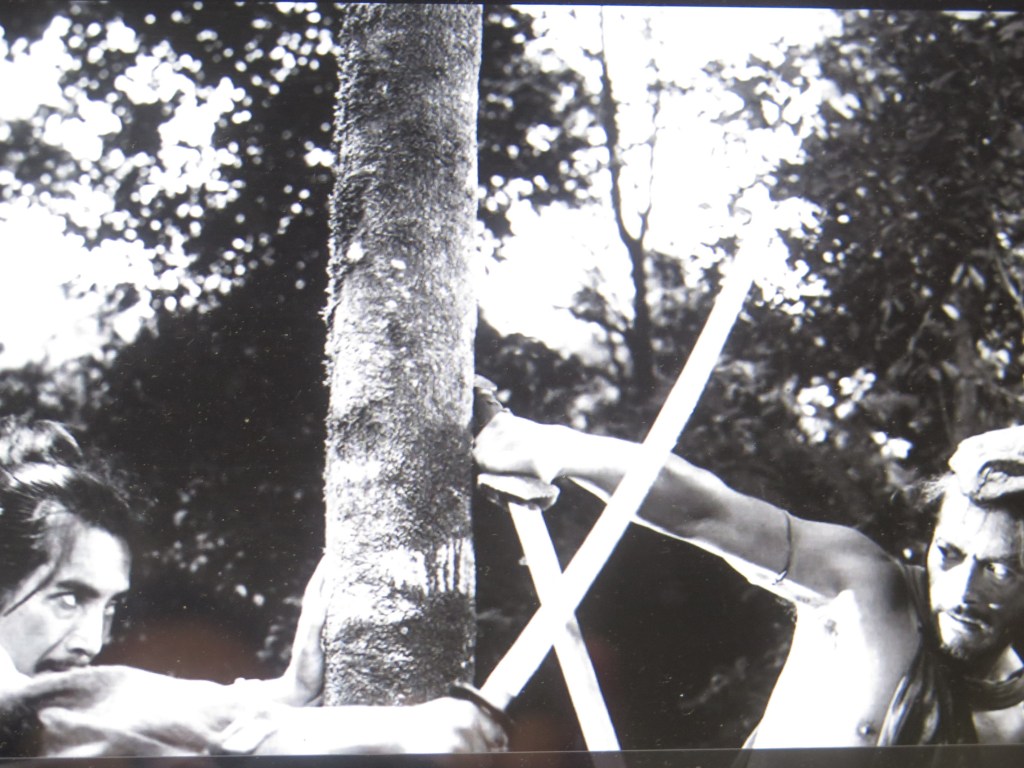

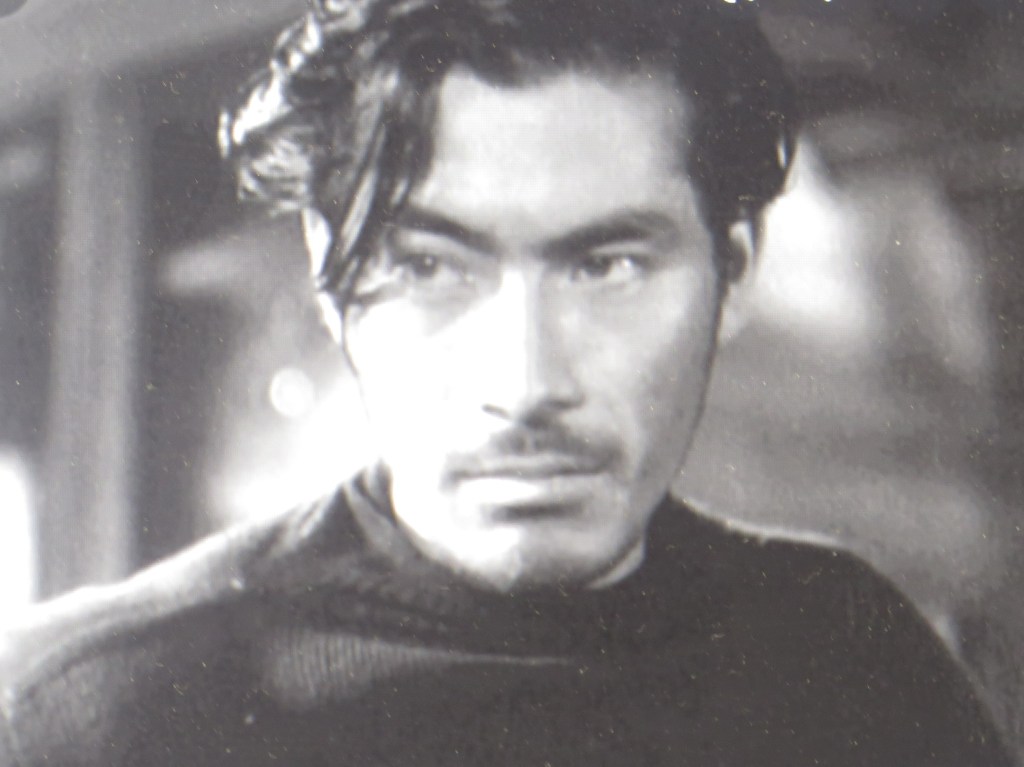

Kurosawa’s direction of the three players as the killer of the Samuri is powerful and to that their performances are sustained throughout. MIfune glares into the camera and shrieks out the story as the bandit Tajōmaru. He gleefully and wildly laughs taking pride in the murder, full of happiness that the wife (Machiko Kyō) gives herself to him on their first kiss. As he shakes and terrorizes he is brilliant and we understand how a woman might be mesmerized by his famous reputation as Tajōmaru the fierce bandit, attracted and repelled, but softened when he employs his powers of seduction. Mifune’s performance rises to the myth of Tajōmaru and electrifies as Kurasawa makes use of the straight-on camera shot of Mifune cross-legged, then close-ups of him flashing eyes and teeth to horrify and delight. No wonder this sterling performance captivated audiences globally then and now.

Likewise, as the wife Machiko Kyō is convincing and equally terrifying in her incessant weeping and wailing conveying the great harm the violation has done to her soul. Additionally, the husband’s cruelty after her rape is even more damaging emotionally for he blames her with his eyes and spurns her as the rotten goods that he will never touch again. The adaption of Boléro by Maurice Ravel by Fumio Hayasaka is as relentless as her emotional devastation and hysteria, signifying her loss of self, world of beauty, sanctity and safety. Interestingly, Kurasawa interchanges the cinematography varying it from that used with the bandit, implying the helplessness, the softness and the tragedy of the wife.

As the Woodcutter and the psychic who is wonderful relate “what happens” again Kurosawa changes up the shots and varies to close-ups except with the Samuri whom he mostly has in medium shots. However, with the psychic who is inhabited by the dead Samuri’s spirit, he uses close-up to maximum terrifying advantage.

Rashomon put Kurosawa, Mifune and the others on the global map of cinema for all time. It continually makes film lists of cinema greats. At the time it won The Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and an equivalent Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Don’t miss Rashomon or the other films at Mifune Film Forum Festival. For tickets and times go to the Film Forum website: https://filmforum.org/series/toshiro-mifune

‘Mifune Festival’ at Film Forum February 11-March 30

Part I

Mifune, a four-week festival of 33 films is celebrating the legendary Japanese actor Toshirō Mifune at Film Forum from February 11 through March 30. Co-presented by the Japan Foundation, the series features 16 of Mifune’s collaborations with iconic director Akira Kurosawa in what has been identified as one of the most seminal actor-director partnerships in film history. The duo produced some of the greatest masterpieces of world cinema. And Kurosawa’s films continually serve as an imprimatur for global directors mesmerized by Kurosawa’s cinematic storytelling. Indeed, Kurosawa once admitted that without Mifune, he would have no great films.

Postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the festival, originally titled MIFUNE 100, planned to commemorate Mifune’s centennial year in 2020; the actor was born on April 1, 1920. After two years, the decision was made to open the retrospective on the legendary actor. Film Forum Mifune Festival includes rarities and rediscoveries in 35mm imported from the libraries of The Japan Foundation and The National Film Archive of Japan. It has been programmed by Bruce Goldstein, Film Forum’s Director of Repertory Programming, and Japanese film scholar Michael Jeck.

This first in the series of articles gives an overview of select Kurasawa films that featured a young Mifune with another seminal actor Takashi Shimura, who often plays the foil to Mifune’s gruff, crude, deep-voiced characterizations. Highlights include a brief synopsis of each film and some points about the cinematography, scenic design and acting. The discussion moves in the film chronology from 1947-1949, beginning with Snow Trail (1947) Drunken Angel (1948) and Stray Dog (1949). In Part II you will find coverage for subsequent Mifune films including Rashomon (1950) which catapulted Mifune and Kurasawa to worldwide acclaim and awards and opened doors to further celebrity, dramatic risk and intriguing opportunities that historically shaped the cinematic art for decades. Film Forum Website for the MIFUNE FESTIVAL https://filmforum.org/series/toshiro-mifune

SNOW TRAIL (1947) At Film Forum: Tuesday, February 15 at 12:40, 6:00

Kurasawa casts Takashi Shimura (Nojiro) and Toshirō Mifune (Eijima) as escaped bank robbers, who with a third older accomplice retreat to the snow covered mountains to hide, though their impossible journey is besieged by one trial after another. Kurasawa configures the robbers with unique personalities and then pulls a switch when they confront the hellish conditions of traversing in six foot snow drifts along sheer mountain cliffs, and their older accomplice falls to his death taking his portion of stolen money with him. This is a wake up call for both Nojiro and Eijima and an important turning point where we empathize with these individuals as they realize the hopelessness of their situation from which they most probably will not get out alive.

All seems lost as the actors struggle against the mountain’s death grip. Kurasawa’s perfectly balanced scenic design and cinematic shots of the dominance of the mountain terrain, the deep snows, isolation and the freezing temperatures threaten their every step. As neophytes against nature’s cold, blasting fury, we see in their faces their yearning for life and sadness that it is over for them. Shimura especially gains our sympathy, but then a miracle occurs. They stumble upon a lifeline, a ski trail which eventually leads them to a resort where its hosts, a grandfather and his young granddaughter, entertain ski expert Honda (Akitake Kôno). It is there in this warm, congenial company where the fibers of the robbers’ characters are revealed and we note Kurasawa’s philosophical perspective teased in through the dialogue and emotional fear and pain of Mifune’s Eijima and Nojiro’s growing grace.

As Nojiro pulls away from Eijima, appreciating the sweetness of the little granddaughter, who reminds him of the daughter he lost, Eijima becomes more crude, violent and angry with him, attempting to dislocate his accomplice from their kindness. After all, Nojiro, masterminded the robbery, but from his icky sentimentality at the granddaughter, Eijima fears Nojiro lost his resolve to escape. It is in these scenes where we see the menace, bluster and extraordinary vitality of Mifune’s acting dynamism. How their characterizations diverge toward inner redemption and damnation as they attempt to scale the mountains after blackmailing Honda to guide them generates suspense, tension and danger. These elements heighten as Honda saves their lives repeatedly but must close down when he breaks his arm and is shot in the leg.

Mifune and Shimura are the perfect duo. Their technique and Kurasawa’s close-ups and medium shots provide the light and the dark, the hope and the desolation that propel the characters’ emotional turmoil up the mountain of fate in this survival story of good and evil that is layered, intricate and metaphysical. Against the mountain, their doom, with Kôno’s Honda bestowing the rope lifeline, symbolic of the code of community and friendship (the mountaineers code) it is up to each of them to work cooperatively to save each other from destruction. This is the lesson of redemption and hope that only one of the robbers learns and with that knowledge, gains the strength to be accountable for his actions.

Drunken Angel (1948)

At Film Forum: Saturday, February 19 at 12:40

Sunday, February 27 at 6:00

Monday, February 28 at 12:40

Tuesday, March 1 at 8:20

Wednesday, March 2 at 5:50

Thursday, March 10 at 2:45

Drunken Angel is Kurosawa’s examination of the soul’s demise to self-destruction. For this journey Kurosawa casts Takashi Shimura as the alcoholic Dr. Sanada and Mifune as Matsunaga a member of a Yakuza gang who controls the area but is evicted from his power when the boss exploits him then puts another in power until Matsunaga self-destructs. Dr. Sanada’s office is by a pond of chemicals and slime which Kurosawa sneaks in as symbolic of the entire community as the cesspool of humanity. The pond water which makes others sick, is likened to the values that make humanity sick: greed, exploitation and selfishness.

Interestingly, Sanada whose character weakness makes him a drunkard, has a kind heart and attempts to make a difference with these individuals who are worse off than he. As his patient, Matsunaga who has tuberculosis doesn’t follow his instructions, though if he did, he would be able to survive, maybe thrive. Sanada has a young female patient who he is helping to heal. However, Matsunaga lacks the will to help himself, regardless of how much Dr. Sanada badgers him not to drink and take care of himself. Clearly, Dr. Sanada puts up with Matsunaga’s manner, invests himself in the gangster attempting to help though the people who surround Matsunaga don’t care if he lives or dies and contribute to making him sicker.

Once again, Mifune’s performance as the soul destroyed gangster who Dr. Sanada sees as worthy to be helped is masterfully, carefully revealed, especially in his revelation that Matsunaga doesn’t have the energy or will to follow Sanada’s instructions, and allows himself a slow suicide. Theirs is an amazing duel of emotions: impatience, helplessness and withering bravado, frustration and love. The symbolism revealed in the scenic design of the various environments and the shot compositions of the dance hall, Dr. Sanada’s tight office, the close-ups of the emotional weariness of Mifune’s Matsunaga and the frustration and anger of Shumira’s doctor is superb. Despite the soul filth of the criminals who oppress, theirs is a relationship that appears noble. Sanada’ concern for Matsunaga leads us to feel empathy that he is dying, caught in his own sorrowful web of sickness and destruction that he let into his spirit when he gravitated toward the criminals in the hope of being “someone” others might respect. It is Matsunaga’s tragedy and the tragedy of all the self-annihilating criminal class, the theme of this superb film.

Stray Dog (1949)

Monday, February 14 at 8:10

Friday, February 18 at 2:40

Sunday, February 20 at 12:40

Thursday, February 24 at 5:50

Wednesday, March 9 at 8:10

Stray Dog is Japan’s first film noir crime procedural influenced by Jules Dassin’s script of The Naked City with Kurosawa’s signature philosophical commentary on the nature of the human soul in its travails through post-war Tokyo and beyond. Kurosawa sets the action in some of the most rubble-strewn sections of Tokyo in a clothes drenching heat wave before air conditioning cooled and refreshed. In every scene the pressure and struggle is evident in the scenic design and cinematography of the gritty, torn up city where vets, finding little work, join the Yakuza (gangster network).

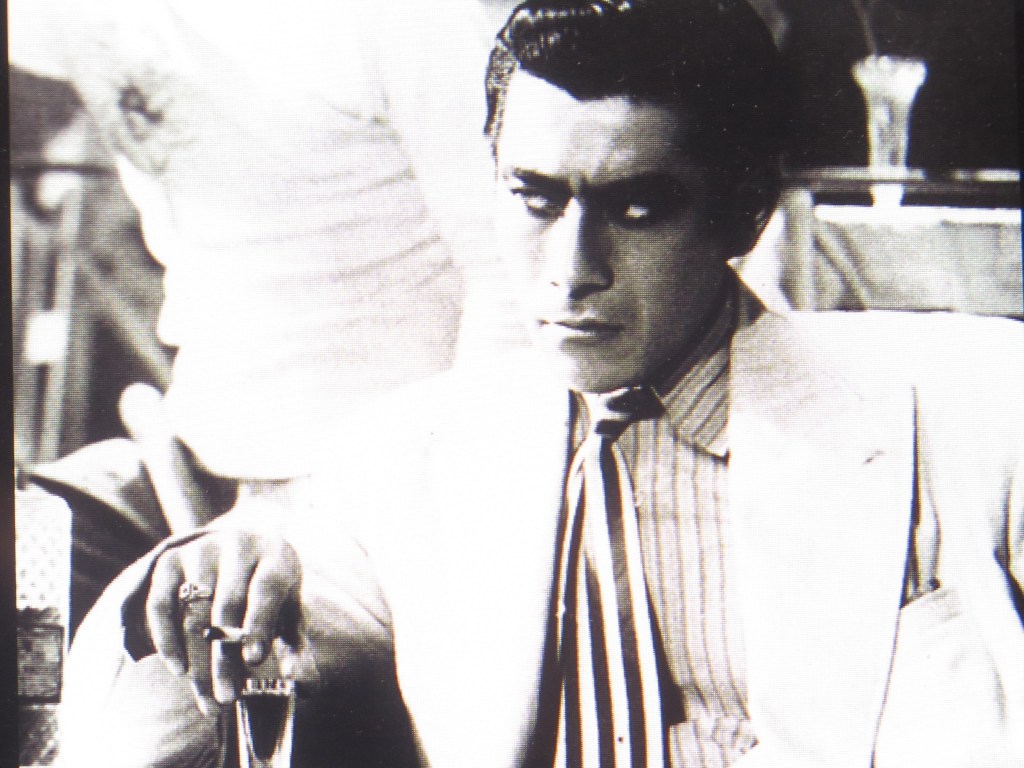

Every character, every actor especially leads Takashi Shimura as Detective Satō, and Toshirō Mifune in an uncharacteristic but athletic portrayal as Detective Murakami, Kurosawa features with close-ups, dripping perspiration tear-drops down noses, chins and foreheads. White suits, dresses and hats show huge swaths of white cloth darkened with dingy, messy, wet stains. The heat Kurosawa uses as a character. And as a symbol, it represents the pressure and tension that Murakami (Mifune) puts himself under, obsessed with guilt that he isn’t up to the task of being a competent detective.

The driving incident occurs when neophyte Murakami, white suited and new to the job, has his Colt-45 pick pocketed while jostling against other sweltering passengers on a crowded streetcar. Realizing who stole it, Murakami charges after the thief on foot but eventually loses him. Thus, set in motion is the race against time to locate the stolen weapon. Murakami, who is shy and quiet with other detectives in the department, is ready to resign when he realizes that the gun was used to commit murder. His upright, honest and sincere attitude (fascinating to see Mifune’s humble versatility in comparison to previous criminal roles) is appreciated by the department head who assigns him to work with seasoned detective Satō (Shimura).

Together as a disparate but cooperative and congenial team they piece together the clues to those who can be traced through to the girlfriend (in an ironic, dramatic scene with her mother) of Yusa who commits two murders with the Colt-45. Look for the famous nearly 10-minute sequence shot by hidden camera in the city’s toughest black market as Mifune’s Murakami goes undercover to buy a gun on the black market and reveals the palpable anxiety and frustration at coming up against dead end after dead end. The taut thriller emotionally magnifies for Mifune’s Murakami, when Satō is almost fatally injured. Mifune is so authentic as he goes to pieces believing his gun killed his mentor and friend. Also, catch the superb dialogue at the conclusion when Satō encourages Murakami not to feel badly for Yusa. Shimura’s comment is eloquent, philosophical and pointed and Mifune’s response is memorable.

The schedule of films beginning the series on Friday, February 11th is as follows or go to the Film Forum website: https://filmforum.org/series/toshiro-mifune

RASHOMON (1950)

Friday, February 11 at 2:55, 7:10

Wednesday, February 15 at 5:35

Friday, March 4 at 3:50

Saturday, March 5 at 12:40

Wednesday, March 9 at 6:00

Thursday, March 10 at 12:40, 5:10

I LIVE IN FEAR (1955)

Friday, February 11 at 12:40, 4:55, 9:10

Friday, February 18 at 12:30

Saturday, February 19 at 2:50

Sundance Award Winner: ‘Hive,’ 94th Oscars® Shortlisted for Best International Feature

Hive, a triple award-winner at Sundance Film Festival is a beautifully constructed, exceptionally acted and poignantly rendered feature film by writer/director Blerta Basholli. In the film, Basholli simplistically and profoundly examines the aftereffects of the 1998-1999 Kosovo war that impacted civilians and dislocated the cultural mores and society of Kosovo.

It is through this backdrop that Basholli focuses on representative families that suffered the loss of relatives and economic hardship which was felt greatest in the towns where killing, rape, burning and looting took place. One of the largest massacres happened in the village of Krusha e Madhe, the setting of the film inspired by a true story. There, families are still waiting over twenty years later for word of their loved ones in the hope of recovering their clothing or bodies so they might receive a proper burial. Then, the uncertainty of what happened to their husbands and relatives would finally reach closure.

Writer/director Blerta Basholli reveals the strength and resilience of the women whose husbands have gone missing as they attempt to confront their grief, raise their children, take care of their in-laws and put food on the table with their own ingenuity, hard work and home crafted items. Focusing on Fahrije Hoti, Basholli reveals how the enterprising Hoti gradually fights the patriarchal culture of lazy men to gather a collective (a hive) and establish a way for the women to support themselves and their children, launching a business to make and sell ajvar (roasted red pepper spread).

Initially, we see that Hoti attempts to maintain her husband’s bee hives, collecting the honey and having her father-in-law who is in a wheelchair sell it. During the film we learn the bee hives and honey are a remembrance of her husband, though the honey doesn’t provide them with enough money after it’s sold. And she hasn’t found the way to deal with the bees like her husband did, so that she doesn’t get stung. Hoti ends up having to nurse her wounds as the bees sting her when she gets the honey.

As Fahrije Hoti, Albanian actor Yllka Gashi teases out an exceptional portrayal of the woman whose struggles inspired the director to create her story from emotional truth. When a car is donated so that Hoti can drive and help the other widows, she gets a license. And because she and the women are destitute, she gets the idea to start a business selling avjar. But the men of the village reject her driving autonomy and her flitting around the village to pursue business. It is a threat to their masculinity and power structure extent for centuries.

When she parks near the cafe to do business, a rock is thrown smashing the car window. Her transgression is clear. Their violent attack forewarns her to stop or worse will follow. However, Hoti doesn’t respond, except to drive home and tape up the back window. She stoically continues about her business without confronting the men at the cafe who despise her.

As Hoti is encouraged by another, older widow, despite the disdain of even her own children and her father-in-law who disagree with her plans, gradually, she and a few women agree to form the business. They chip in money for the supplies. Eventually, they meet at her house to make the avjar. However, she faces tremendous backlash and her own daughter is nasty to her when Hoti attempts to sell a band saw, a memento of her husband to get the money to buy more peppers.

Other obstacles come from the men in the village whose chauvinistic egos are threatened by these autonomous women. They try to destroy their product and stop their sales. Clearly, the men see them as whores who have overstepped the boundaries of the female identity set in the traditions of the town. And the man who sells her the red peppers attempts to collect payment in sex, assuming that she is a whore, for what woman would do what she is doing?

One of the important conflicts in the film, explores Hoti forging ahead despite ancient mores and folkways that would keep her and her family starving. She, like the other women widowers, is destitute. However, where the other widowers are afraid, Hoti has nothing left to lose. Hoti’s ability to drive strengthens her; one taboo has been overthrown. Why not be the head of a business? Another taboo is overthrown. Initially, the other cowed women reject her plan to sell their product out of fear of censure and a reputation of disgrace.

But with every move she makes, Hoti becomes more determined and she exemplifies to the others that the archaic folkways make no sense in a modern world. The irony is that the complaining, bullying men condemn them for working but do not lift a finger to support them. They approve of their groveling in starvation, another type of ignominy, without their husbands. Either way, the women are disgraced for they are women without men. Hoti and the women defy the men’s backward definitions of who women are. They redefine themselves.

Cleverly, the director subtly shows the harmful misogyny as a destructive nihilistic force which benefits no one, least of all the entire town. Basholli presents this as she tells the story through silences and actions, without haranguing or presenting a political argument. The effect is striking; we feel the full force of the crumbling of the patriarchy as the men fear having to redefine themselves, which these powerful women are forcing them to do.

Basholli’s themes are striking. It is clear that the lazy men begrudge the women’s attempt to survive without their husbands. In other words they are to remain stuck in time with no identity, power, autonomy, sovereignty apart from their husbands. They are expected to curl up and die as an honorable way to remember their men; be with them in death or wait in limbo in a dead zone. The thought that the widowers make a life for themselves to overthrow the former traditions is the death of the old way and the beginning of a new way that Hoti is creating. She chooses hope and life after the massacre of the village. Hers is a bold, vibrant, maverick move. Astounding and revolutionary, she re-emerges a new individual.

Life and hope respond in renewal as the women receive sustenance from each other and appreciate their new unity, inner peace and financial power from their “hive.” Thus, they continue to contract with other supermarket owners who sell what they are making and expand, as the director shows after the last cinematic shots of Gashi. At the conclusion, Yllka Gashi as Hoti is dressed in a beekeeper’s outfit. A bee walks on her hand as she remains at peace, unafraid, knowing the bee will not sting her, like her husband never was stung. Basholli renders Hoti’s metaphoric, symbolic peace in communion with the bee as acceptance of the opportunity and new world that she recognizes is open to her.

This superb debut feature film by Basholli is Kosovo’s official selection for Best International Feature Film, Kosovo’s eighth official entry, and was recently included on the International Feature Film shortlist for the 94th Academy Awards®. Hive is one to see for its dynamic award-winning performance by Yllka Gashi, award winning directing/writing and its current, vital themes about defining one’s life, and persistence in carving out one’s place, especially in a society that is closed, weak and crumbling.

DIGITAL / VOD RELEASE – FEBRUARY 1, 2022

Available on all major digital/VOD platforms including:

Amazon, Apple TV, Google Play, Kino Now, Vudu, and

The Criterion Channel (starting February 8th)

Lincoln Center Film, Joachim Trier: ‘The Oslo Trilogy’

Norwegian Film Director Joachim Trier is being celebrated at Lincoln Center Film for his most recent film, The Worst Person in the World, which screened at the NYFF 2021. This is the third film in his collection, The Oslo Trilogy, which includes Reprise (2006) and Oslo, August 31st (2011) all of which feature the superb Anders Danielsen Lie who interestingly is a practicing physician and an actor. The Trilogy screenings on select dates will be followed by Q and As by Joachim Trier, Anders Danielsen Lie, and Renate Reinsve (The Worst Person in the World) and Joachim Trier and Anders Danielsen Lie for Reprise and Oslo August 31st. Click for tickets here. https://www.filmlinc.org/daily/the-oslo-trilogy-with-joachim-trier-and-renate-reinsve-in-person-begins-jan-28/

The title of the collection of films centers around the city where Joachim Trier was born and grew up. The setting of each of the films reflects upon sections of Oslo, Norway that Trier revisits and encapsulates while he integrates his various story arcs in each film, whose themes interlock and concern ambition, dreams, identity, loss, satisfaction memory, isolation.

Reprise captures the society of twenty-something friends from Oslo as they plan their lives and attempt to actualize their dreams. Trier separates out two budding writers, Erik (Espen Klouman Høiner) and Phillip (Anders Danielsen Lie) and places them under a microscope, allowing them partial successes, and ups and downs as they move along divergent paths with one ending up nearly taking is life, though his novel has achieved a modicum of success. As Erik attempts to help Phillip get back on his feet and regain a love relationship which was broken off, he confronts his doubts about his writing attempts. We watch the unfolding of their uncertainties, depressions and the excitement and hope of a satisfying writing career.

In Reprise, memory and fantasy merge in the comedy-drama that is playful and whimsically hopeful. As the writer’s imagination takes over Erik, we understand that he may achieve a possibility of success. Of course, the irony is that Phillip has achieved writing success, but it isn’t enough for him; returning to a former love is what matters. Thus, achieving their out-of-reach dreams remains different for both friends. And it is only through Erik’s imagination that they manifest the goals that make them happy.

The tone of Reprise turns darker and the comedy becomes muted in the award winning Oslo, August 31st which is loosely based on Pierre Eugène Drieu La Rochelle’s novel Will O’ the Wisp. This second film of the Oslo Trilogy is also written by Eskil Vogt and Joachim Trier and examines the interior soul psychology of the life of a recovering drug addict. When the film opens, Trier cleverly introduces us to Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie) without a hint of his enslavement to his former addiction when he walks to a river and attempts suicide unsuccessfully. From then on we understand the stakes and question how and why he has arrived on the brink of death only to eschew it. Trier keeps us in a state of tension as to whether Anders has given up or plans to try again.

From this initial uncertainty of details about where he has come from (the woman he slept with) and how he arrives at the beautiful house where they seem to know him when he walks in the door, we learn that Anders is in a rehab center. During his group therapy session, we learn he had a severe drug addiction and emotionally, he tells the group that he has been stable. This information collides with the previous scene; it is obvious he is lying and in group therapy, he has not dealt with the interior pain of his emotions or psyche.

Nevertheless, on August 30 Anders is journeying on a new road in his life as the therapist discusses the job interview which has been set up for him, though he is not enthusiastic about it. Then, as he takes off for the interview he makes a number of stops along the way, during which time he will see his sister and visit his home which his parents are selling to pay for his rehab.

It is on this journey, we discover he is in touch with his inner self. The darkness within is confirmed when he visits and confesses to close friend Thomas (Hans Olav Brenner) that he finds little purpose to his life and that he doesn’t think he ever loved his former girlfriend Malin, whose bed he leaves then tries to kill himself. In his discussion with Thomas, he even confesses that he doubts his love of Iselin with whom he had a long relationship and a rocky breaking off. The irony is that he is clean. The rehabilitation worked to settle him away from addiction, but it didn’t help him fill the cavernous soul abyss which overwhelms him in the thought that he has no reason to live. It becomes obvious that he used drugs to deaden the pain and ferry him away to a land of oblivion.

Ironically, when he confides to Thomas that he is suicidal, Thomas confesses that he is not happy in his life; that he has stopped finding passion with his wife and that he is going through the motions of living and raising kids. As they confess their trials to each other, they achieve a greater closeness, but that doesn’t assure Thomas that Anders won’t take his life. Thomas makes Anders promise he won’t commit suicide, and Anders obliges his friend. Nevertheless, because we have seen Anders’ suicide attempt at the top of the film, we are not convinced that he won’t try to end the meaninglessness of his life and pain of living.

Trier presents Anders’ soul/psyche condition in a series of worsening failures, spiraling him and us further into the black hole toward death. The journey on his leave from rehab takes him to his unsuccessful job interview, his failed meeting with his sister Nina, a party where he waits for Thomas who doesn’t show, to a drink after months of no alcohol, to a bar with old friends and more drinks, to a return to his old haunt at his dealer where he scores a large batch of drugs. On August 31st, when he reaches his parents’ home that is in disarray for Anders’ sake, being packed up for sale to save Anders’ life, the inevitable occurs.

Trier’s cinematography won a well-deserved award and the acting by Anders Danielsen Lie is heartfelt, profound and emotionally driven with a low key beauty and sensitivity, beautifully shepherded by Trier’s direction which is wonderful as is the editing. There is just enough cinematic silence and imagery to draw us in and keep us engaged with Anders’ journey, as we are being led emotionally, invested in Anders’ survival. This is one to see and is the explanation of another reflection of Oslo, Norway at a time when Oxycotin and heroin had been ravaging global culture.

The Worst Person in the World is a dark romantic comedy-drama that chronicles four years in the life of Julie (Renate Reinsve). Like with Trier’s other two films, the protagonist is a young, in this focus, a woman looking for her own autonomy and identity as she negotiates the deep and roiling subterranean channels of her love life. Facing uncertainty with her career path and struggling to gain stability and balance, she eventually attempts to view herself realistically and authentically, despite her desire to avoid looking in the mirror.

Once again Joachim Trier hits is out of the park and like in Oslo, August 31st, The Worst Person in the World is a multi-award winner. Renate Reinsve is devastatingly brilliant and translates an authentic performance into a beloved, flawed human and believable woman.

Don’t miss this marvelous triumvirate of great films by Joachim Trier and the Q and As with the director and lead actors by first reserving seats and purchasing tickets at https://www.filmlinc.org/press/flc-announces-joachim-trier-the-oslo-trilogy-january-28-february-3/

New York Jewish FF: ‘The Lost Film of Nuremberg’ and ‘From Where They Stood’

Two documentaries, screening at the New York Jewish FF are must-see viewing. Both have as their subject the recording of photographic evidence of the Shoah, the Holocaust (the mass murder of Jewish people under the German Nazi regime during the period 1941–45). Considering the rise of white supremacist hate groups encouraged by the former U.S. president, these films provide an important record. Since World War II though the Holocaust has been much written about and over the decades has been the subject of movies, films, articles and plays, the Nazi atrocities in concentration camps throughout Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy and other countries, increasingly have been called into question by global Holocaust deniers.

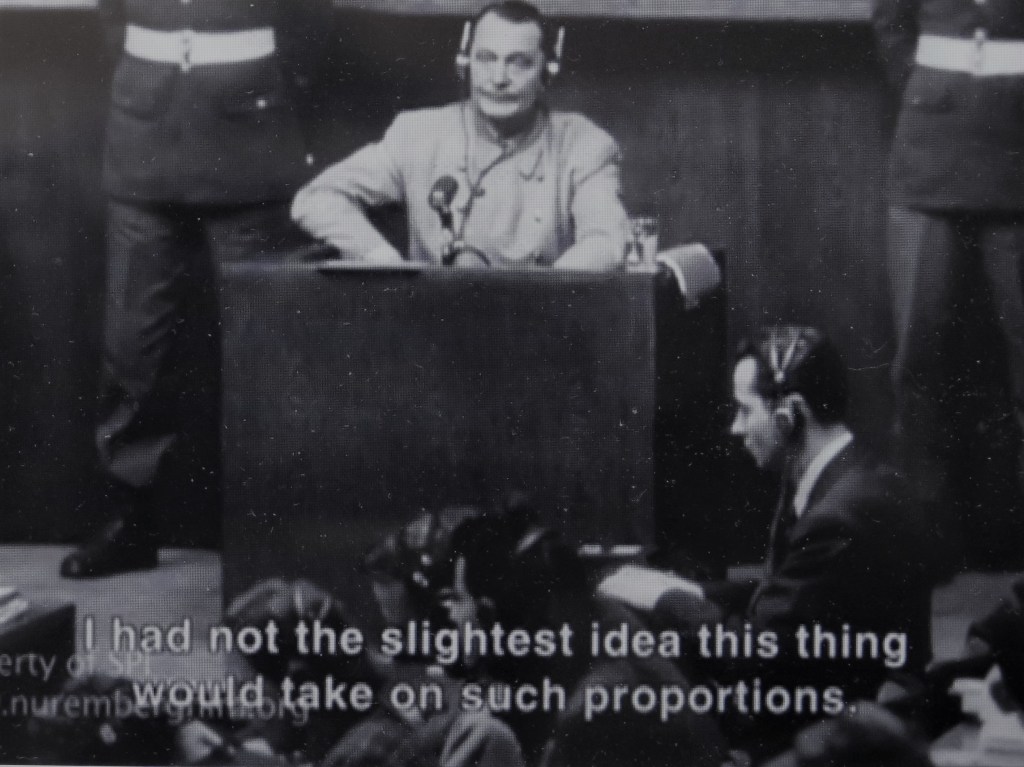

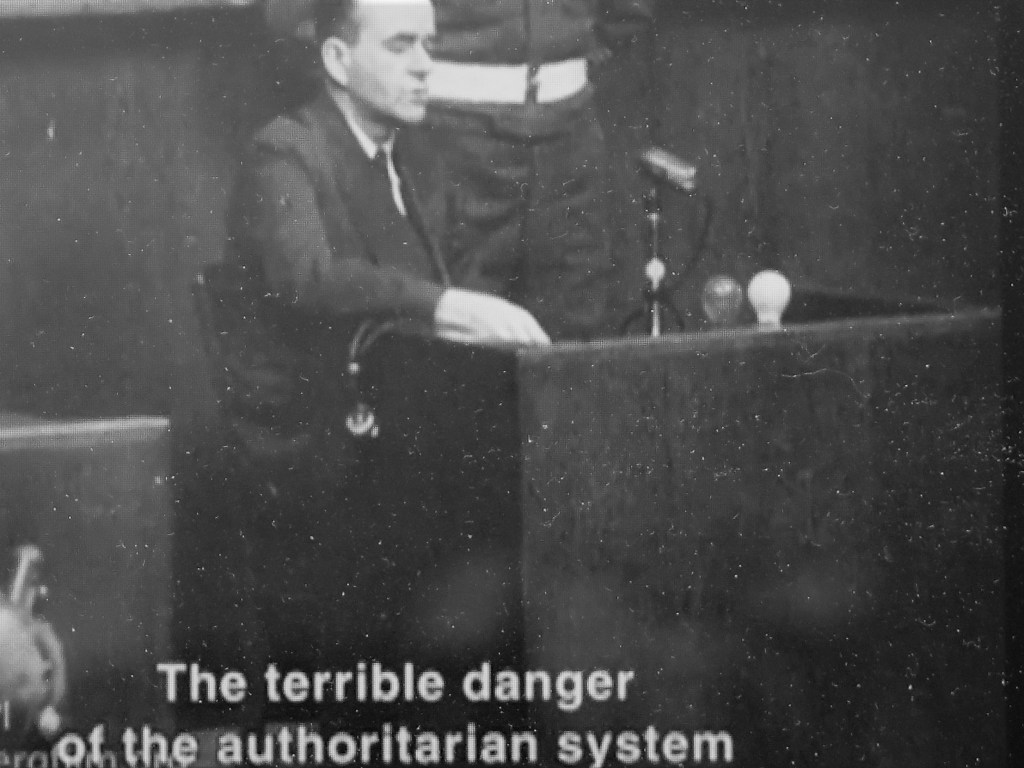

The Lost Film of Nuremberg chronicles how veterans of the OSS War Crimes Unit, brothers Bud and Stuart Schulberg (Hollywood filmmakers under the command of OSS film chief John Ford) endured obstacles and setbacks on their mission to track down and collect film evidence of Nazi war crimes to be used at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Their work was vital if done assiduously, for it would be used to judge the war crimes of high ranking Nazi officials like Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Albert Speer, Rudolf Hess, Alfred Rosenberg and others, and punish them if found guilty.

The Schulberg’s collection of Nazi films was used with testimony, documentation and the filmed proceedings of the Nuremberg trials to create Nuremberg: Its Lesson For Today. Thus, The Lost Film of Nuremberg shows the discoveries and angst the Schulbergs went through to create the superb pro-democracy film Nuremberg: Its Lesson For Today. It was released in 1948 throughout Germany, but it was never seen in the United States until a decade ago. Indeed, for over sixty years it had been “lost.”

Director/writer Christoph Klotz adapts daughter Sandra Schulberg’s monoaph, Filmmakers for the Prosecution to make The Lost Film of Nuremberg a stirring and exciting revelation about a chaotic period of time after WW II. Klotz includes tidbits from Schulberg’s perspective in letters to his wife. This material is provided by daughter Sandra. What makes the film more intriguing is the inclusion of Sandra’s perspective of her father and this commission which she only discovered after her mom died and she was cleaning out their home.

Klotz uses flashback liberally with narration by Sarah-Jane Sauvegrain to tie in the past and the present. Thus, we see clips of the youthful brothers examining Nazi film they’ve received. We hear/see Stuart’s letters to his wife detailing the journey to Germany and his impressions the to find films that the Nazis themselves produced. Stuart (the youngest member of the OSS Team) and brother Bud learned early on that the film they were making must be a compilation of actual films recording the words and deeds of the defendants. Thus, the incriminating films would be used to convict them.

Sandra learns salient details why her Dad’s “lost Nuremberg film,” edited and finalized in 1948 was created. It was to be shown in Germany and Europe for educational purposes. The intent was for the de-Nazification of the attitudes and mores of citizens after the war. It was also to show the difference between Allied Justice leveled against those committing crimes against humanity and Nazi Justice which was no justice if you were not a member of the Third Reich. Sandra’s eyes were opened to another side of her father’s vital work, for surely though it didn’t receive public release, other filmmakers knew of it and the archival Nazi films used to make it. These provided the linchpin around which subsequent films about the Holocaust would be made.

Klotz adds rare, never-before-seen footage, and reveals why the film was never released in the United States. Also, he includes Sandra’s reflections about what her father must have felt upon seeing the horrors of the camps as a young man. Klotz includes commentary of the older, retired Bud Schulberg giving a lecture about the subject of the film and why the Nazis made incriminating films of disturbing and horrific images. However, other films and Nazi evidence, buildings and documents were destroyed. The Nazis intended to escape justice, which many did, leaving Germany for the US, South America and other safe havens.

In The Lost Film of Nuremberg, Klotz relates the story of how German film director Lennie Riefenstahl was arrested and became a witness for the prosecution. Her propaganda film Triumph of the Will was created for Hitler’s use. The film identified various Nazi officials at Hitler rallies and it also evidenced Hitler’s plans. Another helpful individual was Hitler’s personal photographer Heinrich Hoffman, who had 12,000 negatives they used, after he was picked up, arrested and questioned.

As a result of the film evidence, the 19 out of 22 high ranking members of the Third Reich at Nuremberg were found guilty. Only three were acquitted. The other19 were either executed (Göring committed suicide) or received life or lesser sentences for committing crimes against humanity.

The Lost Film of Nuremberg is screening at 1 pm and 7 pm on 13 January at Lincoln Center, the Walter Reade Theater. Q & As with the director and producer Sandra Schulberg are also on that date. For tickets go to https://www.filmlinc.org/films/the-lost-film-of-nuremberg/

From Where They Stood is French documentarian Christophe Cognet’s unadorned and acute investigation of rare secret photos taken by prisoners in various concentration camps at great risk to their lives. They did this in the hope of documenting the atrocities they witnessed from spring 1943 to the fall of 1944. Examining the negatives carefully with a magnifying glass, Cognet visits the camps where the prisoners took the film and then either buried it to dig it up later or sent it out in a package. Some negatives came with a description that was revealed after the liberation of the prisoners who then wrote down the information. Other photos are of portraits of prisoners with no explanation or names sitting against the barracks. Others are of crematoria.

Many of the photos elucidate and confirm life and atrocities in various camps: Dachau, Buchenwald, Mittelbau-Dora, Ravensbrück, Auschwitz-Birkenau. With a translator, Cognet visits the camps and adjusts the photo negatives so that the viewer can see how the photo depicts what the location looked like. Verified are crematories, burn pits where bodies were disintegrated as much as possible. Interestingly, the bone fragments are present to this day, leaving a record of the great crimes of murder. The bone fragments to the surface after a heavy rainfall.

Unlike The Lost Film of Nuremberg, there is no music or narration or attempt to thread the places together. We hear just the silence of footsteps crunching against the walkways and the sound of birds chirping in the background. The simplicity is haunting and one realizes one is viewing a graveyard where many innocents suffered because they were considered enemies of the Third Reich.

Cognet also includes negatives which document Sonderkommandos (usually Jewish prisoners who pulled out the naked bodies from the gas chambers and piled them on carts taking them to the crematories) stand in front of a massive pile of bodies to dispose of and burn. Additionally, women who had been used for experiments (referred to as rabbits) also pose for the camera showing the areas of their body where they’ve been experimented on. Reference is made to one experiment: a gash is made and gas gangrene is encouraged by injecting a bacillus into the site. The wound is left untreated to see the progress of the gangrene.

Because Cognet uses straight cinema verite style, the effect of the prisoners’ photographs of the past paralleled with the locations of those places in the camps in the present is stark and shocking. The posting of the enlarged negatives at the location allows the viewer to see what the prisoner saw, to stand in his or her shoes. Indeed, it leaves one numb to consider the risk these individuals, took to sneak out the film to document what was going on so the world would know. For this film Cognet’s minimalism to just see what is in the photograph is remarkable.

From Where They Stood is screening virtually from 14-19 January. For tickets go to https://www.filmlinc.org/films/from-where-they-stood/

The Lost Film of Nuremberg is screening at 1 pm and 7 pm on 13 January at Lincoln Center, the Walter Reade Theater. Q & As with the director and producer Sandra Schulberg are also on that date. For tickets go to https://www.filmlinc.org/films/the-lost-film-of-nuremberg/

New York Jewish FF 2022: ‘Sin La Habana’ review

Sin La Habana, the award winning narrative feature, exceptionally written and directed by Kaveh Nabatian, who also wrote the original music, is a beautifully layered film that completely engages from the opening shot to the uncertain ending. Sin La Habana is enjoying its New York premiere as the Centerpiece film at the New York Jewish Film Festival 2022. The NYJFF 2022 is being presented live and virtually from January 12-25, 2022. For tickets and scheduling see the last paragraph of this review.

The haunting, profound, poetic cinematography by Juan Pablo Ramirez, and the acutely thoughtful editing by Sophie Leblond intrigues us to the story arc of a Cuban ballet dancer and his lawyer girlfriend who loathe La Habana, Cuba. The city of Havana (in Spanish Habana) holds little promise for them, amidst the broken down buildings, squalid impoverished settings and lack of progress evidenced from Fidel Castro’s dictatorship and the decades long U.S. embargo. Leo and Sara envision a better life for themselves elsewhere, but their first world destination country in a time of global immigration restrictions leaves their only route of escape to be marriage to foreigners.

Leonardo (the excellent ballet dancer/actor Yonah Acosta Gonzalez) is the best dancer in the company where he performs, but he can’t catc,h a break for the star role as Romeo because of his “lack of humility,” says the director of the company whom he accuses of racism, and who fires him after he curses the director out. His girlfriend Sara, who is a daughter of Orisha (both Leo and Sara are practitioners of the West African religion of Babalawo which in Cuba resembles Santeria or Vodun) is as ambitious as Leo. Their high expectations and confidence in themselves lead them away from La Habana to achieve material success and new identities, though it will mean leaving their cultural heritage back in La Habana. Their decision is filled with risks, isolation and heartbreak; but with each other, they believe new possibilities are at their fingertips with their talents and skills.

We note that throughout Sin La Habana, Leo always prays and keeps in touch with his faith, practicing it as best he can through his memory when he lives in Canada, “without the influences of La Habana,” the music of the ceremonies, the rituals and the divination which at the beginning of the film he relies upon for guidance. Through flashbacks of Leo’s religious practice in La Habana, Nabatian reveals the importance of Leo’s faith every time he endures a setback on the journey to his dreams. To maintain the connection to hope, he has endowed an object of his goals, a beautiful, crystal clear, large marble as a symbol of affirmation that his dreams will come true.

Inspired and persuaded by Sara, Leo works their plan to leave La Habana by sparking the interest of Nasim (the Iranian Canadian Aki Yaghoubi) during his Salsa dance classes for tourists at a Parador (house in La Habana set up for the tourist trade). Leo looks for wisdom from his previous divination sessions with the Babalawo priests and strikes out for a relationship with Nasim, whom he keeps in touch with after she returns to Montreal, Canada.

Though Leo is not particularly interested in Sara’s plan to continue the seduction and marriage to Nasim, he communicates to Nasim even writing down the words Sara tells him that will touch Nasim’s heart. Sara’s words do encourage Nasim. She pays for Leo’s way to Montreal and his expenses until he can find a job with a ballet company. They live together in a house of Nasim’s friend which she has agreed to stay in and watch over while her friend is away. Eventually, Leo discovers Nasim’s backstory; she, too, is an artist; however, he remains unaware of her secret plan for her life.

As Leo and Nasim become closer, he tries to maintain his connection with Sara and his religion but it is difficult and Nasim is opposed to him practicing it, though she says it’s because he can’t mess anything up in the house of her friend. While Sara waits for him to earn enough money to send for her, she fears he will disappear in Montreal into a new life with his new girlfriend Nasim. Leo’s fortune changes and he experiences a setback after he bombs out of dance auditions, first with a ballet company, then with a maverick, new wave dance company. At a club with Nasim, he meets a fellow Cuban who hooks him up with a job and a plan to bring over Sara by marrying her off.

At this point complications arise and the risk that both Sara and Leo take intensifies. Leo meets up with Nasim’s parents and runs into racist attitudes from Nasim’s father who is disappointed that his daughter didn’t stay with her X husband who she divorced because he abused her. Nasim seeks another life away from the strict upbringing of her parents and the types of potential husbands that she would meet at the synagogue. Not only is Leo exciting, he is the epitome of the opposite of her former husband; her rebellion pleases her and she intends to make that rebellion permanent, unbeknownst to Leo, her parents and her siblings.

Meanwhile, Sara, marries Julio (Leo’s friend) and goes to Montreal. Leo and Sara see each other. Upset by Leo’s long time away from the house, Nasim turns detective and discovers Leo’s mail exchanges to Sara. Through Nasim’s expert detective work she discovers Sara is in Montreal. Meanwhile, Leo has lost his symbolic dream token, his pure marble which signifies that perhaps he has subverted his culture, his dream and the individual he wishes to be via his faith. All three stand on a precipice with no way forward except to plunge into uncertainty stoked by each other who they eventually must confront.

Nabatian’s screenplay realized through Ramirez’s cinematic ingenuity and Le Blond’s editing of close-ups, blurred montages of color, black and white shots of Leo dancing solo, contrasted with closeups of each of the characters provide an ethereal connection with this cultural world we are not familiar with. The director’s vision is fascinating, beautiful and surreal, as he reflects the minds of the individuals, especially Leo’s struggles at defining himself in place and time. The director also gradually reveals the plots of each of the individuals separate and apart from each other. Highlighting their perspectives and relationship to each other, the result is always surprising along the arc of each of the character’s developments.

The music throughout is lyrical, the rituals of Babalawo are rhythmic and the dance scenes are engaging. All of these musical and ritualistic scenes contrasted with the classical ballet add to the haunting portraits of Sara, Leo and Nasim who pursue their own journeys. We empathize with the paths Leo and Sara have chosen as they try to settle far from La Habana, carried by their hopes and memories. Likewise, the scene where Nasim is at her sister’ son’s Briss is revelatory; we empathize with Nasim’s plight as she must deal with her father’s viewpoint of her divorce and present partner, Leo. The characters’ journeys are wonderfully manifested by the performances, the cinematic compositions of each frame, the editing, music, overall design, all with a nod to Nabatian’s direction.

Nabatian’s artistry coupled with the talented crafting by Ramirez and Leblond and the actors’ heart-felt performances create a memorable film deserving of it awards. It is being shown in person at the Walter Reade Theater (165 West 65th St.) at Lincoln Center, Monday, January 17, 4:00pm. This is definitely a must see. For tickets and scheduling to the New York Jewish Film Festival go to their website at: https://www.filmlinc.org/festivals/new-york-jewish-film-festival/

‘F@ck This Job’ Award-winning Film at DOCNYC, Review

One of the most important films in the DOC NYC Festival 2021 (November 10-18) (https://www.docnyc.net/2021-festival/) is F@ck This Job. Thematically, the film concerns the press and media speaking truth to power in totalitarian countries which censor the facts so that the ruling regimes can maintain control while they grift their countries of billions of dollars. Journalists must decide if they should allow themselves to be silenced. They must decide whether or not to fight to represent the truth to the nations’ citizens, thereby risking their careers and lives. In the end one asks is it worth it to be a hero no one recognizes or cares about? But sometimes people do care and sometimes, one can make an incredible difference, though that was not their initial intention. F@ck This Job is both an inspiration and a cautionary tale for journalists everywhere, especially in countries touting themselves as democracies.

Director Vera Krichevskaya chronicles Russia from Medvedev’s presidency to Putin’s changing the Russian constitution (2018) to maintain power until 2036, something he swore he would never do. Simultaneously, the director reveals in tandem the parallel story of Natasha Sindeeva, a former music radio producer who looks to upgrade to a media manager and owner of a TV station, after she marries the rich banker Sasha who bankrolls her.

As the film opens in 2008, Krichevskaya, who has direct access to Natasha and Sasha as a friend and also a participant in their TV venture, intercuts the beautiful opulent wedding of Natasha and Sasha and the happiness of Medvedev’s election for Russians in what was then a thriving nation. All is bright pink and as rosy as Natasha’s pink Porsche, that zips happily around the streets of Moscow. In its brilliance, as the film melds two stories we understand the near cinema verité unveiling of an incredible history of a decade of events in Russia. One story mirrors the Russian citizens’ initial belief in a bright future with Medvedev. It is a vision which turns to dust as Russians realize that Putin is holding the reins of power from the shadows and is increasing his repression against journalists, Ukrainians, opposition leaders, protestors and anyone who stands against his grifting and accumulation of power and wealth at the expense of Russia’s prosperity.

Likewise, Natasha’s bright beginnings founding her TV station, the independent TVRain (Dozhd) media outlet hits a turning point. Her vision to create independent, light, glamorous media, since she had come from such an elegant universe as a music producer becomes swamped. Ironically, she labels the TV station the Optimistic Channel to signify Russia’s bright, rosy future and to forecast her skyrocketing success. But her notions upend when serendipitously, “Optimistic Channel” Dozhd TV, becomes the foremost truth-telling station in all of Russia, and a danger to Putin and his underlings at the United Russia Party.

In her yearning to “be different” and current and “independent,” Natasha goes “against the grain.” She hires opposition reporters, minorities and LGBTQ journalists who are unique and fearsome. As a result, the audience loves the Optimistic Channel because they are not “afraid” of the truth. The station has many followers. Their “in the moment reporters” do “live feeds” of devastation, i.e. of the Ukraine war, of clashes of protestors and the police, of upheavals that reveal in real time Putin’s decline in popularity. No state media channel or any media channel for that matter covers such events which global news then picks up. The bright rosy future of Russia is indeed in the toilet. The oppressors then turn against Dozhd TV to make it impossible for them to cover their stories on the air or to criticize Putin’s regime via interviews with Alexander Navalny, Putin’s chief opposition leader that Russians support.

Natasha’s life’s work becomes her daily obsession for success as the only place where Russians can go to experience political and sexual freedom as an independent news station beyond Putin’s control. For example, during this unprecedented decade of modern Russian history of Putin’s growing oppression, Dozhd covers the war in the Ukraine, Navalny’s anti-corruption investigations, and Putin’s and the Russian state’s increasing lies and propaganda to smash Navalny’s gaining popularity.

Events move to the point where Dozhd itself becomes the daily news as they broadcast being evicted and shut down. Their lives are in jeopardy, their financial ruin eminent, all in front of a watching public. Natasha, her staff and the station are evicted and move from place to place trying to find somewhere to broadcast from. This happens a number of times. They flee with their equipment. At one point they continue streaming the news from Sasha’s apartment. Then finally, when all else fails and they have no place to physically call Dozhd home, they take the videos of their live feeds and put them on YouTube. By this point in time, Natasha who was wealthy has lost much of everything and Sasha is moving for a divorce.

Vera Krichevskaya’s video clips of what happens during the frenetic times of wheel and woe, evictions, financial losses, being taken off the air, are intercut with Putin’s proclamations that he is censoring no one and is not jeopardizing Dozhd TV. The director’s editing and footage are superb, as is her paralleling the life of Natasha with Russia throughout the decade. Both the populace and Natasha have had their eyes opened and one encourages the other. If not for the Russian people’s need for the truth, there would be no Dozhd TV. Also, the US and EU nations would not know what is happening inside Russia.

Significantly, the director reveals how Natasha evolves as a human being to understand what is important, what is heroic and what is vital. Fighting on the frontlines of the war between Global Truth and Russia’s Repressive Propaganda and malign influence, Natasha and her team put journalists who would be lazy, cowed, narcissistic and selfish to shame. Dozhd’s team risked their lives, lost money and love relationships in pursuing a greater purpose, resistance to Putin’s lies and propaganda. Would all journalists do the same and not be hacks for their editors.

When nothing is left, one knows the value of what is priceless, something which totalitarian governments and their leaders greatly fear and will kill to prevent its coming to the light. The documented truth. Getting the truth out is paramount in a culture where the state media produces only lies to fuel the wealth and power of the totalitarian, autocratic Russian regime under Putin. The same goes for other such regimes around the world. Krichevskaya’s film sounds the alarm loudly and clearly. For the press to be vital, it must be willing to put itself in jeopardy to get to the truth. If the media only exists for itself, it is useless, especially to a citizenry that intends to remain free.

VIMEO LINK: https://vimeo.com/590692770

The award winning F@ck This Job is a must-see film. For tickets and times go to the DOCNYC website. https://www.docnyc.net/program/?alpha=abc The Q and A with producers, director and subjects will be this Friday, November 12 at 7:15 pm Cinépolis Chelsea in NYC.

‘The French Dispatch’ a 59th New York Film Festival Review

Fans of the inimitable Wes Anderson’s droll wit and pixie capriciousness will enjoy The French Dispatch, though it diverges from his other films. Truly, this amazing work spins off Craven’s usual stylistic nuances into the realm of the cinematic magazine. Anderson directed and wrote the screenplay with story help from Jason Schwartzman and Roman Coppola.

Importantly, The French Dispatch pays homage to the magazine he riffs, The New Yorker and the renowned writers from the past (James Baldwin) receive more than a nod. Chock full of references, Craven employs his choice mediums (animated car chase, cartoons, cut out color sets, dead on camera framing) and adds the magazine format. This extraordinary film which engrosses, ridicules, satirizes, mourns, praises, and twits writers past and present screens at the 2021 NYFF until 10 October.

Wryly narrated by Anjelica Huston, the film opens by defining “The French Dispatch” as an eponymous expatriate journal published on behalf of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun. Ironically, Anderson has named the journal’s place of publication as the fictional 20th century French city, Ennui-sur-Blasé. (Ennui=the city, Blasé=the river) Roughly, Ennui-sur-Blasé translates as boredom of the worldly-wise apathetic, a superb irony.

Thus, “The French Dispatch” attempts to make middle-America’s readers acculturated cosmopolitans. By way of explaining the periodical’s cleverness, Anderson’s film brings to life a collection of stories from the final print issue. Indeed, this lively anthology serves as an encomium to the death of its editor-in-chief, the big “gun” Arthur Howitzer, Jr (Bill Murray). Thematically, while highlighting the time in France (1950s-1970s) Craven weaves dark ironies that reference the current times.

Using waggish and epigrammatic descriptions, the narrator presents the quirky, peculiar press corps, writers of the wildly over the top stories activated by Anderson. After the director introduces us to the meticulous Howitzer Jr. and others (look for the writer diagramming sentences on a blackboard) we meet cyclist Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson). Craven uses opportunities for humor through double entendre, with names that have nuanced meanings. For example, “Sazerac” is a beloved bourbon or rye cocktail of New Orleanians.

As Sazerac cycles us via a travelogue through Ennui-sur-Blasé, with shots from the past (black and white) and future (color) we note its dinginess (terraced rat dwellings) poverty, underworld pimps and prostitutes and other charms. In other words, the city reeks of humanity which remains forever unchanging. Of course, “The French Dispatch” reports on stories that identify the weirdest and most comically contradictory of the denizens of humanity.

First, Huston introduces a story, assisted with a lecture at a symposium given by J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) cultural reporter of the “The French Dispatch” arts section. Berensen relates an amazing tale. One of the foremost contributors to modern art remains hitherto for unknown: psychotic criminal artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro). On the brink of suicide, Moses finds his answer to life and love via his sadistic prison guard lover Léa Seydoux

With the unpredictable guard as his muse, Moses immortalizes her in abstracts he paints on the concrete walls of the prison. Like Banksy, Moses prevents his greedy, exploitive art dealer (Adrien Brody) from easily trafficking his art by painting his frescoes on a building making them unremovable. During an investors’ showing in the prison, the prisoners riot to muscle in on Moses’ elite visitors and hold them hostage. Moses’s violent nature, which put him in prison serves him well. With brute force Moses destroys the rioters stopping their attack of the dealer and wealthy purchaser Upshur Clampette (Lois Smith). With his investors saved, Moses receives parole. He has provided his unique contribution to the Clampette Museum, representing abstract fine art at its incredibly ironic, violent best.

Next in the collection, the story of student revolutionaries of 1968 compels its reporter Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) to have an “objective” affair with star revolutionary Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet). Helping to straighten out his befuddled theories and justifications to revise his “manifesto,” Krementz as the “older woman,” influences Zeffrielli. Eventually, he succumbs to his nemesis, the beautiful counterrevolutionary Juliette (Lyna Khoudri) and they stay together until tragedy strikes. Nevertheless, the created manifesto lives on as does Krementz’ reportage, though the revolution, the revolutionaries and their Utopian ideals fade from memory into a fever dream of unreality.

Finally, Huston sets up the story of the dinner with a police commissioner (Mathieu Amalric) and his personal chef Lieutenant Nescafier (Steven Park). Gourmand writer Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) intends to report on the delectable cuisine of the famous Nescafier. However, complications arise when the commissioner, a veritable Jacques Clouseau, has the tables turned on him and criminals kidnap his son. Finally, locating the son, Chef Nescafier prepares a snack which poisons all but the son, the chef and the chauffeur (Ed Norton). The ensuing car chase (a humorous Craven animation) ends with a crash and the son rejoins his father.

At this juncture Howitzer Jr. chides Wright for not describing Nescafier’s cuisine. Wright avers. And thus occurs an incredible moment that alludes to the writing of James Baldwin. Succinctly, Wright describes that he cut out the chef’s words because as an expatriate, the chef, another expatriate made him sad. When Wright repeats Nescafier’s words that he cut, Howitzer Jr. notes with passion that the comment must not be excluded. He insists the Chef’s extraordinary, philosophical observation about the poison in the dish is the only valuable part of the Wright’s work.

Profoundly, in the flash of a moment, we understand why Howitzer Jr. left for this strange outpost in Ennui-sur-Blasé. Fulfilling his goals, he configured a magazine with a global readership that published the profound, the unique, the revelatory. And it included those bits and pieces of life whose revelations edified and informed with a keen, accurate eye. Amazingly, in a brief span of a few moments, Anderson says it all about writing, writers and their editors, finding the elusive and bringing it to our consciousness. Of course, this question Anderson asks silently with The French Dispatch. What happens when censorship, and an absence of prescience, wisdom and freedom runs the presses, as they do currently in the U.S.?

The French Dispatch bears seeing a few times to catch its luxuriant richness. Not only does Anderson employ fanciful images in contradictions journalistically, the resonance of language and word choice is satiric, sardonic and powerful. So is the mosh of well-thought out cinematography and scenic design. For tickets and times at the 2021 New York Film Festival website. https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff2021/films/the-french-dispatch/

‘The Body Fights Back,’ Documentary Review

How do you feel about your physical body? Are you slim, gorgeous, buff, married to a hot man or woman? Or do you fear getting on the scale or if you’re a guy, looking in the mirror because you haven’t been able to work out for two weeks and you know that the flab is growing in leaps and bounds around your middle? Do you have an inner voice that screams don’t eat another piece of pizza or have that cronut? Or do you annihilate that voice and go unconscious eating everything in the fridge after being “careful” and eating only salad and a small piece of fish for your entire food calories daily for one week, though you go to bed hungry?

The Body Fights Back written and directed by Marian Vosumets shadows five individuals from diverse backgrounds that represent all of us at one point or another in our lives as we confront issues of weight, appearance guilt, body shaming, appearance perfection and the subterranean condemnation that the media lays on men and women through the marketing industry, the fashion industry and most predominately the weight loss industry. And this includes you, too, icon of “superior weight loss,” Weight Watchers.

If that is a mouthful about what Vosumets tackles in her documentary, it is because she highlights all of the problems the culture presents for everyone as they attempt to find happiness in getting to the next day. Meanwhile, they must navigate through the dangerous rocks, the images of perfection that are everywhere and that brainwash and bamboozle everyone to internalize self-condemnation because their appearance just “doesn’t have what it takes to get anywhere.”

Vosumets interviews Mojo, a feisty, adorable, overweight black woman, Rory Brown a buff-looking white male, Hannah Webb, a thin, quiet-speaking, young white woman, Imogen Fox, a thin, out-spoken, confident gay white woman, Tenisha Pascal, a confident, bubbly overweight black woman and Michaela Gingel an outgoing, overweight white woman. Each of these individuals is a courageous star who has confronted and battled body shaming, self-ridicule and unhappiness with their appearance identify which was beaten into them by the diet industry and culture at large. Mind you, diets don’t work. Indeed, as one researcher in the film points out, 85% of the individuals who diet again and again go back to their former weight and many gain even more weight. Of course, the diet culture keeps that statistic under wraps.

Recording her subjects’ prescient and brilliantly honest presence and commentary, the documentarian gets at what the diet culture and all of its octopus tentacles (the fashion industry, marketing industry, media in all its forms, health industry) do to destroy the souls of millions of individuals, predominately in the U.K., U.S. and Australia by making them feel inferior and deserving of condemnation, unless they look perfect. Appearance is everything to the diet culture octopus. Unless one fits the image in the billboards, magazines, media, people are the equivalent of worms to be outcast from community and companionship. Importantly, they are not deserving of love, most importantly self-love. Thus, they HAVE to go on a diet to look better. Their lives, which are boiled down to appearance only, and never includes their treasured souls, depend on dieting to look good. If they don’t diet, they face the outer darkness.

If this sounds like hyperbole, it is. Diet culture and all of its psychotic means to make billions of dollars a year exploiting fear of fat, will stop at nothing to twist the minds and hearts of everyone. Let’s face it, women, if you’re not a BMI 18-20, you’re a pig. The sacrosanct thin people who fit this weight category are most probably in some form of eating disorder or addicted to pills, cocaine, smoking, crack, heroin, etc. Celebrities have revealed their disorders and addictions to stay thin: anorexia, bulimia, binging and purging, cocaine addiction, speed addiction, crack, heroin and more.

Hannah Webb truthfully discusses how doctors missed her eating disorder because they, too, had fallen for the lie that healthy people are always thin people. She weighed within a normal range of BMI, which is not an accurate indicator of health; other factors must be taken into consideration. Thus, Hannah lived a lie which made her miserable until she confronted it. In poignant discussions with her mother captured by Vosumets, she discusses battling her issues with eating, for example, a croissant and constant fears of gaining weight. With her disorder she was on the verge of life and death. Yet, she was able to come out of it with the help of her family and therapy.

Hannah is the opposite side of the same coin as Mojo, Michaela, Tenisha and Imogen, all of whom had or have issues about weight. Imogen also battled a disability and discusses that when she was heavier, the hospital staff were very insulting and annihilating about getting her a gown to fit (get her a man’s gown which is bigger) and other obnoxious calumny in front of her face, almost as if they enjoyed and felt sanctified in their sadism.

But this is par for the course. Overweight in the culture is anathema and grounds for banishment from normal society. It deserves vilification, ridicule, jokes and shaming. How unhealthy these fatties are!!! Of course, this emerges from colonialism, white male paternalism (women must be quiet, thin, beautiful and sexually available 24/7 and perfect until they can be thrown away for another model) and capitalism-make that money even if you have to step over the bodies of those you kill in the process.

TRAILER The Body Fights Back OUT July 13 from The Body Fights Back on Vimeo.

The diet culture, thus, reinforces the most nihilistic of values at the expense of truth and health. Vosumets has researchers and scientists comment that one could be thin and on the verge of death; overweight is not correlated to healthiness. Indeed, based upon appearance, Hannah and Imogen who are at the epitome of thin (according to the diet culture and Octopus standards) are perfect and sanctified. Ironically, they are not; one battled for her life just to eat certain foods without fear and the other is disabled. Thus, the diet culture lies. It is its own profitable myth. (diets don’t work) And this is one of the key points in Vosumets’ wonderful documentary. What is healthy should include physical, mental, emotional, psychic well being. We are, after all, not only a body; we have a soul and spirit. And indeed, the body disintegrates. However, what are we doing about the interior of our lives? No wonder with eating obsessions individuals are miserable, regardless of how thin and buff they appear.