Category Archives: Lincoln Center Film

‘Anemone’ @NYFF Brings Daniel Day-Lewis’ Sensational Return

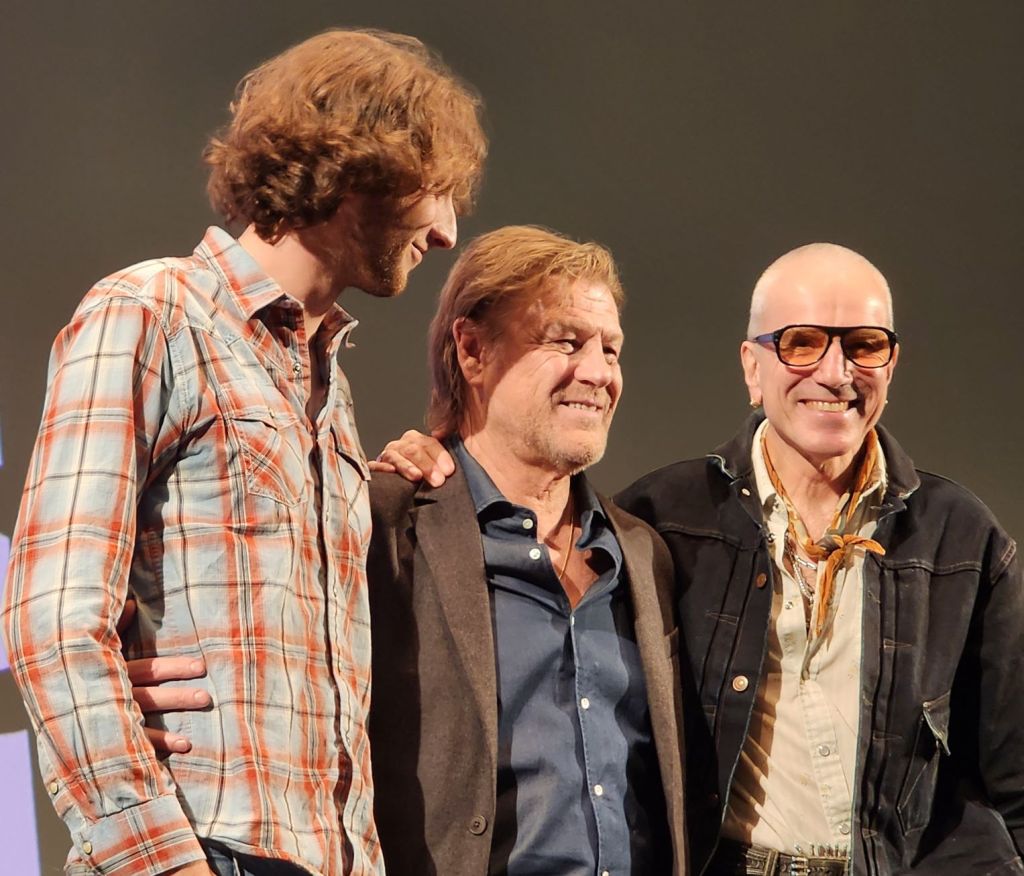

Supporting his son Ronan Day-Lewis’ direction in a collaborative writing effort, Daniel Day-Lewis comes out of his 8-year retirement to present a bravura performance in Anemone. The film, his son’s directing debut, screened as a World Premier in the Spotlight section of the 63rd NYFF.

Ronan Day-Lewis’ feature resonates with power. First, the eye-popping natural landscapes captured by Ben Fordesman’s cinematography stun with their heightened visual imagery. Secondly, the striking, archetypal symbols illuminate redemptive themes. Day-Lewis uses them to suggest sacrifice, faith and love conquer the nihilistic evils visited upon Ray (Daniel Day-Lewis) and ultimately his entire family.

Finally, the emotionally powerful, acute performances, especially by Daniel Day-Lewis’ Ray and Sean Bean’s Jem, help to create riveting and memorable cinema.

The title of the film derives from the anemone flower’s symbolic, varied meanings. For example, one iteration relates to Greek mythology in the story of Aphrodite, whose mourning tears, shed after her lover Adonis’ death and loss, fell on the ground and blossomed into anemones. Also referenced as “windflowers,” anemone petals open in spring and are scattered on the wind. Possibly representing purity, innocence, honesty and new beginnings, the film’s white anemones grow abundantly in the woodland setting where reclusive Ray makes his home in a Northern England forest.

In a rustic, simplistic hermit-like retreat Ray lives in self-isolation, alienated from his family. Then one day, his brother Jem, prompted by his wife Nessa (Samantha Morton), mysteriously arrives. The director focuses on the action of his arrival withholding identities. Gradually through the dialogue and the rough interactions, heavy with paced, long silences, we discover answers to the mysteries of the estranged family. Furthermore, we learn the characters’ tragic underpinnings caused by searing events from the past. Finally we understand their motivations and close bonds despite the estrangement. By the conclusion family restoration and reconciliation begins.

Unspooling the backstory slowly, the director requires the audience’s patience. Selectively, he releases Ray’s emotional outbursts. These reveal his decades long internal conflict with himself, for not standing up to the perpetrators of his victimization. Neither Jem nor Nessa (Samantha Morton), Ray’s former girlfriend who Jem married after Ray abandoned her and their son, know his secrets. However, the slow revelations of abuse spill out of Ray, as Jem lives with him and endures his ill treatment and rage.

Each brief teasing out of pain-laced information that Jay spews impacts Jem. Because Jem receives strength and understanding from his faith, he puts up with Ray. Indeed, the various segments of Jay’s story seem structured as turning points. Each moves us deeper into Jay’s soul and Jem’s acceptance. Cleverly, by listening to his brother and encouraging him to speak, Jem breaks down Ray’s resistance.

Ray and Jem’s emotional releases trigger and manipulate each other. Once set off, the revelations full of anguish and subtext fall in slow motion like dominoes. Then, climactic sequences augment to an explosive series of events. One, a treacherous wind and hail storm, represents the subterranean rage and turmoil which all of the characters must expurgate before they can heal and come together.

Jay particularly suffered and needs healing. Throughout his life the patriarchal institutions he trusted betrayed and abused him. From his home life (his father), to the church (a cleric), and the military (his immediate superiors), emotional blows attack his soul and psyche. Also, the military makes an example of him. Not only was the abuse unjustified and misunderstood, the perpetrators covered it up and forced his silence. The cruel, forced complicity makes his life a misery in a perpetuating cycle of guilt and shame.

As a result, because Jay’s self-loathing pushes him deeper within his pain, he can’t discuss what happened with his family or anyone else. Of course, he refuses to get help in therapy. Instead, he escapes into nature for solace and peace. The society’s corruptions and his family’s still embracing the institutions that abused him stoke his anger and enmity.

Neglecting his brother Jem, Nessa and his son Brian, who is grown and needs him, Jay perpetrates a psychological violence on them. None of them understand Jay’s abandonment. Sadly, Ray’s absence and rejection shape Brian’s life. Embittered and violent, he endangers himself and others.

How Day-Lewis achieves Ray’s epiphany through Jem’s love occurs in an indirect line of storytelling, through Ray’s monologues and the edgy dialogue between Jem and Ray. By alternating scenes of Nessa and Brian in the city with the brothers in the forest, we realize that time is of the essence. Jem must convince Ray to return to their home to make amends with his son Brian as soon as possible because of a looming threat.

Ultimately, the slow movement in the beginning dialogue could have been speeded up with a trimming of the silences. However, Day-Lewis purposes the quiet between the brothers for a reason whether critics or audience members “get it” or not. The silences reveal an other-worldly, telepathic bond between the brothers. Likewise, on another level Ray’s son Brian connects with his father spiritually, though they are miles away. The director underscores this through Nessa who understands both father and son need each other. Nessa encourages Jem to bring Ray home to Brian. Day-Lewis also uses symbolic visual imagery to suggest the spiritual bond between father and son.

In Anemone, the themes run deep, as the filmmakers explore how love covers a multitude of hurts and wrongdoings. Anemone releases in wider expansion on October 10th in select theaters. For its 63rd New York Film Festival announcement go to https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff/films/anemone/

‘The Tale of King Crab’ (De Granchio) is Superb Cinema and a Parable for Today

The Tale of King Crab (De Granchio) is a cinematically rich and gorgeously landscaped parable of forbidden love, identity, classism, soul freedom, and the power of storytelling to communicate wisdom and human fealty that rhetoric cannot. Written and directed by Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis, De Granchio made its World Premiere at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival-Directors’ Fortnight and was an official selection at the 2021 New York Film Festival. The film went on to win 7 awards out of its thirteen nominations. Stunning and memorable for Simone D’Arcangelo’s cinematography and Vittorio Giampietro’s haunting, striking music, the layered story by de Righi, Zoppis, Tomasso Bertani and Carlo Lavagna moves through conflict and reprisal to suspenseful, eerie adventure before it settles on its mystical takeaway.

The film begins with the image of a bearded man who appears backlit in the shallow edge of a lake, picking up a thin golden hued ornament lying underwater on pebbles. From the shimmering lake image filmmakers transfer to the present evening where Bruno awaits his paesani who are elderly hunters in modern day Tusci, Italy. The established community of friends gather to eat pasta, sing, drink wine and reflect upon generational stories some have heard and others have not, as they enjoy each other’s company and fill in gaps of information for elucidation and edification.

The storytelling and communal singing is a throwback to ancient times when hunter-gathers and indigenous people sat around the campfire and shared lessons which entertained, yet brought a chill of recognition that would heal and uplift in cathartic moments of revelation. Likewise, in their film the directors pay homage to the process of storytelling with their extraordinary images and beautiful shot compositions. The arc of development is surprising because their spare evocative minimalism keeps the viewer enthralled, worried and engaged.

As the filmmakers flit from present to past, they unravel the legend merging the generational aspect of the tale as the elders in the present portray characters from over a hundred years ago. For example Bruno, who is the chief story-teller, singer (Tosca) and local Inn Keeper of Luciano’s village transposes from the present to the past and back to the present when the story takes an incredible voyage to a strange land of monstrous beauty.

As all great stories combine the fascination of the listeners as they build on the fascination of listeners past, the listeners intrude in the beauty of this legend of Luciano (Gabriele Silli) whose name in Spanish, Italian and Portuguese means light. Indeed, this Luciano is a bearer of light. He manifests this treasure because he has experienced great pain. As we watch his journey from weal to woe, we note his perception and growth as a man who has gained the wisdom to receive the timelessness of spiritual love.

The film progresses after the hunters eat. Bruno sings a refrain of the legend of Luciano, a doctor’s son in the town of Vejano, Italy around the turn of the century, near the place where they now hunt. Bruno sings the second refrain which in two lines summarizes the first chapter of events. Filmmakers use the haunting melody of Bruno’s song carried by a lone flute transporting us into the flashback of the past in the remote town in Tuscany, where the tall, massively dark bearded Luciano drinks from a bottle and meanders along the road, whistling the same melody that Bruno sang, as we seamlessly move from present to past. In Bruno’s voice over we note that the townsfolk have labeled Luciano many things, crazy, a drunk, a saint, an aristocrat, and as the film progresses, he is the full measure of all these characteristics and more.

Luciano lives a life of leisure it would seem, as a doctor’s son with possibly aristocratic patronage in a town of the very poor and a prince who lives in a castle. The “prince” is a vestige of feudal times which have just ended with Italy’s unification twenty years before. Immediately, the story moves to Luciano’s classist conflict with the prince who has blockaded a shortcut path through his property to the other side of the village. It is a path which has been accessible for generations. Seeing the gate has been locked and one of the shepherds has been inconvenienced, Luciano breaks open the gate and the shepherd takes his sheep through, even though he warns Luciano the prince will press charges for the damage.

We understand why Luciano accompanies the shepherd. He has a daughter Emma (Maria Alexandra Lungu) that Luciano has known for years and with whom he has formed a love attachment. They meet and talk to each other and Luciano gives her the thin ornament he retrieved from the lake that he tells Emma is Etruscan gold that has great significance. It is then she tells him of a dream she had about him and a desire for her destiny. How her dream comes true by the conclusion of the film is rapturous, if you understand the profound significance.

During the course of the next scenes, we learn that the prince has strengthened the locked gate and has hired two uneducated, crass thugs to confront Luciano in the Inn where he goes to drink, though his father warned him not to. When they tell him not to break the gate again, Luciano’s toast reveals his character and the nature of the town’s burden of class inequity between rich and poor. Luciano drinks to the prince, to their rights and to the Republic. When one of the thugs asks what he means, Luciano says, “Who do you think you are? You’re just pawns!” When the brute goes to respond with a smack, Luciano shows no fear and dares him, receiving a blow which knocks him out.

It is clear Luciano is ahead of his time and could be a leader against the prince’s oppressive, arrogant attempts to hold on to power signified by the ungracious act of locking a right of way his family allowed for generations. However, Luciano’s alcoholism provokes others and causes trouble for his father who takes him home, chides him then comforts him. Luciano humbly apologizes, tells his father he loves him and demeans the greatness of his character by claiming he’s just a “drunk.”

During their talk Luciano reveals he’s in love with Emma. His father gives him a piece of advice, that Severino, despite Luciano’s heritage, will not allow him to marry her. He doesn’t approve of Luciano. Knowing his daughter is fond of Luciano, Severino provokes Luciano with the thought that the Prince is interested in her when she goes to the Prince’s castle to prepare for the procession.

Indeed, Severino has given permission for his daughter to be dressed in feudal clothing as La Donna in the Saint Orsio procession. When Luciano confidently confronts her in the presence of the wealthy at the castle while they decide what she should wear, she admits she doesn’t fit in. One of the prince’s friends arrogantly states that Luciano is “a ghost,” as he speaks to Emma. This nobleman refuses to acknowledge that Luciano takes a rebellious stand in attempting to prove that the prince and the wealthy caste are like everyone else in Italy, even if they have money, since it has become a Republic.

Meanwhile, Severino elicits the help of the thugs to go after Luciano who is now the enemy of Severino and the Prince. Luciano, fueled by the wine from the communion table (symbolic), shows he will not be ruled by the prince in a symbolic act which ends in a catastrophe and horrific incident. Ambiguously, the filmmakers infer that Emma may or may not have been attacked and raped as the thugs take her to the prince, a situation that is unbeknownst to Luciano.

Filmmakers switch to the present and the hunters discuss that the catastrophe forces Luciano to flee the town and go to Argentina where he lives in exile. And they warn that from that point on, the story becomes unreliable. Filmmakers take us from the comfort of the apparently truthful paesano in Italy and launch out across the ocean where the story transports us into the realms of the mythic.

The next time we see Luciano and hear him in a voice over, he is wearing the cassock of a Salesian priest and on a treasure hunting adventure in “The Asshole of the Earth,” an island in the remote and visually fearsome and beautifully barren Tierra del Fuego. Here the music and cinematography meld in a pageantry of images, sounds and silences that create suspense and drama. Luciano must protect himself from vicious pirates who have nothing to lose in their search for gold as they accompany him in the hunt.

Luciano is the map to the gold with the help of a creature who is the most unlikely traveler up mountains and through rocky terrain, spongy tundra and wind-blasted trees. Together, the men look for the lost gold of the shipwrecked Jacinta owned by the Spanish monarchy. The Jacinta’s captain and crew died because they underestimated that death lurked everywhere on the island where they landed.

As the legend creates a life of its own, the hunters in the present fade away. Luciano becomes the hero living his legend before us. Resilient, experienced in fighting off those out to destroy him, Luciano proves to be far from the ghostly figure the arrogant lord described him to be years before. He has matured and stopped drinking. Valiant and on a mission to return home with gold, he delivers the drama, excitement and amazing revelation in this final chapter of his story. And as a legendary hero, he himself learns the significance of the gold ornament that he picked up in the lake in Tusci where we glimpsed him in the first image of the film.

This setting in the second segment of the film, like the tone and mood is stark, desolate and hardscrabble, as the first chapter is romantic, luscious and tragic. Filmmakers add even greater depth to the characterization of Luciano showing he has become more poetic, insightful and ironic in his search for the gold which becomes synonymous with home. Also, the filmmakers continue paying homage to the process of storytelling to uplift and educate in this segment as well. It is through the indigenous peoples’ stories someone wrote down that Luciano learns of the golden treasure on the island and how to find it.

In learning about the gold, Luciano, humorously states words to the effect, “I saw an opportunity. After all, this is America.” We are reminded of the stories that brought the explorers to the new world, and the emigrants who are brought to the Americas because of the streets metaphorically are paved with gold. However, for Luciano, the gold signifies something intangible. Interestingly, the symbolism and multiple meanings of this are revealed at the film’s conclusion. Most importantly, as a result of Luciano’s incredible journey to the other side of the world, he is brought to the greatest depths of his own spiritual growth and golden nature. Of course his greatness was within him all along, he just had to realize it.

The film is just dynamite in its multi-dimensional themes, (one of which is immigrants forever wish to return to home), homage to storytellers who keep legends alive, cinematic beauty, superb music, sound design, pacing and all of what I’ve mentioned above. Filmmakers were anointed ushering in the fabulous inwardly deep performance by Gabriele Silli whose piercing blue eyes seem to have traveled to deeper realms than we can ever understand. As his accompaniment the sweetness and peasant nobility of Maria Alexandra Lungu is graceful and worthy of the object of his forever love.

This is one to see. It opens in New York City on April 15 at Film at Lincoln Center. For tickets and times go to their calendar. https://www.filmlinc.org/calendar/ In Los Angeles The Tale of King Crab opens April 29th.

If you are in NYC why not get a membership to Film at Lincoln Center. With it you’ll be able to get a heads up on some of the finest films in the world as well as Academy Award Winners often predicted at the New York Film Festival.

Lincoln Center Film, Joachim Trier: ‘The Oslo Trilogy’

Norwegian Film Director Joachim Trier is being celebrated at Lincoln Center Film for his most recent film, The Worst Person in the World, which screened at the NYFF 2021. This is the third film in his collection, The Oslo Trilogy, which includes Reprise (2006) and Oslo, August 31st (2011) all of which feature the superb Anders Danielsen Lie who interestingly is a practicing physician and an actor. The Trilogy screenings on select dates will be followed by Q and As by Joachim Trier, Anders Danielsen Lie, and Renate Reinsve (The Worst Person in the World) and Joachim Trier and Anders Danielsen Lie for Reprise and Oslo August 31st. Click for tickets here. https://www.filmlinc.org/daily/the-oslo-trilogy-with-joachim-trier-and-renate-reinsve-in-person-begins-jan-28/

The title of the collection of films centers around the city where Joachim Trier was born and grew up. The setting of each of the films reflects upon sections of Oslo, Norway that Trier revisits and encapsulates while he integrates his various story arcs in each film, whose themes interlock and concern ambition, dreams, identity, loss, satisfaction memory, isolation.

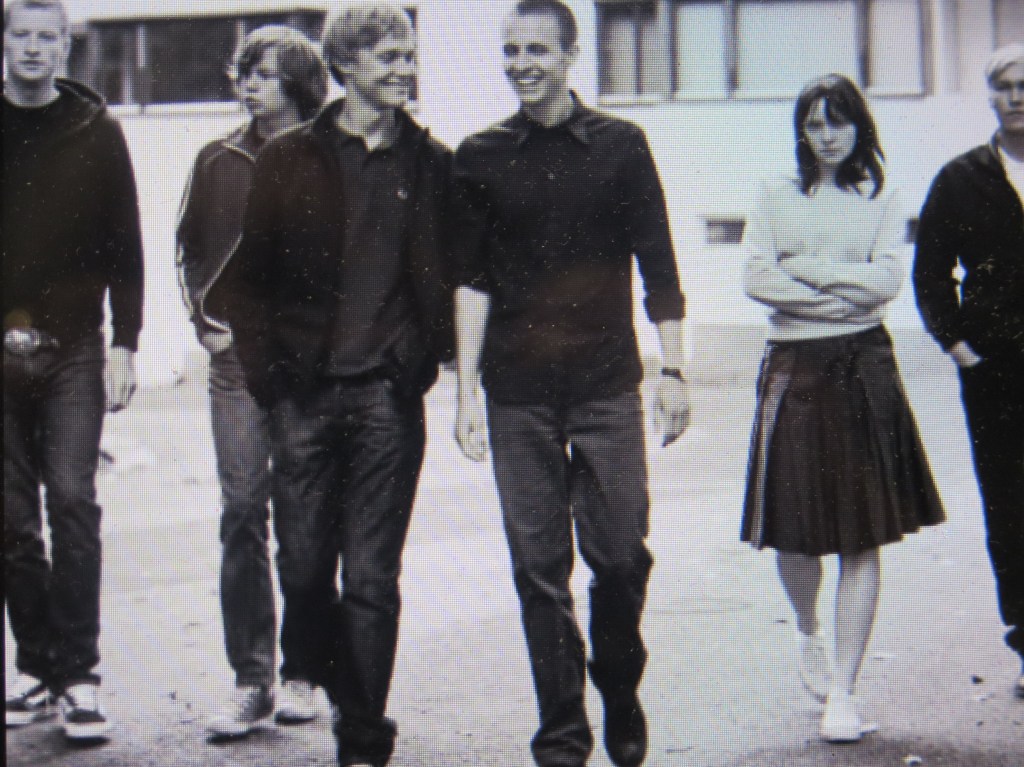

Reprise captures the society of twenty-something friends from Oslo as they plan their lives and attempt to actualize their dreams. Trier separates out two budding writers, Erik (Espen Klouman Høiner) and Phillip (Anders Danielsen Lie) and places them under a microscope, allowing them partial successes, and ups and downs as they move along divergent paths with one ending up nearly taking is life, though his novel has achieved a modicum of success. As Erik attempts to help Phillip get back on his feet and regain a love relationship which was broken off, he confronts his doubts about his writing attempts. We watch the unfolding of their uncertainties, depressions and the excitement and hope of a satisfying writing career.

In Reprise, memory and fantasy merge in the comedy-drama that is playful and whimsically hopeful. As the writer’s imagination takes over Erik, we understand that he may achieve a possibility of success. Of course, the irony is that Phillip has achieved writing success, but it isn’t enough for him; returning to a former love is what matters. Thus, achieving their out-of-reach dreams remains different for both friends. And it is only through Erik’s imagination that they manifest the goals that make them happy.

The tone of Reprise turns darker and the comedy becomes muted in the award winning Oslo, August 31st which is loosely based on Pierre Eugène Drieu La Rochelle’s novel Will O’ the Wisp. This second film of the Oslo Trilogy is also written by Eskil Vogt and Joachim Trier and examines the interior soul psychology of the life of a recovering drug addict. When the film opens, Trier cleverly introduces us to Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie) without a hint of his enslavement to his former addiction when he walks to a river and attempts suicide unsuccessfully. From then on we understand the stakes and question how and why he has arrived on the brink of death only to eschew it. Trier keeps us in a state of tension as to whether Anders has given up or plans to try again.

From this initial uncertainty of details about where he has come from (the woman he slept with) and how he arrives at the beautiful house where they seem to know him when he walks in the door, we learn that Anders is in a rehab center. During his group therapy session, we learn he had a severe drug addiction and emotionally, he tells the group that he has been stable. This information collides with the previous scene; it is obvious he is lying and in group therapy, he has not dealt with the interior pain of his emotions or psyche.

Nevertheless, on August 30 Anders is journeying on a new road in his life as the therapist discusses the job interview which has been set up for him, though he is not enthusiastic about it. Then, as he takes off for the interview he makes a number of stops along the way, during which time he will see his sister and visit his home which his parents are selling to pay for his rehab.

It is on this journey, we discover he is in touch with his inner self. The darkness within is confirmed when he visits and confesses to close friend Thomas (Hans Olav Brenner) that he finds little purpose to his life and that he doesn’t think he ever loved his former girlfriend Malin, whose bed he leaves then tries to kill himself. In his discussion with Thomas, he even confesses that he doubts his love of Iselin with whom he had a long relationship and a rocky breaking off. The irony is that he is clean. The rehabilitation worked to settle him away from addiction, but it didn’t help him fill the cavernous soul abyss which overwhelms him in the thought that he has no reason to live. It becomes obvious that he used drugs to deaden the pain and ferry him away to a land of oblivion.

Ironically, when he confides to Thomas that he is suicidal, Thomas confesses that he is not happy in his life; that he has stopped finding passion with his wife and that he is going through the motions of living and raising kids. As they confess their trials to each other, they achieve a greater closeness, but that doesn’t assure Thomas that Anders won’t take his life. Thomas makes Anders promise he won’t commit suicide, and Anders obliges his friend. Nevertheless, because we have seen Anders’ suicide attempt at the top of the film, we are not convinced that he won’t try to end the meaninglessness of his life and pain of living.

Trier presents Anders’ soul/psyche condition in a series of worsening failures, spiraling him and us further into the black hole toward death. The journey on his leave from rehab takes him to his unsuccessful job interview, his failed meeting with his sister Nina, a party where he waits for Thomas who doesn’t show, to a drink after months of no alcohol, to a bar with old friends and more drinks, to a return to his old haunt at his dealer where he scores a large batch of drugs. On August 31st, when he reaches his parents’ home that is in disarray for Anders’ sake, being packed up for sale to save Anders’ life, the inevitable occurs.

Trier’s cinematography won a well-deserved award and the acting by Anders Danielsen Lie is heartfelt, profound and emotionally driven with a low key beauty and sensitivity, beautifully shepherded by Trier’s direction which is wonderful as is the editing. There is just enough cinematic silence and imagery to draw us in and keep us engaged with Anders’ journey, as we are being led emotionally, invested in Anders’ survival. This is one to see and is the explanation of another reflection of Oslo, Norway at a time when Oxycotin and heroin had been ravaging global culture.

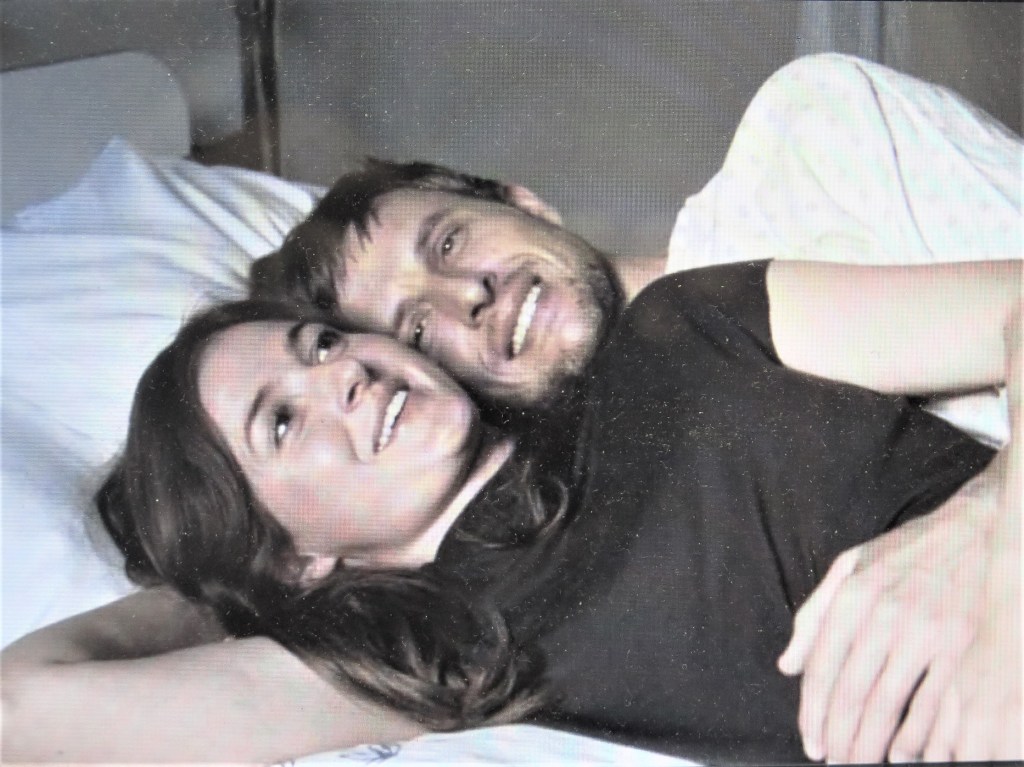

The Worst Person in the World is a dark romantic comedy-drama that chronicles four years in the life of Julie (Renate Reinsve). Like with Trier’s other two films, the protagonist is a young, in this focus, a woman looking for her own autonomy and identity as she negotiates the deep and roiling subterranean channels of her love life. Facing uncertainty with her career path and struggling to gain stability and balance, she eventually attempts to view herself realistically and authentically, despite her desire to avoid looking in the mirror.

Once again Joachim Trier hits is out of the park and like in Oslo, August 31st, The Worst Person in the World is a multi-award winner. Renate Reinsve is devastatingly brilliant and translates an authentic performance into a beloved, flawed human and believable woman.

Don’t miss this marvelous triumvirate of great films by Joachim Trier and the Q and As with the director and lead actors by first reserving seats and purchasing tickets at https://www.filmlinc.org/press/flc-announces-joachim-trier-the-oslo-trilogy-january-28-february-3/

Press Release for Film at Lincoln Center: ‘Camera Man: Dana Stevens on Buster Keaton’

“Steamboat Bill, Jr. may be Keaton’s most mature film, a fitting if too-early farewell to his period of peak creative independence … its relationship to the rest of its creator’s work has been compared to that of Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest.”

– Dana Stevens on Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Camera Man: Dana Stevens on Buster Keaton, screening on January 27 at 7:00pm at the Francesca Beale Theater in the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center is one you don’t want to miss if you love Buster Keaton and the film Steamboat Bill, Jr.

To mark the upcoming release of her new book Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century, author and Slate film critic Dana Stevens joins Film at Lincoln Center for an extended conversation with writer Imogen Sara Smith. A screening of the 4K restoration of Keaton’s silent comedy masterpiece Steamboat Bill, Jr. follows, preceded by a 2K restoration of the classic two-reeler One Week. Both films are from the Cohen Film Collection and feature 5.1 orchestral scores by composer Carl Davis.

Known as “The Great Stone Face” due to his deadpan facial expressions and mannerisms during the Silent Film era, Buster Keaton left an enduring impression on film history. On Keaton’s breakneck productivity and prolific output of films throughout this period, film critic Roger Ebert said: “from 1920 to 1929, he worked without interruption on a series of films that make him, arguably, the greatest actor-director in the history of the movies.” Keaton’s experience with pratfalls and showmanship from vaudeville performances as a child evolved into his eye-popping, unforgetable achievements in Steamboat Bill, Jr. as well as The Cameraman, The General, and Sherlock Jr., all of which have been selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Dana Stevens is the film critic at Slate magazine and a co-host of the Slate Culture Gabfest podcast. She has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and Bookforum. She lives in New York City with her family. Camera Man is her first book.

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy and In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City. A regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and the Criterion Channel, she has also written for Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Cineaste, Reverse Shot, and many other publications.

Camera Man: Dana Stevens on Buster Keaton is organized by Madeline Whittle.

Tickets, on sale beginning on Friday, December 18 are still on sale. Pricing is $15 (General Public), $12 (Students, Seniors, Persons with Disabilities), and $10 (Members). Save on FLC memberships this month only! Learn more here.

Films and Descriptions

The event will take place at the Francesca Beale Theater (144 W 65th St)

Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Charles Reisner, 1928, USA, 70m

In the 10th and final feature to emerge from Buster Keaton’s independent production unit, the legendary comic master turns in an iconically endearing performance as the eponymous Bill Jr., a college student who returns home to help his scheming riverboat captain father (Ernest Torrence) compete with the far more successful luxury-riverboat owner J.J. King (Tom McGuire)—who also happens to be the father of Bill Jr.’s sweetheart. To make matters worse, a cyclone blows through the area, setting the stage for some of Keaton’s finest stunts on camera and one of the most (deservedly) storied sequences in all of silent cinema, in which a house’s actual two-ton facade falls on the oblivious young man. 4K Restoration by Cohen Media Group in collaboration with the Cineteca Bologna.

Thursday, January 27, 7:00pm (Q&A with author Dana Stevens and writer Imogen Sara Smith)

Preceded by:

One Week

Buster Keaton & Edward F. Cline, 1920, USA, 25m

A man and his new bride set about assembling a home for themselves with a build-your-own-house construction kit, only to encounter unforeseen pitfalls resulting from a disgruntled former lover’s sabotage. 2K Restoration by Cohen Media Group in collaboration with the Cineteca Bologna.

FILM AT LINCOLN CENTER

Film at Lincoln Center is dedicated to supporting the art and elevating the craft of cinema and enriching film culture. For any questions go to: http://www.filmlinc.org