Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

‘Sing Street’ a Stirring Musical Adaptation of the Award-Nominated Titular Film

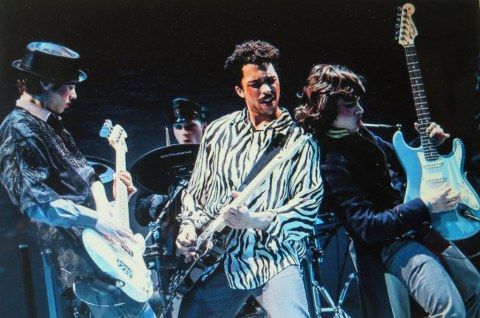

Brenock O’Connor (center) and company, Sing Street, book by Enda Walsh, music & lyrics by Gary Clark & John Carney, based on the film written and directed by John Carney, original story by John Carney & Simon Carmody, choreography by Sonya Tayeh, directed by Rebecca Taichman, NYTW (Matthew Murphy)

It’s 1982 Dublin, Republic of Ireland. The country is in a recession and there is no work anywhere. Those with mobility and ambition leave for London and the United States, while the Conors led by out-of-work architect Dad (Robert is played by Billy Carter) and his family exhaust their savings and downsize their lifestyles. The circumstances create drama for the lives of the struggling family of five in writer/director John Carney’s vibrant if thinly drawn theatrical adaptation of his 2016 film Sing Street, currently enjoying its run at New York Theatre Workshop until 26 January.

Based on Carney’s film, the comedy/musical with dramatic elements is directed by Tony Award winning Rebecca Taichman (Indecent 2017) with book by Enda Walsh, music and lyrics by Gary Clark and John Carney and choreography by Sonya Tayeh. The original story is by John Carney and Simon Carmody.

Sing Street has additional songs (others from the film have been pared), with selections from iconic tunes from New Wave and pop groups including songs by Depeche Mode, Spandau Ballet, Japan and others. And there are original songs, some of them from the movie, co-written by John Carney and Gary Clark (former lead of Scottish band Danny Wilson from the late 1980s).

Enamored by Carney’s film Taichman was inspired to adapt the film for the stage. She pursued the project, meeting Carney in London where additional conversations and meetings resulted in Enda Walsh writing a first draft of a libretto using the score from the film. The project evolved. There were more creative meetings and additional work periods and a refining of book and music with extensive development at New York Theatre Workshop that incorporated movement.

Considering that Carney and Walsh had brought together a theatrical adaptation of Tony Award Winning Once (from Carney’s 2007 film Once), beginning Off Broadway at NYTW (2011), and shifting to Broadway in 2012 (garnering 8 Tonys and other theater awards), the creative team appears golden. Will Sing Street follow the same trajectory as Once to land on Broadway when it is ready? Its incubation at NYTW looks to be moving it in the right direction.

(L to R): Sam Poon, Anthony Genovesi, Jakeim Hart, Gian Perez in Sing Street, book by Enda Walsh, music & lyrics by Gary Clark & John Carney, based on the film written and directed by John Carney, original story by John Carney & Simon Carmody, choreography by Sonya Tayeh, directed by Rebecca Taichman, NYTW (Matthew Murphy)

As in Once, the actors are talented musicians/singers. They play a wide variety of instruments to make up the band that teenage Conor (Brenock O’Connor), seamlessly puts together to impress and lure Raphina (Zara Devlin), who presents herself as a “model.” Impressed, smitten by her look and demeanor, Conor invites her to appear in a music video with his band. Conor’s pitch is a stretch for he has no band and most probably Raphina who has dropped out of school to “become” a model is laying it on “thick” as well. But no matter; the die is cast, and the intrigue is on. Both have made each other the inspirational backboard upon which to encourage and solidify their dreams and hopes.

Since Conor’s family’s fortunes have spiraled downward, he must attend the reasonably tuitioned state-run Christian Brothers school on Synge Street (named after John Millington Synge the poet, playwright, prose writer, political radical and co-founder of the Abbey Theatre). That Conor decides to turn a curse into a blessing by morphing the name of “Synge” to “Sing” as part of the title of his band is his ingenious, if not ironic touch, because the venue where he must attend school is anything but desirable, initially. Nevertheless, as one of the many themes of the production, Conor pushes himself to the top of a coal heap and turns coal into diamonds withstanding the pressure he undergoes in the school and on this street.

The new environs are a far cry from Conor’s Tony elite Jesuit school where he fit in and did well. The headmaster of Christian Brothers, Brother Baxter (Martin Moran) is a martinet who challenges Conor at every turn, even to censuring him for defying the regulation color of his shoes (they must be black). Conor doesn’t have the money for new ones, but if he did, he would most probably spend it on something more uplifting and useful.

Their disagreements and Baxter’s unexplained wrath grow into a peaked conflict which could be deepened beyond Baxter’s one-sided characterization. He is, rather a stereotypical, cleric “bad-guy,” antagonist to Conor’s angelic-faced, innocent whom we root for unquestioningly because he’s heading up a boy-band with grand ambitions. What’s not to love about Conor? What’s not to dislike about Brother Baxter? Complexity is wanted.

Zara Devlin, Brenock O’Connor in Sing Street, book by Enda Walsh, music & lyrics by Gary Clark & John Carney, based on the film written and directed by John Carney, original story by John Carney & Simon Carmody, choreography by Sonya Tayeh, directed by Rebecca Taichman, NYTW (Matthew Murphy

Conor is also at odds with some outliers in the school community who bully him and beat him up, i.e. Barry (Johnny Newcomb), whom we discover to be gay and hiding under machismo thuggishness. Classically, his warped background and lack of self-knowledge or acceptance about who he is provokes his bellicosity. Walsh and Carney reveal his vulnerability in his scenes with Sandra (the superb Anne L. Nathan), rounding out his character and revealing his development.

Interestingly, it is the adversity reflected in the change of schools that forces Conor to rise to the occasion guided by his college-drop-out brother Brendan (the sensational Gus Halper), to establish his band (the most entertaining and delightful part of Act I). In the process of tackling obstacles to bring together clever and talented Eamon (Sam Poon), Kevin (Gian Perez), Larry (Jakeim Hart), Gary (Brendan C. Callahan), and Darren (Max William Bartos), Conor gains confidence and shares his enthusiasm and empowerment with his band members. The feelings are mutual. This bravado helps him in a face-off with Barry and eventually inspires him to stand up to Baxter’s niggling injustices. The climax of their conflict comes in Act II, after Baxter gives Conor and his “Sing Street Band” permission to enter The Inner-City Dublin School Band Contest, then sadistically punishes Conor by retracting his permission. Conor and the Band’s response is joyous.

Underscored throughout is Conor’s growing love relationship with Raphina, despite her threat to be pulled away to London by her boyfriend, and Conor’s deteriorating family situation as his father splits with his mother Penny (Amy Warren). Penny moves out to fulfill an affair with her boss. Conor’s sister Anne (Skyler Volpe), and older brother Brendan, who himself needs a resurrection into a new person since he can’t move himself to leave the house, are Conor’s support group. The scene where the family situation blows up rings with authenticity, and we are happy as is Brendan (Halper’s song at the finale is just terrific), that Conor is able to break away and leave with Raphina, enriched and enlivened by what he has accomplished on Synge Street, with “Sing Street.” Conor truly has reversed his fortunes and spun out a golden path for himself.

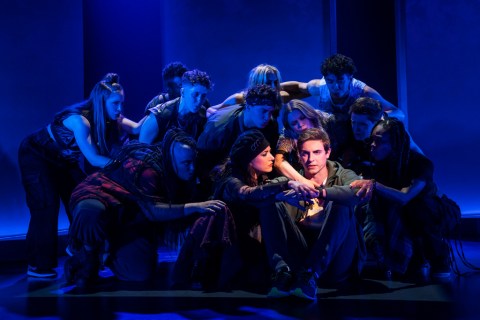

Brenock O’Connor (center right) and company, Sing Street, book by Enda Walsh, music & lyrics by Gary Clark & John Carney, based on the film written and directed by John Carney, original story by John Carney & Simon Carmody, choreography by Sonya Tayeh, directed by Rebecca Taichman, NYTW (Matthew Murphy)

The music and performances are steady, effervescent and fun; it is a joy to be returned to the 1980s era which was nothing short of vibrant. We are in a different environment with a projection of the Irish Sea beckoning in the background, the waters flowing at the conclusion of the production. The band’s movements/song performances are right-on and glorious, and it is a rally to watch O’Connor’s Conor work his magic with confidence spurred on by Halper’s Gus who is gobsmacking in the role as Conor’s caring older brother.

The love relationship that develops between Raphina and Conor is convincing; though indeed we wonder how much of Raphina’s riffs to Conor are a complete front job. What does the future have to offer for a female drop out who comes from a troubled family life? Love from someone as appealing, dynamic and ambitious as Conor is a miraculous gift. She would be a fool to spurn him.

In its verve, positive themes, joyful celebration of 1980s music and triumph over a time of doldrums in Dublin, Sing Street is illustrious and welcoming. Kudos to the creative team who helped the production morph from screen to stage. These include: Martin Lowe (music supervisor, orchestration & arrangements) Bob Crowley (scenic & costume design) Christopher Akerlind (lighting design) Darron I. West (co-sound design) Charles Coes (co-sound design) J. Jared Janas (hair & makeup design) Fred Lassen (music director).

Sing Street is running at NYTW until 26th of January. See it for its music, performances and overall joie de vivre. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘London Assurance’ directed by Charlotte Moore at The Irish Repertory Theatre, a Rollicking Christmas Treat

(L to R): Colin McPhillamy, Elliot Joseph, Caroline Strang, Rachel Pickup, Robert Zuckerman, Evan Zes, Meg Hennessy, Brian Keane, Ian Holcomb, ‘London Assurance, by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

London Assurance, the vibrant farce by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore at the Irish Rep is the perfect production for the Christmas season to keep the cheer bright. The acting is superb, the pacing of high jinx is acutely shepherded by Moore. Altogether, there is everything to like and enjoy and nothing to find fault with in this production which runs until 26 January.

A mix between a drawing room comedy and slapstick without the physicality but oodles of wordplay, Boucicault’s London Assurance also satirizes stock character types, social classes and the notions of marriage for convenience which were beginning to be blown away by the idea of love matches, at the time the play takes place Christmastime, 1841.

(L to R): Brian Keane, Colin MPhillamy in ‘London Assurance,’ by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

The action begins when dissolute Charles Courtly (Ian Holcomb) arrives with his friend Dazzle (Craig Wesley Divino) in the morning hours after a night of hard drinking and partying. Charles lives with his father Sir Harcourt Courtly (Colin McPhillamy is perfection as the fop who is easily duped by his own puffery). Courtly believes his son to be the innocent, demure, hard-working student who eschews gambling and drinking. Charles is the antithesis. Servant Cool (Elliot Joseph) lies to protect Charles.

(L to R): Meg Hennessy, Caroline Strang in ‘London Assurance,’ by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

After Dazzle and Cool carry Charles off in a drunken stupor, Sir Courtly enters in his dressing gown wishing for his breakfast. Courtly reminds Cool of the recent most important events of his life. He and his friend Max Harkaway (the fine Brian Keane) have arranged for the elderly Courtly’s marriage to Max’s young, beautiful niece Grace (Caroline Strang) in exchange for an obviation of debts, and her dowry. If Courtly or Grace nullifies the arrangement, Grace’s money will be Charles’ inheritance.

The arc of development involves the foiling of Courtly’s plans when all visit Max’ country estate in Gloucestershire where Courtly is supposed to finalize his engagement to Grace. Max has invited Dazzle and of course Dazzle brings along Charles for the adventure and fun the visit promises to be, though Sir Courtly doesn’t realize that Charles has joined the party. At Max’ estate, Grace meets a disguised Charles who poses as Augustus Hamilton to dupe his father who believes him to be home studying. Both Holcomb and McPhillamy pull off the bad disguise non-recognition and Sir Courtly’s dubious response to his son’s “lookalike” with great humor.

Caroline Strang, Ian Holcomb, in ‘London Assurance,’ by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Charles, ever the playboy, flirts with Grace unaware that she is his future mother. For her part Grace is sanguine about marrying Sir Courtly, but falls in a hot love with Charles. What are they to do? How can they put off Sir Courtly and Uncle Max Harkaway and effect their marriage to each other? By this point in the plot the playwright has drawn us in for Sir Courtly is no particular catch and to American audiences today, the idea of a woman having to drop her dowry in the lap of an elderly gentleman in order to survive is almost unthinkable, especially when the marriage has been arranged for her.

In the succeeding scenes we meet the lovely friends of Max, Lady Gay Spanker (the wonderfully comedic Rachel Pickup) and her ancient-looking husband Adolphus Spanker (Robert Zukerman draws many laughs with his outrage about his wife leaving him) who is vital, spry and a force of nature that Lady Gay Spanker loves as her protector. However, when Charles beseeches Lady Gay for her help to dissuade his father from sealing “the deal” with Max for Grace, Lady Gay thinks of a humorous idea to break up plans of Sir Courtly’s marriage.

Rachel Pickup in ‘London Assurance, by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

In great good fun she seduces the pompous Sir Courtly to fall in love with her behind her husband’s and Grace’s back. Sir Courtly who believes himself to be twenty years younger and on the cutting edge of fashion, is tricked by Lady Gay. He rushes after her to win her kisses and affection. Of course, when Spanker hears that his wife may separate from him, his reaction is hysterical. Meanwhile, Lady Gay is having the time of her life in harmless fun to help out two young lovers who doubt each other’s love. The complications rise and Lady Gay works her miracle for a good cause, until…

This is no spoiler alert. You will just have to see this humorous LOL production to appreciate how the playwright adds complex and humorous twists to the relationships and magnifies mishaps and errors raising the stakes and jokes to a delightful climax with a duel.

Colin McPhillamy, Rachel Pickup in in ‘London Assurance, by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

Charlotte Moore’s sense of comedic timing, what does and doesn’t work has been engineered to a fine froth so that the actors appear to be these authentic, vivacious, funny individuals. I cannot imagine Colin McPhillamy, Ian Holcomb, Rachel Pickup, Robert Zukerman, Caroline Strang, Evan Zes (the funny conniving lawyer) Brian Keane, Craig Wesley Divino, Elliot Joseph and Meg Hennessy sounding and behaving any differently in real life than they do onstage. Their performances are stunning. Their timing is spot-on.

Interestingly, the cast has managed to portray their characters so that they are not “the types” they appear to be, but are funny because their traits are humorous. Evan Zes as the “sneaky, obtrusive” lawyer Mark Meddle dismissed by Meg Hennessy’s “go-to-girl” Pert, with the accusation of “slander” is an example. In the hands of these actors this is accomplished with seamless effort. Additionally, the actors handle the asides to the audience with an easy, intimate confessional tone that enhances the comedy. Finally, we enjoy the foibles of each character whom the actors have invested in with their perceptive, canny skills.

Robert Zuckerman, Evan Zes in ‘London Assurance, by Dion Boucicault, directed by Charlotte Moore, Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg)

The sets sparkle with beauty and apparent luxury thanks to James Noone’s scenic design. The interiors are befitting of what one would expect of Sir Courtly’s and Max’s residences. Likewise, Sara Jean Tosetti’s costume design and Robert-Charles Vallance’s hair designs authenticate the period and social status of the characters with excellence. Lady Gay’s purples (I loved her costumes that reflected her expansive, lively character) matched with a lighter shade of purple for her husband’s cravat (?). As a couple they reflected a refined, spiffy, fascinating dynamic. Indeed the creative team’s techniques and strategies inspired by Charlotte Moore’s vision for the production were not overblown, but were “a Goldilocks.” Rounding out the team are Michael Gottlieb’s lighting desgin and M. Florian Staab’s sound design. The music was lighthearted and chosen for the splendid mood of the production.

Once again Irish Repertory Theatre proves its stalwart magnificence for the season with this marvelous comedy that Charlotte Moore, the ensemble and creative team have imbued with their joie de vivre and experience. If you don’t see it, you will have missed a special production. London Assurance runs with one intermission until 26 January. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Jagged Little Pill,’ on Broadway is Electric, Dazzling in Its Power, Scope and Complexity

Celia Rose Gooding, The Company, in ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

Alanis Morissette’s album “Jagged Little Pill” reached the stratosphere as one of the best selling albums of all time almost twenty-five years ago. The reason is clear. In its contradictions, biting satire and themes it resonated with its global audience, topping the charts in 13 countries worldwide. With that appeal behind it, the notion that the music might land in a stage production was a given, especially if a superlative writer could write an exciting book so the right director would then eventually shepherd the production to Broadway.

And so it happened. Diablo Cody, multiple award-winning writer of the film Juno (2007), synchronized her sardonic fresh, perspective with Morissette’s bile-dripping, alternative rock songs featured on the 1995 album. The meld effected the gyrating musical that premiered at American Repertory Theater, Harvard University in 2018, exquisitely and brilliantly directed by Diane Paulus. The creative team’s synergy further transformed the production into the present dynamo which opened at the Broadhurst Theatre in early December.

How is the musical Jagged Little Pill not just another teenage-angst-driven-juked-up melodramatic foray into identity, social acceptance and self-love? The glossy superficiality of the pumped up, unmemorable, alternative, post-grunge, pop rock light, the stuff that “OK” musicals are made of, is nowhere to be found in Jagged Little Pill. This is because of the grainy, raw vitality of Morissette’s and Glen Ballard’s music, supervised, orchestrated and arranged by Tom Kitt, with additional music by Michael Farrell and Guy Sigsworth.

(L to R): Celia Rose Gooding, Derek Klena, Elizabeth Stanley, Sean Allan Krill, ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

On the contrary, the production, that some affectionately liken to a jukebox musical, defies that definition. First, there is its particularity. It is hard-edged and profound; the arc of Cody’s story spirals and complicates as she lays bare the Healy family while satirizing the underlying mores of the tony community where they live. Additionally, the finely tuned characterizations penetrate with authentic details. Their development draws us into the realm of gnawing secret addictions and the currently overripe, hellish thrall of Oxycodone, brand name OxyContin.

Whether we know of the relentlessness of this drug from experiences of friends, family members, neighbors or ourselves, we empathize with the characters as they confront its lethal power in a felt irrevocability. We’ve seen countless news stories and films on the subject, like the HBO documentary This Drug Can Kill You (2017). We’ve heard of the extremities of addiction resulting in the destruction of family bonds, the tenor of which Cody examines through the characterization of mother Mary Jane Healy her protagonist.

Celia Rose Gooding, The Company, in ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

And what of the story of the wife and mother who broke her arm and kept on breaking it to justify prescriptions of oxycodone? Typical of addicts desperate for the opioid. Prescription meds addicts even have committed robbery and murder. (See article on David Laffer) Of course the drug should be taken off the market and banned but big pharma would lose money in its profitability; addicted middle and upper class women can afford to pay. Why give up on a good thing even when doctors now curtail its use which pushes addicts to the street where they buy OxyContin laced with poisonous Fentanyl for the trip of a lifetime?

Why don’t such individuals “get help” especially when they can afford it? Indeed! Help is the last step in the journey of the addicted. It implies that the family interacts with each other because they must be the main support system of the addict. Cody’s Healy family members do not interact much. They live quiet lives of desperation, seeking their own “thing” when we first meet them, though by all appearances from their home, to their lifestyles to their social connections, these folks “have it together.” Even adopted Frankie Healy (the spectacular Ceila Rose Gooding) is a mess, though you would never suspect it, because she asserts her powerful personality as a young, black woman who is assured in her gay relationship with Jo (the adorable, rockin’ Lauren Patten who sings Morissette’s signature number “You Oughta Know” to a standing ovation).

Lauren Patten, The Company, in ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

How are the posted social media photos of the Healys as the smiling, joyous family fakes it? The image is more important than the reality. And if the image looks good enough, maybe the family members will believe it’s true. How can we fault them at the time of Trumpism, when the president and his family and his supporters do the same, sporting the “best” of everything, from perfect presidential behavior, to perfect relationships with his staff, who are loyal to him because he is filled with grace? Such perfection has not been seen since the “savior.” Likewise, the Healy family’s “perfection” in the view of their friends and neighbors is non-pareil.

The Healys, as representatives of most suburban middle families, traffic in mendacity though such cowardice destroys. As it turns out, lying is the mother of addiction. And addictions salve the soul. With pornography, sex, oxycodone, adderall, alcohol, heroin, etc., life’s miseries become doable and for a time “everything is beautiful.” Of course such duplicity can only go on for so long before the veil is ripped and the ugliness shows through. In the production the songs “All I Really Want,” Hand in My Pocket” and “Smiling,” clue us into the lies. However, the family keeps their secrets from each other until there is a turning point acutely rendered at the end of Act I during the songs “Wake Up” and “Forgiven.”

(L to R): Elizabeth Stanley, Heather Lang, ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

The growing divide in each of the characters eventually earthquakes. The one who is the glue holding the family together, perfect mother and wife Mary Jane (the gobsmacking Elizabeth Stanley) gets shaken to her core. The precipitating factor is oxycodone, but Mary Jane’s issues run silent and deep. The drug only suppresses and numbs her from acknowledging the soul gnawing canker worm that eats away at her image of perfection while she bleeds like an open wound inside.

As the musical follows the unraveling conflicts between Mary Jane and husband Steve (Sean Allan Krill) son Nick (Derek Klena) and adopted daughter Frankie (Gooding), other hot button issues come to the fore sweeping the family up in their detritus. These include but are not limited to our paternalistic rape culture, Evangelical Christianity’s homophobia, pornography addiction which deadens intimacy between couples, and black-white cultural bias to name a few.

Nora Schell, The Company, in ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

In the well crafted book, music and thoughtful lyrics, Cody and Morissette reinforce an ancient folkway of family structure; there often is little communication beyond functional superficialities. Sadly, profound communication belies self-awareness and soul authenticity. In such a family unit where obfuscation and a general lack of will to work together as a family become routine, addiction is easy. Finding a life worth living individually and with one’s family becomes impossible. The “impossibility” impinges on the family structure and each individual family member as the situation worsens for all.

And so it goes for wife Mary Jane and Steve. Though Steve does make an attempt to reach out to her, she rebuffs him. So it goes for Nick, the “perfect” son (Klena’s rendition of “Perfect” is excellent), who lives out his parent’s dreams not his own, and for Frankie, who is “all that” proud. Each self-deceives. Each is distracted by the race for perfection and by their manic avoidance of failure and the recognition of their faults, which comprise their endearing humanity. In fearing the stigma of being a “loser” (each family member defines it differently and never discusses their own perceptions until the end), each launches off into their own journey of error which impacts the family as a whole. When they become aware of their self-delusions (the exceptional song “Wake Up”), it is a boon that they and other characters come to grips with by the play’s conclusion (in the song “You Learn”).

Derek Klena, The Company, in ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

Whether rich or poor, young or old, life is learning, and of course with learning comes change, pain and reconciliation. But first as the linchpin of the family, Mary Jane experiences the long and grueling events in her relationships. She begins first with her addicted alter-ego, then her children and husband. Through trial and error she learns to explode the self-deception, lies, defensiveness and powerlessness conveyed to her family, who become estranged from her as she embraces the drug as her panacea (this is terrifically rendered in movement during the song “Unforgiven”).

But before any of the family learn that their arrogance and attempt at perfection is delusion, they have to be awake to register they are fantastical creatures on a racetrack toward oblivion. The wonder of Cody’s book is that she has Steve and Nick on the road to awareness before Mary Jane, and Frankie who is blinded by her interest in Phoenix (Antonio Cipriano), which destroys Jo (“Your House”).

Derek Klena, The Company, in ‘Jagged Little Pill,’ book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

We note the disintegration of Mary Jane’s soul, whose behaviors are out of the addict’s playbook. Elizabeth Stanley crafts her characterization with nuanced sensitivity and empathy. She inhabits the ethos of the addict as the drug’s deadly chemicals subvert her being. Stanley is in the moment, from moment to moment with her lyrical voice and nuanced devolution. Our concern and identification with Mary Jane is elicited by Stanley’s prodigious talent.

The same may be said for the actors who inhabit the family members: Ceila Rose Gooding’s Frankie- activist and hypocrite blind to her own foibles; Sean Allan Krill’s loving, caring husband who stands by Mary Jane and reveals he wants to help her become well ( “Mary Jane”), though he is a “work-a-holic” and has an addiction to pornography and masturbation.

Cody has rounded out these characters and the actors thread their depth through the eye of the acting/singing needle. All have gorgeous voices. No less talented is Derek Klena. Klena’s emotional crisis (whether to jeopardize his life path and testify to a rape he saw or keep it a secret along with his unhappiness living his parents’ goals for his life), is heartfelt. Initially, it is Nick who sounds the alarm about his family; Kitt’s orchestrations manifest this twice in a long note from a brass instrument (is it an A or C?), almost like a harbinger that a turning and reckoning must happen or they all will be immeasurably harmed.

Elizabeth Stanley, The Company,Jagged Little Pill, Diablo Cody, Alanis Morissette, Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

Paulus’ staging and her vision, and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s movement to evoke the characters’ emotions are smashing. The characters’ inner rage and torment and Mary Jane’s double mindedness about her addiction’s seduction and her love of self-destruction (“Uninvited”), are clarified in the movement and the dance. Paulus has staged the characters in various scenes so that they are propelled in circles using the props (desks, walls). The effect reveals their confusion and inability to straighten out and to seek emotional life paths that are not dead ended in circularity. Paulus/Cherkaoui also integrate break-dance movement with the songs as a metaphor, representing the emotional inner churning and rage of the characters. Paulus makes sure that the character rage and their emotional circularity are cogently integrated with Riccardo Hernandez’s scenic design and Justin Townsend’s lighting design.

The Company of Jagged Little Pill, book by Diablo Cody, music by Alanis Morissette, directed by Diane Paulus (Matthew Murphy)

The frame of the house in lines of light in various colors abides throughout. Its symbolism recalls how the structure of family and home and what family members experience there, is carried everywhere into relationships, into school, into work, into social activities. Justin Townsend’s lighting design is effective as it is used to reflect emotions. For example, Jo’s fury in “You Oughta Know” is aligned with Townsend bathing the stage in red. Patten’s Jo is fabulously wild; the injustice she feels about Frankie’s demeaning mistreatment is a show stopper made all the more wonderful by Townsend’s lighting and Cherkaoui’s movement.

Additionally, “Wake Up,” and “Forgiven” (as the family members’ backs to the walls of their own making spin them around), are particularly stunning. In these numbers and in “Predator,” “Uninvited” and “Mary Jane,” Paulus, the company and creative team pull out all the stops. And “No” by Kathryn Gallagher as Bella (she has been raped by Nick’s friend), singing with the support of the company, should be taped and played for every Sex Ed. class in high schools: the signs are especially noteworthy.

At its heart Jagged Little Pill is about family. It is provocative, in your face, striking, salient. If one considers how easy it is to couple and how hard it is to move toward a kind, generous, integrative family who works on their failures by loving in overdrive, Cody’s Healy family, portrayed in its jaggedness is a superb textured unit. As a key theme, there is always hope for redemption and reconciliation, Cody suggests, for them, for us.

Add Alanis Morissette’s music, with Kitt’s orchestrations, Paulus’ metaphoric, symbolic staging, the amazing performers, the lighting and brilliantly minimalistic and always seamless and mobile scenic design, Jagged Little Pill is a musical worthy of the nearly twenty-five year wait for these creatives to bring this sterling production together. It is the right season for Jagged Little Pill to take flight with this cast, Cody’s sheer audacity and Paulus scaling the mountaintops of her craft.

I’ve said enough. See it with your eyes wide open and enjoy it awake. It is an experience you won’t easily forget. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘One November Yankee,’ Starring Harry Hamlin, Stefanie Powers at 59E59 Theaters

Harry Hamlin, Stefanie Powers in ‘One November Yankee,’ written and directed by Joshua Ravetch at 59E59 Theaters (Matt Urban)

One November Yankee the comedy written and directed by Joshua Ravetch sports an intriguing structure. The play is four scenes: a flashback and a flash forward framed by beginning and ending scenes between a brother and sister that take place at MOMA. This is where art curator Maggie and modern artist Ralph are putting the finishing touches on Ralph’s art installation. The play is about siblings, different pairs in each of the scenes played by Stefanie Powers and Harry Hamlin. Each pair of siblings with a combination of love and rancor face-off against each other with humor, with pathos. Eventually, they resolve their differences. With one pair the resolution has an unusual twist.

As the production opens Maggie and Ralph argue about Ralph’s art work. Maggie avers with sarcasm and witticisms about what the project stands for and what it is. In the center of the presentation area is a “tangled mangle of debris,” that appears to be a yellow Piper Cub that has crashed in the woods. We later discover the installation has a basis in truth. Ralph has entitled his piece “Crumpled Plane,” to exemplify his social criticism of a “Civilization in Ruin.” Maggie, who has helped to bring money in to fund the project is not “thrilled” with Ralph’s work.

The quippy thrust and parry of their argument is well-crafted with bits of irony. Harry Hamlin who is Ralph, and Stefanie Powers as Maggie carry off the coolness and chic of these well-healed characters with fine-tuned humor and aplomb. What becomes intriguing are the references and through-lines Ravetch establishes about the three different brother/sister relationships. These are picked up in the next scenes (a flashback, and flashforward to the present) and are cleverly related as we watch how the sibling pairs collaborate to make the best of difficult situations.

Harry Hamlin in ‘One November Yankee,’ written and directed by Joshua Ravetch at 59E59 Theaters (Matt Urban)

In the initial play frame Ravetch introduces the metaphor and thread of flight. Maggie describes how she is forced to fly Jet Blue coach (something which she never does) to get to New York and be present for Ralph’s exhibition. Is it a premonition of what she will be able to afford when Ralph’s exhibition doesn’t get off the ground? Perhaps. After being diverted to Philly because of bad weather, Maggie’s only recourse is to fly on a puddle jumper to Vermont where she must take a Greyhound to NYC. The puddle jumper thread hits home when she confronts her brother’s art installation, a smashed yellow puddle jumper with a forest behind it. This crashed plane symbolizes the possibility of another “crash,” the crush of negative critical reviews of Ralph’s art installation which may lead to the loss of Maggie’s job and the end of her career.

During the course of Ralph’s attempt to defend his work against Maggie’s jibes, he references their relationship to the one of the brother and sister who went missing after the plane crash he’s attempting to effect through art. This crash and the other hundreds of plane crashes which occur over the U.S. and which he represents with this artistic endeavor, complete with videos of the Wright Brothers, “flying machines” of old, and the journey of the yellow Piper Cub has great meaning for him. His art mimic’s life’s art, and as in much of the play is a facsimile to what has happened and will happen.

Ralph explains that his exhibit symbolizes how the expected “glorious” future which began with the Wright Brothers and promised “flying cars,” convenient monorails in suburban settings and an end to traffic jams has devolved into the decline and a “Civilization in Ruin.” What “began at Kitty Hawk, ends here in this room,” he suggests. That this is an overblown, self-important, humorous notion which Hamlin as Ralph delivers as a serious pronouncement is ironic as Power’s Maggie calls him on it. She responds to this and his defense of his work with sarcasm. Eventually she lands on the subject of her birthday which she spent alone without him because he forgot, another possible reason why she is so edgy.

Harry Hamlin in ‘One November Yankee,’ written and directed by Joshua Ravetch at 59E59 Theaters (Matt Urban)

Obviously, this brother and sister vie between being close as siblings and rancorous as rivals. The scene ends with Ralph playing the video of the Yellow Piper Cub’s journey as Maggie reads the article about the brother and sister lost in the mountains of New Hampshire five years prior. As the plane on the video flies into the flashback, Ravetch unspools what happened to the next brother and sister pair as they attempt to negotiate their downed plane that appears the same as Ralph’s artwork.

In the next scene Powers and Hamlin play Margo and Harry who sport different demographics than the first couple revealed in their dress, manner, hair and speech patterns. Both sets of siblings, however, are Jews and the humor connected with this gets a laugh, with the fine pacing and dead pan delivery by Hamlin and Powers. We discover that it is Margo’s carelessness that has brought about the crash which becomes more dire as time progresses for they are unequipped for the cold with no provisions and no functioning radio communications or beacon to signal where they are. Furthermore, Harry is injured and cannot walk out of the woods.

The second pair of siblings relate bits and pieces of their life and annoyances they’ve had with each other as they attempt to figure out what to do, for example, whether to wait for rescue or attempt to save themselves. References that Maggie and Ralph made in the framed scene five years later are eerily appropriate and tie in to the interactions of Margo and Harry. The space/time continuum melds somehow with the plane crash and the playwright suggests that each male/female sibling relationship has commonalities in a family dynamic that is relatable and empathetic. Ravetch is playful in drawing the similitude of characterizations. However, as the parallels and detail threads coincide, there is also a haunting and poignant tenor that we are seeing something profound in all of humanity.

Stefanie Powers, Harry Hamlin in ‘One November Yankee,’ written and directed by Joshua Ravetch at 59E59 Theaters (Matt Urban)

One overriding question remains. Did Ralph decide to create his artwork of a disaster which occurred to Harry and Margo because of some ethereal reason? Why has his imagination been so stirred? As we leave the second set of siblings facing the dark and cold, we are left with Margo’s indecision to stay or leave to find rescuers. The scene ends as they sing a song from the past to comfort each other as the evening of cold closes in.

The third scene flashes forward to the setting of the plane crash in present time, the same month as the Ralph’s art opening which has been inspired by Margo and Harry. In this scene part of the mystery is solved by hikers Mia and Ronnie, again portrayed by Powers and Hamlin, who stumble upon the crash. These siblings, too, parry and thrust and yield prickly comments, merging discussions of the past issues as they search the area and find clues to what happened to the passengers. Again, Ravetch conveys similar elements and threads from the previous scenes and drops them in the Mia and Ronnie scene weaving a fabric of relationships. Mia and Ronnie discover what is left of one of the siblings, whose body is now a skeleton. Of course they must alert the authorities to see what happened to the other sibling

The scene shifts once more to MOMA. Maggie and Ralph capstone their relationship, face the music and the former reading of the plane crash segues into Maggie reading aloud a critical review which is priceless. The last tie in is to the real crash site which is evocative and the final mystery about the missing sibling.

The fun of the production is watching how Powers and Hamlin portray with lightheartedness and authenticity three sets of siblings during the backdrop of dealing with “One November Yankee,” the name of the Piper Cub. As it turns out, the title of the plane, too, is symbolic. The set design by Dana Moran Williams is ambitious and Kate Bergh’s costume design suggests the differences among the siblings. Lighting design by Scott Cocchiaro and sound design by Lucas Campbell help to execute Ravetch’s vision for the production.

One November Yankee is 90 minutes with no intermission. It runs at 59E59 Theaters through 29th of December. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘The Half-Life of Marie Curie,’ Lauren Gunderson’s Work Uplifts With Brilliance and Currency

(L to R): Franesca Faridany, Kate Mulgrew, The Half-Life of Marie urie, Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

Iconic Madame Curie, the two-time Nobel Prize winner in the fields of chemistry and physics, was told by the committee awarding her prize the second time that she shouldn’t show up in person to receive it. She was having “women’s troubles,” we learn in Lauren Gunderson’s The Half-Life of Marie Curie, directed by Gaye Taylor Upchurch. The play is a profound and humorous evocation of the close friendship between Marie Curie (the magnificent, in-the-moment Francesca Faridany) and Hertha Ayrton (the equally magnificent, always present Kate Mulgrew). Ayrton, the British engineer, mathematician, physicist and inventor, was a suffragette and a celebrated genius in her own right. She paired as the perfect friend to Curie and helped her when Curie was at a nadir in her life.

Gunderson’s play whose setting is in Paris and England, reinforces the importance of women’s preeimence in the cultural flow of ideas in every field of endeavor. Furthermore, it highlights how folkways about women’s relegation to second class citizenship was a socially defeating, nihilistic ethic for the advancement of women and especially for the advancement of men. Gunderson reveals how Curie triumphed over the most antiquated of mores, especially after she loses the security and probity of her husband status in society after his death.

Franesca Faridany, ‘The Half-Life of Marie urie,’ Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

In her collaboration with husband Pierre both made ground-breaking discoveries identifying and naming polonium (after her native Poland) and radium. They coined the word “radioactivity,” to list a few of their accomplishments together. Curie’s work even after Pierre died established for all time that a women’s place was not behind the scenes as the little housewife, but could be in the forefront of the evolving scientific age. Curie, then and now, as is Ayrton, a beacon for all of us.

The Curies with Henri Becquerel received the Nobel Prize for their research on the “radiation phenomenon,” a prize hard won for Curie who was not nominated until a committee member and advocate for women scientists made a complaint to have her name added. Not only was Curie the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, she is the only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice. And she is the only person to win the Nobel Prize in two different fields, a feat no man or women after her has managed to accomplish. One shudders to think about the women who are being kept down by males and the internalization of this oppression by women as right and true. And this is advocated by men who cannot brook a female in leadership positions due to their own internal frailties and insecurities.

Kate Mulgrew, The Half-Life of Marie urie, Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

How life on this planet might have been very different if women were allowed parity in the professions for the betterment of society is anyone’s guess. After seeing Gunderson’s work and witnessing the dynamic she crafts between these two genius friends, one comes away encouraged, regardless of whether one is male or female. For a major theme is understanding the great and vital necessity of establishing collaborative efforts and parity between the sexes. As a detriment to all, the elevation of one to the suppression of the other, is a noxious practice which has been attempted with a political vengeance in our culture in the last three years. Such retrograde actions only result in horrific damage for both sexes, especially the elites who depend upon the “little people’s” consumerism. It must stop and Gunderson’s celebration of these two women as an exemplar in our culture and other influencers insure that it will, hopefully sooner than later.

(L to R): Franesca Faridany, Kate Mulgrew, The Half-Life of Marie urie, Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

Gunderson highlights these themes about gender parity opening her play at a crucial point in the life of Marie Curie after Pierre’s death. Curie might have succumbed to her “women’s troubles,” if not for the encouragement and intervention of Hertha Ayrton. Hertha offers Marie an infusion of love and affirmation of their friendship, as well as a refuge at her seaside home in England, where Marie may recuperate from her physical ailments and emotionally resurrect from the trauma of scandal.

The “troubles,” Gunderson relates during Ayrton’s exhortations to Curie to remain firm and solid to weather the scandal of Curie’s affair with married Paul Langevin, Pierre’s student and fellow scientist. The playwright subtly and with dynamism forms the arguments between the two women, one cowering, humiliated in despair, the other, a proud, indomitable scientist and suffragette strengthening her friend. During their back and forth thrust and parry, we discover important details. The dialogue is sage, clever, poetic, humorous with little exposition, all in the service of defining the wonderful, well-drawn characters most beautifully acted by Faridany and Mulgrew. The writing exemplifies how these women portray their care for each other acutely, as they take us into their relationship. As a witness to this, we are grateful to be watching and listening to their elucidating adages and poetic wisdom.

(L to R): Franesca Faridany, Kate Mulgrew, The Half-Life of Marie urie, Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

What has happened to Curie in light of her contributions to science can only be described as monstrous. Mrs. Langevin, suspecting that her husband was in a “love nest” with Curie, works to expose and destroy her. She hires an investigator who breaks into their apartment and finds incriminating love letters which prove their adultery and are subsequently leaked to the papers. The press engages in a smear campaign portraying Curie as a home wrecker and a seductive Jew (she wasn’t Jewish) as they feed into the xenophobia and anti-semitism of the time. In keeping with entrenched folkways, the papers portray Mrs. Langevin as the innocent, ill-treated victim of their betrayal. The real truth is somewhere in between as Paul Langevin actually improves his stature as Curie’s lover. We never discover his relationship with his wife and he comes off as the cavalier and romantic rogue whose “wife salvages hearth and home” belying her malevolence toward Curie.

Curie introduces herself to us paralleling her life to radioactivity. We hear lovely music then sounds of what will be identified as a demonstration. When Ayrton enters her apartment, she finds Curie in great despair. She and her children are held hostage in their apartment by the angry mob protesting in the streets demanding Curie’s censure for her whoredoms.

Franesca Faridany, ‘The Half-Life of Marie urie,’ Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

Ayrton makes her grand entrance with humor and vitality and gradually helps to stiffen Curie’s resolve not to allow the scandal and vituperations of the press to completely overwhelm her into depression and career death. During the course of the humorous back and forth, we discover how Curie’s life has been upended, her career and work halted, her daughters harmed by the nefarious publicity in which Mrs. Langevin is happily vindicated and justice applied through malign falsehoods. The fact that Mrs. Langevin, “the woman scorned” goes after her rival publicly when her husband is equally responsible and deserves as much of the public ire as Curie, is a sad fact of the cultural folkways. Either way, women lose. Certainly Mrs. Langevin needs the financial support of her husband. Thus, she attacks Curie the one who endangers her home manipulating cultural mores. Ironically, Langevin rather “has his cake and eats it too.” (We discover later his wife is pregnant.)

The gender conflicts Gunderson alludes to stem from the oppression of the patriarchy which controls every institution, and whose tentacles of power stretch globally. The double standards allowing men every freedom and women every restriction, especially with regard to sexual openness, Gunderson, through the voice of the ironic Ayrton lays bare. Enforced is the underlying truth that women, like children, must be silent, demure, passive, and above all, unemotional. Ayrton reinforces that this oppression must be undone with laws giving women the vote and ability to speak and stand for themselves autonomously for the greater good of society.

(L to R): Franesca Faridany, Kate Mulgrew, The Half-Life of Marie urie, Lauren Gunderson, Gayle Taylor Upchurch, Minetta Lane Theatre Audible (Joan Marcus)

Ayrton quips about how the culture deals differently with men when they have affairs. Men are lauded, encouraged for their virility. Women are character assassinated, labeled sluts, etc., especially when the man is younger. That Curie’s career is put on hold and she is stripped of almost everything including a place where she and her daughters can live in unmolested peace is a testament to the abysmal place of in the culture who are given no consideration. They are invisible, shunted to a no-where-land, chosen after last place, while men are foremost.

The clarity of the injustices of gender inequality are saliently pinpointed in Gunderson’s examination of Curie and Ayrton’s heroism. Their concerted efforts to combat the public’s outrage are admirable. Despite warnings to the contrary, Curie attends the Nobel ceremony, accepts her prize and makes a cogent speech all of which takes great effort. And that was just the beginning of the next chapter in the lives of both women, who worked together to help the soldiers with their discoveries during WW I, accumulating more intrepid achievements that would make anyone’s head spin.

This last chapter in their lives is poetically and poignantly rendered by Faridany and Mulgrew guided by Gaye Taylor Upchurch. The actors bring Gunerson’s words to life with radiance and potency so that these women become our endearing mentors. They reveal what is possible if one persists and stands against males in power who conduct smear campaigns and proclaim women have no place in their world. This is the great and irrevocable lie of fear and obstruction which cannot and will not stand. Like truth, parity, collaboration and the freedom to choose one’s own destiny before God is an inevitability that will increase for women encouraging them to shine their light so that others can see.

This is a sterling production which is so well-crafted and portrayed by the actors it is not to be missed. See it before it closes on 22nd December. The Half-Life of Marie Curie with excellently conceived scenic design by Rachel Hauck, costume design by Sarah Laux, lighting design by Amith handrashaker and sound design by Darron L. West is at Minetta Lane Theatre (Minetta Lane off 6th Avenue). For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ Starring Kristine Nielsen, Aidan Quinn

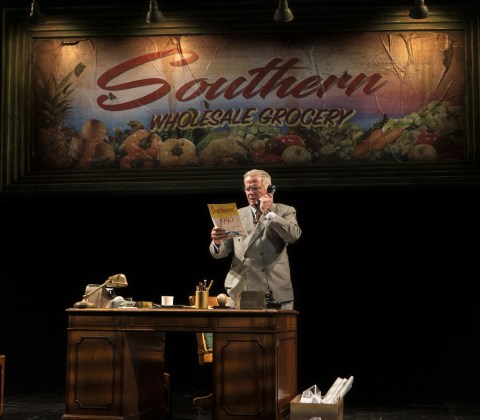

Aidan Quinn in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

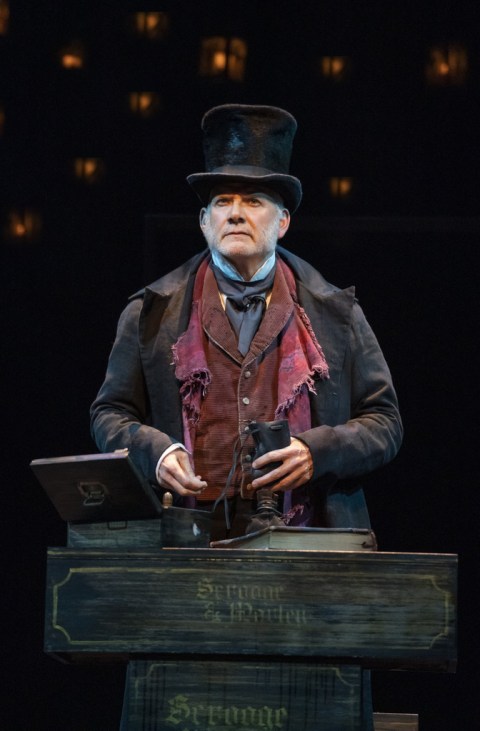

Horton Foote’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Young Man From Atlanta, directed by Michael Wilson currently in revival at The Signature Theatre is one of Foote’s homely plays exploring loss, alienation and quiet reconciliations. Kristine Nielsen stars as demure, sheltered housewife Lily Dale Kidder in an uncharacteristic turn away from the high comedy of Taylor Mac’s Gary (it’s a blossoming). Aidan Quinn is her husband, wholesale grocer Will Kidder whose security and success is upended in the twinkling of an eye by the end of the play’s first scene. With these prototypical characterizations, whose actor portrayals are shepherded with sensitivity by Wilson, Foote treats us to a slice of suburban Americana in a representative middle upper class dynamic as a couple confronts the unspoken and faces the unspeakable with poignancy and primacy to move together into the winter of their lives.

Aidan Quinn, Kristine Nielsen in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Foote opens the play at Will Kidder’s office where we identify Will’s assurance, ambition and success in his discussions with Tom Jackson (Dan Bittner) his assistant and underling in the company. It is an incredible irony and stroke out of left field that boss Ted Cleveland Jr. (Devon Abner) has appointed Tom to replace Kidder whom he fires because he is, in effect, “over the hill” and unaware of the new trends. However, during Tom’s friendly discussion with Kidder when we learn Will has built a new, expensive house perhaps to keep his wife busy and away from thoughts about their son who drowned, Tom is sanguine about his new position and Kidder’s impending doom. To his face he acts the innocent and only until Ted Cleveland Jr. tells Kidder he is fired and that Tom replaced him does the shock wear off and we realize Tom’s surreptitious nature.

Foote, the actors and Wilson allow us to think the opening is just an expositional scene, when in fact the playwright is laying down tracks to steamroll over his protagonists by its end and throughout the play. Inherent in the first scene we note the main themes of the play and character flaws: secrecy, disconnectedness, dishonesty, underhandedness, blindness, pride, insecurity and wobbly integrity.

(L to R): Aidan Quinn, Dan Bittner,’The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson, Signature Theatre

(Monique Carboni)

Quinn’s Kidder takes the news badly and provokes Cleveland Jr. to waive his three month severance because of his blustery, boastful comments about starting his own company. Quinn is superb in revealing the bombastic as well as quieter moments of the character. Indeed, Kidder’s frustration and annoyance that his life and career are taking a dive into the toilet and his life’s work has been abruptly shortened is portrayed with heartfelt, spot-on authenticity by Quinn.

The themes become magnified in the next scenes. Rather than confide in Lily Dale about his firing the moment he steps in the door, he hides the truth from her and attempts to face the trial of coming up with the money for the house and other expenses alone. Repeatedly, the couple reveal that they have lived “quiet lives of their own desperation” without confiding in each other. The excuse is that they do not want to upset each other, however, in their lies of omission, they upset themselves more and make huge mistakes which increase the pressure under which they live, pressure which results in Will’s deteriorating heart.

Aidan Quinn, Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

In the midst of this excitement are phone calls. It’s the young man from Atlanta who was the roommate of their deceased son Bill. Throughout the play, he is unnamed and remains a ghostly presence shading them with possible portents about their son’s life. Indeed, by not giving this momentous presence a name or face (he never materializes) he becomes a symbol of menace, of the lie that destroys quietly, of the deception that kills, of the unrevealed mystery that eats away at one’s soul from inside out. Unless and until Will and Lily Dale together deal with “the young man from Atlanta,” both protagonists will self-destruct. It is how they confront this spectre and what he is that propels the marvelous, tricky development of the play.

It is in the first scene that we are apprised of this “young man” in a phone call to Will’s office. Will refuses to speak to him. We sense there is an occult meaning as he calls again and then must be turned away. Foote keeps his mysterious presence looming in the background. Who is he, what does he want and why does he keep calling? Eventually, the material answers give clues to the play’s deeper meanings.

Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

As the conflict progresses and Lily Dale and Will stop speaking to each other we discover clues that Lily Dale and Will reveal almost prying out the truth from themselves for fear that hearing it they will break down. Quinn and Nielsen work together beautifully at the gradual exposure of the light as the dawn breaks in their souls. Fortunately, the light breaks on them at different intervals and doesn’t completely overcome them, though Quinn’s performance yields that Will hangs on the edge of darkness. He may collapse and die on Lily Dale. But Foote’s intention is not more tragedy, it is deliverance in the quiet moments when still, small voices murmur in the dark hours of waiting for the dawn.

Because this couple are there for each other in their weakest moments, we understand that though their marriage has had sustained rough patches through the seasons, the most devastating one being the loss of their son and the occluded reason why he died, they do have each other. And it is to each other by the end of the play, they turn for hope and solace as they accept what they cannot change and not regret too much that they weren’t on top of themselves and their own blindness sooner.

Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Rounding out the characters are Lily Dale’s stepfather Pete Davenport and his grandnephew Carson. As Pete, Stephen Payne gives a fine, humorous and measured portrayal of one who appears to be kindly and steady if not too discerning. Davenport stays with Lily and Will. In a particularly well suited scene that drew great chuckles from an audience who understood and had been there, the couple hits up Pete for money separately then together in an attempt to raise the funds to start Will in his own business. Davenport is cheerful and openhanded, but eventually, the fund raising plot explodes when Will goes to the banks and is refused loans. Left and right doors shut in his face and the money that Lily Dale had in her savings has been mysteriously depleted, though Will appears to have given her everything she needs for the new house.

The mystery of this continues until the truth spurts out from guilty consciences and we discover almost everything that has been hidden. As in life, though, there are some secrets only those who kept them know the answers to. However, it is Carson who unwraps the package of assumptions, lies of omission, hidden secrets and deceptions with his cheerful, unassuming presence which ironically also carries with it a hidden and secret component.

Aidan Quinn in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

Carson (Jon Orsini) appears innocent and charming. But the intrigue and conflict increases when Carson reveals he knew Bill’s roommate, the young man from Atlanta who keeps calling the house and upsetting Will and Lily Dale. Carson identifies negative elements about the lying character of Bill’s roommate. Afterward, continued revelations come fast and furious from Will who discovered he was taking money from Bill. He finally reveals this to Lily Dale to chide her to stay away from the young man. The deceptions, the manipulated lures of Bill’s roommate who Lily Dale sees as a lifeline to her dead son continue, until finally the couple confront what in 1950 Houston, Texas was unmentionable, if unthinkable.

As one who helps Lily Dale eventually get to that confrontation, there is the former housekeeper who took care of Lily Dale when she was younger. The dignified, lovely, elderly, black Etta Doris (Pat Bowie) is ushered into the new home by their efficient housekeeper Clara (Harriet D. Foy). Etta Doris is a symbolic character, and she comes with an ironic reckoning. In her elderly, lame condition she feels an imperative to see Lily Dale. She walks a great length to their new home after the bus can only take her so far. Etta Doris comments on the loveliness of the home, and then expresses her condolences on the loss of Bill whom she remembered when he was a child. It is this connection from the past that has an impact on Lily Dale and it is Etta Doris’ unction of her faith and good will that brings to bear a greater truth on Lily Dale, though it is not immediately apparent.

(L to R): Pat Bowie, Kristine Nielsen, Stephen Payne in ‘The Young Man From Atlanta,’ by Horton Foote, directed by Michael Wilson at the Signature Theatre (Monique Carboni)

In including Clara and Etta Doris as a reference to another class that was an integral part of the well being of Houston’s elite, Etta Doris is a loving and authentic individual who does not restrain herself from showing her care and concern for Lily Dale. That it is she that offers Lily Dale a remembered affection from the past is one of the vital breakthroughs in the play. With her quiet, vital being, Etta Doris brings that which strengthens Lily Dale to face the truths that Will confronts her with by the play’s end. In that confrontation, Lily Dale and Will must cling to each other and resolve to live with the hurt and pain of their own imperfections. And they must hope that their shared truth will continue to reconcile them to each other and make them stronger, more loving, connected individuals.

The Young Man From Atlanta thanks to its strong ensemble work and fine direction by Michael Wilson resonates as a play of great humanity and truth that is deserving of its Pulitzer. With Jeff Cowie’s scenic design, Van Broughton Ramsey’s costume design, David Lander’s lighting design and John Gromada’s sound design and original music, Wilson’s vision is realized.

The production will be at the Pershing Square Signature Center until 15 December. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘A Bright Room Called Day’ at The Public, Tony Kushner’s Haunting Spectres Thread Through Hitler’s Berlin, Reagan’s 1980s and Trumpism

Nikki M. James, Michael Esper in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Tony Kushner’s A Bright Room Called Day directed by Oskar Eustis, currently at The Public until 15 December (unless it receives another extension which it should), reflects upon humanity confronting evil that on a number of levels appears unstoppable and irrevocable. Throughout the main action and play within a play, Kushner makes clear that those who recognize evil’s force and preeminence, often are too afraid to lay down their lives to fight, though fighting is the action needed to stop wickedness in political, social and economic institutions not constrained by the rule of law.

Nikki M. James in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The play uses at is jumping off point political and social issues undermining the Weimar Republic in Berlin. The setting encompasses events one year prior to the “Eve of Destruction,” when Hindenburg acceded to Hitler’s government take-over after which Hitler evicted parliamentary, constitutional democracy from the minds, hearts and souls of the German people. Kushner examines the parallels of that time with our culture during Reaganism and Trumpism.

The questions he raises are pointed. Some might argue that from the 1980s to now, the decline in our democratic processes and the public’s response appear similar to the public’s response to precursor events in Germany 1933. A Bright Room Called Day relates Berlin, Germany 1933 to 1985 Reaganism, devolving to the time of Trump. These three settings represent a turning point when the crisis of the period might have shifted in another direction if good citizens acted differently, affirming the adage, “evil flourishes when good men and women do nothing.” In this play Kushner examines the “What if?” Couldn’t citizens have halted the terrifying dissolution of democracy? Couldn’t they have liquidated Hitler’s fascist dictatorship before he even attempted to manifest his warped vision of the Third Reich’s reign for 1000 years?

Michael Urie, Nikki M. James in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The community of individuals we meet at the outset of the play who pop in and out of Agnes Eggling’s (Nikki M. James) lovely apartment are members of the political, liberal left, a combination of artists and activists who are/were at one point communists, socialists, progressives and union activists, one of whom is a homosexual (played by the exquisite, always present Michael Urie). All of these will be consigned to Hitler’s enemies’ list if they remain in Berlin. If captured, they will be deported as state enemies and undesirables and murdered when Hitler constructs and augments his network of slave labor and extermination camps to implement his “Final Solution.”

Kushner’s work which was excoriated when it first premiered in the 1980s has been given an uplift with an additional character, and dialogue tweaking to reference the current siege of Trumpism on our democracy. Kushner posits that our times manifest “inklings” similar to those employed by fascists and Reagan’s corrupt conservatives who sent the nation on a downhill slide which Trump appears to be pitching over the edge into oblivion, unless we do something. By drawing comparisons, we are forced to reflect upon the upheaval in our democratic institutions as the political, economic and social divisiveness spurred by Trumpism augments.

Kushner interjects his own commentary as a playwright and interrupts the action during which he actively engages his audience as a silent character whose consciousness he manipulates. Through identification with the people and events in Germany, we, like they, become like the frog that is placed in a pot of cold water. As the heat is turned up to the boiling point, if the frog is alert, he can escape before boiling to death. But he must realize immediately what is happening, so he will not be too lamed to escape. By degrees the audience realizes that they are in a crucible like Kushner’s characters, under which a fiery truth blazes. To that truth Kushner posits, one must recognize it, or its heat and pressure will pitch one into a death-state of paralysis like Agnes’.

Crystal Lucas-Perry in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The play’s new character is Xillah. Xillah represents Kushner’s perspectives as a citizen playwright who comments on his play and the policies of Reaganism and Trumpism. Playwright Xillah engages with Zillah his indefinable character whom he’s written into the 1980s. Zillah complains to Xillah about her function in the play. She importunes him for a viable role and purpose. She wishes to step beyond ranting about the emotional paralysis of character Agnes. Watching Agnes frustrates Zillah, for Agnes does little but quiver in fear at the ever-worsening events in Berlin. It is her fears which manifest nightmare presences (Die Älte-the Old One, in a wonderful portrayal by Estelle Parsons) who haunt her and drive her into soul paralysis which will lead to her death under Hitler’s regime.

Estelle Parsons in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Xillah, a character in the play framing the Berlin events is portrayed with humorous vitality by Jonathan Hadary. His character criticizes the activities by the cults of Reagan and Trump. He sardonically characterizes Reagan’s presidency and Trump’s “monolithic” personage with abandon in a stream of hysterical epithets that are right-on. Both Xillah and Zillah (Crystal Lucas-Perry is Hadary’s counterpart in a feeling portrayal) comment on the dynamic of the Berlin characters which Xillah (as Kushner) has created. They watch as Agnes, Paulinka (the superb Grace Gummer) Baz ( Michael Urie) Husz (Michael Esper) Gotchling (Linda Emond) and comrades Rosa Malek (Nadine Malouf) and Emil Traum (Max Woertendyke) grow morose and desperate, experiencing the dissolution of the German Republic into fascism. They palpably encounter the manifested evil of the time in the form of Gottfried Swetts (Mark Margolis humorously intrigues in his portrayal). He is the Devil, whose darkness overtakes Germany as Hitler ushers himself into the government and eradicates any goodness that went before.

Kushner’s characters argue about communism, socialism, democratic socialism and the state of affairs. Their discussions fuel their waning activism and encourage impassivity with a few exceptions, for example, Gotchling (Linda Emond), who is continually putting up posters which are torn down continually. We empathize with the Berliners as they react to the brutalities and street fighting, Hindenberg’s ending the government and the Reichstag fire which Hitler blamed on the communists to ban the party, arrest the leaders (his enemies), and consolidate his power base.

The characters react emotionally with disgust and outrage but their impulses to act are largely stymied by fear. They will not move beyond marches and protests that the Brown Shirts help to render bloody and ineffective. And when back room deals are made to put Hitler in power, they become powerless. Like many they appear to believe the propaganda rallies that show support for Hitler, though initially these are largely staged until the rallies gain in momentum and many join Hitler’s party.

The historical events are chronicled with vitality. The characters reveal poignant moments expressing the mood and tenor of the like-minded populace. Baz relates a story of a man’s suicide and his imagined wish to take one of the oranges, he, Baz, has purchased and give it to the dead man as a comfort. Of course, Baz never gives him the orange, but he imagines having done it, ironically comforting himself as the man is beyond being comforted. For Baz it is a horror seeing the dead man’s body pooling blood around it. Baz identifies the cause of the man’s suicide as the despair and immobility to stop the terrible events in Berlin. The suicide rocks Baz to the core. We align the man’s suicide with Baz’s suicide attempt which he stops himself from committing when instead, he has a sexual encounter. Baz’s choice is ironic and the impact of the suicide he witnessed in the streets is nullified by sexual distraction. As Baz, Urie delivers another incredible story later on which sets one reeling. Again, when Baz could take a stand, he chooses not to. Throughout, Urie’s performance is spot on amazing.

(L to R): Jonathan Hadary, Nikki M, James, Crystl Lucas-Perry in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

In the “intervening” frame play, Zillah attempts to persuade Xillah to write her with character powers that transcend time and space and go back to the past to warn Agnes of the danger of embracing fear and doing nothing. Zillah is upset that Agnes is so overcome, she is zombie-like. One of the humorous parallels is that Xillah, too, is at an impasse (like Agnes) only it is about the direction of this play and how to make it more vital so that it will have a resounding impact on the audience and get them to act. But he is filled with doubts about the function of plays. Also, he fears tampering with what he has already written. Indeed, he could make his play into a worse failure. His quandary is humorous.

Kushner, the frame (the present and 1980s) around which houses his Berlin character dynamic has Xillah remind Zillah of a number of important details, in addition to the chronological events of Hitler’s takeover. As Xillah parallels the then with the now, he affirms that friends living against the backdrop of Trumpism suggested he revisit The Bright Room Called Day because it is prescient and current. Xillah wrangles how best to show the similarities and complains that the characterization of Zillah doesn’t work. However, the character very much integrates the parallels. She criticizes inaction when a nation’s political/social structure disintegrates because the populace becomes overwhelmed and doesn’t act, becoming paralyzed as Agnes is paralyzed. The question remains: how does one move out of paralysis and take effective action which will change things for the better?

(L to R): Crystal Lucas-Perry, Jonathan Hadary in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The threads of alignment that Kushner makes with Germany that mirror our present are thematically chilling. Xillah reminds Zillah that the Weimar Republic had a constitution like the U.S. but their constitution didn’t save them against Hitler who abolished it. With the constitution gone, Hitler and his underlings and judiciary created laws to further Hitler’s occult mythic vision (the Master Race). And with his own race laws, he legalized the genocide of millions. Of course, Kushner highlights the turning point when death and destruction could have been prevented during the events of 1932-33. But those who saw, like Agnes and her friends, chose to do nothing. Eventually, like the frog slow boiled in the pot, the only thing they can do is escape. If they, as Agnes did, stay, they will be killed or swallowed up like Paulinka to join Hitler’s Third Reich “support group” of murderous maniacal, psychotic, evil accomplices. A different type of death, certainly more horrific and self-recriminating.

Mark Margolis in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Xillah muses about changing the play and warns Zillah that Agnes can’t hear her: she is dead as the past is dead. Zillah continues to beg Xillah. The dialogue that Kushner has written between them is humorous and reminiscent of the “Theater of the Absurd” genre and Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, where the playwrights tweak dramatic conventions. This is done to expand audience consciousness. Such creative license demands being available to “thinking outside of the box.” It also leads to the audience having to follow a play’s absurdities which can be as confounding as the illogical, dire thrusts of fascism, Reaganism, Trumpism.

Linda Emond in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

The absurdist feeling becomes that one has been caught up watching oneself as a part of the larger picture which one deludes themselves into believing they can control. In fact the “author” of our lives is not one we’ve necessarily chosen or know. At least Zillah knows her progenitor and argues with him and finally convinces Xillah to lift space/time constraints so that Agnes hears and speaks to her.

This section gives rise to a number of themes in this work that is dense with brilliance. Before Zillah connects with Agnes, we note that Agnes’s spirit atrophies and dies because her fear incapacitates her. Even if Zillah could break through the time barrier and move from the 1980s to 1933, Agnes’s routine of embracing fear and inaction has warped and destroyed any life in her. Life is movement, action, vitality. Doing something, anything (even escaping) would be better than just withering away. The irony of the play is the melding of the frame play into the Berlin story by Kushner/Xillah. He finally allows Zillah to warn Agnes to leave because she is doomed. Though it is not mentioned, we understand that those who did leave Germany early on did manage to save themselves while millions were swept up in genocide and Hitler’s war machine.

(L to R): Michael Urie, Michael Esper in ‘A Bright Room Called Day,’ by Tony Kushner,directed by Oskar Eustis at The Public (Joan Marcus)

Agnes’ reply to Zillah is not what we expect. It is mind-numbing, a warning to Zillah and us about our own time. It has the effect of a final incredible bomb blast that whimpers and fades. The full-on irony is as Agnes exhorts her/us, we hear, but it doesn’t register, it doesn’t matter. Thematically, Kushner suggests that we are plagued by the same inabilities, insufficiencies and cowardice that Husz ranted about in an earlier magnificent scene. Time inevitably doesn’t matter as we are like Agnes. Paralyzed, immobilized by discussion doing little to save ourselves. We must act! But how? To do what? And so it goes.

Kushner’s play should be revisted and it is a credit to The Public and Oskar Eustis for bringing it back in this unsettling, frustrating iteration. The parallels with each time period, whether we deign to acknowledge them or not, are striking. The threads which indict us about our alienation and powerlessness are spectres which should prick us to the marrow of our bones.