Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

‘A Doll’s House,’ Jessica Chastain’s Nora is Brilliantly Unbound

As a masterpiece of modern theater Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House presciently foreshadowed the diminution of a women’s role as homemaker. Ibsen shattered the notion of a woman being a husband’s pet, an obedient robot/doll with no autonomy or identity of her own, who cheerfully accepts the delimitation of traditional folkways. A maverick play at the time, A Doll’s House was considered controversial. Ibsen was forced to rewrite the ending for German audiences so it was acceptable.

What would those audiences have said about Amy Herzog and Jamie Lloyd’s stark, minimalist, conceptually powerful, metaphoric version currently at the Hudson Theatre? It is a version which relies on no distracting accoutrements of theatrical spectacle, i.e. period costumes and plush drapery. Nothing physically tangible assists with the unlacing of “the bodice” of Nora’s interior. With “little more” than cerebral irony, and emotional grist, Nora displays her soul in a genius enactment by the inimitable Jessica Chastain, in the production of A Doll’s House, which runs a spare one hour and forty-five minutes with no intermission.

The plot development, characters and themes are Ibsen’s. Nora, a pampered, babied housewife, to save her husband’s life, unwittingly commits fraud by borrowing money from loan shark Krogstad (Okieriete Onaodowan who in the first scene needed to project his voice so as not to appear a weak character which Krogstad is not). Complications arise when Torvald (an exceptional Arian Moayed), receives a bank promotion. With the additional money, Nora plans to quickly pay back Krogstad. But the loan shark threatens to expose Nora’s secret, unless she can save his job at the bank, where her husband has just become his boss.

Tensions increase when Torvald fires Krogstad and hires Nora’s friend Kristine (Jesmille Darbouze). Nora must confront the situation with Torvald before Krogstad exposes her and destroys Torvald’s reputation and their marriage.

Lloyd and Herzog are a fine meld. Herzog strips extraneous words and phrases, though not the substance of the pared-down dialogue. Her version is striking with a natural, informal, un-stilted speech for concentrated listening. There’s even a “fuck you” which Nora proclaims cheerfully to be bold, though not in Torvald’s hearing. The meat is Ibsen; the forks and knives to devour it are sleek and without ornamentation to distract. The themes and characterizations are bone chillingly articulate, which Herzog and Lloyd excavate with every word and phrase in this acute, breathtaking, ethereal, new version of A Doll’s House.

Lloyd eliminates the comforting, elaborate staging where actors might have moved to and fro amongst luxurious furniture and eye-catching, gloriously-hued dramatic sets that show Torvald’s preferred, lifestyle, which Nora scrimps from her own “allowance” to maintain. Instead, the ensemble’s movements are restrained. They step quietly around Soutra Gilmour’s set. Gilmour has distilled Lloyd’s vision to the back stage wall, top-half painted black, with attendant muted white painted on the bottom half of the wall. The flooring is grey. Predominant are the revolving platform and institutional-looking bland chairs which actors bring in and place on the sometime circling platform, or on its outer edges which don’t revolve.

Chastain appears twenty minutes before the production begins, seated in a chair revolving on the platform (I should have counted the repetitions, but I didn’t.). Sitting, she fascinates. Initially, to me, she was invisible; I was distracted, while she quietly walked on bringing her chair. She was a part of the onstage background, muted, unremarkable. That is perhaps one of the many concepts Lloyd and Herzog suggest with this enlightened version that is memorable because it is metaphysical and conceptual, giving rise to themes about soul interiors and women’s invisibility in the patriarchal culture.

One theme this set design suggests is that we travel in our own orbits, going in circles in our own perspectives, unseen and never truly known as psychically present, spiritual beings. And as Ibsen suggests, it takes an inner cataclysm such as Nora experiences to break from traditional mores and behavioral repetitions into a different consciousness and new way of being. This breakthrough, Nora attempts at the conclusion.

Amy Herzog’s modernized language version of A Doll’s House is one for the ages in focusing Ibsen’s power of developing characterizations. It presents an opportunity for Lloyd’s preferred, stylized, avant-garde staging, similar to what he used in Betrayal (2019) and Cyrano (2022). It requires the audience to listen acutely to every word of the dialogue and scrutinize the actors splendid, nuanced emotions which flicker across their faces. This is especially so of Chastain’s Nora, who is chained and bound symbolically throughout, minimally using gestures or any physicality, as she sits in a chair facing the audience. Predominately. she employs her voice and face to convey the interior-organ manifestation of Nora’s tortured, miserable psyche. For example when the wedding ring is returned, Nora and Torvald do not move; there is no ring. They look at one another, however, the unspoken meaning resonates loudly.

Even the tarantella Nora dances at the costume party, Chastain wrenches from herself sitting in the chair in a frantic nearly psychotic frenzy of shaking and kicking. The earthquake physicality that splits Chastain’s Nora apart is the only broad, physical movement, other than walking out of her stifling, meaningless existence, that Chastain and Lloyd effect with novel irony at the conclusion. The chair-dance is an explosive, rage-filled fit of exasperation, principally done for the purpose of distracting Torvald. Desperate to prevent his discovery of corrupt loan shark Krogstad’s blackmail plot, Nora’s diversion succeeds for a time. However, her fear and inner bleeding wounds only augment, until her behavior is exposed and Torvald unleashes his fury, vowing she must not infect the children with her poisonous corruption. Interestingly, the children ethereally “appear” as voices in voice- over recordings. Nora speaks to them, looking out in the direction of the audience. Hypocritically, Torvald demands she stay away from the children, though she must remain with the family to keep up appearances as his jeweled asset and prize doll.

With Lloyd’s symbolic staging, Chastain’s Nora proves that body, soul and mind are inseparably engulfed in the trauma of a paternalistic culture, represented by males who “love her the most” (her father and husband), and psychically straight-jacket and gaslight her to adopt their thoughts, behaviors and attitudes as right and true. To do this she nullifies her existence as a “human being.” In this production, Herzog, Lloyd, Chastain and the ensemble display this truth. It is undeniably representative of women in 1879, the projected number on the back wall of the stage that appears in the beginning of the production.

And when the number disappears, we understand that Soutra Gilmour’s black, white, grey set design, and Gilmour and Enver Chakartash’s costume design (modern dress black), function to speed us through 140 + representative years to display the dominant patriarchal attitudes today. These folkways still straight-jacket, demean and traumatize. If one thinks this is fatuous “woke” hyperbole that is finished, one has only to read the one in four statistics of women who are bound in violent relationships with male partners who beat or abuse them, yet cannot leave for fear of being alone or without the means to support themselves or their children. The LGBTQ community is not excepted from this. Humanity has a penchant for violence. If it is not externalized, the violence is psychic and emotional, where not a hand is raised toward a partner, yet the words and silences traumatize. It is the latter psychic trauma that Ibsen/Lloyd explore.

Whether in Ibsen’s historically, visually laden production of A Doll’s House, or in Lloyd’s naked, bleak and blasted version, it is a despotic spirit that demands obeisance, excluding other ways of being to exalt itself by oppressing and choking the life force from “the other,” whether gender-conforming or LGBTQ. That Chastain has the chops to convince us that we are witnessing every stressed fiber of her nerve endings annihilated, as she inhabits one of the most well-crafted characters in drama, is astounding and not to be underestimated, as some have done, implying her Nora “cries too much.”

Suffice to say, those are not female critics, of which there are far too few. However, her performance is emotionally handicapped accessible for those without a hearing ear, who may need to see Jamie Lloyd’s phenomenally sensitive direction a few times to “get it.” And happily many men do get it. They stood, cheered and whooped during the curtain calls when I looked around to see who was standing at Wednesday’s March 14th matinee. More importantly, women also cheered and whooped.

Clearly, husbands/partners, who might be like Torvald, need to see this production, if they suspect they are like him. Chastain’s Nora is an educational experience in how a particular woman suffers to the breaking point in order to be the prototype ideal wife and mother for a man’s “love” and acceptance. When Nora finally realizes she has the tools to free herself from the false and illusory prison of her own making, she throws off a life and role she believed made her happy to search for definitions of her own happiness.

Moayed’s Torvald, who portrays the solipsistic, presumptuous, self-aggrandizing, martinet with likable charm (how he does this is incredible), exposes her to herself. He smashes her fantasies that he is a white knight, who will do the “beautiful thing,” by sacrificing himself for her, as she has done for him.

Unfortunately, the only one who would sacrifice himself for her is on his way out of life. Chastain’s scenes with Michael Patrick Thornton’s Dr. Rank, who is the couple’s terminally ill close friend, are touching, warm and human, unlike her scenes with Torvald. They should be together, but she won’t push their light flirtations beyond, loyal to her fantasy of Torvald, until she isn’t.

Interactions between Nora and Torvald are increasingly transparent as they devolve into Torvald’s eventual explosion and hatred directed at Nora after discovering the truth. The scenes between Krogstad and Kristine pointedly contrast and move in the opposite direction. Kristine’s persuasive love of Onaodowan’s Krogstad makes him swallow his “pride” and give up his extortion plan. Truth is at the core of their love. Onaodowan and Darbouze are particularly strong and authentic in their scene together which reveals Kristine and Krogstad’s love has remained over the years. On the other hand Torvald and Nora’s toxic relationship functions in falsehoods. Lies are at its core, and what is presumed to be love is convenience and objectification. Torvald demands Nora be his dream doll and she obeys, though it demoralizes her soul.

Kristine’s troubled life has brought her to an understanding of herself in an honesty which Krogstad appreciates, for he wants to give up his corrupt way of life. That Lloyd has selected two Black actors to portray these characters reveals an underlying authenticity and exaltation for their love. Krogstad, who is in the shadows when we first meet him, as he sits behind Nora and blackmails her (unfortunately I had to read the script to understand these lines), appears the villain. He is made more villainous by the society’s ill treatment of him, but his love for Kristine redeems him. Torvald’s inability to love Nora damns them both.

Ironically, when her friend’s love is rekindled, Nora’s love ends, as she realizes Torvald’s true nature and relationship to her. Though he apologizes for “going off” in a diatribe superbly delivered by Moayed, Torvald’s narcissism which can’t abide anything hurting the Torvald “brand,” is egregious. His presumption is a delusion, for she saved his life; he wouldn’t exist but for her.

Herzog’s spare dialogue reveals how loathsome Torvald is in the last scene, when Nora tells him she believed him to be her white knight who would take the blame for her mistake. She insists she would have killed herself to stop his sacrifice for her. It is laughable when he says he would do anything for her, but he “won’t do that.” With conviction speaking for the entire tribe, Moayed states, “No man sacrifices his dignity for the person he loves.” Nora counters, “Hundreds of thousands of women have done that.” When Torvald begs her to stay for the children, he is the weak, despicable coward. His concern is pretentious show to make her feel guilty for leaving. Nora can’t be pressured. She knows Torvald will dump the inconsequential children’s care on their Nanny Anne-Marie (Tasha Lawrence).

Nora allows Torvald’s toxic masculinity to forge the chains which she uses to bind herself in the confines of a paternalistic culture that promotes attitudes about “the little wife.” Meanwhile, his little “bird” lacks a being and ethos apart from him. The only freedom, identity and empowerment Chastain’s Nora will ever receive is one she fashions for herself. This, she ironically and joyously enforces at the play’s conclusion.

How are such incredible performances by Chastain, Moayed and the others so beautifully shepherded? Lloyd economizes to the essence of thought in the lines reworked by Herzog. The evocative minimalism heightens the play’s timelessness and draws into crystal clarity the subtle, “loving” oppressive fantasies men and women (or whatever gender relationships), rely on to sustain power dynamics in their coupling. Without underlying truth and honesty to bolster the relationship and weather horrific storms, the illusions become insupportable and the personalities and relationships shatter.

Kudos to all in the creative team I may not have noted previously, including Jon Clark (lighting design), Ben & Max Ringham (sound design), the ominous, haunting music by Ryuichi Sakamoto & Alva Noto, and dance choreography by Jennifer Rias. For tickets to this maverick production, go to their website https://adollshousebroadway.com/

‘Crumbs From the Table of Joy’ Keen Company’s Revival of Lynn Nottage is a Must-See

From the excellent selection of music that fills the auditorium before Crumbs From the Table of Joy begins, to Ernestine Crump’s (Shanel Bailey) summation of the future after the roiling events with her family subsides, the Keen Company’s fine revival of Nottage’s play endears us. The playwright’s simplicity focuses on the hardships and relationship dynamics of a single father and two teenage daughters, migrating from the Jim Crow South to a Brooklyn recovering from the vagaries of WW II. Directed by Colette Robert, the heartfelt, lyrical production runs with one intermission at Theatre Row until April 1. It is a must-see for its superb performances and incisive, sensitive and coherent direction.

Ernestine is our guide through the year-long experiences negotiating her mom’s death and the family trials without their beloved mother to seamlessly make their lives easier. Their mom is intensely missed by all, especially Godfrey Crump (Jason Bowen) who yearns for companionship and tries to suppress his grief by joining up with Father Divine’s Peace Mission fellowship. Ernestine’s poetic recollections of the grieving time and the year of transformation, reveal a witty, talented raconteur. Wise beyond her years, she makes the audience her confidante to reveal the frightening, unfamiliar city and “romantic Parisian apartment” which sister Ermina (Malika Samuel) calls ugly. Occasionally, she calls up in her imagination scenes as she’d like her life to be, which the actors show with humorous results. Then the unfortunate reality encroaches, and what she wishes dissolves to what is.

The family are fishes out of water in an alien environment that never seems welcoming. The Brooklyn schools put Ermina in a lower grade. The students ridicule their country braids and home made dresses sewn with love. Generally they are treated with disdain and indifference. Surrounded by Jewish neighbors who remain aloof in their whiteness, they dp become friendly with upstairs neighbors who ask them to be their Shabbos goys.

They envy the elderly Levys, who seem joyful and full of laughter as they listen to radio and watch their TV programs. On the other hand Godfrey denies Ernestine and Ermina any entertainments on Sundays. Godfrey is an adherent of Father Divine’s principles which require sobriety and living abstemiously with few pleasures except Father Divine’s holy word. Thus, Ernestine’s misery is acute. but she overcomes her upset through humor and irony. Nottage bonds us to her heroine because of her alertly sage descriptions and authenticity, which never devolves into self pity. To support her dad and sister whom she loves, she keeps her own counsel and studies hard to finish high school. A senior she becomes engrossed with making her graduation dress by hand, working her seamstress skills. Hers will be the celebration of the first family member to receive a diploma.

While Ernestine applies herself in school, Ermina, who is 15-years old, fights her way into the social set and eventually becomes interested in boys. To establish that she won’t take sass from anyone, Ermina has her first successful fight and brings home the spoils of war in her pockets: a handful of greasy relaxed hair and a piece of grey cashmere sweater.

For his part their dad weeps, works nights at his job at the bakery, and loyally follows Father Divine. He counts on the minister to help him heal from the agonizing loss of his wife. Ernestine tells us that Father Divine has so enamored Godfrey that to be closer to him, he moved them to New York where he mistakenly thinks Father Divine lives because of a return address on the newsletter he receives as a subscriber. Their dad believes Divine’s “wisdom” is from God and he adheres to Divine’s principles to live cleanly, without alcohol or dancing or drugs, and be as devoted as a monk with celibacy as a badge of honor. Ernestine quips that this behavior is embraced by Godfrey, who never went to church or tipped his hat to a lady before they moved to Brooklyn. As for the other behaviors she doesn’t mention, we assume he did them all before their mother died.

Their home life revolves around Father Divine as their father attempts to become more spiritual and understand as much as possible under Divine’s tutelage which he seeks as he writes letters to him asking God’s advice to traverse this rough time in a bigoted environment of white people. That it was worse in the South doesn’t quite register and Nottage doesn’t make it a point. What she does indicate is that Godfrey doesn’t note the differences. For her part Ernestine appreciates that she is able to sit between two white girls touching shoulders in a movie theater, where this is not possible in a Jim Crow South which we infer from her excitement and enthusiasm. Also, she and Ermina like their nice neighbors upstairs who give them quarters for turning on the lights and the TV which they sometimes get to watch. However, to Godfrey, “white people” are a universal stereotype to be avoided and mumbled about.

Ironically, Ernestine points out his hypocrisy about selective criticism. He accepts Father Divine’s choice of a white wife to be another perfection of Godliness. Ernestine, who distrusts Father Divine, points out the difference between the God-like, elite Divine’s privilege to have a white wife, yet criticize white people to his Black followers. Meanwhile, her dad is just a poor Black man who sucks up a few crumbs from under the table of his life, which appears a drudgery especially with no woman at his side.

Enter Lily Ann Green (Sharina Martin) their mom’s deceased sister, who blows in unannounced, with values contrary to Father Divine/Godfrey and behaviors which upset Godfrey and put him on edge. Ernestine is thrilled she is there, even though Lily crashes with them, is completely self-absorbed and pushes her communistic beliefs wherever she goes,which is why she can’t hold a job. Interestingly, Nottage floats the two disparate philosophies which were to bring salvation to the Black society in America in the 1950s as sold and marketed by both: religion and the communist party.

Both preachers and communist leaders embraced the African American cause and, at their most egregious, exploited it for their own use. When Ernestine uses communist ideas in an essay that she hears Lily spout (this was during Senator Joe McCarthy’s Red Scare) her teacher is in an uproar. Likewise, Lily Ann ends up compromising Godfrey’s situation at work. Ernestine is forced to apologize as is Godfrey, who argues with Lily about not pushing communism vociferously to his daughters and others. He believes she is only making trouble. Though Lily Ann is interested in Godfrey and makes a play for him, he rejects her because he doesn’t agree with her politics and she dislikes Father Divine.

When the circumstances between them explode, Godfrey takes off a few from the family in frustration. During this respite, he meets Gerte Schulte (Natalia Payne) who emigrated from Germany after the war. Like Godfrey she is desperate for companionship and looking for someone to take care of her. Godfrey opens his heart and shares his circumstances. When he discusses Father Divine, she is receptive and together they seem to meld because of Gerte’s flexibility and charm. She is the antithesis of Lily Ann’s loose lifestyle, political determinism and stubbornness in having the upper hand with men.

Where Lily Ann is a catalyst and mentor for Ernestine and Ermina, Gerte becomes the catalyst to change their lives and split them apart. Nottage leaps her play’s action quickly forward when Godfrey brings Gerte home to introduce her to his daughters and Lily Ann. With her seductive, sweet charms, Gerte ingratiates herself into Godfrey’s life, moving herself from girlfriend to wife in a matter of a few days. The siblings are shocked as is Lily Ann. Godfrey expects all of them to live together and accept Gerte as his new wife. The results are not only humorous, they are necessary for Ernestine’s and Godfrey’s growth, as well as Lily Ann’s movement away from the dream of settling down with her sister’s husband.

As Ernestine Crump, Shanel Bailey is a phenomenon. Her narration is on-point, sensitive, nuanced and heartbreaking, especially at the end when she discusses what happens to each of the family members. Mindful of the narrative’s lovely poetic phrases, Bailey travels forward in character portraying Ernestine’s feelings in active dialogue with her dad, Lily Ann and Gerte, then seamlessly transfers to narrating her ironic perspective of them with grace. Bailey is winning and the production which hinges on her broad acting talents is strengthened with her brilliance of authenticity.

Though all of the ensemble shines, held together through Robert’s fine direction, another standout is Natalia Payne’s Gerte. Her accent is near perfect as a a German swanning through English. Payne makes Gerte likeable in her color blindness and utter humanity, as she forges a path for herself after the war. Though Nottage doesn’t fill in much of her backstory, we see she is a charming operator with resilience and an ability to read and understand situations, a survivalist. She and Godfrey end up with each other as a mutual benefit and by the end of the play, they move toward the intimacy and companionship they seek and need.

Malika Samuel’s Ermina is a breath of joyful fresh air. Her role is an addendum. It is a shame that she doesn’t have more dialogue for her funny, bright personality is winsome and the relationship Samuel and Bailey effect together rings with authenticity.

Nottage’s mouthpiece for her ideas, Lily Ann, is the most difficult of the characters to like because underneath her rhetoric, she is the most evasive. Though we attempt to infer the subtext of her character, Nottage doesn’t give us much to go on past what she stands for and says she believes in. However, her actions speak louder than her words and when Ernestine attempts to find the Harlem location of the communist party, the address that Lily Ann gives her doesn’t ring true. As Lily Ann, Sharina Martin is tough, manipulative, seductive and open-hearted with the sisters. She also layers Lily Ann’s personality so that we are wary that she is fronting and not delivering the truth to the family as she should be.

Jason Bowen’s Godfrey is spot-on believable and inhabits the role of the father desperate for answers in a world whose corrupt values make no sense except to be an incalculable frustration. His faith in Father Divine is believable to the point where we want Divine to be real. If he is duping Godfrey, who is vulnerable and heartbroken, it is a bitter and enraging Black on Black exploitation, skirting criminality. Because we empathize with Bowen’s Godfrey, we want the best for him. As Ernestine does we question his weak desperation falling for Gerte and marrying her so quickly. However, both are so needy. In the last scene Ernestine notes that Godfrey’s celibacy ends when Gerte and he make up after fighting. Bowen and Natalia Payne convey a roller coaster of emotions in their last scene together.

Kudos to the Keen Company’s creative team who bring together Colette Robert’s vision of the other 1950s America and how to prosper in spite of it. Creatives include Brendan Gonzales Boston’s spare, functional period scenic design, Johanna Pan’s costume design, Anshuman Bhatia’s lighting design, Broken Chord’s sound design and Nikiya Mathis’ wig design.

Crumbs from the Table of Joy continues until April 1 at Theatre Row. For tickets go to their website: https://www.keencompany.org/crumbsfromthetableofjoy

‘Elyria,’ by Deepa Purohit, a Gujarati Diaspora in Ohio, Review

The gorgeously vibrant sarees and salwar kameez take center stage as the characters spin and move exotically to traditional garba music. This is a festival celebration by Gujarati diasporans and other Indians who have found their way to Elyria, Ohio by 1982, the setting of the the titular play by Deepa Purohit. Currently in its World Premere at the Atlantic Theater Company’s Off Broadway Linda Gross Theater until March 19th, Elyria is incisively directed by Awoye Timpo and runs with one intermission. .

At its most powerful, Elyria captures the cultural nuances and shifting values gradually shaping the diasporans as they migrate from Kenya to London to Elyria. Through stylization and minimal, almost expressionistic set design, the play’s central tenet, how the past shakes itself into the present, unfolds in the imaginations of the characters, as they visualize their past interactions in flashbacks, which inform and drive their present behaviors.

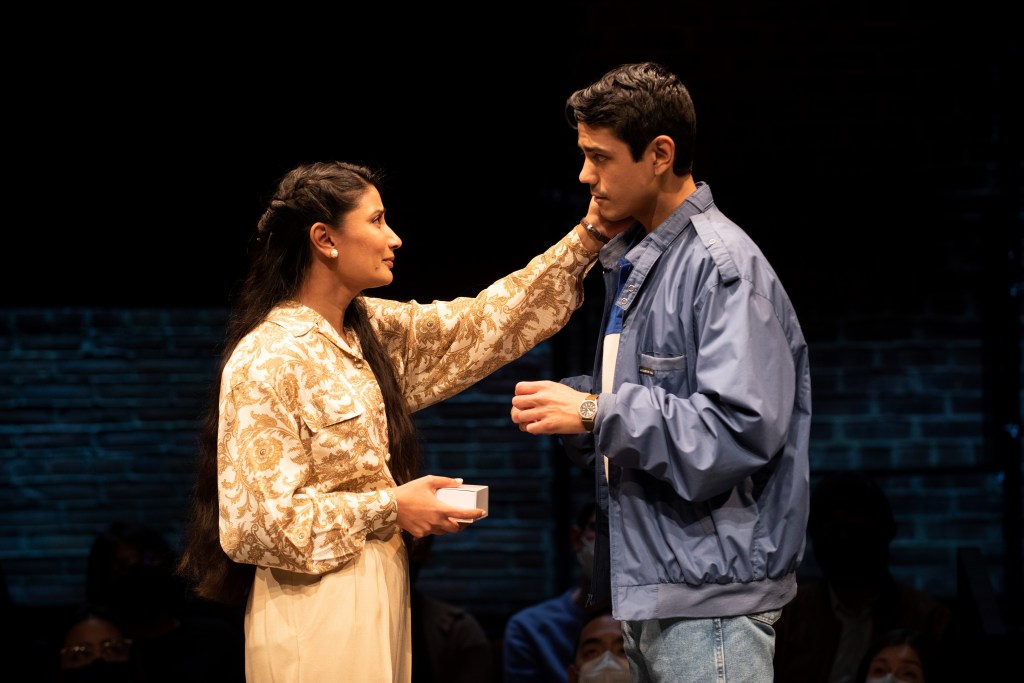

Elyria never descends completely into a melodrama of a threesome gone awry. This is because of the director’s elusive suggestion of the principals’ younger versions of themselves, portrayed by Mahima Saigal, Avanthika Srinivasan and Sanskar Agarwal, in flashbacks symbolically staged with accompanying music. The wistful compositions by Neel Murgai convey timber and moment. They are especially effective in the first act and in the flashbacks. For it is the nuance and surrealism of the past which lift Elyria beyond the mundane. As a result the evocative scenes present a dream-state atmosphere, like a series of meditations through which we intuit that Dhatta (Gulshan Mia) and Vasanta (Nilanjana Bose) make peace with themselves and each other by the play’s end.

Into the celebration of dance and happy festivities, Vasanta emerges on the dance floor to confront Dhatta and briefly move with her as they share awkward, stilted greetings. We anticipate from their encounter that they have known each other in another time and place, as it turns out when they were growing up together in Kenya. Though the contrast between the two women is not apparent initially, after they have additional encounters, we learn that Dhatta comes from an upper class strata of Gujarati society and Vasanta comes from a family with little means. As the play gradually unfolds, we learn that traditional cultural folkways bleed into the relationships and interactions of the characters, defining their social positions, identities and behaviors.

Without slamming rhetorical intrusions into the love triangle which developed elsewhere and ended after Dhatta married Charu (Bhavesh Patel) the playwright gradually reveals the surreptitious bonds among the characters, using Vasanta as the catalyst. Though she promised she wouldn’t, Vasanta follows Dhatta and Charu all the way to Elyria to confront them about Rohan (Mohit Gautam) who is the child of Vasanta and Charu’s love relationship. Dhatta has told Rohan that she is not his birth mother, but she is his mother forever. Rohan tells his college friend Hassanali (Omar Shafiuzzaman) that he plans to locate his birth parents after he and Hassanali graduate from college. Hassanali, a self-proclaimed computer genius, promises that he will help Rohan locate them on the “Interweb.”

Two ironies immediately present themselves. Rohan and Hassanali will be searching globally on the nascent and clunky forerunner of the internet whose communication protocols were not yet standardized (the internet was born in 1983). Ironically, Rohan’s birth parents are in his backyard and he could know them if someone would just “spill the beans.” However, revealing the secret is a monumental endeavor for the one carrying it, a happening more far flung then landing a spaceship on Neptune.

But even mountains move and an upset Vasanta finds the means financially with her hairdresser skills to make it to Elyria, supporting charming, con man husband Shiv (Sanjit De Silva) to proclaim her truth and see her grown-up child. Thus, the forward momentum of Purohit’s delicate unfolding plot complication unravels and destroys Dhatta’s world.

The secret is not revealed to Rohan during the play. Rohan believes that he was adopted by both Charu and Dhatta. It is his misfortune that he never receives the information that Charu is his real father with his mother’s childhood friend Vasanta as his birth mother. Dhatta is responsible for sharing the information that she promised Vasanta she would share. She doesn’t because she can’t; she is afraid. She knows that Charu loved Vasanta more, but until she begins to reconcile her past younger self with her older self’s experience, she can’t confront her husband about that love or the child it produced. The play is the revelation of the truth about Rohan and how it has impacted the characters and their love of themselves. Until they confront the truth, the guilt and self-loathing they’ve experienced keeping secrets from each other fester inside their souls and psyches.

At the heart of the complications, emotional problems and self-revulsion that each of the characters feel, are Indian cultural folkways. These (arranged marriages, economic status, paternalism) have oppressed both Vasanta and Dhatta and have damned Charu to a life of remote isolation from his son and his wife, as he perfunctorily performs his role as a father and husband. Indeed, Dhatta has devoted all of her love to Rohan and has unconsciously closed out Charu. He accuses her of foiling their marriage and giving all her attention to Rohan in a dynamic scene where Dhatta finally is able to tell him she knows about Vasanta. Admitting that she has raised up his son from a woman he still loves clears the air. On the other hand the truth heaps recriminations on Charu for clearly Dhatta is the better person, despite his accusations that accepting Rohan and raising him as her own son has negatively impacted their marriage.

Eventually, we discover their past and the traditions that bound them and still bind them making Charu culpable in what has happened. Years before Elyria and his marriage to Dhatta, Charu and Vasanta were lovers. However, their future marriage was doomed by her parent’s financial status and inability to pay the high dowry price required. Thus, Charu must marry someone financially well-off, in an economically viable arranged marriage of which his parents and Dhatta’s parents approve. Vasanta keeps secret her pregnancy and when Rohan is born, she delivers her son to Dhatta, keeping the baby with at least one birth parent, that is, if Dhatta agrees to the secrecy, which Vasanta eventually wants to be divulged to everyone.

Of course human beings don’t keep their promises, as we learn from the brief conversations between Bose’s Vasanta and Mia’s Dhatta. Dhatta never tells Charu she knows about his love for Vasanta. In the complication of generously swallowing dishonor and raising her husband’s former lover’s child, the secret lays dormant and calcifies her marriage and relationship with Charu. Interestingly, they aren’t able to have another child. To what extent this is because of the burden of secrets that Dhatta carries is unclear. However, when Vasanta’s stalks Dhatta and Charu to Elyria, she, too, breaks the promise that she would never pursue them or interfere in their marriage. Spending the time and money to hunt them down, then dragging along her unsuspecting, career failed husband Shiv to Elyria, we recognize how high the stakes are for her to reconcile with her son and former lover.

Both women must receive satisfaction; one to remain in darkness, the other to expose Rohan to the light. The result is devastaing and wonderful. The upheaval at the top of the play which sets in motion a dynamic that could have unfolded in a more forceful way is not the intent of Purohit’s subtle, delicate work, which meanders and flows until a final truth emerges on the brink of revelation. Who will be the first to bravely speak it out?

There are many themes in Elyria. One is an indictment of the mores whose strictures create problems for families, binding individual in fear. Charu is a traditional, conservative man who refuses to marry Vasanta though he loves her. He chooses to stay with his parent’s ways, hurting himself and all involved. Adhering to these folkways threatens to derail Rohan’s circumstances in the future because Charu wants Rohan to marry a woman of economic means, matching if not exceeding his own lifestyle as a surgeon. In one scene Charu attempts to steer Rohan toward beginning to get serious about meeting a girl he will marry. However, in his interactions with Hassanali, we discover Rohan is attracted to men. Unless the family is truthful and frees itself from such bondages, more trouble, pain and sorrow will follow them.

Kudos to Elyria‘s creative team which includes Parijat Desai (choreography) Jason Ardizzone-West (sets) Sarita Fellows (costumes) Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew (lighting) Amatus Karim-Ali (sound) Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew (projections) Nikiya Mathis (hair design) Neel Murgai (compositions). Praise to the ensemble, who are vibrant and on-point, and the director whose vision brings Purohit’s work to life and endears us to her characters’ movement toward reconciliation.

For tickets go to the Atlantic Theater Company website https://atlantictheater.org/

‘The Seagull/Woodstock, NY’ Review

The Seagull by Anton Chekhov is a favorite that receives productions and has been made into films, an opera and ballet performed all over the world. Some productions (with Ian McKellen at BAM in 2007) have been absolutely brilliant. What’s not to love about Chekhov with his dynamic and ironic character interactions, sardonic humor, enthralling conflicts that unspool gradually, then conclude with an ending that explodes and carries with it devastation and heartbreak. These elements cemented in Chekhov’s work since its initial production in 1896 represent what Chekhov himself described as a comedy.

Thomas Bradshaw, an obvious lover of Chekov’s The Seagull, has updated and adapted Chekhov’s work in the world premiere The Seagull/Woodstock, NY presented by The New Group. The playwright, who has previously worked with director Scott Elliott (Intimacy, Burning) has configured the characterizations, entertainment industry tropes, humor and setting in the hope of capturing Chekhov’s timelessness to more acutely evoke our time with trenchant dark ironies that are laughable. As he slants the humor and pops up the sexuality, which Chekhov largely kept on a subterranean level, Bradshaw has added another dimension to view the themes of one of Chekhov’s finest plays. Directed by Scott Elliott with a cast that boasts Parker Posey, Hari Nef, David Cale, Nat Wolff, Aleyse Shannon and Ato Essandoh as the principal cast, The Seagull/Woodstock, NY, at the Pershing Square Signature Theater has been extended to April 9th.

The play’s action takes place in a bucolic area in the Hudson Valley. Woodstock is the convenient “home away from home” of celebrities who live, work and fly between Los Angeles and Manhattan, and who feel they need to take a break between jobs, or just take a break from the stress of performance and helter skelter pressures and BS of the industry. The house where they retreat to is peopled by the family, caretakers, guests and a neighbor. The individuals are based on Chekhov’s characters, brother Soron, sister, actress Arkadina and son Constantine, who Bradshaw has renamed Samuel (David Cale) Irene (Parker Posey) and Kevin (Nat Wolff). Chekhov’s Trigoren, Arkadina’s lover, Bradshaw renames William, who is portrayed by Ato Essandoh. Nina, whose Chekhov name Bradshaw keeps is portrayed by Aleyse Shannon. Chekhov’s Masha becomes Bradshaw’s Sasha (Hari Nef).

In his update Bradshaw streamlines some of Chekhov’s dialogue and upturns the emphasis of conversation into the trivial without Chekhov’s character elucidation, as he spins these individuals into his own vision. The cuts truncate the depth of the characters, making them more shallow without resonance or humanity with which we might identify on a deeper level. However, that is Bradshaw’s point in relaying who they are and how they are a product of the noxious culture and the times we live in, unable to escape or rectify their being.

For example the initial opening conversation between Samuel (David Cale) and Kevin (Nat Wolff) loses the feeling of the protective bond between uncle and nephew scored with nuance and fine notes in Chekhov’s Seagull. Additionally, in their discussion of actress Irene, Kevin’s criticism of his mother emphasizes her faults and superficiality. In the Chekhovian version, the son expresses his feelings of inferiority in the company of the artists at his mother’s gatherings. Because of the son’s admissions we immediately understand his inner weakness and hopelessness, feelings which set up the rationale for his devastation of Nina’s abandonment and his suicide attempts later in the play.

Chekhov’s characterization of the actress and mother is tremendously subtle and cleverly humorous. Bradshaw’s iteration of the celebrity actress, her lover, the ingenue Nina and Irene’s brother become lost in the eager translation into comedy without the emotional grist and grief which fuels the humorous ironies of human frailty. Again, as we watch Bradshaw’s points about these individuals which reflect our modern selves, we laugh not with them ruefully, but at them for their obnoxiousness and blind hypocrisy.

Such points appear to be inconsequential and minor, however, the overall impact of Bradshaw’s characterizations makes them appear to be stereotypes of artificiality rather than individuals who are believably sensitive, vulnerable and hypocritical so that we care about them, yet find humor in their bleakness. Irene adds up to a figure of sometime cartoonish arrogance and pomposity without the sagacity and nobility of Chekhov’s Arkadina, who nevertheless is intentionally “oblivious” to herself out of desperation, hiding behind her facade, which on another level reveals a tragic individual. The same may be said for the characters of William and Nina who deliver the forward momentum of the work in their relationship that symbolically and sexually culminates in a bathtub on the stage where Nina previously masturbated as a key element of Kevin’s play. Their characters remain artificial and shallow, and the play’s conclusion and Nina’s collapse follows flatly without the drama and moment so ironically spun out in Chekhov’s Seagull.

Indeed, the meaning of Bradshaw’s work is clear. There has been a diminution of artistic greatness and sensibility, moment and nobility in our cultural ethos, which makes these players as inconsequential and LOL as he has drawn them. They are caricatures who wallow in artificiality and purposelessness, not of their own making. They have been caught up in the tide of the times and the vapid culture they seek to be celebrated in. That some of the actors push for laughs which don’t appear to come from organic, moment-to-moment portrayals makes complete sense. Theirs is a high-wire act and anything is up for grabs. Whatever laughter can be teased out, must be attempted. That is who these people are in The Seagull/Woodstock, NY.

Though the actors (especially Posey who portrays Irene with the similitude of other pompous, self-satisfied characters we’ve come to associate her with) attempt to get past the linearity of Bradshaw’s update, they sometimes become stuck, hampered by the staging, the playing area and direction whose action perhaps might have alternated between stage left and stage right (the audience is on three sides). Most of the action and conversation (facing the upstage curtain where Kevin puts on his play in the first act) takes place stage right. Since the set is minimalist and stylized with rugs, chairs and other props forming the indoor and outdoor spaces, the stage design might have been more fluid so that the various conversations were centralized. Unfortunately, some of the dialogue became swallowed up and the actors didn’t project to accommodate for the staging.

Only Nat Wolff’s portrayal of Kevin rang the most real and authentic. However, this is in keeping with the overall conceit that the playwright and director are conveying. Wolff doesn’t push for laughs and his portrayal of Kevin’s intentions are spot on. As a contrast with the other characters, he is a standout and again, this appears to be Bradshaw’s laden message. Kevin is driven to suicide by the situation, his mother, William’s remote selfishness and Nina’s devastation which she has brought upon herself. He is happier to be away from them. And perhaps Irene will be relieved, after all is said and done, that he has finally succeeded to end his misery. As Bradshaw has drawn her and as the director and Posey have characterized her, Irene has an incredible penchant for obliviousness.

At times the production is uneven and the tone is muddled. At its worst The Seagull/Woodstock, NY is a send up of Chekhov’s The Seagull that doesn’t quite make it. At its finest Bradshaw, Elliott and the ensemble reveal the times we live in are destroying us as we attempt to escape but can find no release nor sanctuary from out own artificiality and meaninglessness, as particularly evidenced in the characters of Irene, William and Nina. Only Kevin appears to have true intentions for his art but is stymied by the crassness of those considered to be exceptional but are mediocre. As in all great artistic achievement, only time is the arbiter of true genius. Perhaps Kevin’s time for recognition will come long after Nina, Irene and William are dead.

The creative team for The Seagull/Woodstock, NY includes Derek McLane (scenic design) Qween Jean (costume design) Cha See (lighting design) Rob Milburn & Michael Bodeen (sound design) UnkleDave’s Fight-House (fight and intimacy director). For tickets and times go to the website https://thenewgroup.org/production/the-seagull-woodstock-ny/

‘The Smuggler,’ A Thriller in Rhyme at Irish Repertory Theatre

In an energetic, boisterous performance delivered with a fever pitch that doesn’t quit or pause with quieter notes, Michael Mellamphy’s Tim Finnegan spills out The Smuggler, a story about how, as a naturalized citizen from Ireland, he was forced into a black-hearted situation he couldn’t refuse. In his delivery Mellamphy is like a high-speed train barreling down the track on a joy ride that threatens catastrophe at each turn in the journey, as customers and audience members alike are drawn in with his humor, excitement and storytelling verve, unfolding in rhyming couplets, that at times are insecure and slant. Written by Ronán Noone, himself an Irish-American immigrant from Galway, and directed by Conor Bagley, The Smuggler runs a slim 80 minutes at Irish Repertory Theatre in the W. Scott McLucas Studio Theatre. It has been extended until March 12.

At the heart of The Smuggler the protagonist (a con artist) attempts to get over with his charm and engagement to elicit audience sympathy. He seeks this as he tells about his plight to make a way for himself and his family in a culture that is the antithesis of welcoming and helpful to those “down on their luck.” When he’s fired from his job as a barman in Amity, Massachusetts, every door appears to shut in Finnegan’s face. Understanding the dark irony that America is portrayed as the land of “opportunity” in the alluring myth (the streets are paved with gold) told to strangers from other shores to entice them to leave their home country to provide cheap labor whether legal or illegal, he is caught in a morass of financial wrack and ruin of his own making.

Not only does Finnegan enjoy “a bit of drink” (an explanation for the selection of his job as barman) he appears not to be too swift in forward planning financially with his wife. Everything is a surprise that happens to them, not that they are responsible for selecting actions that leave them hanging off a cliff.

Many immigrants face hellish experiences, exploited by craven, greedy bosses, forced to live in overcrowded quarters, the pawns of merciless overlords wherever they turn. We have only to read about the history of America’s labor movement or Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers, or superlative, recent, non-fiction works (Tomato) to understand the desperation that immigrants go through, first to leave their countries, and then to attempt to “make it,” continuing the hell of the past in the present new “home.”

Thus, life moves from wheel to woe for those like Finnegan, who strike out to start a family, make missteps with bad choices, then fall on hard times. Finnegan and his wife live in a rental, that is no more than a shack with non-functioning plumbing. It is owned by a slumlord, a sleazy landlord who refuses to fix much of anything. As Finnegan unravels his dire circumstances with heavy poetic description, we identify with the immigrant experience, recognizing that the uniform abuse by those happy to mistreat and exploit the cheap labor of aliens and immigrants, is all too familiar.

What makes Finnegan’s experience a bit more interesting is how at each turn, being backed into a corner, by his boss, the landlord and the wife, he seeks a way to improve his family circumstances by “any” means necessary. Of course there’s the rub. “Any” reverts to lowering standards and morals he may have as a human being, as he turns to a life of theft and exploitation of other aliens and immigrants, he works with at his construction job.

Noone characterizes Finnegan during his monologue confessional with an emphasis on masculine bravado, fearlessness (especially when he confronts a menacing, “man-eating” rat) and chivalry in saving his wife and child from poverty, destitution and want. The heroic portrait is right out of “Captain America,” part of the glorious beauty of the American Dream of success, which lifts up the “heroic struggle” and vitiates the criminality, exploitation and violence that under-girds it. A good scam artist, Finnegan seductively blinds the audience to see things “his way,” so that they accept his justifications for his choices. His “bravery” and good will serves him like a magician’s prestidigitation at redirecting our understanding away from his conning nature.

Because his storytelling appears authentic and forthright, we gloss over his lack of accountability and responsibility in taking the low road toward crime, which he admits with (feigned?) abashment. Though he selects the exploitative way that harms and abuses others, we look at his efforts to succeed materially, not the dark side which he uses to get his “ill-gotten gains.” Finnegan’s “happy-go-lucky” attitude indicates that he knows the difference, but makes excuses for his behavior: “what else could he do?” The conclusion reinforces his triumph at “getting over.” The knock at the door, which we may anticipate brings recompense and punishment, never comes. Instead, the knock at the door brings a blessing. (There is no spoiler alert. You’ll just have to see The Smuggler to understand the symbolism of the knock on the door of the bar he was fired from, that his life of crime enabled him to buy back later on.)

Thus, Finnegan’s ultimate success as an Irish American is in how well he has gotten over, gotten the loot, made a beautiful material life for himself and his family, so they can “live happily ever after.” That there is some danger that lurks behind the triumphant Finnegan brand is smothered over by his intrepid nature and gumption to “just do it!” His is a male Cinderella story of achieving wealth. His macho actions to sacrifice for “the wife and family” actually reference the Trumps and Putins of the world and ridicule those who amass little monetarily, but scrape enough to get by, living in humility, honesty and decency. With boldness, his bravado encourages criminality and uplifts the fact that the law (represented by his adulterous cop brother-m-law) is capricious, unequally meted out and dysfunctional. Dali Lama, an unqualified loser, you have no place in America with your muted, unmaterialistic, nice-guy values

Rather than to evolve with hard work, sobriety, education and an ethos that undermines the exploitation of the abusive system that enslaves its workers and has converted Finnegan into a criminal, Finnegan jumps right in and embraces the “opportunity” to be at the top of the heap as “King Rat.” The symbolism of his killing the rat “guarding” a safe in the basement, whose contents he takes, is quite apparent. Ultimately, if justice ever knocks at Finnegan’s door, then he will have effected his own final self-destruction. Maybe! However, with his glib rhyming he proves to himself that there is nothing he can’t accomplish to become a success and be the type of “American” that extols scammers, con artists, schemers and material wealth, regardless of the soul damage and foulness created in the process. If he needs to, Finnegan has proven he’s a survivor. He can even get over in prison, if need be.

Clearly, Finnegan is smuggling more than a few ideas past the audience to justify his successful existence as proof of his greatness. The irony of themes and the well-written characterization acted by by Mellamphy and enhanced by the director’s vision is one more blow to smash the myths we may use to live by, as we dupe ourselves about America as a great nation. Clearly, it is fabulous for billionaires. For the immigrants who exploit and shred each other as the bosses divide and conquer them and us, it’s another America entirely. That Finnegan’s survival is cast in monetary terms aided and abetted to by his wife is his chief tragedy. But “what else can he do?” It’s the “land of the free and the home of the brave,” sung at every sports event nationwide.

Thanks to the creative team’s execution of set design which is just superb (Ann Beyersdorfer) atmospheric lighting design (Michael O’Connor) and sound design and original music (Liam Bellman-Sharpe). The production is first rate, if unsettling, as it leaves us with profound questions about how much we accept our foundational culture’s lies as truths.

For tickets to The Smuggler at Irish Repertory Theatre in the W. Scott McLucas Studio Theatre, go to their website https://irishrep.org/show/2022-2023-season/the-smuggler-2/

Ronán Noone

‘The Wanderers,’ Complex, Stylized, Engrossing Theater

Alternating seemingly disparate lives, two couples actually reveal a similar arc of development, from marriage to divorce in Ann Ziegler’s humorous, cleverly crafted The Wanderers, an exploration of how individuals create their own deceptions, live by them then shatter them, experiencing a fragmentation of self from which they never recover. Acutely directed by Barry Edelstein, and currently enjoying its New York City premiere at Laura Pels Theatre Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre, Ziegler’s play runs for 95 minutes with no intermission. Because of its popularity, it has been extended until 2nd April.

Anna Ziedler employs artifice of time and place to gradually promote the revelation of lives lived in quiet desperation and loss, unrealized until trigger moments of clarity occur. Ziegler’s play is ambitious. In it she presents complex, interwoven stories of culture clashes, identities in crises, and the search for happiness when its dream is an illusion created by self-deceptions. She accomplishes this storytelling of two interrelated couples allowing the audience to merge the pieces of the puzzle by the conclusion of this wonderful and gutsy play.

Ziegler introduces us to the central character Sophie (Sarah Cooper) who makes her announcement in present time, circa 2017, that she is divorcing her husband Abe (Eddie Kaye Thomas), whom she has known since she was a teenager. From this point on the play unfolds as a series of flashbacks of the two couples’ conversations. These occur in eight thematic scenes as pointed revelations in sequence, beginning with Abe’s parents Esther (Lucy Freyer) and Schmuli (Dave Klasko). Their conversations Ziegler carefully sculpts to contrast and abut Sophie’s and Abe’s interactions. To comprehend how the characters and their discussions are related, Ziegler keeps us focused on every word of dialogue, some of which is poetic and lovely. In other segments the dialogue is profound and richly thematic about identity, personal yearnings and self-revelation, especially in the scenes between Abe and Julia Cheever (Katie Holmes).

After Sophie introduces the profound metric of separation and divorce in her long marriage with Abe, Ziegler switches to another marriage which appears unrelated but is not. Esther and Schumuli (spoiler alert-Ziegler gradually reveals them to be Abe’s parents), are Hasidic Jews of the Satmar sect. When we meet them, their arranged marriage has just been performed. In a sweet, intimate repartee, they discuss how to begin the consummation of their union. Clearly, Schmuli is the naive one and Esther is forthright, adventurous and maverick, having read books on sex which Schmuli has not. The passive, accepting, dutiful wife Esther doesn’t appear to be in this brief interchange. It is Schmuli who is gentle, hesitant and sweetly anticipating something which he is clueless about.

With just a few defining details, the characterizations of Esther and Schmuli, incisively, sensitively portrayed by Freyer and Klasko, have been set by Ziegler. By the end of the threads of their interactions, which move for nine years through chronologically ordered vignettes that alternate in a revelatory puzzle with Sophie’s and Abe’s interactions, we discover just how rebellious Esther is. Not content with being a house frau with little of her own autonomy and authority to establish a career for herself, we learn that events push her to disavow her identify as a woman who must bow to the paternalistic culture fostered upon women of their sect. After she visits a friend in Albany (spoiler alert-her friend is Sophie’s mom), Esther learns that she can control her own body with birth control pills. After the momentous, life-changing birth of their son Abe, who Esther names “Abe” with great authority, contravening religious ritual, she tells Schmuli she wants no more children.

That Esther is forging out a life beyond the boundaries of their sect and her marriage only is strengthened when her father-in-law prevents her from seeing her daughters. He takes them to live in a household where she will not influence them against their religion. Schumli opposes her taking the pill and “slips” telling his father what Esther told him. It is a severe violation of the sect, whose intentions are to “increase and multiply.” Rather than to subject baby Abe to a life of religious bondage composed of ritual after ritual and still unable to see her daughters, Esther moves out of the neighborhood to raise her son Abe by herself. It is the equivalent of a divorce, though nothing occurs officially. Esther leaves convinced that the “grass is greener,” and she will live a much more fulfilled life out from under the paternalistic oppression of a religion and sect she disagrees with.

Esther and Schumuli’s crises points are revealed in Ziegler’s beautifully crafted dialogue. However, we don’t understand the final revelations and the profound impact of Esther and Schumuli’s crises on Abe and Sophie until the conclusion. That the play gyrates back and forth between the two couples, who mesmerize us to keep track of the details, is part of the enjoyment in solving the mystery which eventually crystallizes. And like the mysteries of lives explored, Ziegler throws in twists and curves, and with artifice, masks them over to create the surprises that happen.

Ziegler uses a conceit to manifest and uncover the hidden elements in the marriage of Sophie and Abe that dovetail with elements of Abe’s parent’s arranged marriage. In both marriages there are external and internal prison bars that keep the individuals from achieving happiness, fulfillment and peace individually and as couples. The conceit comes in the form of celebrity Julia Cheever (Katie Holmes), the character Ziegler uses to manifest the truths that both Sophie and Abe are avoiding in their marriage, their relationship with each other and with themselves.

Abe, who is a Pulitzer Prize winning novelist and success in his field, attends a reading where beautiful, luminous, entertainment star Julie Cheever is present. When Holmes’ Cheever replies to his email, they strike up an intimate and heartfelt conversation and Abe becomes so engrossed with writing to her, Sophie notices that he neglects his own children and their relationship.

Abe’s and Julia’s email conversations are acted out live by Eddie Kaye Thomas and Katie Holmes. Both actors are excellent and spot-on authentic. The emails are enlivened so that it is as if Julia Cheever is present with Abe, who is over the moon that someone of her celebrity, beauty and intelligence is complimenting him about his work, and inspiring him to discuss his parents and his upbringing. Indeed, Ziegler’s construct supplements Abe’s discussions with Sophie. What is revealed melds and substantiates the revelatory conversations of Esther and Schmuli, though these happened long before Abe was born. Because only Esther raised him, Abe never had an understanding of his father, nor the religion that would have given him power as a man. Raised outside of it without a father role model, he is lost. Though Esther encouraged his love of words and his wonderful success as a writer, as did Sophie, there are gaps in his soul, and his life’s vision is myopic.

As Julia’s and Abe’s online relationship strengthens, eventually Abe wishes to meet her. However, this is not to be. After his father dies, his discussions with Cheever eventually lead to a revelation that is devastating for both Abe and Sophie.

Ziegler’s thematically structured scenes featuring the couples, first appearing disparate, are eventually conjoined. However, unless you read the script, think about the play at length or see it a few times, it is easy to miss the importance of what is happening as a precursor to Schmuli’s death, or understand why Abe decides to re-write and fictionalize how his father died to make his death more beautiful and moving.

Zielgler’s play is fluid and slips in and out of present and past ,which appear to be concurrent, though they are not. The artifice evokes aspects of consciousness and spirituality that are opaque. Because of the conceit that Ziegler has chosen to use as a vehicle to uncover the mysterious elements of her characters and their lives, the scenes suggest linearity, but for the sake of mystery, they are profound and labyrinthine. Like all flashbacks, the scenes occur as a result of memory. Clearly, the characters nuance the events.

Well acted, the director has finely shepherded this as an ensemble piece, though only the married couples interact with each other. Yet, we feel we know them, know their agony and brilliance which surprise us in their final revelations.

Kudos to Marion Williams for the stylized spare set whose backdrop is populated by pages of books which encompass the great expanse of reading that the characters have accomplished in their lives. A table and some chairs are used to evoke a bedroom and other spaces. And of course there are piles of actual books, almost an anachronism in a digital age. Kudos to other creatives who completed the director’s vision for Ziegler’s play. These include David Israel Reynoso (costume design), Kenneth Posner (lighting design), Jane Shaw (original music & sound design), and Tommy Kurzman (hair and wig design).

The Wanderers is thought-provoking, symbolic and most strongly felt when the superb actors are authentic and in the moment, inhabiting the characters and making them alive. This play has proven itself a must-see by audience word of mouth, for it has garnered an extension. To purchase tickets go to their website.

https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2022-2023-season/the-wanderers/performances

‘Endgame’ by Samuel Beckett at Irish Repertory Theatre is Amazing

Nobel prize winner Samuel Beckett suffered years of rejection until his wife managed to sell his work which gradually put him on the map. Now we question how this rejection was possible because his work is timeless and exemplifies his genius. His particular greatness lies in his creation of spare, staccato, memorable dialogue, enigmatic characters and static situations as metaphors of human existence and its banal, opaque meaninglessness. How could anyone miss Beckett’s exceptionalism? In Endgame Beckett believed he was at his best. Gloriously, the Irish Repertory Theatre is presenting this work and the production directed by Ciarán O’Reilly reflects the accuracy of Beckett’s opinion.

Starring the irrepressible Bill Irwin as Clov and stolid John Douglas Thompson as Hamm, the production is perfection in its minimalism and ironies. It appropriately allows the audience to focus on the principal characters and their dire circumstances as they confront the end of the world, the end of their relationships with each other, their personal closure, and the abject null of lives lived in their last days, without joy, empathy or compassion. Interestingly, the play’s conclusion appears to happen in real time. When the final words are proclaimed, Hamm’s story is told and the lights go out to audience applause. All that has been said and has needed to be expressed is said and done. And there is the precise end of it, as the audience is left to wonder and take nothing for granted about their own existential happenstance and what they have just witnessed in this shared humanity that plays out in a tragicomic unspooling.

Apart from their physical conditions of wrack and ruin, the characters are essentially ciphers. Hamm is blind and wheelchair bound, dependent on Clov, his handicapped, scattered servant, who begrudgingly comes to his every “whistle” and obeys Hamm’s commands. Clearly, their symbiotic relationship is one based on mutual abuse and co-dependence, as there is no love lost between them, though they’ve known each other since Clov was a child. Throughout the play, Clov limps with a barely controllable gait and awkward mobility to Hamm’s imperious orders. Toward the end of their repetitious tedium together, Clov even remarks he doesn’t understand why he continues to obey the cantankerous, unloving, pain-filled, acerbic older man.

In addition to Clov and Hamm are Hamm’s elderly parents who abide in the same large, spare room. They, also have lost their mobility and live without their legs in garbage cans filled at the bottom, first with sawdust, then more recently with sand. There are lids on the garbage cans, and the parents pop up for a conversation, until Hamm is tired of them and tells Clov to shut them up and close them out. Ironically, in the brief time we come to know father Nagg (Joe Grifasi) and mother Nell (Patrice Johnson Chevannes), we appreciate their relationship and the affection between them. Beckett reveals their togetherness as they recall the good times they had with each other, even making light of the accident when they both lost their legs. They put up with their son’s abusive, cruel nature and forbear under his insults (he refers to Nagg as a “fornicator”). As a result we perceive them as empathetic characters, while Hamm appears all the more obnoxious and querulous.

These four hapless individuals are perhaps the last human beings in the world. Hamm refers to the external environment outside the ramshackle building where they reside to be filled with death. The assumption is that the apocalypse has happened and there’s nothing left but a wasteland. The only objects that appear to make sense are inside their meager abode. These include Hamm’s piercing whistle, a few biscuits (in the play they look like dog biscuits) and Clov’s paraphernalia which include a spyglass and a ladder, an alarm clock and a few other items. There is also Hamm’s pet dog which is a stuffed animal, which may or may not give him comfort amidst his whining about “it’s” being enough, asking for his pain killer and his attempts to finish the story that he’s trying to tell, which symbolizes his and Clov’s lives.

The laughable irony is that the end of days are inhabited by these infirm individuals led by a powerless, despotic miscreant who presides over the others like a king, though he is powerless, halt, lame and blind (the Biblical reference is intimated). Instead of his physical helplessness guiding him into humility, the opposite is apparent. He is full of himself in his miserable state, which he appears to masochistically enjoy. (“Can there be misery loftier than mine? No doubt.”)

Hamm and Clov are contrapuntal. They are unique personalities and they contradict each other but come to the same conclusions. Their state of existence must end and it has gone on long enough without meaning. As they speak to each other in short bursts of, oppositional banter, the overall effect is humorous, like a bad joke or punchline. However, their thrust and parry about “nothing” has philosophical power in their sporadic digressions about life, time and existence. Their interactions often end with a surprising, pithy statement from either of them and the overall effect is also like a poetic riff. For example Hamm says, “It’s a day like any other.” Clov counters, “As long as it lasts. All life long the same inanities.” In their counterpoint, there is the great observational moment about the redundant, vapid routines of living.

Considering that apart from a few moments when Clov looks out the window, and Hamm directs him to “drive” his wheelchair around in a circle, Clov kills a flea by throwing powder down his pants and Hamm uses a staff-like implement to try to move himself which he can’t, little happens. From beginning to ending they know the situation is absurd because their end is inevitable and irrevocable. And because they are helpless against time and existence itself, they can do nothing except what they do and say which is both funny and tragic.

Bill Irwin’s Clov is a mastery of awkward physicality precisely effected. He is imminently watchable and uncharacteristic in his movements which are surprising and antic. In his stasis, John Douglas Thompson is his frustrated counterpart. Their banter is humorous and paced with authenticity bringing on the chortles and laughter because their characters are so passive and truthful about their condition. No one is raging against the storm which has already happened. They are waiting the interminable wait for “the end.”

O’Reilly’s direction and staging align with Beckett’s intent and we find ourselves mesmerized and waiting for the shoe to drop,, which only does in the little details and actions. One example of this occurs when Clov sets up the ladder and climbs it, anchoring his leg so he might safely look out the window on the “grey.” Another example occurs when Clov gets rid of the flea with the white powder which he roughly sprinkles down his baggy pants. A third action occurs when Clov brings out an alarm clock and hangs it on the wall. Each of these “events” and others (Hamm’s petting his stuffed dog, Hamm’s attempting to move himself with the gaff) create a kind of suspense that ends in nothingness. This is one of the themes of Endgame; ultimately, our actions result in little that impacts or changes existence. However, they do help to pass the time and “entertain” us until “the end,” which is uncertain.

Charlie Corcoran’s scenic design, Orla Long’s costume design, Michael Gottlieb’s lighting design, M. Florian Staab’s original music and sound design convey the austere setting of a ramshackle room in a house beset by a post-apocalyptic, end times scenario. That the title references a game of chess where there are no winners and one of the players (Clov) threatens to leave numerous times but remains at “the end” is to Beckett’s purpose that all inevitably wanders into empty inaction which has little substance or meaning. Thus, we are left seeing characters confronting what they cannot, as we witness our own inability to reckon that there is an “end” to all of “this.” And as Nell states, nothing is funnier than unhappiness. So as we watch the characters struggle with their fateful endings, we laugh because life is nonsensical. And we are sad for the tragedy that reflects our own humanity.

This is an amazing production with flawless performances that you don’t want to miss. For tickets and times go to their website https://irishrep.org/show/2022-2023-season/endgame-2/