Blog Archives

‘Uncle Vanya,’ Steve Carell in a Superb Update of Timeless Chekhov

A favorite of Anton Chekhov fans is Uncle Vanya because it combines organic comedy and tragedy emerging from mundane, static situations, intricate, suppressed characters and their off-balanced, mired-down relationships. Playwright Heidi Schreck (What the Constitution Means to Me), has modernized Vanya enhancing the elements that make Chekhov’s immutable work relevant for us today. Lila Neugebauer’s direction stages Schreck’s Chekhov update with nuance and singularity to make for a stunning premiere of this classic at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont in a limited run until June 16th.

With a celebrated cast and beautifully shepherded ensemble by the director, we watch as the events unfold and move nowhere, except within the souls of each of the characters who climb mountains of elation, fury, depression and despair by the conclusion of this two act tragicomedy.

Schreck has threaded Chekhov’s genius characterizations with dialogue updates that are streamlined for clarity, yet allow for the ironies and sarcasm to penetrate. At the top of the play Steve Carell’s Vanya is hysterical as he expresses his emotional doldrums at the bottom of a whirlpool of chaos which has arrived in the form of his brother-in-law, Professor Alexander (the pompous, self-important Alfred Molina in a spot-on portrayal), and Alexander’s beautiful, self-absorbed, younger-by-decades wife Elena (Anika Noni Rose). Also present is the vibrant, ironic, self-deprecating, overworked Dr. Astrov (William Jackson Harper), a friend who visits often and owns a neighboring estate.

During the course of the first act, we are witness to the interior feelings and emotions of all the characters who in one way or another are bored, depressed, miserable and disgusted with themselves. Vanya is enraged that he has taken care of Alexander’s lifestyle, even after his sister died in deference to his mother, Maria (Jayne Houdyshell). He is particularly enraged that he believed with is mother that Alexander was a “brilliant” art critic who deserved to be feted, petted and over credited with praise when he lived in the city.

Having clunked past his prime as an old man, Alexander has been fired because no one wants to read his work. He and Elena have run out of money and are forced to stay in the family’s country estate with Vanya and Sonia, Alexander’s daughter (the poignant, heartfelt Alison PIll), away from the limelight which shines on Alexander no more. Seeing Alexander in this new belittlement, though he orders around everyone in the family, who must wait on him hand and foot, Vanya is humiliated with his own self-betrayal. He didn’t realize that Alexander was a blowhard who duped and enslaved him to labor on the farm to supporting his high life, while he pursued his “important” writing. Vanya and Sonia labor diligently to make sure the farm is able to support the family, though it has been a difficult task that recently Vanya has grown to regret. He questions why he wasted his years on a man unworthy of his time and effort, a fraud who knows little about art.

Likewise, Astrov questions his own position as a doctor, admitting to Marina (Mia Katigbak), that he feels responsible for not being able to help a young man killed in an accident. To round out the “les miserables,” Alexander is upset that he is an old man who is growing more decrepit by the minute as he endures believing his young, beautiful wife despises him. Despite his upset, Alexander expects to be waited on by his brother-in-law, mother-in-law and in short, everyone on the estate, which he has come to think is his, by virtue of his wanting it. Though the estate has been bequeathed to his daughter Sonia by Vanya’s sister, his first wife, Alexander and Elena find the quiet life in the country unbearable.

As they take up space and upturn the normal routine of the farm, Elena has been the rarefied creature who has disturbed the molecules of complacency in the lives of Vanya, Sonia and Astrov. Her beauty is shattering. Sonia hates her stepmother, and both Vanya and Astrov fall in love and lust with her. As a result, their former activities bore them; they cannot function with satisfaction, and have fallen distract with want, craving the impossible, Elena’s love. Alexander fears losing her, but realizes if he plays the victim and harps on his own weaknesses of old age, as distasteful as he is, Elena is moral enough to attend to him, though she is bored and loathes him in the process.

The situation is fraught with problems, hatreds, regrets, upsets and soul turmoil, which Schreck has stirred following Chekhov’s dynamic. Thus, Carell’s Vanya and Harper’s Astrov are humorous in their self-loathing as is the arrogant Alexander and vapid Elena who Sonia suggests can end her boredom by helping them on the farm. Of course, work is not something Elena does, which answers why she has married Alexander and both have been the parasites who have sucked the lifeblood of Vanya and Sonia, as they labor for their “betters,” who are actually inferior, ignoble and selfish.

To complicate the situation, Sonia is desperately in love with Astrov, who can only see Elena who is attracted to him. However, Elena is afraid to carry out the possibility of their affair. Instead, she destroys any notion that Sonia has of being with Astrov by ferreting out Astrov’s feelings for Sonia which tumble out as feelings for Elena and a forbidden, hypocritical kiss which Vanya sees and adds to his rage at Elena’s self-righteousness and martyred morality. When Elena tells Sonia that Astrov doesn’t love her, Sonia is heartbroken. It is Pill’s shining moment and everyone who has experienced unrequited love empathizes with her devastation.

When Alexander expresses his plans to sell the estate and take the proceeds to live in the city in a greater comfort and elegance, Carell’s Vanya excoriates Alexander and speaks truth to power. He finally clarifies his disgust for the craven and selfish Alexander, despite Maria’s belief that Alexander is a great man, not the fraud Vanya says he is.

It is a gonzo moment and Carell draws our empathy for Vanya who attempts to expiate his rage, not through understanding how he is responsible for being a dishrag to Alexander, but through manslaughter. The scene is brilliantly staged by Neugebauer and is both humorous and tragic. The denouement happens quickly afterward, as each of the characters turns to their own isolated troubles with no clear resolution of peace or reconciliation with each other.

The ensemble are terrific and the actors are able to tease out the authenticity of their characters so that each is distinct, identifiable and memorable. Naturally, Carell’s Vanya is sympathetic as is Pill’s heartsick Sonia, for they nobly uphold the ethic that work is a kind of redemption in itself, if dreams can never come true. We appreciate Harper’s Astrov in his love of growing forests and his understanding of the extent to which the forests that he plants will bring sustenance to the planet, if even to mitigate only somewhat the society’s encroaching destructiveness. Even Katigbak’s Marina and Sonia’s godfather Waffles (the excellent Jonathan Hadary), are admirable in their ironic stoicism and ability to attempt to lighten the load of the others and not complain.

Finally, as the foils Molina’s Alexander and Noni Rose’s Elena are unredeemable. It is fitting that they leave and perhaps will never return again. The chaos, misery, dislocation and confusion they leave in their wake (including the somewhat adoring fog of Houdyshell’s Maria), are swallowed up by the beautiful countryside and the passion to keep the estate functioning which Sonia and Vanya hope to achieve in peace. Vanya, for now, has thwarted Alexander, by terrorizing Alexander into obeying him in a language (threatening his life), he understands. For this we applaud Vanya.

When Alexander and Elena leave, the disruption has ended and they take their drama and chaos with them. It is as if they were never there. As Vanya and Sonia handle the estate’s paperwork, which they’ve neglected having to answer Alexander’s every need, the verities of truth, honor, nobility and sacrifice are uplifted while they work in silence, and peace is restored to the estate, though they must suffer in not achieving the desires of their lives.

Neugebauer and Schreck have collaborated to create a fine version of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya that will remain in our hearts because of the simplicity and clarity with which this update has been rendered. Thanks go to the creative team. Mimi Lien’s set design functions expansively to suggest the various rooms of the estate, the garden and hovering forest in the background. A decorative sliding divider which separates the house from the forest and allows us to look out onto the forest and woods beyond (a projection), symbolizes the division between the natural and the artificial worlds which influence and symbolize the characters and what they value.

Vanya and the immediate family take their comforts from the earth and nature as does Astrov. Alexander and Elena have forgotten it, finding no solace in the beautiful surroundings and quiet, rural lifestyle which they find boring because they prefer chaos and the frenetic atmosphere of society. Essentially they are soul damaged and need the distractions they’ve become used to when Alexander was famous and the life of the party before he got tiresome and old and disgusting in the eyes of Elena and those who fired him..

The projection of trees that expands entirely across the stage in the first act is a superb representation of what is immutable and must be preserved as Astrov works to preserve. The forest of trees which is the backdrop of the garden, sometimes sway in the wind. The rustling leaves foreshadow the thunder storm which throws rain into the garden/onstage. The storm symbolizes the storm brewing in Uncle Vanya about Alexander, and emotionally manifests when Alexander suggests they sell the estate to fulfill his personal agenda.

During the intermission every puddle and water droplet is sopped up by the tech crew. Kudos to Lap Chi Chu & Elizabeth Harper for their lighting design and Mikhail Fiksel & Beth Lake for their sound design which bring the symbolism and reality of the storm home.

The modern costumes by Kaye Voyce are character defining. Elena’s extremely tight knit, brightly colored, clingy dresses are eye candy for her admirers as she intends them to be to attract their attention, then pretend she doesn’t want it. Of course she is the leisurely swan while Sonia is the ugly duckling in work clothing, Grandmother Maria dresses like the “hippie radical feminist” that she is, and Marina is in a schmatta as the servant who cooks and cleans. Here, it is easy for Elena to shine; there is no competition.

Vanya looks frumpy and uncaring of himself. This reflects his depression and lack of confidence, while Molina’s Alexander is dressed in the heat like a peacock with a scarf, cane and hat and cream-colored suit when we first see him. Astrov is in his doctor’s uniform, utilitarian, purposeful, then changes to more relaxed clothing. The costumes are one more example of the perfection of Neugebauer’s vision and direction of her team.

Uncle Vanya is an incredible play and this update does Chekhov justice. It is a must-see for Schreck’s script clarity, the actors seamless interactions and the creative teamwork which elevates Chekhov’s view of humanity with hope, sorrow and love in his characterizations, especially of Vanya.

Uncle Vanya runs two hours twenty-five minutes including one intermission, Lincoln Center Theater at the Vivian Beaumont. https://www.lct.org/shows/uncle-vanya/whos-who/

‘The Seagull/Woodstock, NY’ Review

The Seagull by Anton Chekhov is a favorite that receives productions and has been made into films, an opera and ballet performed all over the world. Some productions (with Ian McKellen at BAM in 2007) have been absolutely brilliant. What’s not to love about Chekhov with his dynamic and ironic character interactions, sardonic humor, enthralling conflicts that unspool gradually, then conclude with an ending that explodes and carries with it devastation and heartbreak. These elements cemented in Chekhov’s work since its initial production in 1896 represent what Chekhov himself described as a comedy.

Thomas Bradshaw, an obvious lover of Chekov’s The Seagull, has updated and adapted Chekhov’s work in the world premiere The Seagull/Woodstock, NY presented by The New Group. The playwright, who has previously worked with director Scott Elliott (Intimacy, Burning) has configured the characterizations, entertainment industry tropes, humor and setting in the hope of capturing Chekhov’s timelessness to more acutely evoke our time with trenchant dark ironies that are laughable. As he slants the humor and pops up the sexuality, which Chekhov largely kept on a subterranean level, Bradshaw has added another dimension to view the themes of one of Chekhov’s finest plays. Directed by Scott Elliott with a cast that boasts Parker Posey, Hari Nef, David Cale, Nat Wolff, Aleyse Shannon and Ato Essandoh as the principal cast, The Seagull/Woodstock, NY, at the Pershing Square Signature Theater has been extended to April 9th.

The play’s action takes place in a bucolic area in the Hudson Valley. Woodstock is the convenient “home away from home” of celebrities who live, work and fly between Los Angeles and Manhattan, and who feel they need to take a break between jobs, or just take a break from the stress of performance and helter skelter pressures and BS of the industry. The house where they retreat to is peopled by the family, caretakers, guests and a neighbor. The individuals are based on Chekhov’s characters, brother Soron, sister, actress Arkadina and son Constantine, who Bradshaw has renamed Samuel (David Cale) Irene (Parker Posey) and Kevin (Nat Wolff). Chekhov’s Trigoren, Arkadina’s lover, Bradshaw renames William, who is portrayed by Ato Essandoh. Nina, whose Chekhov name Bradshaw keeps is portrayed by Aleyse Shannon. Chekhov’s Masha becomes Bradshaw’s Sasha (Hari Nef).

In his update Bradshaw streamlines some of Chekhov’s dialogue and upturns the emphasis of conversation into the trivial without Chekhov’s character elucidation, as he spins these individuals into his own vision. The cuts truncate the depth of the characters, making them more shallow without resonance or humanity with which we might identify on a deeper level. However, that is Bradshaw’s point in relaying who they are and how they are a product of the noxious culture and the times we live in, unable to escape or rectify their being.

For example the initial opening conversation between Samuel (David Cale) and Kevin (Nat Wolff) loses the feeling of the protective bond between uncle and nephew scored with nuance and fine notes in Chekhov’s Seagull. Additionally, in their discussion of actress Irene, Kevin’s criticism of his mother emphasizes her faults and superficiality. In the Chekhovian version, the son expresses his feelings of inferiority in the company of the artists at his mother’s gatherings. Because of the son’s admissions we immediately understand his inner weakness and hopelessness, feelings which set up the rationale for his devastation of Nina’s abandonment and his suicide attempts later in the play.

Chekhov’s characterization of the actress and mother is tremendously subtle and cleverly humorous. Bradshaw’s iteration of the celebrity actress, her lover, the ingenue Nina and Irene’s brother become lost in the eager translation into comedy without the emotional grist and grief which fuels the humorous ironies of human frailty. Again, as we watch Bradshaw’s points about these individuals which reflect our modern selves, we laugh not with them ruefully, but at them for their obnoxiousness and blind hypocrisy.

Such points appear to be inconsequential and minor, however, the overall impact of Bradshaw’s characterizations makes them appear to be stereotypes of artificiality rather than individuals who are believably sensitive, vulnerable and hypocritical so that we care about them, yet find humor in their bleakness. Irene adds up to a figure of sometime cartoonish arrogance and pomposity without the sagacity and nobility of Chekhov’s Arkadina, who nevertheless is intentionally “oblivious” to herself out of desperation, hiding behind her facade, which on another level reveals a tragic individual. The same may be said for the characters of William and Nina who deliver the forward momentum of the work in their relationship that symbolically and sexually culminates in a bathtub on the stage where Nina previously masturbated as a key element of Kevin’s play. Their characters remain artificial and shallow, and the play’s conclusion and Nina’s collapse follows flatly without the drama and moment so ironically spun out in Chekhov’s Seagull.

Indeed, the meaning of Bradshaw’s work is clear. There has been a diminution of artistic greatness and sensibility, moment and nobility in our cultural ethos, which makes these players as inconsequential and LOL as he has drawn them. They are caricatures who wallow in artificiality and purposelessness, not of their own making. They have been caught up in the tide of the times and the vapid culture they seek to be celebrated in. That some of the actors push for laughs which don’t appear to come from organic, moment-to-moment portrayals makes complete sense. Theirs is a high-wire act and anything is up for grabs. Whatever laughter can be teased out, must be attempted. That is who these people are in The Seagull/Woodstock, NY.

Though the actors (especially Posey who portrays Irene with the similitude of other pompous, self-satisfied characters we’ve come to associate her with) attempt to get past the linearity of Bradshaw’s update, they sometimes become stuck, hampered by the staging, the playing area and direction whose action perhaps might have alternated between stage left and stage right (the audience is on three sides). Most of the action and conversation (facing the upstage curtain where Kevin puts on his play in the first act) takes place stage right. Since the set is minimalist and stylized with rugs, chairs and other props forming the indoor and outdoor spaces, the stage design might have been more fluid so that the various conversations were centralized. Unfortunately, some of the dialogue became swallowed up and the actors didn’t project to accommodate for the staging.

Only Nat Wolff’s portrayal of Kevin rang the most real and authentic. However, this is in keeping with the overall conceit that the playwright and director are conveying. Wolff doesn’t push for laughs and his portrayal of Kevin’s intentions are spot on. As a contrast with the other characters, he is a standout and again, this appears to be Bradshaw’s laden message. Kevin is driven to suicide by the situation, his mother, William’s remote selfishness and Nina’s devastation which she has brought upon herself. He is happier to be away from them. And perhaps Irene will be relieved, after all is said and done, that he has finally succeeded to end his misery. As Bradshaw has drawn her and as the director and Posey have characterized her, Irene has an incredible penchant for obliviousness.

At times the production is uneven and the tone is muddled. At its worst The Seagull/Woodstock, NY is a send up of Chekhov’s The Seagull that doesn’t quite make it. At its finest Bradshaw, Elliott and the ensemble reveal the times we live in are destroying us as we attempt to escape but can find no release nor sanctuary from out own artificiality and meaninglessness, as particularly evidenced in the characters of Irene, William and Nina. Only Kevin appears to have true intentions for his art but is stymied by the crassness of those considered to be exceptional but are mediocre. As in all great artistic achievement, only time is the arbiter of true genius. Perhaps Kevin’s time for recognition will come long after Nina, Irene and William are dead.

The creative team for The Seagull/Woodstock, NY includes Derek McLane (scenic design) Qween Jean (costume design) Cha See (lighting design) Rob Milburn & Michael Bodeen (sound design) UnkleDave’s Fight-House (fight and intimacy director). For tickets and times go to the website https://thenewgroup.org/production/the-seagull-woodstock-ny/

‘Chekhov/Tolstoy Love Stories’ at The Mint Theatre, Two Masters’ Perspectives of Love, Adapted by Miles Malleson

Alexander Sokovikov, Brittany Anikka Liu in ‘The Artist,’ adapted by Miles Malleson from “An Artist’s Story” by Anton Chekhov, Chekhov/Tolstoy Love Stories (Maria Baranova)

“One of the most diversified talents in the British theatre,” Miles Malleson (1888-1969) was enamored of Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov, who had formed a bond in the latter years of their lives; Chekhov, the younger pre-deceased Tolstoy, the elder by six years–Tolstoy died in 1910. Admiration of these two great Russian writers inspired Malleson to create theatrical adaptations of short stories by Tolstoy and Chekhov. From Tolstoy’s parable “What Men Live By” Malleson adapted Michael. From Chekhov’s “An Artist’s Story,” Malleson configured The Artist.

The Mint Theatre Company has featured Malleson’s plays before (i.e. Unfaithfully Yours) considering Malleson to be a playwright worthy of recalling to our social theatrical remembrance. In the first offering of the season, The Mint has coupled the British playwright’s dramatic adaptations of Chekhov’s and Tolstoy’s one acts because their themes relate to love. In The Artist, directed by Jonathan Banks, Chekhov via Malleson ironically presents romantic love that never has the opportunity to blossom and rejuvenate, but is cut off before its time. In Michael directed by Jane Shaw, Tolstoy via Malleson uncovers truths related to the nature and power of agape love. The Mint Theatre Company’s production of Chekhov/Tolstoy Love Stories is currently at Theatre Row.

Presenting The Artist and Michael back-to-back offers the audience the opportunity to examine how each of the plays evokes themes about love, spirituality, redemption and revelation. Additionally, one identifies the contrasting social classes represented by the setting and characters of each one act. Each play identifies the perspective of the writers who were interested about what was accessible to the Russian social classes. Tolstoy, a nobleman often wrote about the worthiness of the lower classes who are represented by the characters in Michael. On the other hand Chekhov, whose grandfather was a serf, centered his greatest works on Russian gentry on the brink of an era of change (The Russian Revolution).

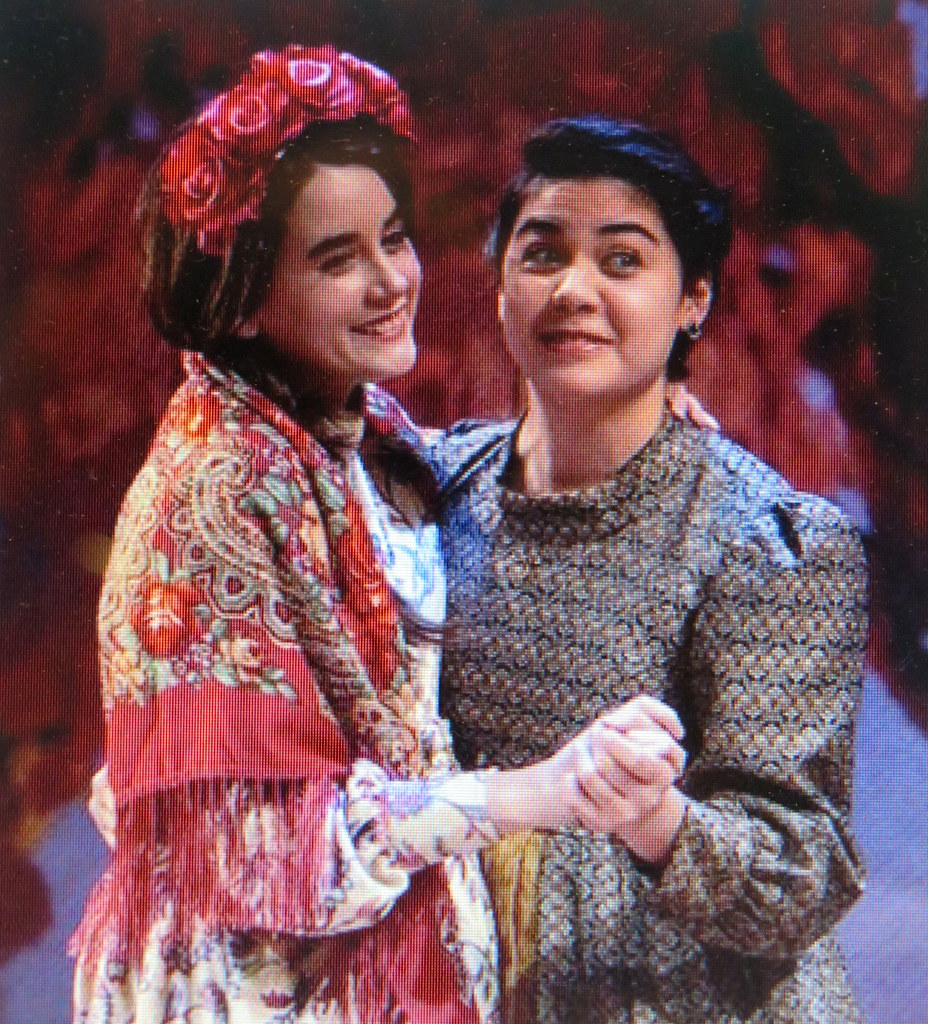

(L to R): Anna Lentz, Brittany Anikka Liu in ‘The Artist,’ adapted by Miles Malleson from “An Artist’s Story” by Anton Chekhov, Chekhov/Tolstoy Love Stories (Maria Baranova)

In keeping with Chekhov’s proclivities, The Artist takes place on a Russian estate run by a fine, elevated family of women who are intellectual and well regarded. These include the Mother (Katie Firth) and her two daughters. The elder daughter is the teacher Lidia (Brittany Anikka Liu) who is heavily involved with helping improve the status of the peasants. The youngest is the teenage dreamer Genya (Anna Lentz). An artist Nicov (portrayed by Alexander Sokovikov) visits often and the play opens as he paints his landscape while he interacts with Genya who listens to his philosophical justification of the importance of art over social reformation of the peasant class. Nicov and Lidia who represent antithetical views, argue continually. Thus, Nicov finds Genya’s unformed, youthful attentiveness an entrancement over Lidia’s disparagement of the useless function of Nicov’s art.

The characterizations of Nicov and Genya are reminiscent of Chekhov’s characters from his full-length plays, absent the conflict and tensions inherent in Chekhov’s full formed works. Malleson’s characterizations in The Artist are lukewarm and superficial. There is little heat and light as their should be when Nicov argues with Lidia to set up the drama and tension when he expresses his justifications to a sympathetic Genya with whom he falls in love and who returns his love.

The low-key tension and conflict of Malleson’s characterization is not helped by the lackluster performances. The spark of fire between Genya and Nicov that prompts the sardonic ending and Nicov’s felt and empathetic loss is missing. Nicov’s rant as delivered by Sokovikov is telling; Sokovikov does much of the heavy lifting with authentic responses from Katie Firth. Brittany Anikka Liu as the caring and forceful teacher/reformer in conflict with Nicov should be brighter, more ironic. Their interplay could even be darkly humorous. However, the love between Genya and Nicov is not believable. Thus, the impact of the Chekhovian sardonic ending is rendered impotent.

(L toR): Katie Firth, Vinie Burrows, Malik Reed, J. Paul Nicholas, in ‘Michael,’ adapted by Miles Malleson from “What Men Live By” by Leo Tolstoy, directed by Jane Shaw, ‘Chekhov/Tolstoy Love Stories’ (Maria Baranova)

Michael directed by Sound Designer Jane Shaw, making her directorial debut, employs more fluid light and music as the setting reverts to a peasant’s hut and the characters sing. The backdrop shifts. In The Artist, it is a painted tree filled with autumn leaves, signifying the season and symbolism of Nicov’s waning years. In Michael the design becomes the long, intricate white roots (interestingly lighting by Matthew Richards) of the tree. The symbolism of the lower classes is perhaps being suggested. It is the underclass (the tree’s roots) that supports and is the lifeblood of the middle and upper classes (the trunk, branches, leaves). Without the roots of the peasant class from which all humanity has derived, the upper classes can’t be sustained.

In Michael, the conflict arises when a homeless beggar (Malik Reed) is brought in by Simon (J. Paul Nicholas) and the wife (Katie Firth) must decide whether he should stay or be thrown out because they have barely enough for themselves and Aniuska (Vinie Burrows). The decision is made to let him stay. The scene shifts to a year later. We see the family is being sustained by Michael, the beggar who does not speak because he works as a cobbler for the peasant family. When a Russian Nobleman (Alexander Sokovikov) arrives and requires boots, the circumstances change. Michael makes a mistake with the boots, but it turns out to be a prescient action. That evening his learning is complete and finally Michael reveals who he is, why he is there and what he has learned about pity and empathy which is agape love. It is what we should live by.

The performances in Michael adhered more completely. Reed’s performance was soundly delivered undergirded by the ensemble. Malleson’s adaptation of the Tolstoy short story provided more dramatic tension and mystery. The staging and props added interest to engage the audience more completely, along with Oana Botez’s variable costuming, i.e. the nobleman’s coat and hat contrasted with the peasants’ outfits.

The pairing of the two one acts by the Russian writers who were contemporaries via Malleson is an enlightened decision if imperfectly rendered. It is the landed gentry in The Artist who remain unfulfilled by love, in effect harming the artist. They deprive him of rejuvenating love, and negatively impact his purpose to bring uplifting pleasure with his art. In Michael, the affirmation of the goodness of the peasant class (a Christian precept in the Beatitudes) is brought to them by Michael. He shares with them the wisdom that they have received through empathy/pity. It is the vitality of agape love that will sustain them.

In contrasting the two classes, the landed gentry is much worse off than the peasant class, a notion that Nicov suggests to Lidia to no avail. Lidia is convinced that (as in later years during the didactic polemic of the revolution) reform is imperative, art is useless. Meanwhile, the reforms and revolutions as they came did great harm which persists (one might argue) to this day. On the other hand making art is a necessity for the middle and upper classes to help them understand empathy and love, something the blessed poor, according to Tolstoy, are ready to receive and do take in as,the very potency which sustains them.

Chekhov/Tolstoy Love Stories runs until 14th March at Theatre Row (42nd Street). For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

Listed are the creative team: Roger Hanna (sets) Oana Botez (costumes) Matthew Richards (lights) Jane Shaw (original music and sound) Natalie carney (props).