Blog Archives

‘Evanston Salt Costs Climbing,’ Arbery’s Excellent Play is a Must-See

In the microcosm is the macrocosm. This is especially so in the setting Will Arbery presents in Evanston Salt Costs Climbing, the sardonic, metaphysical-realistic 95-minute play acutely directed by Danya Taymor, currently at the Signature Theatre presented by The New Group.

A key theme of Arbery’s exceptional work turns on the notion that the larger picture of what is happening resides in the details which human beings have a penchant for ignoring, though it is right before their eyes. Do we see the connections, or are we like the characters in this play, willfully unaware until a catastrophe results and it is too late to do anything about it? Arbery examines these themes in his thought-provoking, stylized work that suggests we cannot escape how we relate to our environment, no matter how much we attempt to obviate it. Indeed, Arbery points out that it is this blindness that has brought us to the brink of self-annihilation. Ironically, even standing on the brink looking down, we can’t manage to do what is needed to confront the human disaster that is unfolding before our eyes.

At the opening of Arbery’s play two truck driver forty-somethings, Peter (the superb Jeb Kreager), and Basil (Ken Leung is his vivacious side-kick), share their morning coffee before they take their rounds spreading salt to safe-guard the roads in and around Evanston, Illinois. We let this information slide away from us without giving it much thought. However, everything in Arbery’s play is profound and the characters’ lives and future are encompassed in the smallest detail of salt spreading. In that detail is reflected the wider invisible world that the characters sense is out there, both under the ground, pushing to break apart the sham infrastructure that cities have built for the purpose of commerce, or in the invisible world that hangs above in the ambient atmosphere pressing down on the characters to confound them and make them despondent.

The world that Arbery’s characters inhabit is representational. The action takes place in the environs of the Evanston “salt dome,” in the truck, and in Maiworm’s home, all staged with superb and symbolic minimalism by Matt Saunders’s scenic design, Isabella Byrd’s lighting design and Mikaal Sulaimon’s sound design. Before Peter and Basil begin their shift, Maiworm, the public works administrator who is their boss (the excellent Quincy Tyler Bernstine), stops in as she does each morning. Maiworm is astute and stays on top of the forward moving trends regarding the Green Movement. She understands the “larger picture” of the changing environmental conditions which impact their jobs and of which Peter and Basil remain unaware. Maiworm attempts to enlighten them by reading an article to them, the gist of which states that the record colder temperatures are requiring record levels of salt use. These are driving up the salt costs.

If we are paying attention, we understand the cause and effect of global warming and weather weirding indicated in this small detail of salt costs. After Maiworm reads the article, Peter says an article should be written about the fun he has with Basil driving in the truck. He doesn’t catch the “devil” in the details. In other words, he never makes the leap that the costs might impact his current job, his hours or salary. He assumes all will remain static in this job he’s had for twenty years.

Basil, who writes micro-fiction, ignores the underlying significance of the article for another reason. He tells Peter no one wants to read an article about their job because it has no “pull” or interest. The connection between Arbery as a writer and Basil is understated. It is as if Arbery twits himself about the intentional boring context of “salt costs climbing,” knowing that such a subject will not keep the audience engaged. However, Arbery is having us on. That is not what the play is about. And how the playwright cleverly connects this “detail” with its hidden significance making it dynamic and indelibly related to his characters is striking and horrifically revelatory to us.

Basil asks Maiworm about the impact of the increasing salt costs. Arbery reveals why Basil asks the question in the next scenes when we see that he and Maiworm have developed a covert sexual relationship unbeknownst to Peter. Thus, unlike Peter who doesn’t see or care about the symbolism behind the details, Basil is open to Maiworm’s thoughts and most probably encourages the direction of her decisions to feather her own nest and advance in her administrative position which must take into consideration the budget which includes the price of salt. However, on another level, he too misses the significance connecting the dots to climate change and colder weather which will create havoc if the powers that be (including Maiworm), don’t properly plan for it.

In a humorous scene that follows, we understand why Peter loves driving in the truck with Basil. They act silly and ridiculous, sharing “manly” antics as “roadies,” who do their job and maintain a friendly relationship, where they can cut loose and have a free-for all (which mostly entails cursing). Also, during this time Basil and Peter discuss more personal issues. Basil relates the dream he has of his grandmother who has told him, “Don’t let the Lady in Purple come near you.” He states, in the last part of the dream, The Lady in Purple does come near his grandmother, who dies. We intuit that the Purple Lady may be Death.

Additionally, Basil discusses that he ends up fusing with the Purple Lady and reverts to a dying little boy as the Purple Lady takes him. This, he tells Peter, happens during a time when cities are freezing and burning. Basil’s description is metaphoric and prescient in its representation of global warming, which he never mentions by name as if it doesn’t exist. By degrees, Arbery reveals how the events Basil describes in the dream come to fruition in his life in a mysterious way that merges phantasmagoria with reality later in the play.

Peter expresses that he is sad and his dreams are surrounding darkness and noise. This reflects Peter’s depression and suicidal thoughts. Basil, who has discussed Peter’s wanting to kill himself and kill his wife is concerned that Peter is in bad shape. Basil tells Maiworm about Peter and she vaguely comments she’ll watch out for him.

The dynamics of the interrelationships complicate as we learn more about Maiworm’s adopted daughter, Jane Jr., who suffers from depression and has suicidal thoughts like Peter. As Jane Jr. Rachel Sachnoff gives a fine, nuanced performance. of the only character who understands the impact of climate change. Maiworm’s concern for Jane Jr. includes trying to direct her interests by getting her to read Jane Jacobs’ book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Additionally, Maiworm encourages Jane Jr. to help others by singing to them at the nursing home. To make her feel needed, Maiworm uses Jane Jr. as her confidante. After a nightmare provoked by the suicide of the journalist who wrote the article Maiworm reads to Peter and Basil, Maiworm discusses her anxiety about Evanston. Maiworm tells Jane that she saw the dead rise from under the ground as the journalist fused with them. Then she segues the discussion to heated permeable pavers, the technology to make roads heat up so they can melt ice and snow to eliminate the use of salt and reduce costs.

Like all exceptional playwrights, Arbery reveals the trenchant themes by gradually through their connections. Eventually we learn one aspect why the heated permeable pavers might be a great solution. The salt is incredibly toxic and destructive to wildlife. Salt run-off pollutes the water table creating toxic blooms releasing poisonous chemical compounds and metals that kill animals and people.

Interestingly, this is the first we hear of such a technology, but not the last. We discover much later when Arbery connects the dots that Maiworm, to advance in her position, is part of the program to bring heated permeable pavers to Evanston, unbeknownst to Peter and Basil, whose jobs will become obsolete as a result. However, the implications of this Arbery does not make “visible” until after personal devastation occurs to each of the characters over the course of the three consecutive brutal winters in Illinois when the play takes place.

Arbery boxes in the characters who increasingly become dislocated through sadness and depression, indirectly caused by ignoring the moment of what is happening around them in the environment. Arbery indicates that though they don’t see the larger picture of the apocalyptic effects of climate change, in the unseen realm of the invisible world, it impacts them day and night. Jane Jr. is aware of this. It is mostly the cause of her depression and desire to end her life. She considers her Dad lucky that he died and doesn’t have to experience the impending doom that can be felt everywhere. Maiworm and others go about their lives as if nothing is happening. They live in a denial and that doesn’t quite work because they sense the coming destruction but don’t articulate its connection to what they feel is happening. Articulation is the beginning of recognition.

The unseen doom disturbs everyone. Peter’s suicidal thoughts continue and his situation worsens after his wife dies from an accident on the icy roads that didn’t have enough salt on them (presumably because less salt was used to defray costs). Fortunately, his daughter lives and they bond over Dominoes Pizza and watching the truck come to their door, a fun event for the six-year-old. Their relationship is the bright light in the play.

Maiworm’s guilt about Peter’s wife’s death is understated, but her behavior becomes more hyper and the overarching doom she senses increases in her life with Jane Jr. Additionally, the doom is in Basil’s dreams and shows up in his micro-fiction. When he is confronted with his past and inability to deal with it in his present, he is swallowed up (the Purple Lady makes an appearance). Basil joins the other dead in the earth metaphorically and physically fulfilling his nightmares. How Taymor and her team effect this is strange and dislocating, intensifying the play’s foreboding which becomes palpable to the audience.

Maiworm who could understand the impending doom of global warning’s impact on their lives, can only manage to live in the microcosm to fulfill her desire for advancement. She is the most blind and she blindsides others. Palliative measures to correct the dire future with “heated permeable pavers,” are too little too late. Caught up in the details, she ignores the “bigger picture.”

The climax of the encroachment of the unseen (the environment rebelling), upon the characters occurs toward the end of the play where Arbery delivers his key message delivered by a supernatural incarnation of a presence from the past, Jane Jacobs. As Jacobs, Ken Leung arises in black funereal dress. Without his accent he comes across with clear, precise anger and a clarion warning. Jane Jacobs suggests what we must do as human beings to face the oblivion of our own making. See the play; there is no spoiler alert.

Taymor’s direction of the actors is spot-on as they convey the suppressed doom in the tension and growing personal alarm in their dreams and confessions. All of the creative artists majestically bring together Arbery’s and Taymor’s vision of the dire consequence of the environment rebelling as an incarnate “thing.” Saunders, Byrd, Sulaiman and Sarafina Bush’s costume design, help to manifest terror in the atmosphere of the play through the suggestions of mysterious other-worldiness peeking through reality. We “get” the palpable danger human beings have created for themselves with their willful ignorance, negligence and dereliction of duty. That danger drives Maiworm, but because she ignores the signs and can’t translate what she feels into understanding, her obsession is misdirected. Caught up with the pavers for the future, Maiworm forgets to order salt for the present winter and they must hire others to do the job of salting the roads. She is rewarded for her incompetence as her advancement continues up the administrative chain.

The director and her team use at varying intensities darkness, shadows and light to great effect. Additionally, they alternate silence and loud sounds of the truck engines, screeching tires and grating sounds made by the raising and lowering of the warehouse garage doors. They employ storm sounds as well. These help to enhance the ominous atmosphere the characters feel and creates in us a growing dread. Also, the use of lighting and sound suggest the extremes of heat and cold and the eerie, weird quality of the environment as a being which humanity has monstrously shaped by its abuse. As a result of Taymor’s direction, Saunders, Bush, Byrd and Sulaiman’s artistry the nameless stark, terrible becomes real and the playwright’s themes hit home. Their prodigious efforts combined with the actors’ authenticity create memorable live theater that should not be missed.

For tickets and times go to their website https://thenewgroup.org/production/evanston-salt-costs-climbing/

‘Pass Over’ at the August Wilson Theatre is Glorious

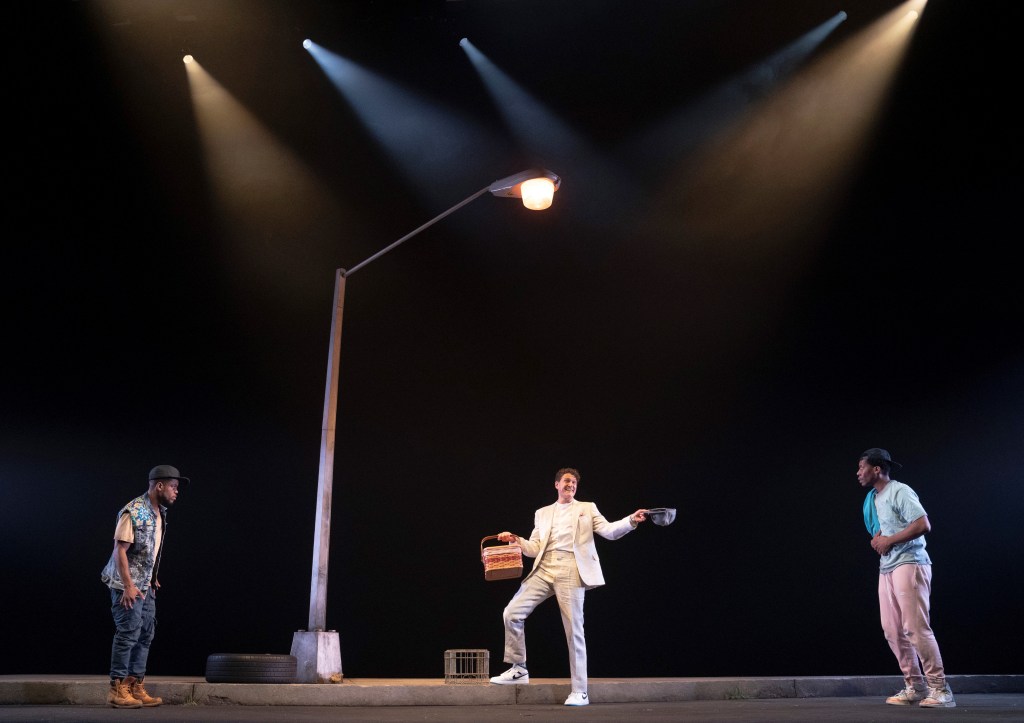

Two men standing on a desolate street corner with a lamppost shining on a blasted, deserted, space save for a garbage can, a patch of weeds, a tire, a wire milk carton. Such is the material/empirical setting reminiscent in its isolation and abstract loneliness of Samuel Beckett’s setting in ‘Waiting For Godot.’ Likewise the comedic and clown-like Moses (the brilliant Jon Michael Hill) and his Homie, clowning sidekick Kitch (the brilliant Namir Smallwood) appear similar to Vladimir and Estragon. However, they are not. They are black. And where Vladimir and Estragon “wait,” unafraid, bored, wiling away the hours, Moses and Kitch exist in a hellish landscape afraid of death at the hands of the “PoPos,” shorthand for police.

Whether one has seen Beckett’s Godot or not, doesn’t matter. The isolation of these two individuals and their express desires to leave this heartless existence that holds the terror of black men dying by a simulated “justice” which is tantamount to the injustice of lynching is conveyed with empathy and poignancy by the creative team of actors and director Danya Taymor. With acute care, emotional grist, comedic genius and dynamic drama, they bring to stark, felt life, Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu’s haunting, memorable dialogue in Pass Over, currently running at the August Wilson Theatre in a cool, streamlined no intermission production.

When we first meet the likable Moses and Kitch, we understand their camaraderie and support for one another, as well as the similarity of their desires, fantasizing about the finer things of a luxurious, material, elite lifestyle. Though Moses is the leader and Kitch is his follower and admirer, their synchronicity and dependency is clear, for they wish to “pass over,” to get to the “promised land,” the “land of milk and honey” represented by the “American Dream.”

And whether we have eaten lobster or drank Crystal, like they wish to, we, too, have craved the finer things of life and may even feel a sense of superiority that we have experienced them, where these impoverished of the ghetto block can only entertain themselves and each other by dreaming about such extravagances in a humorous and ironic game which has become a way of bonding between them.

Fifteen minutes in to the thrust and parry of humor, the gaming is interrupted by a Pavlovian signal that has brainwashed them to fear: the stage floods momentarily with a steely light and a dull, blaring warning sound. (It reminded me of Steven Spielberg’s 2005 film War of the Worlds, when there sounds a far-reaching alarm announcing the aliens’ presence.) We learn later that Moses and Kitch recognize this alarm as the sound of death; that another black friend or acquaintance in their neighborhood has been killed by police. They cower and crouch in fear until the light and sound normalizes to the stasis of desolation, and once again they return to humor and the grace of planning to escape and go somewhere where they can live free from fear in a greater abundance of prosperity than their current existence.

However, there are two caveats. They must elude the PoPos, as Moses led the Israelites to elude the angel of death which “passed over” the the First Born if the blood of the lamb was on the doorposts of the Israelites’ homes. Secondly, the PoPos expect them to remain on the block to never escape their oppression and misery. Thus, they are free only in their games, humor and imagination, while their physical bodies are subject to the reality of their dire existence with the threat of death hanging over their lives. Will they be able to “pass over” and escape death? The symbolism is spiritual with possibilities for escaping all of what the playwright infers elements of the death state is in this life.

Into their ghetto corner (which the playwright suggests symbolizes as historical oppression and redemption-a river’s edge, a plantation, a desert city built by slaves and a new world on the horizon) comes Mister who slips up and calls himself Master (the wonderful Gabriel Ebert). Taymor has him ironically dressed in a white suit and vest, such as gentlemen of the Old South used to wear on or off the plantation. Mister, intending to visit his ill mother with a picnic basket of food, inexplicably gets lost and arrives with his bounty to the ghetto block.

At first Moses, whom his religion teacher encouraged to live up to his namesake, the Biblical Moses, proudly eschews Mister’s offer of food charity, though both he and Kitch are hungry. However, sociable, “good-natured” Mister cajoles and tempts them. And after he massages their egos with charm and humility, he shares some of the delicious food in his basket with Moses and Kitch in a wonderfully humorous staged scene.

We note the roles between the individuals and hints of seduction and exploitation, expecting some catastrophe, however, Nwandu has tricks up her sleeve and the situation with Mister is as it appears. Mister worms his way into their hearts and they become friendly. And for a fascinating moment they forget about “getting off the block,” and being all they can be, lulled by the food. Intriguingly, Mister chides them for abusing their use of the “N” word which he cannot use, because as Moses suggests, he doesn’t own that word.

It is an ironic gesture since it is perhaps the only “thing” Mister doesn’t “own,” as a representative of the dominant oppressor race. Though Mister doesn’t “own” their black identity which they have accepted as their own, is it something which is good for them or is it another trick of oppression? After Mister leaves, Moses and Kitch realize that adopting that identity is a trick of the white culture and the PoPos, for by inference, the “N” label associates with low-down and/or slovenly criminal behavior, regardless of whether they are deserving of such labels or not. Ironically, they have proudly accepted that term as their identity, but it has resulted in black male deaths at the hands of the police.

Deciding to cover for themselves, using Mister’s gentile manners, they avoid trouble, when Ossifer (a police officer played by Gabriel Ebert who is the different side of the same coin as Mister) shows up. Moses and Kitch become “gentlemen” in word and action, imitating Mister. It works. Ossifer leaves them alone and protects them as culturally “white” until Kitch slips up and uses the “N” word triggering the brutality of the police officer who confronts them as their oppressor to control, belittle and demean. Under these circumstances we feel the depressive desolation of the historical and current inferior “slave.” And Ossifer terrorizes them reminding them that their lives are only useful for living in fear and misery as “the controlled.” The only respite Moses and Kitch have is the humor and hope Kitch and Moses stir up within themselves and share with each other to make existence bearable until they can “pass over.”

In an amazing turning point, Nwandu clarifies a new meaning for the term Moses references from the Bible, “pass over.” It is a spiritual one that Moses convinces Kitch they must now seek, no longer wanting to deal with the despair and long trial of a desolate existence.

Taymor, shepherding Hill, Smallwood and Ebert creates extreme tension throughout. Especially when Ebert as Mister and Ossifer shows up. The atmosphere is that of a pressure cooker sizzling until it seethes into an explosion which does occur. We, like Moses and Kitch, expect the blast after every joke, around every game they play, especially when the alarm sounds and lights flare up that the PoPos have killed another black man. Nwandu cleverly distorts the thrust of the heat and danger providing extraordinary twists in the turn of evolving events. These become revelatory, magical and lead to the unexpected and heartfelt.

The beauty of the conclusion is in its realization of a return to an ideal which isn’t actually some pie in the sky fantasy, but is present and real. In the production it occurs with the help of and extraordinary supernatural intervention as happened to the Biblical Moses. Taking one step forward after another, Moses, Kitch and Ossifer (a reborn Christopher) are released and the imagined consciousness comes into being. However, the lure of what’s past beckons. One must not turn around to be enticed, or everything will be lost in the material plane where the human race has crashed and burned for millennia.

Pass Over is a must see for its fantastic performances, its uniqueness, its joy, despair, thematic truths and its wonderful faith and hope in human nature. I could not help but be gratified that there were no female characters. Their absence is lyrically pointed. The production is mesmerizing and I have nothing but praise for how the playwright, director and actors connected with the truth of what we face as a multifaceted and diverse society that is desperately crying out for healing and redemption. But as Nwandu suggests, the promised land is already here. We must look to our own inner strengths and step out to cross that “river”and never turn back.

Kudos to the creative team that made this production fly and whose effects helped to send chills down my spine and tears down my face. They include Wilson Chin (scenic design) Sarafina Bush (costume design) Marcus Doshi (lighting design) and Justin Ellington (sound design). Pass Over runs until the 10th of October. This is one you cannot miss. For tickets and times go to the Pass Over website by clicking HERE.

‘Heroes of the Fourth Turning’ by Will Arbery at Playwrights Horizons

Jeb Kreager, Julia McDermott, Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

John Zdrojeski, Julia McDermott in Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

It’s seven years after you’ve graduated from college. What do you do if you are adrift, emotionally miserable and/or in physical pain? What if cocaine, alcohol, social media obsessions, abstinence from sex, indulgence in sex, and your Catholicism isn’t helping you find your way? Do you find something else to believe in to help you escape from the labyrinth of conundrums and foreboding demon thoughts plaguing your life?

Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning in a production at Playwrights Horizons ably directed by Danya Taymor discloses the inner world of the right wing religious. In his entertaining and profound examination of conservative-minded friends and alumni from a small, Catholic college who gather for a party, we get to see an interesting portrait of conservative “types,” who are akin to liberals in dishing the rhetoric. To his credit Arbery gives grist to the argument that beyond the cant are the issues that pertain to every American. Whether liberal or conservative, all have the need to belong, to care and love, and to make a way where there is no apparent way to traverse the noise and cacophony that creates the social, political divide currently in our nation.

John Zdrojeski, Zoë Winters Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

How each of the friends attempts to survive “out there” in the cruel, “evil” world fascinates. During the evening mini reunion on the occasion of celebrating Emily’s mom’s accepting the presidency of their alma mater, Emily (Julia McDermott), Kevin (John Zdrojeski), Justin (Jeb Kreager), and Teresa (Zoë Winters), explain who they’ve become or not become in the seven years since they’ve graduated. Teresa, a rebel during her college years, has become more right-wing conservative than ever, embracing Steve Bannon, Breitbart and Trump with gusto. The others have “laid low” in retreat in Wyoming and Oklahoma, holding jobs they either despise or “put up with,” until they get something better.

Zoë Winters, Jeb Kreager, Julia McDermott, Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

Zoë Winters portrays Teresa, the feisty, determined, “assured,” conspiracy-theorist supporter with annoying certainty and hyper-vitality, as she explains the next phase of American history to the others. She does this by summarizing a book which posits the Strauss-Howe Generational Theory. Emily, Teresa and Kevin fit into the millennial segment which lends its title to the play: the fourth turning/hero cycle. As she insists that her friends are the hero archetypes laid out in Generations: The History of America’s Future: 1584-2069, she suggests they must embrace their inner/outer hero and get ready for the coming “civil war.”

John Zdrojeski, Julia McDermott in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

For different reasons Emily and Kevin find Teresa’s explanation of the “Fourth Turning” conceptualization doubtful for their lives. Kevin’s self-loathing and miserable weaknesses belie heroism. He is too full of self-torture and denigration to get out of himself to help another or take a stand for a conservative polemic to fight the liberal enemy in a civil war. Emily is crippled by the pain of her disease. We discover later in the play that she has questions about the conservatism she once embraced. The civil war polemic only seems possible for Justin (Jeb Kreager), who was in the military. Though Justin is not the “Hero” archetype, but is a “Nomad,” he later in the evening expresses that he thinks the conspiracy mantra “there will be a civil war,” proclaimed for decades by alternative right websites will happen.

John Zdrojeski, Zoë Winters, Jeb Kreager, Michele Pawk, Julia Mermott in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

Arbery has targeted their conversations with credibility and accuracy and the actors are authentic in their nuanced portrayals. As Kevin, John Zdrojeski becomes more drunk, humorous and emotionally outrageous as the night progresses. His behavior shocks for a supposed Catholic, until we understand Kevin doubts his religion’s tenets, especially abstinence before marriage. To a great extent he has been crippled emotionally by doubt, double-mindedness and the abject boredom he experiences with his job in Oklahoma. Also, he admits an addiction to Social Media. Zdrojeski projects Kevin’s confusion and self-loathing victimization with pathos and humor. But we can’t quite feel sorry for him because he is responsible for his morass and appears to enjoy reveling in with his friends. Teresa suggests this is his typical behavior.

The friends wait for the arrival of Gina (Michele Pawk), Emily’s mom’s, to congratulate her on becoming president of their old alma mater, Catholic Transfiguration College of Wyoming. As they wait, they drink, get drunk and catch up with each other, reaffirming their friendships from the past. They discuss and reflect upon the decisions that brought them to Catholic Transfiguration College. We note their conservative, religious views about life, family and politics. Their confusion, sense of impending doom and lack of hope for the future are obvious emotional states. This is an irony for Catholics, whose hope should reside with the birth of Christ and the resurrection. Clearly, they are not exercising the spiritual component of their faith, alluded to in Gina’s speech and in Kevin’s quoting of Wordsworth’s poem “The World is Too Much With Us.” They’ve allowed the material and carnal to overtake the spiritual dimension and thus are depressed and filled with doubt.

(L to R): John Zdrojeski, Michele Pawk, Jeb Kreager, in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

In representing the conservative views of these individuals, the playwright culls talking points from right-wing media and blogs which Teresa references to Gina when Gina finally arrives. The fact that right-wing conservatism construes violent fighters as heroes is a conflated, limited view. Indeed, to see oneself as a hero and embrace that role is not even an act which true heroes (i.e. firemen, doctors in war zones) saving lives perceive for themselves. It is rhetoric. And Teresa, to empower herself and impress her old friends, speaks it as polemic. Her discussion is not really appropriate to inspire comfortable light conversation at a party. Indeed, her talk is done to solidify herself in the firmament of fantastical belief and remove any oblivion of her own doubts about her life. She and Justin who was in the military particularly rail against liberals, the LGBTQ community, Black Lives Matter, etc.

(L to R): Michele Pawk, John Zdrojeski, Zoë Winters, Heroes of the Fourth Turning, by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

Interestingly, Gina blows up Teresa’s cant when she finally arrives to receive the friends’ congratulations. However, they are not quite ready for Gina’s rhetorical response which is a convolution of conservative and liberal ideas that loop in on themselves again and again and defy political labeling. But Gina separates out the illogic of each of their positions. She disavows Justin’s need for guns on campus and decries the conspiracy of the upcoming “civil war.” She implies that Bannon and his like-minded are hacks, and she disavows Trump to the shock of Teresa. At the end of the evening, she pronounces that she is disappointed in the education they have received at their school, believing the college has failed them.

Jeb Kreager, Julia McDermott, in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

The night of celebration becomes a night of upheaval for Emily, Justin, Kevin and even the staunchly “certain” Teresa who will in the next decade most probably change her views a number of times to suit her determination that she has a handle on the great narrative of “reality.” But in truth as we watch these friends founder through the labyrinth of sublimely complex political, social and cultural convergences they discuss and refer to, it becomes obvious that they have been dislocated from their comfortable conservatism that categorically defined the world for them when they began college.

(L to R): Zoë Winters. Michele Pawk in Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery (Joan Marcus)

The irony is that when Gina comes and joins their conversation and smacks down each of their beliefs, especially Teresa’s, we settle back watching the imbroglio that Arbery has wrought. Indeed, we wonder at Gina’s convoluted logic and justifications. That she would give Kevin a job in admissions is a dark irony of misjudgment. He appears the least directed to help others in the admissions process. Though they say their goodbyes with love, Justin and Emily remain in darkness. There is no comfort to be found. There is only the continuation of a foreboding reckoning.

The strongest dynamic of the play resides in the conflicts when Arbery has the friends go at each other after their initial easy reaffirmation of friendships. Ironically, the community they attempt to create falls apart driven by what is devouring each of them inside. It is then that personal flaws they’ve discussed manifest and the hell they face within spills out. Justin’s is humorously eerie. Emily’s comes in the form of fury at whom she deals with in her job and the resident demon of pain in her body. Teresa fears she is making a mistake getting married, and Kevin can’t come to the end of himself.

The tempest between and among the individuals and their inner conflicts reflects a currency for our times and is welcome fodder for entertainment. Arbery with the subtle direction of Taymor has succeeded in extending a hand across the divide of national uproar between left and right with his human, flawed characters. The actors in this ensemble are superb and hit powerful emotional notes with spot-on nuances between humor and profound drama.

This is a play you must see for its shining performances, its topics, the rhetoric-exceptionally fashioned by the playwright and its surprises in characterization. The conclusion is chilling as it expands to the mythic. Noted are the design team: Sarafina Bush (costumes), Isabella Byrd (lighting), Justin Ellington (sound), J. David Brimmer (fight director).

Heroes of the Fourth Turning runs with no intermission at Playwrights Horizons (416 West 42nd Street between 8th and 9th). For tickets and times go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

t