Blog Archives

Caryl Churchill Strikes Again in a Provocative Suite of Metaphoric One-acts: Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Metaphor rides high in the four one-act offerings thematically threaded by British playwright Caryl Churchill. The suite is currently playing at The Public Theater until May 11th. Directed by James Macdonald, Churchill’s most recent collection integrates poetry, surrealism and “mundane reality” with a twist to represent the precariousness of our psyches in an incomprehensible world that populates the humorous and the horrible simultaneously.

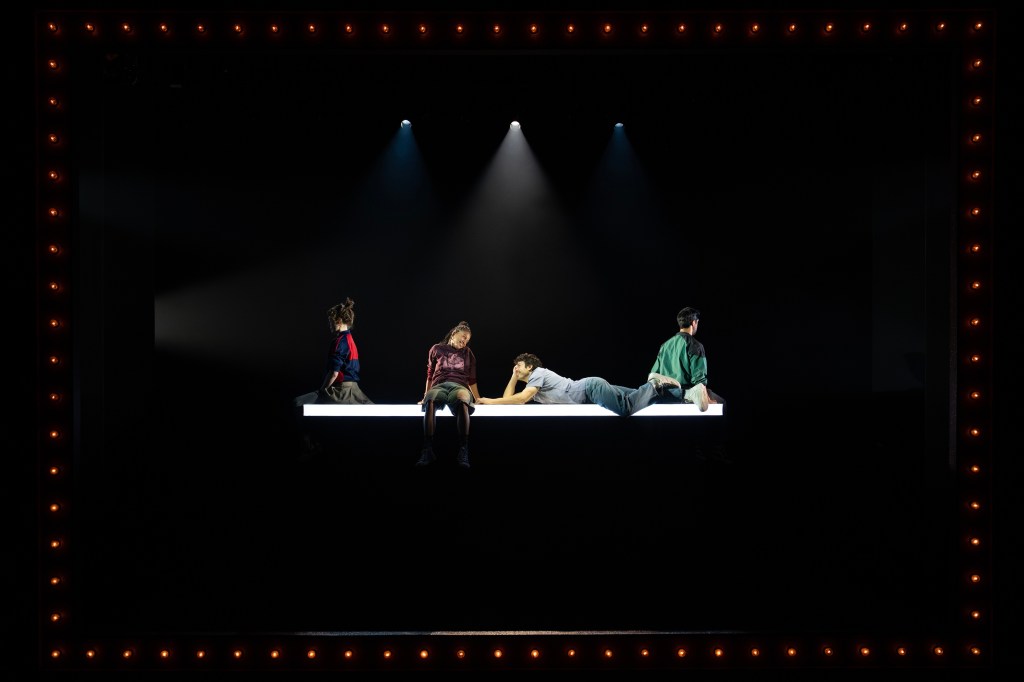

“GLASS” is a fairy-tale-like playlet that opens onto a lighted platform amidst darkness (scenic design by Miriam Buether), which we discover is a mantlepiece that holds objects. The protagonist is a girl of transparent glass (AyanaWorkman). According to the stage directions, “There should be no attempt to make the glass girl look as if she is made of glass. She looks like people look.” We meet her with others who are her jealous rivals, (an antique clock, a plastic red dog, a vase). Though the “glass girl” doesn’t seem to care to compete, the others humorously swipe at each other about who is the most useful, beautiful or valuable.

All look like people, suggesting a conceit. One interpretation might be that objectified humans come to believe in their own “grand” objectification. Other humans, aware of themselves, are transparently fragile, which can result in tragedy. Though Churchill’s meaning is opaque, the playwright adds layers. When Ayana Workman’s character is with schoolgirls, who persecute her and make her cry, her pain is visible both inside and out. Her vulnerability attracts a boy (Japhet Balaban), who becomes her friend and confidante. He whispers a story of his life with his father since he was seven. Though his whispers are not audible, we imagine the worst. Yet, we are shocked when the glass girl explains what happens to him which has a devastating impact on her.

The theme of fragility suggested in “GLASS,” is continued as an ironic reversal in “GODS,” after circus performer Junru Wang, presents stunning acrobatic maneuvers on handstand canes. The interlude with lyrical music provides time to reflect about aspects of life which require balance that only comes with training and practice as Junru Wang exhibits.

In “GODS,” Churchill casts the Gods of Greek and Roman mythology as the vulnerable ones. They unleashed the Furies to punish brutal humankind to no avail, then recalled them because humans never tire of bloodthirsty murders, wars, rampages. Deirdre O’Connell embodies all of the Gods. She sits suspended mid stage on a fluffy, white cloud surrounded by darkness, haranguing the audience in a stream of consciousness rant about the bloodletting, familial murders, intrigues, wars and cannibalism.

In a summary of bloody acts, O’Connell’s Gods admit they encouraged the brutality with curses and liked watching the results. But now in a humorous and ironic twist, they don’t like it. Furthermore, they wash their hands of the killing, because they don’t even exist. That is to say humans attribute their own monstrous behavior to the Gods instead of accepting responsibility for their own heinous acts. By the conclusion O’Connell’s Gods scream and plead, “He kills his son for the gods to eat and we say no don’t do that it’s enough we don’t like it now don’t do it we say stop please.” The Gods’ point is made. The audience agrees. The maniacal being, a human creation, haplessly protests its creators, knowing the bloodshed and murders will continue. If the gods had ultimate control would humanity be peaceable? Churchill’s irony is devastating.

Circus performer Maddox Morfit-Tighe creates the second interlude as he juggles with clubs and performs acrobatic movements. Macdonald positions both circus performers in the “pit” in front of proscenium using Isabella Byrd’s lighting design for dramatic effect. Churchill’s irony about humankind as performers who juggle and balance themselves in the tragicomical circle of life continues the thematic thread of vulnerability and fragility.

In “WHAT IF IF ONLY” a husband’s (Sathya Sridharan) grief over his wife’s death is so intense that his desire touches the spiritual realm, and the possibility of her return seems imminent when a “being” shows up. However, his suffering has evoked a ghost of “the dead future.” The being brings the horrific understanding that his wife is forever gone, subject to her vulnerable mortality. What is left are the illimitable future possibilities. But when the being suggests that he tries to make a possibility happen, he claims he doesn’t know how. His grief has cut off his ability to even conceive of a future without his wife.

No matter, a child of the future (Ruby Blaut), shows up. Though he ignores the child, she affirms she is going to happen. As we daily ignore our vulnerable, mortal flesh to live, the future will happen, until we die. Churchill frames life as hope with possibility that we must let happen.

After the intermission Macdonald presents Churchill’s uncharacteristic, humorously domestic one-act “IMP.” The last play continues the thematic threads but buries them in the ordinary and humorous. The significance of the title manifests well into the play development after we learn the back story of two cousins who live together, Dot (O’Connell), and Jimmy (John Ellison Conlee), and their two visitors, niece Niamh (Adelind Horan), from Ireland, and local homeless man Rob (Japhet Balaban). During Rob’s visit with Jimmy, since Rob doesn’t want to discuss any personal details about himself or the possibility of a relationship forming between himself and Niamh, Jimmy decides to share a family secret. Dot believes she captured an imp that is in a wine bottle capped with a cork.

Though Jimmy claims not to believe the imp exists, at Bob’s suggestion, he uncorks the bottle. In the next six scenes we watch to see if anything changes in the lives of these individuals and are especially appalled when Dot wishes evil on Rob via the imp when she discovers that Niamh and Rob split up. We discover the imp’s power by the conclusion. However, the act of Dot’s powerlessness and vulnerability in projecting her own malevolent wishes through a mythic creation to avenge a loved one is pure Churchill. This is especially so because in this homely environment where nothing unusual happens, there is the understanding that people activate myths. Indeed, our beliefs may comfort, but on another level may entrap and even destroy.

Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp.

Running time is 2 hours15 minutes with one intermission, through May 11th at the Public Theater publictheater.org.

‘Infinite Life’ by Annie Baker, a Review

The premise of award-winning Annie Baker’s play Infinite Life, premiering off-Broadway at Atlantic Theater Company’s Linda Gross Theater, is that pain is the crux of life. Directed by James Macdonald, the production focuses on individuals who deal with pain along a continuum from heart-wrenching emotional angst to stoical virtuousness. Regardless of how they confront their suffering, it is never, ever easy. Indeed, most of the time, the pain endured by the characters we meet in Baker’s play foments a nightmare world of shattering identities, where the characters can’t recognize themselves through the agony.

Baker exemplifies this concept superbly with her characterization of Sofi (Christina Kirk) at various segments throughout her ironic, profound work. Through Sofi’s emotional outbursts and wild, antic, verbal expressions of sexuality, we understand the humiliation and self-loathing that often accompanies the resistance to pain’s annihilation of self, which Sofi and other patients acknowledge.

At the top of the play, Sofi converses with Eileen (Marylouise Burke), who walks very very slowly as she joins Sofi in the resting area where they become acquainted. It is then, we begin to understand where they are and why, when Eileen asks about Sofi’s fasting. Armed with a book she is reading, George Elliot’s Daniel Deronda, (an ironic, related, situational reference), Sofi answers Eileen’s simple questions haltingly, which indicates she may not want her “peace” or privacy disturbed by the talkative, fellow patient.

With just a smidgen of dialogue, Baker introduces elements which arise throughout the play and form the nexus around which Baker invites salient questions about consciousness and the synergy of mind, body, psyche and emotions. Key questions encompass the philosophical conundrum of what the characters must do with and for themselves in this “infinite life” of self, from which there is no escape, and fleeting happiness exists in an unwitting past where there was no physical torment caused by disease.

In a slow, dense, heavy unspooling, Baker introduces us to six characters, five women and one man. The women are dressed in casual workout clothes, loungewear and flowing tops (Ásta Bennie Hostetter’s costumes). These indicate the state of treatment they are in, whether “working it,” seeking comfort or relaxing.

The setting is an unadorned, outdoor space with scruffy, lounge chairs they recline on, bordered by a cheap, latticed, concrete block wall (scenic design by dots). We come to learn this area is the patio or balcony of an alternative healing clinic, that was once a motel. The entire production takes place in this outdoor area that overlooks a parking lot with a bakery wafting aromas of fresh bread from across the street that the characters comment on.

Here, as they “take the air, sun and dark night sky,” the women and man who have various maladies share the unifying, dire reality that they are in terrific pain with illnesses that have no solid cure and will probably reoccur. A variety of upbeat attitudes, modified hopelessness, positivity and stoicism resound through their conversations to distract themselves and each other. The conversations reveal the tip of the iceberg, below which the pain they endure alone, unseen, fills their days and nights.

Admirably, perhaps, these patients look to mitigate and heal seemingly without chemicals (no Oxycontin) or conventional medical methods. Nelson (Pete Simpson), who arrives late to the sunbathing scene, shirtless and attractive, has colon cancer which returned after surgery and mainstream treatment. He opts to try the alternative therapies at the clinic for twenty-four days, he confides to Sofi. He’s determined to follow in the footsteps of a friend who received relief at the clinic.

Sofi graphically shares the type of pain she has that involves her sex organs and has no cure which intrigues Nelson as a weird “come on.” Perhaps it is, but it is also her intriguing and extended cry for help in their scenes toward the play’s end. Likewise, Nelson shares graphic, intimate experiences with his colon blockage that involve tasting his own fecal matter. They share their nightmare world and appear to comfort one another, for a moment in time.

Their scenes together become a high point that intimates the possibility of intimacy but dead ends as far as we see and know. Both characters skirt the edges of hopelessness. Sofi doesn’t think she can make it through what the pain requires of her to sustain, which includes the dissolution of her marriage because of a mistake she made. Nelson implies that if his condition remains static, he will plunge back into radiation treatment and conventional medicine. Both appear hapless, buffeted by the circumstances of their body, beyond which they may or may not ever regain an illusion of control.

Through their journey toward relief, the patients have signed on to be put through their paces. The regimen and therapy that Sofi, Eileen, Elaine (Brenda Pressley), Ginnie (Kristine Nielsen), Yvette (Mia Katigbak) and Nelson have agreed to, require they fast, sleep, rest outdoors, drink concoctions fashioned for their various conditions, do passive activities like read, meditate, pray and, if they wish, rest and commune with each other in the common area, if their will and energy occasion it.

Over the first few days, each woman shares her condition and counsels Sofi, the newest arrival in their midst. For example they discuss that the second and third days are the worst, that after she pukes bile she’ll feel better, and she’ll get past her hunger and grow used to the fasting, etc. Narrating the time passages almost at random, Sofi announces hours or minute differentials before the next conversational scene occurs, as the women continue seamlessly sharing from where they left off hours before. Director James Macdonald’s staging is symbolically passive and static.

The effect is a linear, unceasing continuation as though time is not passing at all, and we are in an ever present present, a side effect of horrific pain. However, Sofi and lighting designer Isabella Byrd’s lighting, which switches from sunlight to darkness, disabuse us that time is standing still for these sufferers. Time marches on and drags them and their pain with it, as Sofi reminds us, though nothing appears to be happening on a material level. On a cellular, spiritual level it may be quite a different story; perhaps there is healing and mitigation though it isn’t readily visible to the naked eye.

As we become more familiar with Baker’s pain managers, we learn they are at various stages of their treatment, and marvel that some, like Yvette, are alive, despite their multiple conditions. Hers are numerous with exotic names along with the medication she lists was given to her during and after her bladder removal, cancers, catheterizations, and chemical poisoning side effects from all the doctors’ interventions.

Interestingly, Yvette is the most stoic and accepting that she will face whatever agony comes her way. The exhaustive list of her illnesses is an affirmation of the human will to “make it through” to the next day, where she will continue to suffer. There is valor in that, as Yvette’s will persists. Sofi is her counterpoint and is desperate and potentially, if things don’t change, suicidal.

The women’s conversation is banal and reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s plays, which find characters waiting opaquely and uncertainly, though here, Baker defines that the treasure they wait for is healing, an absence of the excruciating terror in their physical bodies. Yet, though we watch and listen to what appears to be stasis, sometimes, the characters in spite of themselves, are humorous and ridiculous.

This is especially so when sexual topics arise and go nowhere useful, and some raw sexual language that Sofi uses unwittingly discomforts Eileen, who is a Christian. For example Mia’s Yvette discusses her second cousin who narrates pornography online for the blind, which prompts a discussion of how it is possible for the blind to react to described sexual acts.

In another segment Ginnie initiates a conversation about a pirate who rapes a young girl who commits suicide. The story is part of a philosophical teaching taken from one of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh’s books. The provocative question Ginnie asks all to think about concerns the Zen Master’s statement that people are the pirate and the rape victim. The thought that are are capable of equal parts of sadism and masochism spirals into absurd and clever responses in a beautifully paced repartee between Nielsen’s Ginnie and Mia’s Yvette.

Following Baker’s “less is more,” undramatic plot where little appears to happen, director James Macdonald’s vision synchronizes with a minimalist, spare, unremarkable set design (dots design studio) befitting a place of transition, a way station after which patients will move back to their homes to continue healing, seeking treatment or dying. The overall shabbiness of the place, coinciding with the external, static situation of pain endurance, indicates the de-emphasis on the material surroundings. Instead, the focus is on the spiritual, deeper consciousness where the inner healing takes place sight unseen and manifests physically when the characters leave, for they’ve achieved some sort of relief. Perhaps some, but not all. Some are still there and in hell.

The minimalist structure is the receptacle for the weighty philosophical, tinged with metaphysical ideas that the characters express between the arduous moments of waiting. Baker has them burst out with pithy statements universal to us all, reminding us that beneath the ordinary, difficult, daily hours each of us sustains, there is the painful construct that we are dying while we’re living. The glorious part is the absence of pain. Eileen says in a difficult moment of agony, “a minute of this is an infinity.” The unfortunate part is if illness and pain comes, there is the bracing life lesson that sickness reminds the sufferer. It is what Beckett’s character said in Endgame, and a statement he repeated. “You’re on earth. There’s no cure for that.”

Baker is fascinating upon reflection, reading the script. With the live production the dialogue was sounded spottily because of the theater’s acoustics, the unequally distributed sound design and low conversational tones of the actors, during various segments. Audience left remained in stark silence while audience right rippled with responses of laughter, throughout during the production I saw in preview. Pulitzer Prize winner Baker is known for her pauses and silences in the dynamic among the characters, which in this play added gravity and profound undercurrents. However, in the performance, the silences were noticeably from audience left as audience right chuckled in delight.

The lack of audience reaction because of sound design difficulties was obvious. Interior pain is more easily expressed on film with close-ups. In an attempt to express their pain’s trembling terror, some actors chose to moderate their projection downward into quietude. Throughout, Mia Katigbak and Kristine Nielsen could be heard. Marylouise Burke managed to get around the conversational tones with a haspy, raspy voice which carried.

Similarly, the other superb actors were present during their important moments that conveyed the play’s themes. However, the audio was not sustained, as it should have been. Ironically, I noted even the young man seated next to me leaned forward on the edge of his seat, and not because the suspense was overwhelming. He was straining to hear. Apparently, this is not a problem for director James Macdonald, though it was for audience members whose experience was less than stellar, unfortunately, for a play which, after its reading, I found to be exceptional, profound and thought-provoking.

Infinite Life runs at Atlantic Theater Company. It is a co-production with the National Theatre. For tickets visit the Box Office at the Linda Gross Theater on 20th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues. Or go to their website https://web.ovationtix.com/trs/cal/34237?sitePreference=normal

The Mindblasting Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano Cave to Primal Hatreds and Private Desolations in Sam Shepard’s ‘True West’

(L to R): Ethan Hawke, Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

True West by Sam Shepard is a tour de force which easily reveals actors’ talents or their infelicities. Indeed, it may be a devastating on-stage nightmare if the actors’ skills do not resonate with a fluid “moment-to-moment” dynamic that sits precariously on the knife-edge of emotional chaos and crisis. This is especially so in Act II of Shepard’s True West which is currently in revival at the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street, starring the consummate Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano. Both actors rise to the pinnacle of their skills surfing their own moment-to-moment impulses in this sense-memory tearing, emotional slug-fest of a play about siblings. This is a glorious, shattering production thanks to Hawke and Dano who once more prove to be among the great actors of their generation. If Shepard is apprised of this production in another realm of consciousness, surely he is thrilled.

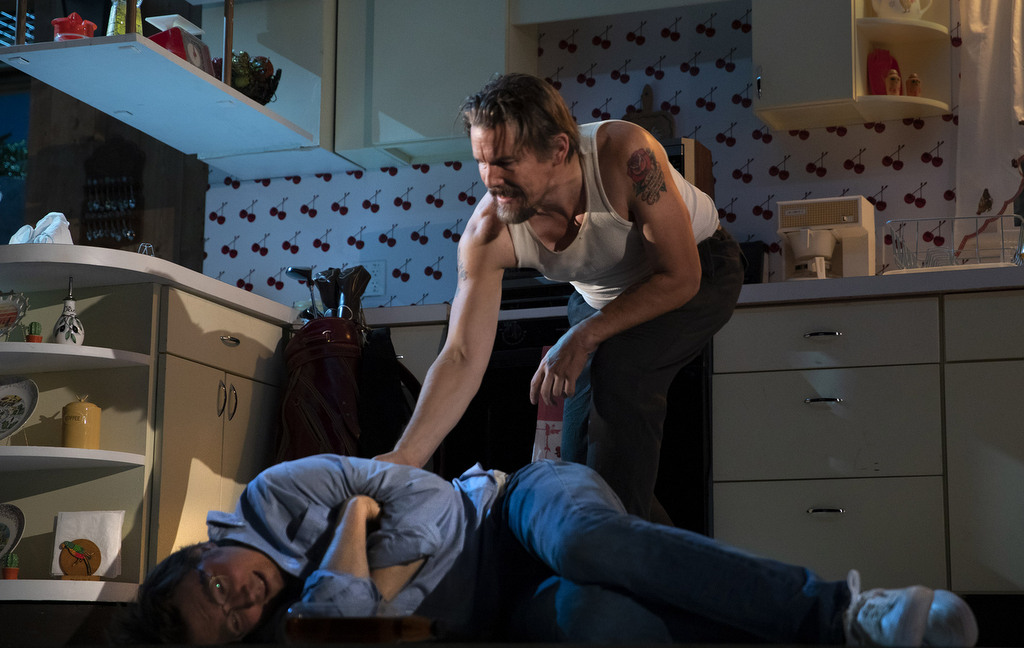

The arc of True West‘s development reveals Shepard’s acute examination of brothers Lee and Austin who wrangle and rage against each other to finally emerge from the emotional and familial folkways they’ve spun into their own self-fabricated prisons. The second act especially (the first act is more expositional and slower paced) screams with the taut, granular impact of subtly shifting, increasingly augmenting collisions of the mind, will and emotions of the older, social outcast and thief Lee (portrayed with dark tension, authenticity, humanity by Ethan Hawke) and the younger, ambitious, middle class Austin (the “mild-mannered” Dano seethes with fury and sub rosa angst that simmers to a boil). As these two attempt to reconnect after an estrangement, they thinly reconcile, negotiating confrontation and abrasion, while they attempt to deal with personal dissatisfaction. During their reunion, they discover that too far is never far enough to unleash the emotional convolutions, chaos and conundrums of their relationship.

(L to R): Ethan Hawke, Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

Of course, Shepard’s searing, dark humor and sardonic irony resides in Lee’s and Austin’s attempt to achieve an inner and outer expurgation. Interestingly, they use each other’s “being” as a battering ram against themselves and their complex, twisted “brotherhood.” And as they pummel and propel themselves “forward” through the charged, electrified atmosphere between them, they disintegrate their inner soul rot and misery. By the conclusion of the play, they have reached their own TRUE WEST. This is brilliantly symbolized and effected by Jane Cox’s Lighting Design, Mimi Lien’s Set Design and Bray Poor’s Original Music and Sound Design.

In the last moments between life, death and resurrection, Lee and Austin stand on the edge of a precipice eyeballing each other with uncertain respect and caution as they assess who they are and what they have wrought together. We realize that they have sought this desert of their creation. That they, by primal impulses, destroyed and trashed everything around them including some of their mother’s prized possessions to get there, is unfathomable to us. It is incomprehensible unless we examine our own self-destructive behaviors. However, their behavior is an achievement necessary to get to who they are. At the least they’ve shed pretense. They are raw creature/creations like the the yapping coyotes that lure pets, grab them and chow down for supper. However, where these characters go from this still point remains uncertain. But the hope is that it will result in a new identity for each, away from the annihilation and alienation of the parents who raised them.

Though Shepard’s play is set in the distant past, the themes and relationship that Hawke and Dano establish is vital, energetic, heart-breaking, mind-blowing, current. Each actor has brought so much of his own grist to Lee and Austin and responds with such familiarity and raw honesty to the other, it is absolutely breathtaking. It remains impossible not to watch both and be in awe of their craft. One is utterly engaged in the suspense of where the brothers’ impulses will take them as they scrape and claw at each other’s nerve endings to create bleeding wounds.

Ethan Hawke (standing) Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

Thanks go to James Macdonald’s direction and staging to facilitate Dano’s and Hawke’s memorable portrayals. With extraordinary performances like theirs, we are compelled to consider the characters, and determine how and why they are smashing each other’s personal boundaries to reveal inner resentments, hurts, and the chaotic forces that have swamped each of them in the most particular ways. The ties that bind them run so deep these two are oxymorons. They have identical twin souls, though they are externally antithetical. Why they clash is because they are like minded: raging, though controlled. Their emotions, like subterranean lava flows wait for the precise moment to explode and change the landscape around them. Lee is the more mature volcano; but his earthquakes create the chain reaction that stirs Austin’s. No smoke and mirrors here; just raw power.

As a perfect foil to spur the play’s development Gary Wilmes portrays Saul Kimmer, the producer hack who smarmes his way into Austin’s heart, then dumps him because he will not exact a devil’s bargain which Austin refuses to accept. Austin’s rejection of the “bargain,” enragese Lee. Wilmes is appropriately diffuse and opaque. Where does he really stand? What happened to make him turn on a dime regarding hiring Austin who has invested sweat equity and emotional integrity in a project Kimmer professed interest in? Wilmes is both authentic and the Hollywood “type,” to drive Lee and Austin against each other.

Likewise, as a foil, Marylouise Burke is LOL hysterical but frightening as their quirky mother. Her responses to their behavior are hyperbolic in the reverse and they speak volumes about how this family “functioned” in the past. She, too, helps to engine the suspense as Austin takes his power over Lee and she remains sanguine. All of the audience who are parents and especially those who have avoided the role are screaming silently in horror as the two “have at one another.” The situation and their confrontation is insane and humorous. Burke is perfect in the role as non-mediator. And Macdonald has done a magnificent job of balancing the tone and tenor of the last scene. As a result, Burke, Hawke, Dano deliver the lightening blow that helps us to realize the brothers’ intentions and the result of where they find themselves at the finale.

Ethan Hawke (standing) Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

So much of the production resides in these incredible portrayals, of Lee and Austin’s devolution into the abyss to come to an epiphany. Caught up with that, one may overlook the artistic design. But it is so integral for it reveals the family and reflects the dynamic interactions. Superb, for example are the sound effects which augment in intensity, the frame of lights contrasting the stage into darkness for set changes, the homely, well-ordered kitchen and alcove writing area, the lovely plants and their “growth” (a field-day for symbolists), and the props. The toasting scene is just fabulous. Kudos go to Mimi Lien (Set Design) Kaye Voyce (Costume Design) Jane Cox (Lighting Design) Bray Poor (Original Music & Sound Design) Tom Watson (Hair & Wig Design) Thomas Shall (Fight Choreographer).

Sam Shepard’s play is a powerful revelation of brotherly love and hate, its design and usefulness. At the heart of our global issues resides familial relationships. To what impact on the whole is the sum of its parts? To what extent do families foment their own hatred upon themselves and the culture to exacerbate the issues? Likewise, what of families who love each other? The interplay between families and society is present but understanding it remains elusive and opaque. Shepard attempts clarity. Certainly, Lee points out that family relationships are high stakes and sometimes the warring relatives kill each other. Certainly, Austin points out that he and Lee will not kill each other over a film script. But he underestimates how far he or Lee are willing to go. How far are any of us willing to go if pushed by a relative?

Life’s uncertainty, as in the best of plays is all about surprise and not knowing what will happen in the next moments. This production of True West lives onstage because the actors are immersed in the genius of acting uncertainty that is always present. Most probably, their performance is different daily because the actors have dared to breathe out the characters whose souls they have elicited. Just W.O.W! (wild, obstreperous, wonderful)

See True West before it closes on 17 March. It runs with one intermission at the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street between 7th and 8th. You can get tickets at their website HERE.