Blog Archives

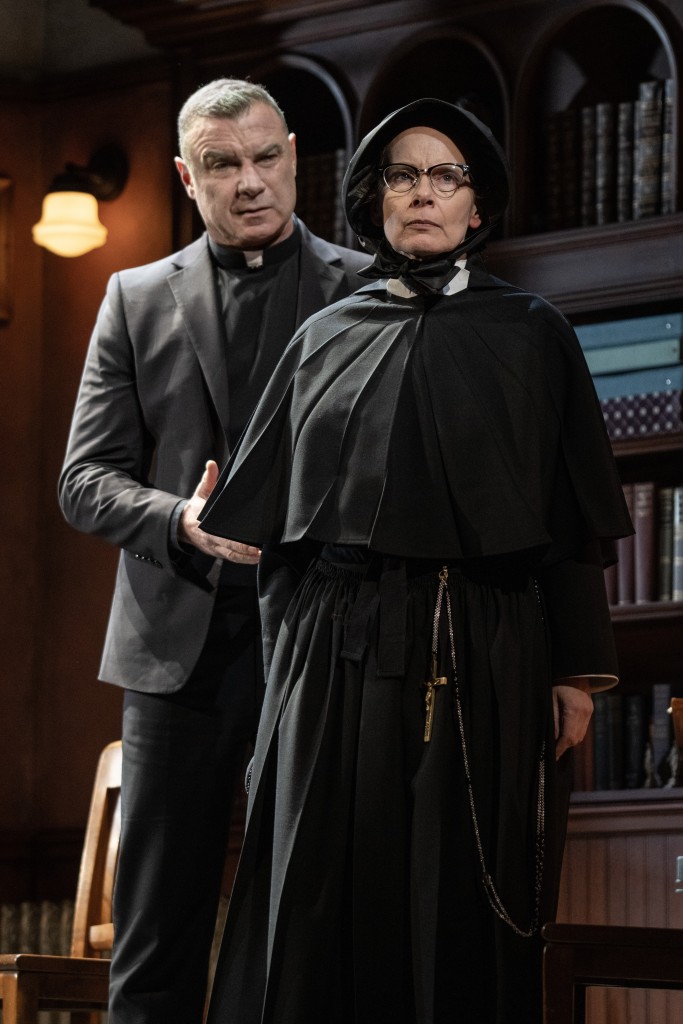

‘Doubt: a Parable’ The Revival With Liev Schreiber and Amy Ryan is Exceptional

If nothing is certain but uncertainty, then “doubt” is a natural state, as genius quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg in his uncertainty principle postulated. However, in the realm of faith, “doubt” may be a blasphemy as scripture encourages Christian adherents to “walk by faith, not by sight,” believing fervently, blindly in God and His truths. Such is the position that Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Amy Ryan) initially presents in John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: a Parable ably directed with specificity and edginess by Scott Ellis.

Doubt, currently in its first revival on Broadway since it premiered in 2005 continues to be a controversial powerhouse exposing embarrassing infelicities about the Catholic Church and the patriarchy.

In this beautifully acted revival running with no intermission at Todd Haimes Theatre, we note how the play emphasizes many of the divisive cultural issues at stake today though the setting is 1964, the Bronx, New York. However, Shanley nails the timeless sticky problems operating then and now with institutions that are incapable of policing themselves when they are run by men. Specifically, the play delves into church sponsored schools. Their male dominated hierarchy and paternalism shuffled off the harder tasks of teaching, learning and administration to the women. In this instance, the Sisters of Charity do the scut work in “collaboration” with the diocese in the fictional St. Nicholas Church.

To highlight his themes Shanley contrives a situation among three religious adherents who influence children toward or away from Catholic tenets. These include the charismatic Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber), pastor of St. Nicholas, the school principal, Sister Aloysius, and neophyte teacher and nunm Sister James (Zoe Kazan). Their dynamic interplay reveals age-old issues about the best and worst of human nature, goodness, egotism, arrogance, the need to control through guilt and fear, inability to discern lies from truth, gender inequality and hypocrisy.

Doubt opens with Schreiber’s Father Flynn addressing the audience as his congregation, preaching a sermon on the opportunities of having doubt as a part of the bonds of faith. Father Flynn’s sermon frames the play’s arc of development and the subject becomes the driving force as each character confronts their uncertainties about what is right, decent, truthful as they project their own inner weaknesses onto the behavior of each other. Importantly, their uncertainties reveal a crises of their faith in God to move them through the darkness. Instead of allowing God’s love to unify them, darkness, suspicion and doubt overcome them.

The second scene opens on the office finely outfitted by David Rockwell’s wood paneled set design on a turntable which later revolves to show a pleasant Garden and backdrop of the city beyond. Sister Aloysius unleashes her intentions and suspicions on Sister James in the confines of her principal’s office. Ryan’s Sister Aloysius is a martinet who runs a tight ship with a stern, icebox demeanor. In her spot-on, nuanced portrayal of the nun, Ryan never shines forth Christ’s light and love and remains largely an emotionless cipher until the conclusion. To her credit, Ryan never pushes Sister Aloysius’s austere attitude over the edge, but breathes feeling and life into her persuasiveness and her determination with fervency.

On the other hand, Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber) the priest, who is the pastor of St. Nicholas, manifests an openness, intelligence, flexibility, forward thinking personality and sense of irony. He and Sister Aloysius appear to be opposites in character, though both fabricate and lie; Father Flynn to drive home themes in his sermons, Sister Aloysius to “get at” the truth. The lighthearted, yet controlling Father conducts the physical education program and religion at the school. Both Sister Aloysius and Father Flynn follow the hierarchy and answer to the Monseigneur. This remains an obstacle for Sister Aloysius because she deems the elder cleric “other worldly” to a fault. She tells the young neophyte Sister James (Zoe Kazan), that he “doesn’t know who the president of the United States is.” Yet, here men rule.

A problem for the manipulative, coercive Sister Aloysius, the Monseigneur will dismiss any issue she brings to him, unlike another cleric she confided in at St. Boniface who believed her word and got rid of a priest Sister Aloysius implies was a pederast. Suspicious about Father Flynn, and questioning the personal purpose of his sermon about “doubt,” Sister Aloysius picks at Sister James like a feather pecking chicken who dominates hens by pecking them to draw blood because she enjoys its taste.

Preparing her victim for maximum influence, Aloysius criticizes Kazan’s Sister James. She derides her showboating as a teacher, her enthusiasm about her subject, her kindness to the students. She discourages Sister James’ relaxed atmosphere in her classes. After reducing the young nun to tears, she directs the neophyte to be emotionless and watchful about anything untoward. We learn later, as Sister James confides in Father Flynn, that the older nun has stolen her joy about teaching and has contributed to her bad dreams and loss of peace. This irony is not lost on us today, when religion is used as a hammer and sickle to browbeat and slice up the condemned populace to contort their lifestyles to politicized religious tenets popular over 120 years ago.

Sister James becomes the perfect foil for the imperious, commanding Sister Aloysius to manipulate and play upon in the tug of war between Sister Aloysius and Father Flynn. Initially, the “war” appears grounded in a difference in philosophies and life approaches between progressivism vs. conservatism. However, the divisiveness between them takes a sinister turn and explodes as Sister Aloysius gives rise to her suspicions that Father Flynn is grooming Black student Donald Muller for pederasty by giving him alcohol in the sacristy. It is an accusation that is proven only in her imagination.

Sister James is like a deflated ball tossed about in the storm that rages between Sister Aloysius’s determination to expose and evict Father Flynn from the church and Father Flynn’s insistence he is telling the truth and has done nothing wrong. In a climactic scene between them, Flynn’s denials and pleadings with her to count the cost to Donald, him and herself and to amend her convictions and threats because of a lack of proof, go on deaf ears. She has converted herself into the “anointed.” She would make those of the Inquisition proud, except they never would listen to a female.

To complicate the matter Sister Aloysius meets with the Black child’s mother, Mrs. Muller (the superb Quincy Tyler Bernstine). Mrs. Muller expresses that she is thankful Father Flynn has become her child’s protector. If Donald stayed in his previous school, he “would have been killed” by the bullies. Sister Aloysius dismisses Mrs. Muller’s backstory about her son’s beatings by his father for “being that way.” Instead, the principal is self-righteous and gratified that her determination has led to Donald Muller’s being dismissed from the Altar Boys, which Mrs. Muller explains devastated Donald.

Mrs. Muller leaves with the assurance that Donald will be able to finish out the few months left, but Sister Aloysius is not satisfied and won’t be satisfied until Father Flynn has been exposed and kicked out of the priesthood. Because she is the assiduous hunter of her prey, Father Flynn, we become sympathetic to his cause and Sister James’ acceptance that he is innocent of Sister Aloysius’ allegations. However, the Catholic Church since 2000 has been expelling priests for pederasty and has paid great sums of money in damages to men who testified years later to being abused by priests’ sexual predation.

So, Father Flynn may be a pederast and Sister Aloysius may be correct in her “gut instinct” that he is a predator. Enter Werner Heisenberg. Uncertainty reigns without proof and admission of guilt and an act of contrition and repentance which Schreiber’s stalwart, assertive Father Flynn will never yield up.

The performances and direction are uniformly terrific as is Ellis’ pacing and vision which leaves the audience in a breathtaking conclusion and Sister Aloysius upended and overturned in her philosophy and life approach. Thanks to Linda Cho’s appropriate costume design, Kenneth Posner’s lighting design and Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design, and Charles G. LaPointe’s hair & wig design, Doubt resonates with currency. As mentioned before, David Rockwell’s scenic design, first with a gorgeous cathedral interior setting for St. Nicholas, then with its turntable sets is appropriate for a place of peace which, by contrast, echoes with torment, division and fear.

The complexity of suspicion, accusation and innocence remind us of our time, and of the insistence of liars to demand they are right on little proof when the stakes are high. In the play’s instance careers may be upended, reputations are at stake, and individuals are harmed for the sake of one’s suspicions of imagination. Today, it is no less shattering that lies are the pylons which shore up candidacies to achieve power by any means necessary, even if it means the destruction of nations, citizens, the government. In its timeless themes about assessing truth when the professing upright religious protect liars, fantasists and themselves from accountability, Doubt is a profound must-see.

Doubt. Todd Haimes Theater, 42nd St between 7th and 8th with no intermission until April 21st. roundabouttheatre.org.

‘Caroline or Change’ the Roundabout Theatre Company Revival, Starring Sharon D Clarke

“Sixteen feet below sea level, torn tween the Devil and the muddy brown sea,” Caroline (the terrific Sharon D Clarke) characterizes her existence to herself in the musical revival Caroline, or Change at Studio 54. At the outset Caroline is in the basement doing the laundry for the Gellmans accompanied by the rhythms of The Washing Machine (Arica Jackson) and The Radio singers #1, #2, #3 (Nasia Thomas, NYA, Harper Miles). They are anthropomorphic representations of Caroline, along with The Dryer (Kevin S. McAllister) who makes the atmosphere as “hot as hell.”

Tony Kushner’s book and lyrics and Jeanine Tesori’s music bring to life a portrait of a black maid’s inner hell. She has no prospects of betterment to uplift herself out of the symbolic, oppressive swamps of white supremacist Lake Charles, Louisiana, 1963. Embittered, miserable, impoverished, on a minimum wage to support herself and three kids, she has lost hope waiting for goodness to come. She resents everyone, most of all “Caroline” who has created the situation she finds herself in, abandoned by her husband, single, a drudge at thirty-nine-years old.

While other blacks in the South become involved with the Civil Rights Movement and march against the brutality of Jim Crow, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, or seek an education, the exhausted Caroline can barely suffer herself through the next day’s labors cleaning and watching over the Gellman’s son, eight-year-old Noah (Jaden Myles Waldman the evening I saw it) who mourns his recently deceased mother. Her employers, Stuart Gellman (John Cariani) and Rose, his second wife (Caissie Levy) who attempts to be nice to Caroline, only make the situation worse.

Victims themselves of institutional racism, caught up in the discriminatory animus of the South, they can’t afford to raise Caroline’s wages. Nor do they relate to her on a personal level to uplift her, not that she would accept their attempts.

Indeed, throughout the play Caroline’s soul is metaphorically buried alive and/or drowning underwater as she struggles to pay for rent and food for herself and her children, one of whom is in Viet Nam. It is clear no one is coming to dig her out or rescue her, least of all herself. Unless a catalyst stirs her to resurrection, she will continue until the anger breaks out in violence against others; or she turns to self-destruction (acutely represented in a scene with Rose at the show’s turning point).

Interestingly, this horror of racism and its witting/unwitting adherents to a system that destroys is only made watchable through Tesori’s music, and Kushner’s poetic lyrics. Caroline’s anger and self-hatred projected out onto everyone, including friend Dotty Moffett (Tamike Lawrence) could have been a one-note agony of oppression and bondage. Key themes would have been undermined and occluded without the symbolism and majesty of the music and the fabulous voices that weave out Caroline’s story, of her inability to hope in an era when hope was the watchword of the Black South.

Tesori’s vibrant mix of 1950s-60s R & B/pop/soul/jazz/klezmer with a Diana Ross and The Supreme’s number at the finale and Kushner’s lyrics throughout measure like a soaring opera. They elevate the character of Caroline into an epic hero with her attendants, The Moon (the lovely voiced N’Kenge) and her children, especially Emmie (Samantha Williams) who has the spunk and courage to envision more for herself. Without our learning about Caroline’s emotional devastation embodied by the sonorous, operatic voices, Caroline or Change would have lost its vitality, currency and great moment, all of which are timeless and relatable to America 2021.

The superb cast is up for the challenge, singing beautifully, powerfully. Initially, it took me a while to understand the lyrics; the performers’ articulation wasn’t as acute as needed. However, like getting used to Shakespearean language, the heightened bond between the cast and the audience conveyed the centrality of Caroline’s conflicts. These become “a matter of ethics,” pride and dignity for her as a black woman who must carve out her identity in a bludgeoning, challenging racist society. What Kushner fashions as an issue of nickels and dimes evolves into the crux of black economic experience in the U.S, then and now.

Caroline’s dilemma is whether or not to take the change left in Noah’s pants pockets that he forgets to remove before Caroline does the laundry. Rose tells her to take it as a lesson for Noah to learn to “mind his money.” Caroline desperately needs the small bit of change, but also needs her soul to be intact. The minuscule handout becomes a symbolic gesture of Noah’s grandiose charity (in his view he believes Caroline and family appreciate his “largesse”). From Caroline’s perspective it symbolizes belittling crumbs of corruption taken from a “child,” making her an indigent, a beggar who cannot “rise above.” When she submits to temptation out of want for her children, she drains her dignity and faith in herself to “make it on her own,”

Of course, there would be no problem if the emotionally challenged Gellmans just provided a living wage instead of using money as a perverse lure for Caroline to damn herself. Caroline’s conflict symbolically parallels the perniciousness of economic inequality in America. It recalls demeaning public assistance handouts. Instead, if corporations paid the proportionate taxation rates, and with employers provided a decent, living wage, poverty, misery and an unequal justice system could be eradicated. However, the the US with its notorious history of enslavement (both white, black and colored) needs to demean souls to feed its own psychic sickness and keep the washing machine laboring by the underclasses to cleanse itself from its deranged filth.

This is just one of the themes Kushner reveals in a production luxurious with ironies and messages. Another controversy to look for is the dynamic between the Gellman’s situation and Caroline’s. The Gellmans are Jews who, too, experience discrimination and abuse as outsiders from the white supremacists that dominate the surrounding culture not only in the South but indeed, everywhere. Yet, there is little real empathy or understanding between Caroline and the Gellmans.

This humorously comes to the fore during the Chanukah celebration. Rose’s father, Mr. Stopnick (Chip Zien masterfully steals the moment) a Jew from New York City rails against Southern racism and hypocrisy. He uplifts the blacks’ position to foment violent revolution, which he suggests should have happened with the US Communist Party in the 1930s. Of course he is shushed up.

Meanwhile, his attitude about money which he delivers in a Marxist speech to Noah as he gives him Chanukah gelt is ironic. The twenty dollars ends up in Caroline’s “change cup.” Noah and she argue and afterward, Caroline realizes the fullness of the compromised, hateful individual she’s allowed herself to become. Sharon D. Clarke’s aria ‘Lot’s Wife’ is a showstopper. In the song Caroline’s conflict spills out in an epiphany. She concludes with a prayer to God, “Set me free; don’t let my sorrow make evil of me.”

Michael Longhurst’s direction of the ensemble is excellently dotted with interesting choices. The revolving platform is used symbolically. For example, during the Chanukah Party, Caroline, Dotty and daughter Emmie go in circles to please the Gellmans. Kudos enlightened staging by Fly Davis (set and costume design). Yet Caroline, et. al control; their servitude defines their strength. Without them, the Gellmans would be “on their own,” incapable, unable, weak. We are reminded of the South’s “need” of slavery rather than building a strong foundation from their own or paid labor which would have stultified their laziness and greed and encouraged a more prosperous economy and no need for a Civil War to end slavery, that peculiar “Christian” institution.

Kudos to the creative team: Jack Knowles (lighting) Paul Arditti (sound) Amanda Miller (hair and wigs) Sarah Cimino (make-up) Joseph Joubert (music direction) Nigel Lilley (music supervision) Ann Lee (choreography) who express Kushner’s themes roundly and provide a glistening backdrop (the swampland surrounding the house is wonderful) for the cast to play upon.

Caroline or Change opened in 2003 at The Public Theatre to mixed reviews, though it garnered awards. Sharon D Clarke starred as Caroline and won an Olivier for it in the London production in 2017. In the Roundabout production she reaffirms her grandeur, infusing her portrayal with substance, hitting her emotional peaks and turns with a resonant, anointed voice. This is one to see for the cast’s performances. If you missed it in 2003, don’t miss it in 2021. It is a reminder of what was and what is and a hope of what might be if we leave off divisive hatreds and rebirth ourselves to a better way. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2021-2022-season/caroline-or-change/

‘The Rose Tattoo,’ Marisa Tomei Is Tennessee Williams’ Fiery, Sensual Serafina, in a Stellar Performance

Marisa Tomei in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Atmosphere, heat, the heavy scent of roses, candles, mysticism, undulating waves, torpid rhythms, steamy melodies, fantastical rows of pink flamingos, a resonant altar of the Catholic Madonna. These elements combine to form the symbolic backdrop and evocative wistful earthiness that characterize Roundabout Theatre Company’s The Rose Tattoo at American Airlines Theatre.

Tennessee Williams playful, emotionally effusive tragic-comic love story written as a nod to Williams own Sicilian lover Frank Merlo, is in its third revival on Broadway in a limited engagement until 8th December (the Catholic date of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception). Reflecting upon Marisa Tomei’s portrayal of Serafina in The Rose Tattoo, this is an ironic, humorous conclusion in keeping with the evolution of her character which Tomei embraces as she exudes verve, sensuality, fury, heartbreak and breathtaking, joyful authenticity in the part.

If any role was made for Tomei, divinity and Tennessee Williams have placed it in her lap and she has run with it broadening the character Serafina Delle Rosa with astute sensitivity and intuition. Tomei pulls out all the stops growing her character’s nuanced insight. She slips into Serafina’s sensual skin and leaps into her expanding emotional range as she morphs in the first act from grandiose and joyful boastfulness to gut-wrenching impassioned sorrow and in the second act to ferocity, an explosion of suppressed sexual desire and its release. All of these hot points she elucidates with a fluidity of movement, hands, limbs, head tosses, eye rolls which express Serafina’s wanton luxury of indulgent feeling and effervescent life.

The contradictions of Serafina’s character move toward a hyperbolic excess of extremes. When speaking of her husband Rosario and their relationship, their bed is a sanctum of religion where they express their torpid love each night. She effuses to Assunta (the excellent Carolyn Mignini) how she mysteriously felt the conception of her second child the moment it happened. A rose tattoo like the one her husband Rosario wore on his chest appeared like religious stigmata without the dripping blood. And it burned over her heart, a heavenly sign, like others she receives as she talks to the statue of the Madonna, and remains a worshipful adherent to Mother Mary, praying and receiving the anointed wisdom whenever necessary.

Marisa Tomei, Emun Elliott in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Rosario’s family is that of a “baron,” though Sicily is the “low” country of Italy and an area fogged over with undesirables, thieves and questionable heritages as the crossroads of Europe. We know this “baron-baroness” is an uppity exaggeration from the looks on the faces of her gossipy neighbors and particularly La Strega (translated as witch) who is scrawny, crone-like and insulting. Constance Shulman is convincing as the conveyor of Ill Malocchio-the evil eye. Her presence manifests the bad-luck wind that Assunta refers to at the top of the play and to which Serafina superstitiously attributes the wicked event that upends her life forever.

Williams’s characterization of Serafina is brilliant and complex. Director Trip Cullman and Tomei have effected her intriguing possibilities and deep yearnings beyond the stereotypical Italian barefoot and pregnant woman of virginal morals like Our Lady. It is obvious that Tomei has considered the contradictions, the restraints of Serafina’s culture and her neighbors as well as her potential to be a maverick who will break through the chains and bondages of her religion and old world folkways after her eyes are opened.

We are proud that Serafina disdains the gossiping neighbors with the exception of Assunta and perhaps her priest. Though Serafina’s world does not extend beyond her home, the environs of the beach, her daughter Rosa (Ella Rubin) and Rosario, a truck driver who transports illegal drugs under his produce, she is a fine seamstress. And in her business interactions with her neighbors and acquaintances, we note that she has money, is industrious, resourceful and a canny negotiator.

It makes sense that Rosario (whom we never see because he is a fantasy-Williams point out) treats her like a baroness filling their home with roses at various times to reassure her of her grandness. And the poetic symbol of the rose as a sign of their love and the romance of their relationship is an endearing touch, reminiscent of the rose tattoo on his chest signifying his commitment to her. At the outset of the play, a rose is in Serafina’s hair which she wears waiting for Rosario to come home. As she does, we believe she is fulfilled in their love and the happy status of their lives in a home on the shores of paradise, the Gulf Coast of Mississippi.

What is not manifest and what lurks beneath becomes the revelation that all is not well, that her Rosario is not real, but is an illusion. Typical of Williams’ work are the undercurrents, the sub rosa meanings. The rose is also a symbol of martyrdom, Christ’s martyrdom. And it is this martyrdom that Serafina must endure when word comes back that Rosario has been killed, burned in a fiery crash which warrants his body be cremated. Unfortunately, the miraculous son of the burning rose on her chest that appeared and disappeared, she aborted caused by the extreme trauma of Rosario’s death.

Marisa Tomei, Emun Elliott in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

The rose as Williams’ choice symbol is superbly complex. For Rosario’s rose tattoo also represents his amorous lust for women, one of whom is Estelle Hohengarten (Tina Benko) who asks Serafina to make a gorgeous, rose-colored silk shirt for “her man.” When Estelle steals Rosario’s picture behind Serafina’s back, we know that Rosario led a double life and we are annoyed at Estelle’s arrogance and presumption to ask his wife to make such a gift shirt. But in William’s depth of characterization for Estelle, most probably Rosario is also philandering on Estelle who, to try to keep him close, gives him expensive gifts like hand-made silk shirts.

Williams clues us in that her faith and passion for Rosario has blinded her judgment and overcome her sharp intellect and wisdom. In fact it is an idolatry. Her religion stipulates that no human being should be worshiped or sacrificed for. Serafina’s excessive personality has doomed her to tragedy, betrayal and duplicity with Rosario. Ironically, his death is her freedom, but she must suffer his and her son’s loss ,a burden almost too great to bear, even for one as strong as Serafina who does become distracted, unkempt and uninterested in life.

Because Rosario, the wild rose with thorns is not worthy of Serafina’s love, after his death there is only pity for the cuckholded Serafina and a finality to her exuberant life until the truth of who Rosario really was lifts her into a healthy reality. Tomei’s breakdown is striking and Williams creates the tension that in weeping for the “love” of her life who indeed has betrayed her, she will be wasting herself. He also affirms the huge gulf between her ability to live again and her lugubrious state which continues for three years as she mourns an illusion.

The question remains. Will she come to the end of herself? The romantic fantasy held together with the glue of her faith and the enforced, manic chastity of her old world Italian mores must be vanquished. But how? It is in the form of the charismatic and humorous Alvaro Mangiacavallo. But until then Serafina withers. Isolating herself, she implodes with regret, doubt, sorrow and dolorous grief, as well as anger at her daughter Rosa who wants to live and find her own love like her mother’s.

The mother-daughter tensions are realistically expressed as are the scenes between Tomei and Jack (Burke Swanson) Rosa’s boyfriend, which are humorous. Altogether, the second act is brighter; it is companionable comedy to the tragedy of the first act.

When she meets Alvaro, in spite of herself, she responds with her whole being to his attractiveness. As they become acquainted, she accepts his interest in her for what she may represent; a new beginning in his life. It is a new beginning that he tries to thread into her life to resurrect her sexual passions and emotions of love. Thus, he pulls out all the stops for this opportunity to win her, even having a rose tattooed upon his chest in the hope of taking Rosario’s place in her heart.

Marisa Tomei, Emun Elliott in ‘The Rose Tattoo,’ by Tennessee Williams, presented by Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Emun Elliott is spectacular as the clownish, emotionally appealing, lovable suitor who sees Serafina’s worth and beauty and attempts to endear himself to her with the tattoo. Along with Serafina’s discovering Rosario’s betrayal, Elliott’s portrayal of Alvaro solidifies and justifies why Serafina jumps at the opportunity to be with him. He is cute. He is real. He is as emotional and simpatico as she is. He is Sicilian and above all, he is available and interested in her. It is not only his steamy body that reminds her of Rosario’s, but she is attracted to his humor, sensibility and sensitivity of feeling which mirrors hers.

After discovering Rosario’s duplicity, understanding Alvaro’s concern and care for three women dependents and his honesty in admitting he is a buffoon disarms Serafina. Alvaro’s strength and lack of ego in commenting that his father was considered the village idiot is an important revelation for her as well. Indeed, as she views who he is, she senses that his humility and humorous self-effacement is worth more than all of Rosario’s boastfulness that he was a baron which he wasn’t.

As the truth enlightens her, Tomei’s Serafina evolves and sheds the displacement and her sense of confusion and loss which was also a loss of her own imagined “secure” identity as Rosario’s “wife.” Wife, indeed! Rosario’s mendacity made her into a cuckhold and a brokenhearted fool over a man who was not real. At least Alvaro is real. The comparison between the men reinforced with Rosario’s unfaithfulness, which she can now admit to herself, prompts her to reject the religion that kept her blinded and the antiquated mores that made her a fool and kept her alone and in darkness.

Shepherded by Cullman, Elliott and Tomei create an uproarious, lively and fun interplay between these two characters who belong together, like “two peas in a pod” and have only to realize it, which, of course, Alvaro does before Serafina. Tomei’s and Elliott’s scenes together soar, strike sparks of passion and move with the speed of light. The comedy arises from spot-on authenticity. The symbolic poetry, the shattering of the urn, the ashes disappearing, the light rising on the ocean waves (I loved this background projection) shine a new day. All represent elements of hope and joy and a realistic sense of believing, grounded in truth for both protagonists.

Tomei, Elliott, Cullman and the ensemble have resurrected Williams’ The Rose Tattoo keeping the themes current and the timeless elements real. Duplicity, lies, unfaithfulness, love and the freedom to unshackle oneself from destructive folkways that lead one into darkness and away from light and love are paramount themes in this production. And they especially resonate for our time.

I can’t recommend this production enough for its memorable, indelible performances especially by Elliott and Tomei shepherded with sensitivity by Cullman. The evocativeness and beauty of the staging, design elements and music add to the thematic understanding of Williams’ work and characters. Kudos goes to the creative team: Mark Wendland (set design) Clint Ramos (costume design) Ben Stanton (lighting design) Lucy Mackinnon (projection design) Tom Watson (hair and wig design) Joe Dulude II (make-up design). Bravo to Fiz Patton for the lovely original music & sound design.

The Rose Tattoo runs with one intermission at American Airlines Theatre (42nd between 7th and 8th) until 8th December. Don’t miss it. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Toni Stone,’ A Baseball Great Takes Center Stage at the Roundabout

April Matthis in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘Toni Stone,’ directed by Pam MacKinnon, written by Lydia R. Diamond (Joan Marcus)

Imagine being so excellent at baseball you have to join a boys’ team because no one on the girls’ team can hold a candle to you! Toni Stone was the first African American female to distinguish herself and play pro ball ball in the Negro Leagues. No other woman of any race topped her skill, pluck or stamina in 1953, not that any women even conceived that they should try. Based on the biography Curveball, The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone by Martha Ackmann, Roundabout’s humorous, intriguing and illuminating production about baseball, race, gender, inspiration and ambition, Toni Stone, written by Lydia R. Diamond, is currently at the Laura Pels Theatre until the 11th of August.

Starring Obie Award Winner April Matthis, who transforms herself into the feisty, wise-cracking, straight-talking, female baseball maverick in the two act production that runs with one intermission, we learn Toni’s inside perspective about what it was like to break into the prestigious negro leagues. She was the only woman to do exploits with her male teammates playing the game she adored and gave the best years of her life to in the late 1940s to 1954. Hired to play second base with The Clowns in 1953, Toni Stone took over the position that Hank Aaron had played the previous year and rocked it in 50 outings, slamming a hit off the legendary pitcher Satchel Paige. Matthis as Stone is incredible, moment-to-moment, real.

(L to R): Harvy Blanks, Jonathan Burke, Daniel J. Bryant, Ezra Knight, Toney Goins, Eric Berryman, Phillip James Brannon, April Matthis, Kenn E. Head in ‘Toni Stone,’ Roundabout Theatre Company, written by Lydia R. Diamond, based on the book ‘Curveball, The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone,’ by Martha Ackmann directed by, Pam MacKinnon (Joan Marcus)

The structure of Toni Stone is picaresque and dramatic. It spans the years from the 1920s to the 1950s in various locations around the country. With superb, athleticism by the actors, the movements are precision, characteristically baseball as the actors represent the players on Toni’s exhibition team The Clowns (like the Harlem Globetrotters in the basketball world today). The Choreography by Camille A. Brown in Act I is taut as we watch the players practice their fielding, throwing, catching, swinging as professional ball players with the fierce pride and confidence to match any professional today. They and Brown’s choreography are impressive. Director Pam MacKinnon’s staging segues from bit to bit with fast paced spin in the first act, and less precision in the second act which becomes more ponderous.

The Lighting (Allen Lee Hughes) and Set Design (Riccardo Hernandez) echoe where Tony strived to spend the best years of her life, on the ball field, with lights blaring down (at the right moment) and with bleachers for the full effect and accoutrements, i.e. uniforms (Dede Ayite) caps, gloves, bats minus the ball which is held in mime invisibly as the players “throw” and “catch.” The minimalism is effective in lifting the subject of what has been described as the only true American sport. The lack of extraneous spectacle draws our attention to the dialogue between and among the players and other characters. Without the razzle dazzle, we focus on Toni Stone’s narration during which she confides to us about salient details of her life and events which reveal the themes of the production: steadfastly overcoming the odds, ambition as everything, female success in a man’s world, and effort and hard work pays off if one keeps focused.

(L to R): Eric Berryman, Jonathan Burke, April Matthis, Daniel J. Bryant, Ezra Knight, ‘Toni Stone,’ written by Lydia R. Diamond, directed by Pam MacKinnon, based on the book ‘Curveball, The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone,’ by Martha Ackmann (Joan Marcus)

April Matthis has the accent, the drawl, the humor to evoke Toni’s persona and let us in on the secrets of her baseball obsession and efforts to be the best. She’s not as good as Jackie Robinson whom the players reference moving from the Negro Leagues in a leap over the line of segregation to Major League baseball as the first African American to integrate the Majors. Nevertheless, Toni was a one-of-a-kind celebrity and superb ball player. It is that particularity that playwright Diamond characterizes and Pat MacKinnon highlights through her direction so that it explodes on stage and holds our interest.

The top of the play begins with her teammates on the Indianapolis Clowns who introduce her and then she introduces them with humorous quips and prods. As the men move like poetry as they practice behind her, Toni gives an overview of the game with a rhythm all her own in description and enumeration of details. Her full on discussion of the ball, likening it to that which is a part of her hand and which she balances by its weight, shape and feel is typically mind-bending. It indicates how one can be engrossed by that which one loves to go very deep! Indeed, she remarks that as the girls in high school were obsessed about boys, she could only see, hear and think about baseball. A fiend she spends her waking moments on the baseball fields of St. Paul where her tom boyishness and fervor were accepted by the guys who “let” her play with them.

(L to R): Jonathan Burke, Harvy Blanks, Toney Goins, Kenn E. Head, April Matthis, Eric Berryman, Daniel J. Bryant, Phillip James Brannon, Ezra Knight, ‘Toni Stone,’ written by Lydia R. Diamond, directed by Pam MacKinnon, Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

However, when she did break into pro baseball, the players gave her “what for.” Some of the intriguing elements of the production occur when Toni hones in on confronting difficulties. She prides herself on “taking it” i.e. the male-on-female abuse. She kept a stoic outlook and sustained the bruising and battering she got when the players treated her like a guy, but more so. In one segment, her friend, prostitute Millie (an exceptional Kenn E. Head) is with her as she applies cream on a bruise she receives from a player out to “get her.” In that brief moment is the tip of the iceberg of what she went through as the singular woman among the burly, smelly, macho men. Yet, she felt that she was one of them but through the years many of them treated her as “the other.” Indeed, she wasn’t allowed in the locker room and had to change in spaces they had to find for her as they traveled on the road.

Playing on the Negro Leagues, the players encountered the usual “hospitality” of the Jim Crow South; they were banned from white hotels, motels and bathrooms and subjected to racist, discriminatory abuse. In one town the only hotel they were accepted in was one that catered to sex workers. This is the place where she meets Millie, replete with flowery robes courtesy of Dede Ayite’s Costume Design, albeit Head wears them over his Clowns’ uniform. The interactions between Kenn E. Head’s Millie (his feminine gestures are humorous, but real) and Matthis’ Toni are poignant and revelatory. Head particularly has superb timing with his looks, his one-liners.

(L to R): ,Toney Goins, April Matthis, Kenn E. Head, in ‘Toni Stone,’written by Lydia R. Diamond, directed by Pam MacKinnon, based on the book ‘Curveball, The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone’ by Martha Ackmann, Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

There are sensitive illustrious moments drawn between the two, for example when Millie gives her tips on how to do her hair. And as Toni questions Millie for her wisdom regarding men, we note that her attitude is unrelenting and strong. We never see her break down even with Millie; she can’t afford that luxury. And very simply, it is not the “Toni Stone” style.

In another segment the playwright examines Toni’s relationships, in particular Alberga (portrayed by the superb, likable Harvy Blanks) who she allows to buy her drinks in a bar. How these scenes are simplistically staged using two players to hold a board is part of the fun. It is obvious that Alberga intends to sweet-talk her and ply her with alcohol which doesn’t understand until Millie explains it to her. Eventually, Toni abruptly calls him down on it and distracts him by talking “baseball.” Taken aback by her honesty and unpretentious, unfeminine, unflirty demeanor, they continue to “hang out” whenever she is in town.

Toni decides to marry him; it is the right time. When he and she are tired of smelling the man-sweat wreak of her own exertions on her clothes, coupled with sweaty, noxious odors of her male baseball counterparts, it is one more element that helps her decide to leave baseball. The last straw occurs after she is traded to the Kansas City Monarchs and benched most of the time sitting next to teammates whose dislike for her is obvious. Toni Stone leaves for a civilian life with her husband and never returns to baseball again.

Perhaps the most searing effect of this production is in how the playwright weaves in the details of the history of our nation’s racism during the accounts of her life on the field and in pro baseball. These thread everpresently throughout. In one instance Toni editorializes about the discrimination and it is here where the director and choreographer work their magic, starkly in a memorable finality to Act I. Toni stares out at the audience and comments about the “spectacle” of exhibition games where they were to make the audience laugh. The players “dance” behind her as grinning “clowns,” though one imagines that each and every one of the players is “crying inside.”

The depth and beauty of the sport she loves is compromised by the stereotypical, racial attitudes. The indictment is clear as Matthis’Toni stares out at the audience. We are a throwback to the historical audience who wanted the “negroes” to entertain them. It is then, the playwright infers little has changed regarding discriminatory racial stereotypes and bigoted acts. The tragedy of this is the stereotype obviates the profound depth of what African Americans/blacks were/are but are locked out from “becoming.” It is a vital moment in the play and the perfect end of the first act. The second act does not end as strongly.

Kudos to the creative team not already mentioned: Broken Chord (Original Music & Sound Design) Cookie Jordan (Hair & Wig Designer) Thomas Schall (Fight Director).

Toni Stone runs with one intermission at the Laura Pels Theatre, the Harold and Miriam STeinberg Center for Theatre on 46th Street between 6th and 7 Avenue until the 11th of August. For tickets and times go to the Roundabout Website by CLICKING HERE.

The Mindblasting Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano Cave to Primal Hatreds and Private Desolations in Sam Shepard’s ‘True West’

(L to R): Ethan Hawke, Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

True West by Sam Shepard is a tour de force which easily reveals actors’ talents or their infelicities. Indeed, it may be a devastating on-stage nightmare if the actors’ skills do not resonate with a fluid “moment-to-moment” dynamic that sits precariously on the knife-edge of emotional chaos and crisis. This is especially so in Act II of Shepard’s True West which is currently in revival at the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street, starring the consummate Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano. Both actors rise to the pinnacle of their skills surfing their own moment-to-moment impulses in this sense-memory tearing, emotional slug-fest of a play about siblings. This is a glorious, shattering production thanks to Hawke and Dano who once more prove to be among the great actors of their generation. If Shepard is apprised of this production in another realm of consciousness, surely he is thrilled.

The arc of True West‘s development reveals Shepard’s acute examination of brothers Lee and Austin who wrangle and rage against each other to finally emerge from the emotional and familial folkways they’ve spun into their own self-fabricated prisons. The second act especially (the first act is more expositional and slower paced) screams with the taut, granular impact of subtly shifting, increasingly augmenting collisions of the mind, will and emotions of the older, social outcast and thief Lee (portrayed with dark tension, authenticity, humanity by Ethan Hawke) and the younger, ambitious, middle class Austin (the “mild-mannered” Dano seethes with fury and sub rosa angst that simmers to a boil). As these two attempt to reconnect after an estrangement, they thinly reconcile, negotiating confrontation and abrasion, while they attempt to deal with personal dissatisfaction. During their reunion, they discover that too far is never far enough to unleash the emotional convolutions, chaos and conundrums of their relationship.

(L to R): Ethan Hawke, Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

Of course, Shepard’s searing, dark humor and sardonic irony resides in Lee’s and Austin’s attempt to achieve an inner and outer expurgation. Interestingly, they use each other’s “being” as a battering ram against themselves and their complex, twisted “brotherhood.” And as they pummel and propel themselves “forward” through the charged, electrified atmosphere between them, they disintegrate their inner soul rot and misery. By the conclusion of the play, they have reached their own TRUE WEST. This is brilliantly symbolized and effected by Jane Cox’s Lighting Design, Mimi Lien’s Set Design and Bray Poor’s Original Music and Sound Design.

In the last moments between life, death and resurrection, Lee and Austin stand on the edge of a precipice eyeballing each other with uncertain respect and caution as they assess who they are and what they have wrought together. We realize that they have sought this desert of their creation. That they, by primal impulses, destroyed and trashed everything around them including some of their mother’s prized possessions to get there, is unfathomable to us. It is incomprehensible unless we examine our own self-destructive behaviors. However, their behavior is an achievement necessary to get to who they are. At the least they’ve shed pretense. They are raw creature/creations like the the yapping coyotes that lure pets, grab them and chow down for supper. However, where these characters go from this still point remains uncertain. But the hope is that it will result in a new identity for each, away from the annihilation and alienation of the parents who raised them.

Though Shepard’s play is set in the distant past, the themes and relationship that Hawke and Dano establish is vital, energetic, heart-breaking, mind-blowing, current. Each actor has brought so much of his own grist to Lee and Austin and responds with such familiarity and raw honesty to the other, it is absolutely breathtaking. It remains impossible not to watch both and be in awe of their craft. One is utterly engaged in the suspense of where the brothers’ impulses will take them as they scrape and claw at each other’s nerve endings to create bleeding wounds.

Ethan Hawke (standing) Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

Thanks go to James Macdonald’s direction and staging to facilitate Dano’s and Hawke’s memorable portrayals. With extraordinary performances like theirs, we are compelled to consider the characters, and determine how and why they are smashing each other’s personal boundaries to reveal inner resentments, hurts, and the chaotic forces that have swamped each of them in the most particular ways. The ties that bind them run so deep these two are oxymorons. They have identical twin souls, though they are externally antithetical. Why they clash is because they are like minded: raging, though controlled. Their emotions, like subterranean lava flows wait for the precise moment to explode and change the landscape around them. Lee is the more mature volcano; but his earthquakes create the chain reaction that stirs Austin’s. No smoke and mirrors here; just raw power.

As a perfect foil to spur the play’s development Gary Wilmes portrays Saul Kimmer, the producer hack who smarmes his way into Austin’s heart, then dumps him because he will not exact a devil’s bargain which Austin refuses to accept. Austin’s rejection of the “bargain,” enragese Lee. Wilmes is appropriately diffuse and opaque. Where does he really stand? What happened to make him turn on a dime regarding hiring Austin who has invested sweat equity and emotional integrity in a project Kimmer professed interest in? Wilmes is both authentic and the Hollywood “type,” to drive Lee and Austin against each other.

Likewise, as a foil, Marylouise Burke is LOL hysterical but frightening as their quirky mother. Her responses to their behavior are hyperbolic in the reverse and they speak volumes about how this family “functioned” in the past. She, too, helps to engine the suspense as Austin takes his power over Lee and she remains sanguine. All of the audience who are parents and especially those who have avoided the role are screaming silently in horror as the two “have at one another.” The situation and their confrontation is insane and humorous. Burke is perfect in the role as non-mediator. And Macdonald has done a magnificent job of balancing the tone and tenor of the last scene. As a result, Burke, Hawke, Dano deliver the lightening blow that helps us to realize the brothers’ intentions and the result of where they find themselves at the finale.

Ethan Hawke (standing) Paul Dano in Roundabout Theatre Company’s ‘True West,’ by Sam Shepard, directed by James Macdonald (Joan Marcus)

So much of the production resides in these incredible portrayals, of Lee and Austin’s devolution into the abyss to come to an epiphany. Caught up with that, one may overlook the artistic design. But it is so integral for it reveals the family and reflects the dynamic interactions. Superb, for example are the sound effects which augment in intensity, the frame of lights contrasting the stage into darkness for set changes, the homely, well-ordered kitchen and alcove writing area, the lovely plants and their “growth” (a field-day for symbolists), and the props. The toasting scene is just fabulous. Kudos go to Mimi Lien (Set Design) Kaye Voyce (Costume Design) Jane Cox (Lighting Design) Bray Poor (Original Music & Sound Design) Tom Watson (Hair & Wig Design) Thomas Shall (Fight Choreographer).

Sam Shepard’s play is a powerful revelation of brotherly love and hate, its design and usefulness. At the heart of our global issues resides familial relationships. To what impact on the whole is the sum of its parts? To what extent do families foment their own hatred upon themselves and the culture to exacerbate the issues? Likewise, what of families who love each other? The interplay between families and society is present but understanding it remains elusive and opaque. Shepard attempts clarity. Certainly, Lee points out that family relationships are high stakes and sometimes the warring relatives kill each other. Certainly, Austin points out that he and Lee will not kill each other over a film script. But he underestimates how far he or Lee are willing to go. How far are any of us willing to go if pushed by a relative?

Life’s uncertainty, as in the best of plays is all about surprise and not knowing what will happen in the next moments. This production of True West lives onstage because the actors are immersed in the genius of acting uncertainty that is always present. Most probably, their performance is different daily because the actors have dared to breathe out the characters whose souls they have elicited. Just W.O.W! (wild, obstreperous, wonderful)

See True West before it closes on 17 March. It runs with one intermission at the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street between 7th and 8th. You can get tickets at their website HERE.

Broadway Theater Review (NYC): ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ Starring Janet McTeer, a Stunning Portrayal

(L to R): Dylan Baker, Jason Butler Harner, Janet McTeer, Matthew Saldivar in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ by Theresa Rebeck, directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel (Joan Marcus)

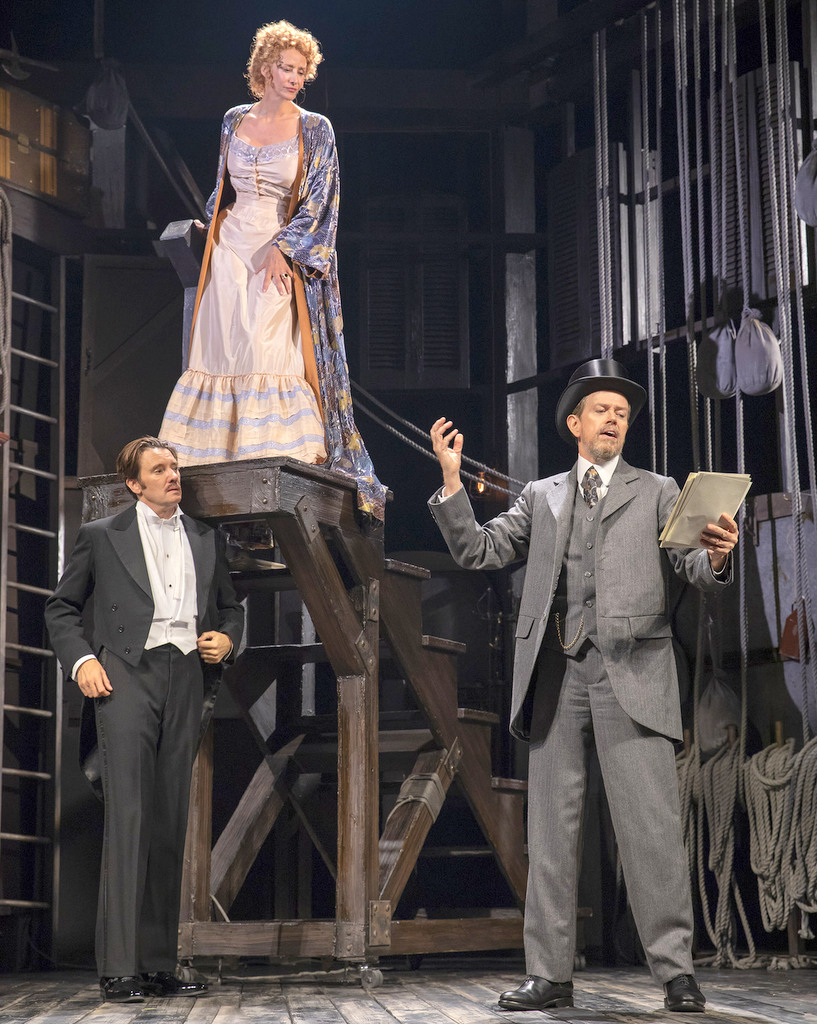

Theater scholars, dramatists, and actors are familiar with the legend of French actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), referred to as “The Divine Sarah.” Renowned for her indomitable theatrical greatness, she lived and breathed drama, melding her life and her art so that each informed the other. Alluding to this synergy of living artistry, Theresa Rebeck’s play Bernhardt/Hamlet explores the French actress’s acclaimed reinterpretation of the role of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which she imbued with her own maverick genius and courage. Examining the actress’s work, the play, thrillingly directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel, shows us thematic parallels to our times.

As Sarah Bernhardt circa 1897, confronting Shakespeare’s best-known character, Janet McTeer’s dynamism astounds. Her Bernhardt is a whirlwind of delight and shimmering brilliance. She propels the light and dark of human ethos with a range that bounds and swirls and captivates. In short, McTeer infuses her Bernhardt with an infinite variety of emotional hues so that we believe how and why Oscar Wilde referred to her as “the Incomparable One.” Additionally, we appreciate that Bernhardt was not only a visionary in enforcing her will to create opportunities for herself. For women who witnessed her heroism, she drove the platform of freedom, despite and because of a culture and society expressly controlled by men.

Dylan Baker, Janet McTeer in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet,’ Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Rebeck intimates that Bernhardt accomplished what every female actress covets. The actress intrepidly portrayed the complexity and angst of Hamlet’s human spirit with the realism of the mysterious feminine gone rogue, as only an exotic like Bernhardt could do. From her affairs with some of the crowned heads of Europe, to her re-imagining herself through her relationships with authors and playwrights, Bernhardt proved her exceptionalism. Continually, as she gained power and fame, she pushed the envelope of female propriety. And amazingly, the public adored her for it.

However, when she takes on the role of Hamlet to bring it to a larger, more profitable theater, her closest allies sound warnings. Edmond Rostand is one such ally. Jason Butler Harner skillfully portrays the poetic, conflicted author of Cyrano de Bergerac, who worked with and wrote for Bernhardt. Her lover in the play (a relationship that was rumor in real life), he must choose between his career and hers. Of course this is an irony. Rarely did women have the opportunity to have choices as Bernhardt did. In this instance, the hard choice becomes Rostand’s with regard to their work on Hamlet.

We see that the two consume each other in their relationship, which is a blessing and a curse. Harner’s potent by-play with McTeer when he challenges her “demented idea” of rewriting the iambic poetry in Hamlet’s speeches is particularly striking. His forcefulness stands against McTeer’s indomitable will in Rebeck’s exceptional characterizations. Their equivalent passion reveals the high stakes for each. Thus we appreciate the inevitability of their partnership taking a turn after he becomes famous with Cyrano and she moves on with an interpretation of Hamlet sans poetic rhythm and written by others.

Jason Butler Harner, Janet McTeer in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel, written by Theresa Rebeck (Joan Marcus)

The other ally who opposes Bernhardt’s endeavor is critic Louis, played by the stalwart and stentorian Tony Carlin. He argues with and attempts to influence Rostand in an important scene. Here we see the dangerous, shifting ground Bernhardt must negotiate as Louis questions her Hamlet choice. Perhaps the scene could be less expositional, but it is a necessary one for advancing the stakes and presenting the seeds of themes.

For example, women’s stage roles traditionally remained weak asides to fascinating, dominant male protagonists. Male roles, complex and intelligent, provided the driving dynamic that women’s roles did not. To take on a man’s role, a woman must have the power and even greater acumen and ambition to accomplish it well. Unsurprisingly, both men question whether Bernhardt has the chops to meet the Hamlet challenge.

(L to R): Jason Butler Harner, Janet McTeer, Dylan Baker in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ (Joan Marcus)

Through the real-life characters of Rostand and Louis, the playwright highlights the conflicts and problems McTeer’s Bernhardt faces. Additionally, Rebeck shows us how the staging, costuming, and promotion of this new, interpretative Hamlet must be conquered.

Wonderful in supporting roles are Dylan Baker, Matthew Saldivar, and the fine Brittany Bradford as actress Lysette. Baker portrays Constant Coquelin, Bernhardt’s acting contemporary and friend. Notably, Baker gets to have fun playing Hamlet’s father in a hysterical rehearsal scene. Experienced in the role himself, Coquelin guides Bernhardt as a quasi acting coach. Coquelin’s wisdom and sound judgment reflect his greatness as an actor. Eventually, Coquelin took on the role of Cyrano with great success. Baker’s versatility shines in his speeches as Cyrano, Hamlet’s father, and various roles including the great Coquelin himself.

Saldivar portrays Alphonse Mucha, whose artistic skills must beautify Bernhardt’s poster productions. Humorously, he expresses his upset with the task at hand. Indeed, Bernhardt’s hair, her clothing, her stature as Hamlet must enthrall and entice paying customers, a novel feat even for one of his skill. He cannot easily produce advertising artwork that will please Bernhardt, himself, and his public. Thus, as Bernhardt navigates new ground with her incredible decision to play Hamlet, so must Mucha and the others in her circle deal with the “dire” consequences. What a delicious conundrum her “simple” need to play Hamlet creates for these men whom she frustrates yet enthralls!

(L to R): Janet McTeer, Brittany Bradford in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ (Joan Marcus)

The symbolism presented by Bernhardt’s desire to enforce her will upon the culture electrifies. Subtly, when she donned the pants in Hamlet, Bernhardt symbolically freed all women from fashion folkways. Her pants-wearing signals a needed change. Women’s mores were held fast by paternalism and manifested subtly in binding corsets, bustles, and long sleeved-high collared blouses. Worn even in heat waves, these sometimes smothered the wearers, who died of heat prostration. Fashion trends, as painful as they were, laid subservient female stereotypes at women’s feet. And they dared not transgress them. Do such trends abide even today? Sometimes.

In Rebeck’s characterization of Bernhardt, the more restrictive the “thou shalt not,” the more the actress embraced it, conquering fear. In her revolutionary behavior she dismantled the “double standard.” And because she did this with aplomb, sophistication, joie de vivre, and the audacity of wit and whimsy, who could censure her? As she developed her dramatic art, she empowered herself. Memorably, McTeer takes this characterization and with precision lives it in two acts. She evokes the marvelous “Divine Sarah” and makes her a heroine because she can. How McTeer creates her Bernhardt with adroit skill, subtle intelligence and determination is a Bernhardt-like feat.

What a breathtaking reminder of magnificent women in this twisted, political tide of times. Assuredly, Rebeck’s work (McTeer’s speech to this effect rings out beautifully) remains vital and insistent. With commanding power, McTeer’s Bernhardt corrects the historical record, striking forever at the literary and dramatic canon with a tight phrase. She proclaims to Rostand that she will not play the “flower.” The night I saw the production, the women in the audience applauded these words. “I was never a flower, and no matter how much you loved how beautifully I played the ingenue, it was always beneath me. It is beneath all women.”

This moment electrifies. For though women may be compared to flowers, they are not flowers. And Bernhardt, like all women, understands. For women are power brokers, however hidden, however “passive.” Regardless of how much men nullify this truth, “woke” women grew and grow to learn and champion it. And many achieved and achieve momentous feats even from the position of “second.”

Bernhardt captured opportunity and molded destiny so it served her, not the other way around. Strengthening and illuminating her own identity, she wrote her own history, not the one the culture intended to write for her and but couldn’t. McTeer’s inspiring depiction proclaims this with every card in the deck. Indeed, when Bernhardt says about Hamlet, “I do not play him as a woman! I play him as MYSELF,” we glean the full truth of her meaning.

Rebeck wisely selects the most vital of Hamlet’s speeches. Their themes meld aptly with Bernhardt’s conundrums. Indeed, Bernhardt is “a rogue and peasant slave.” At the time she rehearses that speech, she, like Hamlet, divines how an actor uses his skills to portray a character. The double meanings are ironic. But unlike Hamlet, Bernhardt is active, assertive. As Hamlet struggles with acting crazy to hide the knowledge of the truth of his father’s murder, she struggles with a Hamlet too passive to kill. Indeed, the humor comes in watching Bernhardt’s frustration at portraying an “inactive” Hamlet who comes up with philosophical obstacles to delay killing Claudius.

Janet McTeer in ‘Bernhardt/Hamlet’ by Theresa Rebeck, directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel (Joan Marcus)

Rebeck interweaves in a complex way Hamlet’s speeches to emphasize Bernhardt’s conflict in deciding how to approach and interpret the role. One must work to catch all the ironies. So revisiting the play to enjoy this profound rendering is worthwhile.

Through active dialogue, we learn of Bernhardt’s promotional savvy and ability to reinvent herself for every decade. Naturally, this excites comparisons to today’s long-lasting actresses and others who could learn a thing or two from Bernhardt. Without fear, she capitalizes on rumor, innuendo, and extraordinary behavior that’s verboten for women. Cleverly, she makes critics her friends and generously remembers those who might have turned enemies.

Never an invisible woman, she will play men’s roles. In an affirmation about playing Hamlet and being a woman, she states to Rostand: “Where is his greatness? Where? Is it not in his mind, his soul, his essence? Where is mine? What is it about me you love? Because if in our essence we are the same, why am I otherwise less?”

Thus, Rebeck’s choice of this pivotal, “make or break” moment in Bernhardt’s career is an inspired, complicated one. The turning point reveals the grist, bravery, and revolutionary fervor Bernhardt required of herself to overturn centuries of dramatic tradition. Bernardt’s choice to conquer the greatest role written for men propels her to theatrical heaven. It is sheer artistic genius in a time when women were the “incapable,” “inferior” ones mastered by man’s sham invincibility. Bernardt/Hamlet through the seminal performances of McTeer and the ensemble informs and encourages us to realize that Shakespeare also speaks of women when Hamlet says, “What a piece of work is man. How noble in reason…”

Assuredly, kudos go to the spectacular artistic team. I particularly loved the sets (Beowulf Boritt), costumes (Toni-Leslie James), and hair (wig design by Matthew B. Armentrout). Lighting is by Bradley King and original music and sound design by Fitz Patton.

Bernhardt/Hamlet will be a multiple award winner. It is a must-see TWICE! This Roundabout Theatre Company production runs at the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street. The show until 11 November. Visit the Roundabout website for schedule and tickets.