Blog Archives

Kara Young and Nicholas Braun Fine-Tune Their Performances in ‘Gruesome Playground Injuries’

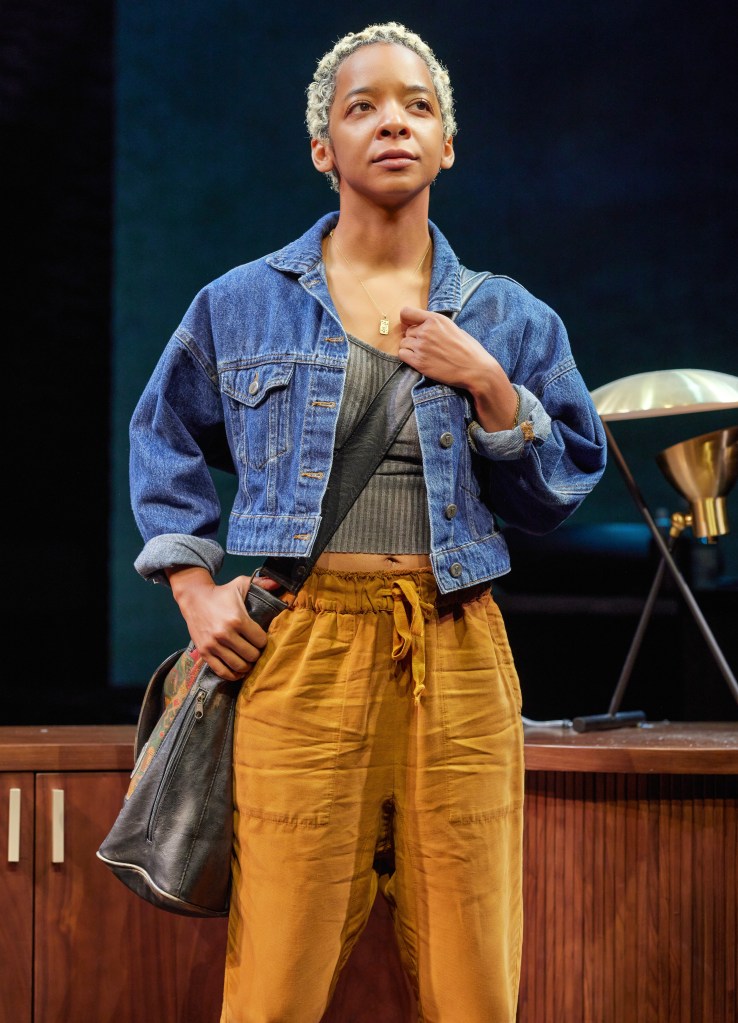

What do people do when they have emotional pain? Sometimes it shows physically in stomach aches. Sometimes to release internal stress people risk physical injury doing wild stunts, like jumping off a school roof on a bike. In Rajiv Joseph’s humorous and profound Gruesome Playground Injuries, currently in revival at the Lucille Lortel Theater until December 28th, we meet Kayleen and Doug. Two-time Tony Award winner Kara Young and Succession star Nicolas Braun portray childhood friends who connect, lose track of each other and reconnect over a thirty year period.

Joseph charts their growth and development from childhood to thirty-somethings against a backdrop of hospital rooms, ERs, medical facilities and the school nurse’s office, where they initially meet when they go to seek relief from their suffering. After the first session when they are 8-year-olds, to the last time we see them at 38-year-olds at an ice rink, we calculate their love and concern for each other, while they share memories of the most surprising and weird times together. One example is when they stare at their melded vomit swishing around in a wastepaper basket when they were 13-year-olds.

How do they maintain their relationship if they don’t see each other for years after high school? Their friends keep them updated so they can meet up and provide support. From their childhood days they’ve intimately bonded by playing “show and tell,” swapping stories about their external wounds, which Joseph implies are the physical manifestations of their soul pain. After Doug graduates from college, when Doug is injured, someone tips off Kayleen who comes to his side to “heal him,” something he believes she does and something she hopes she does, though she doesn’t feel worthy of its sanctity.

Joseph’s two-hander about these unlikely best friends alludes to their deep psychological and emotional isolation that contributes to their self-destructive impulses. Kayleen’s severe stomach pains and vomiting stems from her upbringing. For example in Kayleen’s relationship with her parents we learn her mother abandoned the family and ran off to be with other lovers while her father raised the kids and didn’t celebrate their birthdays. Yet, when her mother dies, the father tells Kayleen she was “a better woman than Kayleen would ever be.” There is no love lost between them.

Doug, whose mom says he is accident prone, uses his various injuries to draw in Kayleen because he feels close to her. She gives him attention and likes touching the wounds on his face, eyes, etc. Further examination reveals that Doug comes from a loving family, the opposite of Kayleen’s. Yet, he may be psychologically troubled because he risks his life needlessly. For example, after college, he stands on the roof of a building during a storm and is struck by lightening, which puts him in a coma. His behavior appears foolish or suicidal. Throughout their relationship Kayleen calls him stupid. The truth lies elsewhere.

Of course, when Kayleen hears he is in a coma (they are 28-year-olds), after the lightening episode, she comes to his rescue and lays hands on him and tells him not to die. He recovers but he never awakens when she prays over him. She doesn’t find out he’s alive until five years later when he visits her in a medical facility. There, she recuperates after she tried to cut out her stomach pain with a knife. She was high on drugs. At that point they are 33-year-olds. Doug tells her to keep in touch, and not let him drift away, which happened before.

Joseph charts their relationship through their emotional dynamic with each other which is difficult to access because of the haphazard structure of the play, listing ages and injuries before various scenes. In this Joseph mirrors the haphazard events of our lives which are difficult to figure out. Throughout the 8 brief, disordered, flashback scenes identified by projections on the backstage wall listing their ages (8, 23,13, 28, 18, 33, 23, 38) and references to Doug’s and Kayleen’s injuries, Joseph explores his characters’ chronological growth while indicating their emotional growth remains nearly the same, as when we first meet them at 8-years-old. In the script, despite their adult ages, Joseph refers to them as “kids.”

Toward the end of the play via flashback (when they are 18-year-olds), we discover their concern and love for for each other and inability to carry through with a complete and lasting union as boyfriend and girlfriend. When Doug tries to push it, Kayleen isn’t emotionally available. Likewise when Kayleen is ready to move into something more (they are 38-year-olds), Doug refuses her touch. By then he has completely wrecked himself physically and can only work his job at the ice rink sitting on the Zamboni.

Young and Braun are terrific. Their nuanced performances create their characters’ relationship dynamic with spot-on authenticity. Acutely directed by Neil Pepe, we gradually put the pieces together as the mystery unfolds about these two. We understand Kayleen insults Doug as a defense mechanism, yet is attracted to his self-destructive nature with which she identifies. We “get” his protection of her because of her abusive father. One guy in school who Doug fights when the kid calls her a “skank,” beats him up. Doug knows he can’t win the fight, but he defends Kayleen’s name and reputation.

The lack of chronology makes the emotional resonance and causation of the characters’ behavior more difficult to glean. One must ride the portrayals of Young and Braun with rapt attention or you will miss many of Joseph’s themes about pain, suffering and the salve for it in companionship, honesty and love.

In additional clues to their character’s isolation, Young and Braun move the minimal props, the hospital beds, the bedding. They rearrange them for each scene. On either side of the stage in a dimly lit space (lighting by Japhy Weideman), Young and Braun quickly fix their hair and don different costumes (Sarah Laux’s costume design), and apply blood and injury-related makeup (Brian Strumwasser’s makeup design). In these transitions, which also reveal passages of time in ten and fifteen year intervals, we understand that they are alone, within themselves, without help from anyone. This further provides clues to the depths of Joseph’s portrait of Kayleen and Doug, which the actors convey with poignance, humor and heartbreak.

Gruesome Playground Injuries runs 1 hour 30 minutes with no intermission through 28 December at the Lucille Lortel Theater; gruesomeplaygroundinjuries.com.

‘Purpose’ Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins’ Riotous Play, Directed by Phylicia Rashad

In Purpose, Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins’ satiric family expose directed by Phylicia Rashad, we meet a patriarchal Black American civil rights icon, Solomon “Sonny Jasper (Harry Lennix), who is forced to confront his disappointments and foibles as his family gathers to celebrate the homecoming of his eldest son and namesake, Solomon “Junior” Jasper (Glenn Davis). Navigating the audience through treacherous familial waters with asides and intermittent, pointed narration, the youngest son Nazareth “Naz” Jasper (Jon Michael Hill), explores his family’s complicated legacy as he attempts to confront issues about his own identity and future.

Currently running at the Hayes Theater until July 6th, this ferocious, edgy and sardonic send up of Black American political and religious hypocrisy resonates with dramatic power. Its superlative performances and Rashad’s fine direction, make it a must-see. Importantly, in typical Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins style, the tour de force with jokes-a-plenty raises questions. It prompts us to reflect upon our own life intentions, as we examine the Jasper family’s dynamic through the acute perspective of the endearing, sensitive, vulnerable and authentic Naz. Hill is just terrific in a role which requires heavy lifting throughout.

As the play opens we note the subject matter and foundation upon which Jacobs-Jenkins’ moralistically satiric drama rests, namely the Jaspers (think along the lines of Jesse Jackson), whose heritage boasts of leaders in civil rights, congress and the protestant church. Todd Rosenthal’s lovely, well-appointed, Jasper family home represents prosperity, upward mobility and the success of the celebrated Black political elite. Solomon Jasper was Martin Luther King, Jr.’s heir apparent in the civil rights movement.

However, among other questions the play asks is, what happened to the substance and efficacy of the movement, considering the current “state of the union” under MAGA Party president Donald Trump, whose cabinet has no Black American member? What are the legacies of the Jasper’s faith? What is the heritage of their former Black radicalism, which Naz calls into question throughout the play, as the evening explodes into tragicomedy in front of unintended witness Aziza Houston (Kara Young)? As a result of the evening with the Jaspes, Aziza is horrified to see her civil rights icons, Solomon and Claudine, smashing her respect for them to smithereens during the family imbroglio in Act I.

Via an intriguing flashback/flashpresent device, Naz exposes and illustrates how the family’s shining history becomes obliterated by circumstances in the present “state of the family union,” which has not lived up to their patriarch’s illustrious expectations. Ultimately, Solomon Jasper, too, may be counted as not living up to his own personal expectations, a fact revealed by the conclusion of the second act, which further adds to his hypocrisy for giving Naz a hard time about his sexually, abstemious, personal choices..

With increasing intensity, the upheavals occur by the end of the first act and augment into further revelations and complications well into the second, until the wounds exposed are too great to ignore. Naz’s final synopsis and soulful, poignant comments solidify at the conclusion bringing this family retrospective together. His questioning wisdom leaves us as he is left, wondering what is the trajectory of this once august Jasper legacy, which Naz has chosen not to perpetuate. Not going into politics or the church, Naz selected a career in photography where he communes with nature’s beauty and peace.

Jacobs-Jenkins’ work is filled with contrasts: truth and lies, health and sickness, moral uprightness and moral turpitude. In fact the contrast of the outer image of the Jasper calm and sanctity versus the inner corruption and turmoil becomes evident with Jacobs-Jenkins’ character interactions throughout, heightened by Naz’s confidential asides.

Additionally, this contrast of superficial versus soul depth is superbly factored in by Rashad and Todd Rosenthal’s collaboration on set design. Initially, all is peaceful in their gorgeous home set up by matriarch Claudine Jasper (the excellent Latanya Richardson Jackson). The home’s beauty belies any roiling undercurrents beneath the family’s solid, upright probity. Perfection is their manufactured brand, which Aziza has bought hook, line and sinker as a Jasper fan.

To continue with the Jaspers’ “brand,” the inviting great room boasts a comfortable and lovely open layout-living room and dining room-backed by a curved staircase to the second level of bedrooms off the landing. The dark peach-colored walls are beautifully emphasized with white trim molding. The cherry wood furniture and cream colored sofa color-coordinate with the walls. The sofa is accented with appropriate pillows. Interspersed among furniture pieces are obvious antique heirlooms. Indeed, all is perfect with matching table runners and dining room tablecloth and napkins and dinnerware tastefully selected for its enhancing effect.

Prominently featured is the Jasper family heritage and legacy, a large portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. proudly displayed on the first level, and a lesser portrait of political/cultural heir apparent, Solomon “Sonny” Jasper on the second floor landing. Surrounding the Sonny Jasper portrait are framed photos chronicling the civil rights warriors and family, shining their historical significance. When Aziza first arrives and is welcomed desperately by Claudine who fears Naz’s not bringing any woman home means he is gay, Aziza is gobsmacked by the house. Seeing the portraits and Solomon Jasper, she realizes who Naz really is. She is over the moon slathering blandishments to Sonny. Thrilled, she can’t help but take selfies with the Jaspers to send to her mom, a mutual fan. Naz is beyond humiliated and surreptitiously pleads with her to leave.

What does Naz know about his family that he fears Aziza will discover? If Aziza doesn’t leave quickly, his mother’s hospitality to divine who Aziza is will make sure she stays. Indeed, Jackson’s Claudine never fails in her intentions.

Against the storied backdrop of their illustrious past that Aziza worships, the garish present unfolds at dinner. It is the celebration of Junior’s homecoming and reunion with the family since his thirty month prison stay for embezzling campaign funds. Junior’s behavior is one of the gravest disappointments that Sonny holds against his son. For him it is unforgivable that his namesake who was to take his place has tarnished the Jasper name with corruption.

Thus, when Junior presents a birthday gift to Claudine, of the letters she wrote to him in prison in a lovely book, Sonny scoffs, especially after reading a particularly mundane letter. (Lennix’s reading of a sample letter is hysterical). Then, Sonny questions Junior who wants to exploit their family name and go on tour with the book of Claudine’s letters, and Claudine, lifting up the hellishness of his imprisonment like a martyr.

Ironically, bitterly, humorously, Sonny airs his disgust that Junior would present himself as a Nelson Mandella, as if Junior’s prison experience was in any way equivalent to the horrors of imprisonment used as a tool of oppression and racism throughout US history. Sonny is especially livid because Junior’s crimes ripped off his father and Blacks who supported him. Additionally, the time Junior did was easy because Sonny used his influence to get Junior into “a minimum security playground.” Though it is revealed that Junior has bi-polar disorder, (the scene when Glenn Davis manifests this is superb), Sonny lacks empathy for Junior. He dismisses his illness and says he got caught where other politicians don’t get caught because Junior is stupid.

At dinner the dour Morgan (Alana Arenas), Junior’s wife, sits quietly at first. After Junior uplifts Claudine, Morgan claims neither he nor the Jaspers helped her through Junior’s mental breakdown. Nor does he acknowledge her visiting him through the prison experience with a present. Morgan rips into him and the family. They are “hucksters,” who don’t care about her and “have no sense of responsibility or remorse.” Listening to the Jasper’s accountants, Morgan signed their joint tax returns that implicated her in tax fraud with Junior. She has lost her career and will have to do time in prison for an error that she was ignorant about, trusting the family to not mislead her.

Thus, the artifice gradually peels away, shaped by the characters’ ever increasing digs at each other and Naz’s humorous perspective. To top it off, despite her promise to Naz that she will keep quiet, Aziza reveals how she trusts Naz to be the sperm donor for their child. This piece of information is a stick of dynamite for this religious family who chaffs at unmarried young people sleeping together. Then, when Claudine and Morgan go head to head and Morgan calls the family’s “honesty” into question and accuses Sonny of having “his fiftyleven other kids scattered all over this damn country,” Claudine loses it and gets violent.

Ironically, the act ends with the patriarch blaming Claudine, “I have let you build this house on a foundation of self-deceit.” Sonny loudly declares the time is now for “redemption” and a “new era in this family – a new era of truth! Truth!”

Act II indicates how that “truth” is to come about, as Naz and Aziza argue about why she broke her promise to him. Abashedly, Naz disavows the violence that spilled out between his mother and Morgan. Meanwhile, the verbal and emotional violence has always been an undercurrent in the family that has never confronted their issues. In other words, the dissembling, the lies and the deceit have augmented until “enough is enough.” Aziza, caught up in the fray rethinks what she has seen and no longer has any wish to have Naz’s child from their “illustrious” DNA. Additionally, she has learned not to lionize any other civil rights icon or celebrity easily, again. Celebrities, like the Jaspers, are not saviors or worthy to be made into icons. They have clay feet if you see them up close and personal.

Though the first act sails smoothly, the second act digresses in part with Naz’s extensive dialogue and explanations, which might have been slimmed down. Nevertheless, as we learn about each family member’s complications, the intensity shifts. Though there is less humor, there is incredible poignancy and each of the actors have their moments to shine. Not only do we note the profound aspects of character complexity, we understand the difficulty of attempting to maintain an oversized legacy of greatness when one is an imperfect human being. Indeed, the one who comes out best appears to be Naz, until the conclusion. It is then we understand how the family has impacted him and in response, he has sent himself spinning into his own chaos, which he will have to unravel for himself. So do we all as we deal with our own legacy, heritage and family dysfunction.

Purpose is brilliant, if a tad unwieldy. However, the ensemble cracks sharply like lightening. Rashad has a deep understanding of Jacobs-Jenkins’ themes, dynamic characters, prickly relationships and the sub rosa levels of meaning in the interactions. The pace is lively despite the playwright’s wordiness and keeps the audience engaged.

Kudos to the creative team including those not already mentioned: Dede Ayite (costume design), Amith Chandrashaker (lighting design), Nikiya Mathis (hair & wig design), and Bob Milburn & Michael Bodeen (sound design). Purpose runs two hours fifty minutes with one intermission at the Helen Hayes Theater on 44th between 7th and 8th. https://purposeonbroadway.com/

‘Purlie Victorious,’ a Riotous Look in the Backward Mirror of 1960s Southern Racism

White power structures die hard. However, they do fall apart when the younger generation helps to topple them.

This is particularly true in Purlie Victorious, a Non-Confederate Romp Through the Cotton Patch, currently in revival on Broadway at The Music Box. It is the next generation that overwhelms the cement-like apparatus of noxious, white paternalism in Ossie Davis’ trenchantly funny play. Thus, we cheer on the pluck, humor, audacity and cleverness of the young reverend Purlie Victorious Judson, exquisitely inhabited by the unparalleled Leslie Odom, Jr. of Hamilton fame. Odom, Jr. leads the cast with his kinetic and superb performance.

The premise for the play that initiates the action is steeped in hope and youthfulness-the righting of a an ancestral wrong symbolically-the despotic terrorism of slavery’s oppressive violence. With mythic actions and intentions Purlie returns home to the Georgia plantation where he was raised, to claim his inheritance and take back the honor which racist owner Ol’ Cap’n Cotchipee siphoned off from his family through peonage (servitude indebtedness).

How Purlie does this involves a fantastic and hysterical scheme, eliciting the help of the adorable Lutiebelle Gussie Mae Jenkins (the riotous Kara Young). Purlie, who met Lutiebelle in his travels, intends to pass her off as his Cousin Bee, who will charm Ol’ Cap’n (the perfect foil, Jay O. Sanders), into giving her the $500 cash that was bequeathed to their aunt by her wealthy lady boss. After succeeding in the scheme to dupe Ol’ Cap’n, Lutiebelle will give Purlie the cash. With cash in hand, Purlie will purchase and restore the Old Bethel Church, so he can preach uplifting freedom to the sharecroppers, who are enslaved by peonage to Ol’ Cap’n.

As Purlie relates his scheme to family, Missy Judson (the fine Heather Alicia Simms), and Gitlow Judson (the riotous Billy Eugene Jones), they avow it won’t work. At first, Gitlow refuses to take any part because he is one of Ol’ Cap’n’s favorite “darkies.” Gitlow has risen to success through his amazing cotton picking labors. Ol’ Cap’n bestows upon him the anointed status of chief oppressor of the “colored folk” working for Ol’Cap’n. He keeps them nose to the grindstone at their backbreaking work.

However, when Purlie introduces his relatives to Lutiebelle, and unleashes his persuasive and inspiring preaching talents on his kin, they give the scheme a whirl. What unfolds is a joyous, sardonic expose of all the techniques that Black people used when dealing with the egregious, horrific, white supremacists of the South, represented by Ol’ Cap’n, The Sheriff (Bill Timoney), and The Deputy (Noah Pyzik).

The irony, double entendres and reverse psychology Purlie and family use when confronting Ol’ Cap’n are sharp, comedic, and of moment. Though Ol’ Cap’n owns the place and exploits the sharecroppers using indebtedness, on the other hand, we note that Gitlow is able to manipulate Ol’ Cap’n with his “bowing and scrapping” which, as we are in on the joke, is brilliantly humorous.

It is in these moments of dramatic irony when Ossie Davis’ arc of development reveals how the characters work on a sub rosa level, that the play is most striking and fabulous. The enjoyment comes in being a part of knowing that Purlie and the others are able to “get over,” while Ol’ Cap’n is unable to see he is “being had.” Additionally, with the assistance of Ol’ Cap’n’s clever, forward-thinking son, Charlie (the wonderful Noah Robbins), Ol’Cap’n is completely flummoxed, having missed all the undercurrents which indicate he is being duped.

The actors, beautifully shepherded by director Kenny Leon, effect this incredible comedy, which also has at its heart a deadly, serious message.

Black activist, writer, actor, director Ossie Davis wrote Purlie Victorious, which premiered on Broadway in 1961 at a time when Martin Luther King, Jr. had strengthened the Civil Rights Movement and celebrities were taking a stand with Black activists. In fact, Martin Lurther King, Jr. saw the production and was pictured with the cast, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, his wife, who portrayed Lutiebelle.

Particularly in the final speech that Purlie delivers, we can identify with the important themes of a unified human family being together on an equal plane. It is a message that is particularly poignant today, considering the political divisiveness of the white nationalists, a throwback to the Southern racists of the 1960s, like Ol’ Cap’n, who Jay O. Sanders makes as human as possible to allow his racial terrorism to leak through with humor. Because of Sanders’ balanced portrayal, Ol’ Cap’n is an individual who has become his own hysterically funny caricature and stereotype, precisely because he is so obtuse in his self-satisfied mien as their “great white father.”

In the play Davis’ themes about the cruelties of peonage resonate today in the corporate structures which have kept wages low while giving CEOs 500 times what their average workers make. Indeed, the play resonates with the idea of servitude and keeping the labor force however indebted (with student loans, loans, mortgages, credit card debts), so that individuals must work long hours to keep one step ahead of financial ruin. We note the parallels between then and now. The inequities then are in many ways reflective of current economic disparities between the classes, allowing for very little upward mobility from one generation to the next.

It is this that Purlie attacks and preaches against throughout the play. It is this inequity and enslavement indebtedness that Purlie intends to educate Black people about, so that they become free and whole. It is for this reason Purlie wants to purchase and renovate Bethel Church, where he will preach his message of freedom. As we listen, we also realize that the message resonates with everyone, regardless of race, except, of course, the white oppressors, who stand to lose their power, lifestyle and privilege.

This material loss, which would be their spiritual gain, is unthinkable to them. Davis’ indirect message is that this is the oppressors’ greatest sin. They don’t see that by internalizing the defrauding and inhumane values of white supremacy, they are the truly hellish, loathsome monsters, the “other,” they seek to destroy. The destruction only happens to them, while the strengthening happens to those they oppress.

Kenny Leon’s direction expertly guides his actors, moving them with perfectly timed pacing and comedic rhythm. The play develops from broad farce and hi jinks and moves to an ever-expanding roller coaster ride of frenetic humor and excitement. We note Purlie’s desperation and frustration with Ol’ Cap’n’s arrogance and presumptions about Black inferiority, which Purlie will not scrape to. Of course, Idella Landy (the wonderful Vanessa Bell Calloway), who has been a mother to Charlie, with love, influences him to override his father’s brutal attitude toward their family. Indeed, Charlie adopts the Judsons as the family he chooses to be with, rather than his arrogant, ignorant, abusive father.

Leon manages to seamlessly work the staging and find the right balance so the irony and true comedy never becomes bogged down in the seriousness of the message. Because of the lightheartedness and good will, we are better able to see what is at stake, and why Charlie comes to the rescue of his Black family, against his own father, who is an inhumane obstructionist past his prime.

The set design by Derek McLane allows the action to remain fluid and shape shifts so that we move from the Judson family home, to Idella Landy’s kitchen, to the Bethel Church at the conclusion. With Emilio Sosa’s costume design, Adam Honore’s lighting design, Peter Fitzgerald’s sound design and J. Jared Janas hair, wig and makeup design, the creatives have manifested Leon’s vision for the play. Additional praise goes to Guy Davis’ original music, and Thomas Schall’s fight direction.

This revival of Purlie Victorious is a wonderful comedic entertainment that also has great MAGA meaning for us today. For tickets to this must-see production that runs without an intermission, go to their Box Office on 239 West 45th Street or their website https://purlievictorious.com/tickets/

‘Cost of Living’ Broadway Review: Are Lives Lived Well or Wasted?

What price do we place on our own inherent value? What is the rock bottom cost we have to pay to live with dignity and be fulfilled emotionally, physically, materially? These subtle questions as well as questions about our need for respect and life-giving emotional and spiritual connection compose the themes of Martyna Majok’s well-acted four-hander, Cost of Living directed by Jo Bonney currently, at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.

The 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning play originally debuted at the Williamstown Theater Festival in 2016, and appeared off Broadway in Manhattan Theatre Club’s production at New York City Center in 2017. Currently, Manhattan Theatre Club presents Majok’s Broadway debut, adapting to the larger stage and stretching out the precisely appropriate scenic design of the various New Jersey apartments of differing economic scale by Wilson Chin. From the ensemble Gregg Mozgala and Katy Sullivan originated their roles of the differently abled John and Ani. Kara Young as Jess and David Zayas as Eddie portray the able bodied caretakers who learn what physical and emotional skills are required to help the differently abled deal with the most intimate and personal body functions when they cannot.

The actors make a terrific ensemble despite a play that has flawed construction and sometimes is unnecessarily confusing during the first hour of the two hour play which speeds by in some parts and slow walks in others. But for the exceptional performances one wouldn’t completely understand the import of the present immediate timeline of the first scene as it connects to the last scene. Both provide the frame that holds together the substance of the rest of the events which take place in flashback four months prior.

Thanks to the superb David Zayas who portrays Eddie, an out of work truck driver and former alcoholic who is clear-eyed and specific in his discussion of his wife who has passed, we eventually unravel the mystery of events which take place between Eddie and wife Ani (Katy Sullivan), Jess (Kara Young) and John (Greg Mozgala) that unspool in the past and spin into the present changing the direction of circumstances for Eddie and Jess.

If Majok didn’t order the play as a frame with flashbacks, the relationships of the couples would have popped even more than they do. However, it is a way to hide the contrivances that promote surprise and twists in Majok’s exploration of the relationships between Jess and John, Ani and Eddie. These twists set up the concluding scene which effects the most beautiful and resonating of Marjok’s themes of connection and communication. The last scene is the uplifting high-point of the play, carefully shepherded by Bonny and wonderfully acted by Zayas and Young.

The structural difficulty occurs in the initial scene with Eddie’s solo speech to an unidentified individual (the audience) in the setting of a bar with a lovely row of shining alcohol bottles decoratively strung with Christmas lights. Eddie tells us the hipster bar is in chic Williamsburg, Brooklyn where he has been enticed from Bayonne, New Jersey by cheeky texts. The anonymous individual was given his deceased wife’s phone number which Eddie used to text her to not feel so desolate and alone. After being pestered by the texter into curiosity and a desire to stave off loneliness, Eddie decides to accept the offer to meet at the Williamsburg bar on the snowy night in December.

Zayas’s Eddie, in this sprawling introductory opening scene, where he relays some of his backstory about his alcoholism and split with his wife, remains charming, funny and generous. He easily wins us over by offering us (the anonymous guy in the bar) a drink for listening to him as he promises not to launch into the doom and gloom he feels since his wife died. We go along for the pleasant ride, not realizing when he leaves that this is a prologue, one section of the frame in the immediate present. Thus when the scene switches completely to another setting (thanks to Wilson Chin’s upscale scenic design representing John’s apartment) we don’t realize we are in a flashback four months earlier in another situation. We discover it when the director and the playwright unfold the dialogue introducing two characters unrelated to Eddie.

This might easily have been clarified with a notation in the program of setting change. Prosaic and uncool? Hardly. For the purpose of clarification and the heightening of the vital themes and arc of the relationships which the playwright presents and explores, the details would have launched us into the profound characterizations earlier to appreciate the depth of the play. Thus, we must catch ourselves up in the time switch to a flashback that this is John’s apartment in Princeton at a time in September.

Jess (Kara Young) and John (Greg Mozgala) are complex individuals coming from completely different socioeconomic backgrounds and physical and emotional states, key points for what later unfolds. By degrees we learn that Jess and John went to Princeton where John’s stylish apartment is located. John is a wealthy grad student with cerebral palsy (Mozgala has cerebral palsy). Jess graduated with honors and now works in bars where her tips are large. However, she needs the caretaker job John offers for additional money. As both do the interview dance, we are struck by Jess’ unadorned personality and direct authenticity. John must win us over as he comes off as a presumptuous ironist who is taken with himself.

Whether his personality is a pose to cover for extreme inferiority in a culture and society that prizes the beautiful, athletic, young and whole, or his wealth has allowed him to leverage his superior act, we realize that both Jess and John act in control. Like any relationship, even a work one, trust must be gained and built up. Jess is guarded and wary; John is overly confident and wry.

In the next scene switch from John’s apartment in Princeton, we meet Eddie’s wife Ani who is alive at this point in the flashback which she states takes place in September. She is in her new apartment where she will live with outside help. She is a quadriplegic, having suffered a horrific car accident in the previous months where surgeries saved her life but couldn’t restore her use of her arms and both legs which were amputated at the knee. Obviously, Ani is infuriated with Eddie and curses him out as a matter of course, trying to get him to leave. He is moved by her condition and feels guilty and responsible for being with another woman, a cause of their separation and filing papers for divorce. However, because they are still legally together, she is on his insurance. And he kindly suggests she stay on it even after they are divorced.

The play by degrees establishes the warmth of feeling between Ani and Eddie, Jess and John as the caretakers help the differently abled shower, bathe and finish their personal toilet. The intimacy of the activities are matched by the honesty of their conversations so we are struck by the humanity and concern shared by each individual in the couple who helps the other in an exchange. Anit gives Eddie emotional support as he helps her physically. Jess receives a listening ear in John as she becomes adept at transferring him to the shower seat and helps him cleanse himself.

We learn more about Jess’ immigrant background, her mother’s returning home because of financial difficulty and her struggle to send money home to her, during John’s and Jess’ time together. With the once married couple, the former love between Eddie and Ani is still evident but it has changed and deepened. Eddie could just move away from Ani. However, he emotionally needs to be with her and is happy that he can help her and watch her when the agency and nurse call on him because her regular caretakers sometimes cancel.

The dynamic relationships created by the superlative actors make this play ring out with hope, even though in the last two flashbacks, the darkness comes and we fear for the characters we have come to like. Also, selfishness is revealed in one of the characters whose clever manipulations are completely unexpected and underestimated. It is a shocking and hurtful reveal and the character never recovers our good will because he has made himself unworthy of it. This twist is seamlessly drawn as Majok plucks at our heart strings and upends our expectations. However, the last scene between Zayas’ Eddie and Young’s Kar is perfection in dialogue, acting, direction. In the actors’ living each moment, we realize why there is nothing like theater.

Cost of Living reminds us of our weaknesses and the consolation that if one feels lonely, all experience the ache even those partnered up. It is a fact of life that neither money nor marriage can salve; it is the cost of being alive, for we are each in ourselves individual and alone. However, only communication, truth and honesty with others can light the way for connection that is sincere and life affirming. It is then that the cost of being alive is worthwhile.

Kudos to Jessica Pabst (costume design) Jeff Croiter (lighting design) Rob Kaplowitz (sound design) Mikaal Sulaiman (original music) and Thomas Schall (movement consultant).

For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2022-23-season/cost-of-living/