Blog Archives

‘Our Town’ Starring Jim Parsons, Katie Holmes, Richard Thomas in a Superb, Highly Current Revival

Part of the magic of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town is its great simplicity. In Jim Parsons’ (Stage Manager), facile, relaxed, direct addresses to the audience lie the profound themes and templates of our lives. The revival of Our Town directed by Kenny Leon with a glittering cast of renowned film, TV and stage actors, reinforces the currency and vitality of Wilder’s focus on human lives, and the seconds, minutes, hours and days human beings strike fire then are extinguished forever, eventually forgotten as the universe spins away from itself. A play about the cosmic journey of stars and their particle parts in human form in a small representational town on earth, Our Town is iconic. Leon’s iteration of this must see production runs at the Ethel Barrymore Theater until January 19th.

The three act play is in its fifth Broadway revival since the play premiered in the 1930s. This most quintessential of American plays appeared on Broadway when the United States was in the tail end of the Depression during a period of isolationism, and concepts about Eugenics from American researchers had been adopted by the Third Reich to effect their legal platform for genocide. At a curious turning point in American history before a conflict to come, Wilder’s work about life and death in small town Grovers Corners in the fiercely independent state of New Hampshire represented a symbolic microcosm of life everywhere. Perhaps, the play’s themes, especially in the third act were a harbinger, and a warning. In its theme, “we must appreciate life with every breath,” was prescient because WWII was coming to remove millions in a devastation that was incalculable, noted by many as the “deadliest conflict in human history.”

Despite its stark ending and in your face “memento mori,” Wilder’s play found and finds an appreciative audience because of its universality and unabashed assertions about our mortality, walking unconsciousness, and refusal to remain “awake” to the preciousness of our lives.

Indeed, the play has continued to be widely read and performed globally in commercial theater, as well as educational institutions. Leon’s production is no less riveting than other revivals and is even more elucidating and vital in its stylistic dramatic urgency. This is especially so at this point in time, at the eve of a crucial period in our body politic, when we are deciding between two pathways. Do we want to continue to uphold the inexorable verities expressed in Wilder’s themes about living with as much equanimity as possible in a democratic nation that respects the peaceful transfer of power as Grovers Corners symbolizes in Leon’s production? Or do we jettison the rule of law, and the peaceful transfer of power in the US Constitution for a dictatorship in which not all lives are equal or valuable but one life must be bowed down to unequivocally?

Leon’s direction stands in with the former, primarily in the production’s inclusiveness of a diverse group of actors representing Grover’s Corner’s accepting, and non judgmental townsfolk as they go about their business. The business of being human, Wilder divides into three segments (Daily Life, Love and Marriage, Death). Through the omnipotent Stage Manager, which Jim Parsons portrays with a low-key, pleasant avuncular and philosophical style, we quiver at his ironic, pointed rendering of life on this planet.

At the top of the play, the brisk, time-conscious stage manager, after detailing the ancient geological foundation of Grovers Corners, introduces us to the two families which Wilder highlights throughout the play to note their arc of development. Doc Gibbs (Billy Eugene Jones), the local physician, and Mr. Webb (Richard Thomas), the editor of the Sentinel are neighbors. At the turn of the century their wives, like most married women of the time, stay at home, do the housework and prepare meals, none of which is relieved by modern mechanical devices. We learn Mrs. Gibbs (MIchelle Wilson), and Mrs. Webb (Katie Holmes), “vote indirect,” which is to say women are considered incapable of making a rational voting decision.

However, the Stage Manager’s two words hold more weight than he seemingly intends to give them. Instead, he glides by the import of sociopolitical trends because it is unrelated to the cosmic picture alluded to by Rebecca Gibbs (Safiya Kaijya Harris), at the end of Act I. Indeed, the universal themes Wilder drives at do not focus on specific political details. Wisely, Leon takes his cues from the script having Parson’s Manager speak about the titles of the acts as dispassionately and unnuanced as possible. Importantly, Leon “gets” that the functioning of the town, symbolically rendered and opaquely stylized is how Wilder achieves the ultimate impact of the powerful conclusion about appreciating life each day we live it, as insignificant and boring as it may seem at times.

After we meet the children at a breakfast prepared by Mrs. Gibbs and Mrs. Webb via pantomime, the Stage Manager provides the locations of key places like the Post Office, the newspaper office, etc., and reminds us of the town routines, i.e. the train’s arrival and departure, milk and paper deliveries, etc. In the another part of the act, we meet the children who get hooked up in Act II, George Gibbs (Ephraim Sykes), and Emily Webb (Zoey Deutch).

Also, clarified is the town “problem,” Simon Stimpson (Donald Webber, Jr.), who we meet as the play opens when Simon Stimpson conducts the choir in a lovely song. Stimpson becomes the subject of gossip because choir members know he drinks and is drunk a good deal of the time. Mrs. Soames (Julie Halston) gossips about Stimpson and is hushed up by Mrs Gibbs, who tells a little white lie that Stimpson is getting better, then later tells her husband he is getting worse. Webber, Jr. is masterful in the small part. Clues are given about Stimpson’s future, as the character is referred by townspeople in Act I, with some questioning and not knowing “how that’ll end.” Eventually, the Stage Manager shows us how it “ends,” in Act III with Stimpson commenting about life and Mrs. Gibbs responding to him. Whose view should we accept? It, like this production, is open to interpretation.

Three years pass between Act I and Act II, and Parson’s Manager officiates at the marriage between Emily Webb and George Webb, after showing the event which reveals that these two individuals are special and their relationship which is “interesting” is grounded in being truthful to one another. The marriage scene which has been a bit tweaked and slimmed down from the original play, does include the Stage Manager philosophically discussing marriage and particularly George and Emily’s marriage when he says, in part, that he has married over two hundred couples and continues, “Do I believe in it? I don’t know. Once in a thousand times it’s interesting.” Again, we realize the profound comment and question what “interesting,” means.

In the last act which the production speeds to with no intermission as it clocks in at a spare one hour and forty-five minutes, Wilder’s vaguely spiritual metaphors are touching and poignant, despite the production’s bare bones lack of sentimentality. Warning, here is the spoiler, so don’t read the rest of the review if you are unfamiliar with Our Town.

Wilder’s third act resonates with symbols of death, as “the Dead” sit together on chairs as Parson’s unemotional Stage Manager describes the hillside cemetery. Importantly, the lack of Parsons’ emotion stirs the audience deeply. And in Leon’s production, the stylization in the previous acts makes the power of Emily’s return to see and live through her 12th birthday even more potent. Newly dead in childbirth, the Stage Manager gives Emily the privilege, which he says all the dead have, to return to a day in her life to relive it. The morning of her birthday, Emily watches herself, symbolically live without the realization that she will be dead in less than two decades later.

After commenting at how young her parents look and recognizing their love and affection, her pain at her obliviousness to life’s beauty overcomes her and she wants to leave to go back to the cemetery, a lovely spot where her brother Wally, Mrs. Gibbs, Simon Stimpson and Mrs. Soames wait for “something to come out clear.”

Emily’s dialogue is breathtaking and Deutch gets through it with less emotion and passion than is probably required for the audience to feel the reality of her words. “So all that was going on, and we never noticed.” And perhaps more emotion is needed as Emily asks the Stage Manager, “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it? – every, every minute?” The audience in shock silently answers for itself as the Stage Manager responds.

This is the cruel and truthful heart of the play, especially experiencing it through the character of Emily and the Stage Manager’s comforting but remote words which somehow fall ironically when Parsons says, “No. The saints and poets,maybe – they do some.” However, only in death does Emily realize the suffering pain of not appreciating and being grateful for every fabulous, wondrous moment of life.

Certainly, Wilder needs to hit his audience over the head, and they walk out silently receiving the message, then days later forget it. However, for the moments when Leon, Parsons, the cast and the superb and lovely lighting and staging hold us, we “get it.” And we are grateful for teachable moments received through the actors’ fine efforts, the creative team’s craft and Leon’s minimalist stylization. And we appreciate the rich fullness of each gesture, word and grace delivered to make us get in touch with ourselves in our own Grovers Corners’ life.

Kudos to all involved in this magical production. Thornton Wilder’s Our Town runs one hour forty-five minutes without an intermission at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre (243 West 47th Street). https://www.ourtownbroadway.com/?gad_source=1&gclsrc=ds

‘Home,’ The Journey of a Lifetime in Wisdom and Poetry, Review

With lyricism and poignancy in this Roundabout Theatre Company revival of Home, directed by Kenny Leon, Samm-Art Williams spins a story of life’s rhythms, spanning decades during the Great Migration, the time when thousands of Blacks moved with hope to northern cities, leaving Jim Crow’s economic oppression and lynching violence behind. Williams’ covers distances and cultural spaces, all the while evolving his protagonist’s mental, physical and spiritual well being. Home has been receiving a “warm welcome,” at the Todd Haimes Theater, after a prolonged lapse since its original production in 1980 when it was Drama Desk and Tony-award nominated.

Starring Tory Kittles as Cephus Miles, newcomers Brittany Inge and Stori Ayers, portray a multiplicity of characters (40+) from family members to the men and women positively or negatively rubbing up against Cephus on his journey to self-realization. Williams’ representatives move us from a tobacco farm in Cross Roads, North Carolina to a prison in Raleigh, to a northern city (New York), of subways, a roiling, feverish, chaotic place for Cephus that spills out a never-ending cacophony of noise, colors, struggle and conflict.

Then finally, a battered, bruised and reformed drug and alcohol-addicted Cephus has had enough. By that point, he has died to his ego to return home to the rich black soil he thought he had lost, and God’s grace, which was apparently late in coming, but actually was with him all along.

It takes wisdom to know that God has been with him, which he has obviously gained as it is subtly expressed by the ersatz Greek chorus (Inge and Ayers), who introduce the theme of God’s grace which we and Cephus learn abides throughout his life. (“If there was ever a woman or man, who has everlasting grace in the eyes of God. It’s the farmer woman… and man.”) As Inge and Ayers repeat these affirmations as Woman Two and Woman One at the top of play and in a brief song and rhythmic summation of the life of the farmer/sharecroppers who labored and sweat under the sun, then left for the cities, they state that one “fool” came back. And Cephus, “the fool” sits in a rocking chair center stage listening to them.

Cephus, is anything but a fool. His travels have converted him to a contented man of wisdom who has learned, through patience, the hard lesson of God’s everlasting grace. Though we don’t realize it at the top of the play, Cephus has returned from his odyssey. The townspeople’s myths swirl around him (via Inge and Ayers), and town children (Ayers and Inge), whisper the rumors, “Old Cephus Miles. Can’t be saved,” that “he’s dead,” that “he’s a ghost,” as they throw rocks at the windows of the “haunted house,” where he has returned to claim “I’m alive,” “I’m flesh, blood and bone.”

The play is Cephus’ lyrical and dramatic life told in flashback, at times in and out of sequence, like an epic tone poem with the chorus (Ayers and Inge), at the ready to activate his narration, an exegesis exploring and explaining the spiritual text of the grace that threads through his life.

Against a backdrop of tobacco plants, corn stalks, golden lighting by Allen Lee Hughes and a projection of distant acres of crops to the horizon line (the projection changes when Cephus moves to the city), Leon employs a symbolic minimalism of set and props (set design-Arnulfo Maldonado). He adjusts scene changes based on the dialogue and simple objects, a box, a chair, a drop-down cross. Dede Ayite’s costumes and Ayers and Inge’s hair (Nikiya Mathis-hair & wig design), essentially remain the same with a few additions and subtractions (hats, scarves, hair let down-a wig). Miraculously, Leon’s simplicity which fits the thematic, lyrically flowing style of this work, is not only fitting, it is revelatory. However, it is also arcane and opaque at times.

Ultimately, Williams/Leon’s symbolic translation of Cephus’ seemingly “ordinary” existence becomes a spiritual guidepost that focuses on uplifting the souls of those who witness it. Thus, we gradually understand why Cephus quietly dismisses the extraordinarily horrid conditions of racism in the Jim Crow south. Slowly we realize how he withstands injustice related to his poverty and lack of education. That impact is demonstrated when Cephus, unlike those whites who paid to get bone spur deferments or were deferred by college, is drafted during the Viet Nam war. Many Blacks who were unable to get such deferments fought and died in the jungles. He reads the letters of two friends who warn him off going to fight.

But fear didn’t stop Cephus from serving. God’s commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” stops him. A religious conscientious objector, he spends five years in prison because he refuses to kill in battle. After his imprisonment, Cephus gives up sharecropping and heads north. He has tethered his happiness to Pattie Mae, the love of his life, and thinks he may get an education and “improve” himself like she did. Her mother prompted her to go north, get an education, became a teacher and forget about marrying Cephus because she was “better” than he.

However, at this point in his life, destitute and without friends or shelter, somehow Cephus ends up in the city where life befalls him as he waits for God to “come back from Miami” and help him deal with countless issues. Life takes an unbelievable turn for him and he questions God’s absence. With humor Williams relates Cephus’ travails and shares stories out of the traditions of citified Black folk and stories from his country childhood, i.e. his time in the hayloft with Pattie Mae, gambling in the cemetery with friends, loss of close family members and more. Home presents the important and crucial moments in Cephus’ life under the long arm of God, who he prays to, sometimes.

Caught up in the emotionalism of his pain, Cephus, delivered in an incredible performance by Kittles, draws us in and keeps us engaged with humor bytes and memes that reoccur and have their final concluding day. The ending is more than a satisfactory relief and it is the first time we see Cephus grin from ear to ear. Indeed, he has come home in relating and reliving his journey with us with the dogged and wonderful supporting help of Inge and Ayers.

Williams’ style and poetic form is easy listening, as one catches the music inherent in the language and the word beats. At times, however, the pacing and lack of theatricality are uneven and I found myself drifting, despite the tremendous performances of the actors. Overall, the ensemble and their direction by Leon are smashing, as is Williams’ Homeric view which provides a look at war and battle in the human psyche filtered through the American Black experience.

This is one to see. Unless it is extended, the end date is July 21.

Home. Todd Haimes Theatre. 224 West 42nd Street with no intermission. https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/

‘Hamlet,’ Kenny Leon’s Dynamite Version, Free Shakespeare in the Park

There are more iterations of Hamlet presented globally in the last fifty years than are “dreamt of in your philosophy.” To that point director Kenny Leon’s version of Hamlet, currently at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park until August 6th, provides an intriguing update of the son for whom time is so “out of joint,” he is unable to seamlessly and speedily avenge his father’s murder. Leon’s version shapes a familial revenge tragedy. Once set on its course, dire events cannot be averted, for at the core is the initial corruption, “the primal eldest curse, a brother’s murder” that “smells to heaven.” From that there is no turning, until justice is served, the sooner the better.

In this 61st offering of Free Shakespeare in the Park, we immediately note the conceit of corruption and its ill effects to skew the right order of things, making them “out of joint,” off-kilter. This is an important theme of the play (expressed by Hamlet) and represented by Beowulf Boritt’s set, some of which is a wrecked-out remnant of his design from Leon’s pre-Covid production of Shakespeare’s comedy, Much Ado About Nothing.

That 2019 design sported a resplendent, brick, Georgian mansion that stylistically conveyed the wealth and rectitude of its Black, lordly owners rising up in a progressive South. Hope was represented by a “Stacy Abrams for President” campaign sign proudly displayed on the side of the building. A towering flagpole and American flag patriotically stood like a sentinel at the ready. Peace and order reigned.

It is not necessary to have seen Much Ado About Nothing to understand the ruination and disorder foreshadowed by Boritt’s Hamlet set which coherently synthesizes Leon’s themes for his modernized version. In one section a tilted smaller version of the former Georgian house appears to be sinking off its foundation. On stage left, an SUV is tilted off center, undrivable, in a ditch. The Stacy Abrams’ sign is torn and displaced on the ground like discarded trash. And the American flag with its long flagpole angled toward the ground signals distress and a “cry for help.”

The only ordered structure is the cutaway of a building center stage (used for projections), whose door the characters enter and exit from.

Boritt’s set design suggests “something is rotten” unstable and “out of joint” in this kingdom. Themes of devolution are foreshadowed. From unrectified corruption comes disorder which breeds chaos and dark energy, out of which destruction and death follow. And all of this springs from the unjust murder of the deceased in the coffin that is draped in an American flag and placed center stage. It is his life which is celebrated by the beautiful singing of praise hymns at his well-attended funeral in the prologue of Leon’s Hamlet. It is his life that is memorialized by the huge portrait of the kingly father in military dress which hangs watchful, presiding over events from its position on the back wall of the only part of the set that is not wrecked and disarrayed.

Cutting Act I scene i (soldiers stand on guard watchful of an attack from Norway), Leon opens with the elder Hamlet’s funeral. A Praise Team joined by a Wedding Singer, who we later recognize to be Ophelia (the golden-voiced Solea Pfeiffer), sing with beautiful harmony. Jason Michael Webb created the music and additional lyrics which set out the Godly tenets that all are importuned to follow or live by. To their downfall they don’t and this is manifested in tragedy.

Importantly, the first three songs are taken from the Bible. The first is from Ecclesiastes (“To everything there is a season). Then follow Matthew 5 (“To show the world your love, I’m goona let it shine”) and I John 5 (“When you go on that journey you go alone”). The last song that Ophelia sings is composed of lines from a love poem that Hamlet wrote for her.

The songs intimate the former moral rectitude and divine unctions found in the former Hamlet’s kingdom. Ironically, the memorial service represents the last peace that this kingdom will appreciate. As the set indicates, wrack and ruin have already begun. The scenes after the funeral represent declension and growing darkness. And after old Hamlet is buried, nothing good follows.

Numerous cuts (scenes, lines, characters) abound in Leon’s version. His iteration presents questions about the disastrous consequences of familial revenge which is different from Godly justice suggested by the songs. Importantly, Leon’s update (sans scene i) gets to the crux of the conflict with scene ii, the marriage celebration of Claudius (the terrific John Douglas Thompson and Gertrude (Lorraine Toussaint is every inch Thompson’s equal). We note their public affection for one another, which Hamlet later intimates is a lust-filled marriage in an “unseemly bed.” The partying has followed fast upon the old Hamlet’s burial, to the dismay and depression of his loyal son.

It is during the festivities when the sinister intent of the new king and duped mother Gertrude chide Hamlet (the fabulous Ato Blankson-Wood). They suggest he put off his mourning clothes, “unmanly grief” and depression for it is “unnatural.” Already, the cover-up has begun and Hamlet is the one individual Claudius must be circumspect about as the rightful heir to a throne which he usurped.

Gertrude importunes Hamlet to remain in the kingdom instead of returning to his studies in Wittenberg, and dutifully, he obeys, stuck with the daily reminder of his father’s death and mother’s “o’er hasty marriage.” This version emphasizes Claudius’ sincerity covering over his suspicion and fear of Hamlet. He is happy to keep him under his watchful eye. Throughout his magnificent portrayal, Thompson’s Claudius gradually reveals his underlying guilt and fear for his crimes of regicide and fratricide. We see his behavior grow more and more paranoid about Hamlet as the conflict between them grows and Hamlet unloads snide remarks on Claudius, Polonius and all those who are obedient to the usurper king as a provocation.

Leon’s version is a familial revenge tragedy which eliminates any reference to Norway or Prince Fortinbras seeking justice for his father’s death in battle with Denmark. Leon is unconcerned with Norway and Fortinbras. The conflict in his Hamlet is internal to Denmark, a divided kingdom like “an unweeded garden, rank and gross in nature.” Divided against itself, with brother vs. brother and son vs. uncle, and Gertrude the exploited, seduced pawn, Claudius’ guilt is a canker worm which gnaws at him. Likewise, gnawing at Hamlet after his father’s ghost’s visit, is the knowledge of what has to be done. But he maintains, “cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right.”

All is covert and the truth is covered up. Polonius and Claudius spy on Hamlet to divine why he is “mad,” and Hamlet acts mad and rejects Ophelia’s love during the process of divining whether the ghost is telling the truth. Intrigue, chaos and darkness augment and have their way with the innocent and guilty. For Hamlet, the “time is out of joint.” An intellect, he is “blunted” (the ghost later says) from making the correct decisions or acting upon them in a timely fashion. The darkness that Claudius has set loose taints Hamlet and every principal character that must show obeisance to King Claudius’ illegal reign.

Key to the argument of choosing vengeance vs. justice is the enthralling scene when Hamlet meets his father’s ghost. Initially, the creative team (Jeff Sugg’s projections, Allen Lee Hughes’ lighting design, Justin Ellington’s sound design) present the father’s ghost on the back wall with projections on the portrait and the wall, accompanied by the ghost’s booming, shattering voice, which commands Hamlet’s obedience.

But at the description of the murder, the ghost possesses Hamlet. Blankson-Wood’s performance of the ghost consuming his soul is phenomenal and physical. He arches his back with the jolt of spirit possession and then rights his gyrating body as his father’s voice spews wildly from him, eyes rolled back, arms waving, the very picture of the demonic that Horatio (the fine Warner Miller) warned Hamlet might “tempt him to the flood.” At once frightening and mesmerizing, the possession enthralls us and changes Hamlet. It is a dynamic, successful scene showing the decline in the goodness from the initial praise songs to the devolution of the spirit’s will demanding vengeance. We are thunderstruck. Blankson-Wood’s authenticity frightfully convinces us of the spirit’s potential for evil misdirection into a vengeance which is not just and will bring devastation.

After the ghost leaves the vessel it inhabited and Hamlet swears Horatio and Marcellus (Lance Alexander Smith) to secrecy, Hamlet’s fate is sealed. He moves toward faith in the ghost, farther away from the light-filled unctions in the songs at his father’s funeral. Now, there is no “showing love” and “shining one’s light.” Intrigue and acting “mad” and conspiracy and cover-up overtake the mission of the kingdom. Hamlet toys with and ridicules Polonius (Daniel Pearce gives a humorous, organically funny portrayal) and does the same with Ophelia in a powerful scene, eschewing his love for her. Pfeiffer’s Ophelia shows her devastation and shock. His behavior is a complicating truth for everyone and it intensifies Hamlet’s conflict with Claudius.

Knowing Hamlet’s madness is not for Ophelia’s love, Claudius grows more paranoid and guilt laden. Clearly, when the actors make their presentation of the dumb show (Jason Michael Webb’s song “Cold World” is superb), and Hamlet presents ‘The Murder of Gonzago,’ he and Horatio see that Claudius’ guilty conscience is made manifest in ire and defensiveness. Though this scene is truncated, as is Hamlet’s description of how the actors should proclaim their speeches, no coherence is lost. Claudius runs away, his soul uncovered. Hamlet is convinced vengeance is the right course of action. But he has allowed himself to be misguided. Nothing good will come of following the ghost’s lead.

Leon truncates the minor speeches, retaining those that convey Hamlet’s angst at being stuck in the kingdom which is a prison. He can’t commit suicide (“To Be or Not to Be”) because his morality and fear of death forbids it. Stuck in Denmark, everyone is a potential enemy except Horatio. He uses coded speech with everyone especially Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who Claudius/Gertrude have engaged to spy on him. Ato Blankson-Wood delivers the key soliloquies powerfully with insight as he makes the audience his empathetic confidante who understands his intellect has chained him to inaction. We are drawn into his plight, but become frustrated when his determination falters.

The paramount event where his intellect intrudes happens when Claudius is praying in the church (fine stylized staging). Coming upon Claudius, Hamlet rejects the opportunity to kill him because he thinks Claudius is confessing his sins and getting right with God. However, it is a missed opportunity which Hamlet squanders because Claudius’ prayers fail (“my words fly up, my thoughts remain below; words without thoughts never to heaven go.”). Claudius realizes to receive forgiveness he would have to give up the throne, Queen and his cover-up which he will never do.

Hamlet lacks proper discernment and moves from his bad decision to impulse. Not killing Claudius in the church, he rashly and mistakenly kills Polonius, assuming incorrectly that Claudius quickly ran up to Gertrude’s room. The stakes are raised for Claudius and Hamlet. Polonius’s death missing body incense Claudius who is overwrought with fear knowing his enemy Hamlet has put a target on his back.

Once more, the “time is out of joint,” and Hamlet defers vengeance and subjects himself to Claudius, finally revealing where Polonius’ body is. For Gertrude’s sake, Claudius sends Hamlet away with the orders for others to kill him in a plan that fatefully backfires.

Leon’s version has clarified the stakes for Claudius to escape accountability, manipulating Laertes (Nick Rehberger) from killing him by blaming Hamlet. Thompson conveys each of these cover-ups with precision. Also, clarified is Blankson-Wood’s angst and struggle confronting his father’s murderer. His use of irony as a weapon to prick Claudius’ conscience is superbly rendered as are his soliloquies whose philosophical constructs tie him in emotional knots. Hamlet, knowing that he is stuck in a morass with no way out, recognizes that like the other characters, he is on a collision course with destiny and ruination which is foreshadowed at the beginning with Boritt’s set.

Also, clarified in this version is Toussaint’s Gertrude who is in a state of ambivalence and guilt stirred by Hamlet’s antic behavior, which she suspects is his response to her marrying Claudius. When their confrontation occurs after Hamlet kills Polonius, she knows her relationship with Claudius must be thrown over, yet she hesitates and discusses Hamlet with Claudius ignoring Hamlet’s wise counsel. The doom she recognizes in Ophelia’s madness will only bring more sorrows, a trend which both Claudius and Gertrude comment upon. Toussaint’s description of Ophelia’s drowning is heartfelt and mournful.

The flow of events coheres because the through-line of Claudius and Gertrude in conflict with Hamlet is maintained with intensity. Stripping Norway from the action and leaving Fortinbras out of the conclusion is to the purpose of Leon’s emphasis of the familial tragedy. The contrast of the good son and man of action who achieves justice (Fortinbras) with Hamlet’s flawed son of inaction who is Fortune’s fool, exacerbating destruction via revenge gone wrong would have pleased Queen Elizabeth I. Contrasting the two Prince’s and showing the heroic one in Fortinbras is an encouragement of how royalty should rule. However, it doesn’t fit with the themes that Leon emphasizes, especially that a “house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Hamlet concludes with the slaughter of two families tainted by their association with a corrupted king, out from which there is no release except death. A final theme current for our time suggests that unless individuals stand against usurpers of power, the usurper and all who are his accomplices by not bringing him to justice will pay the forfeit of their lives and fortunes.

However, only Miller’s Horatio understands the full story of Hamlet and the striving between vengeance and justice. That vengeance brings disaster is why the ensemble finishes with the actors’ song that they sang when Hamlet first meets them. It is poignant and true and heartfelt when the spirit of Ophelia joins them and together they sing, “I could tell you a tale, God’s cry. It could make the God’s cry.”

Kudos to the ensemble and the creative team who carry Leon’s vision of Hamlet into triumph. These include those not already mentioned: Jessica Jahn’s colorful costume design, Earon Chew Nealey’s hair, wig and makeup design, Camille A. Brown’s choreography and Gabriel Bennett for Charcoalblue and Arielle Edwards for Delacorte’s sound system design.

For tickets to this unique Hamlet which has one intermission, go to their website https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2223/fsitp/hamlet/

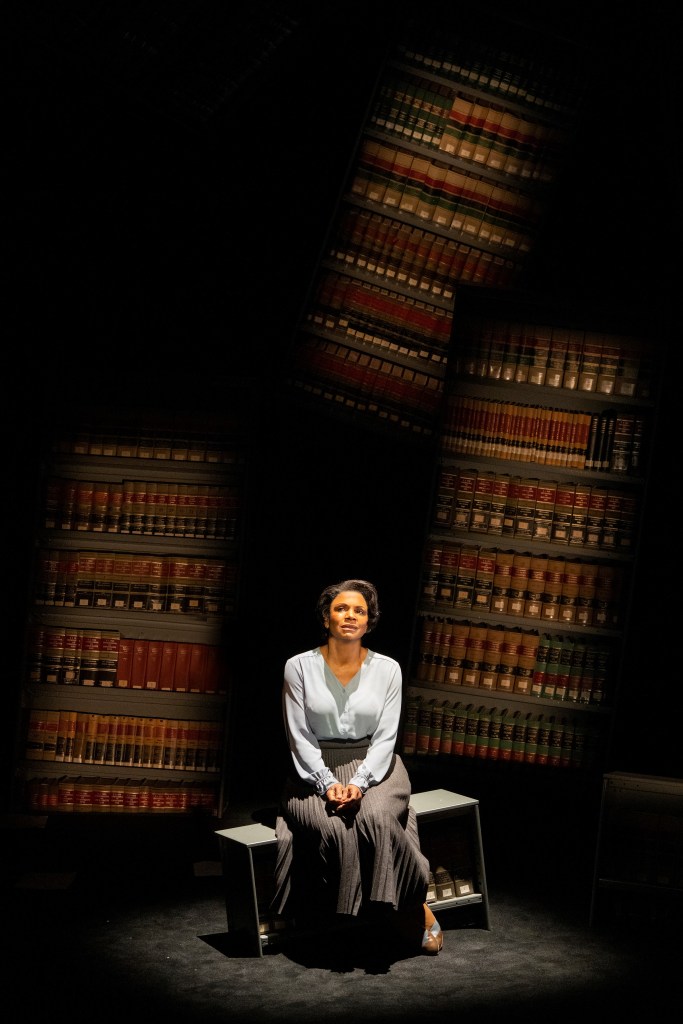

‘Ohio State Murders,’ Audra McDonald’s Performance is Stunning in This Exceptional Production

For her first Broadway outing Adrienne Kennedy’s Ohio State Murders has been launched by six-time Tony award winner Audra McDonald into the heavens, and into history with a magnificent, complexly wrought and richly emotional performance. The taut, concise drama about racism, sexism, emotional devastation and the ability to triumph with quiet resolution is directed by Kenny Leon and currently runs at the James Earl Jones Theatre until 12 February. It is a must-see for McDonald’s measured, brilliantly nuanced portrayal of Suzanne Alexander, who tells the story of budding writer Suzanne, in a surreally configured narrative that blends time frames and requires astute listening and thinking, as it enthralls and surprises.

This type of work is typical of Kennedy whose 1964 Funnyhouse of a Negro won an Obie Award. That was the first of many accolades for a woman who writes in multiple genres and whose dramas evoke avant garde presentations and lyrically poetic narratives that are haunting and stylistically striking. As one who explores race in America and has contributed to literature, poetry and drama expressing the Black woman’s experience without rhetoric, but with illuminating, symbolic, word crafting power, Kennedy has been included in the Theater Hall of Fame. In 2022 she received the Gold Medal for Drama from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The Gold Medal for Drama is awarded every six years and is not bestowed lightly; only 16 individuals including Eugene O’Neill have been so honored.

This production of Ohio State Murders remains true to Kennedy’s wistful, understated approach to the dramatic, moving along an arc of alternating emotional revelation and suppression in the expose of her characters and their traumatic experiences. Leon and McDonald have teased out a 75 minute production with no intermission, intricate and profound, as Kennedy references and parallels other works of literature to carry glimpses of her characters’ complexity without clearly delineating the specifics of their behaviors. In the play much is suggested, little is clarified. Toward the unwired conclusion we find out a brief description of how the murders occurred and by whom. The details and the motivations are distilled in a few sentences with a crashing blow.

Much is opaque, laden with sub rosa emotion, depression, heartbreak and quiet reflection couched in remembrances. The most crucial matters are obviated. The intimacy between the two principals which may or may not be glorious or tragic is invisible. That is Kennedy’s astounding feat. Much is left to our imaginations. We can only surmise how, when and where Suzanne and Robert Hampshire (Bryce Pinkham in a rich, understated and austere portrayal) who becomes “Bobby” got together and coupled when Suzanne supposedly visited his house. Their relationship mirrors that of the characters in Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy. It is this novel which first brings the professor and student together in mutual admiration over a brilliant paper Suzanne writes and he praises.

What is mesmerizing and phenomenal about Kennedy’s work is how and why McDonald’s Suzanne follows a process of revelation not with a linear, chronological storytelling structure, but with an uncertain, in the moment remembering. McDonald moves “through a glass darkly,” unraveling recollections, as her character carefully unspools what happened, sees it anew as it unfolds in her memory, then responds to the old and new emotions the recalled memories create.

Audra McDonald is extraordinary as Suzanne Alexander, who has returned to her alma mater to discuss her own writing which has been published and about which there are questions concerning the choice of her violent images. The frame of Suzanne’s lecture is in the present and begins and ends the play. By the conclusion Suzanne has answered the questions. Kennedy’s circuitous narrative winds through flashback as Suzanne relates her experiences at Ohio State when she was a freshman and her movements were dictated by the bigotry that impacted her life there.

In the flashback McDonald’s Suzanne leaps into the difficult task of familiarizing us with the campus and environs, the discrimination, her dorm, roommate Iris Ann (Abigail Stephenson) and others (portrayed by Lizan Mitchell and Mister Fitzgerald), all vital to understanding Suzanne’s story about the violence in her writing. Importantly, McDonald’s Suzanne begins with what is most personal to her, the new world she discovers in her English classes. These are taught by Robert Hampshire, (the astonishing Bryce Pinkham) a professor new to the college. Reading in wonder and listening to his lectures, Suzanne’s fascination with literature, writing and criticism blossoms under his tutelage.

Within the main flashback Kennedy moves forward and backward, not allowing time to delineate what happened, but rather allowing Suzanne’s emotional memories to lead her storytelling. After authorities expel her from Ohio State, she lives with her Aunt and then returns with her babies to work and live with a family friend in the hope of finishing her education. During this recollection she refers to the time when she lived in the dorm and was disdained by the other girls.

Kennedy anchors the sequence of events in time by using the names of individuals Suzanne meets. For example when she returns after she has been expelled, she meets David (Mister Fitzgerald) who she dates and eventually marries after the Ohio State murders. What keeps us engrossed is how Suzanne fluidly merges time fragments within the years she was at the college. She digresses and jumps in memory as she retells the story, as if escaping from emotion in a repressive flash forward, until she can resume her composure. At the conclusion, Suzanne references the murders of her babies.

Thus, with acute, truncated description that is both poetic and imagistic, McDonald’s Suzanne slowly breaks our hearts. McDonald elucidates every word, every phrase, imbuing it with Suzanne’s particular, rich meaning. Though the character is psychologically blinded and perhaps refuses to initially accept who the killer of her babies might be, there is the uncertainty that she may know all along, but is loathe to admit it to her self, because it is incredibly painful. At the conclusion when she reveals the murderer’s identity and events surrounding both murders, she is remote and cold, as is the snow falling behind outside the crevasse. At that segment McDonald’s unemotional rendering triggers our imaginations. In a flash we understand the what and why. We receive the knowledge as a gut-wrenching blow. Fear has encouraged the murderer in a culture whose violence and racism bathes its citizens in hatred.

When McDonald’s Suzanne Alexander brings us back to the present as she pulls us up with her from the recesses of her memory, we are shocked again. We have been gripped and enthralled, swept up in the events of tragedy and sorrow, senseless violence and loss. The question of why bloody imagery is in Suzanne’s writing has been answered. But many more questions have been raised. For example, in an environment of learning and erudition, how is the murder of innocents possible? Isn’t education supposed to help individuals transcend impulses that are hateful and violent? Kennedy’s themes are horrifically current, underscored by mass shootings in Ulvade, Texas and other schools and colleges across the nation since this play was written (1992). At the heart of such murdering is racism, white domestic terrorism, bigotry, hatred, inhumanity.

The other players appear briefly to enhance Suzanne’s remembrances. Pinkham’s precisely carved professor Hampshire reveals all the clues to his nature and future actions in the passages he reads to his classes from the Hardy novel, then Beowuf and in references to King Arthur and the symbol of the “abyss” he discusses in two lectures Suzanne attends. All, he delivers tellingly with increasing foreboding. Indeed, the passages are revelatory of what he is experiencing symbolically in his soul and psyche. When Suzanne describes his physical presence during the last lecture, when she states he is looking weaker than he did when he taught his English classes, it is a clue. Pinkham’s Hampshire is superbly portrayed with intimations of the quiet, profound and troubled depths of the character’s inner state of mind.

Importantly, Kennedy, through Suzanne’s revelations about the university when she was a freshman, indicates the racism of the student body as well as the bigotry of the officials and faculty, which Black students like Suzanne and Iris must overcome. There is nothing overt. There are no insults and epithets. All is equivocal, but Suzanne feels the hatred and the injustice regarding unequal opportunities.

For example it is assumed that she cannot “handle” the literature classes and must go through trial classes to judge whether she is capable of advanced work as an English major. When she tells professor Hampshire, he insists that this shouldn’t be happening. Nevertheless, he has no power to change her circumstances, though he has supported and encouraged her writing. The college’s bigotry is entrenched, as she and other Black women are discouraged in their studies and forced out surreptitiously so that they cannot complain or protest.

Kenny Leon’s vision complements Kennedy’s play. It is imagistic, minimalistic and surreal, thanks to Beowulf Boritt’s scenic design, Jeff Sugg’s projection design, Allen Lee Hughes lighting design and Justin Ellington’s sound design. At the top of the play there are two worlds. We see black and white projections of of WWII and the aftermath through a v-shaped crevasse that divides the outside culture and the interior of the college in the library symbolized by faux book cases. These are suspended in the air and move around symbolically following what Suzanne discusses and describes.

The books are a persistent irony and heavy with meaning. They sometimes serve as a backdrop for projections, for example to label areas of the campus. On the one hand they represent a lure to Suzanne who venerates literature. They suggest the amalgam of learning that is supposed to educate and improve the culture and society. However, the bigoted keepers of knowledge in their “ivory” towers use them as weapons of exclusion and inhumanity, psychologically and emotionally, harming Blacks and others who are not white or who are considered inferior. Leon’s vision and the artistic team’s infusion of this symbolism throughout the play are superb.

In the instance of the one individual who appreciates Suzanne’s writing, the situation becomes twisted and that too, becomes weaponized against her. However, that she has been invited back to her alma mater all those years later to discuss her writing indicates the strength of her character to overcome the incredible suffering she endured. At the conclusion of her talk in the present she reveals her inner power to leap over the obstacles the bigoted college officials put before her. Her return so many years later is indeed a triumph.

Leon and the creative team take the symbolism of rejection, isolation, emotional coldness and inhumanity and bring it from the outdoors to the indoors. Beyond the crevasse in the wintertime environment, the snow falls during Suzanne’s description of events. Eventually, by the end of the play, the exterior and interior merge. The violence we saw at the top of the play in pictures of the War and its aftermath has spread to Ohio State. The snow falls indoors. Finally, Suzanne Alexander is able to publicly speak of it openly and honestly after discovering there was a cover-up of the truth that even her father agreed to out of shame and humiliation.

Ohio State Murders is a historic event that should not be missed. When you see it, listen for the interview of Adrienne Kennedy before the play begins as the audience is seated. She discusses her education at Ohio State and the attitudes of the faculty and college staff. Life informs art as is the case with Adrienne Kennedy’s wonderful avant garde play and this magnificent production.

For tickets and times to to their website: https://ohiostatemurdersbroadway.com/

‘A Soldier’s Play,’ Bravura Performances by Blair Underwood and David Alan Grier

(L to R): David Alan Grier, Blair Underwood, Billy Eugene Jones in ‘A Soldier’s Play, by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company, American Airlines Theatre (Joan Marcus)

When the Negro Ensemble Company presented Charles Fuller’s A Soldier’s Play in its Off Broadway premiere in 1981, the production garnered a number of theater awards and Fuller won a Pulitzer Prize for Drama the following year. Norman Jewison directed the film version retitled A Soldier’s Story in 1984 where it was nominated for numerous awards. It has been produced in two revivals Off Broadway in subsequent decades. At last Fuller’s searing, profound work about race prejudice internalized has received its premiere on Broadway, thirty-nine years later. It is currently running at American Airlines Theatre.

With exceptional direction by the amazing Kenny Leon (Much Ado About Nothing, Shakespeare in the Park 2019) and sterling ensemble work headed up with masterful performances by David Alan Grier and Blair Underwood, A Soldier’s Play has come to Broadway with vibrant force and vigor. The dramatic arc of development revolves around solving a murder mystery. The body of Tech/Sergeant Vernon C. Waters (David Alan Grier portrays the unlikable, brutal, tragic Sergeant) is found with two bullet holes. The murder case is solved through flashbacks of scenes during the testimony of witnesses, narration and scenes unfolding in the present day 1944, Fort Neal, Louisiana.

David Alan Grier in ‘A Soldier’s Play,’ by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company, American Airlines Theatre (Joan Marcus)

Captain Charles Taylor (Jerry O’Connell in a fine performance) and his superiors take precautions with the men of Waters’ platoon Company B, 221st Chemical Smoke Generating Company. They fear that Waters’ men may engage in revenge killings against red necks in the area of Fort Neal, Louisiana. It is not clear at the outset, but Waters may have been lynched by the KKK or good ole boys who intend to keep blacks bowing and scraping. Until his murder is investigated, and more is discovered about what may have happened, Waters’ men are guarded by MPs who surround their barracks so that none of them get entangled with white townspeople. Private Hensen suggests that the Klan killed Waters because lynchings have been happening since he arrived at Fort Neal. But he may have been murdered by white officers in a racial killing. As a result, commanding officers on the base have given the case a “low priority status,” and are ready to sweep all they discover under the rug.

The consideration makes sense in 1944 during WW II. At the Fort Neal and on every base in the U.S. military, black and white soldiers are segregated in their living quarters, platoons and companies. Service in the military is as discriminatory as the “separate but equal” oppressions of the Jim Crow South. In the day to day operations, the black companies are detailed with doing the scut work and menial assignments in order to confirm that they are the inferior race. Indeed, the men have not yet been sent to Europe to fight. This is another racist assumption that they cannot be trusted, but fit the stereotypic mischaracterization of blacks being lazy, shiftless, mentally slow and cowardly.

Fuller’s play focuses on the nullifying effects of racism as blacks attempt to rise in a culture that oppresses them, and counter-productively rejects or ignores their gifts and contributions. Using the lens of the past during WWII and the backdrop of segregation in the military, Fuller brilliantly emphasizes the psychological impacts of racism which creates annihilating divisions not only between blacks and whites, but especially between blacks and blacks. An inferred theme is that as the fascist Nazis did for Germany, these behaviors also, are incredibly destructive to “the master race.”

Blair Underwood in ‘A Soldier’s Play,’ by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company, American Airlines Theatre (Joan Marcus)

Fuller’s play reveals a richness of themes, characterizations and conflicts that timelessly reflect great currency for us today with underlying institutional racism and the increasing evidence of racism unleashed by the White House. Fuller also digs deeply into the black on black abuse and crime that evidences the internalization of white oppression and denigrating values and attitudes that blacks unconsciously accept as they seek to redefine themselves culturally apart from the mordant ethics of white culture.

Leon, highlights these themes with his superb direction and vision of Fuller’s play. His is a fascinating and nuanced iteration that includes symbolism and foreshadowing manifested by Allen Lee Hughes’ lighting design and the music rendered in song by the on-point cast, elucidated by the excellent sound design of Dan Moses Schreier. At appropriate junctures in the production, beginning from the outset, Leon has the soldiers in Company B sing. We come to understand later that they are mourning one of their own. The music ties them together in a unity that cannot be breached by the racist white officers.

However, this unity must be breached by Captain Richard Davenport (Blair Underwood) a lawyer assigned to the 343 Military Police Corp Unit, if he is to discover who murdered Waters. In a devastatingly powerful, psychologically sensitive and heartfelt performance, Underwood introduces us to the racial dynamic he must confront as he analyzes the situation with objective tolerance, restraint and courage. It is an irony that in Davenport’s encounters with white officers, who would abuse his rank and his education, he stands his own ground with dignity and grace, employing the full force of his culture’s weapons (including a rumor that Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall is behind the investigation). No publicity is good publicity; if the case, which has been given low priority, is not handled properly, it could embarrass the military in a time of war.

Jerry O’Connell, Blair Underwood in ‘A Soldier’s Play,’ by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company, American Airlines Theatre (Joan Marcus)

Davenport, who is a maverick outlier, confounds the racist military officers who don’t know what to do with him and how to behave around him. He is a confident, self-realized, unbowed black man who is educationally superior to them, having achieved a law degree in addition to four years of college. Davenport’s talking “like a white man” and his staid nature and inner power particularly annoy Captain Taylor who dislikes that Davenport outranks him in intelligence and education, though they are on equal footing as Captains.

They disagree continually about Davenport’s mission, his competence, his confidence bucking the system and his insistence in interrogating and arresting white officers who might be charged with Waters’ murder. Underwood’s Davenport and O’Connell’s Taylor are authentic in their head-to-head arguments which intensify as Davenport incisively moves through his investigation. Both actors contribute to creating suspense and heightening the themes about why Waters was murdered, which gives rise to the underlying psychological and racial components that his murder reveals.

(L to R): J. Alphonse Nicholson, Rob Demery, McKinley Belcher III in ‘A Soldier’s Play,’ by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company, American Airlines Theatre (Joan Marcus)

Fuller’s depth of characterization, his wisdom and his clear-eyed perception of what it means to be black in the military and in America then and now is only enhanced and codified in this insightful rendering shepherded by Kenny Leon to perfection. Each of the relationships between and among the enlisted soldiers of Company B, Waters and the white officers reflect explosive, vital issues. The irony of the setting is that America, which is mandated to fight and destroy fascism, of course refuses to adequately confront its racist fascism at home. The white culture forces susceptible blacks to obviate their own identity and culture to embrace white culture to “thrive.” Of course by doing this, blacks must reject their own people, their own very being as they internalize the value of being white and act white to get ahead, destroying their very valuable spirit and the soul of blackness.

This mistaken assumption is exemplified by Sergeant Waters. David Alan Grier’s perceptive understanding of Waters reveals the character’s limitations and sorrows. His cruelty toward some of the men in his company is an outgrowth of venerating white values and not defining himself as having worth apart from the white cultural “successes”. Grier’s portrayal is complex and rich with nuanced meaning. He reveals Waters’ realization of how he has destroyed himself and others as the great tragedy of the play. He is stunning and sardonic in his provocation of the white officers, and it is then we realize that he cannot get untangled from the morass he has created in abusing himself and others. He has become the epitome as the white man’s creature who perpetrates the most pernicious elements of discrimination and hatred by oppressing himself and attacking his own people.

(L to R): Warner Miller, Nnamdi Asomugha, Blair Underwood, ‘A Soldier’s Play,’ by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company (Joan Marcus)

Grier’s Waters is miserable and is looking to be put out of this hell he has created. And the execution he cannot effect for himself in a suicide, he provokes another to accomplish for him. His death is paralleled with another in the production. The other death is senseless genocide that Waters prompts, of course, because daily, Waters must cut out his black identity from his own soul. And in a twisted, passive aggressive revenge against blacks, whom he sees as not rising to the white man’s standards, he obliterates them. It is a slow, horrific process of self-destruction and fraud that the men in his company recognize, but cannot articulate. If they could they might be able to beneficially codify how to stop the genocidal practice of destroying oneself to “fit in” which Waters exemplifies.

In addition to the exceptional performances already mentioned are the performances of J. Alphonse Nicholson portraying Private C. J. Memphis and Rob Demery portraying Corporal Bernard Cobb. Nicholson’s Memphis is sensitive, loving and accepting. His speech to his close friend Corporal Cobb (who, too, is kind and elucidating) is poignant and filled with longing. We immediately understand where he is going in his life and why; his choice is symbolic and consequential; it is the cry of freedom from strictures which have so bound up Waters as to make him daily harm himself and target those like Memphis and Cobb.

The Company in ‘A Soldier’s Play,’ by Charles Fuller, directed by Kenny Leon, Roundabout Theatre Company, American Airlines Theatre (Joan Marcus)

Waters’ act of provocation and Memphis’ act are different sides of the same coin. That their behavior is directed against themselves and the black race in genocidal acts caused by racism and fascism, runs to the soul of American and is Leon’s and Fuller’s indictment against white supremacy. Indeed, if we look hard and deep enough in our justice system, in our economic inequality, in our educational inequality, the same threads of injustice prevail today. They are frighteningly manifest in the fascism of white supremacists who look to find their “place in the sun” which they fear they have lost. It is an incredible irony considering that they are blind, deaf and dumb to their own cultural creations and backwash reflected by institutional racism and discrimination that ultimately is destroying the white culture along with the black in a nihilistic seething inhumanity.

The conclusion delivered by Underwood’s Davenport that sums up the case findings and aftermath is emotionally riveting. It is as heartfelt and poignant as Nicholson’s speech as Private C. J. Memphis. But where Memphis has chosen his decision, Davenport is both blessed and cursed with infinite understanding. Indeed, we see that his recounting of what has transpired in Fort Neal is a memorial to these individuals. Also, it is triumphant in its prophesy for the future of civil rights achievements and the hoped for end of racism and discrimination which has yet to be realized even to this day in America. And finally it is a cry of anguish from the depths of Davenport’s soul: of frustration, of anger, of a cry to the heavens for justice. The interpretations are many as a capstone to this incredible production whose themes are paramount for us today.

Thankfully, Fuller’s play and this production put these themes front and center. It is impossible not to feel them, see them, know them, especially in recognizing current attempts to destroy our imperfectly realized democratic form of government by moving it toward fascism and dictatorship.

Once again kudos to the ensemble acting whose unity and and realism helped to create a memorable, thrilling night at the theater. And kudos also go to the creative team: Derek McLane (set design) Dede Ayite (costume design) Allen Lee Hughes (lighting design) Dan Moses Schreier (sound design) Thomas Schall (fight choreographer).

The must-see A Soldier’s Play is running at American Airlines Theatre (42nd St. between 7th and 8th) with one intermission until 15 March. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Much Ado About Nothing,’ Directed by Kenny Leon, Powerful Messages for an America in Crisis

The ensemble in William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

From Emilio Sosa’s vibrant costumes to Beowulf Boritt’s impeccable set design (a landscape of roses, luscious, ripe-for-the-plucking peaches on the Georgia peach tree, the luxuriant front lawn, the Georgian-styled, two-story mansion-representative of an orderly, harmonious, idyllic world), this update of Much Ado About Nothing resonates as an abiding Shakespearean classic. Director Kenny Leon’s vision for the comedy with threads of tragedy evokes a one-of-a-kind production with currency and moment. This is especially so as we challenge the noxious onslaught of Trumpism’s war on democratic principles, our constitution and the rule of law.

Directed with a studied reverence for eternal verities, Leon, with the help of his talented ensemble, carves out valuable takeaways. They focus on key elements that gem-like, reflect beauty and truth in Shakespeare’s characterizations, conflicts and themes. By the conclusion of the profound, spectacular evening of delight, of sorrow, and of laughter, we are uplifted. As we walk out into a shadowy Central Park, our minds and hearts have been inspired to shutter fear and cloak our souls against siren calls that would lure us from reason into irrational insentience and hatred.

Grantham Coleman (foreground) Hubert Point-Du Jour, ensemble, William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

Kenny Leon has chosen for his setting a wealthy black neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia, whose Lord of the realm, Leonato (Chuck Cooper’s prodigious, comedic and stentorian acting talents are on full display), shows his political persuasion with prominent signs on the front and side of his house that read, “Stacey Abrams 2020.” The impressive “Georgian-style” mansion which could be out of East Egg, the upper class setting of The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, is ironic with the addition of its advocating support for Abrams.

With this particular set piece, we note Leon’s comment on black progress toward a sustained economic prosperity amidst a backdrop of oppression, if one considers the chicanery that happened during Abrams’ run for the 2018 gubernatorial election. It also is reminiscent of the house of the racist, misogynistic villain of Gatsby, the arrogant, presumptuous Tom Buchannan and other such elites (i.e. wealthy conservatives), who give no thought to destroying “people and things” of the underclasses with their policies. Yet Lord Leonato and his friends and relatives are not turned away from justice and empathy for others. This, the director highlights through this Shakespearean update, whose characters seek justice and truth and encourage each other to abide in kindness, love and forgiveness.

(L to R): Margaret Odette, Tiffany Denise Hobbs, OLivia Washington, Danielle Brooks William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

Leon approaches his vision of justice through love by weaving in songs and music. At the outset Leon incorporates such music with a refrain sung by Beatrice (the inimitable Danielle Brooks):

“Mother, mother, there’s too many of you crying, brother, brother, brother, there’s far too many of you dying. You know we’ve got to find a way to bring some lovin’ here today.”

As Beatrice finishes the refrain by asking “What’s happening?” her ensemble of friends which include Hero (Margaret Odette), Margaret (Olivia Washington), and Ursula (Tiffany Denise Hobbs), sing the patriotic ballad “America the Beautiful” as a prayer and inspiration for the country to follow its ideals of “brotherhood from sea to shining sea.” This is not a war-like unction, it a solicitation for peace and goodness. Clearly, the women importune God to “shed His grace” on America. One infers their feeling as an imperative for political and social change hoped for, in a true democracy which can guarantee economic equality and justice.

The arrangement of “America the Beautiful” is lyrical and soulfully harmonious. As the women sing this anointed version they transform the text from hackneyed cliche, long abandoned by politicos and wealthy Federalist Society adherents, and uplift it with profound meaning. They encourage us toward authentically pursuing justice, brotherhood and unity in love and grace, elements which are sorely tried during the central focus of Much Ado About Nothing, during Hero’s unjust slander and infamy until she receives vindication.

(L to R): Chuck Cooper, Erik Laray Harvey in Much Ado About Nothing, by William Shakespeare, directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park, The Delacorte Theater, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

After the women finish singing, the men march in from the wars. Instead of arms, they carry protest signs decrying hate, uplifting love, proclaiming the right of democracy. Instead of a warlike manner they are calm. The theme of justice and the imperative for political and social brotherhood prayed for in the previous song is reaffirmed as we understand what the “soldiers” are fighting for. In Leon’s genius it is a spiritual warfare, a battle for the soul of American democracy. Leonato appreciates their endeavors and invites them to stay with him for one month to be refreshed and gain strength before they go back out for another skirmish against the forces of darkness.

The music and songs composed by Jason Michael Webb strategically unfold throughout the development of the primary love story between Leonato’s daughter, Hero (the superb Margaret Odette) and family friend Claudio (the excellent Jeremie Harris). And they follow to the conclusion with the funeral and redemption of Hero and her final marriage and dual wedding celebrations with the parallel love story between Beatrice and Benedick. The songs not only illustrate and solidify the themes of love, forgiveness, and the seasons of life, “a time for joy, a time for sorrow,” they unify the friends and family with hope and happiness through dancing and merriment. The melding of the music organically in the various scenes throughout the production is evocative, seamless and just grand.

(L to R): Margaret Odette, Jeremie Harris, Billy Eugene Jones, Chuck Cooper in William Shakespeare’s ‘Much Ado About Nothing,’ directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park (Joan Marcus)

After the men arrive from their protest, the director cleverly switches gears and the tone moves to one of playful humor and exuberance. With expert comic timing, Brooks’ Beatrice wags about Benedick in a war of sage wits and words. Coleman’s Benedick quips back to her with equal ferocity that belies both potentially have romantic feelings but must circle each other like well-matched competitors enjoying their “war” games as sport. They offer up the perfect foils to a plot their friends later devise using rumor to get Beatrice and Benedick to fall in love with each other in a twisted mix up that is hysterical in its revelations of human pride and ego.

The relationship between Beatrice (the marvelous Danielle Brooks) and Benedick (Grantham Coleman is her equally marvelous suitor and sparring partner) is portrayed with brilliance. The couple serves their delicious comedic fare with great good will and extraordinary fun. Their portrayals provide ballast and drive much of the forward action in the delightful plot events. Danielle Brooks gives a wondrously funny, soulfully witty portrayal. As Benedick, Grantham Coleman is Brooks’ partner in spontaneity, LOL humor, inventiveness and shimmering acuity.

(L to R): Danielle Brooks, Olivia Washington, Erik Laray Harvey, Chuck Cooper, Tiffany Denise Hobbs, Margaret Odette, William Shakespeare’s ‘Much Ado About Nothing,’ directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

Various interludes in Act I are also a time for male banter about the ladies Hero and Beatrice and the love match with Hero that friend of the family Don Pedro (Billy Eugene Jones) effects for his friend Claudio (Jeremie Harris). The scene between Benedick, Claudio and Don Pedro is superbly wrought with Benedick’s insistence he will remain a bachelor. The audience knows he “doth protest too much” for himself and for Claudio. The pacing of their taunts and jests is expertly rendered. The three actors draw out every bit of humor in Shakespeare’s characterizations.

Into this beauteous garden of delight, exuberance and order creeps the snake Don John (Hubert Point-Du Jour), brother of Don Pedro, and his confidante and friend Conrade (Khiry Walker). Though they support the fight for democracy, Don John is engaged in sub rosa familial warfare. We move from the macrocosm to the microcosm of the human heart which can be a place of extreme wickedness as it is with Don John who quarreled with his brother Don Pedro, his elder and does not forgive him. Don Pedro extended forgiveness and grace to Don John, which Don John feels forced to accept though he is not happy about it. Indeed, he is filled with rancor and seeks revenge, to abuse his brother and anyone near him, if the opportunity presents itself which it does.

(L to R): Danielle Brooks, Grantham Coleman in William Shakespeare’s ‘Much Ado About Nothing,’ directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park (Joan Marcus)

The conversation between Conrade and Don John is intriguing for what Shakespeare’s characterizations reveal about the human condition, forgiveness and remorse. Indeed, Don John is reprobate. Whether out of jealousy or the thought that he has done no wrong, he feels bullied to accept his brother’s public forgiveness. The theme “grace bestowed is not grace received unless there is true remorse,” is an important message highlighted by this production through the character of evil Don John who eschews grace. Indeed, extending grace and forgiveness to such individuals is a waste of time. No wonder Don John would rather “be a canker in a hedge than a rose in his grace.”

Trusting Conrade, Don John admits he is a plain-dealing villain. When he learns of Claudio’s marriage, he plots revenge on Don Pedro by attacking his best friend and smearing Hero’s integrity and fidelity to Claudio. The jealous Claudio is skeptical, but later “proof” during a duplicitous arrangement with an unwitting Margaret, Claudio becomes convinced that Hero is an unfaithful, unchaste philistine.

Lateefah Holder (center) and ensemble in William Shakespeare’s ‘Much Ado About Nothing,’ directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park (Joan Marcus)

Claudio’s jealous behavior and immaturity believing Don John turns goodness into another wickedness as evil begets evil. As they stand at the alter Claudio excoriates Hero as an unfit whore to the entire wedding party. Hero, injured unjustly by Don John’s wicked lie and Claudio’s extreme cruelty, collapses. In a classic historical repetition, once again misogyny raises its ugly head and condemns the innocent Hero destroying her once good name. Benedick, the uncanny Friar and Leonato stand with Hero. This key turning point in the production is wrought with great clarity by the actors so that the injustice is believable and it is shocking as injustice always is.

Thankfully, The Friar’s (a fine Tyrone Mitchell Henderson) suggestion to return Hero to grace and redemption in Claudio’s eyes by proclaiming her death to bring her again to a new life is effected with power. Finally, we appreciate a cleric who bestows love not condemnation or a rush to judgment! The emotional tenor of the scene is in perfect balance. Odette and Harris are heartfelt as is Cooper’s Leonato. The scene works in shifting the comedy to tragedy and of uplifting lies believed in as facts with wickedness overcoming love and light. Once again we are reminded that Shakespeare’s greatness is in his timelessness; that if allowed the opportunity for vengeance and evil, humanity will corruptly, wickedly use lies cast as facts to dupe and deceive the gullible, in this case Claudio.

(L to R): Grantham Coleman, Jeremie Harris, Margaret Odette, Danielle Brooks (center) ensemble, in William Shakespeare’s ‘Much Ado About Nothing,’ directed by Kenny Leon, Shakespeare in the Park (Joan Marcus)

I absolutely adore how the truth comes to light, through the lower classes represented by Dogberry (a hysterical Lateefah Holder) and her assistants who are witnesses to Don John’s accomplices to nefariousness. I also appreciate that all the villains in the work admit their wrongdoing; it is a marvel which doesn’t always occur the higher the ladder of power and ambition one ascends. But this is a comedy with tragic elements, thus, evil is turned to the light and Beatrice and Benedick the principle conveyors of humor are lightening strokes of genius which soothe us to patience until justice arrives right on time.

I also was thrilled to see that the remorseful, apologetic Claudio willingly accepts Hero’s recompense (Leon has Hero dog him in the face) as she unleashes her rage at his unjust treatment. These scenes of redemption and reconciliation ring with authenticity: Cooper, Odette and Harris shine.

The celebrations, masked dance, marriage between Hero and Claudio, Hero’s funeral and the final marriages are staged with exceptional interest and flow; they reveal that each in the ensemble is a key player in the action. The choreography by Camille A. Brown and the fight direction by Thomas Schall are standouts. Kudos also goes to those in the creative team not previously mentioned. Peter Kaczorowski’s gorgeous lighting design conveys romance and subtly of focus during the side scenes; Jessica Paz’s sound design is right on (I heard every word) and Mia Neal for the beautiful wigs, hair and makeup design receives my praise.

Leon’s Much Ado About Nothing is one for the ages. It leaves us with the men doing warfare for the soul of democracy leaving Leonato’s ordered world of right vs. wrong where the right prevails. Once again soldiers fight the good fight and go out to resist and stand against the world of “alternate facts” where chaos, anarchy, and the overthrown rule of law abide (at this point) with impunity. Leon counsels hope and humor; progress does happen, if slowly.

This production’s greatness is in how the director and cast extract immutable themes. These serve as a beacon to guide us through times that “try our souls,” and they encourage us to persist despite the dark impulses of money-driven power dynamics and fascist hegemony that would keep us enthralled.

I saw Much Ado About Nothing in a near downpour then fitful stop and start to continual light rain during which no one in the audience left. Despite this the actors were anointed, phenomenal! I would love to see this work again. I do hope it is recorded somewhere. It’s just wow. The show runs until June 23rd. You may luck out with tickets at their lottery. Go to their website by CLICKING HERE.

‘American Son,’ on Broadway, Starring Kelly Washington, Steven Pasquale

Steven Pasquale, Kerry Washington, ‘American Son,’ directed by Kenny Leon, written by Christopher Demos-Brown (Peter Cunningham)

American Son written by Christopher Demos-Brown is a much needed polemic about what happens to young black males in our nation. If you can help it, don’t be a young, black male. Or if you are, try to stay off the streets between the ages of 13-35. Then, your chances of being shot or incarcerated should be greatly reduced.

To what extent does law enforcement abuse figure in to the above? The percentages speak for themselves. Indeed, this is especially so if one considers that law enforcement regulations and gun laws vary from state to state. However, do not take my word or this production’s thematic pronouncements at face value. Read the crime blotters in cities and suburbs. Sadly, the facts/statistics mount up. And this “in-your-face,” “no-holds-barred” drama powerfully directed by Kenny Leon, presents a typical case so we cannot blink or turn away. Nor can we pretend American Son lays out a mostly fictional reality. If only that were true.

The title generalizes to all our American sons. It does this in the hope that we empathize and understand especially if we are white. Eventually, our nation may become color blind, and there will be no need for the paranoia of white supremacy, Neo-Nazis, and the KKK. Then we will have achieved a miracle of decency and humanity. Surely, then law enforcement will not be partisan to favor white males over women and darker hued men and women of all races in the apprehension of suspects. Perhaps then we will be able to uplift the United States as a country which stands for equal opportunity and justice for everyone. Until then, our presentments express nobility, but our actions express venality and injustice.

Having taught in a multi-cultural district for decades, I’ve known of tensions between law enforcement and various cultures. I can think of one incident when a male student as talented and erudite as Jamal (Kendra’s son in American Son), discussed his experience of police brutality. I saw the remnants of the beating on his handsome face and was sick for the trauma he went through. Thankfully, since then he has prospered in his life and has his own family.

That was over twenty years ago. Overall, the situation has worsened. The rhetoric has escalated, and groups which work to ameliorate the tensions between law enforcement and various cultures have faltered. Often conservative, right-wing, partisan think tanks hold up memes of such groups as fodder for their smear campaigns. They promote antipathy to accelerate their political agendas against gun control and in support of oligarchic nationalism. Also, they seek to divide the populace and incite incidents throwing law enforcement in the middle of the fray.

(L to R): Kerry Washington, Steven Pasquale, Jeremy Jordan, ‘American Son,’ written by Christopher Demos-Brown, directed by Kenny Leon (Peter Cunningham)

And what of law enforcement representatives of multi-cultural groups? Indeed, circumstances squeeze them to an “either-or” choice between a rock and a hard place. Few issues have a thesis-antithesis result or solution but remain extremely complex. Thus, the lack of will and incomplete measures to solve problems remain beyond the grasp of well meaning individuals.

All of these issues and many more Demos-Brown presents in this soul-crushing drama that reminds us we live in a nation whose values allegedly proclaim equality for all. But whose recent government practices establish equality for the rich, privileged and predominately white conservatives. Living in the South, even if the city is Miami, the setting of American Son, if a son is not a white, young male, but a black male, then black mothers’ anxiety living in that culture increases. Sadly, their fears for their son when encountering police often is warranted.

African American parents understand that their son’s age and skin-color provide a tragic liability for harm. Darkly hued skin colors arrest faster than white skin colors. Driving while black used to be a twisted joke. You know, when a black male drives through a white neighborhood, he is there to commit a crime. The situation has been exacerbated and the joke has morphed. Now, if one is riding while black, walking while black, smiling while black, hanging out while black, existing while black, one becomes a police suspect.

The question remains. To what extent have members of law enforcement across the nation lost their moral compass about civil rights? And how has the “use of force” taken on sinister tones toward people of color in the aftermath of protests concerning Michael Brown, Travyon Martin, Sandra Bland, and many others?

As Kendra (Kerry Washington is magnificent throughout), Jamal’s mom suggests, if you’re not black you will not understand the fear of a mother for a child who is missing. And she vehemently asserts this truth to Jeremy Jordan’s Officer Paul Larkin who tries to ameliorate her vocal volume and push back as to his whereabouts. Larkin, the white police officer manning the midnight shift in the law enforcement building where Kendra waits for news of Jamal, appears to be a fine person.