Blog Archives

‘The Queen of Versailles,’ Fabulous Kristin Chenoweth Makes Dreams Realities

If the road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom (quote by English poet William Blake), do people know when they’ve reached their limit? When is enough enough? According to the themes of the new musical The Queen of Versailles, currently at the St. James Theatre, knowing this depends upon the seeker.

In the clever, sardonic musical, based on Lauren Greenfield’s titular documentary film and the life stories of Jackie and David Siegel, the question of excess and how to measure it shines into the darkness of American culture, conspicuous consumption, surgically enhanced, plastic looks, and meretricious values. With an ironic, humorous, no holds barred book by Lindsey Ferrentino, and music and lyrics by Stephen Schhwartz, the Siegel’s riches to more riches story, including the 2008 mortgage debacle, takes center stage. By the conclusion, the audience leaves shaken and maybe stirred, either with a bad taste in their mouths or with the prick of guilt in their consciences.

At its finest, The Queen of Versailles inspires the audience to peer into their own values and behavior and evaluate their souls to correct. Ultimately, it asks, do the Siegels have a worthwhile life or have they allowed their childhood poverty to overwhelm their good sense and inner emotional well being? Despite its ripe fun Ferrentino’s book and Schwartz’s music encourage a hard look at crass, materialistic greed that blinds the rich from using their largess for the social good. Lastly, it questions do the representative Siegels count the cost to live the oversized billionaire’s lifestyle which causes harm? To what extent has their craven indulgence choked off their lifeblood to their own destruction?

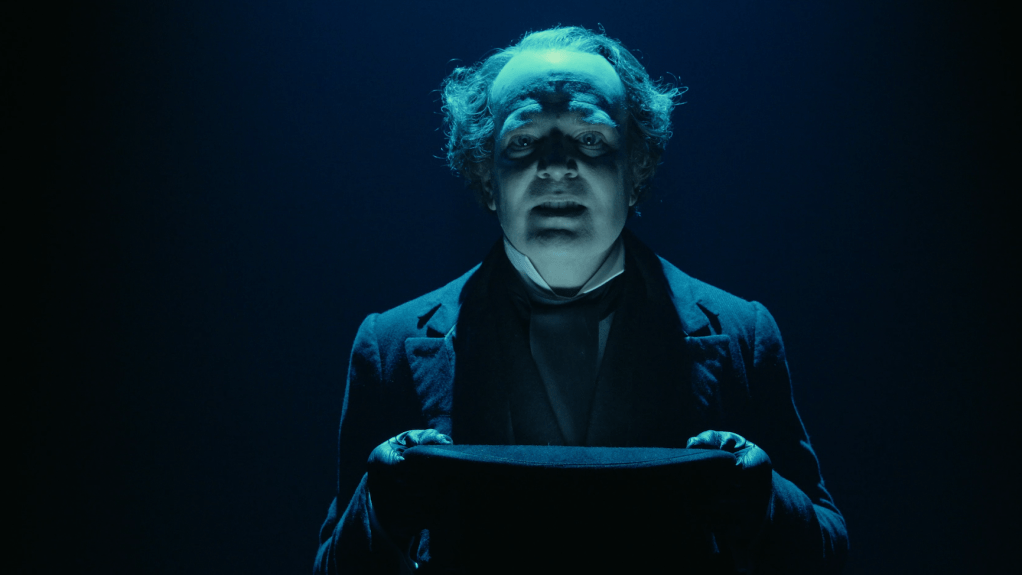

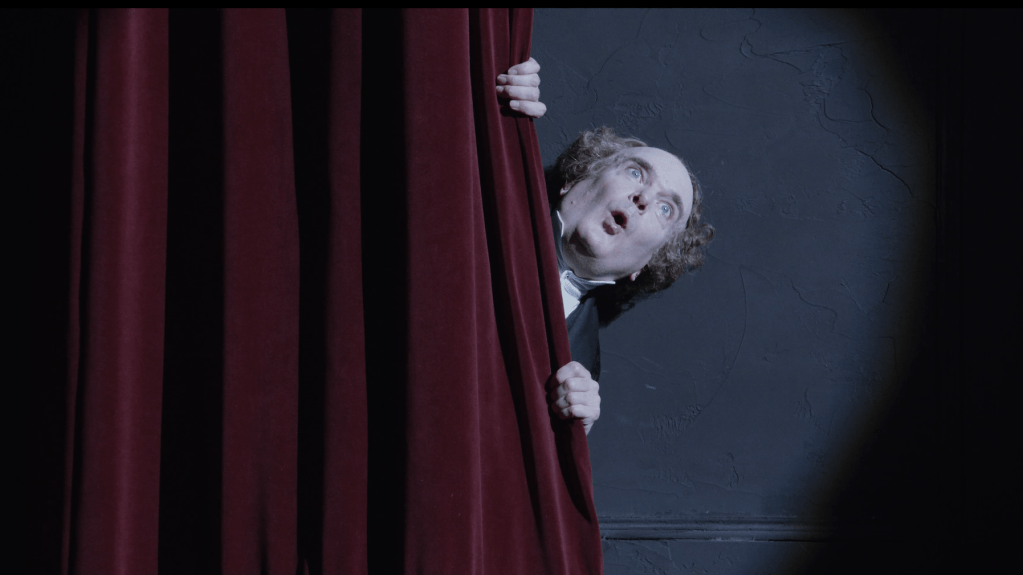

Starring an endearing, heartfelt and bubbly Kristin Chenoweth as the materially insatiable Jackie Siegel, and F. Murray Abraham as billionaire workaholic David Siegel, the New York premiere which has an end date of March 29, 2026, rings with disturbing truths. It’s farcical, dark elements present many themes. Chief among them is the theme that the Siegel’s shiny ostentation hides a sad emptiness that can never be fulfilled.

Framing the Siegel’s story with the key meme of Versailles, the mansion in France that 17th century Louis XIV, built as a memorial to his majesty, the opening scene and song (Pablo David Laucerica is King Louis XIV) replete with period chandeliers, furniture, costumed butlers and maids reveals how and why the Sun King built his palace on swampland (“Because I Can”). Without giving thought to the inequities in French society that necessitated the economic gap between royalty and its impoverished, destitute subjects, Jackie and David want one.

In a quick switch to the present (2006) we see the Siegel’s Versailles in progress. With construction scaffolding in the background and a documentary film crew in the foreground, Chenoweth’s Jackie glows as she sings “we want to have the very best for the biggest home in America because we can.” The fluid set design with appropriate props and pieces by Dane Laffrey, who also does the video design, brings perfect coherence to the Siegel’s intentions. It connects the idea of royal wealth manifest in Louis XIV’s lavish excess to their rich/famous lifestyle which reeks of tawdriness. Thanks to Michael Arden’s staging and direction and Cristian Cowan’s costumes, and Cookie Jordan’s hair and wig design, the shifts from the present to the court of Louis XIV and back solidly establish the trenchant themes of this profoundly current musical.

Presuming themselves American royalty, the Siegels hope to replicate a modern-day Versailles, like their mentor king. Indeed, they will best him. Their Versailles has whatever the family wants. This includes a jewelry-grade gem stone floor, an in-house Benihana (with all those tossed shrimp because David doesn’t like to stand on line), a spa, a pool with a stained glass roof, and a family wing with numerous bedrooms and bathrooms so Jackie doesn’t lose track of her seven kids.

After this opening salvo that mesmerizes like any show about the “lifestyles of the rich and presumptuous,” we discover that Jackie didn’t always come from wealth. In fact her story mirrors the old Horatio Alger “rags-to-riches” fable that Alger shaped into the American Dream, which abides today and which also influenced F. Scott Fitzgerald’s take on it in The Great Gatsby. Jackie, albeit a female dreamer, buys into the concept that if she pulls herself up with determination, works hard and does good works, she can lift herself into the upper classes.

We see how this manifests in the next segment of Chenoweth’s 17-year-old version of Jackie with her parents Debbie (Isabel Keating) and John (Stephen DeRosa) in their humble Endwell, New York home. Debbie and John count on Jackie to continue to work as many jobs as possible to become rich and famous like the titular show they watch together. Singing the song “Caviar Dreams,” a ballad that expresses beautifully a female Alger hero, we “get” Jackie’s drive and pluck to work day and night to achieve an engineering degree at IBM, then kick the job to the curb because it won’t give her wealth fast enough.

As she “keeps on thrustin” she makes a bold turn into marriage with alleged banker Ron (Michael McCorry Rose), who disappoints when he drags her to the Everglades, and opposes her Mrs. Florida win. When he physically abuses her, despite her pregnancy, Jackie leaves. Singing “Each and Every Day” beginning when Victoria is a baby, the scene switches to the present at the construction site and the teenage Victoria (the excellent Nina White) enters. Chenoweth’s Jackie soulfully finishes the song to Victoria in an important transitional moment. We understand Jackie as a survivor who loves her firstborn, who she claims saved her life.

Not only does Jackie not look back, we learn she and baby Victoria lived in an apartment which “barely fit the baby’s crib and Jackie’s sleeping bag.” However, always “thrustin’ forward,” she recognizes opportunity when she goes to a party where she meets David Siegel, the CEO of Westgate Resorts. As it turns out, his impoverished childhood was similar to hers and left him with dreams of extreme wealth. F. Murray Abraham does justice to David throughout, first as a “cowboy” in the wild west of timeshares as son Gary (the fine Greg Hildreth) sings with the ensemble “The Ballad of the Timeshare King.” Occasionally, for emphasis, Abraham’s David chimes in with irony.

For example, David’s sales force make “one hundred percent of their sales on the first day.” Gary sings, “George W.’s president now, thanks to David Siegel.” When folks can’t afford the timeshare, Siegel helps them with financing from his bank, so the ensemble sings joyfully, “Yippee-I-owe-you-owe-we-owe.” We recognize the sardonic humor for David’s dishing out sub-prime mortgages to “anyone who breathes.” Of course this adds to the mortgage crises of 2008 which taxpayers foot the bill for. Eventually, the sub-prime loans bring his empire to the brink of bankruptcy as the crash swallows whole billionaires like David.

At that point, Jackie and David have been married with children and are two years into the Versailles construction having cycled through songs of their outsized wedding (“Trust Me”), a honeymoon trip to Versailles bringing back a scene of King Louis XIV and his courtiers. Smartly, Ferrentino and Schwartz reinforce their themes by joining past and present in the reprise “Because I Can and the “Golden Hour.”

However, conflict looms on the horizon. Though David and Jackie live their wildest dreams and birth child after child, daughter Victoria feels miserable, insular and ugly. “I know mom wishes I was prettier,” she sings in the poignant “Pretty Wins.” And in Act II in the superb “Book of Random” Victoria sings from her journal, the thoughts that she keeps hidden. Unlike her mother Victoria grounds herself in her current feelings of sadness brought on by reality, escapism fueled by drug addiction and scorn for their damaging and excessive lifestyle. However, when Jackie’s niece Jonquil (Tatum Grace Hopkins) arrives and Jackie takes her in, we think that Victoria has someone to confide in.

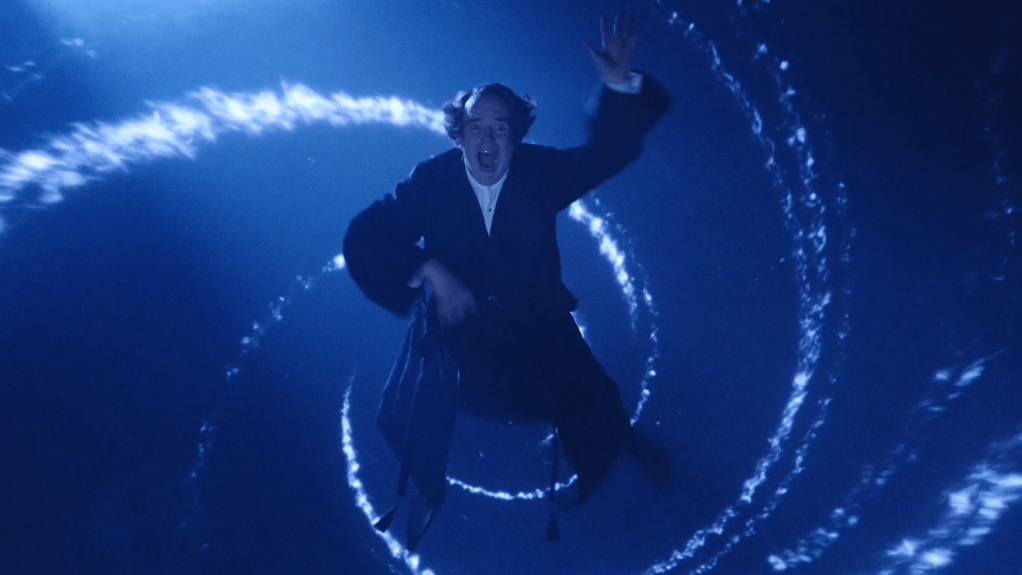

But Jonquil doesn’t understand Victoria’s dislike of Jackie’s appetite for more. And it doesn’t help Victoria that Jonquil becomes a clone of Jackie (“I Could Get Used to This.”). Ironically, when the crash happens and Victoria hears of the talk that they will sell Versailles to keep David from going belly up, she feels relief. In a farce-filled scene in the 17th century Versailles, with some of the most ironic lyrics, the Sun King chides the Siegels and Americans in the song “Crash.” “You thought you’d be egalitarian, let peasants own their own homes in some altruistic plan. Well, what were you expecting from a choice so rash? Crash…”

At the end of Act I, we have only Jackie’s spunk and perseverance (“This is Not the Way”), and David’s connections to rely on to bail them out of bankruptcy and foreclosure. Act II reveals that deus ex machina saves them when the government (taxpayers) bail out billionaires and banks. Naturally, the little people with no safety net lose their shirts. Where the peasants of France revolted against their royals (there is a humorous scene with the luckless Marie Antoinette on her way to the guillotine), in America, no one goes to jail because the banks and firms are “too big to fail.”

At the end of Act II, in a scene with King Louis XIV, in a reprise of “Crash,” King Louis and his courtiers sing as Marie Antoinette says “goodbye.” Here, Schwartz’s lyrics and tune underscore a crucial theme. America’s Aristocracy has cleverly worked it out that “democracy” will prevent revolutions. How? The rich have peasants “thinking they’re tomorrow’s millionaires; that you’re special privileges will someday soon be theirs.” And the ensemble adds, “No blade across the throat for you. Instead it seems your peasant class will all turn out to vote for you!” Thus, with no accountability for wrecking the economy and countless lives, the rich get richer, and Jackie and David, out of bankruptcy, continue building Versailles.

However, in all of the mayhem of trying to regain solvency, the Siegels sacrifice a family member. If material empires go on for centuries, flesh and blood does not. The unreality of excess belies mortality. But some folks never learn. Schwartz and Ferrentino ironically underscore this as Chenoweth’s Jackie holds a glass of champagne standing in front of a ring light. She speaks to a social media audience and hopes that, like her, they get their “champagne wishes and caviar dreams.”

The Queen of Versailles runs 2 hours 40 minutes with one intermission at the St. James Theatre. https://queenofversaillesmusical.com/

‘Maybe Happy Ending,’ Breathtaking With Darren Criss, Helen J Shen

Maybe Happy Ending

“Memento Mori!” The Stoics created this phrase meaning “remember you must die.” Human beings can be incredibly oblivious to their own mortality, especially when they are young. Indeed, it gets worse as one ages in the attempt to forestall looking old to remain “forever young.” But what does that have to do with robots Oliver (Darren Criss) and Claire (Helen J Shen), simulated, digital human beings who run on technological parts and have operating systems, batteries, chargers, chips, etc.? As it turns out “memento mori” is the linchpin of Maybe Happy Ending, currently at the Belasco Theatre until January 2026.

As with all things, even with long-lived elements like tellurium-128, the second law of thermodynamics applies: all things move from order to chaos, entropy. Heat dissipates into cold. Things fall apart. Things come to an end. It’s irrevocable. And at this point there’s not a damn thing one can do but live life to the fullest, if memento mori..

It is Claire, an advanced Model 5 robot, who is sleek, beautiful, witty and programmed to understand most things, who essentially reminds Oliver that things come to an end.

But Oliver doesn’t really get it. Oliver is a less smoothly functioning and quirky-kinky-glitchy robot Model 3. The earlier, older model is more simplistic and durable, programmed to be upbeat, decorous, sweet. He is the perfect companion, friend, son, but unaware about the deeper, more painful qualities and attributes of human beings and the natural order of the known world and his place in it. Innocent, and cheerful, he doesn’t seem to understand the cycles of wheel and woe, peaks and valleys and the end of things, for example humans, relationships, devices, himself. But by the conclusion of this incredible heart-rending musical, Oliver learns about himself. He learns what he is capable of, guided by Claire’s empathy, wisdom and heart.

The year is 2064 on the outskirts of Seoul, Korea when we meet Oliver and Claire, Helperbots (think android servants), once hired out by their manufacturer to assist their human owners with daily tasks. However, a blip has occurred for Oliver and Claire whose existence and purpose has changed. Their antiquated operating systems can no longer be upgraded. Replacement parts are scarce or discontinued. The company has with consideration allowed them to spend their purposeless, remaining days in a retirement home in the Helperbot Yards until they come to the end of themselves.

The set design of their rooms at the Helperbot Yards is imagined cleverly by Dane Laffrey via bright lighting in their rooms (Ben Stanton’s design), surrounded by darkness. Neon tube sliding panels separate and feature Claire’s and Oliver’s rooms side by side, or in movement, like a split screen effect. The rooms are color coordinated. Claire’s belongings are pink and lavender with saturated lighting effects. Oliver’s room appointments are mostly neutral influenced by his owner with blue lighting effects. The colors ironically signify their genders, recalling an innocence that belies their knowledge and Claire’s deeper understanding of human beings. As they grow closer, the saturated lighting effects sometimes alternate.

Laffrey’s scenic and additional video design, along with Ben Stanton’s lighting design and George Reeve’s video design cohere perfectly with director Michael Arden’s vision and tone, effected by Hue Park’s book and lyrics and Will Aronson’s book, lyrics and music, which is sonorous, mellifluous and lovely.

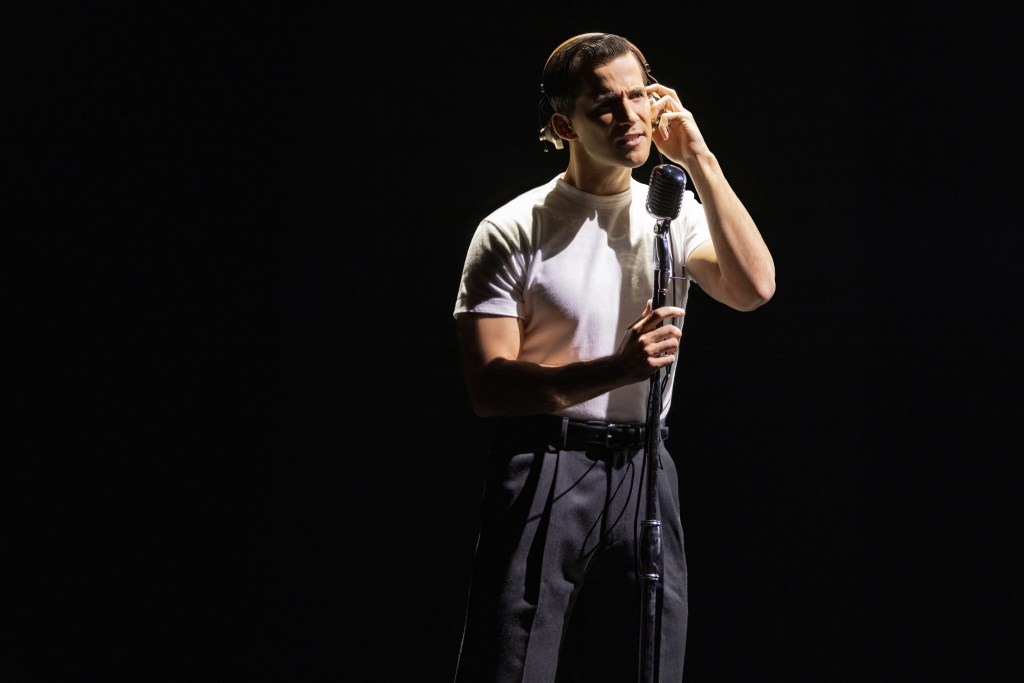

Oliver appears Model 3 robotic with slicked down helmet-headed hair, (Craig Franklin Miller’s hair & wig design), obvious reddish lips and paste skin tone (Suki Tsujimoto) and a perfectly tailored, boyish outfit by Clint Ramos. Claire’s pleated skirt and white blouse are simple, and flowing in more natural colors as the later models were designed to appear real; her hair and make-up coordinate and appear natural. The vibrant color and Ramos’ costumes cohere with the color schemes, save Claire’s initial outfit, though she wears a colorful jacket when they travel.

The design features represent the robotic and real worlds stylized appropriately. The real world is dimly lit and in shadow; the natural setting is somber, subdued and minimal. There is no sense of futuristic design consonant with James’ preference of retro mirrored in his acoustic music taste. James and his son (both played by Marcus Choi) naturally. Likewise, singer Gil Brentley appears in fall toned period clothing of the 50s. Sometimes with a microphone, perhaps in a club where he once performed, Brentley sings four songs solo in simple lighting. Finally, the forest scene is magically lit, captivatingly stylized, romantic and “to die for,” which is the point.

Peter Hylenski’s sound design is balanced for Deborah Abramson (music supervision), and the songs are lyrical, the harmonies in the duets gorgeous. Both Criss and Shen have voices that convey the tone of light, love and beauty. The cool jazz numbers sung by the excellent Dez Duron as singer Gil Brentley are seamlessly mixed into the action as a counterpoint to it and commentary on it.

Of the two robots, Shen’s astute, ironic Claire is the more aware, having experienced poignant and hurtful events with her beloved owner who gave her up. We get to see this via amazing digital projections and a hologram (George Reeve’s video design), as Claire revisits memories to fill in the puzzle pieces of a mystery Oliver needs to have solved. Claire is canny, smoothly sophisticated and not easily duped. There is little that she can’t figure out. On the other hand, Oliver is oblivious about why he is where he is. Oliver believes that his beloved owner and friend James will be coming to take him to wherever he has gone so they may resume their relationship which makes both of them happy.

With Oliver’s first song, “World Within my Room,” Will Aronson and Hue Park establish the situation of his isolated living arrangement which he doesn’t mind, convinced James will come for him. He is contented in his own confined world with his friend, the plant HwaBoon, his jazz records, an old-fashioned record player, all given to him by James, a jazz aficionado who converted Oliver to love jazz too. Indeed, Oliver gets to enjoy monthly jazz magazines James has sent to him which Oliver receives via a mail chute. His only interaction over the years is a remote bot (a voice over), that interacts with him if he requests something i.e. a replacement part that has not yet been discontinued.

Twelve years go by, then there is an urgent knock that displaces Oliver and his contented isolation. Claire, who lives across the hall, needs a charge because the advanced Model 5s need charging more frequently or they freeze up, as Claire does, arm lifted in the midst of knocking. Oliver is too jarred by a live interaction intruding on his solipsistic existence to immediately answer the door. When he finally does relent, she is stationary, silent, frozen, and he must pick her up and carry her into his room to charge her up (literally and figuratively). Look for all of the double entendres, sly, winking humor, symbolism and metaphors about human existence, human love, human experience and forever love and happiness.

After Oliver “charges” Claire, she takes the lead, as the female model’s advanced assertiveness prompts her to. She queries him, and finding out about James, understands what has happened, but is empathetic enough to wisely counsel Oliver, sometimes with humorous snark about himself. Additionally, she dispels the competitiveness Oliver has about being the less sleek, smart and advanced model. However, she is less durable, a fault he continually throws in her face. Eventually, as Claire repeatedly returns to borrow his charger, one day she cleverly arranges to stop their routine, knowing the less flexible Oliver will freak out about it. Of course, she is correct, and when he begins to seek her out, their relationship faces a turning point and they are off and running to become more involved with each other’s wants, needs and hopes.

Claire and Oliver’s growing connection is a series of cataclysmic sequences that explode upon the audience’s consciousness. These are taken out of every romantic playbook of “boy meets girl” etc. However, it’s in reversal as Claire is the catalyst. Importantly, there is no equivalence because these robots can’t have emotions, can they? They’re weird, the situation is anomalous, but for the song (“Why Love?”) as a lyrical remembrance at the top of the musical, we don’t quite get it. We think, “OK, theirs is a peculiar and funny meet-up.” Importantly, though they look youthful, they are “discontinued,” seniors in a retirement home, useless, waiting to fall apart (think of “all the lonely people” whether in nursing homes or under sick-bed isolation).

Eventually, the realization hits the audience that they are looking at themselves. There will be an arrow strike into the heart and perhaps the tears or the discomfort will follow, if not at earlier junctures, yet, it will follow. The story and its incredibly coherent, metaphoric rendering in every technical and live-wired aspect (especially performances), by the creatives are designed to penetrate any cynical, hardened emotions and break your heart.

The parallel between Claire and Oliver’s story and variations of our own stings as does the song “Why Love?” sung gorgeously by Duron’s Gil Brantley. The song that James loved (he gave the Gil Brantley record to Oliver), opens the musical and concludes it, a question answering with the question. And we learn its meaning as we know it from our own lives and the journey of Claire and Oliver, as they get to know each other. The irony of these characters and their discoveries about themselves and each other is that we will more readily identify precisely because they are robots. By removing their “humanity,” the intensity of the parallels to human experience crystallizes. You “get it” in revelation, and by then, you are a goner.

Michael Arden’s shepherding of Criss and Shen ingeniously unfolds and stages their relationship dynamic throughout, moving from their box-like, enclosed, limited existence to a forest field, in a nighttime sky of fireflies (an achingly beautiful sequence lit exquisitely by Ben Stanton). Enlightened from their adventurous “road trip,” they go back home with a new, expansive perspective and realization of their deep connection to each other, a duplication of human experience which they can laugh at as robots, yet sorrow over, for it, and they are perishable.

The characters and situation are counterintuitive as are the incredible performances of Criss as the more authentically robotic and Shen’s more progressively human. But by the conclusion both have evolved to decide whether to remember their love or not, knowing there is no way around the second law of thermodynamics. Even robots die. But in this instance, the more durable Oliver will be around with the memories of their love a lot longer than Claire. A decision must be made.

Maybe Happy Ending is not a story about robot love. It is a story about us. Our humanity. Our mortality. Our inability to comprehend loss, and love, and relationships, and other human beings, and emotional pain, and hurt, and tolerance of these experiences, not having the first clue about what they truly are, as we are forced to go through them, sometimes kicking and screaming

If you don’t see Maybe Happy Ending, you are missing an incredible, theatrical event, taking a deep dive into your own humanity through identification with “robots” who just kill it. They will delight, entertain and wreck you emotionally. If that doesn’t appeal, then see it to appreciate its splendiferousness as a gobsmacking, award winning, uniquely, amazing musical.

Maybe Happy Ending runs 1 hour, 45 minutes with no intermission at the Belasco Theatre (111 West 44th Street) until January 2026. https://www.maybehappyending.com/

ENCHANTING, SPELLBINDING, HEART-STOPPING, MOVING, TOUCHING, OVERWHELMING, INTENSE, HEART-RENDING

Maybe Happy Ending runs with no intermission 1 hours 45 minutes. at the Belasco Theatre (131 West 44th Street). https://www.maybehappyending.com/