Blog Archives

‘Mother Play,’ Stellar Performances by Celia Keenan-Bolger, Jessica Lange, Jim Parsons

One of the keys to understanding Mother Play, A Play in Five Evictions by Paula Vogel is in the narration. Currently running in its premiere at 2NDSTAGE, directed by Tina Landau, Vogel’s play has some elements of her own life, but is not naturalistic. It is stylized, quirky, humorous, imaginative and figurative, like most of her plays. In a nod to Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, in the notes, she suggests it is a memory play.

Presumably, the play focuses on a representative mother, Phyllis, portrayed with impeccable sensitivity, raw emotion and nuanced undercurrents of bitterness, humor and irony by the exceptional Jessica Lange. However, the play is actually about a mother-daughter relationship that moves toward reconciliation. As such, the narrator/daughter (the always superb Celia Kennan-Bolger), directs us to her understanding of the last forty years of her life in her relationship with her mother, via the unreliable narrator’s viewpoint.

Should we believe everything the narrator says happened? Or does Martha’s perception of her mother cling to highlights of the events most hurtful and damaging to her? We must ultimately decide or remain uncertain until the play’s conclusion. It’s a delicious conundrum that emphasizes Vogel’s themes of the necessity of developing a deeper understanding of relationships, emotional pain, working through hurt and so much more.

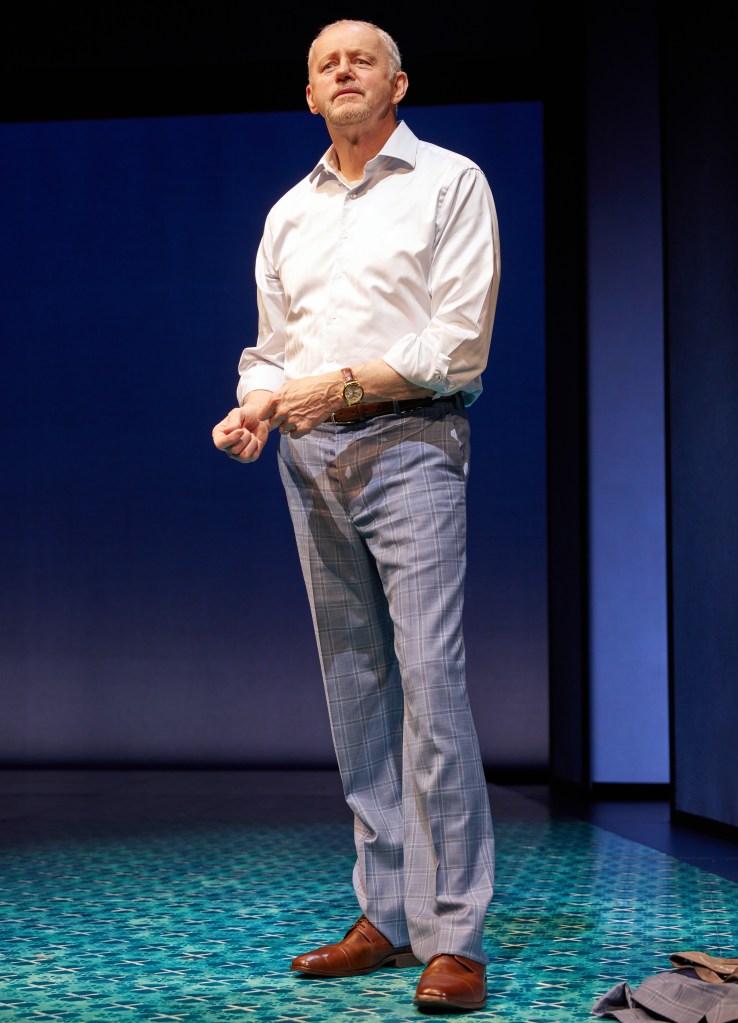

Martha’s genius gains our confidence, empathy and identification with her confessional re-enactment flashbacks as she remembers events. She takes us through the highs and lows of five evictions her family experiences together, after their father dumped them for greener pastures. A key figure in the family dynamic is her two-years older brother Carl, Martha’s brilliant, sweet and kind protector, portrayed with clarity, humor and depth by Jim Parsons.

At the top of the play, which is in the present, Martha is in her early 50s. She tells us that by the time she was 11, their family had moved seven times because their father had a “habit of not paying rent.” Thus, they learned to pack and unpack in a day. She comments with irony that there is a season for packing and a season for unpacking, referencing the Biblical verse (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8), and the Byrd’s song, “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

To destabilize and uproot children from their friends and school mates so many times is a calculation Vogel’s Martha never makes. But it speaks volumes about how the brother and sister rely on each other emotionally, because they are social isolates by necessity because the continued movement which their father, whom we only hear about, didn’t even take into consideration.

As Martha opens a box of the only things her deceased brother had left in their apartment, she takes out a bunny rabbit and a letter Carl had written to her. With the letter, Parson’s Carl materializes and Martha joins him as they step into a series of flashbacks which chronicle events that lead to the five times they were evicted by landlords or they evicted themselves from each other’s lives, only to return, eventually.

Cleverly grounding this family’s living arrangements to present her salient themes about “forever pain,” the impossibility of “mothering,” sacrifice, regret and love, Vogel uses two devices. The first is their furniture which they take with them and rearrange each time they pick up and take off for various reasons. Secondly, there are the roaches, which are magical and symbolic, not only of the poverty and want their father stuck them with, but of the emotional terror and fear of living precariously on the edge of society, sanity and Phyllis’ desire for normalcy.

The roaches, at key moments manifest, swarm, go creepy crawly and loom monstrously in their lives. Since Phyllis signs leases to cheaper basement apartments, promising they will take out the garbage, they are forced to live with these vermin, an indignity of representative squalor from which they never seem to be freed, despite upwardly mobile Phyllis’ attempts to rise to apartments on higher floors.

The first flashback occurs when Martha is twelve, Carl is fourteen, and Phyllis is thirty-seven, in their first apartment away from their father after the divorce. Carl and Martha arrange the furniture and when they are finished, they swivel around Phyllis, reclining in an easy chair in Landau’s deft, humorous introduction of the women the play is allegedly about. Far from “taking it easy,” Lange’s Phyllis demonstrates she is “on edge” and seeks to quell her nerves at this first move without her husband. She immediately importunes her children for the following: her cigarette lighter (a gift from “the only one she loved”), a glass for the gin which she carries in a bottle in her large handbag, and ice, ready made in a tray in a box. After pouring herself a drink and puffing on her cigarette, she begins to relax and says, “Maybe mother will be able to get through this.”

Ironically, the “this” has profound, layered meaning not only for the moment, but for what is ahead for Phyllis, including single parenting, a possible nervous breakdown, poverty, responsibility as a mother, her job and more.

Phyllis pulls out their dinner in a McDonald’s bag from her bottomless black purse, which is empty of money because their father wiped out all the accounts. She speaks of their future-Martha cooking, cleaning and getting dinner, and Carl continuing his excellence of a near perfect score on the PSATs in verbal skills. Phyllis predicts Carl will be the first one in the family to get into college via a scholarship. Martha will take typing and get a job like her mother, so that if a man leaves her like her father discarded her mother, she will be able to support herself.

Though Carl quips flamboyantly about affording rent at the Algonquin, Martha sours at having to share a bedroom with her mother who snores. The favored one, Carl gets his own room. With their new beginning as latch key kids, who have to make their own lunches and deal with their own problems, toward the end of the segment, Carl humorously asks Martha if their childhood has ended.

Being a breadwinner and sole parent is a circumstance Phyllis bitterly resents. Culturally, moms still stayed at home, cooked, cleaned, did the laundry, took care of all the needs of the children, attended to them before and after school, and bowed to their husbands, who had the freedom to do what they pleased, expecting dinner at whatever hour they returned to a wife thrilled to see them. It is this “achievement” that Phyllis wishes for Martha, whom she hopes will marry someone unlike Mr. Herman, in other words a bland man who is unappealing to women and just wants a loyal wife like Martha will be because Phyllis has raised her to be the good woman.

Though Phyllis proudly proclaims this new apartment is a step in the right direction, Phyllis cannot “move on” to annihilate memories of her husband’s past physical and financial abuse, his scurrilous behavior, his machismo insisting all is his way. Filled with regret, Phyllis lapses into negative ruminations about their father who doesn’t provide child support or come to visit. Her cryptic remarks, sarcasm and “treatment” of Martha and Carl, who she openly praises and admires, while being “hard” on Martha, so she won’t marry a fraud, is sometimes humorous, but mostly unjust. In the telling Martha has our sympathy against this cruel, anti-nurturing mother.

Ultimately, we learn that each time they move for a reason that triggers them, each time they pack and unpack and arrange the furniture to settle in, they are still stuck in the same place emotionally because Phyllis can’t forget, forgive or release her anger. And though she adjusts as best she can, she relies emotionally on Carl and Martha, who she eventually evicts when she discovers they live a lifestyle that disgusts her and shatters her dreams for them.

Sprinkled throughout the five evictions and events leading up to them is Vogel’s humor and irony which saves the play from falling into droll repetitiveness because emotionally Phyllis’ needle is stuck in the same groove. Her emotionalism worsens as key revelations spill out about who she is as a woman, who once was adored by the same man who left her for “whores.” Throughout the sometimes humorous, sometimes tragic and upsetting events, Carl and Martha continue to serve and wait on Phyllis until they reach their tipping point. Overcoming these painful events with their mother because they have each other, Carl continues to guide and counsel Martha as a loving brother. This becomes all the more poignant when he leaves the family for various reasons, the last one being the most devastating for Martha and Phyllis.

Landau’s direction and vision for this family whose dysfunction is driven by internal soul damage shared and spread around is acutely realized. The following creatives enhance her vision: David Zinn’s scenic design of movable furniture, Shawn Duan’s projection design of interminable roach swarms, Jen Schriever’s ethereal, atmospheric lighting design (when Carl appears and disappears in Martha’s imagination), and Jill BC Du Boff’s sound design (I heard every word).

Landau’s staging and shepherding of the actors yields tremendous performances. Lange’s is a tour de force, encouraged by Parsons and Keenan-Bloger, whose development through the years pinging the ages from Martha’s 12 years-old and Carl’s 14-years old through to Martha’s fifties is stunning. Parson moderates his maturity and calmness as a contrast to the dire events that occur in the play’s last scenes. The disco scene is amazingly hopeful until Phyllis breaks emotionally and spews fearful, hurtful words.

Always, Keenan-Bolger’s Martha remains ironic, rational, questioning, matter-of-fact. Lange’s fragility and vulnerability underlying her outbursts prompt the stoic response from Parsons and Keenan-Bolger, whose Carl and Martha often take the role of the adults in the room. After a while, Martha has so blinded us to her portrait of Phyllis, we believe her hook, line and sinker that Phyllis is a b*&ch.

Phyllis’ deterioration into heartbreaking loneliness as her children remain estranged from her is attempted by Vogel in a scene that may have been shortened or should have been realized differently, or should have included different tasks by Lange’s Phyllis. Phyllis attempts to moderate her drinking alone in the evening at a time when women get drunk as evening alcoholics. She prepares her drink when she arrives at her set time (looking at her watch), as if using alcohol like a prescription medicine. The playing of cards, getting dinner, trying to make it tastier, spitting it out and trashing it, then having her timed drink, then eventually looking into a crystal ball might have been shortened.

But this is Martha’s imagined view of what her mother does alone. It doesn’t work as fluidly as the other scenes do. Perhaps this is because none of Martha’s interior dialogue is externalized.We only see her outer actions in silence. Martha doesn’t imagine Phyllis’ interior dialogue because that might require an empathy for her mother which she doesn’t have. It is an interesting disjointed scene, perhaps for a very good reason that exposes Martha’s shortcomings about her mother, particularly in understanding and empathizing with her.

However, Keenan-Bolger and Lange bring the play home with the poignant, affirming ending. For the first time, as Martha speaks to an ethereal Carl sitting in a chair reading in a dimly lit section of the stage, she gives herself a break from internalizing her anger. She allows herself to see what was perhaps there all along in her mother’s opinion of her. She does this after she casts all the anger from the past aside. What penetrates is Martha’s new realization of a Phyllis she never understood before. It is a long awaited for moment of feeling that opens a flood of love between them. Vogel leaves the final scene open for audience interpretation as it should be. Either way, the misshapen puzzle pieces fit into redemption and forgiveness.

Mother Play, a Play in Five Evictions is a must-see. It runs with no intermission for one hour and forty-five minutes. The Hayes Theater is on 210 West 44th Street between Broadway and 8th Avenue. https://2st.com/shows/mother-play

Mary Louise Parker, David Morse Renegotiate Their Roles in the always amazing ‘How I Learned to Drive’

Paula Vogel’s Pulitizer Prize winning How I Learned to Drive in revival at the Samuel Friedman Theater is a stunning reminder of how far we’ve come as a society and how much we’ve remained in the status quo when it comes to our social, psychological, sexual and emotional health, regarding straight male-female relationships. Pedophilia and incest by proxy are as common as history and not surprising in and of themselves. On the other hand how particular male and female victims lure each other into illicit sexual self-devastation is unique and horrifically fascinating.

This is especially so as leads Mary-Louise Parker, David Morse, and director Mark Brokaw put their incredible imprint on Vogel’s trenchant and timeless play. Interestingly, Parker and Morse are reprising their roles from the original off-Broadway production, with original director Mark Brokaw shepherding the Manhattan Theatre Club presentation. Parker (Li’l Bit) and Morse (Uncle Peck) are mesmerizing as they portray characters who manipulate, circle and symbolically search each other out for affection, love and connection. The relationship the actors beautifully, authentically establish between the characters is heartbreaking and doomed because it cannot come out from under the umbrella of the culture’s changing social mores, Peck’s psychological illness from the war, and Li’l Bit’s familial, sexual psychoses.

How I Learned to Drive reveals what happens to two individuals (a teen girl and an adult male), who engage in the dance of psycho-sexual destruction while negotiating feelings of desire, love, attraction, fear and guilt under society’s and family’s repressive sexual folkways and double standards. What makes the play so intriguing is not only Vogel’s dynamic and empathetic characterizations, it is her unspooling of the story of the key sexual-emotional relationship between Li’l Bit and Peck.

Li’l Bit and Peck’s relationship is not easily defined or described as sexually abusive, though in a court of law, that is what it is, if an excellent prosecutor makes that case in a blue state. However, in a red state, it might be viewed differently. Consider 13 states in the US allow marriage under 18, and Tennessee has recent records of marriages of girls at 10 years-old with parental or judicial agreement.

Sexual abuse, if the players are amenable and influencing each other for reasons they themselves don’t understand, is a slippery slope depending upon the state’s political and social folkways, the familial mores and the perspectives of the players themselves. Ironically and eventually, a turning point comes IF the abuse is recognized and the relationship ends whether exposed to the light of public scrutiny or not as in the case of Lil’Bit and Peck.

In Vogel’s play, how and why Lil’Bit ends her forbidden relationship with Uncle Peck is astounding, if one looks to Vogel’s profound clues of Lil’Bit’s emotions which are an admixture of confusion, regret, love, affection, annoyance, fear and disgust of going legal/public and against family, for example, her Aunt, whom she has “stolen” Peck from. Indeed, Lil’Bit is willing to forget what happened and stop their secret “drives” after she goes away to college. But when she is disturbed by Peck’s obsessive letters, and drinking to excess, she flunks out. She is haunted by the events (sexual grooming in 2022 parlance), that began when she was eleven, so she ends “them.” The last time she sees him is in a hotel room, though at 18-years-old she is of age and old enough for intercourse under the law. However, she must be willing.

Her ambivalence is reflected when she lies down with him on a bed, obviously feels something but gets up. Yes, she agrees to do that after she has two glasses of champagne. But when he asks her to marry him and go public with their affection with each other, it’s over. The irony is magnificent. When they were secret, she let it happen and told no one and continued her drives with him until college. The public exposure of a public marriage is loathsome for her as she would have to confront what has transpired between them for seven years.

As Vogel relates the process through Lil’Bit’s sometimes chaotic flashback/flashforward, unchronological remembrances, we understand the anatomy of Peck’s behavior and hers. The finality of this revelation occurs when she divulges the precipitating abusive event on Lil’Bit’s first driving lesson in Peck’s car. Driving becomes the sardonic, humorous metaphor by which Peck reels her in, linking her desires to his (part of the affectionate aspect of grooming). Her mother (the funny and wonderful Johanna Day), despite negative premonitions, allows her eleven-year-old to go with her uncle, though she “doesn’t like the way” he “looks” at her.

The dialogue is brilliant. Li’l Bit chides her mother for thinking all men are “evil,” for losing her husband and having no father to look out for her, something Uncle Peck can do, she claims. Li’l Bit uses guilt to manipulate her mother to let her go with him. Her mother states, “I will feel terrible if something happens” but is soothed by Li’l Bit who says she can “handle Uncle Peck.” The mother, instead of being firm, says, “…if anything happens, I hold you responsible.”

Thus, Li’l Bit is in the driver’s seat from then on, responsible for what happens in her relationship with Peck, given that warning by her mother. This, in itself is incredible but the family has contributed to this result in their own personal relationships with each other as Vogel reveals through flashbacks of scenes which have psycho-sexual components between Peck and Lil’Bit and Lil’Bit and family members. However, this is a play of Lil’Bit’s remembrance. We accept her as a reliable narrator, knowing that things may have been far different than what she tells us. As she is coming to grips with what happened to her as a child, we must admit, it could have been worse, or better, any of the representations less or more severe. Indeed, she is narrating this story of her teen years as a 35 or 40-year-old who is plagued by the tragedies of the past which include what happens to her Uncle which she may feel responsible for.

During the flashbacks which are prompted by themes of unhealthy sexual experiences (including male schoolmates’ obsession with her large breasts), Lil’Bit reveals prurient details about her family’s approach toward their own sexuality and hers. It is not only skewed, it is psychologically damaged. For example, Lil’Bit explains they are nicknamed crudely and humorously for their genitalia. Her grandfather represented by Male Greek Chorus (the superb Chris Myers), continually references her large breasts salaciously, one time to the point where she is so embarrassed she threatens to leave home. Of course, she is comforted by Uncle Peck who understands her and never insults or mocks her. However, in retrospect, he does this because it’s a part of their “close” driving relationship.

In another example her mother chides her grandmother for not telling her about the facts of life because she was most probably gently forced into sex, got pregnant, had a shotgun wedding and ended up in an unhappy, unsuitable marriage. From the women’s kitchen table of women-only sexual discussions, we learn that grandmother married very young and grandfather had to have sex for lunch and after dinner, almost daily. And with all that sex, grandma never had an orgasm.

When Lil’Bit asks does “it” hurt (note the reference isn’t to love or intimacy or even the more clinical intercourse), the grandmother portrayed by the Teenage Greek Chorus (Alyssa May Gold who looks to be around a teenager), humorously tells her, “It hurts. You bleed like a stuck pig,” and “You think you’re going to die, especially if you do ‘it’ before marriage.” The superb Alyssa May Gold is so humorously adamant, she frightens Lil’Bit so that even her mother’s comments about not being hurt if a man loves you are diminished. Indeed, reflecting on her mother’s unwanted pregnancy and her grandparents’ cruelty forcing her mother to marry a “good-for-nothing-man,” the discussions are so painful Li’l Bit can’t bear to remember their comments “after all these years.”

Thus, romance, love and affection and sweet intimacy are absent from most discussions about men who are neither sensitive, caring, loving or accommodating to her mother (an alcoholic with tips on drinks and how to avoid being raped on dates), and grandmother who never had an orgasm with her beast-like husband. Only her Aunt seems satisfied with Uncle Peck, who is a good, sensitive man, who is troubled and needs her, and who reveals that she sees through Li’l Bit’s slick manipulation of him. She knows when Li’l Bit leaves for college, her husband will return to her and things will be as before. An irony.

Vogel takes liberties in the arc of the flashbacks with intruding speeches by family. As all memories emerge surprisingly when they are disturbing ones, Li’l Bit’s are jumbled. The exception is of those memories which organically spring from the times Peck and Li’l Bit drive in his car as he teaches her various important points and helps her get her driver’s license on her first try. After, they celebrate and he takes her to a lovely restaurant and she gets drunk.

Again and again, Vogel reveals Peck doesn’t want to take advantage of her because he will not do anything she doesn’t want him to do, he proclaims. Thus, his attentions are normalized. And Lil’Bit shows affection yet, at times apprehension, ambivalence and acceptance. On their drives, Peck has become her quasi father figure, a confidant and supportive friend. Thus, she accepts his physical liberties with her (unstrapping her bra, etc).

Because the scenes are in a disordered cacophony, each must be threaded back to the initial event of Peck’s molestation which happens at the end of the play. SPOILER ALERT. STOP READING IF YOU DON’T WANT TO KNOW WHAT HAPPENS.

The mystery is revealed why Li’l Bit continues her driving lessons until she goes to college, and even then ambivalently meets him in the hotel room where he proposes. When she is eleven (Gold stands off to the side reminding us of her age as Parker and Morse enact what happens), she touches Peck’s face as she sits on his lap. While driving, Peck touches Li’l Bit who cannot reach the breaks, but only holds her hands on the wheel so she doesn’t kill them both. Though she accepts what he does initially, then tells him to stop, he ignores her. Then she states, “This isn’t happening,” making the incident vanish, though it happens. And she tells us, “That was the last day I lived in my body.”

It is a shocking moment and is a revelation at the play’s near conclusion. Prior to that Morse is so exceptional we take Peck at his word, that he won’t do what she doesn’t want him to. In the last scene, we see he lies. Likewise, we realize the impact of his horrific behavior on Li’l Bit. When she is twenty-seven as an almost aside, in the middle of the play, she cavalierly tells us she had sex with an underaged high school student, then reflects upon her experiences with Peck. She realizes for Peck, as for herself, it is the allure of power, of being the mentor and teacher to someone younger, using sex to hook them like a fish.

By this point, we have learned that Uncle Peck became alcoholic, lost everything and died of a fall seven years after she never saw him again. At this juncture in her life, perhaps she is reconciling and working through all of those traumatic experiences growing up. And then Lil’Bit tells us of her love of driving as she gets into a car and Peck’s spirit gets into the back seat and races down the road with her as the others stand outside and watch. Indeed, taking Peck with her, the damage is everpresent. Though she will never die in a car, she has learned to destroy others with the driving techniques of allurement, denial and “gentle affection” Peck showed her.

The actors do admirable justice toward rendering Vogel’s work to be magnificent, complex and memorable. With her profound examination via Li’l Bit’s remembrances, we see Parker’s and Morse’s astonishing balancing act inhabiting these characters and making them completely believable and identifiable. The audience tension is palpable with expectation as we become the voyeurs of a slow seduction: we wonder if the cat who mesmerizes the bird will really pounce or the bird merely enthralls the cat, knowing its wings enables it to an even quicker escape, leaving the cat in devastation of its own faculties.

Rachel Hauck’s minimalist set is suggestive of memory without a conundrum of details, just the bare essentials to fill in the locations with the time stated by the chorus (Johanna Day, Alyssa May Gold, Chris Myers). The depth and sage layering of Vogel’s production envisioned by Brokaw disintegrates the superficiality and sensationalism of pundits on the left in #metoo and on the right with #QAnon pedophile conspirators. It echos the tragedy of the human condition and the revisiting of the sins upon each generation who dares to breathe life into the next set of progeny.

Kudos to the creative team Dede Ayite (costume design), Mark McCullough (lighting design), David van Tieghem (original music and sound design), Lucy MacKinnon (video design), Stephen Oremus (music direction & vocal arrangements). This is another must-see with this cast and director who have lived the play since before COVID. You will not see their likes again. For tickets and times go to https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2021-22-season/how-i-learned-to-drive/

‘Paula Vogel in Conversation With Linda Winer’

(L to R): Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paula Vogel, Linda Winer in NYPL for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, League of Professional Theatre Women collaboration, ‘Paula Vogel in Conversation With Linda Winer at Bruno Walter Auditorium (photo Carole Di Tosti

The League of Professional Theatre Women’s Pat Addiss and Sophia Romma again have successfully collaborated with Betty Corwin, who produces the New York Public Library’s Oral History Interviews, to present an enlightening, joyous evening with one of Broadway’s hottest playwrights, Paula Vogel. In conversation with Linda Winer, long-standing theater critic of Newsday, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright discussed her life, her work and the journey of her play Indecent from conceptualization through development, regional theater production and Off Broadway right up to its current run at Broadway’s Cort Theatre. The immutably themed Indecent has been nominated for a Tony Award in the category of Best Play. It is not only a must-see, it is a must-see two or three times over for its metaphors, themes and sheer genius.

Paula Vogel, a renowned professor of playwriting (Brown-two decades, currently Eugene O’Neill Professor of Playwriting (adjunct) at Yale School of Drama, Playwright-in-residence at Yale Rep) generously shares her time and dynamism with global communities. She conducts playwriting “boot camps,” and playwriting intensives with various organizations, theater companies and writers around the world. What is smashing is that Vogel not only is a charming, vibrant raconteur, she is an ebullient, electricity-filled advocate of the artist within all of us.

Pullitzer Prize-winning playwright Paula Vogel, a presentation by The NYPL for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center and League of Professional Theatre Women, ‘Paula Vogel in Conversation With Linda Winer, Bruno Walter Auditorium (photo Carole Di Tosti)

In her philosophy and approach toward theater, we are all story tellers, we are all playwright,s and we must cultivate the citizen artist within to insure that the theater arts are accessible and relevant to all cultures and populations, not just the “haves.” What she discussed about the current state of theater arts past and present was profound and prescient in response to why it took her so long to get to Broadway. Vogel reminded the audience that in the 1980s there were about 50 innovative, theme-rich plays on Broadway exemplified by The Elephant Man and M Butterfly. Such plays dealt with difficult issues that brought audiences together in a profound communal experience. Currently in 2017 there are a handful of productions that effect this. Commercialism has enveloped Broadway.

Hence, Vogel expressed a motivating joy that perhaps we should all entertain. We should roll up our sleeves to fight the good fight against philistine commercialism and consumerism and Byzantine gender and racial bias. Such dampening restrictions and discriminations parade behind the notion that film and theater are essentially liberal mediums. Vogel introduced the thought that they are the opposite. To her way of thinking there is a profligate conservatism akin to that of corporate America that hampers theater innovation and prevents provocative theater production to readily make it to Broadway.

However, she did affirm that the next generation of playwrights, whether older or younger, are seeing an explosion of work featured Off Broadway and Off Off Broadway which is where a lot of the innovation and experimentation has found a home. That aspect of the theater is thriving and in the upcoming years we can expect an elegance of defining work that will have an illuminating impact on Broadway.

A believer of reverse capitalism, that supply increases demand, Vogel’s ideas and effervescence are contagious. She “spreads the word” and brings the community of theater wherever she visits, from Austin, Texas to Sewanee, Shanghai Theatre Academy in China, from Minneapolis to the neighborhood near the Vineyard Theatre in New York City. And together she and her audience of all ages across the communities (from 15-90), of seasoned writers and playwrights and neophytes alike, experiment, grow and enjoy writing and reading plays during her intensives.

Her current playwriting boot camps (they used to take a week to do) to make live theater a communal experiment much like its original creative form as a social, cathartic experience resonate today. They make complete sense especially at a time when artistic shallowness manifested in some entertainment forms has achieved a noxious superfluidity that really needs to die a death (my thoughts).

(L to R): Paula Vogel, Linda Winer, ‘Paula Vogel in Conversation With Linda Winer, in a collaboration by The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center and the League of Professional Theatre Women (photo Carole Di Tosti)

Some of the highlights of Paula Vogel’s discussion with Linda Winer, who was a wonderful interviewer, revolved around how she conducts her “bootcamps,” culminating in bakeoffs to spur on a fountain of creativity. In response to how her Pulitzer Prize-winning play Learning How to Drive was produced Off Broadway but never made the transfer to Broadway, she repeated an incisive comment from the past, “How often do the girls get to play with the big expensive toys?”

Now that Vogel’s Indecent and colleague Lynn Nottage’s play Sweat also transferred to Broadway from the Public Theater, Vogel laughingly acknowledged that for both of them, the expensive toys are “a lot of fun.” Vogel stated that when one acclimates to the house size, whether the play is in a 60 seat theater or a 200 seat theater, the effort and the intensity of the work process is the same. Vogel joked, “The only difference is I’m not sleeping on a sofa bed.” Indeed, with Indecent, Vogel has graduated to a mattress and a bed, “more expensive toys.”

Vogel discussed the evolution of Indecent which was fascinating. In her twenties she had read The God of Vengeance, by Sholem Asch, the play upon which Indecent revolves. She was mesmerized by the transcendent love scene between the pious Jewish father’s daughter and one of the prostitutes who works for him in the brothel below their apartment. When the world renowned Yiddish play was translated into English and brought to Broadway in 1923, the cast, director and producer were arrested for obscenity, even though some of the love scenes were cut. The play received a greater following and lasted 133 performances, but there was a trial after the play closed. The Court of Appeals overturned the convictions of the director and producer in 1925.

Twenty years after Vogel read Asch’s play, she learned that Rebecca Taichman was attempting to direct the obscenity trial for her thesis. Vogel learned of her work and pronounced her a genius. Vogel was inspired when she received a call from Taichman to collaborate on a play about the events surrounding the trial of Asch’s play. During their conversation Vogel had a lightening-like vision seeing a scene from the play which she stated “always happens” (it happened with Learning How to Drive) when she knows she can write a particular play. Having read up on Yiddish Theater, she told Taichman, “I think this is a play way beyond an obscenity trial.” Taichman was thrilled at her enthusiasm. Vogel admitted that this was around nine years and 40 drafts ago.

(L to R): Pat Addiss, Paula Vogel, ‘Paula Vogel in Conversation With Linda Winer presented by NYPL for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center and League of Professional Theatre Women (photo Carole Di Tosti)

They workshopped at Sundance Theatre Lab (2013) and after many drafts and other workshops they put it on at Yale Repertory for the first time with the music, choreography and staging. Vogel joked the “flop sweat” was prodigious. Taichman’s and Vogel’s shirts were sticking to their backs. Since then it has moved on and was performed at La Jolla Playhouse in Fall 2015 and in May 2016 was produced at the Vineyard Theatre in New York City.

There is such enthusiasm for the production since Yale (2015) that the ensemble, the musicians, the stage manager and the assistants have remained together. As Vogel says, “We’ve all moved together as one.” This never happens with a production that transfers to Broadway. If it does, it is extremely rare. Vogel laughingly joked they have become a family. When two children were born during the evolution of Indecent, Vogel commented she has become like a godmother to both.

What a memorable evening! Vogel is about fun, about community about connections, about living and creating whatever comes next. That spontaneity and flexibility is like jumping off into the darkness, knowing you will land on soft ground at sunrise. The moment you think about the jump, you stop yourself. Vogel is not about stopping. She’s there already and beckoning us to join her. Why not?