Blog Archives

‘Baldwin & Buckley at Cambridge’ at the Public, Review

Baldwin & Buckley at Cambridge, the 1965 debate of James Baldwin and William F. Buckley, Jr. at the Cambridge Union, University of Cambridge, UK is receiving its New York Premiere at The Public Theater. You need to see this production presented by Elevator Repair Service (Gatz, The Sound and the Fury) for many reasons. First, it’s vitally important for us in this present moment to hear and understand Baldwin’s criticism about our nation from the perspective of an articulate novelist, playwright, essayist, poet, identified as one of the greatest Black writers of the Twentieth Century. The production, which captures the debate in its entirety, will also help you understand Baldwin’s realistic acknowledgement of American attitudes and sensibilities, many of these carryovers to our present society and divisive culture, whether we are loathe to admit it or not.

The unadorned, bare bones production highlights the arguments Baldwin and Buckley presented at Cambridge in response to the question, “Has the American Dream been achieved at the expense of the American Negro?” With a minimalist set, two desks, chairs, lamps staged with the audience on three sides at the Anspacher Theater, the evening replicates the words if not the tone, ethos or dynamic drama of Baldwin (Greig Sargeant) and Buckley (Ben Jalosa Williams) in their face-off.

It is a worthy triumph of ERS to re-imagine these two titans, one eloquently speaking for Black America, the other a conservative writer and National Review founder. The latter supported a slow walk of desegregation which Blacks must “be ready for,” and were “not yet ready for.” Baldwin’s and Buckley’s perspectives reflected national attitudes, especially after the legislative gains made for Blacks in 1954, 1964 and 1965 which Baldwin didn’t trust because the power structures of the South and North didn’t adequately enforce the laws. In viewing their comments now, as our nation experiences “in-your-face” racism and discrimination, that would overthrow all gains (revealed in striking down Roe vs. Wade and most of the 1965 Voting Rights Act) the concepts in the debate between Baldwin and Buckley are highly relevant and worthy of review.

The inherent drama of the debate, its electric personages, and the crisis of the time eludes the actors and the director. Indeed, perhaps the task is impossible without sufficient artistry, and imagination to suggest what once was, the frenetic and feverish times of the country that in 1965 saw the Watts riots, which Baldwin alludes to at the end of his speech.

When Baldwin and Buckley debated, America was still fighting segregation in the deep South, the effects of which Cambridge student Mr. Heycock (Gavin Price on Saturdays) discusses to introduce Baldwin’s arguments. He mentions statistics quoted by Martin Luther King, Jr. when they conducted a protest supporting voting rights in Alabama. Heycock states, there were more Negroes in jail for protesting than on the voting rolls. He enumerates other statistics. These identified the extent to which Blacks had been excluded from the White society’s opportunities and their aspirations to achieve the American Dream: jobs with benefits, college educations, economic prosperity, home ownership and more.

As both Heycock and later Sargeant’s Baldwin make clear during their fact-laden presentations, in no way was the Black experience in America “separate but equal” to that of Whites. Their lives, their worlds, their perspectives, opportunities and approach to daily living was anything but equivalent.

Though this was especially so in the South, the quality of life disparities also were prevalent in Northern cities like New York, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles. There, Blacks were shoveled into the projects branded as a Utopian “urban renewal.” Actually, there was no renewal, as Blacks were crowded into broken-down buildings and crime-ridden ghettos, where rats flourished and the garbage spilled over into the streets. All of these points, Sargeant’s Baldwin mentions, disputing that Blacks have an equal opportunity in achieving the “American Dream,” which is obtain by Whites at Black’s expense.

The debate is a historic call to remembrance and worthy as such, which is why it bears being watched on YouTube, after seeing the Public’s production, directed by John Collins. The YouTube video reveals the unmistakable ambience of Cambridge and the scholars and students present in their formality and sobriety, laughing at Baldwin’s wit and wisdom and sometimes laughing with ridicule at Buckley’s pompousness and stumbles into bigotry.

Indeed, what is absent from the Public Theater production is this sense of moment. Missing is the ambience of setting and the nature of the audience which played a role in relaying the importance of the Baldwin and Buckley debate. These two giants in their own right honored Cambridge with their presence and concern, conveying American voices and perspectives. The gravitas is lacking in the production and is a possible misstep. Though an announcement is made as to the setting, more should have been done to convey the place and time. With a minimum of dramatization, the production wasn’t as dynamic as it could have been.

Creatively conveying time and place was not the choice of ERS or director Collins. Thus, Baldwin & Budkley at Cambridge is uneven. In structure and format the production follows the original debate. The elements are modernized, costumes in modern dress, not the black bow tie and suit worn for the formal Cambridge debate.

Also, somewhat confusing is that Price’s Heycock acknowledges the Lanape Indigenous Tribe who owned the land the Public Theater rests on. Then immediately he segues into the original debate structure. Perhaps as is done with other productions at the Public, a voice over by Oskar Eustis honoring the Lanape would have been less confusing. The separation of the present America from the debate setting is needed so the audience might reflect on the history of the land. After a pause, the setting of Cambridge, 1965 could then be established.

When Heycock finishes his introduction, Cambridge student Mr. Burford (Christopher-Rashee Stevenson) introduces Buckley’s argument, that it is not true that “the American Dream has been achieved at the expense of the American Negro.” To refute this Mr. Burford points out that 35 Black millionaires have achieved the American Dream. This justification that Blacks have attained the dream and not at the expense of Blacks is an example of the convoluted logic that will follow in Buckley’s confused and misdirected arguments.

Burford’s belittling statement in ignoring the huge unequal and disproportionate number of the few wealthy Blacks to numerous wealthy Whites deserves laughter and ridicule. Interestingly, the audience at the Public didn’t respond, as bigoted as the comment was. Possibly the lack of context of time and place contributed to an absence of audience engagement with Burford’s obnoxious statement and at other times during the performance.

Identifying the number of Black millionaires, while ignoring the large percentage of Blacks who live in poverty, evidences the superficiality of Buckley’s arguments which follow Burford’s introduction. As Williams’ Buckley launches into his presentation, we understand that the reality that Baldwin just portrayed about the Black experience in America, will in no way enter in to Buckley’s discussion. Indeed, he dismisses and ignores Baldwin’s brilliant conceptualizations, something which Baldwin intuits that the White culture does to perpetuate the status quo. Throughout his presentation Buckley doesn’t acknowledge that White culture controls, creates and dictates the Black experience. In no way is Baldwin’s picture of reality confronted by Buckley in his disjointed and at times abstruse speech.

Buckley diverges from Baldwin’s statements so that he does not dispute that the American Dream exists at the expense of Black exploitation. He ignores Baldwin’s dense discussion that the American Dream by its very nature in the White culture’s understanding nullifies its existence if Blacks are to be a part of it. For the American Dream to exist, Baldwin suggests from the White perspective, Blacks must be excluded and given little opportunity to achieve it. Blacks can’t be a part because it necessitates exploitation of themselves. Baldwin’s point is that the dream only exists for Whites. Blacks are a part only in so far that they are at the bottom of the power structure, the foundation upon which Whites step up and rise, taking with them all the spoils, all the opportunities.

Sargeant’s Baldwin is wry and not as nuanced, expressive and dramatic as he might have been. On the other hand, Williams’ Buckley is vital, stirring and engaging. Clearly, in the Public Theater production, Buckley won. I found myself dropping out as Sargeant’s portrayal missed important beats. Williams’ sharp edginess and movements kept my interest. Conversely, Price’s Heycock was portrayed with vitality. Stevenson’s Burford was adequate.

Interestingly, after the debate Sargeant’s Baldwin sits with friend and playwright Lorraine Hansberry (Daphne Gaines). Their interchange reveals their close friendship. Unfortunately, the scene is too brief and should have delved deeper. At the very end, Sargeant takes off the mantle of Baldwin in his most authentic moment. He acknowledges the company’s own politically incorrect historic racism when ERS cast White actors to play Black roles in their early versions of The Sound and the Fury. To identify a past that we are still trying to become free of, even the most well meaning of us, seems counterproductive, guilty and fearful. I look forward to a time when theater moves beyond this stance which in itself is disingenuous and “protests too much.”

Clearly, at this time it is appropriate that the debate of Baldwin & Budkley at Cambridge be re-imagined. We are at a crossroads. This is not 1965. We are not in Cambridge, however, the ideas from our racist past that were entrenched, have been redeemed as useful and justifiable for us in the present. At no other time in history having attained what we thought was racial progress, have we been so duped by the residual racism that existed culturally into believing it was harmless. Its dangers have always been there and liberals have been blind to it despite warnings by Black and Brown critics.

Baldwin knew, he saw. The Black reality and White world were as clear as day. He understood that the White reality was convinced of its craven rightness to oppress and suppress Blacks to achieve White agendas at Black expense. Today, this horrific White reality is most visible in law enforcement abuse of Blacks, in the broken justice system that incarcerates Blacks disproportionately, in the exclusion of Blacks in corporate empires, in every institution that harbors systemic racism.

And the economic oppression is growing worse to include everyone except the .001%. These truths existed sub rosa for decades as the gap between the wealthy and everyone else widened. However, it took an egregious and criminally-minded opportunist in former president Donald Trump to justify and promote a resurgence of open hatreds branding the necessity of racist oppression, and authoritarianism ruling the underclasses, using media PR of lies and obfuscation.

For that final reason, Baldwin & Budkley at Cambridge is an extremely vital production which must be seen. For tickets go to their website: https://publictheater.org/

‘Coal Country’ is Amazing

When money and wealth become more important than the lives of others, that is the time to write a play with powerful, sonorous music. Oh, not to uplift the CEOs who collect the millions like Don Blankenship of Massey owned Performance Coal Company. No. The play should uplift and memorialize the ones who die because of that CEO’s greed, selfishness and refusal to accept accountability for what many have called murder. Above all the play must repudiate the wealthCy’s Puritan assertions that money and power make right. They don’t. Not now, not ever.

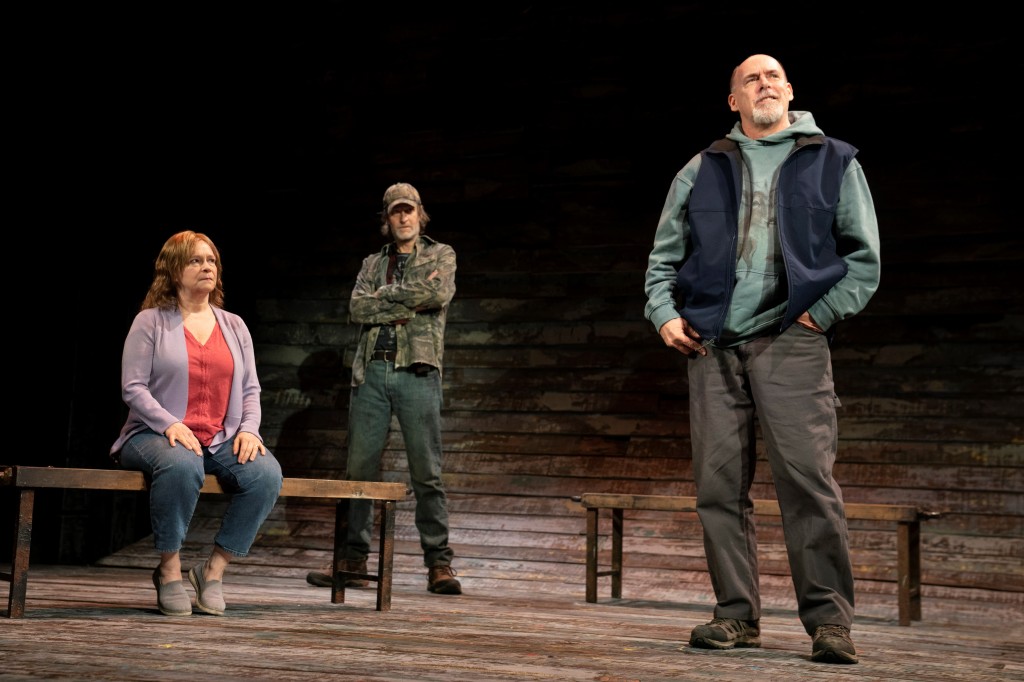

Coal Country is a docu-drama with incredibly relevant themes for us today. The riveting, masterful work written by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen with original music by Steve Earle in a fabulous encore presentation by Audible and the Public Theater seems more impactful each time it is presented. We can never get enough of this exceptionally performed, shining work which runs at the Cherry Lane Theatre until 17 of April.

Though the worst of human nature asserts its primacy, poignant, moving stories like those in Coal Country are timeless in revealing that love despite tragedy culturally work us toward enlightenment. The voices of those who have been wrongfully snuffed out can resonate with meaning. This is especially so when fine artists like Blank, Jensen, Earle and superb performers effect those voices to channel the great moral imperative. What is good, what is true, what is valuable is never lost. It lives on.

The themes which the playwrights and songwriter ring out in Coal Country focus on the devastating catastrophe known as the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster of 2010, which cost 29 West Virginians their lives. Through family eye-witness accounts cobbled together in a tapestry of poetic beauty, vitality and grace, we learn the facts about the huge machine that operated over- capacity 24/7 on the long wall, sheering off the finest, most valuable coal so Blakenship could get his contract percentage of the mine’s earnings of $650,000 a day.

We learn through the accounts of union miners like Tommy (Michael Laurence), Gary (Thomas Kopache), and “Goose” (Joe Jung), how and why government inspectors never found the broken systems that allowed low oxygen levels to increase the build-up of methane gases and thick coal dust that caused the massive explosion. As the experienced miners relate how the broken sprinklers ineffectively doused the sparks created in machine operations that ignited the coal dust and methane behind the long wall, the final picture of egregious negligence and rapacious lust for money clarifies in the blood of innocents merged with the blood of family bonds.

Tommy, Laurence and Gary discuss how the power of the union to protect and respect the miners’ rights in the past has been subverted by the CEO and company, and government de-regulation. The owners who bought the mine hired a large percentage of non-union men, who didn’t dare “speak up,” to government inspectors and the FBI about extremely unsafe conditions in the mine. They feared reprisals. The question of payoffs arises and dead ends. We learn how those miners who did “say something” were warned and ignored. Miners were rendered voiceless against the inevitability of their deaths, because Blankenship was on a mission. No one was going to stop him.

As families identify bodies on blankets on the gravel, some collapse. Roosevelt (Ezra Knight) who identifies his father, who appears to be “asleep,” remains calm until his mother comes. They weep together. As others express outrage, the families of four missing men wait to hear whether or not their loved ones cheated death. Finally, the wait is over. None make it out. Tommy, who loses his son, his nephew and his father, waits to spill the news, overcome with pain.

Judy (Deidre Madigan), a doctor who lost her brother in the catastrophe rides a roller coaster of emotional expectation. First, she believes her brother died. Then she believes he found refuge. Then, all is finality. She describes that she feels she is an outsider because of her socioeconomic status. But emotion and love transcend economics; she is one of them. Her brother is dead and though the medical examiner tells her not to, she insists on seeing his remains. It is ironic that even her medical background does not prepare her for what the mine did to him. It is beyond calculation. In pieces, her brother is without human form.

One by one seven family members tell their story of a simple, satisfying life before the catastrophe in a community that mined for generations. Indeed, the mountain supported and nurtured them until it was bought over by Massey Energy and a new CEO came to town. We learn of the loving relationships between Mindi (Amelia Campbell) and Goose, and Patti (Mary Bacon) and Big Greg who dies leaving Little Greg traumatized by the loss of his dad and Patti when he is taken away from her. And interspersed with their stories, Steve Earle’s country ballads lyrical and poignant drive home the resonance of their love and remembrances of their dear ones. They live in his songs and echo in the actors’ mesmerizing performances.

Blank and Jensen (the husband-wife team who created The Exonerated), choose to present this dynamic piece as a flashback after Earle (playing guitar), opens with two songs that set the themes: “John Henry,” and Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” Cleverly, the action begins in the courtroom at the end of Don Blakenship’s trial as Judge Berger (Kym Gomes), states they cannot read their “Victim Impact Statements.” What family could never speak in court, they relate to the court of public opinion (the audience who sees this play).

The flashback comes full circle back to the court, so the audience hears Blankenship only gets one year in jail and a fine of $250,000. Arrogantly, Blankenship uses that money to run Ads and create pamphlets in which he characterizes himself as the victim of government as a “political prisoner.” Nevertheless, in final, moving encomiums, each family member details how they remember their loved ones who live on in their hearts and in this production which has called. out to music the names of all who died in the UBB mine explosion.

With minimalist but trenchant symbolic Scenic Design (Richard Hoover), effective Lighting Design (David Lander), Sound Design (Darron L West) and Costume Design (Jessica Jahn), Coal Country is an amazing revival. It is profound and memorable in scope and power. Don’t miss it this time around. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.cherrylanetheatre.org/coal-country

‘Mojada’ by Luis Alfaro at The Public, A Superb Update of ‘Medea’ via the Migrant Crisis

(L to R): Benjamin Luis McCracken, Socorro Santiago, Sabina Zúñiga Varela in ‘Mojada,’written by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

Luis Alfaro’s riveting update of the Greek Tragedy Medea spun out against our current immigrant crisis is authentic, primal and timely with exceptional direction and evocation by Chay Yew. I saw it this weekend, one day prior to the Trump announced ICE raids designed to terrorize and apprehend illegal immigrants, “wetbacks” (mojados) with the intention of incarcerating them until eventual deportation. The “raids” failed miserably in their execution, but not their intent to terrorize.

Alfaro adroitly reinterprets the migrant crisis and parallels it with the story of Medea, the sorceress who dispatches her children after her husband Jason dumps her and marries the king’s daughter. However, he makes significant changes in the characterizations, softening and humanizing Medea and Jason and removing the notions of vengeance and anger by changing it to despair, isolation, loneliness and desperation for the character of Medea. Additionally, unlike the classic Medea, Alfaro never leaves off Jason’s love and tender concern for Medea, shifting her enemy conflict away from Jason to her rival Pilar.

Alex Hernandez, Sabina Zúñiga Varela in ‘Mojada,’ by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

Alfaro’s Medea is the the indigenous Mexican “mojada” portrayed by the always present and heartfelt Sabina Zúñiga Varela. Varela gives an exceptional, thrilling portrayal of the emotionally driven and abused spiritualist who has been raped on their journey to the United States and still psychologically suffers from the trauma. Her servant/family member tells us early on in the play that despite the herbs she gives her, she cannot heal. Later, as Medea revisits her horrific journey to “freedom” in America in a flashback sequence, we discover why she cannot “heal;” the trauma has frozen her soul and filled her with fear and death.

Medea’s partner Jason (the excellent, charming Alex Hernandez) is one she adores. Despite the sacrifice of her wholeness and happiness, she stays with him and they finish their journey North with their son Acan (the lively, adorable Benjamin Luis McCracken) and their servant Tita (the humorous, wonderful Socorro Santiago) so Jason may fulfill his ambitions. In a later reveal, we discover why Medea had to leave. When Jason suggests they start over in America, she has little choice but to join him and remain under his protection. However, Medea is confused and unable to self analyze and straighten out her severe emotional problems after their arrival.

(L to R): Alex Hernandez, Sabina Zúñiga Varela, Socorro Santiago in ‘Mojada,’ written by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

Early on in the production we discover that Jason wants “the American Dream.” Clinging to Jason and her family as her only hope, Medea believes in Jason’s love and good will. She indulges his promises of a better life for her and their son in the alien American culture. As the play begins, all appears calm for they have settled in Jackson Heights, New York and both have jobs and earn money while Tita cares for Acan. Jason works construction and Medea works at home, all of which is a divergence from the classic play Medea which begins after Jason and Medea end their marriage.

Alfaro seeks to represent his Mexican Medea with a strong faith in herbal medicine that Tita concocts as well as a ritual morning obeisance to the four winds which she practices with Acan as an incantation, a recitation to recall their past life and infuse it with them in the present so they never forget what they have given up. As an indigenous Mexican, Medea is close to the spiritual plane. Her incantation’s powerful symbolism to her mind strengthens the connection with their homeland to which Medea daily seeks a return, despite Jason’s successful forward direction in becoming prosperous and in encouraging a better life so they may become American citizens. Though Alfaro’s Medea lacks the status of a princess, his portrayal of her beauty, innocence and purity (she is in white throughout the play) represents an everywoman. His depiction symbolizes the core ethos of what makes women noble and sanctified. Varela embodies these traits and heightens the honor of Alfaro’s vision for this character which makes her desperate, hopeless fall from grace all the more tragic and poignant.

(L to R): Sabina Zúñiga Varela, Vanessa Aspillaga in ‘Mojada,’ by Lluis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

Medea, a professional level seamstress, works diligently at supplementing their family income by creating a veritable sweatshop in their home where she makes gorgeous clothing at a pittance while her “bosses” reap a substantial profit for each item and exploit her labor because of her non-status as an illegal immigrant without a green card or work visa. The theme of workers being exploited for their cheap labor while greedy individuals who prey upon their circumstances reminds us of the timeless status quo of the workers vs. their corporate overseers and highlights the plight of undocumented workers. It also is reminiscent of the greed of corporate America which refuses to pay the proper value for their workforce that makes them profitable while paying their CEOs who largely schmooze and network lazily 300 times the amount.

In Medea’s life as an undocumented worker is the everpresent fear that she, her son and Tita may be turned in and deported. This haunts Medea and contributes to her agoraphobia so that she prefers to stay at home in Queens away from the chaos of New York City life that is unfamiliar to her. Her status oppresses her for she has no way to bargain with her employers who “call the shots” and pay her the minimum locking her into an indentured servitude. She has no recourse if she doesn’t like her wage to ask for more. They will go to another undocumented worker or have her deported. Her circumstances make her their slave.

(L to R): Soorro Santiago, Vanessa Aspillaga, ‘Mojada,’ written by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

All the general details of Medea, Jason and Acan, Tita relates to the audience chorus-like in a humorous narrative in which she pines for the old country and identifies the difference between the old ways and the inferior American lifestyle. Having been sold to take care of Medea since her mother died as a baby, Tita acknowledges her servile position, but reinforces her authority as a healer who has taught Medea everything she knows. Tita loves Medea who is her obligation. But she fears for her as an innocent and questions Medea’s blind loyalty to Jason whom she believes is not worthy of Medea’s trust. Tita is not only a healer, she is telepathic and she sees what Medea refuses to recognize because if she does, all that Medea has experienced to get to America is in vain, above all the pain and torment she endured on the trip and the misery she feels as an outsider who fits in nowhere in except in Jason’s arms and Acan’s reliance on her.

The arc of development jolts forward after we meet Jason and note how Medea and Jason greet each other, with the calls of the guaco, a bird that lives in the southwest. Their cries to each other are haunting and beautiful. We recognize the bond between them that is ethereal and powerful. Alex remains affectionate and loving to her as Alfaro diverges from Euripides’ classic tragedy in that their family which has been in the U.S. for about a year appears to be united and prospering. Jason is fearless in his desire to be someone and take Medea, Acan and Tita with him on this uplifted path to citizenship. He appears honorable and we assume theirs is the happy whole, until we discover the cracks in the foundation that earthquake and drive the family apart by the end of the play.

Alex Hernandez, Sabina Zúñiga Varela in ‘Mojada,’ by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

The cracks of the foundation are revealed in flashbacks. At one point Medea asks Jason to make love to her under the stars out in the open but she stops herself, and the tender Jason understands and is patient with her. In the extended flashback which Medea narrates, we discover how they struggled to make it to the border, but not before Medea is violated by Mexican soldiers. But that is not the worst that could have happened. Another young woman along the journey is not only gang raped, she is killed and dumped in an unmarked grave. The ordeals migrants go through seeking a better life for themselves is clarified dramatically during this vital segment without polemic or dogma. The ensemble’s acting during these scenes brings the audience to the edge of horror and beyond.

(L to R): Benjamin Luis Mcracken, Alex Hernandez, Sabina Zúñiga Varela, Socorro Santiago, in ‘Mojada,’ by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

It is Medea’s relationship with Jason that receives the most dynamic upturn in the development of the conflict which Alfaro gradually unravels as we glean the events from Medea’s perspective. Alfaro cleverly occludes the truth as Jason has obfuscated the reality of his personal circumstances to Medea. On the surface we only see that Jason chides her for not going out, and seeks her love and support for his working late nights for the family’s benefit. Even though gossipy comedic Luisa, a neighborhood vendor from Puerto Rico (vibrantly acted by Vanessa Aspillaga) intimates that she is glad her own husband is ugly because Jason’s good looks would be catnip to women, Medea laughs but doesn’t get the message. And the playwright gives no hint of deception until deep in the play so that when its revelation comes, we are shocked and devastated for her.

In a splendid and relevant turn for the culture he writes about, Alfaro shifts the conflict away from the aspect of revenge and justification for vengeance that the classic Euripides’ Medea emphasizes. In Mojado, Alfaro focuses on the bond between Jason and Medea, always as a loving one so that Jason’s betrayal lands like a bomb, and even then, Jason’s charm and sweet, urgent pleas almost convince Medea that he means well in his actions.

Benjamin Luis McCracken, Alex Hernandez,Sabina Zúñiga Varela, Socorro Santiago in ‘Mojada,’ by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

Medea’s true enemy is “the other woman” who is Jason’s wealthy boss Pilar (the forceful, slyly arrogant Ada Maris) who has turned her life into the success that Jason intends for himself. Pilar represents all that is noxious about immigrants who embrace the “American Dream,” assimilate and lose their souls to the pursuit of power and money. They become even more treacherous and corrupt than the dolorous white citizens who have been in the country for generations, some of whom have failed and refuse to pick themselves up but instead, blame the migrants for stealing jobs that their own lack of effort would never “lower” them to take, for they are too “superior” to do such labor. This notion abides sub rosa as we watch Pilar and Jason discuss business and note the tremendous industry that Pilar, Jason and Medea embody in their diligence and effort to make money and prosper. Undocumented migrants are synonymous with an incredible almost Puritan work ethic in this play. It is a truism that partisan politics to tickle the ears of the dolorous white supremacists turn on its head.

Pilar comes to diner and reminds Medea that she is staying in one of Pilar’s many houses. Pilar implies she is to be appreciated for not charging Medea fees for making the home into a sweat shop. She infers that it is only her reliance on Jason whom she intends to promote who deflects Pilar from taking a percentage of the money Medea makes. Again, the theme of the exploitation and predation of immigrant bosses who have “made it” taking advantage of undocumented migrant brothers’ and sisters’ industry and resourcefulness is brought to the fore.

When Pilar greets Acan with affection that reveals they have been together a number of times, Medea still remains blind. It is only when Jason reveals that he has married Pilar does Medea begin to understand the forces ranging against her. Medea and Jason never married. Medea believes their union is a spiritual force that would keep them together forever. A marriage paper for their life in Mexico was not necessary; they are bonded by their love and the fruit of their union, Acan. However, in America, legality is paramount so that their spiritual union is nullified by the absence of a piece of paper. The crass American values of money, power, materialism over spirituality, loyalty and love overcome Medea’s hope of survival. Her only way out of the misery and desperation Pilar and the corrupted Jason have bestowed on her as her fate is to take the only power she has left and use it.

(L to R): Sabina Zúñiga Varela, Ada Maris, Alex Hernandez in ‘Mojada,’ by Luis Alfaro, directed by Chay Yew (Joan Marcus)

In the incredible scene between Pilar and Medea, all of the undercurrents of a woman used to demanding her own way crashes into the innocent Medea’s consciousness. Pilar’s rivalry with this woman who is still loved by her man is acute. It is either Medea or her and unless Medea “gets lost” she will have her deported. The choice for her is no choice. An even more dire fate awaits Medea in Mexico in her home town.

Alfaro has written an amazing play referencing the classical tragedy. He has adopted his work to the Mexican/Latino culture and in so doing expertly gives us an appreciation for what immigrants endure for a better life. Additionally, we empathize because his work covers timeless themes about the powerless vulnerability of migrants like Medea/la mojada. He spins out the familiar tale but enhances it with great depth of feeling so that his protagonist (spoiler alert) restores her own honor and delivers herself to freedom by her acts which proceed more from desperation and sorrow than vengeance. She empowers herself through suicide, something that the sorceress Medea would never contemplate. But in la mojada’s choice there is dignity and sanctity, but at great cost. And at the last moments which are breathtaking she calls out with the cry of the guaco from the realm of spirit. And the response is her tragedy and fall from grace.

From the performances to the authentic, realistic sets and Chay Yew’s fine directorial choices, Mojada is Alfaro’s monumental vision for our times through the lens of Euripides powerful tragedy Medea. In effecting his version Alfaro reveals the great nobility and honor in those who seek to evolve to a different life in another culture, often not completely understanding that the life they seek is filled with corruption, devastation and dishonor. However, to not try is worse. To remain and never know or never learn is naive and a submission to fear and death. The greatness of Alfaro’s character Medea is in her attempt to hold on to the little health/innocence she has and endure. When evil threatens to overwhelm her and her family completely, she defends herself in the only way she knows how. And we are uplifted and sorrowed for her choice.

(L to R): Alex Hernandez, Sabina Zúñiga Varela, Benjamin Luis McCracken, Socorro Santiago (Joan Marcus)

Kudos goes to the creative team for their fine evocation of the family’s lifestyle through minimalism: Arnulfo Maldonado (Scenic Designer) Haydee Zelideth (Costume Designer) David Weiner (Lighting Designer) Mikhail Fiksel (Sound Designer) Stephan Mazurek (Projetion Designer) Earon Chew Nealey (Hair Style Consultant & Wig Designer) Unkledaves Fight0House (Fight & Intimacy Director).

Mojada runs 1 hour 45 minutes without an intermission at the Public Theater on Lafayette Street until 11 August. Run, do not walk to see this memorable production. For tickets and times CLICK HERE.

‘Ain’t No Mo,’ A Searing, Edgy, Sardonic, Magnificent Production at The Public

(L to R)” Fedna Jacquet, Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Marchant Davis, Simone Reccasner, Crystal Lucas-Perry in ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ written by Jordan E. Cooper, directed by Stevie Walker-Webb (Joan Marcus)

Aint’ No Mo by Jordan E. Cooper directed by Stevie Walker-Webb is the most cutting edge, maverick and sterling production I’ve seen this year at The Public Theater. It is a must-see for its hysterical humor, black satire, superb “over-the-top” performances and jaw-dropping, brilliant writing by the playwright whom I cannot praise enough for his startling wake-up call to citizens in this nation that faces, a constitutional crisis.

Cooper with the assistance of the sharp direction and lightening, comedic pacing of Stevie Walker-Webb who shepherds the electric, moment-to moment actors, lays bare themes about black Americans attempting to survive in the medium of white oppression, a condition which began when the first slave ship in 1619 offloaded its precious cargo to the lands we now refer to as the United States. Through vignettes exemplifying black characters who REPRESENT a variety of socio-economic and cultural identities that make up black American society today, Cooper, Walker-Webb and the versatile actors portray the alienation, dislocation and terrorization black individuals confront daily based on the color of their skin because of institutionalized racism, whether they acknowledge it or not.

Though the playwright satirizes black culture and the sardonic humor is exceptional, underlying all of the vignettes is the ubiquity of a fascist system that destroys or chips away through incipient attenuation black citizens’ rights, freedoms, talents, hopes, legacies and praise for black contributions to the goodness of our society. The cultural blessings of black identity reside in every area one can think of; they are an indelible part of our society and culture’s music, scientific research, dance, inventive creations and much more. But why are blacks still facing record incarceration, economic injustice, legal injustice, housing discrimination, job discrimination, educational discrimination, killings by racist law enforcement who are not held accountable and more?

Jordan E. Cooper in ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, written by Jordan E. Cooper, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

These inequalities born of white, male, privilege fascism, citizens must take to heart and understand regardless of skin color, especially if one is not black. Indeed, black American treatment in the culture serves to note the health of the society. It is like the canary in the coal mine. For a time around the decades up to the turn of the 20th century, it looked like maybe the canary was breathing. When Obama became president, the canary seemed stronger. But things didn’t turn out as expected. And now, the canary is croaking out its death song.

Cooper’s play exemplifies this with incredible power. It is a warning for all in the culture that we are very sick and it is especially egregious for black Americans. Those ethnicities who have their eyes open (not the KKK, the white supremacists, racist law enforcement, neo Nazis, the Trumpist administration and supporters, the Federalist Society and ultra-right wing think tanks who use race to divide and scoop up political power) are subject in a different way to the fascism that rides roughshod over black Americans.

Where fascist controllers are concerned, they will divide and conquer through racial hatreds so that ultimately all suffer under a horrible cultural-economic ethos where suffering becomes a matter of degree. And blacks are sacrificed in a blood letting that makes all guilty, unless they work fervently to stop it.

(L to R): Fedna Jacquet, Ebony Marshall-Oliver in ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, written by Jordan E. Cooper (Joan Marcus)

The greatness of this production which has not one “white” (an irony in itself since many “whites” don’t know their own racial history which includes African-American blood) person in it, concerns black perspectives about having to “get along” and survive in a “white privilege” culture. In effect, black Americans don’t “get along” very well (an understatement). And after the Obama administration ended in a hellishness for black Americans, the Trump election and current white supremacist administration has given rise to another holocaust.

With the empowerment of the KKK and white supremacy under Trump, where do blacks stand? Should they leave a country which has in some states reverted to voting violations reminiscent of the Jim Crow South? The question pervades this amazing and thought-provoking production from its powerful beginning to its riveting ending.

The production begins in a black church on the eve of the election of President Obama in 2008 during the funeral for Brother Righttocomplain. The Pastor leads the hopeful to believe that under Obama, a black president, finally things will begin to improve, and there will be “No Mo” of the oppression, killing and racial-based institutional abuse blacks have experienced.

However, at the end of the church service, we hear gunshots and see flashing red lights symbolizing more cops stopping blacks and killing them unjustly. And we hear in a voice over some of the black abuses that happened during Obama’s presidency, i.e. the Flint Water Crisis, the deaths of Travon Martin, Sandra Bland and scores of others. The unjust murders of many blacks at the hands of law enforcement continue. Obama did what he could but the death and destruction of black people and black identity in various forms is “alive and well.”

(L to R): Simone Recasner, Crystal Lucas-Perry, ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, written by Jordan E. Cooper (Joan Marcus)

Cooper then steps into the future. The horror of Trump’s election has resulted in an evacuation of all blacks in the US. Peaches (a wonderful job by Cooper) is a flight attendant on African American airlines and she is responsible for checking in passengers on the flights to African countries for free; it is a form of reparations. Blacks must leave and give up all they have known here, or they will be transmogriphied into whites. All traces of their blackness, culture, identity will be obliterated and they will have to start anew in Africa. Cooper establishes the play’s development with three Peaches’ segments during which thousands of blacks are checked onto their flights so that there will be no blacks left in America.

In between the flights taking off, Cooper relays vignettes of various black individuals being confronted with the decision of staying and losing their black ethos or leaving. In the “Circle of Life” vignette, hundreds of black women line up for abortions; they would rather kill their children then see them in prison or “die while black” at the hands of law enforcement in the US. How Cooper dramatizes this (NO SPOILER ALERT HERE) is superb. However, the news of the eviction letter is just being received for these women They will have to make their decision quickly because the planes are leaving.

In the next vignette, a reality show entitled “Real Baby Mamas of the South-Side,” Cooper confronts the memes of what black identity means. It is a humorous and drop-dead serious send-up of black reality shows which exploit the idea of “being black” from a profit-motive angle.

Marchant Davis, Fedna Jacquet in ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, written by Jordan E. Cooper, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

During this segment as he does with others, the playwright touches upon many examples of oppressive destruction of black identity and the internalization of the destruction as blacks attack themselves and each other’s confidence in their “blackness.”

For example nullification of black identity exists through excoriation of the darkness of one’s skin color and the naturalness of one’s hair. “The lighter the skin, the better” is a reality blacks have had to deal with because of white fascist physical mores. The trend has morphed over the decades into a perverse reverse. Other ethnic groups including whites have embraced the “black ethos” in a perverse acceptance of only the superficiality of “being black” without realizing any of the horrific sacrifices blacks have made over their 400-year history in this nation.

Cooper takes this notion and puts it on steroids during the hysterical, satiric “Real Baby Mamas of the South-Side.” One of the characters (Rachonda-her real name is Rachel) is going through transracial treatments to become black. When she is called out on it by Tracy, Kendra and Karen, she reveals that she has no clue about black American sacrifices and and just wants to ride the current wave of black female “cool” generated by Michelle Obama.

This becomes so obnoxious and Rachonda so overweening in exrpessing the “right” to be who she wants, the hypocrisy for the real black women is overwhelming. All fight, a boon for reality TV’s exploitation. The attack on each other is symbolic. It is a tragic outcome of internalizing the “whiter is better” cultural mores turned on its head. We are ironically reminded how divide and conquer is a tactic of the dominant, white, privilege culture.

(L to R): Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Crystal Lucas-Perry in ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ written by Jordan E. Cooper, directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, Public Theater (Joan Marcus)

Interestingly, the real black women leave to join the thousands who are evacuating to Africa. Of course Rachel (who is white) never gets the notification to evacuate. The irony is that in attempting to become transracial she will never be black “cool.”

In the remaining vignettes, Cooper reveals a wealthy bourgeois black family who is covering over their black identity symbolized by the character “Black” (dressed like a slave) who their father kept in the basement out of fear. Because he dared to have his own business, the KKK nearly lynched their father. As a result, he suppressed his “blackness” and assimilated/internalized white cultural mores while suppressing his “blackness” by chaining up Black in the basement (psychological suppression).

It is an incredible vignette, both sardonic and sober in its revelation that to survive, blacks have internalized white cultural values to their own destruction. By adopting the”white” ethos by being the proud bourgeois class (nullifying their real selves/souls) they have trampled all those who have shed blood to advance the hope of achieving civil rights, equal opportunity and justice overcoming institutional racism.

As the family attempts to have an elegant dinner and discuss whether to go to Africa, Black comes up from the basement bursting on the scene. Black, representing everything about the family’s identity that they wish to eradicate (having internalized the white supremacy values) is a horror to them. They end up killing Black themselves for they do not want to be associated with being black. They have wealth and status and live in a white neighborhood; they are deluded they have made it in the oppressive culture that has destroyed their being.

Indeed, the theme is clear. An oppressive fascist culture has as its most horrific tactic: get blacks to destroy the finest traits about them, their blackness. Without that blackness, they embody the worst of the fascist “master race.” They genocide their own and themselves..

Cooper also identifies the black, female prison population in a very powerful scene. When freedom is posited, one of the prisoners, Blue, in great fear and rage from all the abuse of her past nearly creates a situation where she messes up her chances for freedom and is killed (or never makes the plane and is transmogrified). How Cooper ends this vignette and the last one when Peaches also goes to join those evacuating the US, are memorable scenes. They leave the audience in complete shock.

Jordan E. Cooper, ‘Ain’t No Mo,’ directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, written by Jordan E. Cooper (Joan Marcus)

This superb production is a crucifying indictment of the nullification/annihilation of black Americans through identity confusion and racist oppression via various institutions in the United States. It is even more prevalent today under Trumpism in its blatant constitutional violations, gerrymandering, lies, destroying ballots and Trump’s sanctioning of the Russians helping elect him. (He denies this still, though the Mueller Report evidence proves the Russians meddled and then that Trump covered it up and obstructed justice). All of these segments hit the bulls-eye with mind-blowing truthfulness that makes one laugh and cry at the same time.

The themes are unmistakable. The sub rosa genocide of black Americans will continue unless we work together to stop it. Regardless, black Americans have made magnificent contributions and are the backbone of our progress. No one culture and class should dominate; that is the greatest myth and whether or not whites acknowledge that this is a lie, nevertheless, is a lie. The truth is apparent.

Sadly, if black women question having children because they fear giving them up to shootings and jail terms, then where is the hope? Are the strides taken up to this point in time hope-filled enough to continue in the face of the new fascism and white supremacy that is just plain in your face and denies that it is in your face? The play raises these questions for us to consider and answer with advocacy and action.

This marvelous production is an experience. Above all it is a reminder that we are together in this culture, striving to prosper. If we don’t work for all of us, then we can’t work for any of us. This is especially so against an administration that only bows to its own agenda and money men.

Praise go to these actors: Fedna Jacquet, Marchant Davis, Simone Recasner, Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Crystal Lucas-Perry and Jordan E. Cooper as Peaches. Kudos go to Kimie Nishikawa (Scenic Design), Montana Levi Blanco (Costume Design) Adam Honore (Lighting Design) (Emily Auciello (Sound Design) Cookie Jordan (Hair, Wig, Makeup Design).

Ain’t No Mo runs with no intermission until 5 May. Don’t miss this incredible, “in-your-face” production. You will be glad you saw something as novel and profound and wonderfully performed as you will see. There is NOTHING like it around! For tickets go to the website by CLICKING HERE.