Blog Archives

‘Chinese Republicans’ a Sardonic Look at Chinese Women and the Glass Ceiling

A cross section of how Chinese American women have fared in the corporate world is the engaging subject of Alex Lin’s ironic, humorous and ultimately devastating play Chinese Republicans. Directed by Chay Yew, the well-honed production examines personal sacrifice, identity conflicts, and nuanced discrimination (gender, age, cultural). Currently, Chinese Republicans runs at the Roundabout, Laura Pels Theare, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre until April 5, 2026.

The playwright spins a complex dynamic about Chinese American corporate working women. Yew expertly unfolds the complications among four women of different generations, including one immigrant, working to get her citizenship. During meetings designed to encourage affinity but which actually stir resentments and competitiveness, each of the characters reveals the struggle they face to break the glass ceiling, competing against their less qualified male counterparts. Though the story is unfortunately all too familiar, Lin spikes the interactions with an original, darkly funny approach that resonates with currency.

The production takes off by introducing us to four female suits who work at various upper level positions at Friedman Wallace, as they gather for their “affinity luncheon,” where they meet once a month at a Chinese restaurant. We note ambition, assertiveness and edginess which might as readily be exhibited by any male power-player succeeding in a tough environment. However, these women must obviously work much harder for their success because of internal biases against them culturally as women, and especially as Chinese women. Lin and Yew dance artfully around this gender debility by focusing on cultural elements and details. This strengthens the irony and themes while instructing the audience on elements about the Chinese culture they may not know.

First and most preeminent with experience and knowledge to instruct the younger suits is Phyllis (Jodi Long). She holds little back and uses her irony as a weapon. Ellen, (Jennifer Ikeda), Phyllis’ mentee, has sacrificed having children for her position and plans on becoming partner. Iris (Jully Lee), an immigrant who speaks four dialects, chides the others, especially Ellen on their bad Mandarin and losing touch with their Chinese identity. Lastly, Katie (Anna Zavelson) is the youngest and newest member of the group. Confident and positive about her recent promotion, Katie enthusiastically intones she is excited about their “making a difference.” Then she proclaims, “Come on Asian queens.”

From this luncheon onward, Lin and Yew prove the difficulty for each of the characters to be “Asian queens” in their workplace or their personal lives. Mostly the scenes take place at the restaurant as neutral ground with the exception of the game show farce when Iris ironically shreds Ellen, Phyllis and Katie’s ambitions with irony as part of a fever dream turned nightmare. The side scene after Katie does a turn around and evolves into an advocate for unionizing Friedman Wallace is funny, as she stands in front of the building pumping up a labor rat while the others watch her from the conference room at Friedman Wallace in shock and horror.

How and why Katie reverts to an anti-Republican unionizer from “gun-ho” Asian queen Republican in all its glory involves the corrupt male culture of Friedman Wallace, to discriminatory street violence against Phyllis, to Iris’ immigration hell, to sexual harassment and much more. However, we learn a few twists and turns about each of the characters that add to our admiration of these highly competent women who have endured and suffered nobly, knowing in their bones that not only are the odds stacked against them to ever be at the top, they have strived and sacrificed to what end? A sea of regrets?

The ensemble is uniformly superior. Each portrays their characters with authenticity and a no holds barred approach. As a result the concluding revelations land with poignancy and a powerful kick. The double irony of the evolving meaning of being a Republican is tragic, considering the current face and brand of the MAGA party. Lin neatly slips this information about being Republican into Katie’s development from corporate martinet to human being with a conscience. It’s a reminder to history buffs and salient information for others that political labels are meaningless.

Chinese Republicans fires on all levels of theatricality and spectacle, adhering to Yew’s minimalist, unadorned vision for Lin’s play which focuses on character and themes. Wilson Chin (set design), Ania Yavich (costume design) and other creatives present an attractive backdrop which lends itself to disappearing so the actors are able to live onstage and emotionally, profoundly impact the audience.

https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2025-2026-season/chinese-republicans

‘The Honey Trap,’ Irish Rep’s Acclaimed Production Returns

Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Kara Young and Nicholas Braun Fine-Tune Their Performances in ‘Gruesome Playground Injuries’

What do people do when they have emotional pain? Sometimes it shows physically in stomach aches. Sometimes to release internal stress people risk physical injury doing wild stunts, like jumping off a school roof on a bike. In Rajiv Joseph’s humorous and profound Gruesome Playground Injuries, currently in revival at the Lucille Lortel Theater until December 28th, we meet Kayleen and Doug. Two-time Tony Award winner Kara Young and Succession star Nicolas Braun portray childhood friends who connect, lose track of each other and reconnect over a thirty year period.

Joseph charts their growth and development from childhood to thirty-somethings against a backdrop of hospital rooms, ERs, medical facilities and the school nurse’s office, where they initially meet when they go to seek relief from their suffering. After the first session when they are 8-year-olds, to the last time we see them at 38-year-olds at an ice rink, we calculate their love and concern for each other, while they share memories of the most surprising and weird times together. One example is when they stare at their melded vomit swishing around in a wastepaper basket when they were 13-year-olds.

How do they maintain their relationship if they don’t see each other for years after high school? Their friends keep them updated so they can meet up and provide support. From their childhood days they’ve intimately bonded by playing “show and tell,” swapping stories about their external wounds, which Joseph implies are the physical manifestations of their soul pain. After Doug graduates from college, when Doug is injured, someone tips off Kayleen who comes to his side to “heal him,” something he believes she does and something she hopes she does, though she doesn’t feel worthy of its sanctity.

Joseph’s two-hander about these unlikely best friends alludes to their deep psychological and emotional isolation that contributes to their self-destructive impulses. Kayleen’s severe stomach pains and vomiting stems from her upbringing. For example in Kayleen’s relationship with her parents we learn her mother abandoned the family and ran off to be with other lovers while her father raised the kids and didn’t celebrate their birthdays. Yet, when her mother dies, the father tells Kayleen she was “a better woman than Kayleen would ever be.” There is no love lost between them.

Doug, whose mom says he is accident prone, uses his various injuries to draw in Kayleen because he feels close to her. She gives him attention and likes touching the wounds on his face, eyes, etc. Further examination reveals that Doug comes from a loving family, the opposite of Kayleen’s. Yet, he may be psychologically troubled because he risks his life needlessly. For example, after college, he stands on the roof of a building during a storm and is struck by lightening, which puts him in a coma. His behavior appears foolish or suicidal. Throughout their relationship Kayleen calls him stupid. The truth lies elsewhere.

Of course, when Kayleen hears he is in a coma (they are 28-year-olds), after the lightening episode, she comes to his rescue and lays hands on him and tells him not to die. He recovers but he never awakens when she prays over him. She doesn’t find out he’s alive until five years later when he visits her in a medical facility. There, she recuperates after she tried to cut out her stomach pain with a knife. She was high on drugs. At that point they are 33-year-olds. Doug tells her to keep in touch, and not let him drift away, which happened before.

Joseph charts their relationship through their emotional dynamic with each other which is difficult to access because of the haphazard structure of the play, listing ages and injuries before various scenes. In this Joseph mirrors the haphazard events of our lives which are difficult to figure out. Throughout the 8 brief, disordered, flashback scenes identified by projections on the backstage wall listing their ages (8, 23,13, 28, 18, 33, 23, 38) and references to Doug’s and Kayleen’s injuries, Joseph explores his characters’ chronological growth while indicating their emotional growth remains nearly the same, as when we first meet them at 8-years-old. In the script, despite their adult ages, Joseph refers to them as “kids.”

Toward the end of the play via flashback (when they are 18-year-olds), we discover their concern and love for for each other and inability to carry through with a complete and lasting union as boyfriend and girlfriend. When Doug tries to push it, Kayleen isn’t emotionally available. Likewise when Kayleen is ready to move into something more (they are 38-year-olds), Doug refuses her touch. By then he has completely wrecked himself physically and can only work his job at the ice rink sitting on the Zamboni.

Young and Braun are terrific. Their nuanced performances create their characters’ relationship dynamic with spot-on authenticity. Acutely directed by Neil Pepe, we gradually put the pieces together as the mystery unfolds about these two. We understand Kayleen insults Doug as a defense mechanism, yet is attracted to his self-destructive nature with which she identifies. We “get” his protection of her because of her abusive father. One guy in school who Doug fights when the kid calls her a “skank,” beats him up. Doug knows he can’t win the fight, but he defends Kayleen’s name and reputation.

The lack of chronology makes the emotional resonance and causation of the characters’ behavior more difficult to glean. One must ride the portrayals of Young and Braun with rapt attention or you will miss many of Joseph’s themes about pain, suffering and the salve for it in companionship, honesty and love.

In additional clues to their character’s isolation, Young and Braun move the minimal props, the hospital beds, the bedding. They rearrange them for each scene. On either side of the stage in a dimly lit space (lighting by Japhy Weideman), Young and Braun quickly fix their hair and don different costumes (Sarah Laux’s costume design), and apply blood and injury-related makeup (Brian Strumwasser’s makeup design). In these transitions, which also reveal passages of time in ten and fifteen year intervals, we understand that they are alone, within themselves, without help from anyone. This further provides clues to the depths of Joseph’s portrait of Kayleen and Doug, which the actors convey with poignance, humor and heartbreak.

Gruesome Playground Injuries runs 1 hour 30 minutes with no intermission through 28 December at the Lucille Lortel Theater; gruesomeplaygroundinjuries.com.

Lesley Manville and Mark Strong are Mindblowing in ‘Oedipus’

Just imagine in our time, a leader with integrity and probity, who searches out the truth, no matter what the cost to himself and his family. In Robert Icke’s magnificent reworking of Sophocles’ Oedipus, currently at Studio 54 through February 8th, Mark Strong’s powerful, dynamically truthful Oedipus presents as such a man. Likewise, Lesley Manville’s lovely, winning Jocasta presents as his steely, supportive, adoring help-meet. Who wouldn’t embrace such a graceful couple as the finest representatives to govern a nation?

Sophocles’ classic Greek tragedy, that defined the limits of the genre and imprinted on theatrical consciousness the idea that a tragic hero’s hubris causes his destruction, evokes timeless verities. In his updated version, Icke, who also directs, superbly aligns the characters and play’s elements with today’s political constructs. Icke retains the names of the ancient characters. This choice spurs our interest. How will he unravel Sophocles’ amazing Oedipus tragedy, especially the conclusion?

Cleverly, he presents Oedipus as a political campaigner of a fledgling movement that over a two-year period gains critical mass. The director reveals Oedipus’ backstory in a filmed speech to reporters on the eve of the election. The excellent video design is by Tal Yarden.

During his speech Oedipus goes off book and makes promises. Though his brother-in-law Creon (the fine John Carroll Lynch) tries to stop him, proudly Oedipus shows himself a man of his word. He galvanizes the crowd when he states he will expose the lies of his opponents. Not only will he reveal his birth certificate (an ironic reference to President Obama), he will investigate the mysterious death of Laius. The former leader from decades ago married Jocasta when she was a teenager. After Laius’ death, Oedipus meets and marries Jocasta despite their age difference. Over the years they raise three children: Antigone (Olivia Reis), Eteocles (Jordan Scowen) and Polyneices (James Wilbraham).

How has Oedipus become the people’s candidate? Without ties to the political system, he speaks a message of reform and justice. Indeed, he will override the corrupt, derelict power structure. Former leaders served their rich donors and let the other classes suffer. Oedipus runs on a mandate of equity and change.

After Oedipus’ speech, the curtain opens to reveal the campaign headquarters that staff gradually dismantles as the campaign phase ends. To signify the next phase the countdown clock, placed conspicuously in scenic designer Hildegard Bechtler’s headquarters, ticks away the seconds down to the announcement of the winner. As the clock ticks toward zero (an ironic symbol), the contents of the campaign war room are removed like the peeling of an onion to its core. As the destined announcement of the winner nears, gradually, the revelation of Oedipus’ true identity happens. Icke has synchronized both concurrently.

Icke’s anointed idea to shape Oedipus as a newbie politician, whose actions and words are singularly unified in honesty, resonates. He represents the iconic head of state we all yearn for and believe in, forgetting leaders are flesh and blood. Of course Icke’s flawed tragic hero, like Sophocles’ ancient one, results in Oedipus’ prideful search for the truth of his origin story and Laius’ cause of death.

Oedipus’s determination is spurred by the cultist future-teller Teiresias (the superb Samuel Brewer). His authoritative and relentless drive to prove Teiresias wrong, despite warnings from Creon and Jocasta, shows persistence and courage, positive leadership qualities. On the other hand, Oedipus doesn’t realize his search has a dark side and his persistence is stubbornness prompted by a prideful ego. This stubbornness causes his destruction. His pride leaves no way out for him but punishment.

Because the truth is so horrid, Strong’s Oedipus can’t suffer himself to cover it up. In searching to validate his true self, he discovers the flawed human that Teiresias proclaims. Indeed, he is more flawed than most. He is lurid; a man who killed his father, married his mother, and had three children born out of love, lust and incest. He can never be the leader of the nation. He must hold himself accountable after he sees his debased true self. How Mark Strong effects Oedipus’ self-punishment is symbolic genius. Clues to Jocasta’s end are sneakily tucked in earlier.

Because of Icke’s acute shepherding of the actors, and the illustrious performances of Manville, Strong and Brewer, with the cast’s assistance, we feel the impact of this tragedy. The love relationship between Jocasta and Oedipus, drawn with two passionate scenes by Manville and Strong, especially the last scene, after they acknowledge who they are with one, long, silent look, devastates and convicts.

Those who know the story feel a confluence of emotions at the irony of mother and son lustily loving and pursuing their desire for each other off stage, while Oedipus delays speaking to his mother Merope (Anne Reid). Manville and Strong are extraordinary. Both actors convey the beauty, the wildness, the uniqueness and enjoyment of their characters’ love, that is unlike any other.

In the last scene when Strong and Manville untangle from their hot grip, clinging to each other then letting go, they acknowledge their characters’ unfathomable and great loss. Manville’s Jocasta crawls away to reconcile the enormity of what she has done. In her physical act of crawling then getting up, we note that fate and their choices have diminished their majestic grace. Their sexual likeness to animals, Oedipus ironically referenced earlier with family at the celebration dinner. Through the physical staging of the final sexual scene, Icke recalls Oedipus’ earlier comparison.

As a meta-theme of his version Icke reminds us of the importance of humility. The more humanity presents its “greatness,” the more it reveals its base nature.

All the more tragedy for Oedipus’ supporters and the unnamed country. Because fate catches up with him and conspires with him to cut off his acceptance of the position he rightfully won, the nation loses. All the more sorrow that the truth and his honest search is what Oedipus prizes, even more than his love for Manville’s Jocasta, the brilliant, equivalent match for Strong’s Oedipus.

Rather than live covertly hiding their actions, both Oedipus and Jocasta hold themselves accountable with a fatalistic strength and nobility. Initially, we learn of her strength as Jocassta tells Oedipus about her experience with the evil Laius (a reference to current political pedophiles and rapists). We see her strength in her self-punishment. Likewise, Oedipus’ strength compels him to face his deeds where cowards would cover up the truth, step into the position and govern autocratically censoring and/or killing their opponents who would “spill the beans.” Oedipus is not such a man. It is an irony that he is a moral leader, but is unfit to lead.

Icke’s masterwork and Manville and Strong’s performances will be remembered in this great production, filled with ironic dialogue about sight, vision, blindness and comments that allude to Oedipus and Jocasta’s incestuous relationship and downfall. Those familiar with the tragedy will get lines like Jocasta’s teasing Oedipus, “You’ll be the death of me,” and her telling people she has four children: “two at 20, one at 23, and one at 52.”

Though I prefer Icke’s ending in darkness with the loud cheers of the supporters, I “get” why Icke ends Oedipus in a flashback. In the very last scene the date is 2023, the beginning of the end. We watch the excited Oedipus and Jocasta choose the rented space (the stripped stage) for their campaign headquarters. The time and place mark their disastrous decision which spools out to their destruction two years later. I groaned with Jocasta’s ironic comment, “It feels like home.”

Her comment resonates like a bomb blast. If Oedipus had not had the vision of himself as the ideal, righteous leader with truth at his core, the place where they are “at home” never would have been selected. Oedipus, a humble mortal, never would have run for high office.

Oedipus runs 2 hours with no intermission at Studio 54 though February 8. oedipustheplay.com.

‘The Other Americans,’ John Leguizamo’s Brilliant Play Targeting the American Dream Extends Multiple Times

After a long career in every entertainment venue from films, to TV, to theater, Broadway, Off Broadway, etc., the prodigious work by the exceptional John Leguizamo speaks for itself. Now, Leguizamo tackles the longer theatrical form in writing The Other Americans, extended again until October 24th at the Public Theater.

Superbly directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, the theatrical elements of set design, lighting, costumes speak to the 1990s setting and cultural nuances. The following creatives developed a smart, stylish representation of the Castro household (Arnulfo Maldonado-set design, Kara Harmon-costumes, Justin Ellington-sound, Lorna Ventura-choreography).

Perhaps Leguizamo’s play could be tweaked to tighten the dialogue. All the more to have it shine with blinding, unforgettable truths sounding the alarm for immigrants in this nation. If tightened a bit, the complex, profound play would land perfectly as the unmistakable tragedy it inherently is. However, in its current iteration, Leguizamo gets the job done. The powerful play with comedic elements resonates to our inner core as a nation of immigrants and especially for Latinos.

Clearly, Leguizamo’s characterizations and themes add to the canon of classics that excoriate and expose the corrupted myth of the American Dream as a lie fitted to destroy anyone who believes it. That immigrants make the sacrifices they do to embrace it, is the ultimate tragedy.

Nelson Castro (played exquisitely by John Leguizamo), born in Jackson Heights from Columbian ancestry, embraces the American Dream. His wife Patti (the amazing Luna Laren Velez), from her Puerto Rican heritage, not so much. Patti’s values lead to loving her family and friends with devotion. Daughter, Toni (Rebecca Jimenez), who will marry the solid but nerdy Eddie (Bradley James Tejeda), looks to fit in as a white woman. The younger Nick (Trey Santiago-Hudson) was like his dad and took advantage of others, fiercely competitive. However, an incident changed him forever.

As the play unfolds, Leguizamo deals with the central question. To what extent have the warped values of the predominant culture negatively impacted this Latino family? From his first speech on we note that these twisted values have lured Nelson. The ethos-scam to get ahead-guides Nelson like a veritable North Star. He uses “getting over” as the key reason to provide for his family. This excuse rots everything under his power.

For example, Nelson acts the part of the upwardly mobile success story who always has a deal on the table ready to go. The irony is not lost on us when Nelson hypes a deal with a real estate big wig. Meanwhile, the mogul lives off his reputation for ripping off minorities. Sadly, Nelson admires the mogul’s pluck and con abilities. He ignores how this can potentially harms Latinos.

Mirroring the sick culture and society that values money and material prosperity over people, Leguizamo’s tragic hero tries to wheel and deal to get ahead. Making bad decisions, he overextends himself. Meanwhile, he encourages Nick and Toni to follow his lead. His overweening pride as the patriarch drives him to assume the mantle of a power player. Indeed, the opposite is true. During the process that causes him to fail and lie about it, he compromises his integrity and family’s probity and sanctity. That he willfully blinds himself to the consequences of his beliefs and suppresses his intelligence and good will to fit in, is the final heart breaker.

As in the classic tragic hero, Nelson’s pride also dupes him into a psychotic circularity to believe he has no recourse. Of course he believes the wheels have been set in motion against him by the society’s bigotry and discriminatory values. He should recognize and reject the society that uplifts such values because they support doing whatever necessitates getting ahead. The entire rapacious structure promotes financial terrorism and, whenever possible, it must be rejected. However, Nelson can’t reject it because he can’t help himself from being seduced. Instead, he persists in a prison of his own making, digging his family grave, on a collusion course of self-destruction.

Sadly, he internalizes the society’s inhumanity and makes it his own, a self-hating Latino. Because he adopts this construct because he loathes his immigrant self, he tries to create a new identity apart from his inferior ancestry. Thus, he moves to Forest Hills away from Jackson Heights where he lived “like an immigrant” in a place where cockroaches multiplied.

Finally, as we watch Nelson struggle to assert this new identity in a flawed, indecent, racially institutionalized culture (represented by Forest Hills and what a group of kids did to his son in high school), Leguizamo’s play asserts an important truth for immigrants. Internalizing and adopting the culture’s corrupt, sick, anti-human values is not worthy of immigrants’ sacrifices. This theme is at the heart of Leguizamo’s play. In his plot development and characterizations Leguizamo reveals his tragic hero chases after prosperity and upward mobility. The incalculable loss of what results-losing what it means to be human-isn’t worth it. If one does not weep for Leguizamo’s Nelson at the play’s conclusion, you weren’t paying attention.

To exemplify his themes, Leguizamo uses the scenario of the Castros, an American Latino family. They move from the homey, culturally diverse Jackson Heights to the white, Jewish upscale, racist enclave of Forest Hills. At the outset of the play Nelson, a laundromat owner, awaits his son’s return from a psychiatric facility. Patti has cooked up her son’s favorite dishes. Not only does this reveal her care and concern for her son, her comments to Nelson show her nostalgia for the Latin foods and people of their original Jackson Heights neighborhood in Queens.

By degrees Leguizamo reveals the mystery why Nick was in a facility. Additionally, the playwright brilliantly explores the conflicts at the heart of this family whose parents put their stake in their children, chiefly son Nick to get ahead financially in the Castro business. To recuperate, the doctors partially helped Nick with medication and therapies.

However, on his return home months later, he still suffers and has episodes. Patti sees the change in his dislike of his old favorite foods (symbolic). Not only does he reject meat, he rejects Catholicism and turns to Buddhism. Because a girl he met at the facility influences him, he moves away from his Latin roots. Later, we learn he loves and admires her and they plan to live together. However, he doesn’t look at the difficulties of this dream: no money, no family support.

The family conflicts explode when Nick attempts to be truthful with his parents. In his conversation with his mother we learn the horrific details of the beating he received in high school, why it happened, and how it led to episodes in college. Wanting to move beyond this through understanding, Nick learns in therapy that he must talk to his father. Nelson refuses to acknowledge what happened, and becomes a stalemate to Nick’s progress.

Additionally, his doctor supports Nick’s getting out from under the family’s living arrangements. Inspired, Nick yearns to create a life for himself away from their control to be his own person. Ironically, he follows in his father’s footsteps wanting to create a new identify for himself. Yet, he can’t create this identity unless he confronts the truth of what happened to him in high school and talks to his father. Unless he understands the extremely complex issues at the heart of his father’s tragedy, they won’t move forward together. Nelson must understand that he hates his own immigrant being and has embraced sick, twisted corrupt values which he never should have pushed on his family.

Meanwhile, in a fight with Nelson, Nick demonstrates what may really be happening to him. Though he survived the high school beating with a baseball bat, he most probably suffers from what doctors have come to understand as TBI (traumatic brain injury). With TBI the individual suffers debilities both physically and emotionally. When Nelson questions the efficacy of the treatment Nick received from doctors who didn’t really know what was happening to Nick, Nelson is on the right track. But the science had to catch up to Nelson’s observations.

Meanwhile, the problems relating to Nick needing the right help from his parents and his doctors, Nelson’s financial doom and the future of this Latino family under duress are answered in a devastating, powerful conclusion.

There is no spoiler. Leguizamo elegantly and shockingly reveals this family as a microcosm of the ills of our culture and society. Additionally, he sounds the warning for immigrants. If they don’t recognize and refuse the twisted folkways of the “American Dream,” they may lose their self-worth and humanity for a for a lie.

The Other Americans runs 2 hours 15 minutes including an intermission at The Publica Theater until November 23, 2025. https://publictheater.org/theotheramericans

Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter carry Ted and Bill into the adventure of ‘Waiting for Godot’

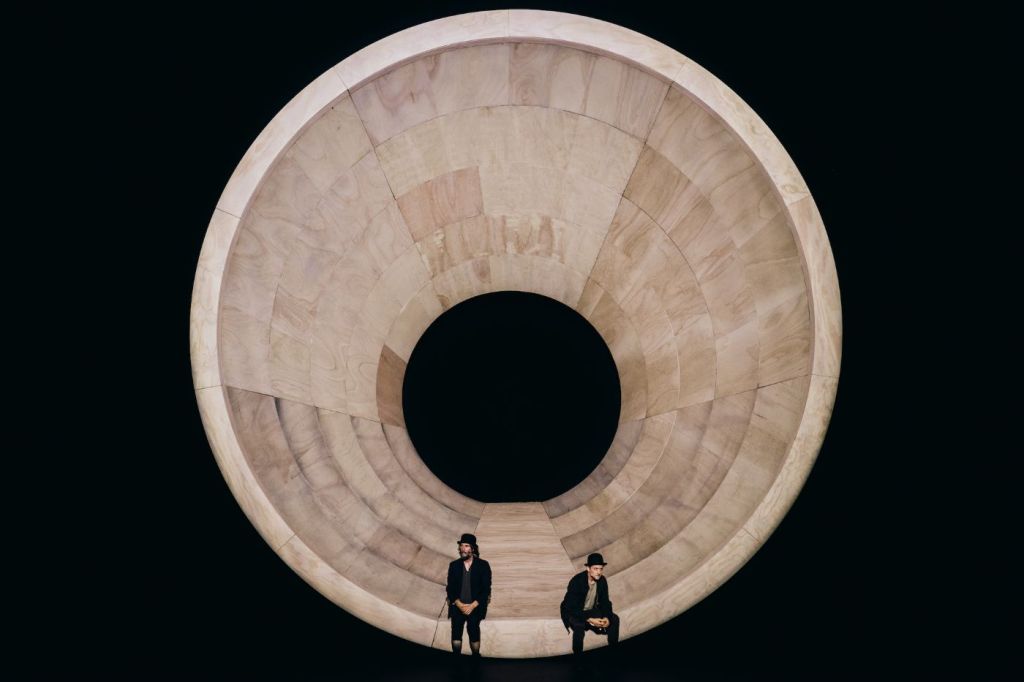

Referencing the past with Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure movie series, something has happened. Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), who long dropped their younger selves and reached maturity in Bill and Ted Face the Music (2020), have accomplished the extraordinary. They’ve fast forwarded to a place they’ve never been before in any of their adventures. An existential oblivion of uncertainty, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

There, they cavort and wallow in a hollowed out, megaphone-shaped, wind-tunnel (Soutra Gilmore’s clever set design). The gaping maw is starkly, thematically lighted by Jon Clark. Ben & Max Ringham’s sound design resonates the emptiness of the hollow which Winter’s Valdimir and Reeves Estragon fill up to the brim with their presence. And, among other things, Estragon loudly snacks on invisible turnips and carrots, and some chicken bones.

Oh, and a few others careen into their empty hellscape. One is a pompous, bullish, land-owning oligarch with a sometime southern accent, whose name, Pozzo, means oil well in Italian (a superb Brandon J. Dirden in a sardonic casting choice). And then there is his slave, for all oligarchs must have slaves to lord over, mustn’t they? Pozzo’s DEI slave in a wheelchair, seems misnamed Lucky (the fine Michael Patrick Thornton).

However, before these former likenesses of their former selves show up and startle the down-on-their luck Vladimir and Estragon, the two stars of oblivion wait for something, anything to happen. Maybe the dude Godot, who they have an arrangement with, will show up on stage at the Hudson Theatre. Maybe not. At the end of Act I he sends an angelic looking Boy to tell them he will be there tomorrow. A silent echo perhaps rings in the stillness of the oblivion where the hapless tramps abide.

Despite the strangeness of it all, one thing is certain. Bill and Ted are together again for another adventure that promises to be like no other. First, they’ve landed on Broadway, dressed as hobos in bowler hats playing clowns for us, who happily watch and wait for Godot with them. And it doesn’t matter whether they tear it up or tear it down. The excellent novelty of these two appearing live as Didi (Vladimir) and Gogo (Estragon), another dimension of Bill and Ted, illuminates Beckett.

Keanu Reeves’ idea to have another version of their beloved characters confront Samuel Beckett’s tragicomical questions in Waiting for Godot seems an anointed choice. It is the next step for these bros to “party on,” albeit with unsure results. However, they do well fumfering around in this hollowed out world, a setting with no material objects. The director has removed the tree, the whip, or any props. Thus, we concentrate on their words. Between their riffs of despair, melancholy, hopelessness and trauma, they have playful fun, considering the existential value of life. Like all of us, if they knew what circumstances meant in the overall arc of their lives, they wouldn’t be so lost.

Director Jamie Lloyd, unlike previous outings (A Doll’s House, Sunset Boulevard), keeps Beckett’s script without alteration. Why not? Rhythmic, poetic, terse, seemingly repetitive and excessively opaque, in their own right, the spoken words ring out, regardless of who speaks them. That the characters of Bill and Ted are subsumed by Beckett’s Didi and Gogo makes complete sense.

What would they or anyone do if there was no intervention or salvation as occurs fancifully in the Bill and Ted adventure series? They’d be waiting for salvation, foiled and hopeless about the emptiness and uselessness of existence without definition. Indeed, politically isn’t that what some in a nation of unwitting, passively oppressed do? Hope for salvation by a greater “someone,” when the only possibility is self-defined, self-salvation? How long does it take to realize no one is coming to help? Maybe if they help themselves, Godot will join in the work of helping them find their own way out of oblivion. But just like the politically passive who do nothing, the same situation occurs here. Godot is delayed. Didi and Gogo do nothing but play a waiting game.

From another perspective eventually unlike political passives they compel themselves to act. And these acts they accomplish with excellent abandon. They have fun.

And so do we watching, listening, wondering and waiting with them. Their feelings within a humorous dynamic unfold in no particular direction with a wide breadth of expression. Sometimes they want to hang themselves to end the frustration. Sometimes, bored, they engage in swordplay with words. Sometimes they rage. Through it all they have each other. And despite wanting to separate and go their own ways, they do find each other comforting. After all, that’s what friends are for in Jamie Lloyd’s anything is probable Waiting for Godot.

In Act I they are tentative, searching their memories for where they are and if they are. Continually, they circle the truth, considering where the one is who said they were coming. However, the situation differs in Act II because the Boy gave them the message about Godot.

In Act II they cut loose: chest bump, run up and down their circular environs like gyrating skateboarders seamlessly navigating curvilinear walls. By then, the oblivion becomes familiar ground. They relax because they can relax, accustomed to the territory. And we spirits out there in the dark, who watch them, become their familiar counterparts, too. Maybe it’s good that Godot isn’t coming, yet. They may as well while away the time. Air guitar anyone? Yes, please. Reality is what we make it. Above all, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. In the second act they don’t. After all, they could turn out like Pozzo and Lucky. So they do have fun while the sun shines, until they don’t and return right back to square one: they wait.

As for Pozzo and Lucky a further decline happens. In Act I Lucky gave a long, unintelligible speech that sounded full of meaning. In Act II Lucky is mute. Pozzo, becomes blind and halt, dependent upon Lucky to move. He reveals his spiritual and physical misery and haplessness by crying out for help. On the one hand, the oppressor caves in on himself via the oppression of his own flesh. On the other hand, he still exploits Lucky whom he leads, however awkwardly. The last shreds of his bellicosity and enslavement of Lucky hang by a thread.

Pozzo has become only a bit less debilitated than Lucky, whereas before, his identity commanded. Fortunately for Pozzo Lucky doesn’t revolt and leave him or stop obeying him. Instead, he takes the role of the passive one, while Pozzo still acts the aggressor, as enfeebled as he is. The condition happened in the twinkling of an eye with no explanation. Ironically, his circumstances have blown most of the bully out of him and reduced him to a pitiable wretch.

Nevertheless, Didi and Gogo acknowledge Pozzo and Lucky’s changes with little more than offhanded comments. What them worry? Their life-giving miracle happened. They have each other. It’s a congenial, permanent arrangement. After that, when the Boy shows up to tell them the “bad” news, that Godot has been delayed, yet again, and maybe will be there tomorrow, it’s OK. There’s no “sound and fury” as there is in Macbeth’s speech about “tomorrows.” We and they know that they will persist and deliver themselves and each other into their next clown show, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

If one rejects the comparison of this version of Waiting for Godot with others they may have seen, that wisdom will yield results. To my thinking comparing versions takes the delight out of the work. The genius of Beckett is that his words/dialogue and characters stand on their own, made alive by the personalities of the actors and their choices. I’ve enjoyed actors take up this great work and turn themselves upside down into clown princes. Reeves and Winter have an affinity and humility for this uptake. And Lloyd lets them play, as he damn well should.

In the enjoyment and appreciation of their antics, the themes arrive. I’ve seen greater and lesser lights in these roles. Unfortunately, I allowed their personalities and their gravitas to distract me and take up too much space, crowding out my delight. In allowing Waiting for Godot to settle into fantastic farce, Lloyd and the exceptional cast tease out greater truths. These include the indomitably of friendship; the importance of fun; the tediousness of not being able to get out of one’s own way; the uselessness of self-victimizing complaint; the vitality and empowerment of self-deliverance, and the frustration of certain uncertainty.

Waiting for Godot runs approximately two hours five minutes with one intermission, through Jan. 4 at the Hudson Theatre. godotbroadway.com.

‘The Weir’ Review: Drinks and Spirits in a remote Irish Pub

Conor McPherson’s The Weir currently in its fourth revival at Irish Repertory Theatre has evolved its significance for our time. It captures the bygone Irish pub culture and isolated countryside, disappeared by hand-held devices, a global economy and social media. Set in an area of Ireland northwest Leitrim or Sligo, five characters exchange ghostly stories as they drink and chase down their desire for community and camaraderie. Directed with precision and fine pacing by Ciarán O’Reilly, The Weir completes the Irish Rep’s summer season closing August 31st.

Charlie Corcoran’s scenic design of the pub with wooden bar, snacks, bottles, a Guinness tap and heating grate is comfortable for anyone to have a few pints and enjoy themselves at a table or nearby bench. With Michael Gottlieb’s warm, inviting lighting that enhances the actors’ storytelling, all the design elements including the music (Drew Levy-sound design), heighten O’Reilly’s vision of an outpost protective of its denizens and a center of good will. It’s perfect for the audience to immerse itself in the intimacy of conversation held in non-threatening surroundings.

On a dark, windy evening the humorous Jack drops in for drinks as a part of his routine after work at the garage that he owns. A local and familiar patron he helps himself to a bottle since he can’t draw a pint of Guinness because the bar’s tap is not working. Brendan (Johnny Hopkins) owner of the pub, house and farm behind it informs him of this sad fact. But no matter. There are plenty of bottles to be had as Jim (John Keating) joins Jack and Brendan for “a small one.” The entertainment for the evening is the entrance of businessman Finbar (Sean Gormley), who will introduce his client Valerie to the “local color,” since she recently purchased Maura Nealon’s old house.

Initially, Jack, Jim and Brendan gossip about the married Finbar’s intentions as he shows up the three bachelors by escorting the young woman to the pub. Jim, caretaker of his mom, and Jack are past their prime in their late 50-60s. Brendan, taken up with his ownership of the pub and farm, is like his friends, lonely and unmarried. None of them are even dating. Thus, the prospect of a young woman coming up from Dublin to their area is worthy of consideration and discussion.

McPherson presents the groundwork, then turns our expectations around and redirects them, after Finbar and Valerie arrive and settle in for drinks. When the conversation turns to folklore, fairy forts and spirits of the area, Valerie’s interest encourages the men to share stories that have spooky underpinnings. Jack begins his monologue about unseen presences knocking on windows and doors, and scaring the residents until the priest blesses the very house that Valerie purchased.

Caught up in his own storytelling which brings a hush over the listeners (and audience), Jack doesn’t realize the import of his story about the Nealon house that Valerie owns. Thankfully, the priest sent the spirits packing. Except there was one last burst of activity when the weir (dam) was being built. Strangely, there were reports of many dead birds on the ground. Then the knocking returned but eventually stopped. Perhaps the fairies showed their displeasure that the weir interfered with their usual bathing place.

Not to be outdone, Finbar shares his ghost story which has the same effect of stirring the emotions of the listeners. Then, it is Jim who tells a shocking, interpretative spiritual sighting. Ironically, Jim’s monologue has a sinister tinge, as he relays what happened when a man appeared and expressed a wish, but couldn’t really have been present because he was dead.

As drinks are purchased after each storyteller’s turn, the belief in the haunting spirits rises, then wanes as doubts take over. After Jim tells his story about the untoward ghost, Valerie goes to the bathroom in Brendan’s house. During her absence Finbar chides all of them. He regrets their stories, especially Jim’s which could have upset Valerie. With Jack’s humorous calling out of Finbar as a hypocrite, they all apologize to each other and drink some more. By this point, the joy of their conversation and good-natured bantering immerses the audience in their community and bond with each other. I could have listened to them talk the rest of the night, thanks to the relaxing, spot-on authenticity of the actors.

Then, once more McPherson shifts the atmosphere and the supernatural becomes more entrenched when Valerie relates her story of an otherworldly presence. Unlike the men’s tales, what she shares is heartfelt, personal, and profound. The others express their sorrow at what happened to her. Importantly, each of the men’s attitudes toward Valerie changes to one of human feeling and concern. Confiding in them to release her grief, they respond with empathy and understanding. Thus, with this human connection, the objectification of the strange young woman accompanied by Finbar at the top of the play vanishes. A new level of feeling has been experienced for the benefit of all present.

After Finbar leaves with Jim, McPherson presents a surprising coup de grâce. Quietly, Jack shares his poignant, personal story of heartbreak, his own haunting by the living. In an intimate emotional release and expression of regret and vulnerability, Jack tells how he loved a woman he would have married, but he let her slip away for no particularly good reason. Mentoring the younger Brendan not to remain alone like he did, Jack says, “There’s not one morning I don’t wake up with her name in the room.”

McPherson’s theme is a giant one. Back in the day when the world was slower, folks sat and talked to each other in community and conviviality. With such an occasion for closeness, they dispelled feelings of isolation and hurt. As they connected, they helped redeem each other, confessing their problems, or swapping mysteries with no certain answers.

As the world modernized, the ebb and flow of the culture changed and became stopped up, controlled by outside forces. Blocked by fewer opportunities to connect, people retreated into themselves. The opportunities to share dried up, redirected by distractions, much as a dam might redirect the ebb and flow of a river and destroy a place where magical fairies once bathed.

McPherson’s terrific, symbolic play in the hands of O’Reilly, the ensemble and creative team is a nod to the “old ways.” It reminds us of the value of gathering around campfires, fireplaces or heating stoves to tell stories. As companions warm themselves, they unfreeze their souls, learn of each other, and break through the deep silences of human suffering to heal.

The Weir runs 1 hour 40 minutes with no intermission at Irish Repertory Theatre (132 West 22nd St). https://irishrep.org/tickets/

‘Irishtown,’ a Rip-Roaring Farce Starring Kate Burton

Irishtown

In the hilarious, briskly paced Irishtown, written by Ciara Elizabeth Smyth, and directed for maximum laughs by Nicola Murphy Dubey, the audience is treated to the antics of the successful Dublin-based theatre company, Irishtown Plasyers, as they prepare for their upcoming Broadway opening. According to director Nicola Murphy Dubey, the play “deals with the commodification of culture, consent and the growing pains that come with change.”

Irishhtown is also a send up of theatre-making and how “political correctness” constrains it, as it satirizes the sexual relationships that occur without restraint, in spite of it. This LOL production twits itself and raises some vital questions about theater processes. Presented as a world premiere at Irish Repertory Theatre, Irishtown runs until May 25, 2025. Because it is that good, and a must-see, it should receive an extension.

The luminous Kate Burton heads up the cast

Tony and Emmy-nominated Kate Burton heads up the cast as Constance. Burton is luminous and funny as the understated diva, who has years of experience and knows the inside gossip about the play’s director, Poppy (the excellent Angela Reed). Apparently, Poppy was banned from the Royal Shakespeare Company for untoward sexual behavior with actors. Burton, who is smashing throughout, has some of the funniest lines which she delivers in a spot-on, authentic, full throttle performance. She is particularly riotous when Constance takes umbrage with Poppy, who in one instance, addresses the cast as “lads,” trying to corral her actors to “be quiet” and return to the business of writing a play.

What? Since when do actors write their own play days before their New York City debut? Since they have no choice but to soldier on and just do it.

The Irishtown Players become upended by roiling undercurrents among the cast, the playwright, and director. Sexual liaisons have formed. Political correctness didn’t stop the nervous, stressed-out playwright Aisling (the versatile Brenda Meaney), from sexually partnering up with beautiful lead actress Síofra (the excellent Saoirse-Monica Jackson). We learn about this intrigue when Síofra guiltily defends her relationship with the playwright, bragging to Constance about her acting chops. As the actor with the most experience about how these “things” work in the industry, Constance ironically assures Síofra that she obviously is a good actress and was selected for that reason alone and not for her willingness to have an affair with Aisling.

Eventually, the truth clarifies and the situation worsens

Eventually, the whole truth clarifies. The rehearsals become prickly as the actors discuss whether Aisling’s play needs rewrites, something which Quin (the fine Kevin Oliver Lynch), encourages, especially after Aisling says the play’s setting is Hertfordshire. As the tensions increase between Quinn and Aisling over the incongruities of how an Irish play can take place in England, Constance stumbles upon another sexual intrigue when no one is supposed to be in the rehearsal room. Constance witnesses Síofra’s “acting chops,” as she lustily makes out with Poppy. This unwanted complication of Síofra cheating on Aisling eventually explodes into an imbroglio. To save face from Síofra’s betrayal and remove herself from the cast’s issues with the play’s questionable “Irishness,” Aisling quits.

Enraged, the playwright tells Síofra to find other living arrangements. Then, she tells the cast and director she is pulling the play from the performance schedule. This is an acute problem because the producers expect the play to go on in two weeks. The company’s hotel accommodation has been arranged, and they are scheduled to leave on their flight to New York City in one week. They’re screwed. Aisling is not receptive to apologies.

What is in a typical Irish play: dead babies? incest? ghosts?

Ingeniously, the actors try to solve the problem of performing no play by writing their own. Meanwhile, Poppy answers phone calls from American producer McCabe (voice over by Roger Clark). Poppy cheerily strings along McCabe, affirming that Aisling’s play rehearsals are going well. Play? With “stream of consciousness” discussions and a white board to write down their ideas, they attempt to create a play to substitute for Aisling’s, a pure, Irish play, based on all the elements found in Irish plays from time immemorial to the present. As a playwright twitting herself about her own play, Smyth’s concept is riotous.

The actors discover writing an Irish play is easier said than done. They are not playwrights. Regardless of how exceptional a playwright may be, it’s impossible to write a winning play in two days. And there’s another conundrum. Typical Irish plays have no happy endings. Unfortunately, the producers like Aisling’s play because it has a happy ending. What to do?

Perfect Irish storylines

In some of the most hilarious dialogue and direction of the play, we enjoy how Constance, Síofra and Quin devise their “perfect Irish storylines,” beginning with initial stock characters and dialogue, adding costumes and props taken from the back room. Their three attempts allude to other plays they’ve done. One hysterical attempt uses the flour scene from Dancing at Lughnasa. Each attempt turns into funny scenes that are near parodies of moments in the plays referenced. However, they fail because in one particular aspect, their plots touch upon the subject of Aisling’s play. This could result in an accusation of plagiarism. But without a play, they will have to renege on the contract they signed, leaving them liable to refund the advance of $250,000.

As their problems augment, the wild-eyed Aisling returns to attempt violence and revenge. During the chaotic upheaval, a mystery becomes exposed that explains the antipathy and rivalry between Quin and Aisling. The revelation is ironic, and surprising with an exceptional twist.

Irishtown is not to be missed

Irishtown is a breath of fresh air with laughs galore. It reveals the other side of theater, and shows how producing original, new work is “darn difficult,” especially when commercial risks must be borne with a grin and a grimace. As director Nicola Murphy Dubey suggests, “Creative processes can be fragile spaces.” With humor the playwright champions this concept throughout her funny, dark, ironic comedy that also is profound.

Kudos to the cracker-jack ensemble work of the actors. Praise goes to the creatives Colm McNally (scenic & lighting design), Orla Long (costume design), Caroline Eng (sound design).

Irishtown runs 90 minutes with no intermission at Irish Repertory Theatre, 132 West 22nd St. It closes May 25, 2025. https://irishrep.org/tickets/

‘Sunset Blvd.’ A Thrilling, Edgy, Mega Spectacle, Starring Nicole Scherzinger

If you have seen A Doll’s House with Jessica Chastain, Cyrano de Bergerac with James McAvoy or Betrayal with Tom Hiddleston, you know that director Jamie Lloyd’s dramatic approach reimagining the classics is to present an unencumbered stage and few or no props. The reason is paramount. He focuses his vision on the actors’ characters, and their steely, maverick interpretation of the playwright’s dialogue. The actors and dialogue are the theatricality of the drama. Why include extraneous distractions? Using this elusively spare almost spiritual approach which is archetypal and happens in what appears to be pure, electrified consciousness, Lloyd is a throwback to ancient Greek theater, which used few if any sets. As such Lloyd’s reimagining of the magnificently performed, uncluttered, cinematically live spectacle, Sunset Blvd., currently at the St. James Theatre in its second Broadway revival, is a marvel to behold.

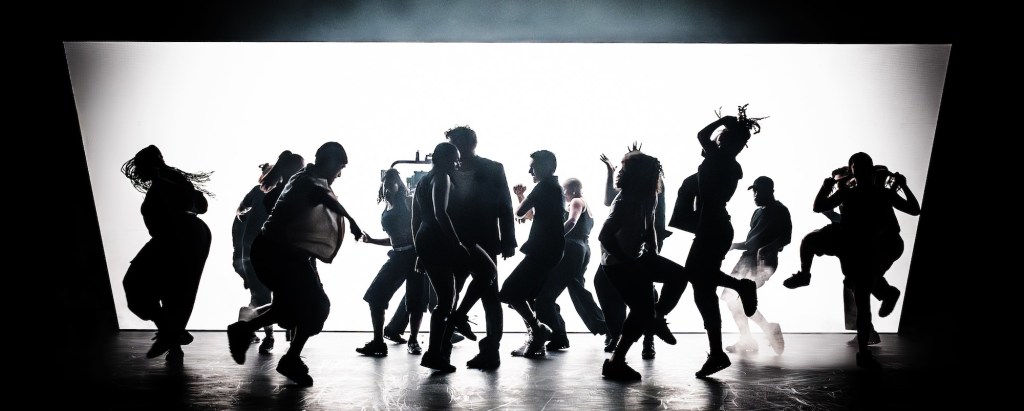

The original production, with music by Andrew Lloyd Webber and book and lyrics by Don Black and Christoper Hampton, opened in 1993. Lloyd’s reimagining configures the musical on a predominately black “box” stage that appears cavernous. Soutra Gilmour’s black costumes (with white accessories, belts, Joe’s T-shirt), are carried through to the black backdrop whose projection, at times, is white light against which the actors/dancers gyrate and dance as shadow figures. The white mists and clouds of fog ethereally appear white in contrast to the background. There is one stark exception of blinding color (no spoiler, sorry), toward the last scene of the musical.

As a result, David Cullen and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s orchestrations under Alan Williams’ music supervision/direction sonorously played by the 19 piece orchestra are a standout. The gorgeous, memorable music is a character in itself, one of the points of Lloyd’s stunning production. From the overture to the heightened conclusion, the music carries tragedy lushly, operatically in a fascinating accompaniment/contrast to Lloyd’s spare, highly stylized rendering. On stage there are just the actors, their figures, voices and looming faces, which shine or spook shadows, sinister in the dim light. The immense faces of the main four characters in black and white, like the silent film stars, gleam or horrify. The surreal, hallucinatory effect even abides when the actors/dancers stand in the spotlights, or the towers of LED lights, or huddle in a dance circle as the cinematographer films close-ups thanks to Nathan Amzi & Joe Ransom.

The symbolism of the staging and selection of colors is open to many interpretations, including a ghostly haunting of the of the Hollywood era, which still impacts us today, persisting with some of the most duplicitous values, memes, behaviors and abuses. These are connected to the billion dollar weight loss industry, the medical (surgery and big pharma) industry, the fashion and cosmetics industry, and more. The noxious values referenced include ageism, appearance fascism (unreal concepts of beauty and fashion for women that promote pain, chemical dependence and prejudice), voracious, self-annihilating ambitions, sexual youth exploitation, sexual predation and much more. Lloyd’s stark and austere iteration of Sunset Blvd. promotes such themes that the dazzling full bore set design, etc., drains of meaning via distraction and misdirection.

The narrative is the same. Down and out studio writer Joe Gillis (the exceptional, winsome, authentic Tom Francis), to avoid goons sent to repossess his car, escapes onto the grounds of a dilapidated mansion on the famed Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. In the driveway, manservant Max (an incredible David Thaxton), mistakes him for someone else and invites him inside. There, Joe meets Norma Desmond (the divine hellion Nicole Scherzinger), a faded icon of the silent screen era in the throes of mania. Norma is “lovingly,” stoked by Max into the delusion that thousands of fans want her to return to her glory days in a new film.

When Norma hears Joe is a screenwriter, like a spider with a fly, she traps him to finish her “come-back” film (she wrote the screenplay). Thus, for champagne, caviar and the thrill of it, he stays, lured by the promise of money, the glamour of old Hollywood and the avoidance of debt collectors. As Norma grows dependent on Joe as her gigolo, he ends up falling for the lovely, unadulterated Betty (the fine, sweet, Grace Hodgett Young). Behind Norma’s back, Joe and Betty collaborate on a script and fall in love. The lies and romance end with the tragic truth.

The seemingly empty stage, tower of lights, spotlights for Norma and live streaming camera closeups projected on the back wall screen, Lloyd is the antithesis of the average director, whose vision focuses on lustrous set design and elaborate costumes and props. In Lloyd’s consciousness-raising universe such gaudy commercialism gaslights away from revealing anything novel or intriguing in the meat of this play’s themes or characterizations, which ultimately excoriate the culture with social commentary.

Soutra Gilmour’s set design and related costumes unmistakenly lay bare the narcissism and twisted values the entertainment industry promotes so that we see the destructive results in the interplay between Max, the indulged Norma and the hapless victim Joe, who tries a scam of his own which fails. Ultimately, all is psychosis, illusions and broken dreams turned into black hallucinations. For a parallel, current example, think of an indulged politician who wears bad make-up that under hot lights makes his face melt like Silly Putty. Again, hallucinations, psychosis, narcissism, egotism that is dangerous and ravenous and never satisfied. Such is the stuff insufferable divas are made of.

In the portrayal of the former Hollywood icon who has faded from the public spotlight and become a recluse, in scene three, when Lloyd presents Gillis meeting Desmond, she is the schizoid goddess and Gorgon radiating her own sunlight via Jack Knowles’ powerful, gleaming spotlights and shimmering lighting design, the only “being” worth looking at against the black background. Throughout, Norma possesses the cavernous space of the stage in surround-view black with white mists jetting out from stage left or right, forming symbolic clouds and fog representing her imagined “divinity” and her confused, fogged-over, abject psychotic hallucinations.

Whenever she “brings forth” from her consciousness “on high,” and empowers her fantasies in song, Lloyd has Knowles bathe her lovingly in a vibrant spotlight. When she emerges from the depths of her bleak mansion of sorrows to sing, “Surrender,” “With One Look,” and later, “As if We Never Said Goodbye,” she brings down the house with a standing ovation. Indeed, Norma Desmond is an immortal. She worships her imagined self at her alter of tribute. Her mammoth consciousness and ethos which Max (Thaxton’s incredible, equally magnificent, hollow-eyed, ghoulish, former husband and current director/keeper of her flaming divinity), perpetuates is key in the tragedy that is her life.

Importantly, Lloyd’s maverick, spare, stripped down approach gives the actors free reign to dig out the core of their characters and materialize their truth. In this musical, the black “empty” stage allows Scherzinger’s Norma to be the primal, raging diva who “will not surrender” to oblivion and death. She is a a god. Like the Gorgon Medusa, she will kill you as soon as look at you. And don’t anyone tell her the truth that she is a “has been.”

Of course, Joe does this out of a kindness that she refuses to accept. Without the black and white design, and cinematic streaming, a nod to the silent screen, which allows us to focus on faces, performances, magnified gestures and looks, the meanings become unremarkable. The theme-those who speak the truth must die/be killed because the deluded psychotic can’t hear truth-gains preeminence and Lloyd’s archetypal production gives witness to its timelessness. In her most unnuanced form, Norma is a dictator who must be obeyed and worshiped. Such narcissistic sociopaths must be pampered with lies.

Thus, in the last scene, Scherzinger’s Norma stands in bloody regalia as the spiritual devourer who has just annihilated reality and punished Joe. She is permissively allowed to do so by Max, who like a director, encourages her to star in her own tragedy, as he destroys her and himself. As Joe narrates in the flashback from beyond the grave, he expiates his soul’s mistakes with his cleansing confession, as he emphasizes a timeless object lesson.

From a theatrical perspective, the dramatic tension and forward momentum lies with Lloyd’s astute, profound shepherding of the actors in an illusory space. This becomes a fluid field which can shift flexibly each night, revealed when Joe, et. al run in circles and criss-cross the stage wildly. Expressionistic haunting, the foggy mists, the surrounding black stage walls, black costumes, the barefoot diva-hungrily filling up the spotlight-the shadowy figures, all suggest floating cultural nightmares. These the brainwashing “entertainment” industry for decades forces upon its fans to consume their waking moments with fear, the fear of aging, fear of failure, fear of destitution, fear of not being loved, fear of being alone. Many of these fears are conveyed in the songs, and dance numbers in Fabian Aloise’s choreography.

And yet, when the protagonist takes control of the black space of the stage around her, we understand how this happens. She is mesmerizing, hypnotic. Seduced by what we perceive is gorgeousness, we don’t see the terror, panic and mania beneath the shining surface. Instead, we are drawn as if she indomitably, courageously stands at the edge of the universe and asserts her being. In all of her growing insanity, we admire her persistence in driving toward her desire to be remembered and worshiped. Though it may not be in the medium she wishes, her provocations and Max’s love and loyalty help her achieve this dream, albeit, an infamous one, by the conclusion, as gory and macabre as Lloyd ironically makes it. Indeed, by the end her hallucination devours her.

Sunset Blvd is a sardonic send up of old Hollywood’s pernicious cruelty and savagery in how it ground up its employees (“Let’s Have Lunch,” Aloise’s brilliant factory town, conveyor belt choreography, referencing the cynical deadening of Joe’s dreams), and how it made its movie star icons into caricatures that bound their souls in cages of time and youth. Also, it is a drop down into tropes of cinema today in its penchant for horror, psychosis and the macabre, represented by Lloyd’s phenomenal creative team which elucidates this in the color scheme, mists, and starkly hyper-drive, electric atmosphere and movement.

Finally, in one of the most engaging, and exuberantly ironic segments filmed live, right before Act II, when Joe sings Sunset Blvd. with wry, humorous majesty, Tom Francis merges the character with himself as a Broadway/entertainment industry actor. During a live-recorded journey unveiling backstage “reality,” Francis/Joe moves downstairs, inside the bowels of the theater and in the actors’ spaces, so we see the actors’ view, from the stairwell to dressing rooms. Then Francis moves out onto 44th Street, joined by the chorus to eventually move back inside the theater and on stage where they finish singing “Sunset Blvd,” in a thematic parallel of Broadway and Hollywood. Broadway with its wicked inclination to sacrifice art for dollars, truth for commercialism with insane ticket prices, is the same if not worse than Hollywood, until now with AI fueling Amazon, Apple, Google, etc.

However, Broadway came first and spawned the movie industry, which poached actors from “the great white way.” Lloyd clearly makes the connection that the self-destructive dangers of the entertainment industry are the same, whether stage, screen, TV or Tik Tok. The competing themes are fascinating and the lightening strike into the “reality of backstage theater,” refreshes with funny split-second vignettes. For example, Francis peeks into Thaxton’s dressing room. Humorously merging with his character Max, Thaxton ogles a photo of the Pussycat Dolls taped to his mirror. Scherzinger was a former member of the global, best-selling music group (The Pussycat Dolls).

As Lloyd’s most expressionistic pared down, superbly technical extravaganza to date, every thrilling moment holds dynamic feeling, sharply illustrated for maximum impact. As an apotheosis of rage when her gigolo lover speaks the truth that dare not be spoken, Scherzinger’s Desmond becomes primal, a banshee, a Gorgon, a Medea who “refuses to surrender” to the idea that Hollywood, a treasured lover, like Jason, abandoned her for new goddesses.

With cosmic rage Scherzinger releases every, living, fiery nerve of vengeance to destroy the who and what that she can never believe. Meanwhile, Max, her evil twin, with clever prestidigitation, in one final act of loyalty to protect her febrile, mad, entangled imagination, has her get ready for the cameras and close-up, despite Joe’s tell-tale gore on her “black slip,” face and hands, which the media can feed off of like flies. No matter, she sucks up all the spotlight hungrily, clueless she will share a solitary room in a padded sell with no one in a prison for the mentally insane. Perhaps.

This revival should not be missed. Sunset Blvd. with one intermission, two hours 35 minutes is at the St. James Theatre until March 22, 2025 https://sunsetblvdbroadway.com/?gad_source=1

‘The Notebook,’ Poignant, Reverent, Knockout Performances by Maryann Plunkett and Dorian Harewood

Fans who have seen the film or read Nicholas Sparks’ titular novel will not be disappointed with The Notebook on Broadway, currently running at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre. With music and lyrics by Ingrid Michaelson and book by Bekah Brunstettter, the musical based on the Sparks’ novel dramatizes the relationship of Noah and Allie using different couples to represent their life stages. With a few changes in the setting from the novel, young and old can appreciate the deeply personal aesthetic and profound expression of fidelity, not often seen, that reveals Allie and Noah’s intimacy and devotion to each other.

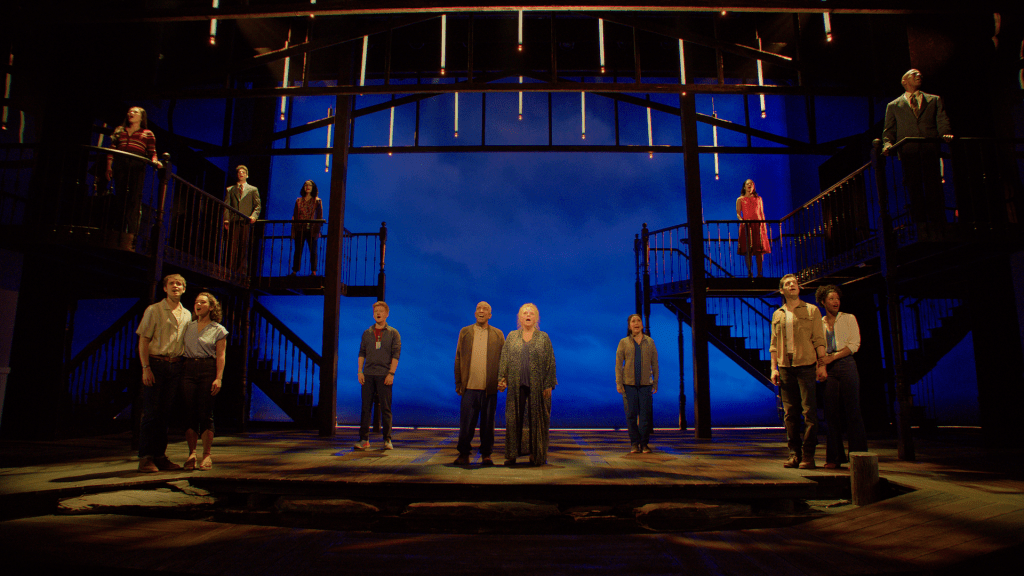

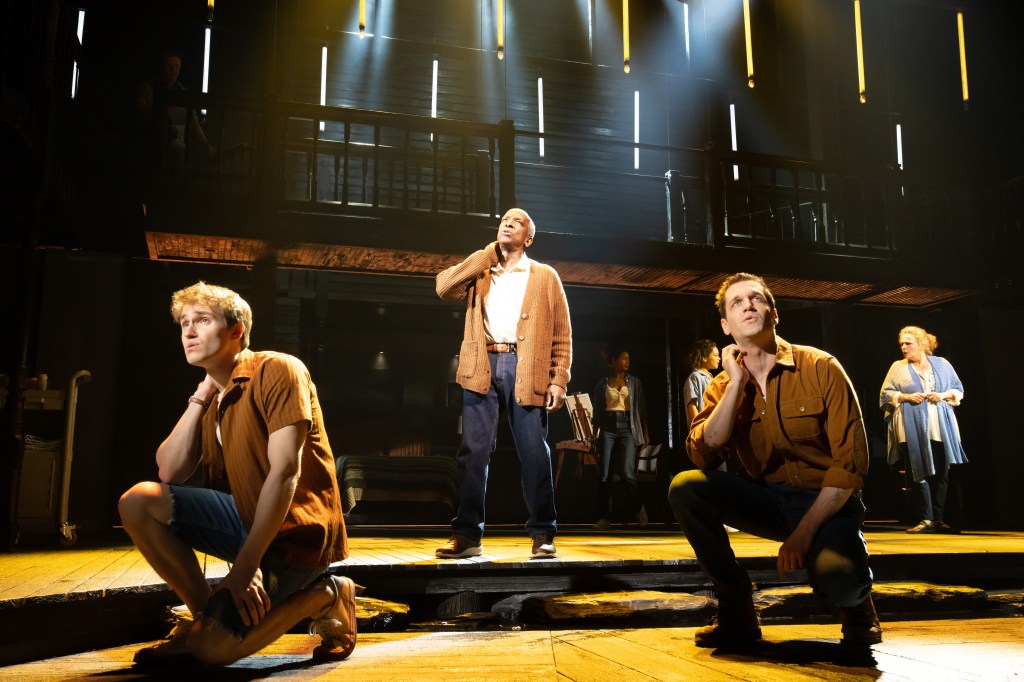

Directed by Michael Greif & Schele Williams, The Notebook’s staging is fluid and stylized, happening mostly in remembrances past. It simultaneously layers the key turning points in the stages of Allie’s and Noah’s relationship (teenage years, late twenties). Through vignettes of scenes between the young Allie (Jordan Tyson) and Noah (John Cardoza) and then the middle Allie (Joy Woods) and Noah (Ryan Vasquez), we understand how the couple’s relationship developed.

We are kept in suspense when Allie’s parents disapprove of Noah and they don’t see each other for years, each pursuing their own dreams. We learn what stood in their way to break them up, and discover how they eventually get back together again, despite their differences in background economically and socially.

The musical takes place in the present in a nursing home where Old Noah (the superb Dorian Harewood), lives to stay near his wife Allie (an incredible Maryann Plunkett), who has degenerative Alzheimer’s. If you have not seen the film or read the novel, you are unaware of Noah’s identity and intentions until he meets with his family and they tell him he cannot afford to stay with their mom in the facility to keep her company. He has to let her go. However, their bond transcends even their children. Noah ignores them.

The strength of the musical is in Greif and Williams’ staging that suggests memory and consciousness brought to life by the journal that Noah reads daily to Allie in her room in the extended care facility. Allie wrote the memoir in remembrance of their love. Noah’s promise to read it to her was made, we learn, when she realized she was becoming immersed in the darkness and confusion of early onset Alzheimer’s. She desperately hoped her own words would trigger her consciousness and memory to maintain their powerful love connection.

The musical’s inherent focus on memory and the indeterminate nature of time in human consciousness reveals how love transcends, heals and can make memories as alive as reality. Eventually, the truth can break through, as it does by the conclusion of the musical, when Allie realizes who Noah is and why he is with her every day. If one has had experiences with relatives who have Alzheimer’s, some relate that in the midst of their relatives’ seeming insentience, there are moments of clarity that appear miraculous. How and why this occurs with this unfortunate condition remains a mystery which one day may be solved.

In respectful consideration of Allie’s situation, Brunstetter’s book encapsulates The Notebook from Noah’s perspective. The directors are mindful of how Noah’s memories and Allie’s words stir Allie, Noah and even Fin (Carson Stewart), who at one point picks up the journal and reads a steamy scene that humorously wows him.

Predominately, the directors strive for coherent, symbolic and meaningful interaction between the couples’ vignettes chronicling, not always in order, but thematically, the events expressing Noah and Allie’s eternal bond created before they were married. As Noah dozes in a chair and dreams of the formation of that bond between Young Noah and Young Allie, the actors are situated downstage to the edge of the proscenium, where there is water and a shoreline bathed in Ben Stanton’s beautiful, bluish tinged moonlight. The night scene conveys an atmosphere of romance. The brief dialogue indicates the couple’s youthful naivete and exuberance where anything is possible even their love. Tyson’s Allie says the words no lover wants to hear; she has to “go home” to her parents.

Ironically, these are words Older Allie in the present says to the nurses and to Old Noah, in confusion, as if she’s searching for the comfort she associates with the home she once made with her life’s partner standing before her, who she doesn’t recognize. Plunkett’s Allie, unsettled in the extended care facility, is triggered by a past that nudges just below her consciousness. She tries but fails to remember the house that Noah built just for her. If only she could get back there, she would know where she is in the present and who the old man is who comes to visit every day.

In that first moonlight and romance scene, Young Noah’s response of eternal love is that Young Allie can stay with him forever, to which she playfully agrees. Simplistic, facile teenagers make promises. However, it is the rare relationship and rare individuals who keep promises in a world of lies, canards, fakery, AI, betrayals, and deceit, where “forever” love is expressed to “get over” and treachery and selfishness are the game plan.

The Notebook is profound in its simplicity, and can be underestimated. Indeed, who is able to love forever, be faithful to one person forever, and not just give lip service to a relationship? This is a key theme of the musical, for through Noah’s unwavering fidelity and Allie’s words, we see how this is possible for this couple who loves simply and endearingly. Overall, the production manifests this theme with sincerity aided by the phenomenal performances of Plunkett and Harewood, who pivot the action forward as the Noahs and Allies affirm the beauty of the relationship in snippets of dialogue and the vitality of song.

Young Noah and Allie lightly reference a forever love which indeed comes true; both age together and Old Noah stays with Old Allie to the very end of their lives. Likewise, the promise they make as kids to see each other the next day also comes true in their lives together, even when a gulf of oblivion separates them. Old Noah sees Old Allie in her room to read from the journal in hope every day. Plunkett’s masterful effort in presenting Allie’s struggle to know her identity and Noah’s, paves the way for the payoff at the conclusion, where she remembers, and together they metaphorically return forever to the home they have made of their love.

The music and songs resonate, some more forcefully, some more lyrically than others. The opening song that Harewood’s Noah sings with the ensemble (except for Older Allie), “Time,” is an inspiring and soulful ballad that embraces life’s mutability and time’s swift passage. The song summarizes the permanence of their future relationship and unfolds with the presence of the younger and middle couples who sing with Old Noah symbolizing Allie and Noah’s younger selves.

It is a soundscape of memories where they identify how they live “to keep going, keep running, keep standing, keep leaning, keep learning, keep hoping.” This premiere ballad establishes what’s to follow, as the ensemble’s voices meld with loveliness in lyrical harmonies. This first song, the song at the end of Act I, “Home,” and the final song, “The Coda” are the most powerfully wrought and most memorable and significant in relating the love and devotion of this unique couple who have been blessed in their love and faithfulness.

Throughout Act I Old Noah persists coaxing Old Allie with the journal passages, and we follow the narrative of their first kiss and first intimacy, first fight, first pledge to write to each other. The musical reveals these two are drawn to love on another level, which is the mysterious unseen of love relationships.

This is in contrast to the socially acceptable diagram of “successful love and marriage,” which Allie’s mother (Andrea Burns), wants for her daughter. Allie’s mother defines happiness by the society’s values of career success and college education, which Allie is forced to accept because of her mother’s betrayal for “Allie’s own good.”

However, Allie and Noah’s relationship, unlike Allie’s mother and father’s relationship, is not defined by material things and upward social mobility. Though Brunsetter doesn’t mention “spiritual” vs. “material,” the undercurrents are clear when the excellent Joy Woods’ Middle Allie in her solo numbers affirms who she is and who she wants to be (“Leave the Light On,” “My Days”). To what extent Noah is a part of who she wants to be, she discovers when she returns to the town and is drawn by curiosity and an unconscious, perhaps spiritual desire to locate the house Noah has built and outfitted for her with his superb carpentry and woodworking skills.

In the subsequent scene the invisible bond between them manifests. We discover what prevented them from being together sooner in a powerful scene between Burns’ mother and Woods’ Middle Allie. Instead of belaboring additional details, Brunstetter moves the action to its foreshadowed conclusion. This doesn’t occur before a few suspenseful, gyrating events in flashback and in the present. One is that Old Noah, who is in the hospital after a stroke, won’t be able to keep his promise to rekindle Allie’s memory ever again.

Kudos to the creative team who carried the directors’ visions for The Notebook. These include David Zinn & Brett J. Banakis (scenic design), Paloma Young’s color coordinated costume costume design, Ben Stanton’s lighting design, Nevin Steinberg’s sound design (I could hear every word) and Mia Neal’s Hair & Wig Design. Additional kudos to Carmel Dean’s music supervision and arrangements and Katie Spelman’s choreography.

The Notebook is a must-see because of the performances and the directors’ vision in bringing reality to a popular work of fiction. Ignore the pandering “tear-jerker” comments by some critics for whom fidelity and eternal love may be empty promises.

The Notebook, one intermission runs until November 24th. Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 West 45th Street between 7th and 8th. https://notebookmusical.com/tickets/

.