Category Archives: Broadway

‘Tammy Faye,’ Starring Olivier-winner Katie Brayben in a Thematically Charged Musical

Tammy Faye

Tammy Faye, with music by Elton John, lyrics by Jake Shears and book by James Graham stars theater heavyweights Katie Brayben, Christian Borle and Michael Cerveris. All of them are letter perfect in the roles of Tammy Faye Bakker, Jim Bakker and Jerry Falwell. Considering that the show is about the rise and fall of the hugely successful PTL Christian network headed up by televangelists Tammy Faye Bakker and Jim Bakker, the production’s chronicle of a complex period in America’s sociopolitical and religious history is ambitious. Currently at the newly renovated Palace Theatre, Tammy Faye runs until December 8th.

For some, the production is hard to swallow. This is unfortunate because its themes are vitally connected to our country. Also, it is a satiric, entertaining new musical whose theatricality coheres in director Rupert Goold’s vision shepherding a fine ensemble and creative technical team. Because I have a familiarity with the Christian evangelical church and, in fact, went to the same church that Jessica Hahn went to during the PTL scandal, and knew and spoke to her, I have a different perspective. Arguably, I may be biased in favor of the musical. That must be considered when reading this review.

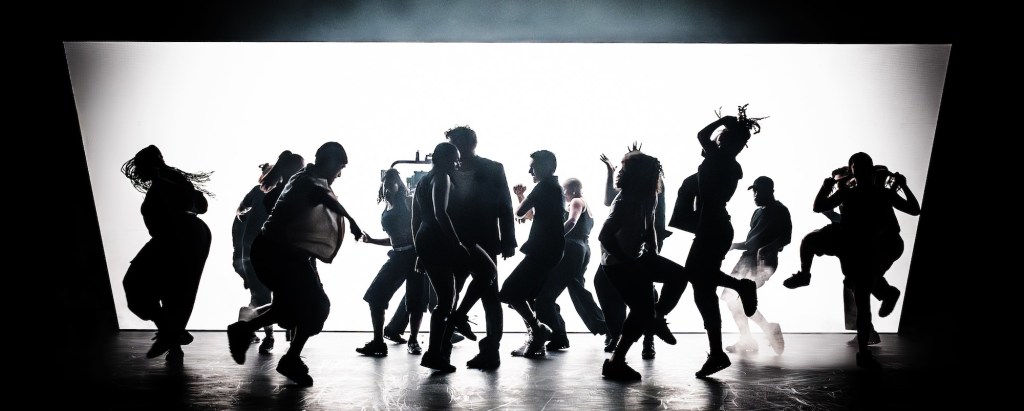

With choreography by Lynne Page and Tom Deering’s music supervision, arrangements and additional music, Tammy Faye presents a fascinating picture of individuals who currently are not held in high esteem. Only one comes out on top as James Graham’s book characterizes her and as the phenomenal voice and acting chops of Katie Brayben performs her. Singing from a core of emotion and heart, illustrating Tammy Faye’s trials of faith, Brayben belts out numbers that overshadow the real Tammy Faye’s voice. These high-points in Tammy Faye’s emotional journey include “Empty Hands,” “In My Prime Time,” and “If You Came to See Me Cry.”

Katie Brayben gives a bravura performance

During these dynamic and compelling songs, Brayben’s Tammy Faye reveals the depth and impact of her betrayal by husband Jim Bakker, as she attempts to find a way forward for and by herself. Not to be underestimated, Tammy Faye is a maverick among the Christian women of the church, a portrayal that we see time and again as she speaks out, despite Christian pastors trying to shut her up. Sharing her opinion at a conference with Billy Graham (Mark Evans), in a beginning flashback of “how it all began,” we note her courage at a time when women took a back seat to any form of leadership. Billy Graham encourages her as the new generation of spiritual warriors in front of a patriarchal, oppressive, conservative group of pastors.

From then on we see her emerge despite being dismissed by the pastors who become the hypocritical villains of Tammy Faye and who sadly lead the way for the massive hypocrisy present in the white supremacist leaning evangelical church today. The Falwell types and white supremacist pastors turn a blind eye to the bullying hatreds and criminality of the MAGA movement they undergird in supporting Donald Trump. Trump’s controversial presidency is in his violating the tenets of Christianity and patriotism. Indeed, he is an alleged pedophile consorting with friend Jeffrey Epstein. He is Putin’s asset who has undermined our election processes twice, and most probably cheated and defrauded the American voter to elicit a “win,” in 2024 (see the Mark Thompson Show on YouTube). He adheres to Putin’s guidance regarding NATO, and on a personal note to emphasize his “godliness,” he’s a lying adulterer and admitted sexual predator (the Hollywood access tape), many times over, in cover ups much worse than Jim Bakker ever committed.

Tammy Faye reveals how we got to the current politics of evangelism

Importantly, for those who would understand how the US “got here” with the rise of evangelism and a brand of political Christianity that belies the true tenets of Jesus Christ’s sermon on the mount, and “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” Tammy Faye gives a crash course in hypocritical Christianity that is right out of St. Paul’s letters to the hypocritical church in Corinthians I and II. It’s interesting to note that over two thousand years later, nothing changes much. Judgment, criticism and condemnation are alive in the human heart and in venues that are supposed to be uplifting the opposite and preaching Christ’s message of love.

Goold stages the production with scenic designer Bunny Christie’s “Hollywood Square” back screen and other projections (video design by Finn Ross), to emphasize the importance of TV to the rise of global evangelism in the 1970s to the present. When the PTL live program is not being taped with dancers and singers, other scenes reflect the importance of satellite TV in the square/screen motif in which appear the various players. Always present as a backdrop are the TV screens reflected in the grid of boxes strikingly lit by Neil Austin that represent what obsesses the actions of the preachers, the Bakkers and their employees (“Satellite of God”). The electric church was televised globally via satellite and its reach was and is expansive, though the screens became smaller on phones after streaming WiFi.

In its symbolism and its wayward themes of church leaders and politicians making damaging and unconstitutional bedfellows, Tammy Faye does its job perfectly, thanks to its creatives. And for that it has received its due misplaced disgust at a time in our nation when Americans have no more patience for hypocrites, scammers and thieves, especially those who profess “Christianity” and lie, cheat, steal, condemn, oppress, restrict, torment and insult as their brand of fun and sanctimony. Hello, Speaker Mike Johnson, Jim Jordan and JD Vance. Nevertheless, Tammy Faye is a vital musical of the time and should be seen for Elton John’s striking music, its irony in how the hypocrites dance around their own lies, and its themes which are more current than ever.

Graham’s book elucidates a version of PTL worthy of note

Book writer James Graham elucidates a version of what happened with PTL that is worthy of note. Laying the blame on the inability of the Christian Church to be united under the first two commandments that Christ preached (love God, love your neighbor as yourself), Graham reveals how Tammy Faye tried to bring disparate groups together with love, but failed. Additionally, to that point, if Tammy Faye had been part of the back room financial arrangements, the fraudulent situation with Heritage Village might not have gotten completely out of hand (“God’s House/Heritage USA”). Indeed, Heritage Village was Jim Bakker’s idea, and clearly, its idea development was mishandled and mismanaged.

Finally, we note that Jim Bakker, whose feckless leadership causes their collapse when he relinquishes PTL and the TV network to Jerry Falwell. With smiling duplicity and treachery, Falwell promises to help the Bakkers get on their feet again and pay their expenses. Tammy Faye warns Jim not to listen to Falwell whom she has always distrusted and deemed a self-serving, condemnatory, hypocritical preacher of hate. Tammy Faye’s unheeded warning proves correct. With his lies, misinformation and mischaracterizations, Falwell upends any goodness the Bakkers accomplish, defames them publicly, and kicks them out of the Christian fellowship for the “good” of the conservative church and himself.

The difference between preachers and preachers

The book underscores the difference between Tammy Faye and Jim, and the other preachers from conservative churches. Falwell (a dynamic Cerveris), Jimmy Swaggart (Ian Lassiter), Pat Robertson (Andy Taylor) and Marvin Gorman (Max Gordon Moore), demean Tammy Faye and Jim Bakker’s way of bringing people to the Gospel. They tolerate them, believing they will fail and are surprised and shocked at their success. Falwell’s massive ego can’t bear to see another preacher in his sphere of influence doing better than he. Not only does Falwell compete for viewership, he goes on their program and insults them attempting to send a message to church goers that they are not of God.

The turning point comes at the prodding of Ted Turner (Andy Taylor), who is concerned about PTL’s finances plummeting because of overspending. Part of the reason Turner suggests the program needs an uplift is because the love and charisma in Tammy and Jim’s relationship has cooled and viewers sense something is wrong. Even friends Paul Crouch (Nick Bailey) and Jan Crouch (Allison Guinn) warn them. At this point in time Tammy has learned of Jim’s infidelity with Jessica Hahn (Alana Pollard), and though he repeatedly asks for forgiveness, Tammy finds it difficult. Increasingly, she relies on prescription pain medicine to anesthetize herself which staff preacher, John Fletcher (Raymond J. Lee), sometimes gives her.

When Tammy strikes out on her own without Jim to carry a show, she draws greater audience viewership which Ted Turner praises. In a heartfelt satellite interview, she speaks with gay pastor Steve Pieters (Charl Brown), about having AIDS. Her public action is courageous. She hugs Steve and accepts him with love into Christ’s fellowship, an anathema to conservative Christianity which condemns gays and believes AIDS is God’s punishment for their sinful homosexuality.

A meeting sealing the fate of PTL

Falwell and the other ministers have a confidential meeting and Falwell even phones President Ronald Reagan (Ian Lassiter), who never acknowledged or worked to stem the AIDS crisis, despite having a gay son and working with gays when he was an actor. Of course, Reagan’s hypocrisy and need for the evangelical church to endorse him is why he speaks to Falwell. In another inflection point, we see the division between church and state morph into an unholy matrimony of religious politicos washing each other’s hands despite the historically traditional separation between church and state.

Thus, Reagan’s public uplifting of the evangelical community via Falwell and others provokes a sea change in the sociopolitical and cultural direction of the nation. The growing intrusion of religion into politics becomes the foundation of constitutional human rights’ reversals seen today, which are particularly uplifted in MAGA states.

Reagan and conservative evangelism, for the voting block-merging church and state

With Reagan in their corner, conservative religious leadership agrees that PTL is moving in an unGodly direction. Falwell and the other preachers see the Bakkers are headed for disaster and they give them a push when the opportunity arises. For example, they get prominent PTL member John Fletcher to turn on Bakker. He sets up Bakker with Hahn, then leaks information when Falwell threatens to expose him of his “infidelities” with gay men if he doesn’t play ball. Falwell also tips off the Charlotte Observer whose reporter Charles Shepard (Mark Evans), investigates the financial arrangements of PTL and finds them to be indebted and insolvent. The situation boils over in “Don’t Let There Be Light.” Tammy, Jim and Jerry recognize their shameful actions and pray that they will not be exposed.

Of course, they are all exposed and vilified by the press and other church leaders. One humorous scene involves Pope John Paul II (Andy Taylor), Mormon leader (Thomas S. Monson), and Archbishop of Canterbury (Ian Lassiter), staged in window squares raised to a higher level above the stage ironically. From their lofty positions, they comment on the troubles of the “electric church” and the Bakkers. Meanwhile, elements of the same unloving hypocrisy are present in their congregations. The pederasty, pedophilia and horrific abuse of the Catholic church is yet to be revealed by the Boston Globe and is still being revealed in the Irish Madeline Laundries and Mother and Baby Homes. Certainly, the church memberships fall off in the Mormon Church and the Church of England. Congregants loathe the leaderships’ hypocrisy.

Acting hate not love

Falwell, Robertson, et. al., end up backbiting each other with hate and jealously. A desperate Bakker, beyond Tammy’s counsel, gives the PTL reigns to Falwell after Tammy learns Jim paid hush money to Jessica Hahn. The scandal widens the more the Bakkers give interviews to defend their positions. In Falwell’s hands, PTL goes bankrupt and is closed down. Tammy divorces Jim and other pastors’ infidelities are exposed as Bakker ends up in jail (“Look How Far We’ve Fallen”). The biased judge ridiculously throws the book at Bakker when murderers are even given lighter sentences.

Eventually, the conservative hypocritical Falwell and Pat Robertson follow in Reagan’s footsteps and run for the presidency. Indeed, their great piety is a sham as they attempt to vault their notoriety to the White House and reap untold rewards, but fail. Unlike Donald Trump who has defrauded his way there again with the treasonous help of various conservative think tanks, True the Vote’s voter challenges in Georgia, voter suppression in swing states, Elon Musk and Putin, Falwell and Robertson’s reputations preceded them and they were rejected as candidates.

Nevertheless, the evangelical Christian movement had an established foothold in politics. The country then wasn’t ready for a conservative, religious president. Now, the MAGAS, building on white supremacists and overturning Reagan’s legacy, have evolved to the point that with Putin’s foreign interference paying influencers to promote misinformation, Trump has become their acceptable, religious MAGA god/autocrat. Despite what Trump/MAGAS/Putin and a complicit press would have voters and the world believe that Trump received “great” voting support, over half the voting public of both parties doesn’t agree with MAGA/Trump’s religious, conservative, oppressive and autocratically unconstitutional mandates. Most probably, if there had been a recount, the results would have revealed otherwise. Better to let sleeping MAGAS, Trump, Putin and others lie.

Favorable reviews in London, bad timing in Manhattan

The show, which originated two years ago at the Almeida Theater in London, received favorable reviews. Opening here at the time it did proved unfortunate because of its subject, a conservative evangelical church, now associated with Donald Trump: a twice impeached, three times indicted, one time convicted criminal, who attempted to overthrow the 2020 election with some of their help via militias and the support of Clarence Thomas’ wife Ginni Thomas.

From Reagan and Falwell and PTL televangelism to the racist, xenophobic, misogynist, MAGA Christianity of today, the conservative brand of evangelicalism has blossomed into “acceptable” white supremacy, oppression, hellfire condemnation and tyranny toward other religions and people of color. Is there any wonder that Tammy Faye, opening around the 2024 election, is a brutal and noisome reminder of what lies, misinformation and money do for those in power, who stir up hate, work unconstitutionally and divide even their own believers from patriotism and the love of God?

Important takeaways

Positive takeaways are the show’s performances which are sterling, especially the leads. The technical team under Goold’s guidance manifests his vision for the production. The book glosses over a complicated series of events (one of which never shows the other side of Jessica Hahn’s professed “virginal innocence,” nor the role her Long Island pastor played in strong-arming the PTL board to pay her hush money).

However, the production does manage to portray one individual, regardless of her psychic flaws, who preached love instead of messages of hate and condemnation (“See you in Heaven”). Tammy Faye did this at a time when standing up for individuals with AIDS was anathema to the general public, let alone Christians. Hers was a courageous, heartfelt stance as an independent Christian church woman. who, alone, went out on a limb to mirror God’s love and show how Christians were supposed to support and help one another.

I heartily recommend this production, especially for those who are interested to understand how evangelism became involved with our politics, despite the supposed separation of church and state. Tammy Faye runs at the Palace Theatre with one intermission until December 8th. https://tammyfayebway.com/?gad_source=1 It’s a shame it is closing so soon.

‘Sunset Blvd.’ A Thrilling, Edgy, Mega Spectacle, Starring Nicole Scherzinger

If you have seen A Doll’s House with Jessica Chastain, Cyrano de Bergerac with James McAvoy or Betrayal with Tom Hiddleston, you know that director Jamie Lloyd’s dramatic approach reimagining the classics is to present an unencumbered stage and few or no props. The reason is paramount. He focuses his vision on the actors’ characters, and their steely, maverick interpretation of the playwright’s dialogue. The actors and dialogue are the theatricality of the drama. Why include extraneous distractions? Using this elusively spare almost spiritual approach which is archetypal and happens in what appears to be pure, electrified consciousness, Lloyd is a throwback to ancient Greek theater, which used few if any sets. As such Lloyd’s reimagining of the magnificently performed, uncluttered, cinematically live spectacle, Sunset Blvd., currently at the St. James Theatre in its second Broadway revival, is a marvel to behold.

The original production, with music by Andrew Lloyd Webber and book and lyrics by Don Black and Christoper Hampton, opened in 1993. Lloyd’s reimagining configures the musical on a predominately black “box” stage that appears cavernous. Soutra Gilmour’s black costumes (with white accessories, belts, Joe’s T-shirt), are carried through to the black backdrop whose projection, at times, is white light against which the actors/dancers gyrate and dance as shadow figures. The white mists and clouds of fog ethereally appear white in contrast to the background. There is one stark exception of blinding color (no spoiler, sorry), toward the last scene of the musical.

As a result, David Cullen and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s orchestrations under Alan Williams’ music supervision/direction sonorously played by the 19 piece orchestra are a standout. The gorgeous, memorable music is a character in itself, one of the points of Lloyd’s stunning production. From the overture to the heightened conclusion, the music carries tragedy lushly, operatically in a fascinating accompaniment/contrast to Lloyd’s spare, highly stylized rendering. On stage there are just the actors, their figures, voices and looming faces, which shine or spook shadows, sinister in the dim light. The immense faces of the main four characters in black and white, like the silent film stars, gleam or horrify. The surreal, hallucinatory effect even abides when the actors/dancers stand in the spotlights, or the towers of LED lights, or huddle in a dance circle as the cinematographer films close-ups thanks to Nathan Amzi & Joe Ransom.

The symbolism of the staging and selection of colors is open to many interpretations, including a ghostly haunting of the of the Hollywood era, which still impacts us today, persisting with some of the most duplicitous values, memes, behaviors and abuses. These are connected to the billion dollar weight loss industry, the medical (surgery and big pharma) industry, the fashion and cosmetics industry, and more. The noxious values referenced include ageism, appearance fascism (unreal concepts of beauty and fashion for women that promote pain, chemical dependence and prejudice), voracious, self-annihilating ambitions, sexual youth exploitation, sexual predation and much more. Lloyd’s stark and austere iteration of Sunset Blvd. promotes such themes that the dazzling full bore set design, etc., drains of meaning via distraction and misdirection.

The narrative is the same. Down and out studio writer Joe Gillis (the exceptional, winsome, authentic Tom Francis), to avoid goons sent to repossess his car, escapes onto the grounds of a dilapidated mansion on the famed Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. In the driveway, manservant Max (an incredible David Thaxton), mistakes him for someone else and invites him inside. There, Joe meets Norma Desmond (the divine hellion Nicole Scherzinger), a faded icon of the silent screen era in the throes of mania. Norma is “lovingly,” stoked by Max into the delusion that thousands of fans want her to return to her glory days in a new film.

When Norma hears Joe is a screenwriter, like a spider with a fly, she traps him to finish her “come-back” film (she wrote the screenplay). Thus, for champagne, caviar and the thrill of it, he stays, lured by the promise of money, the glamour of old Hollywood and the avoidance of debt collectors. As Norma grows dependent on Joe as her gigolo, he ends up falling for the lovely, unadulterated Betty (the fine, sweet, Grace Hodgett Young). Behind Norma’s back, Joe and Betty collaborate on a script and fall in love. The lies and romance end with the tragic truth.

The seemingly empty stage, tower of lights, spotlights for Norma and live streaming camera closeups projected on the back wall screen, Lloyd is the antithesis of the average director, whose vision focuses on lustrous set design and elaborate costumes and props. In Lloyd’s consciousness-raising universe such gaudy commercialism gaslights away from revealing anything novel or intriguing in the meat of this play’s themes or characterizations, which ultimately excoriate the culture with social commentary.

Soutra Gilmour’s set design and related costumes unmistakenly lay bare the narcissism and twisted values the entertainment industry promotes so that we see the destructive results in the interplay between Max, the indulged Norma and the hapless victim Joe, who tries a scam of his own which fails. Ultimately, all is psychosis, illusions and broken dreams turned into black hallucinations. For a parallel, current example, think of an indulged politician who wears bad make-up that under hot lights makes his face melt like Silly Putty. Again, hallucinations, psychosis, narcissism, egotism that is dangerous and ravenous and never satisfied. Such is the stuff insufferable divas are made of.

In the portrayal of the former Hollywood icon who has faded from the public spotlight and become a recluse, in scene three, when Lloyd presents Gillis meeting Desmond, she is the schizoid goddess and Gorgon radiating her own sunlight via Jack Knowles’ powerful, gleaming spotlights and shimmering lighting design, the only “being” worth looking at against the black background. Throughout, Norma possesses the cavernous space of the stage in surround-view black with white mists jetting out from stage left or right, forming symbolic clouds and fog representing her imagined “divinity” and her confused, fogged-over, abject psychotic hallucinations.

Whenever she “brings forth” from her consciousness “on high,” and empowers her fantasies in song, Lloyd has Knowles bathe her lovingly in a vibrant spotlight. When she emerges from the depths of her bleak mansion of sorrows to sing, “Surrender,” “With One Look,” and later, “As if We Never Said Goodbye,” she brings down the house with a standing ovation. Indeed, Norma Desmond is an immortal. She worships her imagined self at her alter of tribute. Her mammoth consciousness and ethos which Max (Thaxton’s incredible, equally magnificent, hollow-eyed, ghoulish, former husband and current director/keeper of her flaming divinity), perpetuates is key in the tragedy that is her life.

Importantly, Lloyd’s maverick, spare, stripped down approach gives the actors free reign to dig out the core of their characters and materialize their truth. In this musical, the black “empty” stage allows Scherzinger’s Norma to be the primal, raging diva who “will not surrender” to oblivion and death. She is a a god. Like the Gorgon Medusa, she will kill you as soon as look at you. And don’t anyone tell her the truth that she is a “has been.”

Of course, Joe does this out of a kindness that she refuses to accept. Without the black and white design, and cinematic streaming, a nod to the silent screen, which allows us to focus on faces, performances, magnified gestures and looks, the meanings become unremarkable. The theme-those who speak the truth must die/be killed because the deluded psychotic can’t hear truth-gains preeminence and Lloyd’s archetypal production gives witness to its timelessness. In her most unnuanced form, Norma is a dictator who must be obeyed and worshiped. Such narcissistic sociopaths must be pampered with lies.

Thus, in the last scene, Scherzinger’s Norma stands in bloody regalia as the spiritual devourer who has just annihilated reality and punished Joe. She is permissively allowed to do so by Max, who like a director, encourages her to star in her own tragedy, as he destroys her and himself. As Joe narrates in the flashback from beyond the grave, he expiates his soul’s mistakes with his cleansing confession, as he emphasizes a timeless object lesson.

From a theatrical perspective, the dramatic tension and forward momentum lies with Lloyd’s astute, profound shepherding of the actors in an illusory space. This becomes a fluid field which can shift flexibly each night, revealed when Joe, et. al run in circles and criss-cross the stage wildly. Expressionistic haunting, the foggy mists, the surrounding black stage walls, black costumes, the barefoot diva-hungrily filling up the spotlight-the shadowy figures, all suggest floating cultural nightmares. These the brainwashing “entertainment” industry for decades forces upon its fans to consume their waking moments with fear, the fear of aging, fear of failure, fear of destitution, fear of not being loved, fear of being alone. Many of these fears are conveyed in the songs, and dance numbers in Fabian Aloise’s choreography.

And yet, when the protagonist takes control of the black space of the stage around her, we understand how this happens. She is mesmerizing, hypnotic. Seduced by what we perceive is gorgeousness, we don’t see the terror, panic and mania beneath the shining surface. Instead, we are drawn as if she indomitably, courageously stands at the edge of the universe and asserts her being. In all of her growing insanity, we admire her persistence in driving toward her desire to be remembered and worshiped. Though it may not be in the medium she wishes, her provocations and Max’s love and loyalty help her achieve this dream, albeit, an infamous one, by the conclusion, as gory and macabre as Lloyd ironically makes it. Indeed, by the end her hallucination devours her.

Sunset Blvd is a sardonic send up of old Hollywood’s pernicious cruelty and savagery in how it ground up its employees (“Let’s Have Lunch,” Aloise’s brilliant factory town, conveyor belt choreography, referencing the cynical deadening of Joe’s dreams), and how it made its movie star icons into caricatures that bound their souls in cages of time and youth. Also, it is a drop down into tropes of cinema today in its penchant for horror, psychosis and the macabre, represented by Lloyd’s phenomenal creative team which elucidates this in the color scheme, mists, and starkly hyper-drive, electric atmosphere and movement.

Finally, in one of the most engaging, and exuberantly ironic segments filmed live, right before Act II, when Joe sings Sunset Blvd. with wry, humorous majesty, Tom Francis merges the character with himself as a Broadway/entertainment industry actor. During a live-recorded journey unveiling backstage “reality,” Francis/Joe moves downstairs, inside the bowels of the theater and in the actors’ spaces, so we see the actors’ view, from the stairwell to dressing rooms. Then Francis moves out onto 44th Street, joined by the chorus to eventually move back inside the theater and on stage where they finish singing “Sunset Blvd,” in a thematic parallel of Broadway and Hollywood. Broadway with its wicked inclination to sacrifice art for dollars, truth for commercialism with insane ticket prices, is the same if not worse than Hollywood, until now with AI fueling Amazon, Apple, Google, etc.

However, Broadway came first and spawned the movie industry, which poached actors from “the great white way.” Lloyd clearly makes the connection that the self-destructive dangers of the entertainment industry are the same, whether stage, screen, TV or Tik Tok. The competing themes are fascinating and the lightening strike into the “reality of backstage theater,” refreshes with funny split-second vignettes. For example, Francis peeks into Thaxton’s dressing room. Humorously merging with his character Max, Thaxton ogles a photo of the Pussycat Dolls taped to his mirror. Scherzinger was a former member of the global, best-selling music group (The Pussycat Dolls).

As Lloyd’s most expressionistic pared down, superbly technical extravaganza to date, every thrilling moment holds dynamic feeling, sharply illustrated for maximum impact. As an apotheosis of rage when her gigolo lover speaks the truth that dare not be spoken, Scherzinger’s Desmond becomes primal, a banshee, a Gorgon, a Medea who “refuses to surrender” to the idea that Hollywood, a treasured lover, like Jason, abandoned her for new goddesses.

With cosmic rage Scherzinger releases every, living, fiery nerve of vengeance to destroy the who and what that she can never believe. Meanwhile, Max, her evil twin, with clever prestidigitation, in one final act of loyalty to protect her febrile, mad, entangled imagination, has her get ready for the cameras and close-up, despite Joe’s tell-tale gore on her “black slip,” face and hands, which the media can feed off of like flies. No matter, she sucks up all the spotlight hungrily, clueless she will share a solitary room in a padded sell with no one in a prison for the mentally insane. Perhaps.

This revival should not be missed. Sunset Blvd. with one intermission, two hours 35 minutes is at the St. James Theatre until March 22, 2025 https://sunsetblvdbroadway.com/?gad_source=1

‘Our Town’ Starring Jim Parsons, Katie Holmes, Richard Thomas in a Superb, Highly Current Revival

Part of the magic of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town is its great simplicity. In Jim Parsons’ (Stage Manager), facile, relaxed, direct addresses to the audience lie the profound themes and templates of our lives. The revival of Our Town directed by Kenny Leon with a glittering cast of renowned film, TV and stage actors, reinforces the currency and vitality of Wilder’s focus on human lives, and the seconds, minutes, hours and days human beings strike fire then are extinguished forever, eventually forgotten as the universe spins away from itself. A play about the cosmic journey of stars and their particle parts in human form in a small representational town on earth, Our Town is iconic. Leon’s iteration of this must see production runs at the Ethel Barrymore Theater until January 19th.

The three act play is in its fifth Broadway revival since the play premiered in the 1930s. This most quintessential of American plays appeared on Broadway when the United States was in the tail end of the Depression during a period of isolationism, and concepts about Eugenics from American researchers had been adopted by the Third Reich to effect their legal platform for genocide. At a curious turning point in American history before a conflict to come, Wilder’s work about life and death in small town Grovers Corners in the fiercely independent state of New Hampshire represented a symbolic microcosm of life everywhere. Perhaps, the play’s themes, especially in the third act were a harbinger, and a warning. In its theme, “we must appreciate life with every breath,” was prescient because WWII was coming to remove millions in a devastation that was incalculable, noted by many as the “deadliest conflict in human history.”

Despite its stark ending and in your face “memento mori,” Wilder’s play found and finds an appreciative audience because of its universality and unabashed assertions about our mortality, walking unconsciousness, and refusal to remain “awake” to the preciousness of our lives.

Indeed, the play has continued to be widely read and performed globally in commercial theater, as well as educational institutions. Leon’s production is no less riveting than other revivals and is even more elucidating and vital in its stylistic dramatic urgency. This is especially so at this point in time, at the eve of a crucial period in our body politic, when we are deciding between two pathways. Do we want to continue to uphold the inexorable verities expressed in Wilder’s themes about living with as much equanimity as possible in a democratic nation that respects the peaceful transfer of power as Grovers Corners symbolizes in Leon’s production? Or do we jettison the rule of law, and the peaceful transfer of power in the US Constitution for a dictatorship in which not all lives are equal or valuable but one life must be bowed down to unequivocally?

Leon’s direction stands in with the former, primarily in the production’s inclusiveness of a diverse group of actors representing Grover’s Corner’s accepting, and non judgmental townsfolk as they go about their business. The business of being human, Wilder divides into three segments (Daily Life, Love and Marriage, Death). Through the omnipotent Stage Manager, which Jim Parsons portrays with a low-key, pleasant avuncular and philosophical style, we quiver at his ironic, pointed rendering of life on this planet.

At the top of the play, the brisk, time-conscious stage manager, after detailing the ancient geological foundation of Grovers Corners, introduces us to the two families which Wilder highlights throughout the play to note their arc of development. Doc Gibbs (Billy Eugene Jones), the local physician, and Mr. Webb (Richard Thomas), the editor of the Sentinel are neighbors. At the turn of the century their wives, like most married women of the time, stay at home, do the housework and prepare meals, none of which is relieved by modern mechanical devices. We learn Mrs. Gibbs (MIchelle Wilson), and Mrs. Webb (Katie Holmes), “vote indirect,” which is to say women are considered incapable of making a rational voting decision.

However, the Stage Manager’s two words hold more weight than he seemingly intends to give them. Instead, he glides by the import of sociopolitical trends because it is unrelated to the cosmic picture alluded to by Rebecca Gibbs (Safiya Kaijya Harris), at the end of Act I. Indeed, the universal themes Wilder drives at do not focus on specific political details. Wisely, Leon takes his cues from the script having Parson’s Manager speak about the titles of the acts as dispassionately and unnuanced as possible. Importantly, Leon “gets” that the functioning of the town, symbolically rendered and opaquely stylized is how Wilder achieves the ultimate impact of the powerful conclusion about appreciating life each day we live it, as insignificant and boring as it may seem at times.

After we meet the children at a breakfast prepared by Mrs. Gibbs and Mrs. Webb via pantomime, the Stage Manager provides the locations of key places like the Post Office, the newspaper office, etc., and reminds us of the town routines, i.e. the train’s arrival and departure, milk and paper deliveries, etc. In the another part of the act, we meet the children who get hooked up in Act II, George Gibbs (Ephraim Sykes), and Emily Webb (Zoey Deutch).

Also, clarified is the town “problem,” Simon Stimpson (Donald Webber, Jr.), who we meet as the play opens when Simon Stimpson conducts the choir in a lovely song. Stimpson becomes the subject of gossip because choir members know he drinks and is drunk a good deal of the time. Mrs. Soames (Julie Halston) gossips about Stimpson and is hushed up by Mrs Gibbs, who tells a little white lie that Stimpson is getting better, then later tells her husband he is getting worse. Webber, Jr. is masterful in the small part. Clues are given about Stimpson’s future, as the character is referred by townspeople in Act I, with some questioning and not knowing “how that’ll end.” Eventually, the Stage Manager shows us how it “ends,” in Act III with Stimpson commenting about life and Mrs. Gibbs responding to him. Whose view should we accept? It, like this production, is open to interpretation.

Three years pass between Act I and Act II, and Parson’s Manager officiates at the marriage between Emily Webb and George Webb, after showing the event which reveals that these two individuals are special and their relationship which is “interesting” is grounded in being truthful to one another. The marriage scene which has been a bit tweaked and slimmed down from the original play, does include the Stage Manager philosophically discussing marriage and particularly George and Emily’s marriage when he says, in part, that he has married over two hundred couples and continues, “Do I believe in it? I don’t know. Once in a thousand times it’s interesting.” Again, we realize the profound comment and question what “interesting,” means.

In the last act which the production speeds to with no intermission as it clocks in at a spare one hour and forty-five minutes, Wilder’s vaguely spiritual metaphors are touching and poignant, despite the production’s bare bones lack of sentimentality. Warning, here is the spoiler, so don’t read the rest of the review if you are unfamiliar with Our Town.

Wilder’s third act resonates with symbols of death, as “the Dead” sit together on chairs as Parson’s unemotional Stage Manager describes the hillside cemetery. Importantly, the lack of Parsons’ emotion stirs the audience deeply. And in Leon’s production, the stylization in the previous acts makes the power of Emily’s return to see and live through her 12th birthday even more potent. Newly dead in childbirth, the Stage Manager gives Emily the privilege, which he says all the dead have, to return to a day in her life to relive it. The morning of her birthday, Emily watches herself, symbolically live without the realization that she will be dead in less than two decades later.

After commenting at how young her parents look and recognizing their love and affection, her pain at her obliviousness to life’s beauty overcomes her and she wants to leave to go back to the cemetery, a lovely spot where her brother Wally, Mrs. Gibbs, Simon Stimpson and Mrs. Soames wait for “something to come out clear.”

Emily’s dialogue is breathtaking and Deutch gets through it with less emotion and passion than is probably required for the audience to feel the reality of her words. “So all that was going on, and we never noticed.” And perhaps more emotion is needed as Emily asks the Stage Manager, “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it? – every, every minute?” The audience in shock silently answers for itself as the Stage Manager responds.

This is the cruel and truthful heart of the play, especially experiencing it through the character of Emily and the Stage Manager’s comforting but remote words which somehow fall ironically when Parsons says, “No. The saints and poets,maybe – they do some.” However, only in death does Emily realize the suffering pain of not appreciating and being grateful for every fabulous, wondrous moment of life.

Certainly, Wilder needs to hit his audience over the head, and they walk out silently receiving the message, then days later forget it. However, for the moments when Leon, Parsons, the cast and the superb and lovely lighting and staging hold us, we “get it.” And we are grateful for teachable moments received through the actors’ fine efforts, the creative team’s craft and Leon’s minimalist stylization. And we appreciate the rich fullness of each gesture, word and grace delivered to make us get in touch with ourselves in our own Grovers Corners’ life.

Kudos to all involved in this magical production. Thornton Wilder’s Our Town runs one hour forty-five minutes without an intermission at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre (243 West 47th Street). https://www.ourtownbroadway.com/?gad_source=1&gclsrc=ds

‘Home,’ The Journey of a Lifetime in Wisdom and Poetry, Review

With lyricism and poignancy in this Roundabout Theatre Company revival of Home, directed by Kenny Leon, Samm-Art Williams spins a story of life’s rhythms, spanning decades during the Great Migration, the time when thousands of Blacks moved with hope to northern cities, leaving Jim Crow’s economic oppression and lynching violence behind. Williams’ covers distances and cultural spaces, all the while evolving his protagonist’s mental, physical and spiritual well being. Home has been receiving a “warm welcome,” at the Todd Haimes Theater, after a prolonged lapse since its original production in 1980 when it was Drama Desk and Tony-award nominated.

Starring Tory Kittles as Cephus Miles, newcomers Brittany Inge and Stori Ayers, portray a multiplicity of characters (40+) from family members to the men and women positively or negatively rubbing up against Cephus on his journey to self-realization. Williams’ representatives move us from a tobacco farm in Cross Roads, North Carolina to a prison in Raleigh, to a northern city (New York), of subways, a roiling, feverish, chaotic place for Cephus that spills out a never-ending cacophony of noise, colors, struggle and conflict.

Then finally, a battered, bruised and reformed drug and alcohol-addicted Cephus has had enough. By that point, he has died to his ego to return home to the rich black soil he thought he had lost, and God’s grace, which was apparently late in coming, but actually was with him all along.

It takes wisdom to know that God has been with him, which he has obviously gained as it is subtly expressed by the ersatz Greek chorus (Inge and Ayers), who introduce the theme of God’s grace which we and Cephus learn abides throughout his life. (“If there was ever a woman or man, who has everlasting grace in the eyes of God. It’s the farmer woman… and man.”) As Inge and Ayers repeat these affirmations as Woman Two and Woman One at the top of play and in a brief song and rhythmic summation of the life of the farmer/sharecroppers who labored and sweat under the sun, then left for the cities, they state that one “fool” came back. And Cephus, “the fool” sits in a rocking chair center stage listening to them.

Cephus, is anything but a fool. His travels have converted him to a contented man of wisdom who has learned, through patience, the hard lesson of God’s everlasting grace. Though we don’t realize it at the top of the play, Cephus has returned from his odyssey. The townspeople’s myths swirl around him (via Inge and Ayers), and town children (Ayers and Inge), whisper the rumors, “Old Cephus Miles. Can’t be saved,” that “he’s dead,” that “he’s a ghost,” as they throw rocks at the windows of the “haunted house,” where he has returned to claim “I’m alive,” “I’m flesh, blood and bone.”

The play is Cephus’ lyrical and dramatic life told in flashback, at times in and out of sequence, like an epic tone poem with the chorus (Ayers and Inge), at the ready to activate his narration, an exegesis exploring and explaining the spiritual text of the grace that threads through his life.

Against a backdrop of tobacco plants, corn stalks, golden lighting by Allen Lee Hughes and a projection of distant acres of crops to the horizon line (the projection changes when Cephus moves to the city), Leon employs a symbolic minimalism of set and props (set design-Arnulfo Maldonado). He adjusts scene changes based on the dialogue and simple objects, a box, a chair, a drop-down cross. Dede Ayite’s costumes and Ayers and Inge’s hair (Nikiya Mathis-hair & wig design), essentially remain the same with a few additions and subtractions (hats, scarves, hair let down-a wig). Miraculously, Leon’s simplicity which fits the thematic, lyrically flowing style of this work, is not only fitting, it is revelatory. However, it is also arcane and opaque at times.

Ultimately, Williams/Leon’s symbolic translation of Cephus’ seemingly “ordinary” existence becomes a spiritual guidepost that focuses on uplifting the souls of those who witness it. Thus, we gradually understand why Cephus quietly dismisses the extraordinarily horrid conditions of racism in the Jim Crow south. Slowly we realize how he withstands injustice related to his poverty and lack of education. That impact is demonstrated when Cephus, unlike those whites who paid to get bone spur deferments or were deferred by college, is drafted during the Viet Nam war. Many Blacks who were unable to get such deferments fought and died in the jungles. He reads the letters of two friends who warn him off going to fight.

But fear didn’t stop Cephus from serving. God’s commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” stops him. A religious conscientious objector, he spends five years in prison because he refuses to kill in battle. After his imprisonment, Cephus gives up sharecropping and heads north. He has tethered his happiness to Pattie Mae, the love of his life, and thinks he may get an education and “improve” himself like she did. Her mother prompted her to go north, get an education, became a teacher and forget about marrying Cephus because she was “better” than he.

However, at this point in his life, destitute and without friends or shelter, somehow Cephus ends up in the city where life befalls him as he waits for God to “come back from Miami” and help him deal with countless issues. Life takes an unbelievable turn for him and he questions God’s absence. With humor Williams relates Cephus’ travails and shares stories out of the traditions of citified Black folk and stories from his country childhood, i.e. his time in the hayloft with Pattie Mae, gambling in the cemetery with friends, loss of close family members and more. Home presents the important and crucial moments in Cephus’ life under the long arm of God, who he prays to, sometimes.

Caught up in the emotionalism of his pain, Cephus, delivered in an incredible performance by Kittles, draws us in and keeps us engaged with humor bytes and memes that reoccur and have their final concluding day. The ending is more than a satisfactory relief and it is the first time we see Cephus grin from ear to ear. Indeed, he has come home in relating and reliving his journey with us with the dogged and wonderful supporting help of Inge and Ayers.

Williams’ style and poetic form is easy listening, as one catches the music inherent in the language and the word beats. At times, however, the pacing and lack of theatricality are uneven and I found myself drifting, despite the tremendous performances of the actors. Overall, the ensemble and their direction by Leon are smashing, as is Williams’ Homeric view which provides a look at war and battle in the human psyche filtered through the American Black experience.

This is one to see. Unless it is extended, the end date is July 21.

Home. Todd Haimes Theatre. 224 West 42nd Street with no intermission. https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/

‘The Great Gatsby,’ Sumptuously Re-imagined, A Must-See, Unforgettable Broadway Spectacle

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald is an iconic American novel set during the Jazz Age. It is about class, the privilege of old wealth and the excesses of the nouveau riche, who can never attain the status of the generational moneyed class, regardless of how hard they try. The Great Gatsby a New Musical, based on the titular novel, retains this key theme of America’s class system from the perspective of unreliable narrator Nick Carraway (Noah J. Ricketts). Carraway memorializes Jay Gatsby, the extraordinaire, whose ability to distill hope and materialize his dreams achieves its own artistic perfection. Examined from the perspective of Nick Carraway (Noah J. Ricketts), the tragic flaw in Gatsby’s process is that he attaches his hope to the imperfection of love and a woman who wasn’t worthy of his vision, faith or love.

The Great Gatsby, a New Musical made its premiere at the Broadway Theatre after its fall run at the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey. With book by Kait Kerrigan in her Broadway debut, music by Jason Howland (Paradise Square), and lyrics by Nathan Tysen (Paradise Square), the musical is suprbly choreographed by Dominique Kelley and acutely directed by Marc Bruni (Beautiful: the Carole King Musical). Overall, it’s a gorgeously conceived production with exceptional ensemble work and flamboyant spectacle that sumptuously re-imagines the distinctive settings, individualistic characters and seminal events that make the novel a singular and timeless classic.

The strength of this production is that Kerrigan, Howland and Tysen are loyal to Nick’s perception of the magnificent Jay Gatsby, portrayed exquisitely by Jeremy Jordan. Jordan’s luscious, exceptional voice, Gatsbyesque persona, and passion do justice to Howland and Tysen’s lyrical and dynamic songs, “For Her,” “Past Is Catching Up to Me,” and the duet “Go.” We empathize with Jordan’s Gatsby, whose near divine love of Daisy (the lovely Eva Noblezada), never fails him, though Daisy can’t handle the irrepressible and divine nature of his efforts to transform time.

In “My Green Light,” an extraordinary duet between Noblezada and Jordan at the end of Act I, the couple consummates their love in Gatsby’s lavish bedroom with the projection of the rippling Long Island Sound at night, and the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock twinkling behind them in the background.

Bruni’s phenomenal staging, Paul Tate DePoo III’s projection and set unifies the key elements of the love relationship between Gatsby and Daisy, the artistry of Gatsby’s vision and his infinite hope (symbolized by the green light), driving it. The acting talents of Jordan and Noblezada, their lustrous singing and the setting are dazzling in this memorable, uplifting scene, where Gatsby, indeed, for a moment conquers time.

At that point we believe that Gatsby’s love is enough to hold Daisy and take her away from the craven, brutish, hypocritical Tom, who breaks his mistress Myrtle’s nose (Sara Chase), and manhandles Daisy leaving bruises on her arms during their quarrels. We believe like Nick and Jordan (the adorable Samantha Pauly), that Tom doesn’t deserve Daisy. However, by the conclusion of the musical, Nick realizes that Tom and Daisy do deserve each other. She won’t even attend Gatsby’s funeral, acting like he never existed. We agree with Nick that Gatsby is “worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

As Nick spins it, the tragedy lies in Daisy’s soulish weakness and her inability to live up to Gatsby’s love to “forget the past,” which he asks her to do in front of Tom in the superbly acted scene at the Plaza Hotel. Together the characters sing the sensational ensemble number “Made to Last.” John Zdrojeski’s Tom is particularly cruel as he arrogantly denounces Gatsby, his criminal bootlegging and his low class background. The lyrics are profound and spot-on. The dynamic music reinforces the themes which the characters forcefully embrace and symbolize. Tom sardonically sings, “It’s not about wealth, it’s blood. It’s class. The day you were born, your die had been cast.” And Gatsby insists, “Daisy, tell him you’re through.” And he tells Tom to “face reality,” affirming that Daisy never loved Tom.

During the explosive turning point in the song, Gatsby insists she renounce her marriage to Tom, and in effect her position and class to which Tom “elevated” her. When Tom sees she falters, that she honestly admits that she loved them both, and that Gatsby “wants too much,” Tom feels secure. He knows she is too weak and insecure to leave him and their daughter. Noblezada’s Daisy, Zdrojeski’s Tom and Jordan’s Gatsby strike the mixture of emotions of their characters with authenticity and power. Daisy’s heightened angst and tenuous state of mind force her to leave the suite, with Gatsby running after her. It is not a position of power from which Gatsby might redeem himself with her, though he tries.

Tom’s defamation and insults to Gatsby’s face and the reality of what Daisy would be giving up to leave him dislocates Daisy to distraction and ultimately causes the fatal accident and final tragedy of the underclasses, who make the mistake of becoming involved with the soulless, unimaginative upper class.

Noblezada portrays Daisy’s confusion with grist, making Jeremy Jordan’s desperation to stop Tom’s brainwashing and win her back even more pronounced. When Tom’s words hit their mark, it’s as if a curtain shuts down Daisy’s mind. Jordan’s Gatsby sees the impact of Tom’s cynicism as it disintegrates all the romance of what he has accomplished in order to turn back time to the fullness of Daisy’s love when Tom never existed. The scene is the brilliant high-point. What follows is the aftermath from which there is no recovering, except that Nick must lead the musical encomium to the greatness of his friend Gatsby. He alone fully grasps who the man was, so of course, he is furious that the papers slam Gatsby and further drive Daisy into oblivion and Tom into victory, as they jaunt away to Hawaii.

Kerrigan, Howland and Tysen are faithful to the key events in the novel down to no one going to Gatsby’s funeral except Nick which Bruni simply stages with black curtains, the casket and bier and red roses. Howland and Tysen fill out Wilson’s mania as he assassinates Gatsby, after Tom sets him up (“God Sees Everything”). As Gatsby sings the reprise “For Her” and Nick imagines how it happens, Wilson joins in and asks God’s forgiveness for using his hands to met out justice and take responsibility for the execution. Of course, Wilson’s ask is ridiculous as his justice is misplaced. Duped by Tom to do violence and pay for it with his own life, Wilson is a pathetic figure. Reflecting on these events, and Daisy and Tom’s nonchalance about Gatsby and the Wilsons, Carraway disdains Daisy and Tom as representative of the careless rich who destroy people and things leaving the Nick Carraways of the world to clean up the mess.

Comedic elements are found in this adaptation which sometime diffuse the impact of the story, as does attention to the secondary characters who are given greater focus. It is also problematic that Nick’s perspective doesn’t cohere throughout the musical, but leaves off in a few scenes, one between Jordan and Daisy.

Some of the comedy is refreshing as in the scene Nick and Jordan share at Nick’s cottage while Daisy and Gatsby meet for the first time in five years. Their relationship is expanded beyond the novel when Jordan and Nick’s intimacy gives way to his proposal of marriage which she is on the verge of accepting, though in Act I she is against marriage. Her characterization is more in keeping with today’s women than women of the early 20th century. Nick’s characterization is largely faithful to the novel. Noah J. Ricketts does a fine job of rendering Nick the unreliable narrator who thinks highly of himself, but doesn’t completely stand up to Tom and Daisy. Instead, he turns tail and runs back to the Midwest away from the” “evil” East, an irony. The only way he can reconcile his self-loathing about his behavior is to attempt to expiate his guilt by memorializing Gatsby.

The Jordan/Nick scenes are humorous and flirtatious. Their number “Better Hold Tight” is a diversion more for its own sake. However, we are not surprised that Nick throws over Jordan who doesn’t show up to Gatsby’s funeral either. She is one of the bad drivers, the careless rich who sicken and disgust him, for they dupes the fools who would seek the dream “boats running against the current” (“Finale: Roaring On”), to only to stumble because their dreams are behind them in the past.

Kerrigan, Howland and Tysen take even greater liberties with the secondary characters for the sake of dramatic purposes. Kerrigan, et. al. strengthen and coalesce the ideas symbolizing George Wilson (Paul Whitty), George’s wife Myrtle (Sara Chase), and Meyer Wolfsheim (Eric Anderson), by giving each of them solo numbers which define their personalities, desires and attitudes. These add to the themes, though they refocus the thrust of Nick’s story of how Gatsby is a romantic hero. The mystery surrounding Gatsby’s identity which is slowly revealed in the novel, is lost in this musical with attention going elsewhere.

As a representative of the criminal class that feeds the dreams of the lower class, breaking the law to do so, thug Wolfsheim joins the company singing “New Money,” which old wealth (Tom), regards as garish and meretricious. Anderson’s Wolfsheim (“who made Gatsby”), also sings and joins the company dancing in the excellent number “Shady.” As Wolfsheim sings, Bruni stages vignettes with each of the character couples being corrupted in their adultery or “sinful” affairs (Jordan and Nick, Gatsby and Daisy, Tom and the Wilsons). According to Wolfsheim, “I’m okay with keeping secrets. I’m okay with being naughty. I approve of indiscretions, if you know how to hide a body.”

Eric Anderson and cast of The Great Gatsby (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

Read the rest of this entry

‘Uncle Vanya,’ Steve Carell in a Superb Update of Timeless Chekhov

A favorite of Anton Chekhov fans is Uncle Vanya because it combines organic comedy and tragedy emerging from mundane, static situations, intricate, suppressed characters and their off-balanced, mired-down relationships. Playwright Heidi Schreck (What the Constitution Means to Me), has modernized Vanya enhancing the elements that make Chekhov’s immutable work relevant for us today. Lila Neugebauer’s direction stages Schreck’s Chekhov update with nuance and singularity to make for a stunning premiere of this classic at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont in a limited run until June 16th.

With a celebrated cast and beautifully shepherded ensemble by the director, we watch as the events unfold and move nowhere, except within the souls of each of the characters who climb mountains of elation, fury, depression and despair by the conclusion of this two act tragicomedy.

Schreck has threaded Chekhov’s genius characterizations with dialogue updates that are streamlined for clarity, yet allow for the ironies and sarcasm to penetrate. At the top of the play Steve Carell’s Vanya is hysterical as he expresses his emotional doldrums at the bottom of a whirlpool of chaos which has arrived in the form of his brother-in-law, Professor Alexander (the pompous, self-important Alfred Molina in a spot-on portrayal), and Alexander’s beautiful, self-absorbed, younger-by-decades wife Elena (Anika Noni Rose). Also present is the vibrant, ironic, self-deprecating, overworked Dr. Astrov (William Jackson Harper), a friend who visits often and owns a neighboring estate.

During the course of the first act, we are witness to the interior feelings and emotions of all the characters who in one way or another are bored, depressed, miserable and disgusted with themselves. Vanya is enraged that he has taken care of Alexander’s lifestyle, even after his sister died in deference to his mother, Maria (Jayne Houdyshell). He is particularly enraged that he believed with is mother that Alexander was a “brilliant” art critic who deserved to be feted, petted and over credited with praise when he lived in the city.

Having clunked past his prime as an old man, Alexander has been fired because no one wants to read his work. He and Elena have run out of money and are forced to stay in the family’s country estate with Vanya and Sonia, Alexander’s daughter (the poignant, heartfelt Alison PIll), away from the limelight which shines on Alexander no more. Seeing Alexander in this new belittlement, though he orders around everyone in the family, who must wait on him hand and foot, Vanya is humiliated with his own self-betrayal. He didn’t realize that Alexander was a blowhard who duped and enslaved him to labor on the farm to supporting his high life, while he pursued his “important” writing. Vanya and Sonia labor diligently to make sure the farm is able to support the family, though it has been a difficult task that recently Vanya has grown to regret. He questions why he wasted his years on a man unworthy of his time and effort, a fraud who knows little about art.

Likewise, Astrov questions his own position as a doctor, admitting to Marina (Mia Katigbak), that he feels responsible for not being able to help a young man killed in an accident. To round out the “les miserables,” Alexander is upset that he is an old man who is growing more decrepit by the minute as he endures believing his young, beautiful wife despises him. Despite his upset, Alexander expects to be waited on by his brother-in-law, mother-in-law and in short, everyone on the estate, which he has come to think is his, by virtue of his wanting it. Though the estate has been bequeathed to his daughter Sonia by Vanya’s sister, his first wife, Alexander and Elena find the quiet life in the country unbearable.

As they take up space and upturn the normal routine of the farm, Elena has been the rarefied creature who has disturbed the molecules of complacency in the lives of Vanya, Sonia and Astrov. Her beauty is shattering. Sonia hates her stepmother, and both Vanya and Astrov fall in love and lust with her. As a result, their former activities bore them; they cannot function with satisfaction, and have fallen distract with want, craving the impossible, Elena’s love. Alexander fears losing her, but realizes if he plays the victim and harps on his own weaknesses of old age, as distasteful as he is, Elena is moral enough to attend to him, though she is bored and loathes him in the process.

The situation is fraught with problems, hatreds, regrets, upsets and soul turmoil, which Schreck has stirred following Chekhov’s dynamic. Thus, Carell’s Vanya and Harper’s Astrov are humorous in their self-loathing as is the arrogant Alexander and vapid Elena who Sonia suggests can end her boredom by helping them on the farm. Of course, work is not something Elena does, which answers why she has married Alexander and both have been the parasites who have sucked the lifeblood of Vanya and Sonia, as they labor for their “betters,” who are actually inferior, ignoble and selfish.

To complicate the situation, Sonia is desperately in love with Astrov, who can only see Elena who is attracted to him. However, Elena is afraid to carry out the possibility of their affair. Instead, she destroys any notion that Sonia has of being with Astrov by ferreting out Astrov’s feelings for Sonia which tumble out as feelings for Elena and a forbidden, hypocritical kiss which Vanya sees and adds to his rage at Elena’s self-righteousness and martyred morality. When Elena tells Sonia that Astrov doesn’t love her, Sonia is heartbroken. It is Pill’s shining moment and everyone who has experienced unrequited love empathizes with her devastation.

When Alexander expresses his plans to sell the estate and take the proceeds to live in the city in a greater comfort and elegance, Carell’s Vanya excoriates Alexander and speaks truth to power. He finally clarifies his disgust for the craven and selfish Alexander, despite Maria’s belief that Alexander is a great man, not the fraud Vanya says he is.

It is a gonzo moment and Carell draws our empathy for Vanya who attempts to expiate his rage, not through understanding how he is responsible for being a dishrag to Alexander, but through manslaughter. The scene is brilliantly staged by Neugebauer and is both humorous and tragic. The denouement happens quickly afterward, as each of the characters turns to their own isolated troubles with no clear resolution of peace or reconciliation with each other.

The ensemble are terrific and the actors are able to tease out the authenticity of their characters so that each is distinct, identifiable and memorable. Naturally, Carell’s Vanya is sympathetic as is Pill’s heartsick Sonia, for they nobly uphold the ethic that work is a kind of redemption in itself, if dreams can never come true. We appreciate Harper’s Astrov in his love of growing forests and his understanding of the extent to which the forests that he plants will bring sustenance to the planet, if even to mitigate only somewhat the society’s encroaching destructiveness. Even Katigbak’s Marina and Sonia’s godfather Waffles (the excellent Jonathan Hadary), are admirable in their ironic stoicism and ability to attempt to lighten the load of the others and not complain.

Finally, as the foils Molina’s Alexander and Noni Rose’s Elena are unredeemable. It is fitting that they leave and perhaps will never return again. The chaos, misery, dislocation and confusion they leave in their wake (including the somewhat adoring fog of Houdyshell’s Maria), are swallowed up by the beautiful countryside and the passion to keep the estate functioning which Sonia and Vanya hope to achieve in peace. Vanya, for now, has thwarted Alexander, by terrorizing Alexander into obeying him in a language (threatening his life), he understands. For this we applaud Vanya.

When Alexander and Elena leave, the disruption has ended and they take their drama and chaos with them. It is as if they were never there. As Vanya and Sonia handle the estate’s paperwork, which they’ve neglected having to answer Alexander’s every need, the verities of truth, honor, nobility and sacrifice are uplifted while they work in silence, and peace is restored to the estate, though they must suffer in not achieving the desires of their lives.

Neugebauer and Schreck have collaborated to create a fine version of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya that will remain in our hearts because of the simplicity and clarity with which this update has been rendered. Thanks go to the creative team. Mimi Lien’s set design functions expansively to suggest the various rooms of the estate, the garden and hovering forest in the background. A decorative sliding divider which separates the house from the forest and allows us to look out onto the forest and woods beyond (a projection), symbolizes the division between the natural and the artificial worlds which influence and symbolize the characters and what they value.

Vanya and the immediate family take their comforts from the earth and nature as does Astrov. Alexander and Elena have forgotten it, finding no solace in the beautiful surroundings and quiet, rural lifestyle which they find boring because they prefer chaos and the frenetic atmosphere of society. Essentially they are soul damaged and need the distractions they’ve become used to when Alexander was famous and the life of the party before he got tiresome and old and disgusting in the eyes of Elena and those who fired him..

The projection of trees that expands entirely across the stage in the first act is a superb representation of what is immutable and must be preserved as Astrov works to preserve. The forest of trees which is the backdrop of the garden, sometimes sway in the wind. The rustling leaves foreshadow the thunder storm which throws rain into the garden/onstage. The storm symbolizes the storm brewing in Uncle Vanya about Alexander, and emotionally manifests when Alexander suggests they sell the estate to fulfill his personal agenda.

During the intermission every puddle and water droplet is sopped up by the tech crew. Kudos to Lap Chi Chu & Elizabeth Harper for their lighting design and Mikhail Fiksel & Beth Lake for their sound design which bring the symbolism and reality of the storm home.

The modern costumes by Kaye Voyce are character defining. Elena’s extremely tight knit, brightly colored, clingy dresses are eye candy for her admirers as she intends them to be to attract their attention, then pretend she doesn’t want it. Of course she is the leisurely swan while Sonia is the ugly duckling in work clothing, Grandmother Maria dresses like the “hippie radical feminist” that she is, and Marina is in a schmatta as the servant who cooks and cleans. Here, it is easy for Elena to shine; there is no competition.

Vanya looks frumpy and uncaring of himself. This reflects his depression and lack of confidence, while Molina’s Alexander is dressed in the heat like a peacock with a scarf, cane and hat and cream-colored suit when we first see him. Astrov is in his doctor’s uniform, utilitarian, purposeful, then changes to more relaxed clothing. The costumes are one more example of the perfection of Neugebauer’s vision and direction of her team.

Uncle Vanya is an incredible play and this update does Chekhov justice. It is a must-see for Schreck’s script clarity, the actors seamless interactions and the creative teamwork which elevates Chekhov’s view of humanity with hope, sorrow and love in his characterizations, especially of Vanya.

Uncle Vanya runs two hours twenty-five minutes including one intermission, Lincoln Center Theater at the Vivian Beaumont. https://www.lct.org/shows/uncle-vanya/whos-who/

‘Mother Play,’ Stellar Performances by Celia Keenan-Bolger, Jessica Lange, Jim Parsons

One of the keys to understanding Mother Play, A Play in Five Evictions by Paula Vogel is in the narration. Currently running in its premiere at 2NDSTAGE, directed by Tina Landau, Vogel’s play has some elements of her own life, but is not naturalistic. It is stylized, quirky, humorous, imaginative and figurative, like most of her plays. In a nod to Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, in the notes, she suggests it is a memory play.

Presumably, the play focuses on a representative mother, Phyllis, portrayed with impeccable sensitivity, raw emotion and nuanced undercurrents of bitterness, humor and irony by the exceptional Jessica Lange. However, the play is actually about a mother-daughter relationship that moves toward reconciliation. As such, the narrator/daughter (the always superb Celia Kennan-Bolger), directs us to her understanding of the last forty years of her life in her relationship with her mother, via the unreliable narrator’s viewpoint.

Should we believe everything the narrator says happened? Or does Martha’s perception of her mother cling to highlights of the events most hurtful and damaging to her? We must ultimately decide or remain uncertain until the play’s conclusion. It’s a delicious conundrum that emphasizes Vogel’s themes of the necessity of developing a deeper understanding of relationships, emotional pain, working through hurt and so much more.

Martha’s genius gains our confidence, empathy and identification with her confessional re-enactment flashbacks as she remembers events. She takes us through the highs and lows of five evictions her family experiences together, after their father dumped them for greener pastures. A key figure in the family dynamic is her two-years older brother Carl, Martha’s brilliant, sweet and kind protector, portrayed with clarity, humor and depth by Jim Parsons.

At the top of the play, which is in the present, Martha is in her early 50s. She tells us that by the time she was 11, their family had moved seven times because their father had a “habit of not paying rent.” Thus, they learned to pack and unpack in a day. She comments with irony that there is a season for packing and a season for unpacking, referencing the Biblical verse (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8), and the Byrd’s song, “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

To destabilize and uproot children from their friends and school mates so many times is a calculation Vogel’s Martha never makes. But it speaks volumes about how the brother and sister rely on each other emotionally, because they are social isolates by necessity because the continued movement which their father, whom we only hear about, didn’t even take into consideration.

As Martha opens a box of the only things her deceased brother had left in their apartment, she takes out a bunny rabbit and a letter Carl had written to her. With the letter, Parson’s Carl materializes and Martha joins him as they step into a series of flashbacks which chronicle events that lead to the five times they were evicted by landlords or they evicted themselves from each other’s lives, only to return, eventually.

Cleverly grounding this family’s living arrangements to present her salient themes about “forever pain,” the impossibility of “mothering,” sacrifice, regret and love, Vogel uses two devices. The first is their furniture which they take with them and rearrange each time they pick up and take off for various reasons. Secondly, there are the roaches, which are magical and symbolic, not only of the poverty and want their father stuck them with, but of the emotional terror and fear of living precariously on the edge of society, sanity and Phyllis’ desire for normalcy.

The roaches, at key moments manifest, swarm, go creepy crawly and loom monstrously in their lives. Since Phyllis signs leases to cheaper basement apartments, promising they will take out the garbage, they are forced to live with these vermin, an indignity of representative squalor from which they never seem to be freed, despite upwardly mobile Phyllis’ attempts to rise to apartments on higher floors.

The first flashback occurs when Martha is twelve, Carl is fourteen, and Phyllis is thirty-seven, in their first apartment away from their father after the divorce. Carl and Martha arrange the furniture and when they are finished, they swivel around Phyllis, reclining in an easy chair in Landau’s deft, humorous introduction of the women the play is allegedly about. Far from “taking it easy,” Lange’s Phyllis demonstrates she is “on edge” and seeks to quell her nerves at this first move without her husband. She immediately importunes her children for the following: her cigarette lighter (a gift from “the only one she loved”), a glass for the gin which she carries in a bottle in her large handbag, and ice, ready made in a tray in a box. After pouring herself a drink and puffing on her cigarette, she begins to relax and says, “Maybe mother will be able to get through this.”

Ironically, the “this” has profound, layered meaning not only for the moment, but for what is ahead for Phyllis, including single parenting, a possible nervous breakdown, poverty, responsibility as a mother, her job and more.

Phyllis pulls out their dinner in a McDonald’s bag from her bottomless black purse, which is empty of money because their father wiped out all the accounts. She speaks of their future-Martha cooking, cleaning and getting dinner, and Carl continuing his excellence of a near perfect score on the PSATs in verbal skills. Phyllis predicts Carl will be the first one in the family to get into college via a scholarship. Martha will take typing and get a job like her mother, so that if a man leaves her like her father discarded her mother, she will be able to support herself.

Though Carl quips flamboyantly about affording rent at the Algonquin, Martha sours at having to share a bedroom with her mother who snores. The favored one, Carl gets his own room. With their new beginning as latch key kids, who have to make their own lunches and deal with their own problems, toward the end of the segment, Carl humorously asks Martha if their childhood has ended.

Being a breadwinner and sole parent is a circumstance Phyllis bitterly resents. Culturally, moms still stayed at home, cooked, cleaned, did the laundry, took care of all the needs of the children, attended to them before and after school, and bowed to their husbands, who had the freedom to do what they pleased, expecting dinner at whatever hour they returned to a wife thrilled to see them. It is this “achievement” that Phyllis wishes for Martha, whom she hopes will marry someone unlike Mr. Herman, in other words a bland man who is unappealing to women and just wants a loyal wife like Martha will be because Phyllis has raised her to be the good woman.

Though Phyllis proudly proclaims this new apartment is a step in the right direction, Phyllis cannot “move on” to annihilate memories of her husband’s past physical and financial abuse, his scurrilous behavior, his machismo insisting all is his way. Filled with regret, Phyllis lapses into negative ruminations about their father who doesn’t provide child support or come to visit. Her cryptic remarks, sarcasm and “treatment” of Martha and Carl, who she openly praises and admires, while being “hard” on Martha, so she won’t marry a fraud, is sometimes humorous, but mostly unjust. In the telling Martha has our sympathy against this cruel, anti-nurturing mother.

Ultimately, we learn that each time they move for a reason that triggers them, each time they pack and unpack and arrange the furniture to settle in, they are still stuck in the same place emotionally because Phyllis can’t forget, forgive or release her anger. And though she adjusts as best she can, she relies emotionally on Carl and Martha, who she eventually evicts when she discovers they live a lifestyle that disgusts her and shatters her dreams for them.

Sprinkled throughout the five evictions and events leading up to them is Vogel’s humor and irony which saves the play from falling into droll repetitiveness because emotionally Phyllis’ needle is stuck in the same groove. Her emotionalism worsens as key revelations spill out about who she is as a woman, who once was adored by the same man who left her for “whores.” Throughout the sometimes humorous, sometimes tragic and upsetting events, Carl and Martha continue to serve and wait on Phyllis until they reach their tipping point. Overcoming these painful events with their mother because they have each other, Carl continues to guide and counsel Martha as a loving brother. This becomes all the more poignant when he leaves the family for various reasons, the last one being the most devastating for Martha and Phyllis.

Landau’s direction and vision for this family whose dysfunction is driven by internal soul damage shared and spread around is acutely realized. The following creatives enhance her vision: David Zinn’s scenic design of movable furniture, Shawn Duan’s projection design of interminable roach swarms, Jen Schriever’s ethereal, atmospheric lighting design (when Carl appears and disappears in Martha’s imagination), and Jill BC Du Boff’s sound design (I heard every word).

Landau’s staging and shepherding of the actors yields tremendous performances. Lange’s is a tour de force, encouraged by Parsons and Keenan-Bloger, whose development through the years pinging the ages from Martha’s 12 years-old and Carl’s 14-years old through to Martha’s fifties is stunning. Parson moderates his maturity and calmness as a contrast to the dire events that occur in the play’s last scenes. The disco scene is amazingly hopeful until Phyllis breaks emotionally and spews fearful, hurtful words.