Category Archives: Broadway

‘Fat Ham’ is Smokin’ Sumptuous in its Broadway Transfer

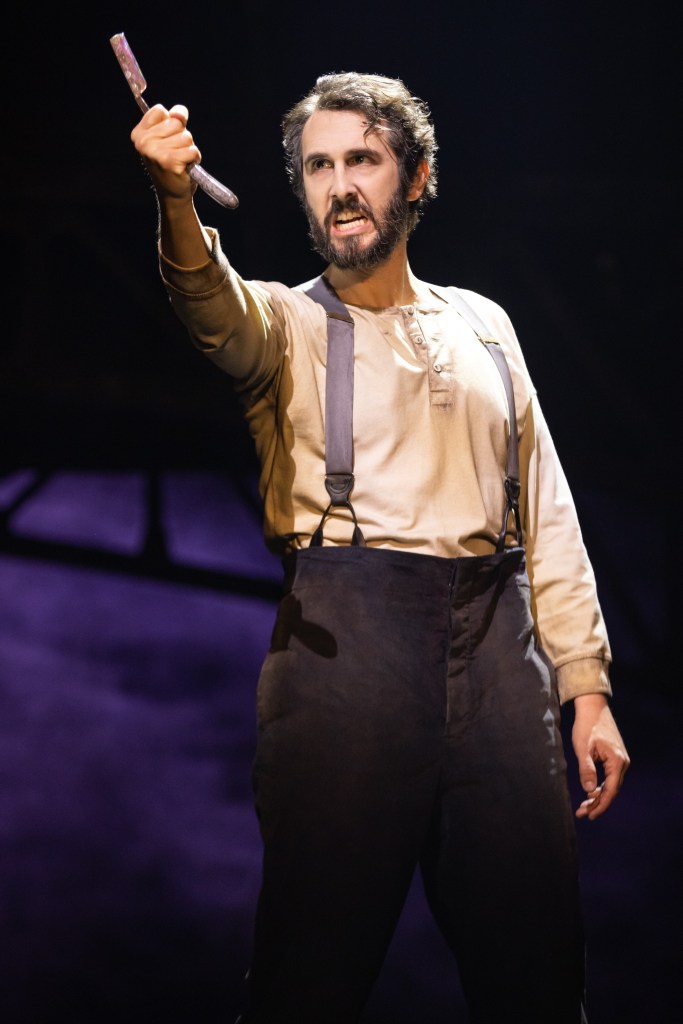

What I enjoy most about seeing Fat Ham in its transfer from The Public Theatre (my review of the Public Theater production) to Broadway’s American Airlines Theatre, are the sardonic tropes which send up William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a Jacobean revenge tragedy, where privileged white royals end up slaughtering each other for power with a particular lack of grace, wisdom and spirituality. Fat Ham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, James Ijames, writes with a joyous, “diabolical” and a steel-sharpened keyboard, with which he extracts the choicest cuts of the Bard’s meatiest speeches, to reveal the enlightened soul of the would-be avenger of his father’s killer, Juicy (the sublime Marcel Spears). Directed by Saheem Ali Fat Ham’s transfer is a delectable winner.

Juicy is the “fat ham,” shortened for Hamlet. The title references Juicy’s necessary acting “chops” in his pursuit of the truth. The title also refers to the succulent pork roast plumping his middle. Ham is also one of the items being served at the barbecue wedding celebration “honoring” mom Tedra (Nikki Crawford) and Juicy’s Uncle Rev (Billy Eugene Jones). Ironically, the meaty feast is a postmortem contribution by the late, great, pit master, Juicy’s father, who owned and managed the family butcher shop and restaurant, which now is owned by Uncle Rev (Claudius-like), who has “supplanted his brother’s place in Tedra’s bed and affections.

Juicy, like the other characters, elements and themes, represents the antithesis of dramatic particulars in Shakespeare’s complex tragedy. Ijames has a blast flipping Hamlet on its head, layering additional profound complexity to a similar plot, as he highlights Black experience in a racist North Carolina. But the beauty of this production is it riotous humor spread “thicc” everywhere you turn, so one can carefully divine the irony, puns, quips and punchy lines that send up the tragedy it twits.

For example white, colonial, Danish heir to a royal dynasty urged to seek revenge by his impeccable, kind and kingly Dad’s ghost? Nope! However, Juicy is a son, disinherited by his murdering uncle and saddled by the wicked, violent ghost of his father to wreck revenge. The method? The ghostly, white-sequined, flashily suited Pap (Billy Eugene Jones plays both brothers), demands that Juicy slaughter Rev, gutting him like they do with the hogs they butcher. After he is slit open, then Pap wants Juicy, who knows butchering, to slice Rev up into roasts, chops, hams and grind his testicles into a powder. Then, Juicy must invite over friends and family to feast on him. Pap’s description is revoltingly humorous, and Juicy questions every word, and rightfully accuses Pap of being unloving, cruel and demeaning to him and his mom.

Antithesis reigns in this brilliant LOL comedy. From Juicy’s race and gender to Pap’s obnoxious, ignoble character, to mom Tedra’s wild, sexy, lap-dancing antics, to porn-loving, hyperbolic cousin Tio, to Larry and Opal’s gay reveal, and relative Rabby’s evangelical praise Jesus, preach-it hypocrisy, Gertrude, Horatio, Laertes, Ophelia and Polonius are partly recognizable. More’s the fun realizing the ironic, deadpan reversals of character to their counterparts.

Tio’s characterization is especially noteworthy. In Hamlet Horatio is the balanced, unemotional, wise, educated courtier, worthy and emblematic of all the traits one would look for in a trusted scholar and friend. Instead, a reserved, watchful Juicy provides the acute, wise commentary to Tio and those his age, while Tio is plainly off the wall and not sure of his identity, as he seek avenues of expression that are unbalanced and addictive. He is seeing a therapist who does give him good advice about how trauma travels through the history of families, as Tio identifies that Juicy’s family has trauma packed into the male genes from slavery onward.

In these roles the actors shine effortlessly. An incredible ensemble, they work seamlessly with not one particulate of comedic pacing or rhythmic, emotional bit out of place. Along with the smooth Marcel Spears, the marvelous players include the crazy wild patriarch and sneaky, underhanded brother Billy Eugene Jones, uber fit, riotous Nikki Crawford as Tedra, the humorously “out-of-hand” Chris Herbie Holland as Tio, the funny, bored, seemingly dim-witted Adrianna Mitchell as Opal, the turn-on-a-dime hysterical Calvin Leon Smith (love his dance) as Larry, and the wonderfully buoyant, hallelujah-loving Benja Kay Thomas as Rabby, Larry’s and Opal’s mom.

Leading this cast, Spear’s Juicy appears content in himself and settled in his identity as a sensitive gay man, in the face of ridicule about his online college education at Phoenix, and his gay sensibility. He eschews his father and uncle for branding themselves with power exemplified by their criminal behavior. He knows the difference between inner strength, fear and inferiority. With equanimity, he receives the information that Tedra prompted by Rev used up his college money for a refurbished bathroom. His non-violent response when Rev and Larry hit him, deemed “soft” by Pap and Rev, is wisdom. Juicy’s inner spirit and soul are cast in the threads of nobility, historically woven by great Black Civil Rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Congressman John Lewis. There is brilliant understatement in the characterizations, if one has the eyes to see Ijames resonant themes.

The beauty of Fat Ham‘s comedic rendering is its lack of preachiness and political rhetoric. With contemplation, sensibility and humor, Juicy, unlike Hamlet, has found his voice and is comfortable in his skin. Thus, he is able to counsel Opal not to be pushed around to fit other’s labels, so she can be herself. Peaceful, calm, he calculates that the blood-thirsty act of revenge is a reprehensible manifestation of generational exploitation and institutional racism. Murder is a curse begun in slavery and perpetrated in Black impoverishment, whose answer has been drug crimes, thefts, Black on Black killings and profitable incarceration by white racist oppressors. The “buck” stops with Juicy’s delicious ham (actor, truth seeker, truth teller).

He is the only one who understands how his family has been incredibly victimized, while Pap and Rev with a modicum of financial security don’t realize how murdering one another is the internalization of racism and weakness born out of a violent past. Juicy affirms after his wonderful delivery of Hamlet’s speech about “catching the conscience of ‘the king'” and noting Rev’s reaction, that revenge is not the suit he wishes to wear. Why should he carry on the family tradition of blood-letting as a generational birthright so he can live down to Pap and Rev’s image of a macho power player? He will set himself free of such chains, and with inner security and knowledge, reject Pap and Rev’s labels and destructive, racially ensnared behaviors.

Nevertheless, as the hysterical events at the barbecue unfold, Juicy turns the “beat” around. In his multiple asides to the “listeners out there in the dark,” Spears creates great humor by winking, gesturing, flipping his hand in coded messages to the audience. This is questioned by the other characters i.e. Tedra who wants to know what he has said about her to us.

The barbecue whose lush set design of a North Carolina one-story middle class home surrounded by trees, sky, a modest deck and backyard, realistically sports set designer Maruti Evans’ astro turf lawn and smoker, where Rev grills the meat. As the large table is laid out and family gathers to eat the biscuits, corn, potato salad and grilled pork, the party takes off into hilarity. Rev delivers a hypocritical prayer with Rabby’s loud, Holy Spirit anointed yells. After they eat, the family and friends tramp around with wild karaoke and charades, during which Juicy catches Rev’s guilty response. However, unlike the tragic end of Hamlet, this is a marvelous comedy and there is no more Black on Black crime. Juicy has ended the family curse of bondage to institution racism’s impact on his family. And Rev does perish. You’ll just have to see Fat Ham to find out how, and to also enjoy the celebratory finish that Calvin Leon Smith’s Larry provides with pizzazz and glam.

Dominique Fawn Hill’s costume design is funny and ironic. Bradley King’s lighting design during the karaoke sequence is atmospheric and mood-filled. Mikaal Sulaiman’s sound design, and Earon Chew Healey’s hair and wig design reflect Saheem Ali’s vision for this superior Broadway transfer which improves upon itself and deepens the Public’s original presentation.

Importantly, the daylight ghost sequence and the illusion designs by Skylar Fox indicate that side by side, the supernatural/spiritual reside with the realities that the characters acknowledge. There is no need to deliver spookiness on a dimly lit stage. The characterization that Ijames draws of Pap’s inner anger, fear and outrage which is karmic (he has killed and he is killed) is frightening enough in all of its humanity. Likewise, how Rev is dispatched by karma is not spooky, it is real and horrifying. This is especially so in a time after COVID when there’s enough fear in unexplained, sudden deaths to last another 100 years. Lastly, the institutional generational historical racism which ghosts in the culture and traditions of this family and binds them to uncontrollable actions they’ve been brainwashed to accept holds enough horror for a lifetime. Juicy’s snapping those chains with his love, peace and irony is a welcome experience for our time.

The production is not to be missed for its superb ensemble, exceptional technical creatives and design teams, and the masterful direction of Saheem Ali, who create his vision to elucidate Ijames’ vital themes. For tickets at the American Airlines Theatre, go to the box office at 42nd street or online at their website: https://www.fathambroadway.com/book-tickets/ But do so now because the show has a limited run and ends in June.

‘Shucked’! “Shucks Ma’am, It’s a Helluva Show!”

If you love corn and even if you hate it, you will laugh at the jokes about or related to the sunny fruit (official classification), in Shucked, the funny, bright, clever, homespun musical fable/farce about love, corn and deeper things. Shucked is a throwback to delightful Broadway productions that are easily relatable and pack a thematic lunch that is palatable and digestible. The cast twits itself throughout and clues the audience in to the one-liners, puns and spicy double entendres, as they judiciously pause for the raucous audience laughter to subside, then deliver the next quip with a twinkle and no wrinkle.

Shucked has something for everyone with innuendos aplenty. Directed by the seasoned Jack O’Brien (Tony Award® winner for Hairspray), who shepherds his cast toward drop-dead pacing and finely honed delivery to produce maximum laughs, the production currently runs at the Nederlander Theatre around two hours and fifteen minutes, including intermission.

With the book by Tony Award® winner Robert Horn (also Drama Desk, Outer Critics Circle, NY Drama Critics’ Circle awards for Tootsie), and music and lyrics by the Grammy® Award-winning songwriting team of Brandy Clark and Shane McAnally, the show is finding its way to hit status, having received its jet-pack from these talented creatives. Featuring an exceptional cast, whose vocals hit the mark every time, Shucked is a musical that leaves one with a smile on one’s face, and songs thrumming through one’s mind. It’s a delectable corn dog that takes you from “farm to fable.”

Introduced by bubbly, enthusiastic Storytellers # 1 and # 2 (Ashley D. Kelley, Grey Henson), who note many funny, lovely facts about and uses of corn (“Corn”), we learn about Cobb County, the place that time forgot because folks had all they needed and walled themselves off from the outside world, using the “high as an elephant’s eye” corn plants. There, Maizy (Caroline Innerbichler) and Beau (Andrew Durand) are standing at the altar ready to receive their wedding vows when the cataclysm happens. Patches of corn plants decorating various sections of the stage begin to die. How Scott Pask (scenic design) manages this and the corn’s restoration is neatly effective.

Believing that Cobb County’s xenophobia is destructive and their worst enemy in face of this corn dying disaster that threatens their way of life, heroine Maizy identifies the county’s chief problem (“Walls”). It has a fixed and irrational paranoia about strangers, and thus, they avoid the outside world. Maizy decides that she must leave the isolation of their existence and find answers to the corn die off. Not only does this upset her cousin Lulu (Alex Newell), and the riotous Peanut (Kevin Cahoon’s deadpan delivery and twanging accent are sincerely hysterical), her fiance Beau (Durand’s macho know-it-all is humorously harmless), puts his annoyed foot down. He tries to exert his will over her when she expresses her desire to leave. However, she has a point when she tells him Cobb County is too limited to provide any answers. Despite Beau’s directives, Maizy leaves, affirming they will be married after she finds the solution to their corn apocalypse.

On her journey from Cobb County, Maizy ends up in Tampa, which the Storytellers conclude is a “humid wonderland of welcoming Tamponians and one douchebag” (“Travelin’ Song”). The number is a clever, humorous build up to the large, bright, neon letters that spell out the city’s name. It is only topped by the city slicker, scam artist Gordy (John Behlmann), a scheming, horse gambling, poseur podiatrist who “removes corns.” Naive Maizy seeks out this scientist and professed expert on corns, not realizing where his “expertise” lies. To make matters worse for Maizy, Gordy is a failed gambler and con (“Bad”). Nevertheless,, the sweet, simple Maizy shows him the rot-ridden ear of corn from home and he promises he might be able to do something.

Sensing an easy way to get out of his $200,000 gambling debt from leg-breaking gangsters, Gordy shows interest in Maizy, after he takes her broken bracelet to jewelers to have it fixed. In a brief, stylized, mini-aside by the all-purpose storytellers, who double this time as disreputable jewelers showing their “range,” (Kelly’s Storyteller #1 quips this), they move the story ahead. They assure Gordy they will buy the unique, valuable stones which can easily be found, “it gathers in clusters like single women in their thirties.” After a seductive dinner and drinks, Gordy produces a perfect ear of corn for Maizy that he tells her he has “fixed.” Of course, she invites him back to Cobb County “to fix” all the corn. Behlmann’s Gordy persists in his romantic seduction to get into Maizy’s rocks underneath the house where she lives.

Thrilled at her own bravery and ability to rectify Cobb County’s corn apocalypse, Innerbichler’s Maizy effectively shows her vocal chops in “Woman of the World.” After the proud, self-satisfied Maizy toots her own horn for bringing back stranger Gordy to meet and save the town, at Beau’s farm Peanut voices his opinion about Beau and Maizy’s love. He quips, “Ever since Maizy came back with this Corn Doctor, you’ve been pissier than a public pool.” In her meet up with Beau to share her “new-found wisdom,” Maizy affirms her sophisticated personality change. In her “pissing-contest” competitiveness with Beau, she lets information slip that devastates Durand’s Beau. He kicks her off his land, then belts out “Somebody Will,” a number that guys can identify with, if they have ever broken up with a long-term partner.

In another women centered number, Lulu (the superb Alex Newell),, belts out a syncopated country tune, “Independently Owned” promoting her whiskey business. As she advertises her autonomy from a man, she warns Gordy to “watch out,” despite her business spiraling downward on an absence of corn supply. Regardless of what happens, Lulu knows who butters her corn. The exchanges among Maizy, Gordy and Lulu, like most of the dialogue in Shucked, are crafted for Henny Youngman/Mae West styled one-liners, with ironic punchlines shot out like rhythmically paced cannon fire. How the actors convey their characters without “pushing it” is authentic and a testament to their comedic brilliance, O’Brien’s direction and Horn’s fine book.

In a winding up toward the end of Act I, Gordy’s situation has a monkey wrench thrown into it. Due to poor cellular connections on two phones, he gets the wrong information which spurs him on in desperation. Over-hearing Gordy’s phone conversations (misinformation), Peanut, Beau and Lulu assess that Gordy is up to no good (“Holy Shit”). How they settle at that conclusion speaks more to their upset that Maizy bravely left and came back with a solution, than hearing the truth. Maizy is forced to defend Gordy’s presence in Cobb County and affirms her faith in him. Alone, she admits she is torn between her feelings for Beau and the possibility of love with Gordy (“Maybe Love”).

Shocked into accepting her belief in him, Gordy persuades the townspeople of his ideas about “fixing” the corn (“Corn”). As the song concludes Act I, Maizy accepts Gordy’s proposal of marriage, and we are left for one intermission to guess whether Gordy’s plan to resurrect the corn has efficacy or his inner shyster is getting over to hightail it outta Cobb with some valuable gem stones.

Horn’s book is tightly spun with the songs which slip in messages of love, acceptance, risk taking, hospitality and compromise, with large portions of savory humor in the lyrics. Jason Howland, who is responsible for music supervision, music direction, orchestrations and arrangements, keeps the score country vibrant, so it sounds like a mix of other music genres in its country beats and rhythms. Japhy Weideman lights the barn for appropriate atmosphere, and John Shivers’ sound design is on target. This is tricky in a show like Shucked, which is dependent on a balance of sound throughout the theater for maximum contagious laughter at the quips, puns and double entendres. Mia Neal’s wig design has a modern flavor with a “Hee-Haw” touch to meld with Tilly Grimes patchwork, homespun costume design of plaids, paisleys and “patches,” that appear to be cut out of various “past-their-prime” clothing items.

Scott Pask’s barn staging has every item and tool one would imagine on a working farm. The intricate, wooden barn structure remains stationary while Lulu’s whiskey still and paraphernalia are brought out when appropriate for some songs in Act II (the hysterical, ironic “We Love Jesus”). And the playing area is large enough to roll out whiskey barrels for the fantastic “Best Man Wins,” as Beau, Peanut, Storyteller #2 and the ensemble jump on the barrels and stand Beau on a long board and move him around. This is an ingenious and visually exciting dance number configured by choreographer Sarah O’Gleby.

There is no spoiler alert. You’ll just have to see Shucked to laugh until your sides ache and pay attention to what happens to bring the corn back from the edge of doom to bless Cobb County with joy, love and a bit of growth toward letting down their walls to accept strangers (“Maybe Love” reprise). Gee! The corn may be a metaphor for something.

This is one you will enjoy in the moment. And afterward, you may try to remember the songs and the wonderful quips, puns and one-liners that had you chortling in the corn row aisles of the audience. For the deeper meanings and references to our time, perhaps you should see it twice. They are cleverly woven into the themes amd strike fire for their currency.

Shucked runs with an end date in September at the Nederlander Theatre (208 West 41st St.). For tickets go to their website: https://shuckedmusical.com/

‘A Doll’s House,’ Jessica Chastain’s Nora is Brilliantly Unbound

As a masterpiece of modern theater Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House presciently foreshadowed the diminution of a women’s role as homemaker. Ibsen shattered the notion of a woman being a husband’s pet, an obedient robot/doll with no autonomy or identity of her own, who cheerfully accepts the delimitation of traditional folkways. A maverick play at the time, A Doll’s House was considered controversial. Ibsen was forced to rewrite the ending for German audiences so it was acceptable.

What would those audiences have said about Amy Herzog and Jamie Lloyd’s stark, minimalist, conceptually powerful, metaphoric version currently at the Hudson Theatre? It is a version which relies on no distracting accoutrements of theatrical spectacle, i.e. period costumes and plush drapery. Nothing physically tangible assists with the unlacing of “the bodice” of Nora’s interior. With “little more” than cerebral irony, and emotional grist, Nora displays her soul in a genius enactment by the inimitable Jessica Chastain, in the production of A Doll’s House, which runs a spare one hour and forty-five minutes with no intermission.

The plot development, characters and themes are Ibsen’s. Nora, a pampered, babied housewife, to save her husband’s life, unwittingly commits fraud by borrowing money from loan shark Krogstad (Okieriete Onaodowan who in the first scene needed to project his voice so as not to appear a weak character which Krogstad is not). Complications arise when Torvald (an exceptional Arian Moayed), receives a bank promotion. With the additional money, Nora plans to quickly pay back Krogstad. But the loan shark threatens to expose Nora’s secret, unless she can save his job at the bank, where her husband has just become his boss.

Tensions increase when Torvald fires Krogstad and hires Nora’s friend Kristine (Jesmille Darbouze). Nora must confront the situation with Torvald before Krogstad exposes her and destroys Torvald’s reputation and their marriage.

Lloyd and Herzog are a fine meld. Herzog strips extraneous words and phrases, though not the substance of the pared-down dialogue. Her version is striking with a natural, informal, un-stilted speech for concentrated listening. There’s even a “fuck you” which Nora proclaims cheerfully to be bold, though not in Torvald’s hearing. The meat is Ibsen; the forks and knives to devour it are sleek and without ornamentation to distract. The themes and characterizations are bone chillingly articulate, which Herzog and Lloyd excavate with every word and phrase in this acute, breathtaking, ethereal, new version of A Doll’s House.

Lloyd eliminates the comforting, elaborate staging where actors might have moved to and fro amongst luxurious furniture and eye-catching, gloriously-hued dramatic sets that show Torvald’s preferred, lifestyle, which Nora scrimps from her own “allowance” to maintain. Instead, the ensemble’s movements are restrained. They step quietly around Soutra Gilmour’s set. Gilmour has distilled Lloyd’s vision to the back stage wall, top-half painted black, with attendant muted white painted on the bottom half of the wall. The flooring is grey. Predominant are the revolving platform and institutional-looking bland chairs which actors bring in and place on the sometime circling platform, or on its outer edges which don’t revolve.

Chastain appears twenty minutes before the production begins, seated in a chair revolving on the platform (I should have counted the repetitions, but I didn’t.). Sitting, she fascinates. Initially, to me, she was invisible; I was distracted, while she quietly walked on bringing her chair. She was a part of the onstage background, muted, unremarkable. That is perhaps one of the many concepts Lloyd and Herzog suggest with this enlightened version that is memorable because it is metaphysical and conceptual, giving rise to themes about soul interiors and women’s invisibility in the patriarchal culture.

One theme this set design suggests is that we travel in our own orbits, going in circles in our own perspectives, unseen and never truly known as psychically present, spiritual beings. And as Ibsen suggests, it takes an inner cataclysm such as Nora experiences to break from traditional mores and behavioral repetitions into a different consciousness and new way of being. This breakthrough, Nora attempts at the conclusion.

Amy Herzog’s modernized language version of A Doll’s House is one for the ages in focusing Ibsen’s power of developing characterizations. It presents an opportunity for Lloyd’s preferred, stylized, avant-garde staging, similar to what he used in Betrayal (2019) and Cyrano (2022). It requires the audience to listen acutely to every word of the dialogue and scrutinize the actors splendid, nuanced emotions which flicker across their faces. This is especially so of Chastain’s Nora, who is chained and bound symbolically throughout, minimally using gestures or any physicality, as she sits in a chair facing the audience. Predominately. she employs her voice and face to convey the interior-organ manifestation of Nora’s tortured, miserable psyche. For example when the wedding ring is returned, Nora and Torvald do not move; there is no ring. They look at one another, however, the unspoken meaning resonates loudly.

Even the tarantella Nora dances at the costume party, Chastain wrenches from herself sitting in the chair in a frantic nearly psychotic frenzy of shaking and kicking. The earthquake physicality that splits Chastain’s Nora apart is the only broad, physical movement, other than walking out of her stifling, meaningless existence, that Chastain and Lloyd effect with novel irony at the conclusion. The chair-dance is an explosive, rage-filled fit of exasperation, principally done for the purpose of distracting Torvald. Desperate to prevent his discovery of corrupt loan shark Krogstad’s blackmail plot, Nora’s diversion succeeds for a time. However, her fear and inner bleeding wounds only augment, until her behavior is exposed and Torvald unleashes his fury, vowing she must not infect the children with her poisonous corruption. Interestingly, the children ethereally “appear” as voices in voice- over recordings. Nora speaks to them, looking out in the direction of the audience. Hypocritically, Torvald demands she stay away from the children, though she must remain with the family to keep up appearances as his jeweled asset and prize doll.

With Lloyd’s symbolic staging, Chastain’s Nora proves that body, soul and mind are inseparably engulfed in the trauma of a paternalistic culture, represented by males who “love her the most” (her father and husband), and psychically straight-jacket and gaslight her to adopt their thoughts, behaviors and attitudes as right and true. To do this she nullifies her existence as a “human being.” In this production, Herzog, Lloyd, Chastain and the ensemble display this truth. It is undeniably representative of women in 1879, the projected number on the back wall of the stage that appears in the beginning of the production.

And when the number disappears, we understand that Soutra Gilmour’s black, white, grey set design, and Gilmour and Enver Chakartash’s costume design (modern dress black), function to speed us through 140 + representative years to display the dominant patriarchal attitudes today. These folkways still straight-jacket, demean and traumatize. If one thinks this is fatuous “woke” hyperbole that is finished, one has only to read the one in four statistics of women who are bound in violent relationships with male partners who beat or abuse them, yet cannot leave for fear of being alone or without the means to support themselves or their children. The LGBTQ community is not excepted from this. Humanity has a penchant for violence. If it is not externalized, the violence is psychic and emotional, where not a hand is raised toward a partner, yet the words and silences traumatize. It is the latter psychic trauma that Ibsen/Lloyd explore.

Whether in Ibsen’s historically, visually laden production of A Doll’s House, or in Lloyd’s naked, bleak and blasted version, it is a despotic spirit that demands obeisance, excluding other ways of being to exalt itself by oppressing and choking the life force from “the other,” whether gender-conforming or LGBTQ. That Chastain has the chops to convince us that we are witnessing every stressed fiber of her nerve endings annihilated, as she inhabits one of the most well-crafted characters in drama, is astounding and not to be underestimated, as some have done, implying her Nora “cries too much.”

Suffice to say, those are not female critics, of which there are far too few. However, her performance is emotionally handicapped accessible for those without a hearing ear, who may need to see Jamie Lloyd’s phenomenally sensitive direction a few times to “get it.” And happily many men do get it. They stood, cheered and whooped during the curtain calls when I looked around to see who was standing at Wednesday’s March 14th matinee. More importantly, women also cheered and whooped.

Clearly, husbands/partners, who might be like Torvald, need to see this production, if they suspect they are like him. Chastain’s Nora is an educational experience in how a particular woman suffers to the breaking point in order to be the prototype ideal wife and mother for a man’s “love” and acceptance. When Nora finally realizes she has the tools to free herself from the false and illusory prison of her own making, she throws off a life and role she believed made her happy to search for definitions of her own happiness.

Moayed’s Torvald, who portrays the solipsistic, presumptuous, self-aggrandizing, martinet with likable charm (how he does this is incredible), exposes her to herself. He smashes her fantasies that he is a white knight, who will do the “beautiful thing,” by sacrificing himself for her, as she has done for him.

Unfortunately, the only one who would sacrifice himself for her is on his way out of life. Chastain’s scenes with Michael Patrick Thornton’s Dr. Rank, who is the couple’s terminally ill close friend, are touching, warm and human, unlike her scenes with Torvald. They should be together, but she won’t push their light flirtations beyond, loyal to her fantasy of Torvald, until she isn’t.

Interactions between Nora and Torvald are increasingly transparent as they devolve into Torvald’s eventual explosion and hatred directed at Nora after discovering the truth. The scenes between Krogstad and Kristine pointedly contrast and move in the opposite direction. Kristine’s persuasive love of Onaodowan’s Krogstad makes him swallow his “pride” and give up his extortion plan. Truth is at the core of their love. Onaodowan and Darbouze are particularly strong and authentic in their scene together which reveals Kristine and Krogstad’s love has remained over the years. On the other hand Torvald and Nora’s toxic relationship functions in falsehoods. Lies are at its core, and what is presumed to be love is convenience and objectification. Torvald demands Nora be his dream doll and she obeys, though it demoralizes her soul.

Kristine’s troubled life has brought her to an understanding of herself in an honesty which Krogstad appreciates, for he wants to give up his corrupt way of life. That Lloyd has selected two Black actors to portray these characters reveals an underlying authenticity and exaltation for their love. Krogstad, who is in the shadows when we first meet him, as he sits behind Nora and blackmails her (unfortunately I had to read the script to understand these lines), appears the villain. He is made more villainous by the society’s ill treatment of him, but his love for Kristine redeems him. Torvald’s inability to love Nora damns them both.

Ironically, when her friend’s love is rekindled, Nora’s love ends, as she realizes Torvald’s true nature and relationship to her. Though he apologizes for “going off” in a diatribe superbly delivered by Moayed, Torvald’s narcissism which can’t abide anything hurting the Torvald “brand,” is egregious. His presumption is a delusion, for she saved his life; he wouldn’t exist but for her.

Herzog’s spare dialogue reveals how loathsome Torvald is in the last scene, when Nora tells him she believed him to be her white knight who would take the blame for her mistake. She insists she would have killed herself to stop his sacrifice for her. It is laughable when he says he would do anything for her, but he “won’t do that.” With conviction speaking for the entire tribe, Moayed states, “No man sacrifices his dignity for the person he loves.” Nora counters, “Hundreds of thousands of women have done that.” When Torvald begs her to stay for the children, he is the weak, despicable coward. His concern is pretentious show to make her feel guilty for leaving. Nora can’t be pressured. She knows Torvald will dump the inconsequential children’s care on their Nanny Anne-Marie (Tasha Lawrence).

Nora allows Torvald’s toxic masculinity to forge the chains which she uses to bind herself in the confines of a paternalistic culture that promotes attitudes about “the little wife.” Meanwhile, his little “bird” lacks a being and ethos apart from him. The only freedom, identity and empowerment Chastain’s Nora will ever receive is one she fashions for herself. This, she ironically and joyously enforces at the play’s conclusion.

How are such incredible performances by Chastain, Moayed and the others so beautifully shepherded? Lloyd economizes to the essence of thought in the lines reworked by Herzog. The evocative minimalism heightens the play’s timelessness and draws into crystal clarity the subtle, “loving” oppressive fantasies men and women (or whatever gender relationships), rely on to sustain power dynamics in their coupling. Without underlying truth and honesty to bolster the relationship and weather horrific storms, the illusions become insupportable and the personalities and relationships shatter.

Kudos to all in the creative team I may not have noted previously, including Jon Clark (lighting design), Ben & Max Ringham (sound design), the ominous, haunting music by Ryuichi Sakamoto & Alva Noto, and dance choreography by Jennifer Rias. For tickets to this maverick production, go to their website https://adollshousebroadway.com/

‘A Beautiful Noise’ Review: The Neil Diamond Musical is a Triumph

How does one take the measure of a man toward the end of his life? Does one examine his relationships with others or does one examine the relationship he has with himself? In The Neil Diamond Musical, A Beautiful Noise, directed by Michael Mayer, currently at the Broadhurst Theatre, book writer Anthony McCarten (The Collaboration, Two Popes) approaches the question using the conceit of a therapeutic doctor/patient relationship.

To McCarten’s credit this complex bio-musical is unlike typical jukebox theater in its positioning of two protagonists: the older Neil of the present with the younger Neil in the past. Driven by this patient/therapist conceit, the musical incorporates Diamond’s songs with flashbacks centered around Diamond’s inspiration for their writing with the added heft of a hero quest. As Diamond unfolds himself to his doctor, certain topics can’t be discussed. He is keeping a part of himself in the shadows. Only through this complex journey into the past will his true identity emerge and be reconciled with his torments. Importantly, we learn through the melding of storytelling and songs why Neil Diamond was inducted in the Songwriters Hall of Fame (1984) and The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (2011). We also learn the sacrifice that it took for him to be who he is.

The doctor/patient motif that provides a thrilling excavation into Diamond’s life and career is cleverly crafted. For weeks a psychologist (Linda Powell) has sessions with a reluctant present-day, older Neil Diamond (the superb Mark Jacoby) who goes to her so that he might examine his inability to interact with his third wife Katie and his children. They have told him that “he’s hard to live with.” Is he? Diamond doesn’t know and on some level, he doesn’t care and prefers to brood (perhaps about his Parkinson’s diagnosis). After a number of sessions (three brief scenes) during which Diamond the elder says little, the psychologist produces his songbook, The Complete Lyrics of Neil Diamond. She does this in the hope of engaging him to discuss songs which he has said reflect his life. In this way maybe a door will be opened into Diamond’s psyche to clear up the issues he is having with his family relationships and most importantly, in his relationship with himself.

Jacoby’s Diamond begins to engage with the psychologist as she reads from the book’s cover that he has 40 of the Top Forty Hits and 129 million of his albums have been sold. When she suggests that they discuss what some of the songs mean to him, he rejects her idea and humorously is piqued that she only is familiar with one of his songs out of his 39 albums. However, when she mentions that title, it strikes a sensitive nerve and he doesn’t want to discuss what it means to him. Unable to leave this “therapy” to please his wife, we understand that he chafes at being controlled, but out of love for Katie and the kids, puts up with the doctor and therapy sessions which have, thus far, proven fruitless.

When the doctor gives him the songbook and suggests that he pick out a song and talk about it, as he rifles through the pages, he notes his proud accomplishments. We hear the “Opening Montage” of a few of his hits. It is as if a genie has been released from his memory as he peruses the book, then shuts it, perhaps because the memories of what was are too painfully overwhelming. But ambivalently, he opens the book again commenting, “what a beautiful noise.” As he remembers, a back up group sings “Beautiful Noise,” and the young Neil Diamond (Will Swenson in an exhilarating performance) appears and sings with them to a backdrop full of glorious light and sound. The song includes an overlapping combination of riffs from some of his classic hits, signature songs which Swenson’s Diamond sings with lustrous power and energy.

The singers who symbolize Diamond’s concept of “The Beautiful Noise” with this song and throughout various numbers are Paige Faure, Kalonjee Gallimore, Alex Hairston, Jess LeProtto, Tatiana Lofton, AAron James McKenzie, Mary Page Nance, Max Sangerman, MiMi Scardulla and Deandre Sevon. They sing backup and dance the journey of Neil’s life and career as the songs explore and reveal his flaws in his relationships, most importantly the one he has with himself. The “Noise” who accompany him are as diverse as the street people who Diamond writes for. It is they and their ancestors who have “Come to America” to seek the American Dream that Neil Diamond himself represents. The play is a revelation of this which we learn at the conclusion of the production, when Jacoby’s Neil discusses the loneliness and fears of his childhood. Only then is he able to reconcile his identities past and present.

After the opening musical reverie, the older Neil then returns to reality in the doctor’s office. These positive remembrances have made Jacoby’s Neil comfortable enough to answer the doctor’s questions about writing his first song in Flatbush, Brooklyn for his high school girlfriend Jaye (Jessie Fisher) who he marries. During this exchange he refers to his escape into music and how he was obsessed with writing and performing songs to “get out of Flabtush.” Ironically, we learn throughout the musical that Flatbush is the place he seems to be forever escaping, before and after he becomes famous. His reasons for running are revealed by the older Neil at the conclusion. McCarten has fashioned the reason as his quest to acknowledge his true worth which will help him achieve peace with himself, Katie and the children

McCarten’s book sets up the paradigm and structure of older Neil digging deeper into his past. As he flashes back and forth in time with younger Neil, who manifests the songs inspired by his life, The Neil Diamond Musical, A Beautiful Noise takes off. Act I showcases Diamond’s rise to fame in the 1960s. Act II follows with his touring and concert glories as his career achieves stunning heights in producing 39 albums, while his personal life after two divorces and an empty bank account are in the abyss. We are delighted to travel back and forth from present to past to present as Jacoby’s Neil frames the journey to Powell’s therapist through flashbacks, as the vibrant, Swenson’s Neil enacts the “dream” and makes it reality.

Guided by the doctor’s questions, Jacoby’s Neil relates his experiences beginning at Aldon Music where he meets Ellie Greenwich (Bri Sudia) in a humorous few scenes, getting his feet wet under her guidance. In one scene he pitches a slower version of “I’m a Believer.” She hears its possibility and voila she sells it to The Monkeys for a hit. Neil’s career is growing as he receives his first gold record. He is a success writing for the Monkeys, but it’s not enough. The older Neil illustrates the part of Neil that is never satisfied. The song is “silly,” he says. However, the doctor points out the depth in the song’s lyrics, a depth which indicates no part of Neil was ever occluded by commercialism. His own poetic voice always showed through in his songs.

Jacoby’s Neil softens with Powell’s therapist. He shares how he moved from writing songs for others to performing them. In a flashback, we note that Ellie believes he is “that good,” when he sings how “Kentucky Woman” should be performed during a “Demo Medley.” Because he needs to develop his performance skills, Sudia’s Ellie has him gain experience at the Bitter End in New York City. After singing a set (“Solitary Man,” Cracklin’ Rose”) Paul Colby (Michael McCormick) gives him $9.00 and asks the shy Neil to return. It is here that young Neil opens up to attractive fellow singer Marcia (Robyn Hurder). He tells her that he enjoys performing live for this, his first time. The uplifting experience strengthens and changes him. It allows him to express a vibrant, alive part of himself he has not acknowledged or thought himself capable of.

We understand how this turning point shapes Diamond into the dynamic performer he eventually becomes with Marcia’s encouragement. Hurder’s Marcia suggests he write more upbeat songs that everyone can identify with. In this flashback segment, she and Neil sing “Song Sung Blue” which intimates how their growing romantic relationship is forged by his need to establish himself in a fruitful career and release his poetic and musical talents to become a success.

McCarten then shifts the flashback to the present in the doctor’s office. Jacoby’s Neil doesn’t want to discuss how his involvement with Marcia while Jaye is pregnant with their second child upends his marriage. Neil fights with the doctor not to remember what is painful that is revealed in songs he wrote at that time. These include songs about being torn between his wife and his mistress. Clearly, he is overwhelmed with guilt having grown close to Marcia who assists him with his career. It is a sore point and he isn’t ready to do the emotional work looking at why he took a self-destructive turn by reviewing how this angst came out in his songs.

So when the doctor settles upon a classic hit created around that time, (which Robyn Hurder dances to in a bright red sexy costume when “Cherry Cherry” is performed) the older Neil jumps at the chance to talk about the creation of his song for “the mob.” These flashback scenes become the humorous high point of Act I. We are intrigued as the older Neil characterizes working with Bang Records as “the biggest mistake of my life.”

Ellie introduces Neil to Bert Berns (Tom Allan Robbins) who runs Bang Records, while Mob Boss Tommy O’Rourke (Michael McCormick) funds the company. In a flashback Swenson’s Neil makes a deal with them to produce hits, if they then produce more artistic songs like “Shilo,” which may not be hits. Though O’Rourke agrees, McCormick’s O’Rourke humorously indicates he has no intention of keeping his promise. In a scene where time stops, the older Neil tries to prevent younger Neil signing on with Bang Records by trying to take the pen away. Older Neil fails and younger Neil signs and is controlled by them. He must produce three hits or end up in peril of his or his family’s lives.

In revealing how younger Neil is torn between Jaye and Marcia, the musical number with the Noise “Cherry Cherry” rocks it as the number physicalizes Neil’s quandary first with Jaye and then moving toward Marcia until he is with her. As Fisher’s Jaye sings “Love on the Rocks,” with Swenson’s Neil begging her to stay, she asks if he loves Marcia. At this point the question is moot.

Neil’s exciting foray into success as he fulfills his contract to mob controlled Bang Records reaches its dramatic high point played out in a dingy Memphis motel, where he retreats to write and get away from the gun happy O’Rourke. Jacoby’s Neil reveals how he was under tremendous pressure to create or suffer the dire consequences. O’Rourke has the Bitter End bombed to send Neil “a message.” Older Neil shares how in Memphis after days of rain, the symbolic sun comes out. He credits the inspiration to “God” coming into the motel room, sealing his children’s future and his own. In thirty minutes the metaphoric dark clouds clear (dark clouds are used as a symbol throughout) and Neil writes one of his signature songs. Act I ends with the rousing “Sweet Caroline.” During their song performance the audience went wild the night I was there. The audience, and Swenson and the Noise “reach out, touching me, touching you.” Theirs is an electric connection that younger Neil is not able to muster with his wife Jaye and their children.

Act II begins with the persona Neil Diamond, who is now famous. Director Mayer has Swenson’s Diamond rise on a platform surrounded by lights and glory with a “Hollywood Squares” type layered set with the band in various “squares.” Clearly, Neil is becoming the award winning legend, singing “Brother Love.” Subsequently, through the older Neil’s retelling, we note that Swenson’s Diamond, with dazzling, sparkling sequins runs from concert to concert, fulfilling the destiny that he dreamed of in Flatbush, Brooklyn, the place that controls his psyche, the place he still runs from. This is especially so even though his concerts sell out with greater fandom than the Rock & Roll King Elvis. In the next decades with Marcia in twenty-five years of marriage, he has it all, friends with the Redfords, a Malibu home and money raining down. Where his first marriage to Jayne dissipated with “love on the rocks,” his marriage to Marcia quietly implodes during phone calls, separate lives and acknowledged disinterest. This is manifest with Hurder’s Marcia and Swenson’s Neil with “You Don’t Send Me Flowers,” in a lovely rendition.

At their divorce, Diamond gives Marcia everything and continues to work. Jacoby’s Neil tells us a few years pass and he meets third time lucky Katie and establishes a family. But the diagnosis has brought him to a place of reckoning at the therapist’s office. And we are back in the present when Powell’s therapist asks the question about Neil’s feelings of being alone, an emotion which permeates many of his songs. During this segment Mark Jacoby’s quiet resolve and recalcitrance breaks open in expansive revelation.

For the first time we hear him sing filled with the depth of years of repression to claim his self-affirmation in “I Am I Said.” Jacoby hits it out of the ball park and brings the entire journey into completion as Swenson’s Neil joins him and the two identities are conjoined. It is an astounding, brilliant piece of writing coupling the elements and characters bringing them into sharp focus. The power of the moment hinges on Jacoby’s portrayal of Neil which is heartfelt, touching and human. The conclusion memorably coalesces the dream coming to its full humanity in Neil Diamond. Merging his identity as a performer and as a cultural prophet he gains a new understanding of his emotions from the past viewing them with the comfort in the present reality of who he is and what he has accomplished.

Directed by Michael Mayer with Steven Hoggett’s choreography and Sonny Paladino’s music supervision and arrangements and the near-perfect performances, this astounding and prodigious effort is bar none. Above all it is a tribute to Neil Diamond the performer and Neil Diamond, the man, like all of us, broken by his own inner fears and isolation which is an integral part of his creative spirit and artistic genius. The breadth of the songs included in the show which reveal that Diamond mastered pop, rock, country and blues indicates why in addition to his awards is also an honoree at the Kennedy Center Honors and a recipient of the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (2018).

Importantly, The Neil Diamond Musical, A Beautiful Noise probes themes that reveal how driving ambition and talent shadow an artist’s personal life. In chasing the dream it is sometimes difficult to fully enjoy one’s success. In his resolution at the conclusion, Jacoby’s Neil understands the importance of this and expresses gratefulness at all the directions, all the roads his life has gone down.

There are a few critical junctures that don’t quite work and sometimes the staging and sound were problematic for those not seated direct center. But these details are overshadowed by the ingenuity of the book, the resonance and gorgeousness of Diamond’s music, the energetic, believable performances and the organic, modern and retro dances. Jacoby’s Neil who is listening and participating as he watches Neil’s own reflections manifest before him, never flags in his portrayal in a difficult, complex role. Neither does Swenson who’s evocation of Diamond is an intimation of his attitude and spirit and not an imitation. Hurder, Powell, Fisher and Sudia are excellent and Sudia is flexible doing double time as younger Neil’s mom. Robbins and McCormick fulfill their portrayals with humor and kudos to them for taking on additional roles.

David Rockwell’s scenic design, Emilio Sosa’s costume design, Kevin Adams’ fine lighting design and Jessica Paz’s sound design work to deliver an amazing production. Noted are Luc Verschueren’s hair, wig & makeup design and Annmarie Milazzo’s vocal design. Bob Gaudio, Sonny Paladino & Brian Usifer delivered the superb orchestrations and Brian Usifer is responsible for incidental music and dance music arrangements.

If Neil Diamond’s music doesn’t rock for you, see it for the performances and spectacle. If you adore Neil Diamond, what are you waiting for? Go to their website for tickets and times https://abeautifulnoisethemusical.com/

.

t

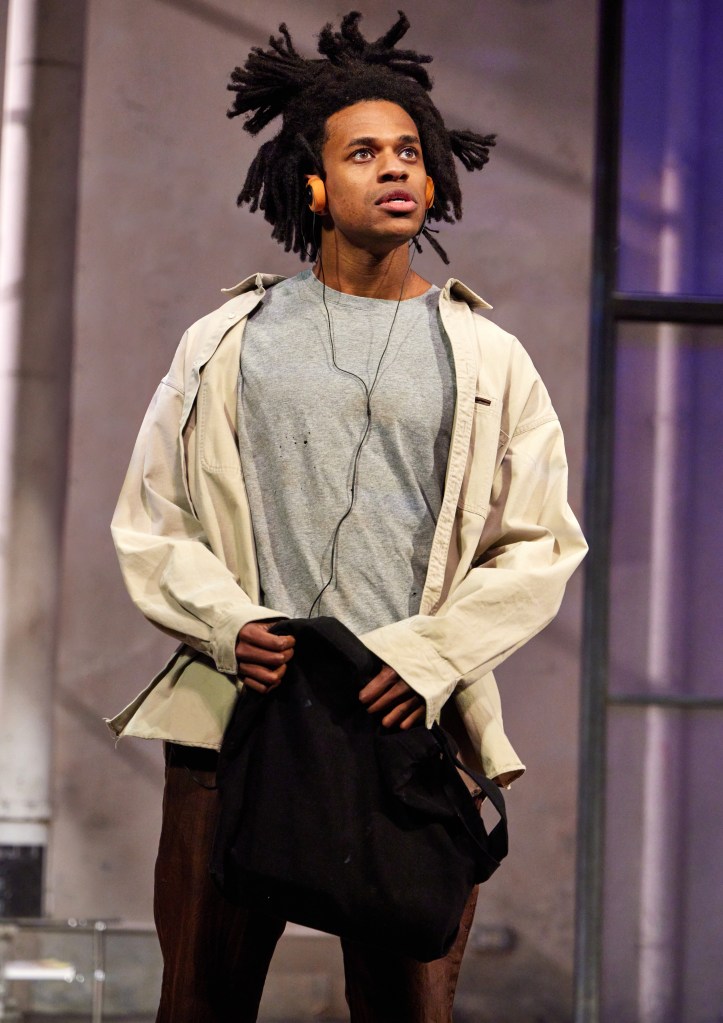

‘The Collaboration,’ Paul Bettany and Jeremy Pope are Brilliant as Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat

Whether you are an art aficionado, fan or critic, The Collaboration, by Anthony McCarten about Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s joint effort to produce paintings together is an astonishing, dynamic production. Starring Paul Bettany (an Inspector Calls-West End) and Jeremy Pope (Choir Boy) and directed by Kwame Kwei-Armah, the two-act play currently runs at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, extended until 5 February. This production which hails from the Young Vic Theatre is not to be missed.

Warhol’s and Basquiat’s alliance was an unusual meld for both artists, who were at different points in their careers and who, according to McCarten in the first act, were a thesis/antithesis in their personal lives, perspectives and personalities. Because Warhol and Basquiat are icons who helped transform the art world as unique and indelible fixtures in their own right, The Collaboration is of seminal importance. Not only does the work identify aspects of the artists’ individual and collective graces, it also inspires further exploration into the lives of these individuals and their synergistic and productive relationship.

Bettany and Pope’s prodigious acting skills and Kwame Kwei-Armah’s superb direction in helping them tease out memorable details of emotion, gesture and nuance allow the actors to live and breathe their characters onstage. Bettany and Pope are a pleasure to watch in their authenticity as their portrayals by the second act lift toward the heavens into the phenomenal. They inhabit Warhol and Basquiat with vulnerability and humanity. So comfortably do they don the artists’ ethos, one forgets the play is a stylization and evocation of two mythic figures who attained immortality in spite of themselves.

Indeed, the production takes us on a fantastic journey with intermittent elements of realism that all the more enhance the beauty and tragedy of these men, whose lives were cut short. Though Andy Warhol lived to be 58 years-old, Jean-Michel died of an overdose of heroin at twenty-seven. At the conclusion McCarten suggests that their individual and collective work and their ability to inspire and whimsically play off one another are an irrevocable, immutable and timeless gift to all of us.

The award-winning playwright (known for films The Theory of Everything {2014) Two Popes {2020} and the book writer of A Beautiful Noise) grapples with revealing their combined efforts in the short period of time they worked together. Indeed, the cultural mystique and reputation that precedes these men sometimes gets in the way. The more one knows about Warhol and Basquiat, the more frustrated one may become with McCarten’s presentation of their relationship, whose closeness is developed in filmed events of Bettany and Pope doing activities together, projected on the backstage wall and side walls during the intermission between Act I and Act II. Thus, if one leaves to get a drink or take a trip to the bathroom, the vital aspects of how Warhol and Basquiat’s relationship develops and how the men bond over time will be missed.

McCarten first introduces us to Warhol who visits the gallery of Bruno Bischofberger (Erik Jensen’s accent at times trips over itself). There, Andy inspects Basquiat’s paintings as Bruno attempts to sell him on his idea of a collaboration. Though Bruno makes it seem that Basquiat is “dying” to work with Warhol, we discover this isn’t the case. Bruno is massaging Andy’s ego. In his exchange with Bruno, Andy views 24 of Basquiat’s paintings which unfortunately we never see. Bettany looks out into the audience to “view” Basquiat’s work, as we imagine what Andy sees and watch his expressions of shock, excitement, amazement and jealousy, all in Warhol’s inimitable stylistic phrasing and being. Bettany captures the characteristic Warhol exclamations “gee,” “oh,” and retains enough of the soft spoken and demur air that we’ve seen in films of Andy Warhol that bring us toward acceptance of his portrayal, which deepens as the play embodies their philosophical tension working together.

Bruno is the catalyst for their collaboration. And it is Bruno who comes up with the concept of how to market the exhibition of their works with a poster of both in boxing shorts with Jean-Michel’s chest exposed and Andy’s chest covered in a black T-shirt, as they hold up their boxing gloves ready for their match up of paintings on Mercer Street in New York City.

To persuade a reluctant Andy, Bruno uses flattery and guilt. He chides the avid filmmaker that he hasn’t picked up a brush in years. When Andy shrugs off Bruno’s flattery with self-deprecation that his reputation “is in tatters,” and “no one loves him any more,” Bruno wisely counters Andy’s defense and makes him think. Bruno suggests that it is Andy who doesn’t return the love given to him, an idea that intrigues Andy because it divulges arcane, inner knowledge about his soul which may be accurate. Bruno has hooked Andy toward working with Jean-Michel. But he is completely drawn in when Andy realizes that this is a golden opportunity to employ his skills as a filmmaker and interviewer. He will film their collaboration and record it for posterity.

After Andy leaves Bruno’s gallery, Basquiat keeps his appointment with Bruno and we see how the art dealer works his persuasion to lure Jean-Michel to accept Andy as an artist-partner. Like Andy, Jean-Michel is not convinced. In fact, he is nonplussed at the idea of painting with a world renowned artist and is suspicious and recalcitrant, suggesting that Andy is mechanistic and repetitive and his prints lack soul. With the same push-pull, parry and thrust that he experienced with Andy, Bruno cajoles and uses reverse psychology on Jean-Michel. He is not willing to take “no” for an answer, though Jean-Michel accuses him of exploitation when Bruno suggests the project is monumental and will have “art lovers lined up from the gallery door to JFK.”

Bruno stirs Jean-Michel on collaborating with Andy, using flattery and the unction that Andy really wants to work with Jean-Michael, though we have just witnessed that this is not true. Jean-Michel states he has nothing to say to Andy because they don’t “speak the same languages,” and he is not here to “bring Andy back from the dead.” Bruno, a master of human nature who pings Jean-Michel’s underlying vanity and competitiveness, finally reels him in with the discovery that Andy thinks Jean-Michel is “a threat to his entire understanding of art.”

The humor in both artist’s exchanges with the art dealer is organic, and the presentation of Bettany’s Warhol and Pope’s Basquiat are strikingly similar in their susceptibility to compliments, their egotism, their underlying insecurity with arrogance (Basquiat) and self-disdain (Warhol). As we watch the apparent tensions unfold, it is clear that Warhol and Basquiat may be sparring partners, but theirs is a match that is too coherent and intuitive not to work. Of course the idea that this will bring in tons of cash and, as Basquiat suggests, the bankers will be happy, emphasizes the themes of art’s pure expression versus art exploitation, and art as a business versus the pleasure and necessity to create art which drives both Andy and Basquiat. Meanwhile, as the inveterate money-minded dealer, Bruno encourages this promotional collaboration to harness their ambition and turn it into profits.

During Andy’s and Jean-Michel’s individual exchanges with Bruno dueling for advantage, themes and details in the artists’ lives surface. Andy’s mention of Valerie Solonas’ assassination attempt in 1968 that nearly took his life and caused him to look over his shoulder, expecting to be killed again is poignant and humanizing. The humanizing details continue throughout both acts and help to inform our understanding of the similarities between Warhol and Basquiat in their childhood experiences, for both were influenced by their mothers toward art, drawing and painting.

After the prologue with Bruno, the first act predominately takes place in Andy’s studio as the artists become familiar with each other, discuss their viewpoints, the idea of branding, what Andy’s art attempts and what Jean-Michel attempts with his art. Finally, they agree about what to paint and Andy sneaks in his filming as Jean-Michel paints and answers Andy’s questions. By the second act which takes place in Jean-Michel’s loft/studio/apartment, both artists have become close revealed in the film projections during intermission. At a crucial point in the second act and at Jean-Michel’s suggestion, they challenge each other good naturedly to take off their shirts and expose their wounds.

It is a profound, humbling, bonding act. The icons are human and terribly vulnerable. We see Jean-Michel’s extensive surgical scar where he was injured, run over by a car. He had to recuperate for a long time, a trial which his mother got him through when he was 7-years-old by encouraging him to look at Grey’s Anatomy and draw what he saw to inspire his healing process. And we see Andy’s corset which he must wear to hold his organs in place and above it the long, disfiguring scars criss-crossing his torso, where the surgeons had worked feverishly to save his life from Valerie’s bullet which she shot into him at point blank range.

The second act evolves into an explosion of love and rancor between the two artists. When former girlfriend Maya (Krysta Rodriguez) comes to Jean-Michel’s place to settle up a financial arrangement with Jean-Michael, Andy tells her about their mutual friend Michael Stewart who is in a coma, beaten unrecognizable by cops because he was painting graffiti. Maya returns with the news of Michael’s death and pleads with Basquiat to go to the lawyer’s office with her to give testimony proving the cops murdered Michael. Basquiat refuses. Instead, he gives her the Polaroids of Michael’s mutilated face and body.

Jeremy Pope’s Basquiat transforms into raw nerve endings of emotion in a heart wrenching explanation why he can’t go to the lawyer’s office. The jitters, the nerves, the frenetic energy that need to be displaced because of Jean-Michel’s painful identification with Michael as a fellow sufferer who has just passed is Jeremy Pope’s tour de force throughout the rest of the act.

Basquiat reminds Maya and Andy of the heartless reality of Black racism and oppression evidenced in police brutality against Michael. The spirit of hate and bigotry murdered Michael and that same spirit is ranging to murder him, as he, too, painted graffiti at one point early in his career. Pope conveys Basquiat’s tortured grief at the loss of his beautiful friend. He is torn between wanting to help the Stewart family and preserve his own life and destiny. When Basquiat accuses Andy of indirectly killing Michael, who he was trying to heal with his painting, not understanding, Andy is shocked at Basquiat’s recriminations.

McCarten reveals what painting means to Basquiat and how he perceives art’s power in this tremendous scene that hearkens back to Basquiat’s childhood when he encouraged his own healing by drawing “healthy” organs from illustrations in Grey’s Anatomy. Painting is his way of controlling, resurrecting life, defining power constructs and capturing racism symbolically to effect its change. When Basquiat tries to evoke healing for Michael spiritually, Andy’s commercial, material filming destroys the spiritual power to heal his friend who dies. Thus, for Basquiat painting is totemic and primal, sacred and holy while Andy, tortured by Basquiat’s questions reveals that art to him is an escape from self-loathing into an austere identity which only momentarily eradicates the deformed ugliness he is.

Ironically, at the core of their art, MarCarten suggests they symbolize and do different things. Andy films/records history to understand the creative process and see humanity, while never accepting his own. Basquiat employs the creative process to heal himself and others. One process is not better than the other, nor are they mutually exclusive. As their “collaboration” proves, both are integral to each other. Combined, they establish the inherent beauty and singularity of both.

This incredible scene extends into a dance between Andy and Jean-Michel who pushes Andy to validate and reveal himself as he pretends to film him, though Basquiat has destroyed all of Andy’s films of their collaboration. Once again Bettany’s Warhol and Pope’s Basquiat challenge each other in a rivalry that can never be equal because Andy is not Black. Though he suffers discrimination because he is gay, their bond has limitations. Andy leaves then comes back apologetically though Basquiat has been cruel to him. And it is in the last minutes of the play that there is a touching reconciliation. The inevitability of their lasting artistic achievement is brought to the fore.

To effect the characters, the director’s vision and the creative team’s execution of it works well. Warhol’s and Basquiat’s wigs thanks to Karicean “Karen” Dick & Carol Robinson and Anna Fleischle’s costuming are on-point. Fleischle’s minimalist scenic design of white walls serves to intimate Bischofberger’s gallery, Warhol’s Studio on Broadway and Union Square, and Basquiat’s loft apartment/studio on Great Jones Street. Props and paintings and works and furniture are added and taken away accordingly. Basquiat’s digs in the second act require the greatest set-up, as he lives in cluttered disarray, unlike Andy’s studio which is neat, clean and “almost sterile.”

The second act reveals magnificent writing and magnificent acting. Throughout the concept of modern arts’ evanescence, that “everyone thinks they can do it,” and discussions of art critics attempting to nail down their work then toss it aside, are fascinating and richly profound. That both men were exploited and learned to then exploit themselves to become their own business models has currency for us today. Of course they became masters at self-exploitation. Considering that Basquiat’s brilliant light shined momentarily to leave a massive body of work and Warhol’s frenetic energy blasted an even more massive collection, their painting together was genius.

Because Warhol and Basquiat have been branded with their own mythology and entrepreneurship, understanding who they were, understanding their relationship remains elusive. Such comprehension cannot be gleaned in one play, nor should one expect to. However, McCarten creates a masterwork that Bettany and Pope use as a jumping off point to portray the divine and weak in both characters. They are stunning, beautiful, transcendent. Thus, to describe The Collaboration as a “biodrama,” as some critics have done, is wholly inadequate. Rather the play is McCarten’s vision enhanced by Kwame Kwei-Armah’s sensitive and profound acknowledgement of two artistic geniuses who collided in the tension of trying to do the impossible. And as a result of this collision, they formed something new. They integrated their own styles of art in these partnership paintings that embodied resonating themes at the core of their own lives.

As the final sardonic irony at the play’s conclusion, while Bettany’s Warhol and Pope’s Jean-Michel paint into immortality, we hear the voice of an auctioneer, representative of the art world now on steroids, directional from what it was like when they were alive in the 1980s. Their work together is valued in the multi-millions, the irrevocable exploitation of both.

Kudos to Ben Stanton’s lighting design, Emma Laxton’s sound design, Duncan McLean’s projection design and Ayanna Witter-Johnson’s original music. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2022-23-season/the-collaboration/

‘Between Riverside and Crazy,’ in its Stunning Broadway Premiere

When it premiered Off Broadway at the Atlantic and then moved to 2nd Stage in 2014, Stephen Adly Guirgis’ Between Riverside and Crazy, directed by Austin Pendleton, won a passel of New York City Theater awards in 2015 (New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play, Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Play, Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding New Off Broadway Play). Also, it won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Starring mostly the same cast as in its 2014 outing, the 2022-2023 production appears to be topping itself with solid, incisive direction by Pendleton and sharp ensemble performances led by the mind blowing Stephen McKinley Henderson, who inhabits Pops as sure as he lives and breathes the character’s feisty attitude, edgy humor and earthy sangfroid. Henderson’s performance is a tour de force, a character portrayal of a manipulator able to dodge and parry with the “best” of them to outsmart all comers and “get over” even when he has lost the war and is trying to win his last battle, though the likelihood isn’t in his favor.

Guirgis plies old ground in Between Riverside and Crazy. He examines Black lives that are moving on in the struggle to rise up in New York City, as they attempt to negotiate middle class economics, while the discriminatory city institutions fight them at every turn. In this environment every day is a hustle and the institutions who have hustled Blacks for generations are obvious. However, how does one fight City Hall and still remain in tact? Pops is an old salt and has managed to learn the ropes as a NYC cop. The problem is he lost his wife, his son has just been released from jail and he likes to have a drink or two or three. Can he suppress his wayward impulses, sustain himself and support his son getting back on his feet to prevent Junior’s recidivism?

The play opens with Pops having his breakfast (pie and whiskey-spiked coffee) with Oswaldo (Victor Almanzar in a riveting performance). Oswaldo is a friend of his son Junior’s who clearly is needy and has psychological issues which Guirgis reveals later in the play. Pops’ banter with Oswaldo indicates the situation and relationship between the men. Oswaldo positions Pops as his “Dad,” because he allows him to stay and help him get on his feet without paying rent, though Oswaldo affirms that he wants to and will when he is more flush in his finances. Who Oswaldo is and how he became friends with Junior clarifies as the play progresses. Indeed, they most probably share more than a few crimes.

As a former New York City cop who has been retired after being shot by another cop in a questionable racial incident that Pops has been litigating against the NYPD for eight years, Pops is aware of who Oswaldo is. Interestingly, ironically, he is helping out his son’s friend as a fatherly figure. Of course that isn’t as easy as it appears at the top of the play.

Pops lives in a spacious, valuable, rent-controlled apartment on Riverside Drive in a gentrified area. The apartment whose former structural beauty and interior cared for by Pops’ deceased wife is apparent and fading (scenic design by Walt Spangler). Pops is in your face with Junior’s friends and girlfriend Lulu (the fine Rosa Colon) who he chides for exposing her ample buttocks and breasts and comments about her lack of intelligence to Oswaldo, behind her back as an afterthought. Guirgis has given Pops the bulk of the humorous dialogue and makes sure the other characters that circle him are beholden to him, and give him the proper obeisance, so he might gently insult and dominate them.

Clearly, Pops is witty with tons of street smarts, and we are drawn in by his outgoing nature and backhanded charm. However, Guirgis leaves numerous clues that Pops is into a power dynamic and must have the last word and must have the upper hand in the relationships he has with others. As we watch him “front” and “get over,” we ask to what extent this is part of his hustle and interior nature that he developed as a way to survive? To his credit Guirgis leaves enough ambiguity in his characterizations to suggest the deeper psychology along with the cultural aspects of discrimination without belaboring the themes. We are invited to watch these characters unfold with glimpses into their lives in a light-handed approach that is heavy with meaning, if one wishes to acknowledge it.

Thus, on the one hand Pops’ demeanor is entertaining and hysterical. On the other hand, it is so because Pops is driven to keep others “at bay” and “in their place.” This is the situation that abides until the conclusion, though Guirgis throws twists and divergences in the plot, redirects our attention and makes Pops appear to be the weak one who can’t get out from under his own foibles and issues. Guirgis constructs episodic humorous moments that are surprising and lead to an equally surprising resolution which is totally in character with Pops, whose every nuance, gesture and line delivery are mined brilliantly by Henderson, guided by Pendleton’s deft direction.

Thus, it would appear that Pops has created an environment where secrets are kept and Lulu, Junior and Oswaldo are allowed to take advantage of Pops’ largesse. This is especially true of Junior, who possibly is using his Dad’s apartment to store items that fell off a truck, something Pops turns a blind eye to. As Junior, Common is making his stage debut and he manages to negotiate the complex character’s love/hate relationship with Pops as they spar and “get along” as best they are able because both are dangerously similar in pride, ego and charm. This is so even though they are on the opposite sides of the law and Junior has recently been released from prison.

The principal conflict in Guirgis’ character study occurs after the playwright spins out the expositional dynamics. Pops’ former partner Detective O’Connor (Elizabeth Canavan) and her fiance Lieutenant Caro (J. Anthony Crane in the Tuesday night performance I saw) have a scrumptious dinner that Pops cooks for them. After a lovely repast, Caro delivers a proposition to Pops. Only then do we understand the precarious situation Pops has put himself in. The dire circumstances have been encouraged by Pops’ own negligence and lack of due diligence. He has not kept up with his rent. He has not taken the offer the NYPD has put forth to pay for his pain and suffering (his sexual function has been debilitated) in the litigation. Additionally, Pops faces an eviction spurred on by the building’s tenant complaints, some of which seem sound, but also reveal discrimination.

How has Pops managed to back himself into this corner, though he doesn’t appear to belong in his wife’s wheelchair which he enjoys sitting in and can just as easily get out of? Importantly, Gurgis suggests sub rosa explanations for Pops deteriorated emotional state and his reliance on drinking. Nothing is clear at the outset, but after the visit by O’Connor and Caro, the extent to which Pops has allowed his potential enemies to leverage his present circumstances against him emerges. Will Pops be able to finesse the situation? By the end of Act One when Pops is injured and burglarized, we are convinced that Pops’ weaknesses have overcome him and he is doomed to go the way of his wife.

Guirgis’ Act II heads off in a zany direction which further validates the playwrights’ admiration for the prodigious character he has created in Pops, foibles and all. There is no spoiler alert, here. You’ll just have to see this superb production. A good part of the enjoyment of this premiere is watching Henderson hit every note of Pops’ subtle genius in redirecting those around him to eventually achieve what he wishes. He even bests Church Lady (the funny Maria-Christina Oliveras). Her machinations to “get over” on him which results in a reversal of fortune that is redemptive for both Pops and her are LOL smashing.

The ensemble is top notch and Pendleton’s direction leaves little on the table and is equally stunning. Kudos to the creative team with Alexis Forte’s costume design, Keith Parham’s lighting design, Ryan Rumery’s original music & sound design which are excellent. Gigi Buffington as vocal coach does a great job in assisting the actors in the parlance of the culture of Pops and his satellites so that they are seamlessly authentic and spot-on in their portrayals.

I did have a minor issue with Walt Spangler’s beautiful scenic design. Pops’ apartment revolves on a turntable which limits staging options. Granted that Pops is central to every scene. However, at times the actors’ conversations are directed toward Pops with their backs to the audience. These requires they project or “cheat” in their stance to be seen which at times they did not. This is an instance when the scenic design as lovely as it is didn’t enhance the overall production, but hampered it, a minor point.

Between Riverside and Crazy is a must-see for its performances, ensemble work and fine shepherding by Austin Pendleton. It is in a limited engagement until February 12th unless it is extended. For tickets and times go to their website: https://2st.com/shows/between-riverside-and-crazy#calendar

‘Some Like it Hot’ Fires up the Laughter, Dazzling at the Schubert

One of the more intricately updated movie adaptations on Broadway that sparks a flame that will surely last, Some Like it Hot is perfect for the holiday season and year-round. From start to finish the sensational cast keeps the audience laughing, thanks to enlightened direction, (Casey Nicholaw), seamlessly wrought staging, superb pacing, on-point timing and smashing songs sung by spot-on principals and company.

Performances by standouts J. Harrison Ghee (Jerry/Daphne), Christian Borle (Joe/Josephine), Sugar (Adrianna Hicks), Natasha Yvette Williams (Sweet Sue) and Kevin Del Aguila (Osgood) hurtle the comedy at breakneck speed around the roller coaster turns of plot, mostly familiar to those who have seen the original titular film upon which this two-act musical comedy is based. Currently, Some Like it Hot is at the Sam S. Schubert Theatre without an end-date.

With book by Matthew Lopez and Amber Ruffin, with additional material by Christian Borle and Joe Farrell, music by Marc Shaiman and lyrics by Scott Wittman and Marc Shaiman, Some Like it Hot, mostly through songs unspools the story of two Chicago musicians. Witnesses to a murder by a crime boss and his henchmen, Jerry (J. Harrison Ghee) and Joe (Christian Borle) must leave town to avoid being killed. As they flee for their lives moving from the streets of Chicago to a train journey across country to California, to their hotel destination, the cast joyously sings 10 songs in Act I and 8 songs in Act II.

The strongest numbers meld superlatively with the jazz/blues club and rehearsal scenes and display the wacky characterizations, i.e. Osgood (the marvelous K.J. Hippensteel) and his relationship with Daphne, for maximum humor. The club and rehearsal songs are rollicking, streams of musical electricity that include “I’m California Bound,” “Take It up a Step,” “Zee Bap” and “Some Like it Hot,” and in Act II “Let’s Be Bad,” and “Baby, Let’s Get Good.” The music can’t be beat if you love jazz, blues and a compendium of styles from that era.

The opening speakeasy scene “What Are You Thirsty For,” prepares us for the rousing up-tempo and hot jazz style that characterizes the music of Sweet Sue’s all-girl band. The song, like all of those in the club scenes maintains the high-paced energy which never lets up, thanks in part to Natasha Yvette Williams, whose band conductor Sue rules with a firm hand, is humorous and twits Josephine (Joe) about her age because she looks dowdy and frumpy, in a joke that is milked throughout. In assuming their new roles as women, both Joe and Jerry take pride in their beauty and femininity and are insulted if men “step out of line” and take liberties, or as in the instance of Sweet Sue with Josephine/Joe, feel hurt pride that they do not look pretty and young. Of course the irony that these men are becoming enlightened to what it is really like to be women, pestered and objectified by men is just priceless.