Category Archives: Broadway

‘The Piano Lesson’ is a Striking Revival That Delivers Exceptional Acting, Acute Direction and Prodigious Mastery

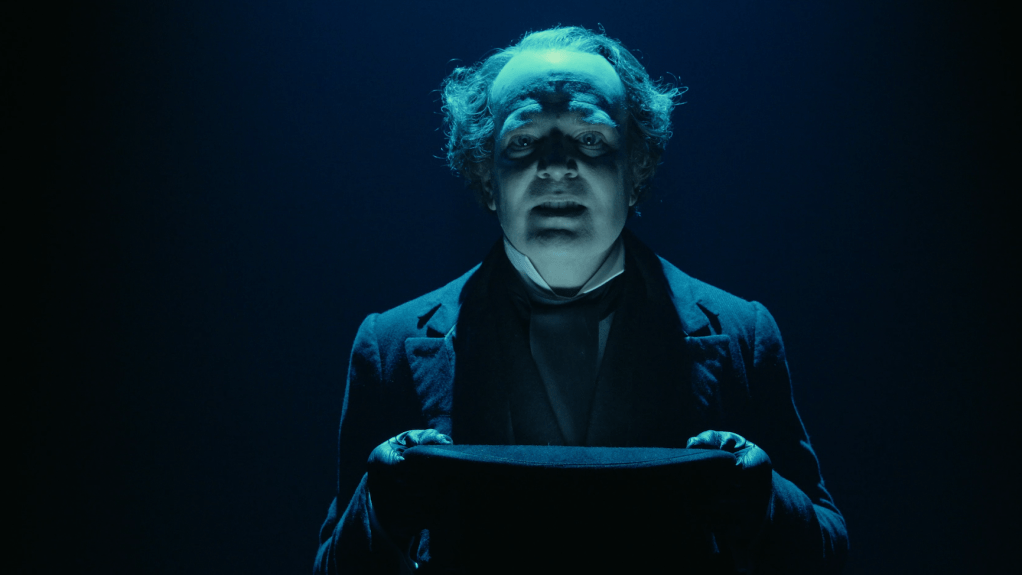

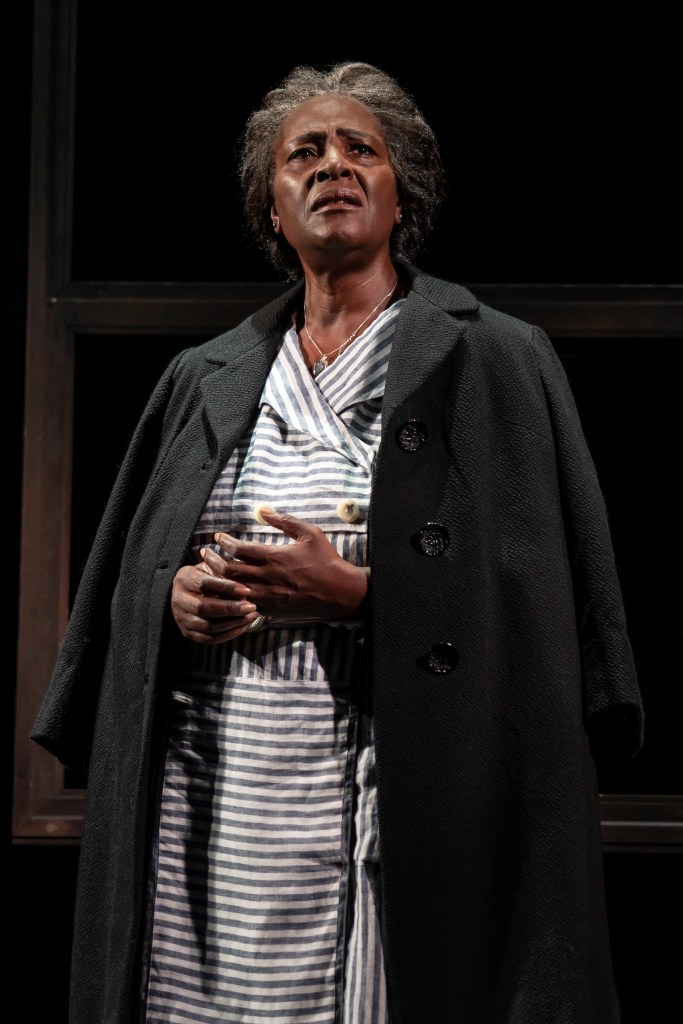

How do we reconcile a past of misery, torment and devastation? Do we bury it or embrace the goodness our ancestors brought to bear as they raised us? Do we take the next steps to rise up to the inner glory they encouraged, or mourn in resentment never exorcising the anguish that seeped into our psyches? In August Wilson’s richly crafted Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Piano Lesson, currently running at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, the character Berniece (superbly portrayed by Danielle Brooks) must reconcile herself to her past and become the conduit that translates legacy into new beginnings for her family and her daughter.

The Piano Lesson symbolizes how African Americans must approach their painful history of slavery as a planting field which may give birth to strong generations that carry new hope and opportunity for a positive future. Additionally, in this production directed by Latanya Richardson Jackson, Wilson suggests what that future might be with an uplifting conclusion where family understanding and unity are restored after nefarious forces steeped in colonial, paternalistic folkways and institutional racism, sought to keep the family divided and conquered.

August Wilson’s play debuted on Broadway in 1990, not only winning the Pulitzer Prize but also winning the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Play, as well as the New York Critic’s Circle Award for Best Play. The Piano Lesson which takes place in Pittsburgh, 1936 is one in a collection of 10 plays in Wilson’s American Century Cycle. Each of the plays, set in a different decade, chronicles African American struggles and triumphs as various families move away from the remnants of slavery and its impact from 1900 through the 1990s. The work has enjoyed three revivals, one Off Broadway in 2013 and the two Broadway outings (1990, 2022).

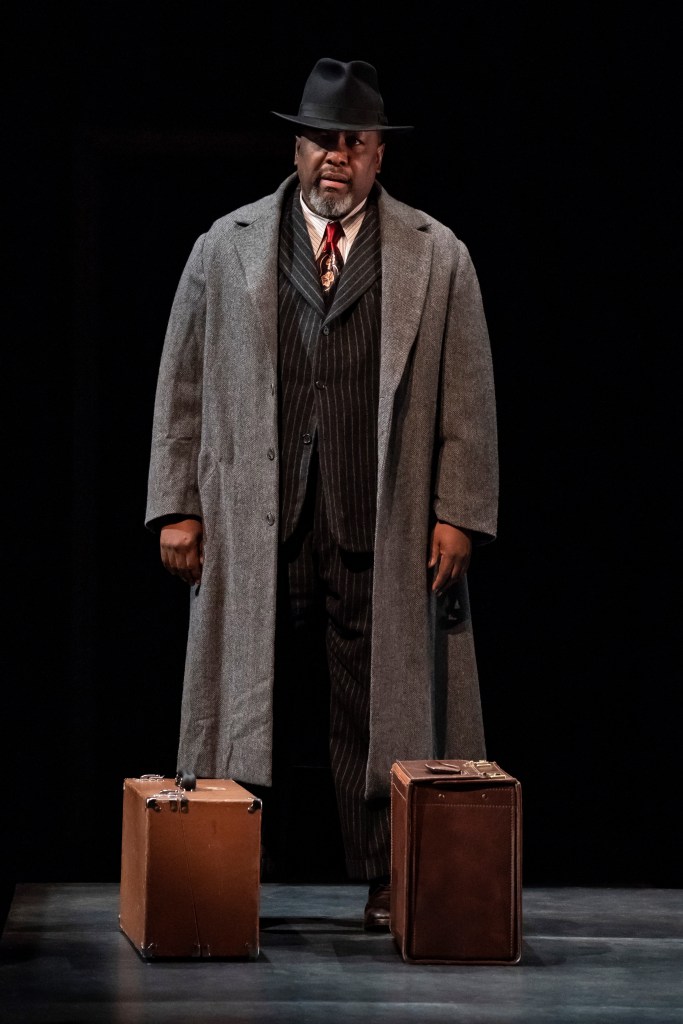

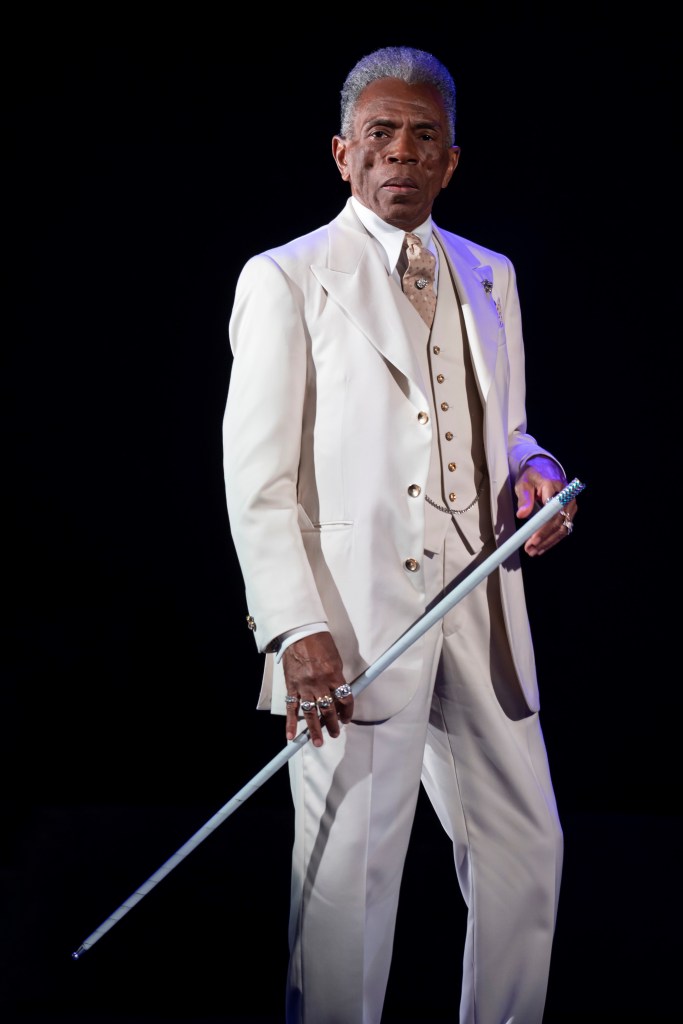

This outstanding revival features seminal performances by a superb ensemble and a clarifying vision about the play by the director. Each actor brings vitality and authentically to manifest the roiling fear and oppression that still hangs over the lives of characters Berniece (Danielle Brooks) Boy Willie (John David Washington) and family uncles Doaker (Samuel L. Jackson) and Wining Boy (Michael Potts) as they attempt to move beyond their traumatic past. It is a slavery past where ancestors saw toil and heartache and a recent past where Berniece and her family saw violence, bloodshed and anything but a peaceful passing to ancestral graves.

Events come to a head when Boy Willie visits the family for the first time in three years since Berniece lost her husband Crawley. Boy Willie comes with a vital personal mission so he braves his sister Berniece’s ire because he is at a turning point in his life. Berniece and Boy Willie have been estranged because she blames him for Crawley’s death. Tired of sharecropping for others, Boy Willie leaps when he is offered an opportunity where he, too, can embrace the “American Dream.” In an ironic twist he would be purchasing land his ancestors worked as slaves made available after the slave master’s descendant, the head of the Sutter family, fell down a well and died. Boy Willie’s purchase would allow him to end being exploited by others so he might work to lift himself to a better life.

However, he needs to raise more cash to complete the land deal, so he intends to sell their family heirloom, a beautifully carved upright piano which is housed in Uncle Doaker’s Pittsburgh home where Berniece and her 11-year-old daughter live. As is often the case with inheritances, there are family squabbles about how to dispose of various items. The piano not only is valuable materially, it symbolizes the family’s history and legacy, which is both beautiful and terrible. An ancestor carved the faces of family members on it to soothe the slave master’s wife who was missing her slaves that were traded for the piano. Over the years, the piano has become the family totem that conveys a spiritual weight and emblematic preciousness. Wilson signifies this when Boy Willie and friend Lymon find it nearly impossible to lift by themselves.

Berniece understands the piano’s significance to the depths of her soul and refuses to allow Boy Willie to remove it. For seven years after their mother died, Berniece stopped playing it to honor her mother’s remembrance. Though only Maretha (played by Jurnee Swan at the performance I saw) and Uncle Wining Boy play it, Berniece justifies keeping it because of Mama Ola Charles. Mama Ola daily polished it “til her hands bled, then rubbed the blood in…mixed it up with the rest of the blood on it” and mourned over the tragic loss of her husband, Boy Charles who was murdered after he stole it and hid it to retain its ownership. He believed if the Sutter family kept the piano, they symbolically “lorded” it over the Charles family, who they would oppress as their ersatz slaves, if not physically, then psychically and emotionally.

Gradually, Samuel L. Jackson’s Doaker reveals the story of the piano’s history since slavery days. With understated reverence as an explanation why Berniece will never let it go, he discusses how the carvings of each ancestor and their stories reside there as a remembrance of their identity and the sacrificial death of his brother Boy Charles, who first imbued the piano with the symbolic and spiritual significance of their family’s legacy of forward momentum.

Jackson’s Doaker and Danielle Brooks’ Berniece superbly translate the importance of this magical object with nuance and power that gives rise to our understanding why the ancestral spirits are hovering in the piano’s majesty in a battle that becomes otherworldly between the Sutter and the Charles family. It is a battle which has been continuing revealed at the top of the play with Boy Willie’s excited, impassioned entrance and reflected in Beowulf Boritt’s incredible set of Doaker’s simple four room house whose spare roof timbers exposed to the sky appear to be split and separating.

Indeed, the Charles family is a house divided by disagreement, disharmony and mourning tied in and caused by the racial discrimination, and inequitable economic opportunities intended to keep African Americans entrenched in poverty and peonage. To be free of Sutter oppression the Charles family must move away from the Sutters’ (symbolic of white racists) murderous, thieving behaviors, exploitive folkways and lack of empathy for others. They must free themselves from materialism, selfishness and criminality that has destroyed their humanity, as Brook’s Berniece expresses in her indictment of the men in her immediate family, including her dead husband Crawley.

Boy Willie’s presence at this point in time after Sutter is found at the bottom of a well is intriguing. Has Sutter’s wicked ghost driven him up to trouble Berniece about the piano despite its legacy? Or does he just want to make a better life for himself as he suggests? Berniece believes he pushed Sutter to his death, knowing the Sutter land would be put up for sale. Though Washington’s Boy Willie makes a convincing argument that he is not a murderer and Pott’s colorful Wining Boy suggests it’s the vengeful “Ghosts of the Yellow Dog” that caused Sutter’s fall to his death, Berniece is not convinced. Boy Willie’s presence has brought confusion and turmoil, exceptionally rendered by Washington’s Boy Willie, who appears so impassioned about selling the piano, he acts like a man possessed.

Additionally, Boy Willie’s obviation of the importance of the piano as their family legacy is answered with his apology to Berniece as if that is enough because he will sell it regardless. That answer isn’t enough for her. However, Boy Willie insists forcefully almost manically that he will use the land and make something with it, even though the deal is by word of mouth and could be another bamboozle by the Sutter family as Uncle Wining Boy suggests.

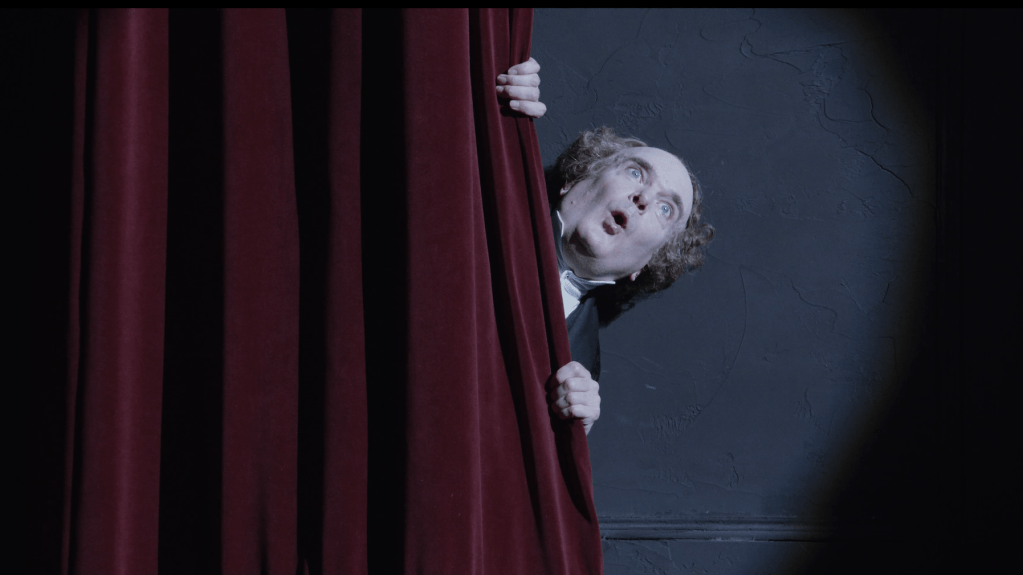

That the ghost of Sutter appears to members of the family around the same time that Boy Willie appears is more than a coincidence. That Boy Willie is the only one who doesn’t see the ghost is also more than a coincidence. Berniece, Doaker, Maretha and Wining Boy see the ghost who has been manifesting on the second floor above where Boritt’s roof timbers separate, threatening with well-paced grinding sounds (Scott Lehrer) to split the house up and fragment it completely.

Why doesn’t Boy Willie see Sutter’s ghost? Has Boy Willie become an instrument of the Sutter family, influenced/possessed by Sutter’s ghost to continue the tradition of theft, exploitation and bloodshed (the chains of slavery days) luring Boy Willie with the dream of being “his own boss?” The longer Boy Willie stays to sell a truck load of watermelons, the more the arguing and airing of grievances continues, intermingled with wonderful songs they sing, the first led by Jackson’s Doaker and the last by Potts’ Wining Boy who made a profitable living which he couldn’t sustain playing piano and cutting a few records.

However, nothing will ameliorate Boy Willie’s lust for the money the piano will bring. Finally, when push comes to shove, Berniece and Doaker do take out their guns ready to shoot Boy Willie if he and his friend Lymon (Doron JePaul Mitchell when I saw the show) remove the piano.

Brooks’ Berniece is so fervent that we believe she will shoot her brother to protect her ancestors’ legacy whose symbolism and spiritual strength she has embraced during Boy Willie’s importuning her to give it up. Washington’s Boy Willie is every inch her equal, stoked by the Sutter relative with the lure of land and his own ambition, like the Biblical Esau, willing to sell his birthright without any guarantees. Brooks and Washington are perfect foils and deliver amazing performances. Jackson’s Doaker and Pott’s Uncle Wining Boy present the stabilizing, humorous counterbalance to the frenzied brother and sister. If not for Wining Boy’s playing the piano at that heightened moment when Berniece has the gun, she would shoot Boy Willie, and Sutter’s ghost would have triumphed, completely destroying the family. Jackson’s direction and the timing of Potts and Samuel L. Jackson’s interference and distractions round out the incredible drama that moves toward the last scene of the play.

It is then that all the characters acknowledge the ghost of Sutter’s presence in the grinding sound of the house being pulled asunder by the warring spirits which also represent the values which the families prize. These are the values which Boy Willie must decide on. Should he be like the Sutters or raise up his own family’s legacy as Doaker has learned to do as a trainman and as Berniece has done steadfastly living one day at a time? Does Boy Willie have the resolve to shake off destructive forces and slowly carve out a life for himself with a lasting peace? At the top of the play Washington’s Boy Willie is so possessed by the Sutter’s offer and righting the past exploitation of his family, he can’t wait to follow them down the same pathways. However, Washington’s Boy Willie does change and is redirected.

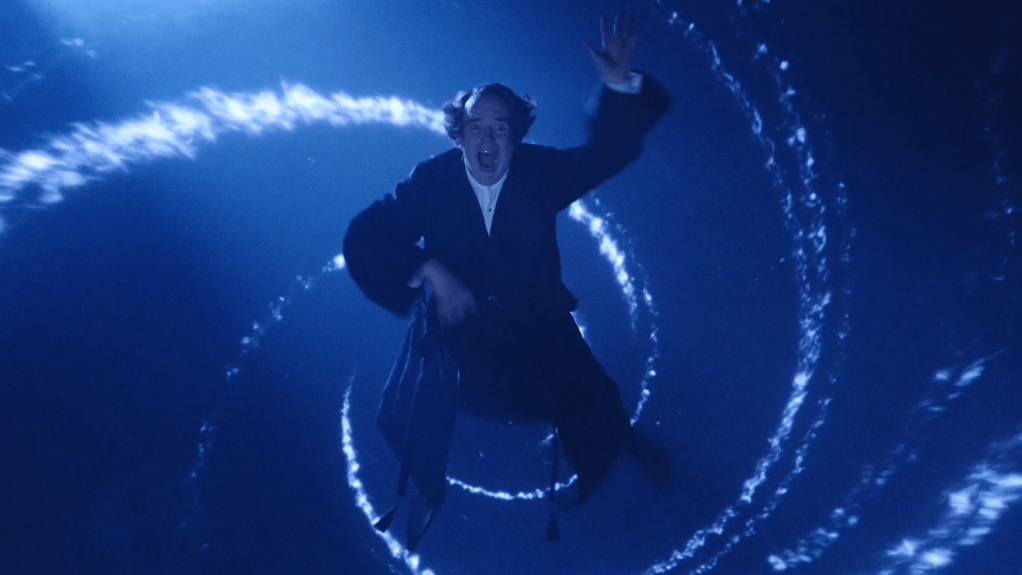

Encouraged by everyone who feels the presence of Sutter’s ghost, preacher Avery (Trai Byers-another superb performance) who Berniece has been seeing, attempts to cast out the pernicious Sutter. He fails. Only Berniece calling on the help of her ancestors’ spirits who assist in the spiritual battle overcomes the ghost of Sutter’s presence and hold over their family. As she sings and plays the piano, on the second floor we watch the impact of her prayers and the Charles family’s spirits on Boy Willie as Washington manifests the struggle with Sutter’s ghost. As his body arches over then releases, we note that Sutter’s ghost, its tormenting lures that possessed Boy Willie leave. The two siblings are finally in agreement with Doaker and Wining Boy that what Sutter represents has no place in their family. As it leaves Boy Willie, miraculously, the house is made whole. With a grinding sound and the final sighting and restitution of the Ghosts of the Yellow Dog (you have to see the play to understand what happens) the separated timbers rejoin. It’s an incredible effect and magnificent, symbolic realization of Wilson’s immutable themes, about family unity in reconciliation with the past to move forward, thanks to the creative team, wonderful actors and Jackson’s direction.

Jackson’s staging and use of special effects (Jeff’s Sugg’s projection design, Lehrer’s sound design, Japhy Weideman’s lighting design, Boritt’s fabulous set) convey Boy Willie’s struggle, exorcism and redemption from the tradition of oppression, bloodshed and materialistic selfishness that have corrupted the Sutters and work to corrupt him and completely divide his family. He is only able to gain strength to be released when Brooks’ Berniece accepts how the legacy of past can be turned into a positive future by becoming the conduit of the ancestral spirits. It is their beauty, sanctity and strength that rise up to lead her, Maretha and the others forward, if they allow themselves to be led.

Boy Willie and Berniece join hands in unity. His demeanor transforms into calmness. He no longer wants to sell the piano, understanding that his family history and his identity are in unity. With the house returned to wholeness, the wicked impulses will no more occlude the lives of Berniece, Boy Willie and the others. Now they can move forward and carve their own history in the reality of their lives.

Throughout Wilson raises questions whether Boy Willie got revenge on Sutter for having his father burned alive and the question of whether he killed him to get the land in an ironic triumph. Another question is whether the Sutters are serious about selling the land to Boy Willie given the history between the two families. In the production these questions are emphasized by director Jackson’s vision of the themes and characterizations of this complicated work brought to a phenomenal apotheosis at the conclusion. However, as in life, ambuity is the spice that keeps us enthralled along with the chilling presence of the supernatural hovering.

This is a one of a kind production that exceptionally realizes August Wilson’s intent with every fiber of the artists’ prodigious efforts. I have nothing but praise for what they have done and will do for the run of the play.

For tickets and times to see this living masterpiece go to their website: https://pianolessonplay.com/

‘Ohio State Murders,’ Audra McDonald’s Performance is Stunning in This Exceptional Production

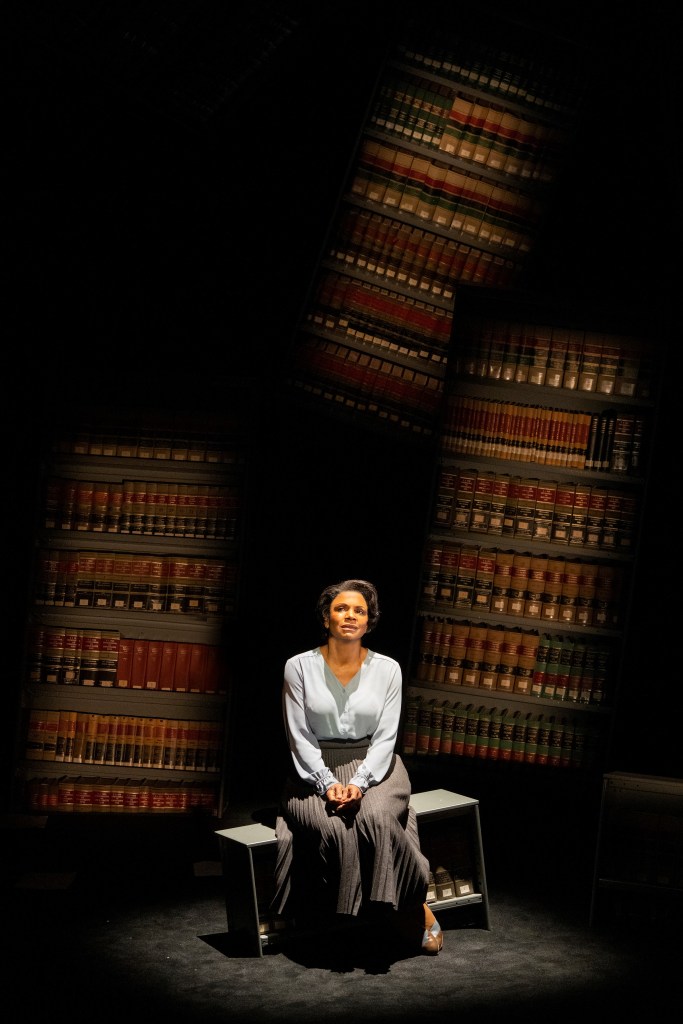

For her first Broadway outing Adrienne Kennedy’s Ohio State Murders has been launched by six-time Tony award winner Audra McDonald into the heavens, and into history with a magnificent, complexly wrought and richly emotional performance. The taut, concise drama about racism, sexism, emotional devastation and the ability to triumph with quiet resolution is directed by Kenny Leon and currently runs at the James Earl Jones Theatre until 12 February. It is a must-see for McDonald’s measured, brilliantly nuanced portrayal of Suzanne Alexander, who tells the story of budding writer Suzanne, in a surreally configured narrative that blends time frames and requires astute listening and thinking, as it enthralls and surprises.

This type of work is typical of Kennedy whose 1964 Funnyhouse of a Negro won an Obie Award. That was the first of many accolades for a woman who writes in multiple genres and whose dramas evoke avant garde presentations and lyrically poetic narratives that are haunting and stylistically striking. As one who explores race in America and has contributed to literature, poetry and drama expressing the Black woman’s experience without rhetoric, but with illuminating, symbolic, word crafting power, Kennedy has been included in the Theater Hall of Fame. In 2022 she received the Gold Medal for Drama from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The Gold Medal for Drama is awarded every six years and is not bestowed lightly; only 16 individuals including Eugene O’Neill have been so honored.

This production of Ohio State Murders remains true to Kennedy’s wistful, understated approach to the dramatic, moving along an arc of alternating emotional revelation and suppression in the expose of her characters and their traumatic experiences. Leon and McDonald have teased out a 75 minute production with no intermission, intricate and profound, as Kennedy references and parallels other works of literature to carry glimpses of her characters’ complexity without clearly delineating the specifics of their behaviors. In the play much is suggested, little is clarified. Toward the unwired conclusion we find out a brief description of how the murders occurred and by whom. The details and the motivations are distilled in a few sentences with a crashing blow.

Much is opaque, laden with sub rosa emotion, depression, heartbreak and quiet reflection couched in remembrances. The most crucial matters are obviated. The intimacy between the two principals which may or may not be glorious or tragic is invisible. That is Kennedy’s astounding feat. Much is left to our imaginations. We can only surmise how, when and where Suzanne and Robert Hampshire (Bryce Pinkham in a rich, understated and austere portrayal) who becomes “Bobby” got together and coupled when Suzanne supposedly visited his house. Their relationship mirrors that of the characters in Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy. It is this novel which first brings the professor and student together in mutual admiration over a brilliant paper Suzanne writes and he praises.

What is mesmerizing and phenomenal about Kennedy’s work is how and why McDonald’s Suzanne follows a process of revelation not with a linear, chronological storytelling structure, but with an uncertain, in the moment remembering. McDonald moves “through a glass darkly,” unraveling recollections, as her character carefully unspools what happened, sees it anew as it unfolds in her memory, then responds to the old and new emotions the recalled memories create.

Audra McDonald is extraordinary as Suzanne Alexander, who has returned to her alma mater to discuss her own writing which has been published and about which there are questions concerning the choice of her violent images. The frame of Suzanne’s lecture is in the present and begins and ends the play. By the conclusion Suzanne has answered the questions. Kennedy’s circuitous narrative winds through flashback as Suzanne relates her experiences at Ohio State when she was a freshman and her movements were dictated by the bigotry that impacted her life there.

In the flashback McDonald’s Suzanne leaps into the difficult task of familiarizing us with the campus and environs, the discrimination, her dorm, roommate Iris Ann (Abigail Stephenson) and others (portrayed by Lizan Mitchell and Mister Fitzgerald), all vital to understanding Suzanne’s story about the violence in her writing. Importantly, McDonald’s Suzanne begins with what is most personal to her, the new world she discovers in her English classes. These are taught by Robert Hampshire, (the astonishing Bryce Pinkham) a professor new to the college. Reading in wonder and listening to his lectures, Suzanne’s fascination with literature, writing and criticism blossoms under his tutelage.

Within the main flashback Kennedy moves forward and backward, not allowing time to delineate what happened, but rather allowing Suzanne’s emotional memories to lead her storytelling. After authorities expel her from Ohio State, she lives with her Aunt and then returns with her babies to work and live with a family friend in the hope of finishing her education. During this recollection she refers to the time when she lived in the dorm and was disdained by the other girls.

Kennedy anchors the sequence of events in time by using the names of individuals Suzanne meets. For example when she returns after she has been expelled, she meets David (Mister Fitzgerald) who she dates and eventually marries after the Ohio State murders. What keeps us engrossed is how Suzanne fluidly merges time fragments within the years she was at the college. She digresses and jumps in memory as she retells the story, as if escaping from emotion in a repressive flash forward, until she can resume her composure. At the conclusion, Suzanne references the murders of her babies.

Thus, with acute, truncated description that is both poetic and imagistic, McDonald’s Suzanne slowly breaks our hearts. McDonald elucidates every word, every phrase, imbuing it with Suzanne’s particular, rich meaning. Though the character is psychologically blinded and perhaps refuses to initially accept who the killer of her babies might be, there is the uncertainty that she may know all along, but is loathe to admit it to her self, because it is incredibly painful. At the conclusion when she reveals the murderer’s identity and events surrounding both murders, she is remote and cold, as is the snow falling behind outside the crevasse. At that segment McDonald’s unemotional rendering triggers our imaginations. In a flash we understand the what and why. We receive the knowledge as a gut-wrenching blow. Fear has encouraged the murderer in a culture whose violence and racism bathes its citizens in hatred.

When McDonald’s Suzanne Alexander brings us back to the present as she pulls us up with her from the recesses of her memory, we are shocked again. We have been gripped and enthralled, swept up in the events of tragedy and sorrow, senseless violence and loss. The question of why bloody imagery is in Suzanne’s writing has been answered. But many more questions have been raised. For example, in an environment of learning and erudition, how is the murder of innocents possible? Isn’t education supposed to help individuals transcend impulses that are hateful and violent? Kennedy’s themes are horrifically current, underscored by mass shootings in Ulvade, Texas and other schools and colleges across the nation since this play was written (1992). At the heart of such murdering is racism, white domestic terrorism, bigotry, hatred, inhumanity.

The other players appear briefly to enhance Suzanne’s remembrances. Pinkham’s precisely carved professor Hampshire reveals all the clues to his nature and future actions in the passages he reads to his classes from the Hardy novel, then Beowuf and in references to King Arthur and the symbol of the “abyss” he discusses in two lectures Suzanne attends. All, he delivers tellingly with increasing foreboding. Indeed, the passages are revelatory of what he is experiencing symbolically in his soul and psyche. When Suzanne describes his physical presence during the last lecture, when she states he is looking weaker than he did when he taught his English classes, it is a clue. Pinkham’s Hampshire is superbly portrayed with intimations of the quiet, profound and troubled depths of the character’s inner state of mind.

Importantly, Kennedy, through Suzanne’s revelations about the university when she was a freshman, indicates the racism of the student body as well as the bigotry of the officials and faculty, which Black students like Suzanne and Iris must overcome. There is nothing overt. There are no insults and epithets. All is equivocal, but Suzanne feels the hatred and the injustice regarding unequal opportunities.

For example it is assumed that she cannot “handle” the literature classes and must go through trial classes to judge whether she is capable of advanced work as an English major. When she tells professor Hampshire, he insists that this shouldn’t be happening. Nevertheless, he has no power to change her circumstances, though he has supported and encouraged her writing. The college’s bigotry is entrenched, as she and other Black women are discouraged in their studies and forced out surreptitiously so that they cannot complain or protest.

Kenny Leon’s vision complements Kennedy’s play. It is imagistic, minimalistic and surreal, thanks to Beowulf Boritt’s scenic design, Jeff Sugg’s projection design, Allen Lee Hughes lighting design and Justin Ellington’s sound design. At the top of the play there are two worlds. We see black and white projections of of WWII and the aftermath through a v-shaped crevasse that divides the outside culture and the interior of the college in the library symbolized by faux book cases. These are suspended in the air and move around symbolically following what Suzanne discusses and describes.

The books are a persistent irony and heavy with meaning. They sometimes serve as a backdrop for projections, for example to label areas of the campus. On the one hand they represent a lure to Suzanne who venerates literature. They suggest the amalgam of learning that is supposed to educate and improve the culture and society. However, the bigoted keepers of knowledge in their “ivory” towers use them as weapons of exclusion and inhumanity, psychologically and emotionally, harming Blacks and others who are not white or who are considered inferior. Leon’s vision and the artistic team’s infusion of this symbolism throughout the play are superb.

In the instance of the one individual who appreciates Suzanne’s writing, the situation becomes twisted and that too, becomes weaponized against her. However, that she has been invited back to her alma mater all those years later to discuss her writing indicates the strength of her character to overcome the incredible suffering she endured. At the conclusion of her talk in the present she reveals her inner power to leap over the obstacles the bigoted college officials put before her. Her return so many years later is indeed a triumph.

Leon and the creative team take the symbolism of rejection, isolation, emotional coldness and inhumanity and bring it from the outdoors to the indoors. Beyond the crevasse in the wintertime environment, the snow falls during Suzanne’s description of events. Eventually, by the end of the play, the exterior and interior merge. The violence we saw at the top of the play in pictures of the War and its aftermath has spread to Ohio State. The snow falls indoors. Finally, Suzanne Alexander is able to publicly speak of it openly and honestly after discovering there was a cover-up of the truth that even her father agreed to out of shame and humiliation.

Ohio State Murders is a historic event that should not be missed. When you see it, listen for the interview of Adrienne Kennedy before the play begins as the audience is seated. She discusses her education at Ohio State and the attitudes of the faculty and college staff. Life informs art as is the case with Adrienne Kennedy’s wonderful avant garde play and this magnificent production.

For tickets and times to to their website: https://ohiostatemurdersbroadway.com/

‘Ain’t No Mo,’ the Uproarious Satire Explodes With Brilliance on Broadway

Ain’t No Mo which premiered at The Public Theater in 2019 brings its scathing, sardonic wit and wisdom to Broadway in a broader, handsomer, electrically paced production with incredible performances and extraordinary, complex dynamism. Presented by a host of producing partners with Lee Daniels topping the list and The Public Theater end-stopping it, Jordan E. Cooper’s brilliance now can be appreciated by a wider audience. Directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, the production shines brightly with the creative team of Scott Pask (scenic design) Emilio Sosa (costume design) Adam Honore, who also was responsible for lighting design in the Public Theater production, Jonathan Deans and Taylor Williams (sound design) and Mia M. Neal (hair & wig design).

The tenor, structure and characterizations which send up Black cultural attitudes and systemic white institutional racism and fascism in Cooper’s excoriating farce and brash, in-your face cataclysm of vignettes, remain essentially the same as the Public’s production which I adored and thought incredibly trenchant (https://wordpress.com/posts/caroleditosti.com?s=ain%27t+no+mo). Based on the premise of the political collapse of the country with Putin installing Donald Trump as president (my opinion as per the Mueller Report) as the main conceit of the play, the government offers a one-way flight back to Africa for all Blacks.

This was a perfect trope in 2019 and still is. Though we have a different administration in the presidency, the same pernicious elements that uplift oppression and inequity refuse to submit to the constitution which safeguards Black citizens and all citizens’ rights. Indeed, since 2019 the villians are hell bent to vitiate as many of our rights as they can. So Cooper’s play is tremendously vital as a clarion call against white supremacist tyranny and despotism at the heart of Trumpism and Republicans’ silent agreement with it.

Cooper attempts a few updates in this production since 2019. He references Black Lives Matter and Vice President Kamala Harris. However, he omits references to the horrific changes in the political climate which has worsened. Nor does he reference the Biden presidency which has sought to reverse every perverse corruption the Trump presidency and Republican party in silent complicity wrought on the country. Trump’s blasphemy of democracy, the January 6th insurrection and COVID botch job (read Bob Woodward’s book Rage) where Trump wittingly exacerbated the proliferation of the virus, killing the most vulnerable communities (persons of color, the elderly) are not mentioned in this production. The updates are unnecessary because Cooper’s themes are more current than ever. In fact they are prescient and hilariously frightening.

The Trump Republicans have continued their fascism and racism with a new vengeance against the Democratic Party which appears to stand for democracy and accountability. At this writing the entire Republican Party has not raised the hue and cry necessary to condemn Trump’s association with two individuals who support white supremacy, Nazis and in particular one individual’s praise of Hitler as a Holocaust denier.

Such white supremacist oppression and outright tyranny are the key points of Ain’t No Mo which suggests truth in ridicule and doesn’t posit simplistic solutions. Cooper’s genius with Stevie Walker-Webb’s superb director’s illumination REPRESENT metaphorically. Within the high-anxiety, farcical elements of the play are the roiling currents of fear and anxiety that reveal what it is to be black in the United States today, regardless of whichever black socioeconomic class one fits into.

This is especially so after the January 6th insurrection, 1,100,000 pandemic deaths and the screaming lies of white supremacist terrorist QAnon politicos like Louis Gomer, Marjorie Taylor Green and fist pumping Josh Hawley. It is especially so as Trump acolytes whitewash violent behaviors as patriotic expressions of freedom, in a cover-up of what they actually are, crimes against humanity and an attempt to destroy the constitution and the rule of law which holds white supremacist terrorist criminals like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys and their encouragers (Trump’s allies) accountable.

Thus, Cooper’s prologue set in a local black church in 2008 at a metaphoric funeral service of Brother Righttocomplain is beyond perfect. Pastor Freeman, the wonderful Marchant Davis, proclaims that the election of black president Barack Obama will save the black community and remove their need to protest injustice, inequity, police brutality and lynchings, and racial hatreds. Parishioners (Fedna Jacquet, Shannon Matesky, Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Crystal Lucas-Perry) dressed in tight white dresses, thanks to Emilio Sosa’s outrageously funny costume design, scream and shout the glory. These congregants affirm with Pastor Freeman that the “light-skinned” (an irony) Black president will solve all their problems as their very own messiah whose freeing power they “own.”

Cooper’s memes and jokes are acutely ironic and a veritable laugh riot. For example he affirms that Obama is their “ni&&er” and as such there “ain’t no mo discrimination, ain’t no mo holleration, ain’t gone be NO more haterration…” The good reverend lists an end to every conceivable example of racist terror visited upon Blacks since the Civil War because with a Black president, abuse of the Black race by an unjust government will now stop. Of course, this is an irony because learned behavior and systemic institutional racism is so complex and entrenched, everyone in the nation must work very hard to overcome it. Given the pockets of prejudice and discrimination even in blue states, this is easier said than done. Cooper illustrates this beautifully by the conclusion of the opening scene.

With the burial of Brother Righttocomplain, “Freeman” preaches “ain’t no mo strife, no more marches to be led, no more tears to be shed…” in celebration of a real “going home party.” Of course, when Pastor Freeman hears gunfire as the parishioners praise, sing and dance, reality makes its ugly appearance. With sirens, cop cars’ flashing lights and gun shots, the future descends during the Obama presidency and afterward to the annihilating Trump presidency.

Above the shouts of praise Marchand’s Freeman hears the overwhelming news reports of the Flint water crisis, deaths of Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, Aiyana Jones, Rekia Boyd, Jordan Davis, Alton Sterling, The Charleston Nine and countless others. The reports reveal Freeman’s overestimation of Obama’s power as a Black president to mitigate racial hatreds and alleviate the social oppression Blacks experience every day. The same discrimination and violence raises its ugly head, despite President Obama’s best efforts to stop it. So the foreboding harbinger of the Trump presidency’s return to Jim Crow 2.0 terrors hover, unless blacks hop on those flights to Africa on African American Airlines. If they evacuate, they will save their lives. If they stay, they lose everything including their black identity and will end up dead or in prison.

Of course Cooper’s Africa evacuation is what President Abraham Lincoln suggested as a way to solve the “negro question” after the Civil War was over. However, Frederick Douglass stood up to Lincoln and vociferously opposed leaving because the United States was their country since 1619, and their association would never be African because their tribal history had been taken from them.

As a solution to the hell of Black America’s unequal treatment under the law, evacuation to Africa is Cooper’s over-the-top response. It is a double irony considering that once again, Blacks are introduced to a new form of dispossession, alienation, abandonment and diaspora, while the oppressive white culture “owns” all of the historical contributions Blacks have made in the arts, sciences, government, technology, industry and every field imaginable. In the play African Americans’ contributions reside metaphorically in a lovely bag which flight attendant Peaches (the inimitable Jordan E. Cooper) tries to take with her as she attempts to board the flight. But symbolically, the bag cannot be removed to Africa. And trying to leave with it, Peaches misses the flight and loses her identity and everything she’s fought for as an American. She is reduced to the state of those who survived the Middle Passage and were set up to be auctioned off as slaves. But she is “keeper” of the bag and recognizes that she is left to represent Black culture and identity.

Another key point Cooper makes with the symbolism of the “bag” is that the greatest Black contributions have been forged in the crucible of slavery and subsequent decades of oppression as Blacks and the culture have changed laws to be more equitable. Black contributions are as indelible to who Americans are as a culture and society as the Native Indian lands are the foundation upon which this nation has been built and has prospered. Though white oppression and white supremacist tyranny vaults its own greatness in lies, ignoring such contributions, it is a dangerous oversight and underestimation of Black energy, vitality and creativity. American greatness is in its diversity, and the culture and society will thrive if no one is left behind or evacuated. We must work together and seek equity for all to be great (an underlying theme of Cooper’s play).

After the opening prologue the play’s structure alternates between vignettes of various Black Americans’ response to escape to Africa and Peaches’ growing frustration boarding passengers under a deadline as an exit strategy from the hell of the coming white oppression. Cooper’s Peaches is wonderful as the wired, loud, candid, funny flight attendant who prods her passengers with the consequences of staying: prison and confiscation of everything they own or death (transmogrification). With each vignette we are apprised of the oppression Blacks have been conditioned to which is the foremost reason why Blacks should leave.

In the “Circle of Life” sequence which takes place at a clinic (since Roe vs. Wade was overturned with Dobbs, this is a particularly poignant scene) we watch the digital counter enumerate that are millions in line to terminate their pregnancies rather than give birth to a child whose days are numbered. Surely odds are they will end up as a statistic of police brutality, gang violence or other casualty of an oppressive culture which has come to kill those who drive or walk “while black.” Damien (Marchant Davis) tries to convince the pregnant Trisha (Fedna Jacquet) to keep his child rather than abort it. However, he is a spirit, shot to death, so Trisha who waits with another woman for almost two months finally goes into the room for the procedure as the plane arrives to begin boarding passengers in a humorous end of the scene as one pregnant woman thinks the plane is filled with the “9/11 bit*&es,” coming for their heads.

In a revelation of how Black identity is twisted and nullified by the culture, “The Real Baby Momas of the Southside” is a hysterical parody of any of the puerile reality series which reduce women to silly, gossipy, back-biting, angry, fools, whether black or white, as “benign” entertainment value. God forbid if this were a political show which demonstrated their intelligence and erudition. Instead, memes of what Black identity means come to the fore in this humorous and drop-dead serious send-up of shows which exploit the idea of “being Black.” Some of the funniest lines come when the women are off camera (the cameramen are white) and we discover that they don’t have children and speak without accents and epithets. We see the show is a blind to please and brainwash the audience, who enjoys seeing how “low-class” Black women are. Meanwhile, there are other ways of being, but this isn’t a show about how strong, forthright, powerful and intelligent Black women are.

“The lighter the skin, the better” is a reality Blacks have had to deal with because of white fascist physical mores. The trend has morphed over the decades into a perverse reverse. Other ethnic groups including whites have embraced the “Black ethos” in a perverse acceptance of only the superficiality of “being black” without accepting or recognizing any of the horrific sacrifices Blacks have made over their 400-year history in this nation. Cooper’s beautiful example of this appears on steroids with the character Rachonda, whose real name is Rachel (Shannon Matesky). She is a baby mama the others reject because she is white and is going through transracial treatments to become Black. When she is called out on it in a LOL moment by Tracy (Ebony Marshall-Oliver), Kendra (Fedna Jacquet) and Karen (Crystal Lucas-Perry), she reveals that she has no clue about Black American sacrifices and and just wants to ride the current wave of Black female “cool,” generated by Michelle Obama. She never receives the email inviting her to escape to Africa, caught between her memes and unconverted to her “full Blackness,” an irony.

In the last two vignettes before Cooper’s exceptional, heartfelt conclusion, the first reveals a wealthy Black family who embrace white upper class mores, genociding their own identity to convince themselves they belong to the superior, fascist, master race (like a celebrity who recently praised Hitler). By internalizing white supremacist values, they don’t even realize they have destroyed their identity, their souls and their uniqueness. Furthermore, by adopting the”white” ethos as the proud bourgeois class, they have trampled all those who have shed blood to advance the hope of achieving civil rights, equal opportunity and justice by overcoming institutional racism. The bourgeois family don’t believe they are oppressed because they live by the “green.” The supremacists would never come for them because they have money.

We don’t realize how brainwashed they are until Black (the amazing Crystal Lucas-Perry) emerges from her prison underneath the mansion where their wealthy father has chained her for forty years. Finally free, Black confronts them in one of the most wild, convulsively humorous and hyperbolic rants about their blackness and the imperative to leave for Africa. They are so “white-fascist-think,” the truth she speaks is anathema. They kill her (typical Black on Black crime). The neighbors hearing “Black” screaming non bourgeois are infuriated about it. They call the police right at the precise moment Black has been genocided.

The scene is a powder keg of dynamite performances which are memorable and tragic because the family believes that they are a different identity via the “green” (money). It doesn’t matter if they stay or go. They have already lost everything valuable about what their culture means. Staying, they lose their lives. Cooper’s theme is clear. An oppressive fascist culture has as its most horrific tactic, get blacks to destroy the finest traits about them, their Blackness, by rejecting it and internalizing white tropes. Without that Blackness, they embody the worst of the fascist “master race.” They genocide their own and themselves.

Cooper also identifies the Black, female prison population in a very powerful scene. When freedom is posited, one of the prisoners, Blue (Crystal Lucas Perry transitions to a completely different mien and aura) hesitates to leave. In great fear and rage from all the abuse of her past, she creates a situation where she almost destroys her chances for freedom and is killed (or never makes the plane and is transmogrified). How Cooper ends this vignette and the last one when Peaches doesn’t make the flight to join those evacuating the US, are memorable scenes. They leave the audience in awe. The majesty of the actors’ performances and the stark language laden with substance and richness are stunning.

It is a supreme irony that though there is not one Caucasian in his play, Cooper’s themes and messages are particularly for those who have been blinded to believe that their skin color exempts them from white supremacy’s tyranny. It is only a matter of degree. Despotism impacts everyone in the culture as Cooper indicates in the last scene of the play.

In the end scene, the jet pulls away as the Blacks leave for Africa renouncing everything to go to a safe haven, while Peaches is left “holding the bag,” though it cannot be pulled up from the very place on which it rests, having become rooted to America. Cooper’s hyperbole may seem a farcical extreme. However, what they escape in the play we all faced because of the tyranny of the former president, who weaponized of a pandemic which killed a larger proportionate number of blacks and people of color. The blasphemous white supremacist tyranny the Blacks escape via his play’s metaphor, in reality, incited an undeclared war against U.S. democracy in a violent insurrection to thwart the peaceful transfer of power when Trump lost the election. Cooper’s understanding of the murderous intent of white supremacy is divinely inspired. He is a veritable Cassandra in his ability to read the ominous signs and incorporate them in this play. So the point that the only safe haven from such white tyranny is a return to Africa has been made palpable in the Ain’t No Mo, 2022.

The work is breathtaking in its themes, performances, writing and artistry. Don’t miss it. For tickets and times go to their website https://aintnomobway.com/ You will belly laugh and be moved at the same time.

T

‘Almost Famous’ The Broadway Musical Gives a Shimmering Nod to 1970s Rock ‘n’ Roll

From the response of the audience’s standing ovation and cheering, the snarky comparison by critics to the lead actors of Almost Famous and Dear Evan Hansen and other criticisms didn’t seem to matter. That is because Almost Famous delivers. This is especially so if one has seen the titular film (2000). If you appreciate a nod to what Howard Stern refers to as the best music of the past (better than the 1960s), and take that love or fandom to The Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, you will be happy you went to see this enjoyable production of Almost Famous directed by Jeremy Herrin.

Written by Cameron Crowe (book and lyrics), and Tom Kitt (music and lyrics), based on the Paramount Pictures and Columbia Pictures film written by Cameron Crowe, the show spreads its uplift and hope during a holiday season that is bringing crowds to Manhattan. Tourists, rockers and Broadway fans up for an entertaining night out will be pleased at the sterling voices, the humor, the energy of the performers and the music which connects the familiar story-line to the historical 70s music scene with nostalgia and poignance.

The classic rock covers (i.e. Deep Purple, the Allman Brothers), sustain us while Kitt’s original music is interesting with memorable songs like “Morocco,” “The Night Sky’s Got Nothing on You,” and “Everybody’s Coming Together.” The new melodies (a combination of rock and pop), convey the heart of the characters who are subtly drawn.

Fandom is the key to frequent successful film to stage transference. It may or may not apply here. The creators have taken a leap into the Broadway musical genre. They’ve created original songs for live performance and they have slipped in songs from the period (Led Zeppelin, Joni Mitchell, Cat Stevens, Lynard Skinner, Stevie Wonder, David Bowie and Elton John) into the musical’s action but not in the same way as in the film, whose background was replete with rock ‘n’ roll songs from start to finish. That doesn’t happen with this musical that has 18 newly-written songs. Included are four reprises from Tom Kitt (music) and Cameron Crowe (lyrics). The songs move the action as the characters express their conflicts, issues, desires and feelings and get tangled up in each others’ agendas.

Staged cleverly with Sarah O’Gleby’s movement, director Jeremy Herrin and the creative team eschew traditional choreography and keep the sets simple and minimalist to suit roadies on tour with the exception of William’s and Elaine’s home. This is in the service of suggesting the free form movement of the 1970s. The concept of great rock was fading into new musical trends like Rap then moved in the 1980s to MTV domination. Ultimately, the musical is a nod to 1970s rock ‘n’ roll and its ethos before commercialization and digital technology skewed it into something else.

Though the action is condensed with the added musical numbers, the arc of plot development, based on Crowe’s real-life journey as a teenage rock writer, follows the film. Wisely, the humorous lines in the production are lifted from Crowe’s writing, which won an Oscar for best original screenplay (2001).

One of the most important themes of the musical reveals an ambience of the 1970s, that was culturally strained between liberalism and conservatism. This is partly suggested by the opening number “1973,” when William Miller (the excellent Casey Likes), confesses to rock ‘n’ roll critic Lester Bangs (a manic, funny Rob Colletti). William sings about his conflicts with his mom. She stands in the way of his discovering “who he is.” In a state of flux, his mother Elaine (the humorous Anika Larsen), a teacher fearful of “drugs, sex and rock ‘n’ roll,”controls William and his sister Anita to the point where Anita (Emily Schultheis), rebels and leaves home.

However, Elaine can’t quite figure out who she is either. She adopts a healthy vegetarian/vegan lifestyle, clearly a liberal cultural influence. Yet, conservatively, she disagrees with subversive music (the rock ‘n’ roll Anita loves), and its cultural aftereffects (sex, drugs, wild partying). The pull of conservatism and liberalism is one William faces in his conflict with Elaine, but he’s leaning toward the underground and subversive, reinforced when his sister gives him all her rock ‘n’ roll albums to be “cool.” These inspire him to write for his school newspaper with the hope of a possible career as a writer or future music critic.

One element of his confusion, unbeknownst to him. is that his mother had him skip grades and lied about his age. Meanwhile, he is embarrassed because he has no pubes, is alone, uncool and alienated by classmates who humiliate him. Naturally, when he receives a response from Lester Bangs, the finest rock critic in Christendom, who accepts and encourages him, he jumps at the chance to write for Bangs’ Creem Magazine. On the road to being a bone fide critic, he lands an assignment from Rolling Stone to profile a rising band called Stillwater.

William manages to obtain Elaine’s permission by swearing he will remain pure and stay away from drugs and sex. Elaine relents because she dimly thinks it is better to connect with him and “keep him near,” (which fails), rather than lose him like she lost Anita. Ironically, she loses him in a different way. The rock band “kidnaps her son,” a funny and wonderful refrain in “Elaine’s Lecture” which is a lament that carries her angst about what is happening to William. He goes on the road with the band to get an interview, for which Ben Fong-Torres (Matthew C. Yee), will pay him handsomely. It’s an opportunity too good to pass up.

Likes’ William enjoys the excitement of “getting down” with beautiful young women who assist bands in their mission to be great. These groupies, cheering the praises of their leader Penny Lane (Solea Pfeiffer), have re-branded themselves as The Band-Aids. They are rock ‘n’ roll muses and their mission is “all about the music.” Indeed, Penny Lane has so fulfilled her role, that musicians have written 14 songs about her, and “all of them good,” affirms Estrella (Julia Cassandra).

With such a build-up of excitement Likes’ William is smitten with Penny (Solea Pfeiffer), and her Band-Aides who, along with Estrella, include Sapphire (Katie Ladner) and Polexia (Jana Djenne Jackson). Solea Pfeiffer is an “all that” Penny Lane who doesn’t quite convince us that she is about the music and so “cool” and scintillating to musicians, that she is their fount of inspiration. But then she is not supposed to. The Band-Aids, Penny and Stillwater’s Russel Hammond (Chris Wood), Jeff Bebe (wild, rocking Drew Gehling), Larry Fellows (Matt Bittner), and Silent Ed (Brandon Contreras) are “hype.” The actors (the Band-Aids and Stillwater), do a superb job of managing their characters’ “cool” with enough awkwardness for us to know that they are “almost famous,” but not there yet. And as a result, they will never really achieve super stardom because they get in each other’s way and are totally “uncool.”

The Band-Aides and Stillwater must walk the tightrope of not believing their own image to avoid falling into a destructive abyss which threatens throughout. This conflict and tension abates after the moment of truth on the airplane, especially when Woods’ Hammond and Gehling’s Jeff Bebe reveal their deepest secrets because they fear the plane will crash. This scene is technically delivered to surprising effect. Humorously, the tiny jet “flying” on a chord from one side of the stage to the other was so “over-the-top,” it worked in the service of farce.

The actors did a great job with the scene to convey just enough humor and fear to “spill the beans” and further wreck Stillwater’s “togetherness.” Believing their own hype brought them to facing this catastrophe on the plane. If they continued to take their humble tour bus, they would have been safer. The real dose of reality that Hammond says he wants is a pose only revealed when he thinks he’s going to die. Thanks to Derek McLane (scenic & video design), Natasha Katz (lighting design), Peter Hylenski (sound design), and the actors’ authenticity, the scene embodies their magical thinking vs. truth, a key conflict and theme of the musical.

Williams’ adventures initially captured in his journey through the songs, “Who Are You With?,” “Ramble On,” “Penny and William,” “Fever Dog,” and “Morocco,” evidence the pitfalls of being a rock ‘n’ roll critic who is always a “watcher” of the action, not a creator of it. Colletti’s Bangs humorously warns William to be “honest and unmerciful.” When William gets a taste of the band culture, its groupies and the challenge to be accepted, he tries not to be overwhelmed or lose his “objectivity.” Yet, he succumbs to their manipulations. First, there’s the rejection of him as a critic (called “The Enemy” by Stillwater’s Jeff Bebe). This wears him down and makes him want to “fit-in.” Though he resists and manipulates band members with flattery, he never adheres to Lester Bangs’s sage advice. Gradually, William is sucked in because Stillwater’s Bebe, Hammond and Penny Lane are good at “the game.” William is clever, but he’s a neophyte.

This “congenial” conflict between William, the band and Penny Lane disappears when he believes he is a friend, (“Something Real,” “No Friends,” the healing of divisions with “Tiny Dancer,” “Lost in New York City, Pt. 1” and “River/Lost in New York City Pt. 2”). But this “friendship” is a blind and his presumed love with Penny Lane eventually clarifies for him when she leaves him to the Band-Aids and joins Hammond (“It Ain’t Easy”). He is discouraged, but hangs on and writes a piece for Rolling Stone. However, it is rejected by fact-checker Allison (Emily Schultheis), and he is accused of writing a puff piece that Stillwater encouraged him to write. Only until Wood’s Hammond finally verifies William’s honest and “unmerciful” article to Rolling Stone, is the “magical fake world” of the band blown apart. However, this is beneficial for it allows the band and groupies to begin a new day.

Through lines in characterization are consistently effected. The conflict between son and mother abides from start to finish and provides much of the humor. Anika Larsen deftly balances Elaine as a typical loving parent, whose concern, knowledge and control are acceptable to the audience. She is never acerbic or preachy in the songs “He Knows Too Little (And I Know Too Much),” “Elaine’s Lecture,” and “Listen to Me.” Resolutions occur by the conclusion, when Anita has found herself and the full company sings the reprise of “Everybody’s Coming Together,” a rousing standout.

The actors, shepherded by Jeremy Herrin, do an excellent job of precluding who will end up on the floor of their own demise. This is strongest when we note the rifts between Bebe and Hammond, beginning when the T-shirts are distributed, then moving to the partial healing of their divisions on the bus with the singing of “Tiny Dancer,” another knockout scene and high-point at the conclusion of Act I. Though manager Dick Roswell (Gerard Canonico), has brought them together for a while, the conflicts among band members continue. They encompass Penny Lane and Russell’s relationship. Penny Lane is sold out in a bet that William witnesses during the Poker game scene. Pfeiffer’s Penny Lane and Likes’ William are excellent together with resonating lyricism and power when he saves her life after she overdoses on Quaaludes.

Most of the new songs work. Additional strong scenes/songs include Penny and William’s “The Real World,” Russell and Penny Lane’s “The Night-Time Sky’s Got Nothing on You” and “Something Real” when Woods’ Hammond falls apart at a fan’s house. At this point before the end of Act I, William attempts to keep Russell away from acid and fails. Woods and Likes do an excellent job revealing the negative pressure on their characters from the hype that Wood’s Hammond attempts to escape. It is an irony that he can’t because he is as needy and “uncool” as Penny Lane, Jeff Bebe and the others. However, he just hides it better.

Interestingly, in his immersion with the band, the only time they all come out of their “image” is when Likes’ blows it up with the final Rolling Stone piece about them, something that Wood’s Hammond encourages and has yearned for. Then, even Penny Lane is able to gain the strength to go to Morocco, leading to a satisfactory conclusion with “Fever Dog Bows,” which the entire company sings as a tribute to 1970s rock ‘n’ roll.

Kudos to the creative team already mentioned with special praise for Bryan Perri’s music supervision and direction, and Lorenzo Pisoni as physical movement coordinator. This is one to see for the shimmering performances, rousing music and nostalgia for a time we will never see again in its wacky innocence and silly “hedonism,” which seems quaint viewed through our current perspective. For tickets and times go to their website: https://almostfamousthemusical.com/

‘Walking With Ghosts,’ Gabriel Byrne’s Sonorous Solo Performance Resonates With Power and Intimacy

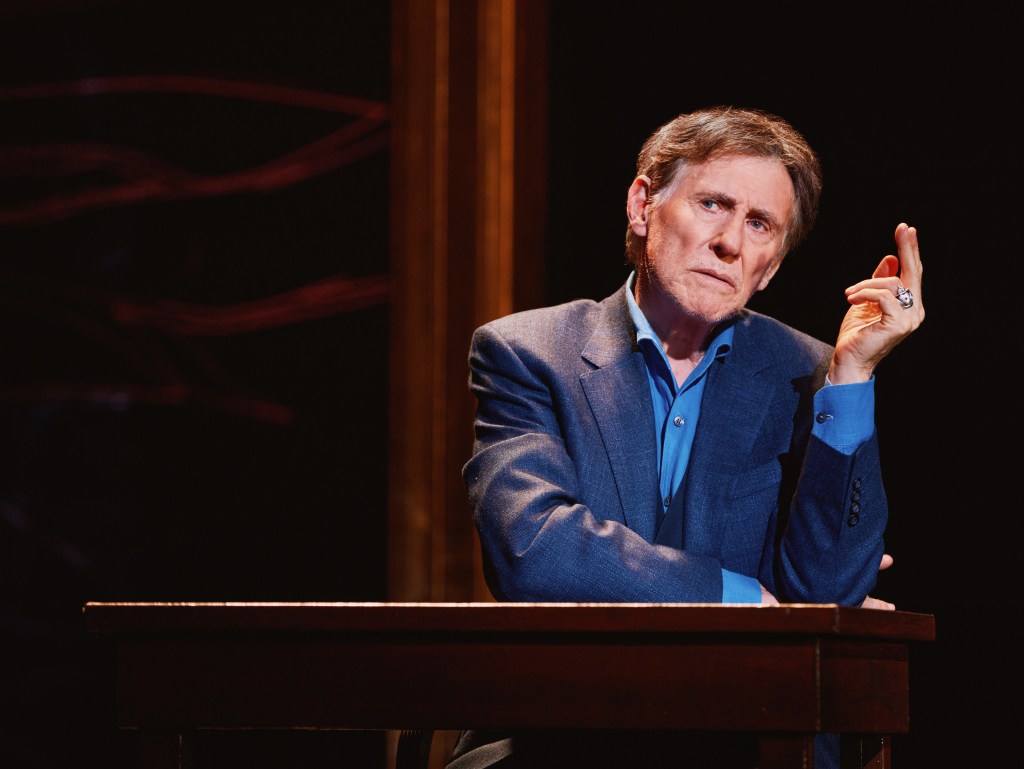

One way to reconcile being haunted by a past that is anchored to memories of people and places which have long disappeared, is to connect them to the present in the hearts and minds of those interested in their elucidation. Gabriel Byrne accomplishes this with his superb solo performance of his memoir Walking With Ghosts, adapted for the stage and directed by Lonny Price. The ghosts of Byrne’s past come to life through this humorous and poignant one-man show, currently at the Music Box Theater in a presentation that runs with one intermission.

In Walking With Ghosts Byrne captures the lyrical Irish rhythms of language as he touches upon the innocence, beauty, awkwardness, fear and grace in his childhood, growing up in Walkinstown, Dublin, Ireland before he left for the seminary in England at 11 years old to answer God’s call to be a priest. Through monologues, and evocative dialogue humorously peppered with the accents, voices and gestures of his parents, town characters, friends, a noxious teacher, even a brief encounter with writer Brendan Beehan, Byrne conveys the circumstances which contributed to forming his character and inspired him to expand his dramatic sensibilities.

These burgeoned into a globally renown career as a stage, film and TV actor as well as a film director, screenwriter and producer. Byrne has been twice nominated for a Tony award, has been nominated for Emmys and has won a Golden Globe and two Satellite Awards to name a few of the accolades he’s received for his work over the years. To understand the public, artistic Byrne, see his work and become acquainted with how he grapples with each genre, sometimes wearing a different hat than that of the actor.

To understand the private Byrne, Walking With Ghosts provides that portrait with illuminating, enjoyable glimpses into his childhood. He includes profound excavations that are personal and trenchant experiences which he relates as a forthright and raw expose coming “to know the world.” And as a coda to his successful career, which he leaps over and saves for another time (for there are no ghosts there), he recalls his parents’ humorous responses to his celebrity and ruefully admits to finally hearing their voices after they are gone.

In this third of his Broadway outings, Byrne showcases his remarkable talents. He appears onstage alone with minimal spectacle, directed lighting, spare props, and unadorned in the same clothing throughout. Indeed, Byrne is the transformative vehicle we focus upon, riveted with his immersive storytelling as both narrator and character, the elusive ghost boy, who has attempted to dodge and forget individuals in his past, but now stops and reflects about them lovingly, starkly for a few stirring hours with a ready, curious audience.

With lush, evocative descriptions and acutely crafted details, Byrne introduces his dreamscape and forages bravely into his past. He recalls his return to his vastly changed hometown overrun by development, where he feels like an intruder and claims himself “emigrant, immigrant and exile.” When he invites us in to receive his ghostly re-imaginings in haunted environs where ghost boy is running, we understand it is an incomplete and picaresque rendering. As in scripture, we see through a glass darkly without enough illumination and clarity to process everything. Yet what we see, hear and appreciate is from the depths of Byrne’s heart and private revelations bravely embodied so that we may identify and receive the gift he has humbly given to us.

Symbolically, the set design by Sinéad McKenna, features a back wall that is an artfully fractured mirror in need of repair, rather like a soul that has weathered the shocks and batterings evidenced by the damage but still holds together as one piece. McKenna’s lighting reflects a blur of colors and upturns Byrne’s shadow, so that it is an upside down pendant. It reminds one of the Tarot Card, the Hanged Man, which, in one interpretation indicates sacrifice and surrender.

Byrne’s remembrances structured in a fleeting chronology, like all memories, are vivid paintbrush images that strike then evanesce in humor and empathy. Other times his tellings sear into our minds, especially if we’ve experienced something similar. Throughout and together, Byrne’s recollections are a meditation on life that unfolds with beauty, synergy and power. To attempt to define one event or another as pivotal to his life remains an uncertain guess and requires thought. For all the memories he selects fashion who Byrne is from clearly apparent career profile and beyond to where the lines blur as son, brother, religious acolyte, amateur actor, friend and so much more. Thus, Byrne’s ghost boy leaps into characterizations and stories using themes and threads of ideas rather than a linear historical accounting.

Some recollections are unspooled in anectedotes and many of them land with humor. Enjoyable are his remembrances about his mother, i.e. her comments about his birth and his mystical naming received through an angelic visitation. Then there’s the soft, comforting recollection of his mother singing him a lullaby and his kneeling in prayer with his invisible guardian angel, who he knows stands near to protect him through the night. And there’s the memory of his father coming home from work as a cooper. Right afterward, he begs his father to ride on his knee playing “horsey, horsey,” his favorite game as father and son show affection for one another.

More acute, prickly memories move to the influence of the Catholic Church teachings and his first day of school when Byrne’s mother accompanies him and delivers him over to a formidable nun whose waxy hand he takes. Funny are his impressions of Christ on the cross, bleeding and naked except for a “nappy,” and his knowledge about heaven as he gives us his child’s take on the soul, limbo and the holy ghost as a pigeon. The latter prompts a sister to rebuke him, “It’s a dove not a common dirty pigeon off the street.”

And after recalling episodes of his days at school, the floodgates open and other aspects of the world enter. There’s his mother’s friend Mrs. Gordon, an iconic, crone-like figure, who enjoys frightening him so he wets the bed at night. And the joy of the thrilling Bicentennial Fair which is the epitome of a child’s play-land. He enjoins the exciting sights, sounds and feelings about the rides, candy, food and fireworks Irish-style, all of which Byrne relates in vivid technicolor.

The import of religion to his family is as palpable as open flame to flesh. From humorous quips about mortal sins to how Jesus could be in a wafer and where he goes when you swallow him, he discusses Holy Communion. We calculate his poignant revelation preparing for this sacred day. First his mother takes him to tea at the Shelbourne Hotel, then on to famous Clery’s for his outfit. We note the family’s struggle with finances and flinch when he is ashamed at his mother counting out the coins to pay the bills. Equally touching is Byrne’s description gorging on candy and sweets that he doesn’t have very often and that he buys from his Holy Communion donations. He becomes so sick he soils his expensive outfit and hides in the bushes for hours fearful his mother with be angry with him. When she finds him, he discovers she loves and soothes him despite ruining what costs so much, an item that means so much, but they can’t really afford.

Byrne’s humor and enthusiasm extends to a meditation on his beloved grandmother who took him to the “pictures” and inspired a love of film. His description of a brutal and abusive teacher in his elementary school is only ameliorated when students get revenge then stick together and don’t confess, despite the pressure to do so. These and other events amass the ghosts that walk with Byrne in his childhood that fade. However, there is one ghost that haunts him for much of his life.

Enchanted by the idea that God might be calling him to be a priest, he goes to England to the seminary where he is happy. Enjoying being in England and getting away from home, he believes he has found a place of refuge. He is not hit or humiliated by the other kids as he was in Ireland. Also, he plays football and he makes easy friends. However, this changes on a dime. Byrne’s description of how the priest who favors him, gives him wine to drink, and absolves him of any impure thoughts he might have uses these sly techniques to insinuate and initiate a predatory sexual attack. The dialogue is pointed as Byrne assumes the accent and soothing demeanor of the priest. The event is so clearly disclosed and so classic of sexual predators, we shouldn’t be surprised. However, we are shocked and horrified. Byrne’s expose of the Catholic Church and the priest reveals the turning point in his life. The glorious faith that his parents believed in and lovingly shared with him in hope, his naming brought by an angelic visitation, his innocence and his desire to be holy is devastated and destroyed.

Years later after he’s found himself, Byrne shares that he located the priest via the internet and calls him, perhaps searching within to forgive the priest and forgive himself. On the phone he can’t bring himself to tell the elderly retiree with a poor memory in a retirement home that he wishes hell on him. In a confused daze, the priest thanks him for calling. He hangs up; empathy overtakes him. Throughout the the rest of the play, it is clear that this event contributed to Byrne’s choices after he left the seminary. He expresses the incident so vividly, it is indelible, irrevocable. That is the keen point Byrne makes through understatement without ranting or passion.

What happened to him happened throughout the global Catholic Church then and most probably is still happening today. However, if one doesn’t understand faith, religion and the power of a culture and family that holds God dear to them and has for centuries, the ghostly impact of this priest on Byrne’s life will be completely lost or misunderstood. As a reverential dramatic moment, the scene is incredibly rendered by Byrne. We sense that this raw incident he expresses not only for himself, but for every other person who has been sexually abused by a cleric whether Catholic, protestant, New Age, Hindi, etc.

In Act II we understand how the events in the seminary emotionally jack knife and send Byrne wandering away from his association with the Catholic Church to atheism. After he returns home from the seminary (Does he tell his parents what happened?), a series of unenlightened jobs that worsen (plumber, dishwasher, toilet attendant), keep him foundering until eventually, his friend suggests he join a non professional repertory company of actors. They are so welcoming, it is then he finally feels he belongs and is at home. As he outlines how he does various parts with his actor friends, a lively take on how each of his colleagues takes their bows is smashing. It is one of the more exuberant stagings by Price that segues into Byrne’s career moving off to the Focus Theatre and sojourns into professional acting and subsequent humorous disasters until he begins to support himself.

The second act has two other significant reverential moments recalled by Byrne. His sister Marian who he was close to pursues an acting career in London. However, though no one can explain how, she ends up in a mental asylum and they call Byrne to pick her up and take her home. What he describes, we’ve seen in films and we shouldn’t be surprised. Yet, his recollections are vivid and disturbing. Again, we are shocked by his incredible rendering of the asylum and the treatments she receives to “make her well” but which don’t. Byrne’s metaphor for her, “a wildflower in a crumbling wall,” expresses the culture that has caught her, but one in which she still provides beauty. However, the stigmatized by her mental illness, that beauty is not recognized. Thus, we empathize with his emotional response when he receives a call that she has died unexpectedly. She’s in her early thirties. She is one more ghost who haunts him.

Byrne’s episode with Richard Burton is not only fascinating, it, too, is heart-breaking. Drinking is a part of the culture in Ireland as it is in Wales where Richard Burton became addicted. It also is embedded in the culture of the entertainment industry which is a destroyer of artists. Byrne shares the time in Venice when he and Burton are working together and become drinking buddies. The occasion segues to Byrne’s recognition that he’s an alcoholic and must seek help which he does relaying he’s 24 years sober. He reminds us and himself that he has made it out of that hell, whereas Burton died with alcohol crystals coating his spine at his death. Once again Byrne’s understatement and lively reminiscences are the tip of the iceberg. Below are the miserable trials, the pain of alcoholism, the hangovers, the physical and emotional devastation and looming death. But this doesn’t need to be spoken and Byrne is not preachy, just thankful. The warning to others is clear. It’s possible to come out of it, if you get help.

A quick note about Sinéad Diskin’s music and sound which floats in and out unobtrusively. Like the structure of Walking With Ghosts, it is thematic and threaded, conveying the elusive emotions that substantiate Byrne’s episodic meditations. With the prosceniums frames that sometimes are gold other times red, etc., the mirror effect is enhanced as they appear in perspective to diminish in the distance suggesting the motif of fading away and evanescence. Such is the nature of memory that erupts and disappears unless one keeps it alive in another repository which Byrne does evoking their ghostly presence each night on stage. He identifies our part in this process or reconciliation in his final statement. The ghosts he was walking with are in him. He is no longer running. He has made peace with himself and them.

This must-see production is a heartfelt encomium to Byrne’s past spoken with the lilt of poetic feeling that is never overdone, but is as light as mists that burn off in daylight. For tickets and times go to their website: https://gabrielbyrneonbroadway.com/

‘Leopoldstadt,’ Tom Stoppard’s Brilliant Chronicle of Family Holds a Trenchant Warning

In five acts spanning the years from 1899 through 1955, Tom Stoppard focuses on a wealthy, Jewish, Viennese family as they navigate the turbulent waters of social and cultural transformation in Leopoldstadt. Stoppard’s latest play begins at the turn of the century and moves through two World Wars. In it the playwright heightens the most salient themes about antisemitism, social responsibility, discrimination, human rights, family, ancestry and ever-changing political power structures which promote tribalism.

Stoppard weaves these concepts into the story of the multi-generational Merz and Jakobovicz families. With a panoramic view, Stoppard shadows their journey forward and backward as Jews, who attempt to maintain their identity and place in the culture and society of Vienna, Austria. Stoppard’s masterwork which first premiered in London, is currently in its Broadway run at the Longacre Theatre, coming in at 2 hours, 10 minutes with no intermission. Leopoldstadt, directed by Patrick Marber, is one of Stoppard’s finest works.

When we meet the members of the two families in the large Merz drawing room as they celebrate Christmas 1899, Hermann Merz (David Krumholtz) affirms that they can be grateful for Emperor Franz-Joseph’s new freedoms. For over fifty years as Jews, they have said goodbye to “wearing a yellow patch and stepping off the pavement to make way for an Austrian.” They must only withstand discrimination “now and then.” Wealthy textile manufacturer Hermann, baptized a Christian, has married the elegant and lovely blonde-haired Gretl (Faye Castelow), who is having her likeness painted by the foremost artist of the Vienna Succession, Gustav Klimt.

During the conversations we note the prosperity and culture of these two families, who inhabit the same social circles as the foremost professionals and artists in Viennese society. They name-drop Mahler, Schoenberg, Schnitzler and Freud. Hermann affirms his evolution as a Jew. “My grandfather wore a caftan, my father went to the opera and wore a top hat, and I have the singers to dinner-actors, writers, musicians.” Professor Ludwig Jakobovicz (Brandon Uranowitz) is a patient of Sigmund Freud and interested in his own dreams. Ludwig shows his theoretical mathematical prowess by questioning Hermann and Gretl’s son Jacob about Riemann sums. Doctor Ernst Jakobovicz (Aaron Neil) is meeting the lecturers for a Christmas drink. This is protocol, for he is a Christian.

To emphasize his full embrace of the cultured Vienna as the Promised Land, Hermann repudiates any interest as a Jew in Theodore Herzl’s Zionist idea of a liberal state in Palestine. Ludwig agrees that no one would want to go to the desert, certainly not the Jews who are part of Austrian bourgeois high society. Obviously, Hermann is not prejudiced. He practices the dictum that Jews in business should to be opened-minded to all cultures and religions to expand their opportunities, if they are to succeed. We discover later in the play, that success is paramount in Hermann’s life. With forward momentum, Hermann’s wealth and cultural aspirations have been bolstered by his marriage to his Christian wife Gretl. He is the first Christian of Jewish descent in the family.

However, Grandma Emilia (Betsy Aidem) reminds Hermann of the cost of his sacrifice for his children to be Christian. He has thrown over what he should have valued most, family and ancestry. But it’s no matter. Attitudes toward Jews have shifted. Grandma Emilia points out that once “hated as Christ-killers, Jews are now hated for being Jews.” Illustrating how much Hermann has changed for the sake of his career, Ludwig supports her comment with the terrible reality: he will always be a Jew. Grandma and Ludwig toast to a future territory for Jews, where they might be safe. That their wish comes true after the horrific Holocaust and murder of millions gives us chilling pause. However, safety, even in modern Israel, is elusive.

In this first act Stoppard has laid out the ground rules, intimating how the principle theme, “it can happen here and it can happen again,” will come to resonate as an irrevocable truth. As a family member states toward the play’s end, “barbarism can’t be eradicated by culture.” Indeed, the rational is often supplanted by the irrational. In the subsequent acts we understand how this becomes a reality for the two Jewish families in the play. They ignore the burgeoning antisemitism in Vienna. Ineffectively, they attempt to navigate around it by sticking together and celebrating tradition, until it is too late to leave.

In Act 2 (1900) Stoppard unspools his themes to reveal that the discrimination that Hermann refers to runs deeper than “now and then.” Fritz (Arty Froushan), an Austrian dragoon, eschews the younger Jewess Hanna and falls in love with the older Gretl, Hermann’s wife. They carry on an affair for a time, until she tells him she must break it off because Klimt’s painting of her will be finished, and she will be recognized sneaking around with him. When Fritz boasts about his affair making a Jewish slur in the company of gentlemen and in Hermann’s presence, Hermann initially doesn’t realize Gretl is Fritz’ lover. He thinks Fritz is insulting Gretl and attempts to recover their honor by proposing a duel. Refusing to engage Hermann because he is a Jew, Fritz insults him further by telling him his military status forbids him dueling with Jews.

Humiliated and doubly stripped of his honor, Hermann must bow to Friz, whose antisemitism holds sway. This prejudice is a warning that Hermann will always be an inferior in a culture that despises his heritage. Though Fritz’s rejection saves Hermann’s life, Hermann is gravely affronted and embittered because he doesn’t consider himself a Jew. However, Hermann later exploits the situation to his and his family’s advantage, after he realizes that Gretl and Fritz have had an affair. Ironically, being identified as a Jew upsets Hermann more than his wife’s infidelity. From this moment afterward, the situation worsens for Viennese Jews and members of these two families.

In subsequent acts we see the families experiencing events with less emphasis on the culture, as they uplift the Jewish traditions to humorous effect because they are not religious. For example, Stoppard has them confuse the banker Otto with the Mohel who is late to Nathan’s brit milah, as Sally runs to and fro conflicted about her son’s painful circumcision. She is not mindful about the symbolism of the circumcision, which means he is bound to God. Instead, she wants him to “be like his father,” following tradition. Interestingly, her decision is fateful. Stoppard intimates the importance of his being bound to God at the conclusion of the play.