Category Archives: Broadway

Martin McDonagh’s ‘Hangmen,’ Theater Review

The year 1965 signifies a momentous occasion. By 204 votes to 104, The Murder Act has abolished hanging and the death penalty for those convicted of murder in Great Britain. For human rights advocates and those agreeing that capital punishment isn’t a deterrent, thus, civilized countries shouldn’t practice tribal law, there is rejoicing. For hangmen across the UK, there is less enthusiasm. Martin McDonagh’s sardonic, brutal, unapologetic and macabre humor works brilliantly in his dark comedy Hangmen about some hangmen which centers around the end of hanging in the UK. Hangmen which won McDonagh the 2016 Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Play, begins with an official hanging and ends two years later after the death penalty has been abolished.

Currently on Broadway at the Golden Theatre, in Hangmen McDonagh centrifuges the wicked human impulses of irrationality, arrogance, machismo and the mechanical banality of evil, then sends these elements into the stratosphere of random circumstance. Add to that mischance, misadventure and mishap, an ironic and inevitably surprising McDonagh-style conclusion is seamlessly effected in this engaging, comedic work. One finds the events mysterious, grisly and lurid until one allows the belly laughs to erupt and the smiles to pop up on one’s face at the systematic take down of males, their grotesque appreciation of insult humor, barbarism and their dung-heap grossness which females are sometimes a party to.

How McDonagh maintains the balancing act of the humorous with the gruesome, effectively weaving the tonal grace to bring on laughter through organic characterizations, always astounds. He accomplished this in the uproarious A Behanding in Spokane (2010) on Broadway (starring Christopher Walken and Sam Rockwell), and in his other works, with the selection of exceptional actors who understand not to “force the laughs” but just to slide into inhabiting the beings that are incredibly loathsome under other circumstances. In the McDonagh settings and arc of developments, what unfolds is the revelation of humanity in all its inglorious ungraciousness. McDonagh’s humans suffer and joke about it, not attempting to evolve or better their soul wretchedness. They just wallow and lay about. In that there is the humor.

This especially applies for the characters and situations in Hangmen, whose chief irony is that the national acceptance of brutality in destroying human life as a punishment for destroying human life (a mild form of genocide), has ended. But the state of human nature which is tribal and hideously, wickedly murderous continues. It’s the same old, same old. And perhaps with capital punishment abolished, it is indeed worse.

McDonagh investigates various themes about “the company of men,” the willful deceit of human nature and its impish cruelty and brutality, and other themes in the Hangmen, whose focus lands on Harry, the hangman (the wonderful David Threlfall). Harry owns a pub in the north of England and entertains as the king of his space the usual locals who come in for more than a pint. These wayward alcoholics, which he obliges and indulges, include Bill (Richard Hollis), Charlie (Ryan Pope), and the near deaf Arthur (the hysterical John Horton). Occasionally, Inspector Fry (Jeremy Crutchley), drops in, adds his wisdom to the comments of the tipsy crowd, who fall into a natural banter as the alcohol buzz takes over their minds.

On the sterling occasion (for potential murderers in the UK), of the passage of The Murder Act, reporter Clegg (Owen Campbell), comes to the pub to interview Harry about his past glories as a hangman, which initially Harry refuses, then agrees to out of earshot of his clientele. Others who drop in and exacerbate the events which gyrate out of control in Act II are Syd (Ryan Pope), Harry’s former colleague that Harry fired for exclaiming about a male corpse’s lifted genetalia and other inappropriate mistakes. Additionally, there is Harry’s wife Alice (Tracie Bennett), and his teenage daughter Shirley (Gaby French).

Alice who helps in the pub puts up with Harry and the others and encourages her husband, who she is proud of in a mindless kind of thoughtlessness. But it is obvious that Shirley, who receives the brunt of her parents negative comments because of the age gap and her mopey disposition, is chaffing at the bit to have some adventures. If only someone would give her the opportunity.

The opportunity arises when a rather mysterious, menacing bloke from the south comes into the pub, has a few pints then inquires about lodging. Mooney (Alfie Allen), is the catalyst who propels the action along with Syd, whose deviousness and impulse for revenge sets in motion the sequence of events from which there is no turning. The events are inexorable, especially since Harry’s rival and fellow hangmen Albert (Peter Bradbury when I saw the production), shows up in a coincidental irony and adds to the final debacle.

There is no spoiler alert because so much of the fun of this play is in the twisting plot, incorrect assumptions that McDonagh whimsically leads you to make, and overall uncertainty about which characters are truly malevolent and which ones are actually fronting evil but are almost nice and kind. Beneath this foray into the darkness of human nature, the elements are profound and frightening as the scripture does say that wickedness lurks in the human heart. Naturally, in the culture’s global lexicon, the heart is tender and sweet. Not for McDonagh in the Hangmen, in this entertaining look at machismo, revenge, female complicity, arrogance, pride, lawlessness and fronting.

If you enjoy McDonagh and are wanting a laugh or two or many, this is one to see for its wit, cleverness and sardonic finger-pointing at who you really are in your soul. Threlfall’s portrayal of the fascinating character Harry and the solid cast performances shine a light on McDonagh’s themes about human nature. Ironically, in this current time, these themes seem to resonate roundly with Vladimir Putin’s current expose of the misery of his own soul and a want of humor and laughter. Thankfully, McDonagh reminds us of ourselves with brilliant humor which might makes us want to be different for an occasional minute or two.

Directed by Matthew Dunster, who collaborated with Anna Fleischle (scenic and costume designer), about the intriguing two level sets that are quite elaborate with spectacle yet functionality (a cafe, a prison, a darkly paneled, expansive pub), the play succeeds on many levels (sorry, I couldn’t resist). Perhaps there’s a bit of symbolism to think about as you get to watch the pub set rise from hell (as it was referred to in Elizabethan times-the space under the proscenium), as the prison and place where poor Hennessy-whether guilty or innocent was hanged- slowly moves to the second level atop the pub. Thus, the pub becomes the set on the main stage and the prison cell and cafe are above it.

Finally, kudos goes to Joshua Carr’s lighting design and Ian Dickinson for Autograph in sound design.

For tickets and times go to their website: https://hangmenbroadway.com/

‘MJ’ is One of the Greatest Broadway Productions Ever

For much of Michael Jackson’s life, there was controversy. Extraordinary genius is not often reverenced by those who attempt to control it, exploit it or covet it as theirs. Sometimes it is least understood by the person who possesses such talent, until it is too late, and there are only a few years left to try to get it all down.

One-of-a-kind greatness is as ineffable and mighty as what we imagine divinity is. But divinity streams in a multitude of directions. In spirit and light it is incapable of being contained. A bit of that was Michael Jackson’s talent, genius, divinity that he emblazoned on our planet for too brief a time. It is a bit of that Michael Jackson which Myles Frost so lovingly portrays with precision, excellence and prodigious beauty in MJ, with the book by the sterling Lynn Nottage that currently runs on Broadway at the Neil Simon Theatre. This production is an unforgettable, blinding amazement, full of wonder.

Unlike other shows that have been dubbed jukebox musicals, MJ cannot be categorized as such and defies pat, convenient labels. First, though Michael Jackson’s music is featured throughout, the music threads who he is albeit “through a glass darkly,” if we can ever know another individual. The production soars because, as Myles’ MJ tells MTV documentarian Rachel (Whitney Bashor), if we “listen” to his music, it “answers questions” we might have. Thus, if we really intend to know who Michael Jackson is, we must examine his music. MJ does this by presenting riffs of his treasured, award-winning songs in two acts, though not in completeness because the breadth of his work would require days to display in full.

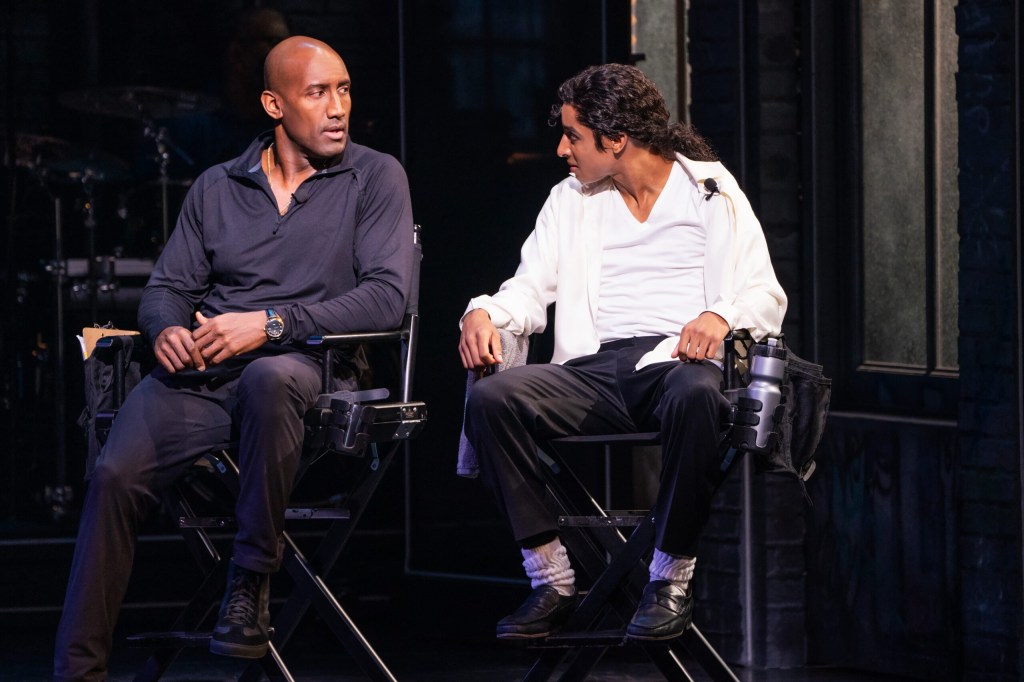

Wisely, Nottage focuses on a period in Michael’s life which manifests a turning point right before he travels globally on his Dangerous tour. It is 1992 in a L.A. rehearsal studio. Through flashback and flashing forward, framed by the present in the studio, Nottage provides richness and depth, crystallizing vital themes and conflicts MJ confronted externally and internally. These include: 1) the media’s rapacious hunger to exploit scandal and create MJ’s twisted identity that it hypocritically blamed him for; 2)his struggles with his father in going solo and breaking from his family to obtain his own autonomy as a person and artist; 3)his struggles to evolve his music beyond his industry producers and labels represented by his father Joseph (Antoine L. Smith), Berry Gordy (Ramone Nelson), and Quincy Jones (Apollo Levine).

Additionally, Nottage examines his work ethic and quest to be perfect, a recurrent theme in MJ. For example after rehearsing various numbers for the Dangerous tour to the breaking point, MJ asks, “But is it perfect?” It is a refrain he’s internalized from his childhood when his father pushed the Jackson 5 to the brink and didn’t allow them to “be children.” Finally, MJ is representational as a black every man striving against the color bar everywhere. Thus, we see his father, his family and his life struggles against institutional racism in the music industry and culture.

Complexly encapsulated throughout, Nottage reveals his personal struggles to manifest love, and overthrow the cruel abuse he received as a child, teen and adult (in the media and entertainment industry). He must do this to spread the love in his music and not transfer the culture’s hatred which is so easy to internalize. This is most probably the most difficult ask of himself that Michael pushes himself toward. This is the thing which is impossible, not the incredible nature of his tours or finding the money his financial manager Dave (Joey Sorge), requires, using his Neverland Ranch as collateral to fund the Dangerous tour. Importantly, Nottage notes his personal struggle to understand and forgive himself reflected in the incredible performance of “Man in the Mirror.” However, does he achieve self-love finally, the bane of all human existence? Ah, well…

Interwoven to spotlight these themes and conflicts is Michael Jackson’s fabulous music featured with the dancers in later songs during the rehearsal period for the Dangerous tour and in memory vignettes. Also, we enjoy featured songs in MJ’s discussion of his work with Rachel which includes numbers from his albums Off the Wall and Thriller.

From his childhood Little Michael’s ( the superbly talented Walter Russell and Christian Wilson alternate) incredible voice shines with his brothers portrayed by performers who also take on different roles. In the segments when Myles’ MJ in the present reflects about correlating events in his childhood, we note his father’s gruff, abusive prodding as a taskmaster (portrayed by Antoine L. Smith the night I saw the production). And we appreciate his loving mother’s comfort as a counterbalance who MJ relies on. Katherine Jackson’s incredible voice is poignant and lovely as she sings with Little Michael, i.e. “I’ll Be There.” When MJ comes back from his thoughts about the past, answering questions from the documentarian at times and other times just letting memories emerge, Myles as the adult MJ sings with Little Michael and they encapsulate the convergence of the past with the present. Perhaps this is a healing, self-revelatory moment.

Likewise, the same occurs with teenage Michael, portrayed by Tavon Olds-Sample as Nottage explores the height of the Jackson’s fame with their appearance on Soul Train performing “Dancing Machine.” Especially when MJ steps back into the past, songs in the vignettes explore his emotions at the time. Then MJ comes back to the present into the rehearsal studio where the dancers are singing the same number. The past turmoil is concurrent with the turmoil he goes through in the present with his managers and directors telling him what he wants isn’t possible. It is a refrain he received his entire life and must overcome continually. The transitions from flashback to forward present are beautifully effective as rendered in songs.

Wisely, the structure and organization of MJ is complexly framed by the present and is driven by a confluence of emotional and personal issues which erupt throughout the production. These issues, Nottage intimates were the ones to spiral out of control later in Jackson’s life. The issues explored in flashbacks reveal that MJ is a fluid memory piece and musical. It is as if Jackson, given over to his own talent and unconscious, becomes haunted by the past which intrudes upon the present to generate the direction of his art and personal life. It is that past from which “he runs” (a superficial assessment by the media). Regardless, it is that chaos and emotional angst from the past which infuses and creates the greatness of his being and work, Nottage suggests throughout. It is even reflected in the words of Barry Gordy who claims that Little Michael sings with the pain of an adult’s experience.

Though I wasn’t a Michael Jackson fan, after seeing MJ, I have become one, learning of some the facets of his talent and genius which he attempted to perfect and which anyone who looks deeper into his life with understanding recognizes what he accomplished as one of the most significant global cultural icons of the twentieth century. Importantly, MJ is a celebration of Michael Jackson’s goodness, graciousness, gentleness and love, revealed in his spectacular ability to compose, sing, dance, produce and innovate new music styles and initiate forward trends in all these listed, including fashion.

MJ is also a memorial to Michael Jackson’s work given that through great pain comes art which is timeless. Though some would quibble that “his” type of music isn’t art, Nottage’s book and this production rises above that inanity in its affirmation that what Michael Jackson accomplished must be reviewed seriously apart from scurrilous tabloid journalism or even an attempt at documentary. Though he was Known as the “King of Pop,” the Broadway production reveals that “handle” was a superficial, limiting meme.

He was a phenomenon that we will not see again, a sensitive maverick “music man” who morphed into mythic beings and as easily shapeshifted out of them into new personas. As he evolved, he swiftly left history and the media in the dust, something which the media appears to refuse to understand. One has only to view his vast body of awards and global recognition, his millions of record sales the dollar amounts, the presidential awards, global awards, the breaking of 39 Guinness World records to begin to “get this.” Indeed, he is the most awarded individual music artist in history.

MJ the Musical begins in an L.A. rehearsal studio in 1992 as dancers and the soft-spoken Michael (the shining Myles Frost) suggests ways to improve “Beat It,” the number the dancers work on. Sequestered in a corner, a two-person MTV documentary film crew records until the overexcited camera man, Alejandro (Gabriel Ruiz), loses his cool in the presence of this living myth and MJ “yells” about the how and why of cameras in the studio. Rachel (Whitney Bashor) steps in and saves the day assuring Rob (Antoine L. Smith) and Michael they are “unobtrusively” there to record MJ’s process of putting together his Dangerous World Tour. Frost’s Jackson quietly explains that the tour to promote his album Dangerous will travel four continents excluding the U.S. and Canada in the hope of raising $100 million for his newly established charity Heal the World Foundation to help children and the environment.

Immediately, the strains and pressures of conflict between the media’s mission to raise dirt, versus the sensitive artist and the private individual who yearn to be understood are manifest. Behind MJ’s back Rachel affirms to Alejandro that she wants to delve into his personal struggles, blowing by his art. It is the reason why they insinuated themselves into the rehearsal studios with the guise of filming his tour preparations. Once again, MJ is trusting and allows her to stay to publicize the tour.

Intriguingly, Nottage points out that the documentarian attempts cinema veritae. However, by the end of MJ we see this is a blind. Rachel gets “what she wants.” She has overheard a conversation by MJ’s close associates Rob (Antoine L. Smith) and Nick (Ramone Nelson) about his taking too many painkillers because of the accident filming a Pepsi commercial. Instead of concentrating on his music, though she says she will be fair, we understand “fair” means not necessarily giving MJ the benefit of the doubt. It is “The Price of Fame” that he learns from his father and without which he couldn’t perform. Regardless, it is a cul de sac in which “You Can’t Win,” sung by Berry Gordy (Ramone Nelson) and teenage Michael (Tavon Olds-Sample).

By the conclusion of MJ, we discover that “facts,” too can be twisted into untruths, and what is called for and never pursued by the media is understanding and empathy. Thus, as a theme media exploitation manifests three minutes into MJ, revealing what dogged him and grew to an insanity by the end of his life. The media’s rapacious commercialism to get “the exclusive” scandal to tear down the myth it grudgingly helped to create is integral to MJ. The constant struggle with the media later strengthened him to transcend every barrier institutional racism put up to thwart him in exploitative cruelty that Jackson later excoriated and exposed, using his songs as a weapon to beat back injustice, planet devastation, global child trafficking and more.

In a perfect meld of music and dance numbers, Nottage’s book is the skeleton upon which the creative team of Jason Michael Webb (music direction, orchestrations, arrangements), David Holcenberg (music supervision, orchestrations, arrangements), and Christopher Wheeldon (director, choreographer) sculpt the greatness of Michael Jackson’s artistry in his humanity. Songs represented are from all of his albums; in alphabetical order they include (ABC, Bad, Beat it, Billie Jean, Black or White, Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough, Keep the Faith, Rock With You, Smooth Criminal, The Way You Make Me Feel, Wanna Be Startin’ Something) to name only a few. With Thriller (look at how his father in costume moves off stage into the nightmare world which emerges from his imagination) how the song is incorporated with his living, awake nightmares in his own life at this point in time is just fantastic.

The set design (Derek McLane) exemplifies MJ’s inner and outer conflicts magnificently, in vibrant colors for the dynamic award winning numbers. They even get the opening propulsion up from the trap under the stage for a huge WOW! It signifies MJ successfully got his crew to do this for his Dangerous tour. See the production MJ for this rush of excitement, and explosive fun surprise. Or look it up on YouTube if you are not coming to NYC.

For the “smaller” intimate moments in the Jackson family home, the design is simpler, but functional and appropriate to the time. The retro look continued for the Soul Train vignette is heartwarming as the introductory music opens, reminding us of our youth and the time in the nation where black entertainers like Michael rarely crossed over. They had to appear on Soul Train for publicity. The lighting (Natasha Katz), complementing the set design for the maximum striking “fantastical,” especially with the “Thriller” number that just kills it are all other-worldly, as Paul Tazewell’s costumes provide the fearful/graveyard monster touch. The costumes of course are so varied, but all are MJ. Importantly, Gareth Owen’s sound design is spot on so the lyrics are clear, the music strongly wonderful.

Peter Negrini’s production design, Charles LaPointe’s wig and hair design, Joe Dulude II’s make-up design all thrust the actors and especially Myles Frost into glory and provide the unity of spectacle this production so fabulously renders. Enough cannot be said about Myles Frost’s portrayal that is emotionally devastating because he is Michael Jackson’s beating heart and so gratefully appreciated for his amazing talents and will to become MJ for each of the nights of the week. Shepherded by Christopher Wheeldon’s masterful direction and thrilling, hot choreography, they are MJ‘s lifeblood along with the cast who entertain us to their last nerve. All are nonpareil.

We see that in the songs in his later life, MJ attempts to overthrow the forces that exemplify the worst manifestations of greed, pernicious exploitation, hypocrisy, falsehood and hatred in the culture and in his personal life. What he went through first with the media which built him up to destroy him, we have witnessed these past years in the propaganda used to destroy in the service of furthering others’ hidden agendas, regardless of the facts in this heightened time of political power plays.

As the last individual walks away from the Neil Simon Theatre, after seeing MJ, they should leave with the knowledge that what Michael Jackson represented to fans, foes, colleagues and those nearest and dearest to him is incalculable. Whether one scorned, predatorized, idolized, exploited, manipulated, in short any action word you might use to exemplify how people related to him, Michael Jackson impacted all of us through his music, his humanity and his tragedy. Lynn Nottage, the actors and the creative team have done a sensational and dazzling job of assisting Myles Frost in bringing the legend to life.

Finally, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things. With regard to Michael Jackson and the production’s greatness, this scripture seems appropriate to leave you with.

For tickets and times go to the MJ website: https://mjthemusical.com/

Mary Louise Parker, David Morse Renegotiate Their Roles in the always amazing ‘How I Learned to Drive’

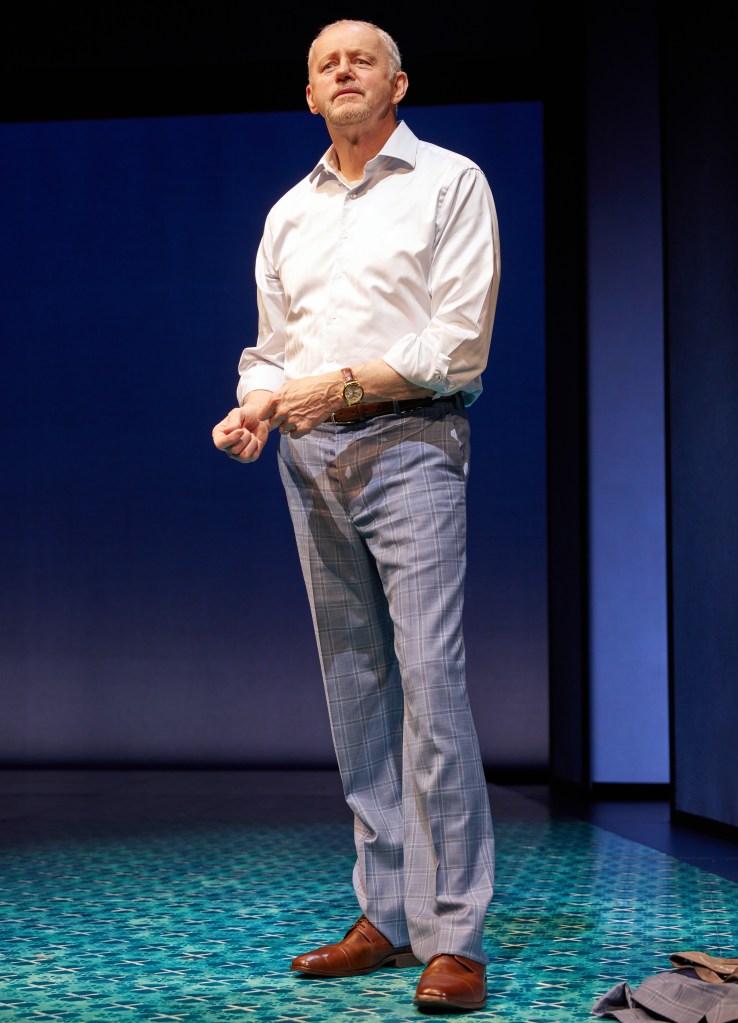

Paula Vogel’s Pulitizer Prize winning How I Learned to Drive in revival at the Samuel Friedman Theater is a stunning reminder of how far we’ve come as a society and how much we’ve remained in the status quo when it comes to our social, psychological, sexual and emotional health, regarding straight male-female relationships. Pedophilia and incest by proxy are as common as history and not surprising in and of themselves. On the other hand how particular male and female victims lure each other into illicit sexual self-devastation is unique and horrifically fascinating.

This is especially so as leads Mary-Louise Parker, David Morse, and director Mark Brokaw put their incredible imprint on Vogel’s trenchant and timeless play. Interestingly, Parker and Morse are reprising their roles from the original off-Broadway production, with original director Mark Brokaw shepherding the Manhattan Theatre Club presentation. Parker (Li’l Bit) and Morse (Uncle Peck) are mesmerizing as they portray characters who manipulate, circle and symbolically search each other out for affection, love and connection. The relationship the actors beautifully, authentically establish between the characters is heartbreaking and doomed because it cannot come out from under the umbrella of the culture’s changing social mores, Peck’s psychological illness from the war, and Li’l Bit’s familial, sexual psychoses.

How I Learned to Drive reveals what happens to two individuals (a teen girl and an adult male), who engage in the dance of psycho-sexual destruction while negotiating feelings of desire, love, attraction, fear and guilt under society’s and family’s repressive sexual folkways and double standards. What makes the play so intriguing is not only Vogel’s dynamic and empathetic characterizations, it is her unspooling of the story of the key sexual-emotional relationship between Li’l Bit and Peck.

Li’l Bit and Peck’s relationship is not easily defined or described as sexually abusive, though in a court of law, that is what it is, if an excellent prosecutor makes that case in a blue state. However, in a red state, it might be viewed differently. Consider 13 states in the US allow marriage under 18, and Tennessee has recent records of marriages of girls at 10 years-old with parental or judicial agreement.

Sexual abuse, if the players are amenable and influencing each other for reasons they themselves don’t understand, is a slippery slope depending upon the state’s political and social folkways, the familial mores and the perspectives of the players themselves. Ironically and eventually, a turning point comes IF the abuse is recognized and the relationship ends whether exposed to the light of public scrutiny or not as in the case of Lil’Bit and Peck.

In Vogel’s play, how and why Lil’Bit ends her forbidden relationship with Uncle Peck is astounding, if one looks to Vogel’s profound clues of Lil’Bit’s emotions which are an admixture of confusion, regret, love, affection, annoyance, fear and disgust of going legal/public and against family, for example, her Aunt, whom she has “stolen” Peck from. Indeed, Lil’Bit is willing to forget what happened and stop their secret “drives” after she goes away to college. But when she is disturbed by Peck’s obsessive letters, and drinking to excess, she flunks out. She is haunted by the events (sexual grooming in 2022 parlance), that began when she was eleven, so she ends “them.” The last time she sees him is in a hotel room, though at 18-years-old she is of age and old enough for intercourse under the law. However, she must be willing.

Her ambivalence is reflected when she lies down with him on a bed, obviously feels something but gets up. Yes, she agrees to do that after she has two glasses of champagne. But when he asks her to marry him and go public with their affection with each other, it’s over. The irony is magnificent. When they were secret, she let it happen and told no one and continued her drives with him until college. The public exposure of a public marriage is loathsome for her as she would have to confront what has transpired between them for seven years.

As Vogel relates the process through Lil’Bit’s sometimes chaotic flashback/flashforward, unchronological remembrances, we understand the anatomy of Peck’s behavior and hers. The finality of this revelation occurs when she divulges the precipitating abusive event on Lil’Bit’s first driving lesson in Peck’s car. Driving becomes the sardonic, humorous metaphor by which Peck reels her in, linking her desires to his (part of the affectionate aspect of grooming). Her mother (the funny and wonderful Johanna Day), despite negative premonitions, allows her eleven-year-old to go with her uncle, though she “doesn’t like the way” he “looks” at her.

The dialogue is brilliant. Li’l Bit chides her mother for thinking all men are “evil,” for losing her husband and having no father to look out for her, something Uncle Peck can do, she claims. Li’l Bit uses guilt to manipulate her mother to let her go with him. Her mother states, “I will feel terrible if something happens” but is soothed by Li’l Bit who says she can “handle Uncle Peck.” The mother, instead of being firm, says, “…if anything happens, I hold you responsible.”

Thus, Li’l Bit is in the driver’s seat from then on, responsible for what happens in her relationship with Peck, given that warning by her mother. This, in itself is incredible but the family has contributed to this result in their own personal relationships with each other as Vogel reveals through flashbacks of scenes which have psycho-sexual components between Peck and Lil’Bit and Lil’Bit and family members. However, this is a play of Lil’Bit’s remembrance. We accept her as a reliable narrator, knowing that things may have been far different than what she tells us. As she is coming to grips with what happened to her as a child, we must admit, it could have been worse, or better, any of the representations less or more severe. Indeed, she is narrating this story of her teen years as a 35 or 40-year-old who is plagued by the tragedies of the past which include what happens to her Uncle which she may feel responsible for.

During the flashbacks which are prompted by themes of unhealthy sexual experiences (including male schoolmates’ obsession with her large breasts), Lil’Bit reveals prurient details about her family’s approach toward their own sexuality and hers. It is not only skewed, it is psychologically damaged. For example, Lil’Bit explains they are nicknamed crudely and humorously for their genitalia. Her grandfather represented by Male Greek Chorus (the superb Chris Myers), continually references her large breasts salaciously, one time to the point where she is so embarrassed she threatens to leave home. Of course, she is comforted by Uncle Peck who understands her and never insults or mocks her. However, in retrospect, he does this because it’s a part of their “close” driving relationship.

In another example her mother chides her grandmother for not telling her about the facts of life because she was most probably gently forced into sex, got pregnant, had a shotgun wedding and ended up in an unhappy, unsuitable marriage. From the women’s kitchen table of women-only sexual discussions, we learn that grandmother married very young and grandfather had to have sex for lunch and after dinner, almost daily. And with all that sex, grandma never had an orgasm.

When Lil’Bit asks does “it” hurt (note the reference isn’t to love or intimacy or even the more clinical intercourse), the grandmother portrayed by the Teenage Greek Chorus (Alyssa May Gold who looks to be around a teenager), humorously tells her, “It hurts. You bleed like a stuck pig,” and “You think you’re going to die, especially if you do ‘it’ before marriage.” The superb Alyssa May Gold is so humorously adamant, she frightens Lil’Bit so that even her mother’s comments about not being hurt if a man loves you are diminished. Indeed, reflecting on her mother’s unwanted pregnancy and her grandparents’ cruelty forcing her mother to marry a “good-for-nothing-man,” the discussions are so painful Li’l Bit can’t bear to remember their comments “after all these years.”

Thus, romance, love and affection and sweet intimacy are absent from most discussions about men who are neither sensitive, caring, loving or accommodating to her mother (an alcoholic with tips on drinks and how to avoid being raped on dates), and grandmother who never had an orgasm with her beast-like husband. Only her Aunt seems satisfied with Uncle Peck, who is a good, sensitive man, who is troubled and needs her, and who reveals that she sees through Li’l Bit’s slick manipulation of him. She knows when Li’l Bit leaves for college, her husband will return to her and things will be as before. An irony.

Vogel takes liberties in the arc of the flashbacks with intruding speeches by family. As all memories emerge surprisingly when they are disturbing ones, Li’l Bit’s are jumbled. The exception is of those memories which organically spring from the times Peck and Li’l Bit drive in his car as he teaches her various important points and helps her get her driver’s license on her first try. After, they celebrate and he takes her to a lovely restaurant and she gets drunk.

Again and again, Vogel reveals Peck doesn’t want to take advantage of her because he will not do anything she doesn’t want him to do, he proclaims. Thus, his attentions are normalized. And Lil’Bit shows affection yet, at times apprehension, ambivalence and acceptance. On their drives, Peck has become her quasi father figure, a confidant and supportive friend. Thus, she accepts his physical liberties with her (unstrapping her bra, etc).

Because the scenes are in a disordered cacophony, each must be threaded back to the initial event of Peck’s molestation which happens at the end of the play. SPOILER ALERT. STOP READING IF YOU DON’T WANT TO KNOW WHAT HAPPENS.

The mystery is revealed why Li’l Bit continues her driving lessons until she goes to college, and even then ambivalently meets him in the hotel room where he proposes. When she is eleven (Gold stands off to the side reminding us of her age as Parker and Morse enact what happens), she touches Peck’s face as she sits on his lap. While driving, Peck touches Li’l Bit who cannot reach the breaks, but only holds her hands on the wheel so she doesn’t kill them both. Though she accepts what he does initially, then tells him to stop, he ignores her. Then she states, “This isn’t happening,” making the incident vanish, though it happens. And she tells us, “That was the last day I lived in my body.”

It is a shocking moment and is a revelation at the play’s near conclusion. Prior to that Morse is so exceptional we take Peck at his word, that he won’t do what she doesn’t want him to. In the last scene, we see he lies. Likewise, we realize the impact of his horrific behavior on Li’l Bit. When she is twenty-seven as an almost aside, in the middle of the play, she cavalierly tells us she had sex with an underaged high school student, then reflects upon her experiences with Peck. She realizes for Peck, as for herself, it is the allure of power, of being the mentor and teacher to someone younger, using sex to hook them like a fish.

By this point, we have learned that Uncle Peck became alcoholic, lost everything and died of a fall seven years after she never saw him again. At this juncture in her life, perhaps she is reconciling and working through all of those traumatic experiences growing up. And then Lil’Bit tells us of her love of driving as she gets into a car and Peck’s spirit gets into the back seat and races down the road with her as the others stand outside and watch. Indeed, taking Peck with her, the damage is everpresent. Though she will never die in a car, she has learned to destroy others with the driving techniques of allurement, denial and “gentle affection” Peck showed her.

The actors do admirable justice toward rendering Vogel’s work to be magnificent, complex and memorable. With her profound examination via Li’l Bit’s remembrances, we see Parker’s and Morse’s astonishing balancing act inhabiting these characters and making them completely believable and identifiable. The audience tension is palpable with expectation as we become the voyeurs of a slow seduction: we wonder if the cat who mesmerizes the bird will really pounce or the bird merely enthralls the cat, knowing its wings enables it to an even quicker escape, leaving the cat in devastation of its own faculties.

Rachel Hauck’s minimalist set is suggestive of memory without a conundrum of details, just the bare essentials to fill in the locations with the time stated by the chorus (Johanna Day, Alyssa May Gold, Chris Myers). The depth and sage layering of Vogel’s production envisioned by Brokaw disintegrates the superficiality and sensationalism of pundits on the left in #metoo and on the right with #QAnon pedophile conspirators. It echos the tragedy of the human condition and the revisiting of the sins upon each generation who dares to breathe life into the next set of progeny.

Kudos to the creative team Dede Ayite (costume design), Mark McCullough (lighting design), David van Tieghem (original music and sound design), Lucy MacKinnon (video design), Stephen Oremus (music direction & vocal arrangements). This is another must-see with this cast and director who have lived the play since before COVID. You will not see their likes again. For tickets and times go to https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2021-22-season/how-i-learned-to-drive/

Debra Messing in ‘Birthday Candles’ brings a tasty treat to Broadway

Birthday Candles by Noah Haidle, directed by Vivenne Benesch allows Debra Messing to shine as the aging Ernestine who moves from 17 to 107. As she traditionally bakes her birthday cake, over the years, first taught by her mom Alice (Susannah Flood), she gradually understands that she can only realize her dreams by being herself. And all along, getting married, raising a family, getting a divorce and finding the love of hr life, she has achieved her goal, taking her rightful place in the universe.

Haidle’s Birthday Candles, at the Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre, is poetic and complex with multiple themes. The most salient one focuses on Ernestine’s spiritual journey as the “every woman” sustaining emotional pain, trauma, loss, moving from weal to woe and finally reconciling a belated love with great joy in her 80s. As she moves quickly through time, she “looks through a glass darkly” without understanding, until she finally accepts the love and divinity in herself in her relationships with her family and partners. By her 107th year, she misses everyone and wishes them back as she has each time she gives the one passing (mother, daughter, son, grandchildren, etc.) up to the cosmos. Finally, her family spiritually appears and it would seem waits “in the wings” for her to accompany them on the next leg of her journey with them.

Haidle’s conceit about time and life’s passage in the “twinkling of an eye” (in the play 90 years in 90 minutes with some decades speeded up and others truncated) is most wonderful holistically as the characters live in the moments which they can’t fully appreciate. In this play the adage “life is short” is on steroids. Indeed, living one’s life while observing it alters it (a very rough comprehension of the Uncertainty Principle).

Thus, dramatically the play magnifies each character, present in their most vital of moments with Ernestine to heighten her life’s purpose in being herself, a mosaic of moments which come together at the conclusion. It is then that the audience and Ernestine reflect upon her life’s work and the revelation of Ernestine’s beauty is clarified. Of course, at that juncture when her work is finished, she moves to another realm in the starlit space/time continuum.

With the exception of Messing’s Ernestine, the actors portray multiple generationaly linked roles from mother Alice (Susannah Flood), to great grand daughter Ernie (Susannah Flood) with husband Matt (John Earl Jelks), son Billy (Christopher Livingston), daughter (Susannah Flood), grandchildren and forever sweetheart Kenneth (impeccably played by Enrico Colantoni). All these escort Ernestine through the years.

The dialogue and sounding of a bell for the passage of time clues us in to each generation as they come to celebrate Ernestine’s birthday while she bakes her plain butter cake over the 90 minutes of the play. Though birthday candles are never placed on top of the cake, nor is it iced, the title is enough. Indeed, Messing as Ernestine is both the icing and the candles, her soul and spirit, which are invisibly lit for eternity.

Importantly, every word of the dialogue is paramount and must be heard to appreciate Haidle’s depth of meaning, the poetry, the wisdom, the beauty and the sweet golden threads that bind from one generation to the next. In the performance that I saw (Wednesday evening), sometimes the dialogue was muffled and the words, not projected, slung together like a nondescript house salad without dressing. This was tragic because Haidle’s play is brilliant and achingly timeless and heartfelt. The humor is multi-layered and ripe. The conflicts which (if the actors don’t enunciate precisely) appear rather sparse. However, upon review, they are exceedingly well drawn and acute in each twinkle of time over the fast procession of years that transpose and spool Ernestine’s life.

Messing who is an accomplished TV (“Will & Grace”), film (The Mothman Prophecies) and stage actress (Outside Mullingar) is in her glory onstage throughout with “no rest,” (a meme in the play), a veritable tour de force. She is strongest and most poignant in the section of the play when Ernestine reaches a ripe seventy. She has negotiated life on her own terms, has become an entrepreneur, traveled to far flung places and is only taking care of herself. It is then when her granddaughter Alex (Crystal Finn) introduces the next surprising chapter in her spiritual evolution and she learns about reconciliations and renewals, and the fruition of faith and love.

Enrico Colantoni and Messing create the emotional grist for this section of the play which brings a sigh of relief to audience members and shouts from her children. They are truly stunning together and force us to look at those elements that Haidle insists upon in Birthday Candles, the spiritual, the ineffable, the timeless, the eternal. Their relationship which has been growing unseen for Ernestine, always felt to Kenneth, is breathtakingly conceived by the playwright, authentically manifested by Messing and Colantoni. It is the high-point, and Haidle has cleverly made us wait for it, so when it comes we are happily stunned and gratified.

Kudos to the cast when they projected (Colantoni and Messing had no problem) and the creatives: Christine Jones (set design), Toni-Leslie James (costume design), Jen Schriever (lighting design), John Gromada (sound design), Kate Hopgood (original music).

Birthday Candles is on limited engagement. See if before May 29th when it closes. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2021-2022-season/birthday-candles/performances

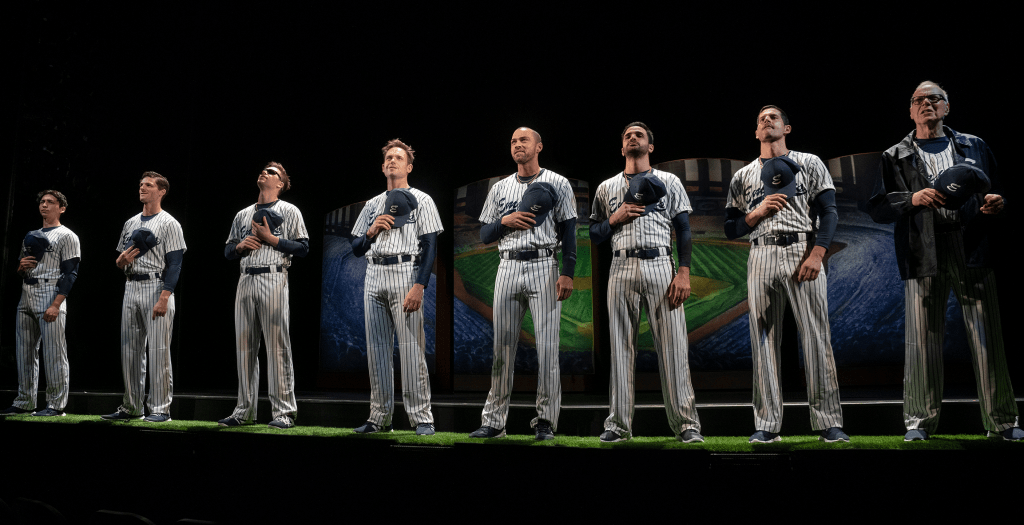

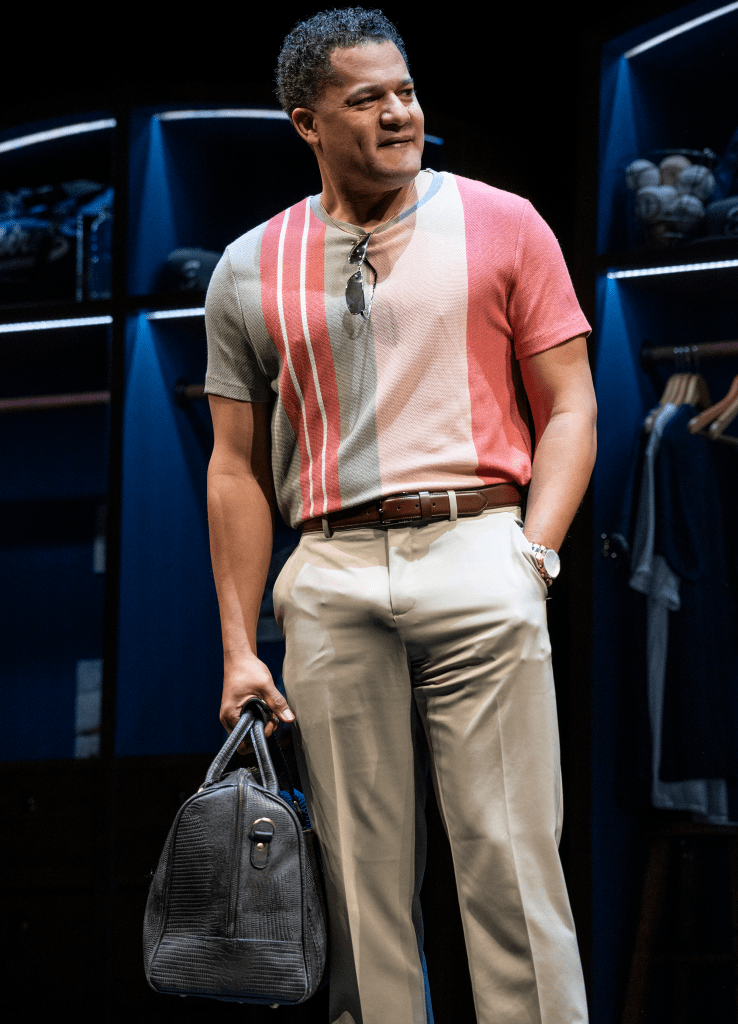

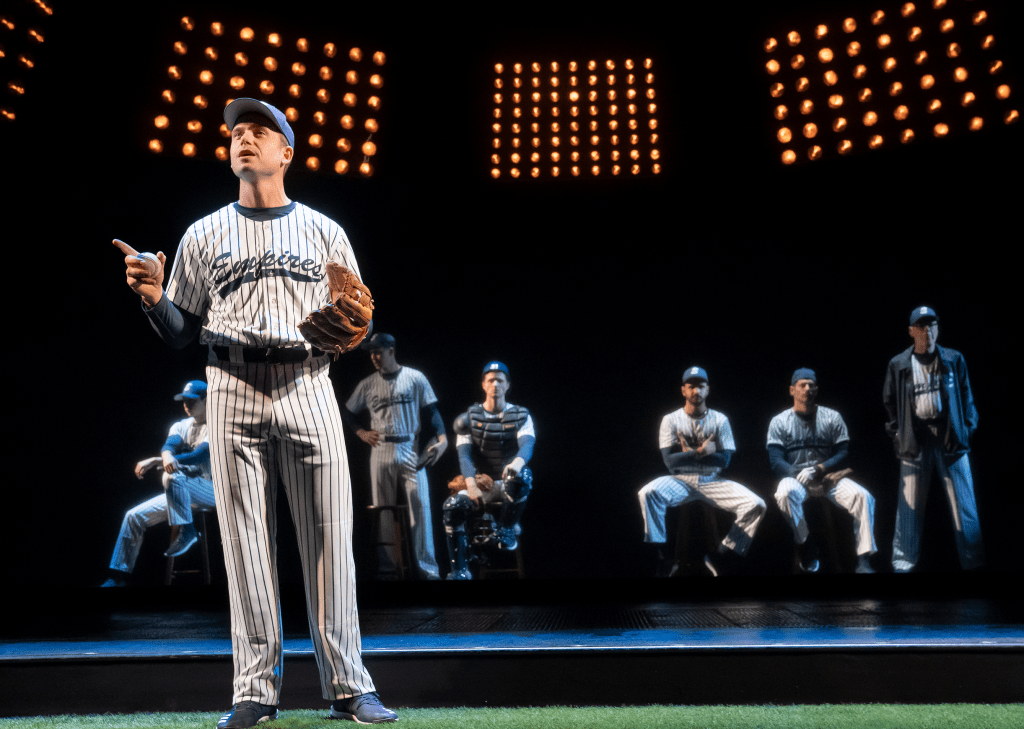

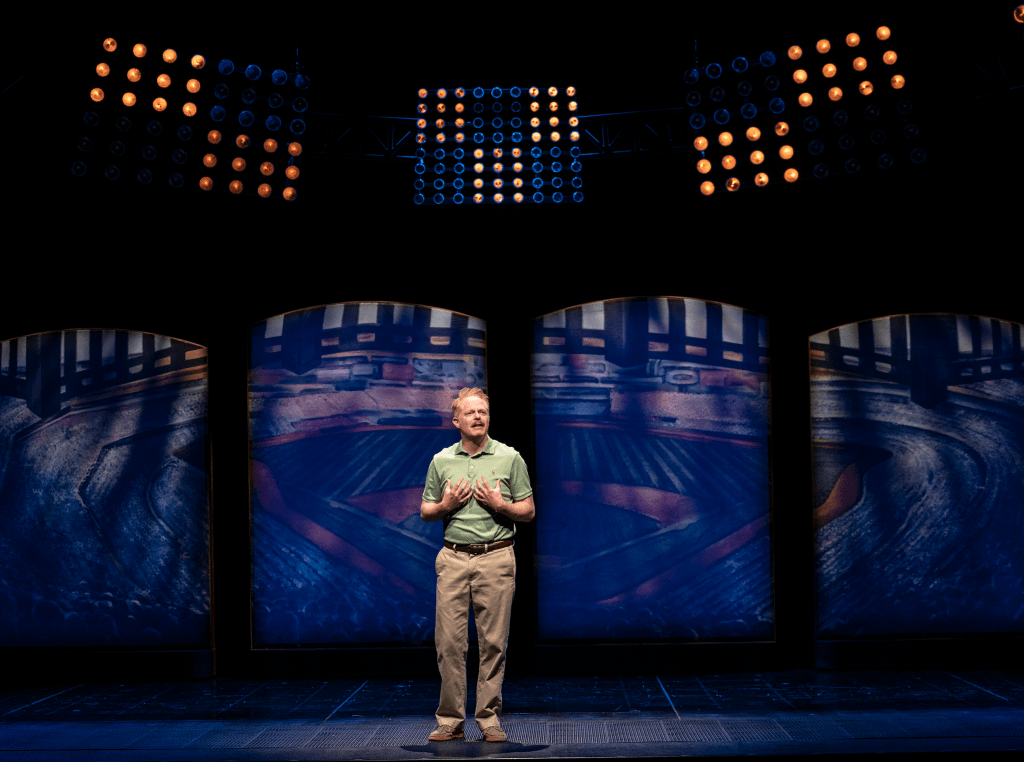

‘Take Me Out,’ the Revival Strikes Deep With Bravura Performances by an All-Star Cast

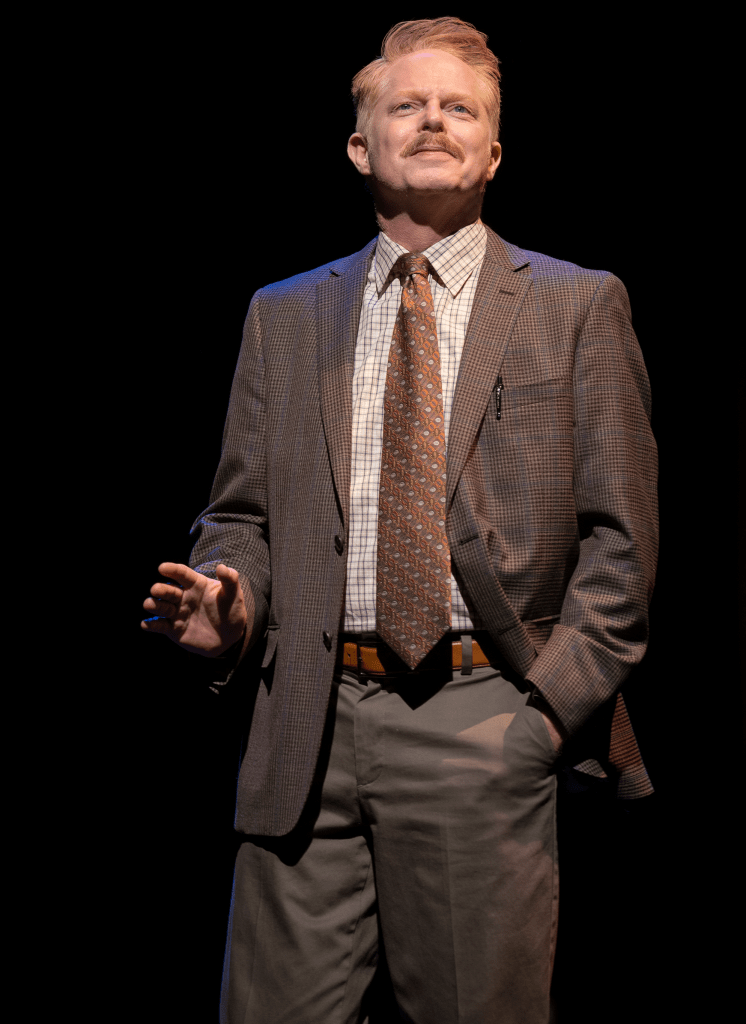

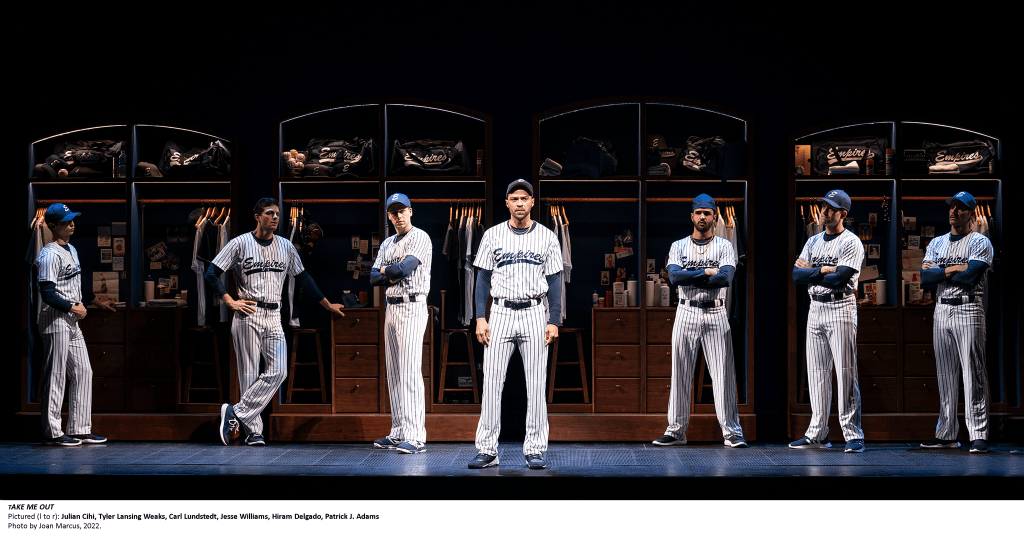

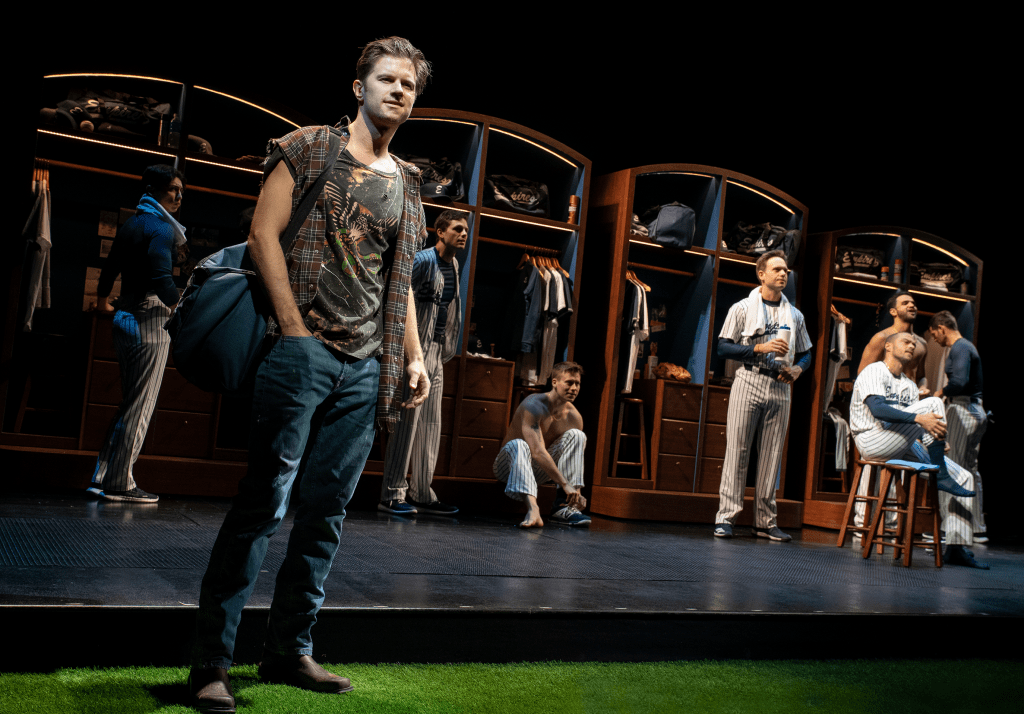

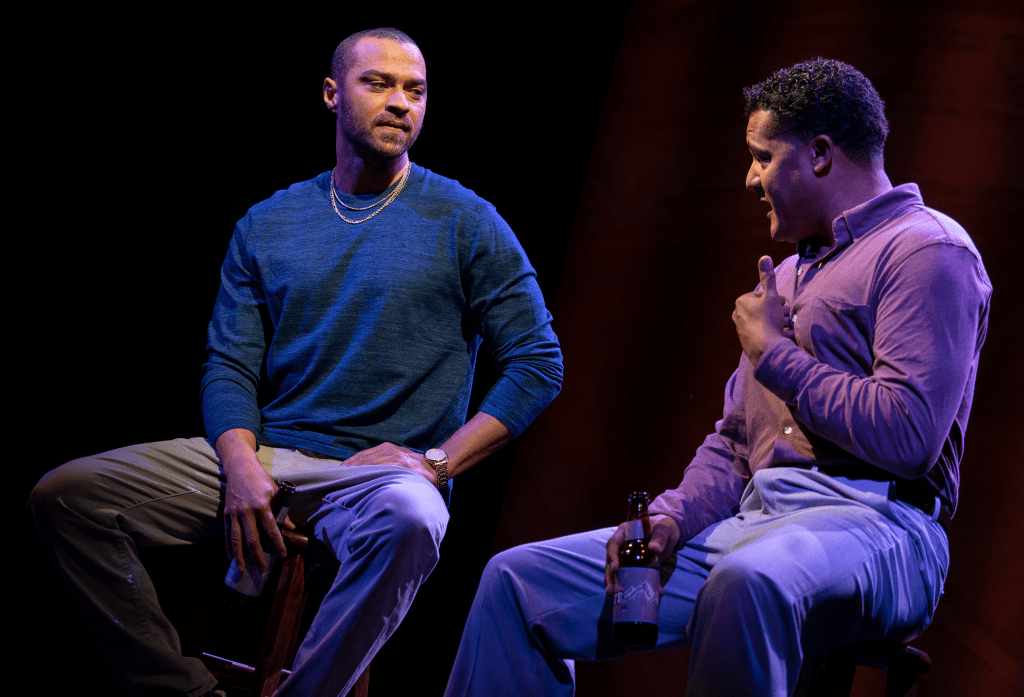

Once again, twenty years later, Take Me Out, the revival for the love of baseball running at 2nd Stage, strikes a pacing home run with bravura performances by Jesse Tyler Ferguson (Mason Marzac), Jesse Williams (Darren Lemming), and Brandon J. Dirden (Davey Battle). Richard Greenberg’s dialogue in the minds, mouths and hearts of the cast never seems more acute, dazzling and dangerous in this “piping time” of Red State/Blue State, as he pumps up the themes of machismo, homophobia, religious bias, gender bias, racism, identity conflicts with color blindness, celebrity privilege, corporate hypocrisy and much more. The second act really takes off, soaring into flight after a perhaps too long-winded first act, whose speeches may have been slimmed a bit to make them even more trenchant and viable.

There is no theme that Greenberg doesn’t touch upon which is current and heartbreaking, except #metoo. That is refreshing because one’s personal rights vs. accountability to the public good are paramount to all spirits inhabiting various bodies whether male, female, transgender, or other. The importance of human rights, human decency and love are crucial in this play because the incapacity of all the characters to embody these qualities remains one of the focal points.

Finally, one does hope that the success of the production will remind all lovers of baseball (the most American of games), that it is the only sport where an active major league player has not come out as gay. As a matter of personal choice and risk, of course, such a decision would be momentous as it becomes for the star of the Empires (think Yankees), Darren Lemming, superbly played by Jesse Williams.

Scott Ellis’ direction is spare and thematically charged. Importantly, “sound” (thanks to Bray Poor, responsible for sound design), heightens the excitement. The emphasis is on the crack of the ball on the bat and the cheering fans. The lighting (Kenneth Posner), is spare. Florescent thin blue lines, representing team colors, square off the space to suggest the players’ emotional confinement. The staging elements rightly place front and center the social dynamic, arc of development and relationships between and among the players.

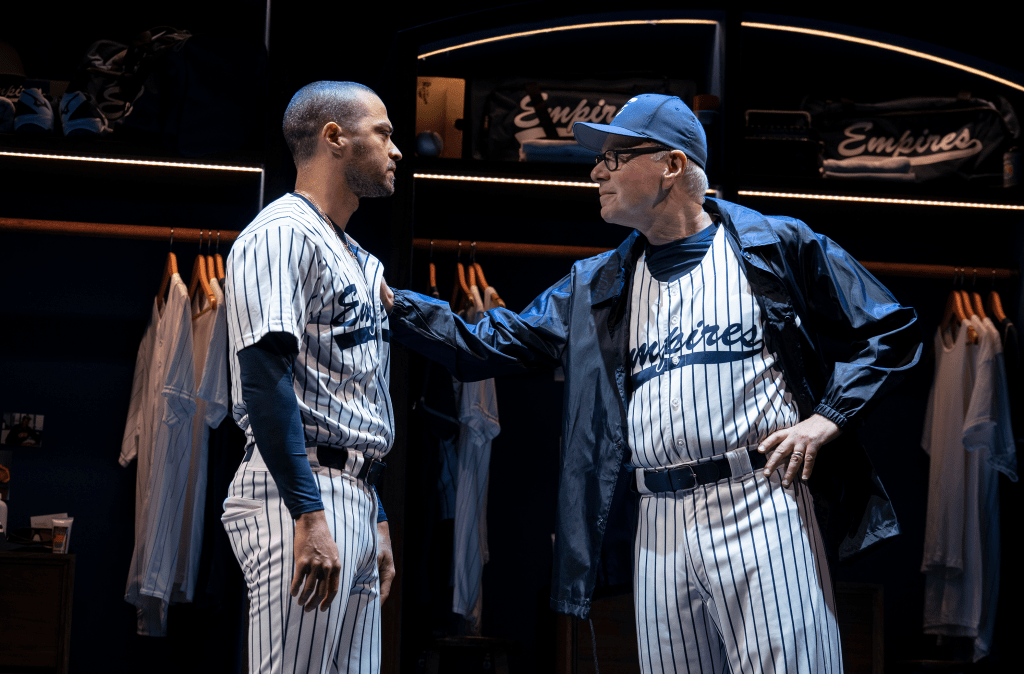

Initially, team camaraderie is thrown into disarray by Darren Lemming, who drips gold from his pores and walks upright in perfection but admits to being gay. His proclamation sends ripples of “shock and awe” through his envious teammates, who worship Lemming’s “divinity,” his steely cool demeanor and very, very fat salary,

We find his teammates response to be humorous. In order not to appear femme they restrict all their male “locker-room” behaviors because they don’t want to “entice” Darren into thinking they are his sexual “kin.” Only Kippy, his self-appointed buddy and narrator who tells part of the story (the fine Patrick J. Adams), chides him for not alerting anyone before his press announcement. Afterward, Kippy humorously teases his friend that the team lionizes who he is and would love to “be him” or “be with him,” on the down low, except that he is now very public. And that would make them very public. So they must keep their distance. Darren is annoyed at this new leprosy which he never experienced or thought he would experience because he is who he is, the team’s greatest.

Meanwhile, Darren’s announcement has forced all to confront where they stand with their own sexuality and sensitive male identity, which Kippy suggests reveals latent gay repression, and Darren suggests is the opposite. From the initial conflict, the Empires go through a roller-coaster of events and emotions that Darren didn’t foresee when he blithely walked between the raindrops and dropped the bomb on his team and Major League Baseball, assuming that because he could handle it, they should handle it.

When it comes to his devoutly traditional Christian friend Davey Battle (the always excellent Brandon J. Dirden), Darren has a blind spot. Instead of quietly discussing his sexual orientation with Davey, a misunderstanding ensues when Davey encourages him to be himself and be unafraid.

Where certain Christians are concerned, being gay is another feature of Christ’s love. Darren assumes that especially with his devout Christian friend, Christ’s love means acceptance. Greenberg holds back the mystery of Davey’s and Darren’s conversation about his being gay, revealing its importance at the end of Act II, when the stakes are at an explosive level. When we discover the identity of the individual who overhears their conversation is a witness to “the event,” we are surprised at the superb twist. Immediately, we understand the conversation happened. There is no way the “overhearing witness” would be lying. It is this conversation that becomes the linchpin of uncertainty, a tripwire to set off questions with no easy answers. There is no spoiler alert. You’ll just have to see this wonderful production to find out the importance of the witness to the conversation.

Greenberg covers all his bases with runners in this take down and resurrection of America’s “favorite past-time.” There is personal locker room talk where nude teammates “let it all hang out,” as they shower and face-off against each other, responding to Darren’s announcement and humanizing him because of it. Greenberg’s wit and shimmering edginess work best, revealing his spry characterizations in the banter between Kippy and Darren, and in the growing friendship between Darren and his new financial advisor Mason Marzac, the superbly heartfelt and riotous Jesse Tyler Ferguson. As the consummate outsider who becomes a fan, the character of Mason has the most interesting perspective on baseball, the gay community and the events that happen in real time that result in an unresolved tragedy.

Marzac, meets with cool, collected Darren after the celebrity star outs himself. Ferguson’s Marzac is humorously over the moon about Darren’s courage, his performance and the game. Darren states coming out was not “brave,” unless one thinks something bad will happen, because “God is in baseball,” and Darren is in baseball. And “nothing bad happens to Darren.” This Icarus is flying high. He takes advantage, surreptitiously, smoothly crowing about his stature which outshines his teammates and especially the awe-struck dweeby, unathletic, unbuff Mason.

Of course, the conversation carries tremendous irony in hindsight, because like Icarus who gets burned and crashes to the earth, so does Darren. How Greenberg fashions this is surprising and ingenious. Interestingly, not only does Darren take the team with him emotionally and psychically, they are rewarded despite their corrupt Machiavellian machinations to achieve a win. The irony is heavenly. It is Greenberg’s device, savvy and sardonic, which speaks to theme. Sometimes when you win, it’s not a win if your heart breaks and there are no friends or teammates you can share it with because of emotional separation and alienation. So for the team and especially Kippy and Darren, the win becomes a grave loss that no one can ever appreciate, except baseball idolator, Mason.

But I get ahead of myself praising Greenberg’s irony.

As they discuss Darren’s financial picture, Darren clues Ferguson’s Mason in to the finer points of baseball appreciation, for example to keep “watching” the number coincidences. There’s “a lot of that,” Darren implies as Mason rattles off wondrously, “…the guy who hit sixty-one home runs, to tie the guy who hits sixty-one home runs, in nineteen sixty-one, on his father’s sixty-first birthday.” Mason is ignited by speaking to the amazing and surprisingly gay Darren.

Ferguson shines in his Mason portrayal, as he excitedly waxes over the Americanisms of the game, as pure egalitarian democracy. He emphasizes that everyone has a chance when they get up to bat. But then he states that baseball is more mature than democracy. This comment coupled with the arc of development is an incredible irony considering the team takes in a crackerjack pitcher, Shane Mungitt, who is one of the more florid Red Necks to ever appear on stage. Michael Oberholtzer’s Shane is breathtaking, a stellar, in-the-moment portrayal of a bigot you can actually feel sorry for.

Ferguson’s superbly rendered soliloquy about baseball opens a window into Mason’s kind, perceptive and loving nature. He effusively and humorously describes the requisite home run as a unique moment: the game stops and there is a five minute celebration of cheering time for the fans and the hitter, who rounds the bases like a king, though the ball has long spiraled out of the stadium into the universe. From watching the completely unnecessary round of the bases, Mason says, “I like to believe that something about being human is good. And what’s best about ourselves is manifested about our desire to show respect for one another. For what we can be.”

This is the crux of the play because after this eloquent and high-minded speech, everything falls apart. The winning streak of the Empires, the team relationships, the friendships between Davey and Darren, and between Darren and Kippy implode. And sadly, the once silent, “mind my own business” Shane unravels into a hellish state, careening into the other players with a vengeance that he may not be responsible for, given his upbringing. Thus, not even a winning season saves them from the inner reckoning they have brought upon themselves. If this is America’s favorite past time, it would be better to go back to reading.

Greenberg gives his play’s coda to Mason, who has “evolved” into a baseball aficionado. As such he is brimful of hope, yet ironically perceptive. A tragedy has occurred. However, for him the greater tragedy is that he has to wait a whole half year for the season to begin again. Baseball is that tiny thing that takes one out of the misery of life and makes it worth living, even with its tragedies. In Take Me Out, that is true for the fans. For the players, what occurs is an entirely different and terrible consequence.

Kudos to Scott Ellis’ direction and his shepherding of cast and the creative team. These include Linda Cho (costume design), David Rockwell (scenic design), and others already mentioned. Scott Ellis and the cast have delivered a profoundly humorous and vital, resonant work about a game played throughout our country, revealing that no one, regardless of how we prize sports figures, is worthy of the greatness of the game itself.

For tickets and times go to the website: https://2st.com/shows/take-me-out?gclid=Cj0KCQjwjN-SBhCkARIsACsrBz798inP5l5pUV7hZGFHOj0rWRI1spG27oalp8HyLfnArPnBlPauavsaAkcwEALw_wcB

The ‘Plaza Suite’ Snark is Disingenuous #metoo

In his snarky review of Neil Simon’s Plaza Suite, the New York Times’ critic’s “clever,” oh so “entertaining” disposal of the John Benjamin Hickey production into the garbage bin of hideous fustiness seems misguided. To the critic’s dunning I shout, “Au contraire!” The production starring Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker offers a unique, glimmering reflection of the past. It is a past that we need to be reminded of. If one peers into that reflection, and considers the interactions of the characters, one sees how intelligent females bested their male counterparts with surreptitious abandon, superior wit, and brilliant irony. If one’s view is dim and dark, like the NYT critic, one sees little.

From my humble female perspective, one also considers via this production, that between then and now, with all of the hell raising and insistence on progress, and change between straight men’s and women’s relationships, nothing much has changed. Don’t believe me? Have you read any good Evangelical books lately? Have you lived in the South for any period of time, recently? All right, maybe that doesn’t make sense to you.

Well, I will remind you about that pesky statistic (one in four women are violently abused by their partners), that has yet to budge off its number. Abusing females is alive and well, and that’s despite #metoo which is a meme that only applies to the celebrated, rich and famous, including well-paid male theater critics. In plebian circles if a woman attempts to speak up, a hand often goes upside her head. And what happens after that is anyone’s guess.

That Simon exults in the superiority and cleverness of each of the female characters in the play is lost on the critic which is understandable as he is not a female. He is a male looking in and once again judging the female characters and finding them and the production fusty, dusty and musty. Unfortunately, he shallowly superimposes his #metoo version of the female perspective on the characters, thus making the push to be politically correct all the more hypocritical and disingenuous. And frankly some of it is nonsensical, though there appears to be “logic” in what he is doing because the piece is well edited. Is his editor a male too?

Ah, forget what I just stated. Be overwhelmed by the “smart attitude” of the New York Times critic who displays his own “genius,” sense of privilege and arrogance via his male writerly superiority, which is nowhere near the genius of say, Gore Vidal (a favorite of mine). So caught up in admiring his style in the mirror, he misses the themes and the currency of Hickey’s vision. He also misses the fact that relationships between men and women have gone nowhere because human misunderstanding and fear and inability to confront death and lies by keeping them at bay through self- manipulation is an everpresent fact encompassing the relationships, in Plaza Suite.

But none of that was picked up by the critic to whom the 1960s was such a thing of the past, it doesn’t exist in his imagination; nor does he appear to want to be reminded of it, if it did exist.

Instead, what is of great importance to him, it would seem, is bowing to politically correct memes. Tragically, that is a blindness and acute hypocrisy. Currently, I boycott the New York Times. I am tired of the same pap from this particular NYT critic whose dullness would be raw meat for Noel Coward, if he were alive. I stumbled upon the review clued in by a studio professor, and well-produced playwright who mentioned the tenor of the review because he knows such pablum makes me livid.

The privilege he displays is a long-held tradition at the New York Times. Females, largely absent in theater as critics, directors, etc., commented upon by Director Rachel Chauvin in her acceptance speech for Hadestown is an example of how #mettoo doesn’t work in the theater world. Perhaps the reason is that female critics and reviewers are not #metoo politically correct enough. Perhaps females don’t remind us enough that various productions are not “politically correct.” Shall I discuss LGBTQ?

Truly. Perhaps for future productions directors and producers should wipe out the canon of plays written before 2017 and #metoo, etc., as worthless. What could possibly be learned from them?

Indeed, if critics are to genuinely benefit audiences who see plays, then they must perceive, think and above all go deep. First, understand what the director’s vision is. Is the director presenting that which on first assumption perhaps the critic didn’t get? Does it pass the audience test?

The night I saw the production, Plaza Suite did pass the audience test. They enjoyed it. Thus, I agree to disagree with the NYT and the Wall Street Journal critics. The below review, which also appeared in Sandi Durell’s Theater Pizzaz explains why.

My Review of Plaza Suite: A Female Perspective

Judging by the applause as the curtain lifts and John Lee Beatty’s luxurious, shimmering set for Plaza Suite unveils, director John Benjamin Hickey’s glorious throwback to the gilded Broadway of “yesteryear,” intimates a night of enjoyment. Coupled with its second harbinger of success, enthusiastic cheers at the entrances of the husband-and-wife team Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick, the Neil Simon revival emblazons itself a smash even before Karen (Parker) and Sam (Broderick) have their first disagreement.

Not one moment falters in the pacing or mounting crescendo of hilarity in this superbly configured production about a suite of rooms (a conceit knock-off of Noel Coward’s Suite in Three Keys). There, visitors from Mamaroneck, Hollywood and Forest Hills play out their dreams and face their foibles in room 719 at the historic Plaza Hotel. That the place is still standing is a source of Simon witticisms.

Apparently, rumors of its being bought over by rapacious developers to be torn down making way for state-of-the-art buildings even existed at Simon’s writing. The theme of the ugly new replacing the beautiful old and historic as a pounding mantra of New York City is everpresent and a sometime theme in the triptych of playlets about couples.

Hickey shepherds Parker’s and Broderick’s performances, delivered with “effortless” aplomb, gyrating from one comedic flourish to another to the amazing farcical finale. Authentically and specifically (gestures, mannerisms, presence, posture), they hone the characterizations of three disparate couples, breathing into them the humanity we’ve all come to love and loathe. We didn’t want the fun to end, and it was apparent that neither did they.

The few times they broke each other up or comfortably ad libbed, they let the audience in on the endearing fact that they were having a blast. That mutuality between audience and performers was doubly so because they’ve been waiting to perform for two years of COVID hell. Happy to be back in front of a live audience, their enthusiasm was communicated by the ineffable electricity that happens in live performance and changes nightly because of the audience’s diverse sensibilities. The performers vibrated. The audience vibrated back. The circle completed and rolled around for the next laugh which topped the next.

Ingeniously entertaining, incredibly performed, Plaza Suite at the Hudson Theatre which runs for a limited engagement is a spectacular winner. Here’s why you should see it.

Though Neil Simon’s concept that he lifted from Coward has been reshaped and used by playwrights and screenwriters since the 1960s when Simon wrote Plaza Suite, the production gives it a unique uplift because of its specificity and attention to detail. Importantly, viewed through a historical lens, the relationships, character intentions and conflicts ring with comical verities. Wisely, Hickey allows the characters inhabited by these sterling performers to chronicle the values and folkways of the sixties which were a turning point in our society and culture. The understanding that arises from Simon’s exploration suggests why we are where we are today.

Finally, using humor the play deeply touches on seminal and timeless human topics: fear of aging, seduction, loneliness, marriage unsustainability, the generation gap and more.

In the first playlet, Karen’s Mamoneck housewife chafes in a relationship which she unconsciously senses has soured. She books Suite 719 to celebrate her anniversary with Sam and ironically initiates the reverse.

Listening carefully and watching Parker’s Karen, noting her plain outfit and hairstyle and comparing it to Broderick’s Sam, the laconic, dapper, sharp, appearance obsessed businessman, we should anticipate what will happen. We don’t because Simon’s keen, witty dialogue of thrust and parry between Sam and Karen keeps us laughing and because the performances are so spot-on, in the moment, we, like the characters, don’t know what’s happening next. However, of course, Broderick and Parker do. Yet, they are so alive onstage, that the characters’ reactions remain a surprise and the revelations are unanticipated.

Karen’s ironic subtext brilliantly digging at Sam to confess he’s having an affair is wonderful dialogue expertly delivered. A few of Parker’s lines bring down the house with her sharply paced delivery. One is her crackerjack response to Sam’s “What are we going to do.” Without a blink Parker’s “You’re taken care of. I’m the one who needs an activity,” receives audience whoops and hollers. An age-old event of cheating and adultery is born anew.

Simon’s snapping-turtle dialogue in the face of today’s hackneyed insult humor is wickedly scintillating. In the Hollywood seduction playlet, High School sweethearts become reacquainted. Broderick’s smarmy Hollywood producer Jesse Kiplinger decked out in his Mod finest is a classless nerd who confesses his unhappiness with the Hollywood slime set and his three *&$% ex-wives who take not only his money but his guts and soul. Muriel in Parker’s equivalent of her fashionable self in the ‘60s, is enthralled by Jesse’s Hollywood persona, but is in keeping with the innocent, demure women Jesse remembers. The hilarity builds into what becomes a reverse seduction scene by a steaming married woman when they “get down to brass tacks.”

All stops are pulled in “A Visitor from Forest Hills.” The costumes (Jane Greenwood), the hair and wig design (Tom Watson), contribute to building the maximum LMAO riot. The inherent action and zany organic characterizations by Broderick and Parker augment to hysteria when Mimsey refuses to attend her own wedding and ensconces herself in the bathroom.

Norma and Roy implore Mimsey attempting to psychologically manipulate her and each other to get her to come out. Parker and Broderick effectively create the image of their daughter crying, possibly suicidal, as she remains unseen, silent and incorrigible behind the sturdy, unbreakable bathroom door. Desperate to stem a disastrous day, Broderick’s “out of his mind with frustration” Roy even goes out on the ledge and braves a pigeon attack and thunderstorm to wrangle in his wayward child. Broderick’s mien and gestures bring on belly laughs.

What they do to move heaven and earth to get Mimsey to come out is priceless comedy that is easier than it looks. The frustration and fury the actors convey with the proper balance to appear realistic yet crazy and smack-me funny is what makes this over-the-top segment fabulous.

Kudos to the artistic team which includes Brian MacDevitt (lighting design) and Scott Lehrer (sound design). For tickets go to https://plazasuitebroadway.com/

Hugh Jackman’s Indelible, Winning Con in ‘The Music Man,’ Just Unbeatable!’

Historically, America is the land of con artists and showmen. Do you know the difference? As a relatable example there is David Hannum who in the 1850s bought the “Cardiff Giant,” a stone statue he unwittingly believed to be real (the giant fake was made in Iowa). As did its previous owner, Hannum charged admission for viewings. When P.T. Barnum (Hugh Jackman portrayed Barnum in The Greatest Showman) couldn’t purchase the Cardiff Giant for $50,000, he made his own plaster statue, called Hannum’s statue the fake, and charged more money, advertising his as the “real” one. Hannum sued Barnum and referring to Barnum’s patrons said, “There’s a sucker born every minute,” not realizing he, too, had been duped. The suit failed when the originator of the hoax “came clean.” Interestingly, all three entrepreneurs probably kept the money “they earned” providing a thrilling show. In keeping with the great cons of America, history is silent about whether patrons got their money back.

This exploration of that type of con is at the core of Meredith Willson’s The Music Man, which I’ve come to appreciate on another level with this revival at the Wintergarden Theatre, starring Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster. Along with these romantic leads are Shuler Hensley, Jefferson Mays, Jayne Houdyshell and Marie Mullen. All are Tony Award winners. All give humorous, memorable performances in this fanciful, exuberant, profoundly conceived production (directed by Jerry Zaks and choreographed by Warren Carlyle), about small town America, its bucolic, “nothing is happening here” townsfolk, and the burgeoning love between two needy, flawed individuals, who grasp at hope in each other.

With book, music and lyrics by Meredith Willson and story by Meredith Willson and Franklin Lacey, the great con is spun by a magic-making, uber-talented, artiste extraordinaire that all fall in love with by the conclusion (including the audience). That is all except non-believer, malcontent salesman Charlie Cowell (the excellent, hyper-caustic Remy Auberjonois who was in Death of a Salesman). He’s the “villain” who seeks vengeance to expose Hill as a wicked, flim-flam man.

Hugh Jackman is spot-on in his modern interpretation of the Professor Henry Hill “brand” of “music man.” He and Zaks really get this character, so that Jackman makes it his own, as he exudes the energy-packed, brilliant, larger-than-life, loving individual that you want to stay with, wherever he takes you. After seeing his performance, I believe in pied pipers, who don’t need music to make you theirs.

The criticism that he is not edgy is questionable. If Jackman’s Hill were sinister, few would believe his sincerity in a small town that prides itself on suspicion and being “Iowa Stubborn.” Would the women be so taken with his graceful, smooth, charmingly flirtatious manner? He is a swan among the ungainly, quacking mallards and especially his nemesis, the punchy, exasperated, malaproping Mayor Shinn (the always hysterical and exceptional Jefferson Mays), who gaslights the town with his own con. That this genius craftsman of BS has an irresistible delivery reveals Jackman enjoying expanding the graceful Professor in pure entertainment, with every precious breath and every savvy movement he expends, as he inhabits his refreshing version of Professor Harold Hill for the ages.

Hill’s seductive, adorable, spirited demeanor is dangerously addictive. The happy-go-lucky showman is all about getting others to believe in and enjoy themselves. From that elixir, there is no safe return and the crash, if there is one, is emotionally devastating. How Zaks, Jackman, the cast and creative team spin this rendering is solid and logical throughout, giving this extraordinary revival a different feel, understanding and vision, that should not be underestimated or ignored.

Throughout the dance numbers, which are beautifully conceived with wit and substance, Jackman’s lead is ebullient, light, lithe. This is especially so during his convincing, playful seduction in the number “Marian the Librarian” (Warrent Carlyle’s ballet in soft shoe tempo is just great). Jackman’s sensual, boyish suppleness contrasted with Sutton Foster’s stiff reticence in Marian counterpoint are superb together.

For the song identifying the Iowan’s walled stronghold against strangers (“Iowa Stubborn”), Hill’s great challenge, Zaks stages River City citizens huddled together in a circular clump with stern looks and unsmiling determination. Initially, with Hill they pride themselves on being cold steel like Marian, who is even more icy remote than they are. However, because of Charlie Cowell’s challenge, that Iowa territory is impossible for salesmen, Hill takes the bait and rises to the occasion. He plies his delightful winsomeness with enough sincerity and great good will to surreptitiously penetrate their pride.

Not only are the townsfolk splintered from their stubborn resolve because of his contagious enthusiasm, his youthfulness retains a sociability that is able to connect with young and old. Indeed, Hill offers them something that no one else who has come to their town has ever offered: happiness, hope, fantasy, the power to believe; to think something is so and it becomes so (the “Think System” re-framed from “the power of positive thinking”). Jackman’s Hill is a practiced master at human nature-buffeted by life’s heart-breaks, that create the foundation in the soul, that hungers to believe in something or someone. Of course, he is a master at this, because he, first and foremost, is starving, a clue to this Hill portrayal, upon which turns the arc of development and all the character interactions. It is also the theme of “Sadder But Wiser Girl,” that he sings in knowing “wisdom” with buddy Marcellus Washburn (the excellent Shuler Hensley).

The brilliance of this production is that Hill’s charismatic delivery of the dangerous idea is palpable, adorable and expansive. As apparently unrealistic as Hill’s disarming positivity is, it is like manna from heaven for these homely folks, who cannot resist just a taste. And Jackman’s Hill enjoys spoon feeding it to them like sugar, until they are hooked. Interestingly, he also is hooked…on their joyous response to him.

In his backdoor discussions with his comrade in arms, the affable and in love Marcellus, the winning Professor Hill has no disdain or ridicule for those he mesmerizes. He enjoys the challenge (more in the style of 110 in the Shade’s rainmaker Bill Starbuck), of instilling confidence in others and, in return, receiving what he needs, enjoyment, fun, affirmation. He is the antithesis of the bombastic, arrogant traveling salesman loudmouths like Charlie Cowell and the others in the rhythmically pounding opening train number “Rock Island.” (another superb staging by Zaks, et. al.)

Willson reveals the vital difference between them and Hill, as they ride the rails and complain about how hard their job is because of encroaching progress. What an incredible opening scene that gives the set up (costumes, staging, sets, music, sound, tone, tenor). Challenged by their comments that Iowa is an impossible territory, Hill shows himself up to the task, gets off the train, turns to the audience and presents Professor Harold Hill. Just looking at Jackman’s unabashed, open smile and shining spirit, we believe as Mrs. Paroo does, that he can do nearly anything, even if it is getting her very shy son Winthrop to speak, which he does, as Winthrop flows forth in a burst of excitement and emotion that never stops afterward in “Wells Fargo Wagon.”

His product, unlike Charley Cowell’s and the others, is intangible. Thus, taking folks’ money is done quickly, painlessly for much more is being given, including a loving manner and wish to spread joy. In this version of Hill it is his endearing vulnerability to love that Jackman makes believable in his deepening interactions with Marian, whose loving support he has, before the two of them realize it. Jackman and Foster construct this surprising discovery beautifully in the Footbridge scene (“Till There Was You,” and the melding of the relationship as they conjoin their singing of the double reprise “Goodnight My Someone” and “Seventy-Six Trombones”).

The town’s seduction is inevitable after “Ya Got Trouble” and “Seventy-Six Trombones,” an incredible dance number (and pantomimed instrumentation), that Jackman and the cast just kill. River City has “swallowed his line” (the fishing metaphor is used throughout), as does young Winthrop (Benjamin Pajak in a show stealing performance), who is thrilled when his mother, like the other townspeople, signs on for instruments, uniforms and instruction books to form the showy band Hill promises for the absolute thrill of it. That they must learn to play is subtly whisked off until “later,” the “will-o-the-wisp” magic Jackman’s Hill seamlessly performs.

Hill is gloriously, attractively spell-binding. He draws the town to him bringing togetherness and good will, that goes a long way to diffuse the backbiting of the women against Marian’s standoffishness (“Pick-a-Little, Talk-a-Little”). He helps to mend the ladies’ divisiveness, which further draws Marian to them and himself. Humorously, he unifies feuding officials in the exquisite harmony of a barbershop quartet, that they can’t seem to get enough of, once he starts them off on the right chords (“Sincere,” “Goodnight Ladies,” “Lida Rose”). One by one each potentially thorny group falls under Hill’s flirtatious, delectable, gentle power and inspirational artistic encouragement. Talk about soft power flying under the radar, he hits folks’ hearts for a bullseye every time.

In beautifully staged moments by Zaks, we see Hill’s influence on the Mayor’s wife, Eulalie Shinn and her friends, who create dance numbers and other entertainments. Jayne Houdyshell as Shinn is marvelous and LOL in her dancing and primping poses, after Hill’s maximum attentions. The costuming for these scenes is exceptional. Throughout, the costumes are a take-off of 1912 fashion but with the variety of patterns, in some scenes earthen tones, other scenes fun hats, shoes and accoutrements, thanks to Santo Loquasto, who also did the scenic design.

Marian’s costumes are straight-laced without frills by comparison; her hair (Luc Verschueren for Campbell Young Associates), like the other ladies is in fashion, an up-sweep like her mother’s, Mrs. Paroo (the wonderful Maureen Mullen). Attention in this detailed crafting reveals Marian’s restraint, her career and character, providing the subtext and interesting contrast to the other open-handed, more extravagantly dressed woman. Eulalie and her hens are encouraged to believe in themselves in Hill’s sincere admiration as they ooze his charm back at him and titter. In the case of Marian’s response to Hill’s starlight, she moves from grimace to smile to grin.

Importantly, the women are drawn into Hill’s net, however, it’s mutual. Jackman’s Hill is having a rollicking time becoming enamored of them. This portrayal makes complete sense. Because he is lured by their, acceptance and trust in mutual feeling, he is unable to escape when the love net closes around him. Jackman and Zaks have broadened that net to include the townspeople’s acceptance and love as well as Marian’s, her mother’s and Winthrop’s. Zaks shepherds the actors to forge that budding love and trust with specificity and feeling each time they share a scene (i.e. the fishing scene with Hill and Winthrop).

Fear has no place in Hill’s magical world. So when it attempts to enter in the form of Mayor Shinn’s grave doubts about Hill (though Shinn’s motives are financially suspect), he is misled by Marian and his officials, who by this point in time, understand Hill is bringing new life to the community. Thus, they allow themselves to be distracted away from Shinn’s mission to verify Hill’s identity. It’s apparent that with the exception of Mayor Shinn, whose agenda Hill upends by dunning his new pool table, the town’s spirited happiness is heartfelt. One wonders what their lives were like before his enchantments blinded them? Or did he give them a new way of seeing? And what was Hill’s life like traveling one step ahead of the sheriff before he hit River City, an unintentional stop on his route to anywhere U.S.A.?

Clues are revealed in the large set backdrops of the Grant Wood style paintings (Regionalism, note the painting “American Gothic”), that are at once simplistic and complicated in their being two-dimensional, brimming with sub-text. These brilliantly reveal the time, place and characters with details of tone, tenor and color. This is especially so against the green rolling hills Grant Wood backdrop, where the tiny, animated, red, Wells Fargo Wagon races down a hill in the distance as it approaches River City. The audience gasped in awe at the ingenious contrivance. Then, they gasped even louder as the “larger-than-life” Wells Fargo Wagon materialized on stage. Pulled by a well-groomed, shiny-coated, smallish-looking “Clydesdale,” Hill beamed atop the wagon as it stopped, the cast sang “The Wells Fargo Wagon” exuberantly, and Jackman rhythmically tossed out the brown, paper wrapped “instruments.” Poignantly, Pajak’s Winthrop sings, lisp and all, completing the effect. Pure dynamite!

This is the show’s “Singing in the Rain,” moment. It is the still point in time that clarifies and represents the whole; action, event, music, symbolism, lighting and spectacle reveal the theme and its significance to the characters and audience. It is here that we understand the treasure that Hill brings, the heightened glory he coalesces in a happening that the townspeople and a now confident Winthrop, (whom we fall in love with along with Hill), will never forget. And for that reason, Marian destroys the evidence that can sink Hill. It’s a stirring, fabulous end to Act I.