Category Archives: Lincoln Center Theater

‘Ragtime’ is Magnificent and of Incredible Moment

Between the time Lear DeBessonet’s Ragtime graced New York City Center with its Gala Production in 2024, until now with the opening of DeBessonet’s revival at Lincoln Center, our country has gone through a sea change. The very core of its values which uphold equal justice, civil rights and due process are under siege. Because our democratic processes are being shaken by the current political administration, there isn’t a better time to revisit this musical about American dreamers. Ragtime currently runs at the Vivian Beaumont Theater until January 4.

DeBessonet has kept most of the same cast as in the City Center Production. The performers represent three families from different socioeconomic classes. In each instance, they face the dawning of the 20th century with hope to maintain or secure “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” in a country whose declaration asserted independence from its king. In affirming “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all ‘men’ are created equal,” America’s promises to itself are fulfilled by its citizens. Ragtime reveals who these citizens may be as they strive toward such promised freedoms.

Above all Ragtime is about America, the saga of a glorious and terrible America, striving to manifest its ideals and live up to them, despite overarching forces that would slow down and halt the process.

Based on E. L. Doctorow’s classic 1975 historical novel, and adapted for the stage by Terrence McNally (book), Stephen Flaherty (music), and Lynn Ahrens, (lyrics), Ragtime‘s immutable verities are heartfelt and real. As such, it’s a consummate American musical. DeBessonet’s production celebrates this, and superbly presents the beauty, tragedy and hope of what America means to us. In its concluding songs (Coalhouse’s “Make Them Hear You,” and the company’s “Ragtime/Wheels of a Dream”), the performers express a poignant yearning. Sadly, their choral pleading is a stunning and painful reminder of how far we have yet to go to thoroughly uphold our constitution.

The opening number “Ragtime,” introduces the setting, characters and suggested themes. Here, DeBessonet’s vision is in full bloom, from the lovely period costumes by Linda Cho, David Korins’ minimally stylized scenic design, DeBessonet’s staging, and Ellenore Scott’s choreography. As the company sings with thrilling power and grace, they gradually move forward to take center stage. They are one unit of glorious interwoven diversity and destiny. The audience’s applause in reaction to the soaring music and stunning visual and aural presentation, heightened by a bare stage, emotionally charged the performers. Thematically, the cast had an important mandate to share, a cathartic revelation of the sanctity of American values, now on the brink of destruction.

Watching the unfolding of events we cheer for characters like the talented Harlem pianist and composer of ragtime music, Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (the phenomenal Joshua Henry). And we identify with the ingenious, Jewish immigrant Tateh (the endearing Brandon Uranowitz). Tateh must succeed for the sake of his little daughter (Tabitha Lawing), despite their impoverished Latvian background. Likewise, we champion Mother (the superb Caissie Levy), who reveals her decency, kindness and skill, running the house, family and business. She must fill in the gap while her husband (Colin Donnell), goes on a lengthy expedition to the North Pole as a man of the privileged, upper class patriarchy.

The musical also reflects the other side of America’s blood-soaked history, best represented by characters along a continuum. Their misogyny, discrimination and greed often overwhelm, victimize and institutionalize innocents in the name of a just progress. These include tycoons like J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford, and the garden variety racists that brutalize Coalhouse Jr. and his partner Sarah (the fine Nichelle Lewis), in the name of order and security. Finally, to inspire all, the musical includes wily entrepreneurs like Harry Houdini (Rodd Cyrus), social justice advocates like Emma Goldman (the wonderful Shaina Taub), and accepted reformers like Booker T. Washington (John Clay III). All these individuals make up the living fabric of America.

At its most revelatory, Ragtime exposes elements of our present as the continuation of entrenched issues never resolved from our past. Despite our great strides in nuclear fission and quantum computing, retrograde darkness still lurks in the nation’s beating heart, in its violence, in its human rights inequities. Clear-eyed, incisive, DeBessonet’s spare choices about spectacle and design, and her focus on great acting and singing by the leads and ensemble, ground this masterwork.

Ragtime begins with an interesting unexplained entrance: a winsome and beautiful Black male child in period dress frolics across a bare stage. At the conclusion the circle comes to a close and he appears again. We discover who he is and what he symbolizes in a stark, crystallizing moment of elucidation. After the opening number (“Ragtime”), Mother’s adventure as head of her household begins when Father leaves (“Goodbye My Love”). Her helpers include her outspoken, prescient, son Edgar (Nick Barrington), her younger brother (Ben Levi Ross), and her opinionated, crotchety father (Tom Nelis).

However, the peace and serenity of their lives become interrupted when Mother discovers an abandoned baby in her garden. After much deliberation, Mother takes in the infant and traumatized mother, Sarah. Clearly, this startling act of redemption never would have occurred if Father was present. As an assertion of Mother’s right to make her own decisions, her grace becomes a turning point in the lives of the baby’s father, Coalhouse, and his love, Sarah. Apparently, Coalhhouse left Sarah to travel for his career, not knowing she was pregnant. He was pursing his dream of being a singer/composer of the new ragtime music.

By he time Coalhouse searches for Sarah to eventually find and woo her back to him, we note the tribulations of Tateh, who tries to survive using his artistic skills (like Harry Houdini). And we note the moguls of a corrupted capitalism, i.e. Ford, Morgan (“Success”), who Emma Goldman accuses of exploitation. They keep the workers and society oppressed and poor.

Using his charm and daily persistence (“he Courtship,” “New Music,”), Coalhouse wins Sarah back. In a dramatic, dynamic moment, Henry’s Coalhouse sings with emotion, “Sarah, come down to me.” When Lewis’ Sarah descends, their fulfillment together is paradise. The stunning scene like the ones that follow, i.e. “New Music,” and especially Henry and Lewis’ “Wheels of a Dream,” where Coalhouse and Sarah sing to their son about America, are hopeful and heartbreaking. Again, the audience stopped the show with applause and cheers as they periodically did throughout the production.

On the wave of Coalhouse and Sarah’s togetherness and love reunited, we forget the underbelly of a dark America that looms around the corner. It does appears during Father’s reunion with Mother after his lengthy voyage.

Unhappily, Father returns to a household in chaos with Sarah, Coalhouse and the baby under his roof. He can’t imagine what “got into” his wife and makes demeaning remarks about the baby. His conservative, un-Christian-like attitude upsets Mother. She defends her position and replies with demure, feminine instruction. Interestingly, her comment indicates she will not heel to him like the good lap dog she was before he left. As with the other leads, Levy’s performance is unforgettable in its specificity, nuance and authenticity.

Clearly, the characters have made inroads with each other bringing socioeconomic classes together during events when activists like Emma Goldman and Booker T. Washington make their mark and reaffirm equality. As a representative of the wave of immigrants coming to America from other teeming shores, Uranowitz’s Tateh steals our hearts and pings our consciences, thanks to his human, loving portrayal. Despite his bitterness in having to brace against the poverty he came to escape, he tries to overcome his circumstances and with ingenuity and pluck continually perseveres. Uranowitz’s Tateh particularly makes us consider the current government’s cruel, unconstitutional response toward migrants and immigrants today.

Act II answers the conflicts presented in Act I, leaving us with a troubling expose of our country’s heart of darkness. Yet, the musical uplifts bright halos of hope with the return of the adorable Black male child. We discover who he is and understand his mythic symbolism. Also, we learn the fate of the characters, some justly deserved. And the audience leaves remembering the cries of “Bravo” that resounded in their ears for this mind-blowing production.

Ragtime

With music direction by James Moore Ragtime runs 2 hours 45 minutes with one intermission through Jan. 4 at the Vivian Beaumont Theater lct.org.

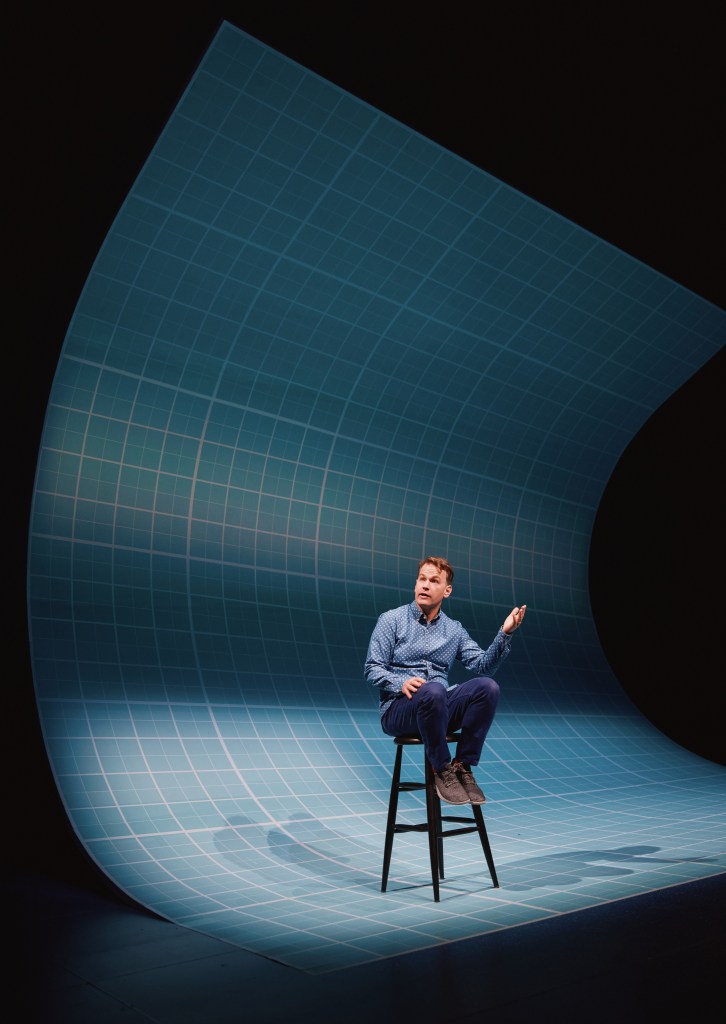

‘Kyoto,’ Climate Science vs. Oil Billionaires’ Profits as the Planet Crisps, Theater Review

Based on events beginning in 1989 leading up to the 1997 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Kyoto, Japan, Joe Murphy and Joe Robrtson’s Kyoto explores the momentous occasion when nations agree to confront climate change. The two-act political thriller is in its US Premiere at the Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse until November 30th. Compressing extensive detail, the playwrights reveal how representatives from 160 nations negotiated the Kyoto Protocol. The Protocol committed first world and emerging nations to limit/reduce greenhouse gasses after setting targets and timetables.

Stephen Daldry and Justin Martin co-direct Kyoto, which enjoyed its world premiere at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon. Due to its continued success, it transferred to London’s West End before debuting to American audiences, who don’t always relate to the ironies and humor in the play (directed at the US). Indeed, the US representative (Kate Burton), and American oil lobbyist Don Pearlman (Stephen Kunken) and the representative of Saudi Arabia (Dariush Kashani) become the objects of humor and frustration. They continually oppose any movement to pin down emissions’ timetables or support decreasing oil production.

The set is a circular conference table where members sit and sometimes interact with the audience. The table serves also as a raised platform for Don Pearlman, placing him above the fray. In its design by Miriam Buether, Pearlman stands at its center and addresses the audience. Variably it becomes a private meeting area where Pearlman speaks with those opposed to any “progress” on emissions. It becomes a setting in his home, and several hotel rooms where he converses with his wife Shirley (Natalie Gold) and others. The co-directors keep the play in the realm of ideas, not material places. In one instance Shirley and Don join Raul Estrada (Jorge Bosch), the Argentinian representative for China, in a rain forest. The fluid, minimal set design forces the audience to keep up with the dialogue cues which indicate setting changes.

The playwrights have chosen the “well-meaning,” slippery lawyer Don Pearlman, as their spokesperson to reveal what happened from 1989 through1997, when nations finally achieved consensus in Kyoto. At the outset Kunken’s disarming oil lobbyist begins by discussing how the Seven Sisters (big oil, i.e, Exxon, Shell, BP) appoint him as their agent provocateur to stall and delay any UN agreement about greenhouse gas emissions.

Like Iago in Othello, Pearlman instructs the audience in his nefarious plans. Though the events happen at lightning speed, Kunken’s Pearlman slow walks us with his wise words and commentary about how to derail progress among the nations.

We become mesmerized as we note how he thwarts the representative countries who have different agendas than big oil conglomerates. Also, by extension we understand why little has been done to effectively curtail global warming. Without particular malice or a sinister tone, Kunken’s Pearlman humanely portrays a man who justifies his mission to support American’s “freedoms” to have a first world economy delivered by fossil fuels. Any change disrupting the oil supply, decreasing fossil fuels and harming profits must be stopped. Truly, Pearlman believes in his job and he believes in doing it well. This makes him and the Big Sisters utterly terrifying and wicked when one stops to consider the consequences.

As we follow along with the various conferences and summits beginning with the 1990 World Climate Conference in Geneva, through the Rio Earth summit, the many rounds of talks with scientists among countries, to 1995 Berlin, the First Conference of the Parties, COP-1, we see Kunken’s Pearlman enact the strategies and philosophies he first discussed with us and his wife Shirley. Without glee, with more than a soupcon of irony, Pearlman, ever the oil lobbyist, proves his genius standing up to various representatives with his knowledge about the process of negotiation, as well as his breadth of knowledge about the subject matter.

He, Burton’s US representative, Kashani’s Saudi Arabian representative for OPEC, and others dismiss the gravitas of what climate scientists have presented about global warming. However, Pearlman’s and others’ delinquence in acknowledging the looming disaster for representatives of low-lying coastal nation states comes to a screeching halt. The representative from Kiribati (Taiana Tully) joins forces with 39 other coastal nations to create a powerful negotiating bloc, The Alliance of Small Island States. They make it clear they will not allow the first world nations to marginalize and destroy them. For it is the first world nations’ oversized pollution that predominately contributes to the polar ice caps melting, and that puts the coastal nations at grave risk.

Thus, the conflict begins in earnest as the first world nations strain against the emerging nations, China having joined the coastal states. Few if any concessions are made for any collective unity as they delay for years, sea levels rise, and time runs out. However, a turning point occurs with the new appointment of Raul Estrada. Bosch’s Estrada eventually bans Pearlman from conferences, despite his being the CEO of the NGO, Climate Council (a blind to get him on the inside). Estrada knows Pearlman’s intent, and Pearlman shows no inclination to change his mission. Their war proceeds as representatives criss-cross the world in jets and add to the increasing emissions they seek to control.

Importantly, the play’s dynamism, pacing and urgency are conveyed by Kunken and Bosch’s performances and the co-directors’ staging and directed momentum. The lead actors who reprise their roles from the London production, have settled into their portrayals. As in real life, the oil lobbyist vs. the Argentinian representative to China smile and joke while warring against each other in a deadly “game” to stop big oil from holding the planet hostage.

Interestingly, the playwrights use the character of Shirley as a foil to soften and humanize Pearlman. However, when she finds out that the Seven Sisters knew about the consequences of global warming since 1959 and have kept this research under wraps, she realizes the wickedness of what her husband attempts. If she gives this information to him will it change his approach to his handlers? How can he live with himself and continue to support big oil knowing what the conglomerates have intentionally done for decades to keep profits flowing while endangering life on the planet?

At its strongest and most profound Kyoto dramatizes the tense political and scientific life and death battles that eventually result in the world’s first legally binding agreement to limit greenhouse gas emissions. That such Sturm und Drang resulted in so little is disappointing. However, in light of today’s international global divisions, to arrive at such a consensus seems miraculous and gives us pause.

Kyoto runs 2 hours 40 minutes with one intermission until Nov. 30 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, lct.org.

‘The Blood Quilt,’ Threading an Ancestral Masterpiece of Hope

The Blood Quilt

In her ambitious layering of the story of four half-sisters who gather to finally lay to rest their recently deceased mother, Katori Hall, with astute direction by Lileana Blain-Cruz, focuses on complex family dynamics, jealousies, misunderstandings and secrets. The confluence of emotions roil the souls of each sister and a teenage niece, paralleling the stormy seas which crash waves onto the setting, Kwemera Island, Georgia. The culmination of fiery anger, pain and sadness releases in the rituals of quilting and the soul healing of family connections in mysticism, dance and song.

By the conclusion of the two-act drama, currently at LCT’s Mitzie E. Newhouse until December 29, we know the fabric of each of the sister’s lives. As a result we thrill with them when they are able to reconcile their inner wounds and cast them into the sea. It is in the waters fronting the small country cabin they call home, where ancestors have been buried in a symbolic tradition that the eldest sister Clementine speaks of with power, “We all came from the water and we all must return.”

The characters are the patchworks that make up the family masterpiece

Much of the beauty of Hall’s drama, laced with comedic elements, comes from her precise characterizations of the disparate sisters who share the same mother but have different fathers. They are the patchworks that make up the last quilted masterpiece that their mother designed and they gather to finish.

Clementine, Gio, Amber

Clementine (Crystal Dickinson), is the eldest, who lives in the incredible ancestral home. Adam Rigg’s set design hums with authenticity, warmth and life. The cabin is decorated with generational family quilts that cover walls and the balcony railing, each colorful, individual, symbolic. Family ownership of the “chic” cabin with the sea in its front yard is in jeopardy because of unpaid taxes which their mother ignored, while keeping her delinquency a secret from her children.

Clementine, who lives there and became caretaker of their dying mother, best knows the rituals of their Jernigan ancestors. A root worker of potions and spells, she speaks Geechee (from their Gullah Geechee heritage), and emotionally archives their legacy, back to the first slave ancestors that lived and worked on the plantations in the area. She is a master of the rituals and celebration of their heritage through quilting which they practice yearly under her direction. This summer when the play opens, the sisters and their niece Zambia (Mirirai), gather together to complete the last quilt their dying mother/grandmother designed, as they symbolically release her to another plane of existence.

Gio (Adrienne C. Moore), is the second oldest, a roughly hewn, hard drinking, Mississippi cop, who is resentful and jealous of her youngest sister Amber (Lauren E. Banks). Gio’s rancor runs deep because of a traumatic, covert incident unbeknownst to Amber but related to Amber’s father that happened when Gio was a teenager. Sensitive to her own misery, burying hurts from her divisive relationship with their mother who abused her, Gio’s moods, aided by alcohol, swing widely as she peppers them with spicey swearing and insults directed mostly at youngest sister Amber.

Amber is the beauty and reputed favorite of their mother because of her accomplishments. She went to an Ivy league college and eventually becomes an entertainment lawyer of means. Because she missed the last three summers of their quilting ritual, and their mother’s funeral service, her estrangement from her sisters and the difference between her lifestyle and theirs is apparent.

Despite Gio and Clementine’s “guilting” her for not coming to the funeral, we discover Amber was emotionally the closest to her mother. She paid for her cancer treatments, phoned her often and even assisted the family after she left the homestead for California. In spite of their geographical and emotional separation, she paid for her sisters’ needs when they asked her, and especially pays for niece Zambia’s tuition in a private school.

Zambia and Cassan

It is Zambia who is the linchpin of the wayward, patchwork family that hangs together by a slender thread as each sister expels her angst and self-recrimination to each other. However, Hall uses Zambia and her mother, the quiet nurse Cassan (Susan Kelechi Watson), who is the closest to Amber, to round out the backstory with Zambia’s questions. Zambia and peacemaker Clementine move along the arc of development which settles upon two issues. How will they pay off the tax liens against the house, and who inherits the quilts, (pricey relics which are cultural artifacts of a rich historical past), the property and the cabin contents?

These questions are answered as Hall unspools each sister’s interior wounds via their relationships, revealing their individual portrait of their complicated, intriguing mother. All clarifies and we are brought to the edge of unresolved personal traumas that threaten to further destroy their lives emotionally, physically, spiritually. However, it is the act of quilting together that we view the whole with the sisters contributing to the corners of the ancestral masterpiece that unifies them with a familial love and redemption from past harm effected by their mother, each other and most importantly themselves.

Mystical elements

Hall’s first act languishes in exposition until the conflicts among the sisters erupt. The details of the quilting process fascinate and are well integrated into the dialogue. The symbolism and metaphor of the stormy souls aligned with the threatening hurricane’s thunder and lightening effected by Jiyoun Chang (lighting design), Palmer Hefferan (sound design), and Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew (projections), mirror how the natural world, material world and spiritual world often collide until there is a movement toward establishing peace and reconciliation.

Blain-Cruz does a smashing job referencing the impact the spiritual plane of existence has upon the material life of the sisters which is sensationally wrought in Act 2 toward the conclusion when they attempt to place the finished quilt on their mother’s bed and a mystical experience occurs. It is then when Zambia becomes the channel between the past spiritual legacy and the present and the pathway toward healing is realized.

The costumes by Montana Lvi Blanco pointedly imbue each of the sisters and Zambia’s changing “trends,” enhancing Hall and Blain-Cruz’s vision of this family to precisely tie in their characters culturally and psychically. Importantly, the ensemble works together to create a family drama with which we can identify and empathize. Their acting is superb. Perhaps the Geechee deserves a translation either in the program or elsewhere. I was benefited by a copy of the script. Vitally, the different language serves to remind the audience of the African diaspora that beleaguered the Jernigan ancestors-slaves, and unified them as they prospered in a hostile, alien world.

The Blood Quilt

See The Blood Quilt, which runs two hours forty-five minutes with one intermission at LCT, the Mitzi E. Newhouse, until December 29th.

,

Theresa Rebeck, Presented by League of Professional Theatre Women at NYPL for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center

Theresa Rebeck. If the name doesn’t sound immediately familiar, chances are you do know Theresa Rebeck’s work from Broadway, off-Broadway, television, films or literature. A prolific writer, she is the most produced female playwright of her generation. Her work is presented throughout the United States and internationally. Her Broadway credits include I Need That (starring Danny DeVito), Bernhardt/Hamlet (starring Janet McTeer), Dead Accounts (starring Norbert Leo Butz), Seminar (starring Alan Rickman), and Mauritius (starring F. Murray Abraham). Her off-Broadway productions are numerous.

It was a pleasure to hear and see her live in an event sponsored by the League of Professional Theatre Women, Monday, June 3, 2024 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center’s Bruno Walter Auditorium. Interviewed by her close friend and producer Robyn Goodman (Avenue Q-Tony Award 2004, In the Heights-Tony Award 2008), Robyn founded Aged In Wood Productions in 2000. Their discussion was taped and is part of LPTW’s Oral History Project to preserve visual records of interviews of august women in the theater. The event was produced by director and producer Ludovica Villar-Hauser. A video of the event can be found in the Library’s TOFT Archive.

For the members of LPTW, Theresa Rebeck needed no introduction. Robyn Goodman began by asking general questions about Rebeck’s early life, and her background tie-ins to themes which often arise in her plays. This brief post focuses on a few salient highlights of the interview.

Born in Ohio, Rebeck grew up in an “ultra Republican, ultra Catholic” world. Receiving a Catholic education throughout, she graduated from Ursuline Academy in 1976 and continued with her Catholic education, graduating from the University of Notre Dame in 1980.

With irony and humor, Rebeck confided, “My parents didn’t want me to go to any East Coast School because they were afraid I’d lose my faith.” She shared that as a child, at times she went on a bus to see theater productions. Even at a young age, she venerated playwrights, thinking them gods. To her, Shakespeare, Moliere, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams were fantastic. She joked that she was already into theater and drama before she got out of grade school.

After Rebeck began acting in earnest at Ursuline Academy, she told her mother “I think I want to be a playwright.” Rebeck got laughs when she joked about her mother’s response, “She turned grey.”

Interestingly, during her freshman year at Notre Dame, Rebeck was invited to a very religious group who was holding a prayer meeting. It was “really spooky,” and the people were “really religious.” Rebeck sensed something “dark and weird going on.” They were speaking in tongues and talking about women being subservient so that everyone “should know their place.” She quipped, “After ten minutes I wanted to go back to my dorm room.” However, she wasn’t sure how to get back.

This was an introduction to members of “People of Praise,” the religious community Supreme Court Justice Amy Cony Barrett has been a member of since birth. “People of Praise,” is associated with the Catholic charismatic renewal movement, but is not formally affiliated with the Catholic Church. Rebeck’s experience at the prayer meeting and listening to the group’s tenets sent her fleeing in the opposite direction. “People of Praise” appears to be unrepresentative of Rebeck’s Catholic upbringing which has well served her life and work.

As a tie-in, Robyn Goodman read a quote from the award-winning playwright Tina Howe (Coastal Disturbances, Pride’s Crossing), who died last year at 85-years old. Howe said of Rebeck that her “Catholic upbringing has had a profound imprint on her work,” and there’s “a moral heart to Theresa.” According to Howe, “She’s a force of nature who always carries her altar with her.”

When Robyn Goodman asked Theresa, “Do you see this in your work?” She responded, “I do.” Rebeck then grounded the history of theater with the idea of faith as an inherent meld. She claimed she is “one of those people” who thinks that the theater is “holy territory.” And she says of herself, “I’m always a person that points out that theater was a religious ceremony.”

In ancient civilizations the dance and tribal ritual and ceremonial presentation had a deep spiritual and religious basis. With the Greeks who allowed even the slaves to take off from work to participate, theater was a celebration of the god Dionysus, and there were annual play festivals and competitions. Rebeck suggested that in various cultures, there was the shaman or priest, and sitting right next to him was the playwright. For Rebeck, “The gathering of people to share stories and identify with the stories is powerful.”

In responding to Robyn Goodman’s question about her transformation to professional theater, Rebeck mentioned her first production was Spike Heels (1993), that Goodman produced at Second Stage Theater. It starred Kevin Bacon, Tony Goldwyn, Saundra Santiago and the great Julie White. “My husband was in it,” quipped Rebeck. Theresa is married to Jess Lynn, and together they have two children.

Goodman asked if the production and notoriety changed her life, especially the good reviews. Rebeck suggests that with the critics peppering her with questions, “It was like watching all the senators grilling Anita Hill.” One of the questions they asked, was, “Are you going to write a book?” Frank Rich compared Spike Heels to the film Pillow Talk. According to Rich, Kevin Bacon was Gig Young, etc.

Four months later, David Mamet’s Oleanna, which premiered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, appeared off- Broadway at the Orpheum Theater. Frank Rich reviewed it and Rebeck noted Rich’s review. He commented that after the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas fiasco on Capitol Hill, “finally someone wrote a play about sexual harassment.” Rebeck’s response was tellingly frustrated. She shared her feelings about his comment. “Hey! You saw a play about sexual harassment written by a women and you didn’t notice.”

It was “a different time,” Rebeck said, as she discussed how she reacted to the male/female power issues. “You go along with it, get mad when you go home and try to discuss it, and you’re incoherent.” With Rich’s comment about Oleanna, Rebeck says,”I thought, ‘Come on, this isn’t about sexual harassment. This is a women lying about sexual harassment.'” Rebeck affirmed with Goodman that women were fighting for their place and stature at the time, so it was “very important to produce plays like that.” Rebeck suggested, “I was way ahead of my time,” which received an appropriate laugh.

Goodman pointed out another quote about Rebeck’s writing in that she often writes about “betrayal, treason and poor behavior, a lot of poor behavior.” To that Theresa agreed that many playwrights write about “poor behavior.” Goodman added that Rebeck also writes about class and power shifts.

Rebeck discussed her experiences with productions on Broadway and off-Broadway. In fact, she suggested that she began directing because after the effort and time spent writing a play, she got tired of the release process, after her initial involvement with the production. She went to the table reads, heard design presentations and answered questions people asked. Then came the “thank yous” and she would leave. Rebeck didn’t want to be at the side of “the main event.” She wanted total involvement.

She enjoyed working on Dig, which she also directed and which received wonderful reviews. “I’m so proud of it. It was a good experience.” It is important to Rebeck that the creators have work that they can claim as their own. She enjoys working collaboratively when people are respectful.

Goodman and Rebeck appear to have a shared view of how people negotiate successfully in the “real world.” They negotiate with a sense of morality. Goodman shared the quote which political parties, especially the Trump MAGA Party, eschew as anathema. “If you make the truth your friend, it can’t come and eat you alive.” Rebeck and Goodman agree that a clear, moral point of view in plays, musicals and literature is vital.

Theresa suggested that her alma mater Brandeis University also grounded her toward presenting a clear, moral point of view in her work. She received her three graduate degrees from Brandeis: her MA in English in 1983, a MFA in Playwriting in 1986, and a PhD in Victorian era melodrama in 1989. Fittingly, Rebeck pointed out, that on the seal of Brandeis University are the words, “Truth even unto its innermost parts.” The university president decided to surround the shield on the seal with the quote about truth which is from Psalm 51. Rebeck noted that she recognized the seal on the podium (though it wasn’t clear at that point that it was Brandeis), hearing/seeing a clip of Ken Burns deliver his trenchant Keynote Address to Brandeis University’s 2024 undergraduate class during the 73rd Commencement Exercises. If you haven’t heard any of his speech, you can find it on YouTube. It is definitive and acute.

Rebeck affirms that “writing plays is about people” in the hope to understand “human brilliance and failure.” Of course at times there’s “political content.” However, at the heart it’s about people and human behavior.

In responding to Goodman’s question related to critics, Rebeck agreed that sometimes reviews are devastating and that her husband goes through the process with her. She mentioned that there can be five wonderful or enlightening critiques, and then there is the “crazy” review which is off kilter and seemingly out of nowhere, and people are “foaming at the mouth.” Sometimes, there is that one review while other critics and audiences love the work.

At one point Rebeck thought, “Why do they hate me?” Then, she realized if there’s one outlier, then there isn’t coherence. She mentioned that for a long time people only cared about and quoted the “paper of record.” Of course the irony was that there were many different critics and opinions. The diverse voices and viewpoints are exciting and especially vital for our time. That one opinion held sway and could make or break a play was “damaging to the psyche of the community.” She affirmed, “Now, it’s less dire.”

Rebeck spoke of an incident with a young producer who acted as if there was only one paper that mattered, historically, the “paper of record.” This individual said, based on one review, “Well, the reviews were bad.” Rebeck gave them a reality check. She said that a producer should never act like there is one reviewer who speaks for all critics. To obsess about one review is to bury oneself in negativity and recriminations. She told the producer, “Don’t do that!”

Indeed, Rebeck’s point is well taken. Historically, other critics bought into the prestige factor of “the paper of record,” denigrating their own voices and viewpoints, and bowing to the one review that allegedly spoke for all critics. In this day of book bannings, culture wars and rewriting history, such an approach is tantamount to critics mentally censoring themselves as inferiors. If there is a consensus about a play, that speaks volumes. One “determination” by one critic, regardless of how much he or she is paid, shouldn’t be the “word from on high” that the critics, theater professionals or the public “should” listen to and take to heart.

Rebeck and Goodman are expanding their winning teamwork. They’ve joined together on the musical Working Girl, based on the titular1988 Twentieth Century Fox motion picture written by Kevin Wade. Aimed for Broadway, the musical is presented by special arrangement with Buena Vista Theatrical. Writing the book, Rebeck discussed how she loves working with Tony-winning, composer-lyricist Cyndi Lauper (Kinky Boots), who is writing the score. Tony winner Christopher Ashley (Come From Away) is directing. Producers include Goodman and Josh Fiedler of Aged in Wood Productions, and Kumiko Yoshii.

Rebeck created Smash for NBC and briefly discussed a few highs and lows of working on the showbiz dramatic series. She liked Stephen Spielberg. Since Smash, she has been especially enamored of musical theater. Working Girl is a project that involves collaboration. To have to write a play singularly and then give it to a composer and lyricist is something Rebeck wasn’t interested in doing. She and the team are reimagining and updating the classic. It’s an exciting approach because it also emphasizes women working together and supporting each other on their “climb to the top.” With the political climate as it is, the musical is profoundly important.

One of the themes of the evening was that especially after COVID-19, theater has changed. Theaters around the country are in deep financial trouble. Robyn Goodman suggested that Broadway has gotten out of hand. The business is completely different than what it was two decades ago. Now, to mount a production viably, it costs $25 million dollars. It’s all about the money and finding backers.

As for budding playwrights, Rebeck advised that festivals are a good venue as a place to begin and get noticed. Indeed, 10 minute play festivals allow the creative team to put on “a beautiful event” for little or no money. One can even write a short one-act play and submit it to a one-act play festival. This is a boon for the playwright, who needs to learn how the process works and see the audience’s response to the play. That is an imperative for beginning playwrights.

Rebeck’s plays are published by Smith and Kraus as Theresa Rebeck: Complete Plays, Volumes I, II, III, IV and V. Acting editions are available from Samuel French or Playscripts. For a complete listing of all of her work you can find Theresa Rebeck on her website: https://www.theresarebeck.com/ Robyn Goodman’s website is https://www.agedinwood.com/about

Visit The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, the Library’s TOFT Archive to see the digital recording of the evening. For more information about the TOFT Archives, see this link. https://www.nypl.org/locations/lpa/theatre-film-and-tape-archive To learn more about LPTW, check out their website. https://www.theatrewomen.org/

‘Uncle Vanya,’ Steve Carell in a Superb Update of Timeless Chekhov

A favorite of Anton Chekhov fans is Uncle Vanya because it combines organic comedy and tragedy emerging from mundane, static situations, intricate, suppressed characters and their off-balanced, mired-down relationships. Playwright Heidi Schreck (What the Constitution Means to Me), has modernized Vanya enhancing the elements that make Chekhov’s immutable work relevant for us today. Lila Neugebauer’s direction stages Schreck’s Chekhov update with nuance and singularity to make for a stunning premiere of this classic at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont in a limited run until June 16th.

With a celebrated cast and beautifully shepherded ensemble by the director, we watch as the events unfold and move nowhere, except within the souls of each of the characters who climb mountains of elation, fury, depression and despair by the conclusion of this two act tragicomedy.

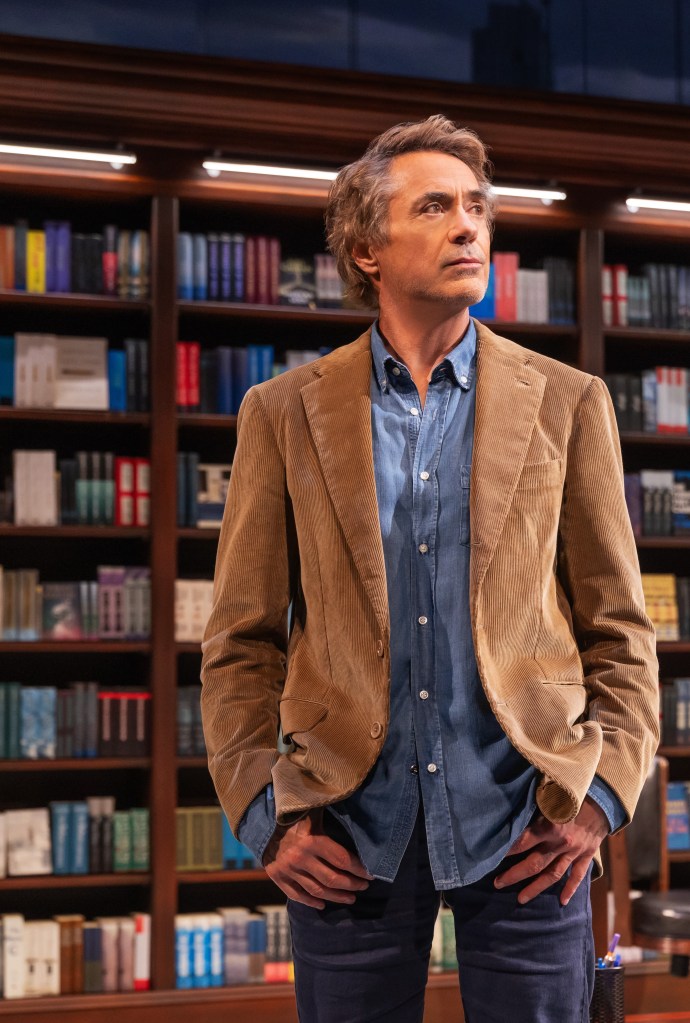

Schreck has threaded Chekhov’s genius characterizations with dialogue updates that are streamlined for clarity, yet allow for the ironies and sarcasm to penetrate. At the top of the play Steve Carell’s Vanya is hysterical as he expresses his emotional doldrums at the bottom of a whirlpool of chaos which has arrived in the form of his brother-in-law, Professor Alexander (the pompous, self-important Alfred Molina in a spot-on portrayal), and Alexander’s beautiful, self-absorbed, younger-by-decades wife Elena (Anika Noni Rose). Also present is the vibrant, ironic, self-deprecating, overworked Dr. Astrov (William Jackson Harper), a friend who visits often and owns a neighboring estate.

During the course of the first act, we are witness to the interior feelings and emotions of all the characters who in one way or another are bored, depressed, miserable and disgusted with themselves. Vanya is enraged that he has taken care of Alexander’s lifestyle, even after his sister died in deference to his mother, Maria (Jayne Houdyshell). He is particularly enraged that he believed with is mother that Alexander was a “brilliant” art critic who deserved to be feted, petted and over credited with praise when he lived in the city.

Having clunked past his prime as an old man, Alexander has been fired because no one wants to read his work. He and Elena have run out of money and are forced to stay in the family’s country estate with Vanya and Sonia, Alexander’s daughter (the poignant, heartfelt Alison PIll), away from the limelight which shines on Alexander no more. Seeing Alexander in this new belittlement, though he orders around everyone in the family, who must wait on him hand and foot, Vanya is humiliated with his own self-betrayal. He didn’t realize that Alexander was a blowhard who duped and enslaved him to labor on the farm to supporting his high life, while he pursued his “important” writing. Vanya and Sonia labor diligently to make sure the farm is able to support the family, though it has been a difficult task that recently Vanya has grown to regret. He questions why he wasted his years on a man unworthy of his time and effort, a fraud who knows little about art.

Likewise, Astrov questions his own position as a doctor, admitting to Marina (Mia Katigbak), that he feels responsible for not being able to help a young man killed in an accident. To round out the “les miserables,” Alexander is upset that he is an old man who is growing more decrepit by the minute as he endures believing his young, beautiful wife despises him. Despite his upset, Alexander expects to be waited on by his brother-in-law, mother-in-law and in short, everyone on the estate, which he has come to think is his, by virtue of his wanting it. Though the estate has been bequeathed to his daughter Sonia by Vanya’s sister, his first wife, Alexander and Elena find the quiet life in the country unbearable.

As they take up space and upturn the normal routine of the farm, Elena has been the rarefied creature who has disturbed the molecules of complacency in the lives of Vanya, Sonia and Astrov. Her beauty is shattering. Sonia hates her stepmother, and both Vanya and Astrov fall in love and lust with her. As a result, their former activities bore them; they cannot function with satisfaction, and have fallen distract with want, craving the impossible, Elena’s love. Alexander fears losing her, but realizes if he plays the victim and harps on his own weaknesses of old age, as distasteful as he is, Elena is moral enough to attend to him, though she is bored and loathes him in the process.

The situation is fraught with problems, hatreds, regrets, upsets and soul turmoil, which Schreck has stirred following Chekhov’s dynamic. Thus, Carell’s Vanya and Harper’s Astrov are humorous in their self-loathing as is the arrogant Alexander and vapid Elena who Sonia suggests can end her boredom by helping them on the farm. Of course, work is not something Elena does, which answers why she has married Alexander and both have been the parasites who have sucked the lifeblood of Vanya and Sonia, as they labor for their “betters,” who are actually inferior, ignoble and selfish.

To complicate the situation, Sonia is desperately in love with Astrov, who can only see Elena who is attracted to him. However, Elena is afraid to carry out the possibility of their affair. Instead, she destroys any notion that Sonia has of being with Astrov by ferreting out Astrov’s feelings for Sonia which tumble out as feelings for Elena and a forbidden, hypocritical kiss which Vanya sees and adds to his rage at Elena’s self-righteousness and martyred morality. When Elena tells Sonia that Astrov doesn’t love her, Sonia is heartbroken. It is Pill’s shining moment and everyone who has experienced unrequited love empathizes with her devastation.

When Alexander expresses his plans to sell the estate and take the proceeds to live in the city in a greater comfort and elegance, Carell’s Vanya excoriates Alexander and speaks truth to power. He finally clarifies his disgust for the craven and selfish Alexander, despite Maria’s belief that Alexander is a great man, not the fraud Vanya says he is.

It is a gonzo moment and Carell draws our empathy for Vanya who attempts to expiate his rage, not through understanding how he is responsible for being a dishrag to Alexander, but through manslaughter. The scene is brilliantly staged by Neugebauer and is both humorous and tragic. The denouement happens quickly afterward, as each of the characters turns to their own isolated troubles with no clear resolution of peace or reconciliation with each other.

The ensemble are terrific and the actors are able to tease out the authenticity of their characters so that each is distinct, identifiable and memorable. Naturally, Carell’s Vanya is sympathetic as is Pill’s heartsick Sonia, for they nobly uphold the ethic that work is a kind of redemption in itself, if dreams can never come true. We appreciate Harper’s Astrov in his love of growing forests and his understanding of the extent to which the forests that he plants will bring sustenance to the planet, if even to mitigate only somewhat the society’s encroaching destructiveness. Even Katigbak’s Marina and Sonia’s godfather Waffles (the excellent Jonathan Hadary), are admirable in their ironic stoicism and ability to attempt to lighten the load of the others and not complain.

Finally, as the foils Molina’s Alexander and Noni Rose’s Elena are unredeemable. It is fitting that they leave and perhaps will never return again. The chaos, misery, dislocation and confusion they leave in their wake (including the somewhat adoring fog of Houdyshell’s Maria), are swallowed up by the beautiful countryside and the passion to keep the estate functioning which Sonia and Vanya hope to achieve in peace. Vanya, for now, has thwarted Alexander, by terrorizing Alexander into obeying him in a language (threatening his life), he understands. For this we applaud Vanya.

When Alexander and Elena leave, the disruption has ended and they take their drama and chaos with them. It is as if they were never there. As Vanya and Sonia handle the estate’s paperwork, which they’ve neglected having to answer Alexander’s every need, the verities of truth, honor, nobility and sacrifice are uplifted while they work in silence, and peace is restored to the estate, though they must suffer in not achieving the desires of their lives.

Neugebauer and Schreck have collaborated to create a fine version of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya that will remain in our hearts because of the simplicity and clarity with which this update has been rendered. Thanks go to the creative team. Mimi Lien’s set design functions expansively to suggest the various rooms of the estate, the garden and hovering forest in the background. A decorative sliding divider which separates the house from the forest and allows us to look out onto the forest and woods beyond (a projection), symbolizes the division between the natural and the artificial worlds which influence and symbolize the characters and what they value.

Vanya and the immediate family take their comforts from the earth and nature as does Astrov. Alexander and Elena have forgotten it, finding no solace in the beautiful surroundings and quiet, rural lifestyle which they find boring because they prefer chaos and the frenetic atmosphere of society. Essentially they are soul damaged and need the distractions they’ve become used to when Alexander was famous and the life of the party before he got tiresome and old and disgusting in the eyes of Elena and those who fired him..

The projection of trees that expands entirely across the stage in the first act is a superb representation of what is immutable and must be preserved as Astrov works to preserve. The forest of trees which is the backdrop of the garden, sometimes sway in the wind. The rustling leaves foreshadow the thunder storm which throws rain into the garden/onstage. The storm symbolizes the storm brewing in Uncle Vanya about Alexander, and emotionally manifests when Alexander suggests they sell the estate to fulfill his personal agenda.

During the intermission every puddle and water droplet is sopped up by the tech crew. Kudos to Lap Chi Chu & Elizabeth Harper for their lighting design and Mikhail Fiksel & Beth Lake for their sound design which bring the symbolism and reality of the storm home.

The modern costumes by Kaye Voyce are character defining. Elena’s extremely tight knit, brightly colored, clingy dresses are eye candy for her admirers as she intends them to be to attract their attention, then pretend she doesn’t want it. Of course she is the leisurely swan while Sonia is the ugly duckling in work clothing, Grandmother Maria dresses like the “hippie radical feminist” that she is, and Marina is in a schmatta as the servant who cooks and cleans. Here, it is easy for Elena to shine; there is no competition.

Vanya looks frumpy and uncaring of himself. This reflects his depression and lack of confidence, while Molina’s Alexander is dressed in the heat like a peacock with a scarf, cane and hat and cream-colored suit when we first see him. Astrov is in his doctor’s uniform, utilitarian, purposeful, then changes to more relaxed clothing. The costumes are one more example of the perfection of Neugebauer’s vision and direction of her team.

Uncle Vanya is an incredible play and this update does Chekhov justice. It is a must-see for Schreck’s script clarity, the actors seamless interactions and the creative teamwork which elevates Chekhov’s view of humanity with hope, sorrow and love in his characterizations, especially of Vanya.

Uncle Vanya runs two hours twenty-five minutes including one intermission, Lincoln Center Theater at the Vivian Beaumont. https://www.lct.org/shows/uncle-vanya/whos-who/

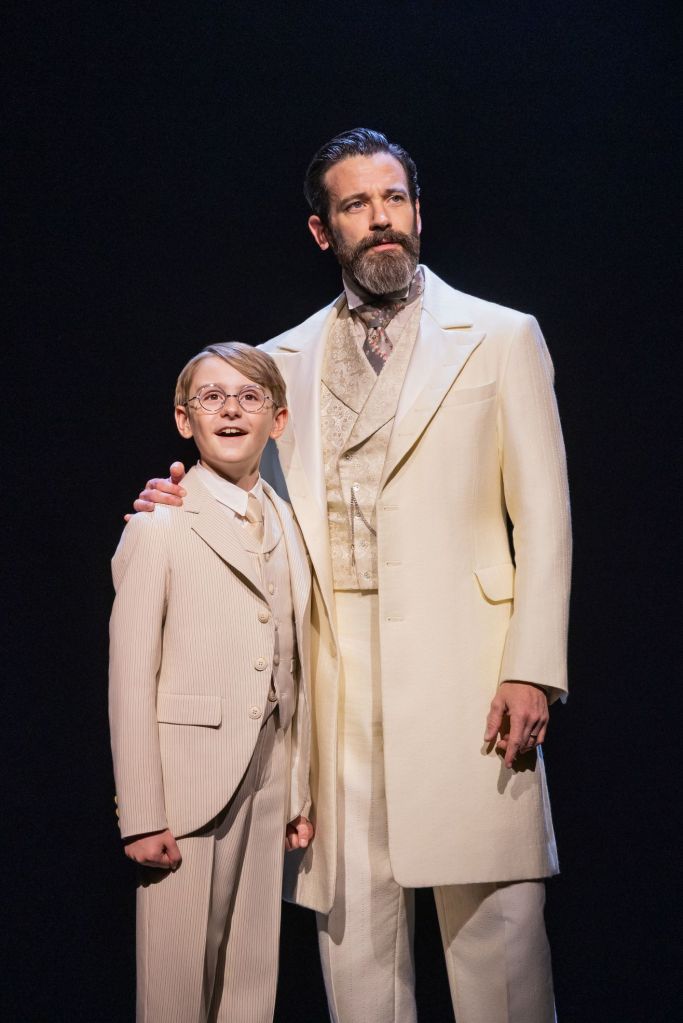

‘Notre Dame de Paris’ at Lincoln Center is Just Smashing!

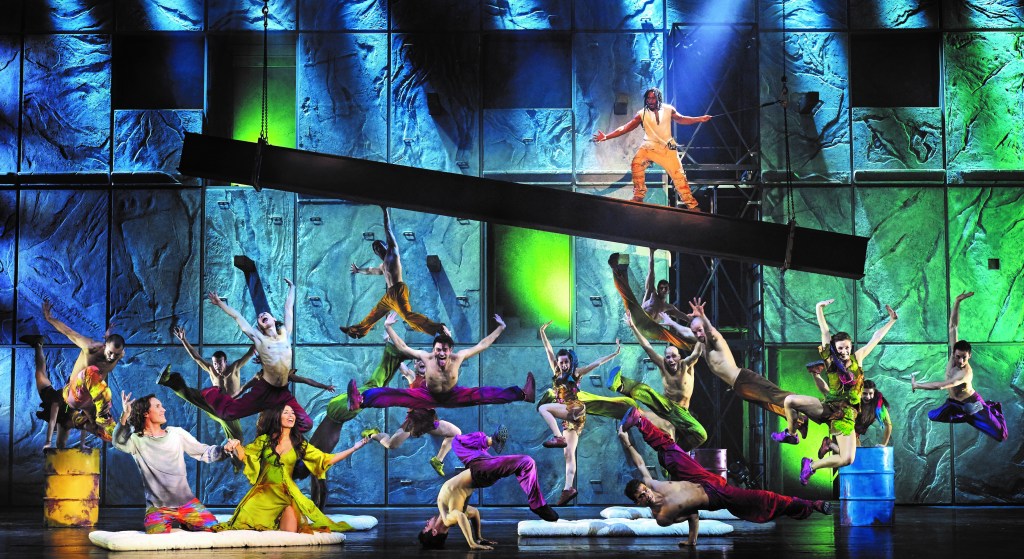

For the first time in its twenty-four year history since its premiere in Paris, France in 1998, Notre Dame de Paris makes its New York City debut. The acclaimed musical spectacular has toured internationally, featuring successful productions in Canada, Italy, Lebanon, Singapore, Japan, Turkey and China. Performed in 23 countries and translated into nine languages, accumulating an enthusiastic 15 million spectators worldwide, the production at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center premiered on the 13th of July and runs through, Sunday, 24 July.

Notre Dame de Paris extravagantly directed by Gilles Maheu is a transcendent, opera-styled musical rendering of Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Based on Hugo’s monumental work of passion, love, lust, jealousy, cultural transformation, racism, classism and misogyny, the Notre Dame cathedral is the centerpiece around which most of the whirling action of this spectacle takes place.

It is there in front of the massive stones being set in the opening scene, Gingoire (the exceptional Gian Marco Schiaretti), introduces the cathedral in “Le Temps des cathedrals.” In the square in front of Notre Dame we meet the stratified economic classes of Paris, i.e. the undocumented immigrants who seek asylum and sleep in front of the cathedral. It is from there that the action leads out to the streets of Paris, beyond and back again. Thus, throughout, the cathedral becomes a moral, spiritual, ironic presence. It signifies a religion that encourages brotherly/sisterly love but rarely lives up to its aspirations in the actions of the clerics and the classist citizenry we meet.

Luc Plamondon’s lyrics propel the arc of development in composer Richard Cocciante’s sung-through, pop-rock, people’s opera. Generally, the almost three hour production follows Hugo’s novel, omitting minor characters that lightly impact the plot of the original work.

Cocciante’s florid music and Plamondon’s pop-rock lyrics comprise a total of 51 separate songs. Many of these are lyrical ballads describing the principal characters’ feelings about the situations they find themselves in. Others are powerful anthems, like the gorgeous signature song “La Temps des cathedrals,” and “Florence,” when Frollo and Gingoire discuss how Gutenberg’s printing press and Luther’s 95 Thesis will kill the old Paris and the cathedral as they make way for the new in the roiling undercurrents of society, as immigrants flood the city bringing with them new trends and transformations as they swell the population of Paris.

Live musicians accompany pre-recorded tracks performed in French with English surtitles provided on two screens to the left and right of the stage. Unlike opera the performers’ voices are electronically enhanced. At times one focuses more on sound than the quality of the performance. But all the principals have gorgeous voices and their talents are memorable and exquisite for this amazing, iconic musical epic.

There are seven principal characters who represent the inner and outer circles of the populace. These include Gingoire the poet and narrator who codifies the settings around Paris and introduces the characters and situations. Gingoire is the herald who announces the shifts in action. He moves among the Parisians and is a friend of those who have status like Frollo the Archdeacon of Notre Dame (the superb Daniel Lavoie). Floating among the undocumented immigrants Gingoire gets to know Clopin and Esmeralda in Act I, proving he is no respecter of classes and persons. In Act II he informs Clopin (Jay), the leader of the undocumented immigrants, that Esmeralda is in prison. Gringoire is present to understand how the immigrants try to come to Esmeralda’s aid to no avail. Her gender, her striking beauty, her class and above all her destiny, damns her.

In his movements around the city when Gringoire stumbles into the wretched Court of Miracles, it is then he becomes acquainted with Clopin (Jay) and Esmeralda (Hiba Tawaji). Situated outside the city walls, the ironically named court is the den of the impoverished undocumented, and the city’s outcasts. Clopin has created his own set of rules for the Court of Miracles that those who live there must follow. Kindly, he protects teenager Esmeralda allowing her to take refuge in the Court. Like a brother, he warns her against being too trusting of men.

Emeralda, a Bohemian from Spain is the catalyst who moves the action and emblazons the passions of men to love, hate or exploit her. As she prettily dances in the square, she unfortunately attracts the attention of the men of power, Archdeacon Frollo and Phoebus (Yvan Pedneault), captain of the King’s cavalry. They both want her. She becomes the vulnerable pawn who they attempt to exploit, abuse, then expediently toss away. Her youth, innocence and beauty are the fatal instruments that contribute to effecting her demise as the men wantonly pursue her sexual affections. The only one whose love she returns is Phoebus. However, he is pledged to marry a woman of consequence and class, Fleur-de-Lys (Emma Lépine). Eventually, he chooses a life of unhappiness with Fleur-de Lys because it is one which satisfies his need for stature and security though it is empty of love and pleasure.

Quasimodo, the lame, hunchback bell ringer also notes Esmeralda’s beauty and unhappily contrasts himself with her. She is someone he wishes to love but he knows it would be an impossibility. To confirm his “celebrity” as the most externally loathsome of all creatures, he is crowned “The King of Fools” in the songs “La Fête des fous” and “Le Pape des fous.”

Staged as frenetic, wildly antic numbers that involve the large cast, we watch as five acrobats, two breakers, and sixteen dancers, all of them marvelously talented, hurl themselves across the stage, spin and gyrate. These two numbers are visually exciting as most of the songs which combine dance are. Importantly, they create empathy, revealing how Quasimodo is treated by a world that worships physical loveliness and eschews deformity. However, Esmeralda has a kind heart and wishes that all humanity could become like brothers/sisters with no boundaries. She makes a connection of consciousness with him. Quasimodo becomes Esmeralda’s chief protector after she gives him a drink during his punishment for attempting to kidnap her on Frollo’s orders.

Quasimodo is Frollo’s puppet, having been raised by the cleric when he was orphaned as a baby. Whatever Frollo says to do he does because he is indebted to him. In the powerful and beautiful “Belle,” Frollo, Quasimodo and Phoebus secretly reveal their love of Esmeralda, claiming her for themselves. However, only Quasimodo loves her unselfishly without seeking to take anything from her, unlike Frollo and Phoebus.

The conflict intensifies when Frollo, unable to deal with his unholy, sexual feelings for Esmeralda attempts to take her for himself in an act of self-destruction and sinfulness, “Tu vas me détruire.” He has her falsely arrested for killing Phoebus, a lie. He knows she loves Phoebus and his jealousy enrages and victimizes him. His desire for her turns to hatred. Frollo visits her in jail where he propositions her to give herself to him and reclaim her life. Frollo has given up his identity and holiness embracing the hypocrisy of his lust and murderous jealousy of Phoebus. He is Archdeacon only in his robes and title. For her part Esmeralda realizes she fulfills her destiny loving Phoebus and sacrificing her life.

Daniel Lavoie who originated the role of Frollo masterfully reveals the character’s self torment, rage and incredible hurt, throwing off any mantel of faith to possess Esmeralda. In his portrayal Lavoie reveals Frollo’s doom as he blasphemes his religion, all in the shadows of Notre Dame. Though Quasimodo realizes Frollo’s malevolence and impulse to hang Esmeralda, there is little he can do to stop Frollo’s actions. Only after she hangs does he answer Frollo’s wickedness.

Notre Dame de Paris is a fitting title for this incredible production. The cathedral represents the chief moral and structural backdrop of the themes, characters and conflicts that reveal how religion, unless lived spiritually is a damnation. Also, it is upon this backdrop that we understand how fate and destiny unravel for Esmeralda, Frollo, Quasimodo and Phoebus, as they struggle to find but ultimately lose their place in the dynamically changing Paris of 1482.

This version is incredibly current in its attention to the plight of the undocumented immigrants, a situation that will only worsen globally with climate change and Putin’s War in Ukraine. Also, the production reveals the plight of women in the hands of men who have the power to abuse and destroy them. Hugo’s attention to humanity and the incompetence of religion to deny decency and hope to individuals who are stateless, classless and viewed by citizens as lower than worms is all the more striking because the situation still abides. One asks the question does anything change except the progress of science and technology when it delivers monetarily? Only the gargoyles can answer. Since this production was first mounted in 1998, progress reveals how much our humanity has deteriorated and even the cathedral itself has suffered a cataclysm that will never return it to its former ancient glory.

Kudos to the the director Gilles Maheu whose vision was faithfully melded in the staging, choreography by Martino Müller, set design by Christian Rätz, costume design by Caroline Van Assche, lighting design by Alain Lortie and hair and wig design by Sébastien Quinet. Praise also goes to musical director Matthew Brind and surtitles by Jeremy Sams. The production takes one’s breath away and every song is exceptionally beautiful in French and poetically lyrical if one understands the language.

Though Notre Dame de Paris has finished its New York City run you may catch it elsewhere as it is on tour and heading to Canada. Check out their various websites: https://nac-cna.ca/en/event/20729 http://www.avenircentre.com/ and look for it to return to the U.S. and perhaps New York City in the future.

‘Epiphany,’ Subtle, Understated, Irony, a Review

At the outset of Epiphany by Brian Watkins, directed by Tyne Rafaeli, we hear a thunderous, rumbling, like a breaking apart of the ethers, that signifies something momentous may occur. After all on one level, the title references the traditional yearly celebration after Christmas when the Magi acknowledged the divinity of the Christ child. On the other hand certainly, the play’s themes will stimulate us to have an “epiphany” about our own lives. As we sit in the dark theater, we wait to be moved by what may be some great stirring.

In the shaking and weird roaring noise that lasts a few seconds at the top of the play, we have a chance to peruse Morkan’s (Marylouise Burke) expansive, circular, den-dining room in her idyllic, barn-like mansion somewhere in the woods near a river. The place has been renovated and repainted, long-time friend Ames (the wonderful Jonathan Hadary) reveals during the course of the evening. Two large floor to ceiling windows are set equidistant to the right and left of the central staircase. They look out on an immense tangle of dark, surreal tree limbs and bushes upon which snow falls but never sticks. John Lee Beatty’s set is a magnificent throwback to a former Americana of dark, rich, wood paneled loveliness whose central point is three staircases: one short leap of stairs from the entrance opening onto the main floor, and two massive staircases leading to the second story presumably of bedrooms and a bathroom with a novel Japanese toilet that Freddy (C.J. Wilson) admires.

On January 6th, each year millions celebrate the Epiphany world-wide but not in America, the dinner hostess Morkan informs all her company after they have arrived. She has invited her friends and grand nephew Gabriel (name reference-the angelic messenger who announced the Christ child’s birth) to this unique January 6th dinner party for a celebration of the Epiphany during which her grandnephew will officiate. She doesn’t quite remember the significance of the day but thought it appropriate to have a gathering of friends she hasn’t seen for a long while to celebrate because the date is located in the dark loneliness of winter, after Christmas and the season of light.

However, Gabriel lets his aunt down. He can’t make the party, so he can’t officiate and Morkan is left to be mistress of ceremonies on this occasion, that no one in the group has celebrated before or even understands. However, she tries to guide the festivities and does so humorously in fits and starts. Interestingly, Gabriel makes up for his absence by sending his partner Aran (Carmen Zilles) the symbolic stranger (think “The Dead” by James Joyce that Watkins’ set up suggests). She is the only one to be able to relay something about Epiphany, manifestly suggesting its true meaning of the Magi bringing gifts to the Christ child, and referencing a layered meaning: the confluence of the divine in humanity by the play’s end.

The festivities that Morkan planned, whose order has been sent in an attachment to her friends that no one read, happen with the quirky turn of her mind. As she tries to remember them, she informs the guests that remembering is becoming harder because of her lack of focus. Nevertheless, she takes charge and this lovely evening among individuals not initially friends who become friends unfolds with beauty and poignancy encouraged by Morkan’s generous hospitality, openness and humanity (in divinity).

Watkins via director Rafaeli’s vision, cleverly, ironically misleads us throughout, beginning with the early fanfare to expect “greatness.” However, Watkins sidelines our anticipation for “the momentous” with the humorous interactions of the guests. We listen to Morkan’s prating about why she must confiscate their cell phones to everyone’s horror. To move the “epiphany celebration” along, she suggests they sing the related song. No one knows it.

We relax into the off handed conversational comments as guests help themselves to alcohol. We watch the very visual piano interpretation of a piece by Kelly (Heather Burns) which is a hysterically cacophonous substitute for the song of epiphany that no one learned. And to honor the celebration, Sam (Omar Metwally) brings out a galette des rois he has prepared, explaining someone must go under the table to call out who gets the first slice. Additionally, Sam shares that all must look for the surprise inside which if they find it, means they are the King or Queen of the celebration. Ames volunteers to go under the table and call out a name. And then we forget about him when Sam and Aran discuss the finer points of empiricism and the ineffable which are relational to the miracle of the epiphany.

And just when we think the play is about to take a really profound turn, Morkan shuffles up the cards and calls out “Who wants a slice of the galette.?” What occurs is the comical high point point of the production, seamlessly directed by Rafaeli and enacted by Jonathan Hadary’s Ames, Marylouise Burke’s Morkan and the others, like Loren (Colby Minifie) who stem the bleeding and help quell the chaos.

By the time the food arrives on the table, we understand that something fascinating is going on. The shining moments of meaning that signify joy that the tradition encourages should happen happen. Indeed, much happens in the apparent little insignificances. Individuals listen and respond to each other and enjoy each other. The moments move serendipitously during the evening of this diverse, wacky group of individuals who have been divorced from their phones by Morkan so they can relate to each other in a live, spontaneous interactive dynamic. That alone is miraculous for her to insist upon, and of course, grandly funny.

As the food is passed around and they comment the goose is dark, toward the end of the meal the subject turns into the years one has yet to live. And as Ames recalls a humorous story, at the end of it Morkan’s revelations about her sister abruptly emerge. They are still a shock to her and they are a shock to her friends who begin to understand Morkan’s comments about lack of focus and her need for company during the darkest time of the year.

Nevertheless, continuing the celebratory spirit, Morkan, ever the thoughtful hostess brings out the dessert which she insists they eat. And it is during the dessert, she explains the devastation she has been feeling, the need of forgiving herself and the importance of forgiveness in her life, in everyone’s lives. These feelings which she shares are made all the more real for herself and her friends in their public revelation. Her deeply intimate confession touches their hearts and is codified by Aran as an “epiphany.” The theme of revelation coalesces into the symbolism of the miraculous that Morkan seeks. And the recognition of her friends to celebrate the Epiphany the following year as a tradition indicates that they seek that divine in humanity in the sharing of community. The last moments are particularly heart wrenching.

This is one to see for the terrific ensemble work and smart, smooth direction by Rafaeli, the sets, humorous moments and atmospheric tone poetry suggested by the lighting among other elements. Kudos to Beatty for his sets, Montana Levi Blanco for costumes, Isabella Byrd for lighting, Daniel Kluger for original music and sound. Epiphany runs with no intermission and ends July 23rd. Don’t miss it. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.lct.org/shows/epiphany/

‘The Skin of Our Teeth,’ a Zany Exploration of the Fate of Humanity at Lincoln Center

Thorton Wilder’s Pulitizer Prize winning The Skin of Our Teeth currently in revival at Lincoln Center’s Viviane Beaumont, presents the fate of the human race in three segments when the human family represented by the Antrobuses (Greek for man or human), faces extinction. The first debacle is the ice age; the second is the great deluge; the third is a seven years war. The play leaves off in uncertainty for surely humanity will continue to face threats of extermination and will continue to shake these off, repair itself and scientifically progress to greater heights and lower depths in its struggle to survive as a species. Though Wilder leaves this conclusion uncertain through the character of Sabina (the vibrant and versatile Gabby Beans), the very fact that the characters make it as far as they do is a witness to human resilience and tenacity.

The production, one of spectacle and moment, whimsy and humor is acutely directed by Lileana Blain-Cruz for maximum effect. It succeeds in various instances, to be poignant and profound as the Antrobus family (James Vincent Meredith-Dad, Roslyn Ruff-Mom, Julian Robertson-Henry, Paige Gilbert-Gladys) and their maid Sabina (Gabby Beans), the narrator who breaks the fourth wall to address the audience, claw their way through history to survive. These “every men” and “every women” archetypes experience representative cataclysms, all the while confronting the questions about the human race and their place in history until the end of time.

Though Wilder references Bible figures like Cain, suggests Adam, Eve and Lilith (Lily Sabina), and the disasters that have foundations in tribal religious mythology (the great flood myth is recorded in most indigenous cultures), other cataclysms are scientifically and historically referenced (the ice age, dinosaur extinction, seven year’s war between England and France). Wilder is intentionally out of chronological order, suggestive, melding various historical/cultural documents of literature and religion with scientific discovery. Throughout, the vital thread is humanity’s survival.

The questions the characters raise which float throughout each act are philosophical and moral. For example is the human race worth saving from the struggles, trials and horrors which will continue to threaten both people and their environment? Should humanity just throw in the towel, lay down and refuse to repair itself or evolve technologically, artistically, scientifically? Given the rapacity and murderous ruthlessness of son Henry (aka the Biblical Cain, the spirit of murder in humanity), will the human race just exterminate itself with weapons of its own making? Or as humanity’s mother, Ruff’s Mrs. Antrobus suggests, will the family unit sustain the human species, enabling it to succeed in each progressive and evolving era?

Given the latest foray into extinction by Vladimir Putin as he attempts to obliterate Ukraine into the dust bin of history, bully democratic countries to heel to his genocide, and bribe apologist lackeys in the extreme global radical right, including the QAnon members of the Republican Party, Wilder’s overriding questions are current. This is especially so in the last segment when Ruff’s Mrs. Antrobus and daughter Paige Gilbert’s Gladys emerge from the basement where they’ve been sheltering for a seven years war to reunite with Sabina (Gabby Beans). All welcome the new peace. However, they consider how they will rebuild as they view the burned wreckage of their bombed out home.

As the curtain of the last act rises on the devastation, one can’t help think of Ukrainian towns (the Russian soldiers have since left), and Mariupol, where Ukrainian families and soldiers shelter in basements and in a steel factory, as they suffer Putin’s inhumane starvation, while bombs blast above, uselessly pulverizing dust. The irony is so beyond the pale; Putin bombs dust in helpless fury while every minute the heroism, bravery and resilience of Ukraine’s “Antrobus” spirit thrusts into the heavens, memorializing that Ukraine will never capitulate to the likes of Putin. It is a humiliation for Russia. They for allowed such a serial killer to usurp power, genocide women and children and bomb dust because the Ukrainians embody the slogan, “live free or die,”refusing to bow to one man rule and an abdication of their human rights.

Electing to die honorable Roman deaths, rather than submit to Putin’s vengeful, psychotic temper tantrums, they shame those officials who pretend to uphold democracy but, like Putin, vitiate human rights with lies. Uncannily, what’s happening in Mariupol dovetails with Wilder’s prescient theme, that the human race will never capitulate to fires, floods, and its own murderous instincts.

Though Sabina grouses that she’s sick and tired of being sick and tired as she begins the first lines at the top of the play again, the wheel of irrevocable change and life goes around once more with new things for humanity to learn in a new way that is never a repetition of the past. However, Sabina doesn’t see that human history is a spiral and not a circle. She is blind to the human experiment, which Wilder suggests we must understand beyond her limited vision.

Indeed, no human being desires going into survival mode. But cataclysm squeezes out benefit from humanity’s collective soul during great trials. Wilder suggests it is worth the price. Through these actors’ sterling portrayals, we understand that human tenacity and hope propel the human race to make it to the next day. And as the species collectively moves through the days, weeks and years, it evolves a finer wisdom, strength and efficacy. Wilder suggests, this is confirmed again and again and again with each debacle, each disaster, each cataclysm, each deranged maniac that would make war on his brothers and himself.

Some scenes in this enlightened production are particularly adorable. The representative sentient beings of the ice age, the dinosaur and mammoth are the most lovable pets thanks to the brilliant puppeteers (Jeremy Gallardo, Beau Thom, Alphonso Walker Jr., Sarin Monae West).

Unfortunately, Antrobus (the solid James Vincent Meredith), tells the dinosaur and mammoth to leave the warmth of their Jersey home so he has room to take in refugees like prophet Moses, the ancient Greek poet Homer and the three Muses: Melete, “Practice,” Mneme, “Memory” and Aoide, “Song,” who would otherwise freeze to death. The dinosaur’s and mammoth’s expulsion is heartbreaking; the ice age destroys their kind. However, Wilder ties their extinction to necessity. Humanity gave up some unique, particular species and from that arose incalculable value. In this instance the preservation includes the foundation of human laws of civilization, timeless poetry and the spirits who inspire art to soothe the collective human soul and generate its hope and creativity.

The sounds of the ice shelf moving, the projection of the towers of ice and the smashing of the home are particularly compelling thanks to the technical team, as the Antrobus family and their maid and sometime object of Mr. Antrobus’ affections escape, “by the skin of their teeth.”

Wilder’s zany, human account has the same setting of bucolic New Jersey throughout. In Act II it’s still New Jersey, but it’s the wild equivalent of sin city in Atlantic City and the boardwalk that has a carnival atmosphere with a lovely gypsy fortune teller (Priscilla Lopez) who warns Antrobus that she can tell him his future, but his past is lost and incomprehensible. It is an interesting notion because one then thinks of the adjuration, “those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it.” However, this doesn’t quite follow for the Antrobus family who are forward moving in progress.

Lopez’s Fortune Teller predicts the great deluge. Terrifying warning sounds rendered by a huge mechanism register the wind velocity and impending storm ferocity. The sounding of the alarm of the impending deluge is scarily effected. Warnings are ignored by the tourists and those who enjoy the fun, dancing, drugging and alluring lights of the Atlantic City boardwalk. As doom approaches, they party. Of course the Antrobus family flees to a boat after pursuing their natures (slippery Robertson’s Henry has killed someone else). Gabby Beans’ Sabina follows them, a veritable member of the family in her seductions of Antrobus, manifested in Act II, hinted at in Act I.

A powerful scene in Act III occurs after the war is over and the Antrobuses convene at what’s left of their Jersey home. Henry confronts his father, for he is the enemy and Antrobus senior threatens to kill him. Of all the characters, the murderous Henry is the most useless. The daughter is the golden child as was the child they no longer speak of, the beautiful, gifted Abel who Henry resentfully killed. But in Act III, after Henry expresses his feelings of isolation, loneliness and desolation being insulted and demeaned by his father, there is a breakthrough and resolution which is heartening. The scene, beautifully rendered by Julian Robertson, who is in his element as the enraged and hurt son and James Vincent Meredith as the commanding then empathetic father, suggests that hope and love are possible through communication.

Director Lileana-Blain Cruz shepherds her fine, spot-on cast with aplomb to performances that never appear off focus or muted for Wilder’s unique characterizations.

The fun of this production also is in the set design, aptly configured by Adam Rigg, effervescent and vibrant in the first two acts, symbolic and moving in Act III. The colorful costumes by Montana Levi reveal the time periods. Act I presents suburban housewife and family and children with happy-go-lucky flowery dresses, with the appropriate fur coat and stylized costumes for Homer, Moses and the others. Act II presents the 1920s flapper style and for the men the orange pin stripes typically emotive for officials of the Convention for Mammals. The lovely Fortune Teller outfit is glamorous, as she is like a Hollywood celebrity and Sabina is the seductress in shimmering red. In Act III the outfits are back to the housewife/mother and maid look similar to the costumes in Act I. Levi’s stylized flair takes in the themes of the act and threads the overall survival mode of the play with precision and care.

With Blanco, Yi Zhao’s accompanying lighting, Palmer Hefferan’s terrific sound design and the integrated, vital projections by Hannah Wasileski, the artistic technical team provides the canvas which sets off the events and the performances, making them more striking. Even more fun are the expert puppeteers who made me fall in love with the animals and shed a tear at their demise. I am calling out these individuals again, BRAVO to Jeremy Gallardo, Beau Thom, Alphonso Walker Jr., Sarin Monae West.

I’ve said enough. Go see it. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.lct.org/shows/skin-our-teeth/