Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

‘Downstate’ a Powerhouse of a Play, With Sterling Performances

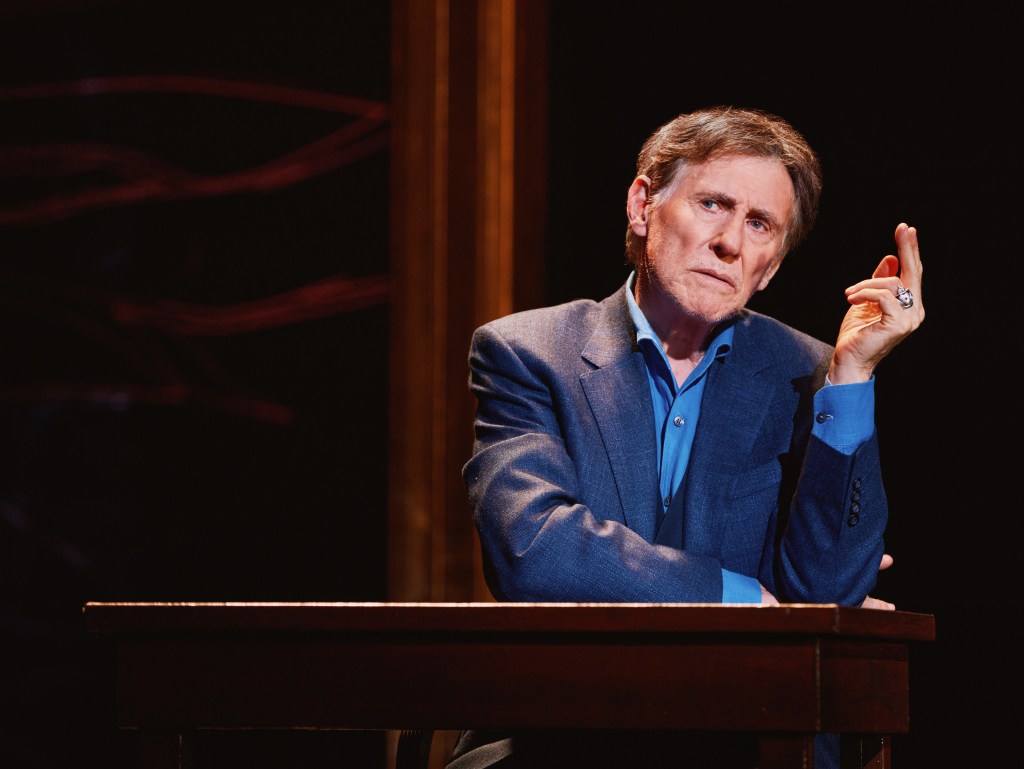

Do we ever receive justice for wrongs done to us if the wrongdoer goes to jail and apologizes? Or are we so damaged no justice or forgiveness is possible? In Downstate, Bruce Norris raises such questions and many more in his compelling play superbly directed by Pam MacKinnon currently at Playwrights Horizons.

At the top of the play the reserved Andy (Tim Hopper) and his concerned wife Em (Sally Murphy) sit opposite Fred (Francis Guinan) who is a senior gentleman, disabled in a motorized wheelchair. As they attempt to discuss why Andy has come to visit, Dee (K. Todd Freeman) comes in with a shopping cart with groceries and Gio (Matthew J. Harris) quibbles with him about the money he owes Dee for bananas. Surveying the house and the roommates, only Fred is white, we surmise this living arrangement has been forced. As it turns out, all four roommates including Felix (Eddie Torres) who eventually comes out of his bedroom to make himself breakfast are convicted sex offenders, who wear leg braces so their activities may be monitored.

Andy visits Fred with Em to discuss Fred’s predation which happened over thirty years ago, when Andy was twelve and Fred was his piano teacher. Andy tells Fred he ruined his life and he can’t function the way he felt he could have if Fred had left him alone. Norris intimates subterranean clues why Andy has taken the liberty to visit Fred. Though Fred didn’t have to, he agrees to see Andy. In his 40s Andy is not supposed to be anywhere near Fred because Fred has served time and has been convicted and is currently transitioning and living in the half-way house. That Andy seeks Fred out and travels from Chicago to Downstate with his wife to deal with Fred is problematic and portentous.

After Andy and Em finish reading letters of judgment and recrimination they’ve written to Fred which Fred listens to calmly, they both reiterate that Fred is evil. When Em senses Andy is hesitating, she tells him to stop backpedaling and continue with why he’s come to see Fred. It is to get a full admission of what Fred has done to Andy. Fred insists he admitted to all of his actions in court, apologized and was sentenced. As they attempt to continue this discussion, the roommates are attempting to live their lives, get ready for work, make breakfast and use the bathroom. Clearly, the couple are a disruption to Dee, Gio and Felix. Yet, Em and Andy take umbrage at the activities around them interfering with the seriousness of their meeting. It is apparent that the mission they are on obviates the humanity of the other men whom they look down on. In their self-righteous ferocity there is an underlying remoteness and cruelty that Norris reveals in superb dialogue acted exceptionally.

Indeed, Andy and Em are so absorbed in Andy’s victimization and his wish to fully confront Fred with it, they become annoyed by the interruptions in an environment which Andy admits does not fit his expectations. It is as if in Andy’s imagination, he expects Fred to be a silent robot upon which he can unleash vilification without Fred responding as he sits in an isolated room just to listen to Andy’s rant about him. And ironically, part of that logical diatribe includes Andy telling Fred he has fantasized killing him. Interestingly, Fred responds with humanity and humility. He is apologetic and kindly to Andy which Andy ignores and dismisses. Andy reiterates that he has a right and is not supposed to feel empathy for and forgive Fred. Fred can extend him grace, but he doesn’t have to or want to receive it nor will he bestow it.

Norris does an impeccable job of revealing the humanity of both sides of the equation, especially in indicating that Andy, who is in therapy, has no idea how Fred’s life has been altered by what Fred refers to as his own sickness and deserved punishment. He believes Fred to be a fake. Tim Hopper’s Andy, Francis Guinan’s Fred and Sally Murphy’s Em are sensational in their performances listening acutely to each other and reacting with spot-on authenticity. Indeed, though we feel for Hopper’s Andy, Guinan’s Fred who is unassuming, childlike and kindly pulls us in and encourages our sympathy. When he reveals in a later discussion with Andy in Act II that an outraged fellow prisoner slyly brought in steel toed boots and kicked Fred so that his back was broken and he has to have a colostomy bag and can’t walk, we consider Andy’s “breast-beating” and Fred’s indulging him to be beyond ironic.

The relationship between Em and Andy as Norris infers, and the actors ingeniously perform with nuance, reveals there are intimacy issues and problems. Thus, Andy’s psychology seeking out Fred is much more complicated than having him sign a reconciliation paper. In Act II the complication is further exposed and we note Andy’s emotional issues which he can’t confront in himself. These allow him to cling to victimization perhaps for another reason. Clearly, Andy and Em are not satisfied with the “justice” Fred has received and by the end of the play we understand that there is more to predation that happens between victims and their predators, than what there is assumed to be. Perhaps, it is not all on the evil and perverted side of the predator. This is tricky ground and Norris navigates it with understanding, forthrightness and intelligence.

After Andy and Em leave in annoyance, PO Ivy (Susanna Guzman in a fine performance) visits. It is here where we begin to understand how the individuals are monitored and hated by the outside community. Also, the problems that they face living in the house are not being addressed by the state, another example that they are a bottom priority. For example, the house needs a broken window and a leaky septic tank repaired. Ivy tells them that they should pay for the repairs themselves. She is too overworked to deal with it. There are more important reasons for her visit. Ivy brings information which indicates the culture’s judgment of sex offenders has mandated increased restrictions on their transportation and mobility. When Dee asks for the particulars, they discover that the routes they must now take are illogical. The point is that the neighborhood opposes their being in the area and petitions constantly for them to leave; the mandate is a sop thrown to the neighborhood.

Norris also outlines the interactions between the four men. Gio and Felix, who are religious, act superior and reject Dee’s lifestyle as a homosexual. Gio accuses Dee of taking advantage of Fred, who needs help bathing and toileting and pays Dee. Meanwhile, Ivy confronts Gio about his behaviors and he is defensive, insulting and bullying. She has to warn him that she can send him back to prison if he doesn’t shape up. In Ivy’s interactions with Eddie Torres’ Felix, we note her attempt to be even-handed. However, in Guzman’s questioning of Torres’ Felix, again, we feel for both characters. She must do her job and Felix is trying to live his life and at least reach out to his daughter on her birthday. Torres is spot-on in his emotionalism and his broken-hardheartedness. His portrayal is beautifully human and tugs at our hearts.

As a secondary character of great importance, Gio’s co-worker, Effie, has a friend who is a sex offender, so she should know the balancing act that must be taken with offenders. She doesn’t care. Norris uses her character as a catalyst. She has become close to Gio and plays fast and loose with his status as a first time offender found guilty of statutory rape with a minor. Gabi Samels’ Effie is provocative, high wired, a “wise-ass” and loud-mouth, knowledgeable enough about the law to use it with Guzman’s Ivy. Through Ivy and Dee’s response to her, we note her ADHD carelessness and irresponsibility is a train wreck waiting to happen.

K. Todd Freeman’s Dee serves as the house master, who on the one hand is aware of everyone’s business, but also watches out for each of the roommates, regarding their rights and responsibilities not to screw it up for each other. Sometimes it is efficacious and other times it backfires. Norris has given Dee the most humorous, witty, intelligent and lovable lines as a former show business person and lover of the arts. Freeman is incredible as the black, senior homosexual, who makes the perfect ironic retort when coming up against bigotry, hypocrisy and cruelty, displayed especially by Gio and Andy. Freeman and Guinan show their prodigious acting talents in establishing the caring, kind relationship between Dee and Fred. In their interactions with Gio and Felix, their performance is nuanced, and Freeman’s ironic delivery as Dee, who uses his humor to lay bare Gio’s arrogance and Andy’s internal psychological fears, is breathtaking.

Norris’s characterizations are beautifully drawn. The playwright enables us to better understand the impact of the hatred and fear leveled by a culture that has little mercy for individuals such as the offenders in Downstate. The humanity that the actors portray in Gio, Fred, Dee and Felix is heartfelt, poignant and tragic. As those on the outside, Andy, Em, Guzman and Gabi Samels are edgy and powerful. All of the characters’ interactions are organic, complex and nuanced. Not enough praise can be given to Pam MacKinnon for shepherding the fine performances of this stark, amazing, forceful ensemble piece.

Norris has set up the action threads in Act I, that he unravels to explode sensationally in Act II. There is no spoiler alert in this review. You will just have to see Downstate to find out the conflict developments between Andy and Fred, Ivy and Felix, and Gio and the catalysts Dee and Effie. The result is cataclysmic and heartbreaking

Kudos to Todd Rosenthal’s scenic design, Clint Ramos’ costume design, Adam Silverman’s lighting design, Carolyn Downing’s sound design, which are perfect for the reality and drama that MacKinnon’s vision requires. This gobsmacking production is one to see for its themes of love, humanity and grace, its wonderful performances and ensemble acting, and its overall production design. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.playwrightshorizons.org/shows/plays/downstate2223/

‘Ain’t No Mo,’ the Uproarious Satire Explodes With Brilliance on Broadway

Ain’t No Mo which premiered at The Public Theater in 2019 brings its scathing, sardonic wit and wisdom to Broadway in a broader, handsomer, electrically paced production with incredible performances and extraordinary, complex dynamism. Presented by a host of producing partners with Lee Daniels topping the list and The Public Theater end-stopping it, Jordan E. Cooper’s brilliance now can be appreciated by a wider audience. Directed by Stevie Walker-Webb, the production shines brightly with the creative team of Scott Pask (scenic design) Emilio Sosa (costume design) Adam Honore, who also was responsible for lighting design in the Public Theater production, Jonathan Deans and Taylor Williams (sound design) and Mia M. Neal (hair & wig design).

The tenor, structure and characterizations which send up Black cultural attitudes and systemic white institutional racism and fascism in Cooper’s excoriating farce and brash, in-your face cataclysm of vignettes, remain essentially the same as the Public’s production which I adored and thought incredibly trenchant (https://wordpress.com/posts/caroleditosti.com?s=ain%27t+no+mo). Based on the premise of the political collapse of the country with Putin installing Donald Trump as president (my opinion as per the Mueller Report) as the main conceit of the play, the government offers a one-way flight back to Africa for all Blacks.

This was a perfect trope in 2019 and still is. Though we have a different administration in the presidency, the same pernicious elements that uplift oppression and inequity refuse to submit to the constitution which safeguards Black citizens and all citizens’ rights. Indeed, since 2019 the villians are hell bent to vitiate as many of our rights as they can. So Cooper’s play is tremendously vital as a clarion call against white supremacist tyranny and despotism at the heart of Trumpism and Republicans’ silent agreement with it.

Cooper attempts a few updates in this production since 2019. He references Black Lives Matter and Vice President Kamala Harris. However, he omits references to the horrific changes in the political climate which has worsened. Nor does he reference the Biden presidency which has sought to reverse every perverse corruption the Trump presidency and Republican party in silent complicity wrought on the country. Trump’s blasphemy of democracy, the January 6th insurrection and COVID botch job (read Bob Woodward’s book Rage) where Trump wittingly exacerbated the proliferation of the virus, killing the most vulnerable communities (persons of color, the elderly) are not mentioned in this production. The updates are unnecessary because Cooper’s themes are more current than ever. In fact they are prescient and hilariously frightening.

The Trump Republicans have continued their fascism and racism with a new vengeance against the Democratic Party which appears to stand for democracy and accountability. At this writing the entire Republican Party has not raised the hue and cry necessary to condemn Trump’s association with two individuals who support white supremacy, Nazis and in particular one individual’s praise of Hitler as a Holocaust denier.

Such white supremacist oppression and outright tyranny are the key points of Ain’t No Mo which suggests truth in ridicule and doesn’t posit simplistic solutions. Cooper’s genius with Stevie Walker-Webb’s superb director’s illumination REPRESENT metaphorically. Within the high-anxiety, farcical elements of the play are the roiling currents of fear and anxiety that reveal what it is to be black in the United States today, regardless of whichever black socioeconomic class one fits into.

This is especially so after the January 6th insurrection, 1,100,000 pandemic deaths and the screaming lies of white supremacist terrorist QAnon politicos like Louis Gomer, Marjorie Taylor Green and fist pumping Josh Hawley. It is especially so as Trump acolytes whitewash violent behaviors as patriotic expressions of freedom, in a cover-up of what they actually are, crimes against humanity and an attempt to destroy the constitution and the rule of law which holds white supremacist terrorist criminals like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys and their encouragers (Trump’s allies) accountable.

Thus, Cooper’s prologue set in a local black church in 2008 at a metaphoric funeral service of Brother Righttocomplain is beyond perfect. Pastor Freeman, the wonderful Marchant Davis, proclaims that the election of black president Barack Obama will save the black community and remove their need to protest injustice, inequity, police brutality and lynchings, and racial hatreds. Parishioners (Fedna Jacquet, Shannon Matesky, Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Crystal Lucas-Perry) dressed in tight white dresses, thanks to Emilio Sosa’s outrageously funny costume design, scream and shout the glory. These congregants affirm with Pastor Freeman that the “light-skinned” (an irony) Black president will solve all their problems as their very own messiah whose freeing power they “own.”

Cooper’s memes and jokes are acutely ironic and a veritable laugh riot. For example he affirms that Obama is their “ni&&er” and as such there “ain’t no mo discrimination, ain’t no mo holleration, ain’t gone be NO more haterration…” The good reverend lists an end to every conceivable example of racist terror visited upon Blacks since the Civil War because with a Black president, abuse of the Black race by an unjust government will now stop. Of course, this is an irony because learned behavior and systemic institutional racism is so complex and entrenched, everyone in the nation must work very hard to overcome it. Given the pockets of prejudice and discrimination even in blue states, this is easier said than done. Cooper illustrates this beautifully by the conclusion of the opening scene.

With the burial of Brother Righttocomplain, “Freeman” preaches “ain’t no mo strife, no more marches to be led, no more tears to be shed…” in celebration of a real “going home party.” Of course, when Pastor Freeman hears gunfire as the parishioners praise, sing and dance, reality makes its ugly appearance. With sirens, cop cars’ flashing lights and gun shots, the future descends during the Obama presidency and afterward to the annihilating Trump presidency.

Above the shouts of praise Marchand’s Freeman hears the overwhelming news reports of the Flint water crisis, deaths of Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, Aiyana Jones, Rekia Boyd, Jordan Davis, Alton Sterling, The Charleston Nine and countless others. The reports reveal Freeman’s overestimation of Obama’s power as a Black president to mitigate racial hatreds and alleviate the social oppression Blacks experience every day. The same discrimination and violence raises its ugly head, despite President Obama’s best efforts to stop it. So the foreboding harbinger of the Trump presidency’s return to Jim Crow 2.0 terrors hover, unless blacks hop on those flights to Africa on African American Airlines. If they evacuate, they will save their lives. If they stay, they lose everything including their black identity and will end up dead or in prison.

Of course Cooper’s Africa evacuation is what President Abraham Lincoln suggested as a way to solve the “negro question” after the Civil War was over. However, Frederick Douglass stood up to Lincoln and vociferously opposed leaving because the United States was their country since 1619, and their association would never be African because their tribal history had been taken from them.

As a solution to the hell of Black America’s unequal treatment under the law, evacuation to Africa is Cooper’s over-the-top response. It is a double irony considering that once again, Blacks are introduced to a new form of dispossession, alienation, abandonment and diaspora, while the oppressive white culture “owns” all of the historical contributions Blacks have made in the arts, sciences, government, technology, industry and every field imaginable. In the play African Americans’ contributions reside metaphorically in a lovely bag which flight attendant Peaches (the inimitable Jordan E. Cooper) tries to take with her as she attempts to board the flight. But symbolically, the bag cannot be removed to Africa. And trying to leave with it, Peaches misses the flight and loses her identity and everything she’s fought for as an American. She is reduced to the state of those who survived the Middle Passage and were set up to be auctioned off as slaves. But she is “keeper” of the bag and recognizes that she is left to represent Black culture and identity.

Another key point Cooper makes with the symbolism of the “bag” is that the greatest Black contributions have been forged in the crucible of slavery and subsequent decades of oppression as Blacks and the culture have changed laws to be more equitable. Black contributions are as indelible to who Americans are as a culture and society as the Native Indian lands are the foundation upon which this nation has been built and has prospered. Though white oppression and white supremacist tyranny vaults its own greatness in lies, ignoring such contributions, it is a dangerous oversight and underestimation of Black energy, vitality and creativity. American greatness is in its diversity, and the culture and society will thrive if no one is left behind or evacuated. We must work together and seek equity for all to be great (an underlying theme of Cooper’s play).

After the opening prologue the play’s structure alternates between vignettes of various Black Americans’ response to escape to Africa and Peaches’ growing frustration boarding passengers under a deadline as an exit strategy from the hell of the coming white oppression. Cooper’s Peaches is wonderful as the wired, loud, candid, funny flight attendant who prods her passengers with the consequences of staying: prison and confiscation of everything they own or death (transmogrification). With each vignette we are apprised of the oppression Blacks have been conditioned to which is the foremost reason why Blacks should leave.

In the “Circle of Life” sequence which takes place at a clinic (since Roe vs. Wade was overturned with Dobbs, this is a particularly poignant scene) we watch the digital counter enumerate that are millions in line to terminate their pregnancies rather than give birth to a child whose days are numbered. Surely odds are they will end up as a statistic of police brutality, gang violence or other casualty of an oppressive culture which has come to kill those who drive or walk “while black.” Damien (Marchant Davis) tries to convince the pregnant Trisha (Fedna Jacquet) to keep his child rather than abort it. However, he is a spirit, shot to death, so Trisha who waits with another woman for almost two months finally goes into the room for the procedure as the plane arrives to begin boarding passengers in a humorous end of the scene as one pregnant woman thinks the plane is filled with the “9/11 bit*&es,” coming for their heads.

In a revelation of how Black identity is twisted and nullified by the culture, “The Real Baby Momas of the Southside” is a hysterical parody of any of the puerile reality series which reduce women to silly, gossipy, back-biting, angry, fools, whether black or white, as “benign” entertainment value. God forbid if this were a political show which demonstrated their intelligence and erudition. Instead, memes of what Black identity means come to the fore in this humorous and drop-dead serious send-up of shows which exploit the idea of “being Black.” Some of the funniest lines come when the women are off camera (the cameramen are white) and we discover that they don’t have children and speak without accents and epithets. We see the show is a blind to please and brainwash the audience, who enjoys seeing how “low-class” Black women are. Meanwhile, there are other ways of being, but this isn’t a show about how strong, forthright, powerful and intelligent Black women are.

“The lighter the skin, the better” is a reality Blacks have had to deal with because of white fascist physical mores. The trend has morphed over the decades into a perverse reverse. Other ethnic groups including whites have embraced the “Black ethos” in a perverse acceptance of only the superficiality of “being black” without accepting or recognizing any of the horrific sacrifices Blacks have made over their 400-year history in this nation. Cooper’s beautiful example of this appears on steroids with the character Rachonda, whose real name is Rachel (Shannon Matesky). She is a baby mama the others reject because she is white and is going through transracial treatments to become Black. When she is called out on it in a LOL moment by Tracy (Ebony Marshall-Oliver), Kendra (Fedna Jacquet) and Karen (Crystal Lucas-Perry), she reveals that she has no clue about Black American sacrifices and and just wants to ride the current wave of Black female “cool,” generated by Michelle Obama. She never receives the email inviting her to escape to Africa, caught between her memes and unconverted to her “full Blackness,” an irony.

In the last two vignettes before Cooper’s exceptional, heartfelt conclusion, the first reveals a wealthy Black family who embrace white upper class mores, genociding their own identity to convince themselves they belong to the superior, fascist, master race (like a celebrity who recently praised Hitler). By internalizing white supremacist values, they don’t even realize they have destroyed their identity, their souls and their uniqueness. Furthermore, by adopting the”white” ethos as the proud bourgeois class, they have trampled all those who have shed blood to advance the hope of achieving civil rights, equal opportunity and justice by overcoming institutional racism. The bourgeois family don’t believe they are oppressed because they live by the “green.” The supremacists would never come for them because they have money.

We don’t realize how brainwashed they are until Black (the amazing Crystal Lucas-Perry) emerges from her prison underneath the mansion where their wealthy father has chained her for forty years. Finally free, Black confronts them in one of the most wild, convulsively humorous and hyperbolic rants about their blackness and the imperative to leave for Africa. They are so “white-fascist-think,” the truth she speaks is anathema. They kill her (typical Black on Black crime). The neighbors hearing “Black” screaming non bourgeois are infuriated about it. They call the police right at the precise moment Black has been genocided.

The scene is a powder keg of dynamite performances which are memorable and tragic because the family believes that they are a different identity via the “green” (money). It doesn’t matter if they stay or go. They have already lost everything valuable about what their culture means. Staying, they lose their lives. Cooper’s theme is clear. An oppressive fascist culture has as its most horrific tactic, get blacks to destroy the finest traits about them, their Blackness, by rejecting it and internalizing white tropes. Without that Blackness, they embody the worst of the fascist “master race.” They genocide their own and themselves.

Cooper also identifies the Black, female prison population in a very powerful scene. When freedom is posited, one of the prisoners, Blue (Crystal Lucas Perry transitions to a completely different mien and aura) hesitates to leave. In great fear and rage from all the abuse of her past, she creates a situation where she almost destroys her chances for freedom and is killed (or never makes the plane and is transmogrified). How Cooper ends this vignette and the last one when Peaches doesn’t make the flight to join those evacuating the US, are memorable scenes. They leave the audience in awe. The majesty of the actors’ performances and the stark language laden with substance and richness are stunning.

It is a supreme irony that though there is not one Caucasian in his play, Cooper’s themes and messages are particularly for those who have been blinded to believe that their skin color exempts them from white supremacy’s tyranny. It is only a matter of degree. Despotism impacts everyone in the culture as Cooper indicates in the last scene of the play.

In the end scene, the jet pulls away as the Blacks leave for Africa renouncing everything to go to a safe haven, while Peaches is left “holding the bag,” though it cannot be pulled up from the very place on which it rests, having become rooted to America. Cooper’s hyperbole may seem a farcical extreme. However, what they escape in the play we all faced because of the tyranny of the former president, who weaponized of a pandemic which killed a larger proportionate number of blacks and people of color. The blasphemous white supremacist tyranny the Blacks escape via his play’s metaphor, in reality, incited an undeclared war against U.S. democracy in a violent insurrection to thwart the peaceful transfer of power when Trump lost the election. Cooper’s understanding of the murderous intent of white supremacy is divinely inspired. He is a veritable Cassandra in his ability to read the ominous signs and incorporate them in this play. So the point that the only safe haven from such white tyranny is a return to Africa has been made palpable in the Ain’t No Mo, 2022.

The work is breathtaking in its themes, performances, writing and artistry. Don’t miss it. For tickets and times go to their website https://aintnomobway.com/ You will belly laugh and be moved at the same time.

T

‘You Will Get Sick’ Linda Lavin is a Breath of Fresh Air

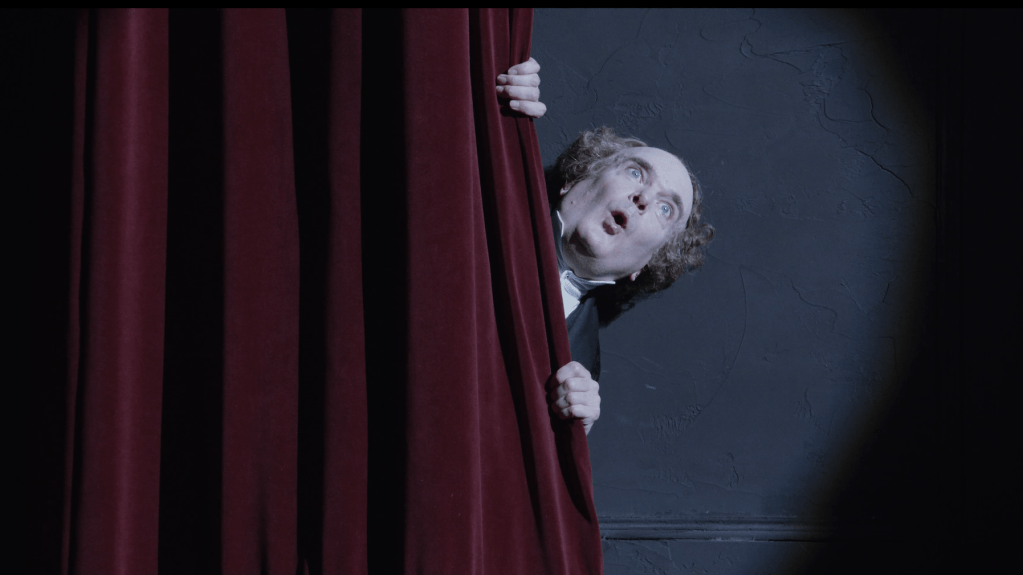

Sometimes the best way to accept the inevitable is to step into the realm of the fantastic and approach the unapproachable through magical thinking and an encouragement toward vacating reality. In You Will Get Sick by Noah Diaz, directed by Sam Pinkleton presented by the Roundabout Theatre Company, the unnamed characters traverse through unspecified settings and manage their lives of quiet desperation with humor and a sense of camaraderie that comes with a price. The price is avoiding the blinding truth until they are ready to receive it.

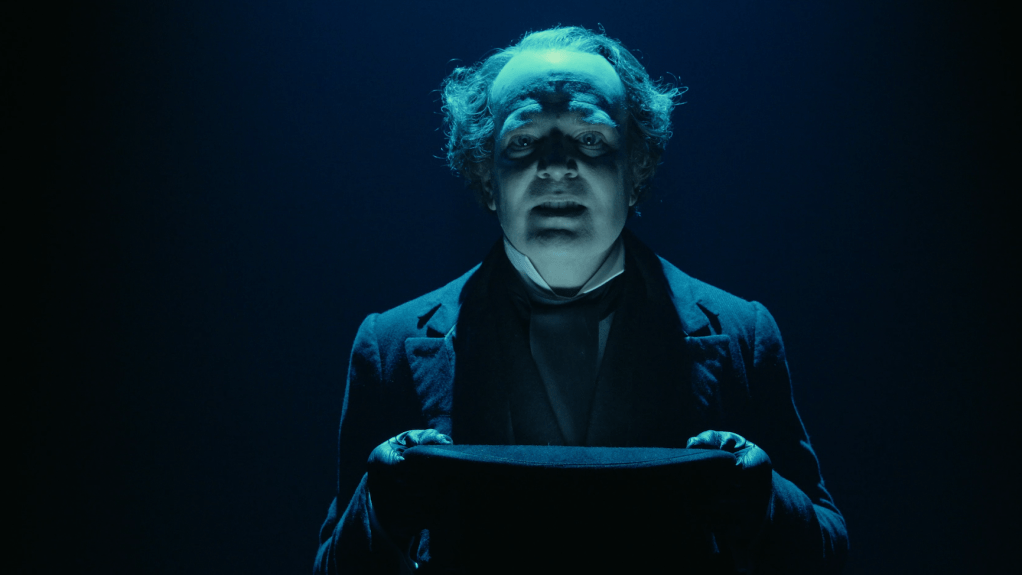

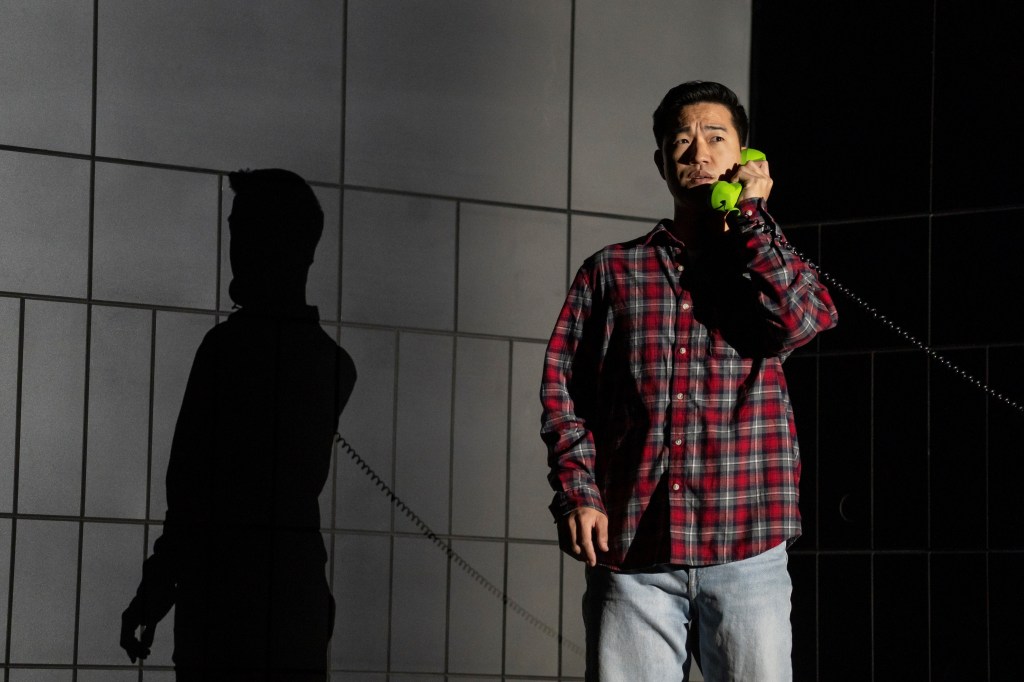

Daniel K. Isaac’s character is the emotionally distant, sweet #1, who has a phone conversation with Linda Lavin’s #2 at the top of the play. Initially, I questioned why they speak to each other since money is discussed upfront and it wasn’t clear what the exchange services were. However, when character #2 straightens out how she wants the money delivered, we discover she is an actor, is on a project and above all needs to supplement her finances. Character #1 eventually clarifies the services he pays her for in this absurdist, quirky play whose surreal elements are funny, surprising and metaphoric.

Interestingly, there is an internal war in character #1, which we may identify with at one level or another. He has been in denial about the severity of his illness. The initial service he requires of #2 is to listen to him as he tells her about his condition, so in the telling he can acknowledge what he is going through, confront it and then position himself to tell his sister. At least he knows he is in denial. Blindness related to not admitting the signs of disease when they first appear is a typical reaction, unless one is a hypochondriac, which #1 clearly is not. When we understand what #1 is going through, we consider COVID-19 deniers.The most extreme were on their death beds scorning their nurses and doctors’ COVID diagnosis. These went to their deaths with the peaceful conviction that anything other than COVID was killing them.

Though #1 isn’t as blind as those individuals, he can’t reconcile his illness. He can’t even admit to himself that his body is falling apart, that his hands are growing numb, that it is becoming harder to walk and impossible not to fall in the shower. His condition is incurable and there has been a diagnosis which we never learn. Yet, as the play progresses, #1 struggles with himself emotionally and must be as detached as possible to begin to comprehend that the plans for his life, his hopes and dreams have been shuttered by the drama that is overtaking his body’s ability to function.

Many youth who are immortal until they aren’t, think that illness is what happens to the old and feeble. However, this doesn’t appear to be Character #1’s thinking…that sickness is for the old. We discover later in the play in a discussion he has with his sister that he is aware that sickness can impact the young and kill them. In fact he took care of his sibling Patrick who was ill, maybe of the same disease, and nursed him until he died. So he is not a callow thirty-something. Clearly, taking care of his brother was a sacrifice of love, but it took its toll on him. In his discussion with his sister, #1 states he doesn’t want her to take care of him, nor does he want aides to help out. Somehow, he will deal with this on his own and allow the illness to take its course. The recognition of the impact of illness on family, since he has had that experience, most probably has overwhelmed him. Denialism and blindness allow one to transition to the truth gradually.

The first step in #1’s plan is to come back from denialism and face reality with someone who is not a relative. To do this and remain less emotionally overwhelmed, he decides to pay someone to listen to him reconcile the fact that he is “sick,” though he never frames it as an illness that is cutting short his life. That is a bridge too far, and one he is not ready to cross. Thus, Lavin’s humorous character #2 becomes the one to take on the impossible burden of listening to him as he describes factually what his body is doing. Character #1’s mind and emotions are so shut down, he can’t discuss this with his co-workers or his sister, just yet. Character #2 will help prepare him for those discussions.

Character #2 is desperate for the money and does odd jobs and takes acting classes so she can become good enough to audition for the role of Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. Character #2 and #1 are idiosyncratic and pursue their own realities and somehow manage to accept one another’s weirdness with generosity so that what they both wish, they help each other achieve. The actors are superb in making the unusual seem regular with their direct, in the moment authenticity. Importantly, though they are not friends, #1 and #2 help each other feel less alone against the personal trials they face.

Character #1’s connection with character #2 strengthens after he sends her a check which he didn’t sign. That forces a face-to-face meeting which leads to other meetings, the next when he hires character #2 to tell his sister (Character #3 is Marinda Anderson) about his condition. When the three of them meet, Diaz constructs a humorous scene in a restaurant with a crying waiter (Nate Miller) that Pinkleton directs with excellent pacing for humor. After this meeting with his sister we understand the limitations of family and why #1 doesn’t want to bother her about what he is going through.

In addition to his illness, #1 faces another problem. He must escape the monstrous birds that sound like crows, who prey upon and kill the sick. Nate Miller’s character #4 plays a number of parts relating to the bird menace. One is a salesman who sells insurance to protect against the humongous birds. Another is a despondent waiter (he appears in #1’s meeting with his sister) whose mother was taken by a monstrous bird. Thus, on top of having to confront the deterioration of his body, #1 has to beware of these other worldly birds. Interestingly, #2’s attitude toward the bird attacks is sanguine, almost uninterested. She will stay well as an older person and help this thirty-something in his illness. Theirs is an ironic reversal of the natural order of things.

Character #2’s response to Miller’s bird insurance salesman sums up her reaction to most things at this point in her life’s experience. She tells him a choice epithet about where to go. Linda Lavin’s #2 uses epithets as seasonings to make her delectable, unstoppable character more immediate and no nonsense. Lavin, with decades of know-how has fine tuned her rhythm and timing for humor, cleverly waiting for the chortling laughter that always follows her character’s well-placed retorts.

Diaz messages a number of themes with these unusual characters who are fanciful but manage to be endearing because they are so vulnerable. Caregiving, Diaz suggests, sometimes requires allurements like money because family can’t always be counted on to help. Sometimes strangers are better attuned because they are not emotional and there are no problematic bonds. Characters #2 and #1 arrive at a congeniality of quid pro quos. #1 even goes to one of #2’s acting classes where they act out “lion” and “tiger” in a humorous segment which actually takes #1’s mind off his condition and physically helps him. Lavin is not only spry at 85-years old, her “lion” and “tiger” steal the show. Her spot-on performance has her addressing the audience and singing an audition song (for the part of Dorothy) in which she ends up in the wrong register. And after trying it a few times, #2 never gets it right.

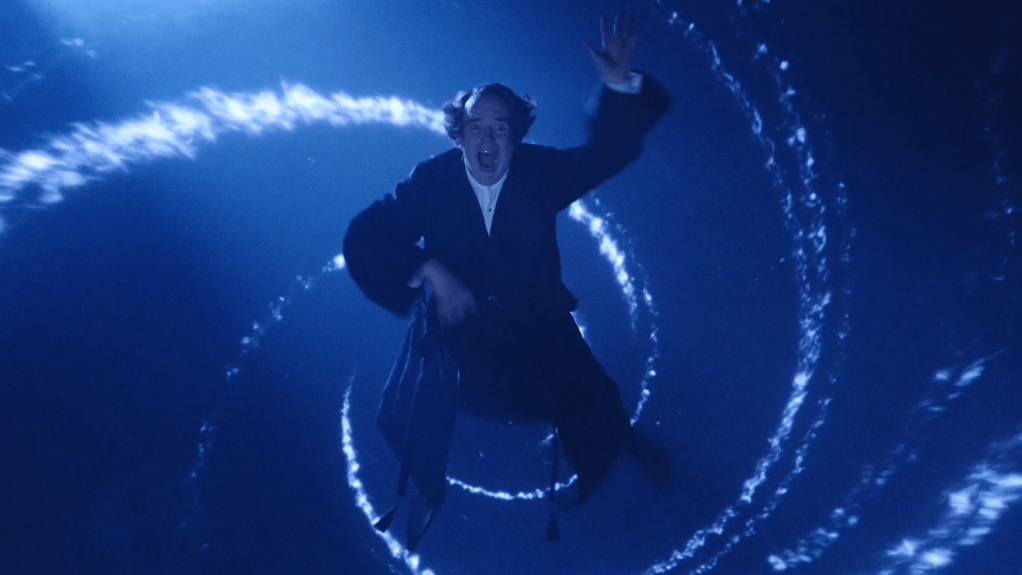

For his part Isaac’s #1 handles the absurdist elements with authenticity. When he spits up the hay, symbolic of where he originated from, and representative of his illness, the action is weird and frightening, but believable. He negotiates the straw-man, scarecrow imagery in the later scenes with matter-of-fact acceptance. These segments and his apparent suspension (with special effects) suggesting tropes from The Wizard of Oz, an iconic story whose verities relate to the characterizations in You Will Get Sick, are fascinating to ponder. However, the playwright is a master of the opaque and uncertain, never really pinning down any particular truths apart from the fact expressed in the title and our susceptibility to our mortal state. That he delivers these themes gently with fantastic elements is enough.

Isaac’s character #1 echoes Dorothy’s wish to return home as related to The Wizard of Oz. Lavin’s #2 helps him achieve that wish as #1 helps #2 achieve her goal. At the play’s conclusion we note that the money #2 has received from #1 has allowed her to purchase a gingham dress and red shiny slippers so she can properly audition for the part of Dorothy, a dream she’s had her entire life.

#1 makes it home. For him home is in a field of hay (though wheat might be more metaphorical). There he meets up with his brother Patrick, Character #5 (Dario Ladani Sanchez) who joins him holding a microphone. It is Patrick’s voice we have heard (in voice over) expressing #1’s interior thoughts throughout the play.

At the conclusion we understand the importance of #5 in helping give #1 solace and comfort to keep his emotional turmoil at bay so he can function and find his way to “get back to where he once belonged.” At home in the field with Patrick, #1 is able to breathe freely, away from the noise and the hectic gyrations of city life. There, he seems well and is in his right place. The metaphors settle into a finality at the conclusion. Indeed, the human condition vies between sickness and wellness. As Diaz’s title suggests, humans are mere mortals. There is an immutable inevitably of sickness. During it, if we are fortunate, we will “get back to where we once belonged” (our home and what that means to us).

Kudos to dots (set design) Michael Kross and Alicia Austin (costume design) Cha See (lighting design) Lee Kinney (original music and sound design) Daniel Kluger (original music and sound effects) Skylar Fox (magic and illusions) Tommy Kurzman (hair and wig design) who bring Diaz’s play and Pinkleton’s vision of it to fruition.

Diaz’s daring, imagistic play is in its World Premiere at the Laura Pels Theatre, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre until 11 December. For tickets and times go to their website https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2022-2023-season/you-will-get-sick/performances

‘A Man of No Importance’ at CSC, a Superb Revival

In its second Off Broadway go-round (Lincoln Center in 2002) Terrence McNally’s book and Stephen Flaherty’s music with Lynn Ahrens’ lyrics of A Man of No Importance directed and designed by John Doyle, is currently at CSC until 18 of December. The production is Doyle’s unaffecting and warm goodbye as Artistic Director of CSC. The uplifting, poignant musical appropriately reminds us of the vitality of theater, whether it be in an office space or a majestic 1500 seat house on 42nd street. Unlike the titular film A Man of No Importance is based on (1994, starring Albert Finney, written by Barry Devlin, produced by Little Bird) live theater is interactive. The audience spurs on the actors in a kinetic, telepathic bond that is incredibly enjoyable once opening night jitters are put to rest.

This most probably is what keeps protagonist Alfie, a DIY theater director of Dublin’s St. Imelda’s Church players inspired and engaged, though their performances are reportedly terrible. And it is why he is wickedly devastated when Father Kenny (Nathaniel Stampley) closes down their production of Salome, because it is inappropriate and untoward for a community church theater show, though the story is right out of scripture. Actually, by the end of the production we learn that the butcher, Mr. Carney (Thom Sesma), who is one of their amateur troupe, complained to Father Kenny that Salome was tantamount to pornography because he had a small role and that pissed him off.

Alfie (portrayed by the likable and heartfelt Jim Parsons) apart from his love and spirit guidance by Oscar Wilde, who encourages him to read poems while at his job as a conductor on a Dublin bus, is a closeted, sensitive gay man. He lives with his domineering sister Lily (the always superb Mare Winningham) in their small apartment, where he keeps a raft of books and tests out his gourmet international recipes on her unadorned, “Irish stew palette.”

The year is 1964 before the cultural revolution, “free love,” mini skirts, The Beatles phenomenon and a relaxation of Catholicism’s strictures that didn’t really happen until decades later. Then, the Republic of Ireland was repressed and oppressed by doctrine that made it look more like the radical, right-wing conservative anti-LGBTQ, anti-abortion, red state swamp areas of the American South in 2022. Because of such cultural dispossession, Alfie lives in a fantasy world of art, theater and poetry. He remains inspired by his spiritual advisor, fellow Irishman Oscar Wilde, as he tries to improve the lives of those around him, whether at his job as a conductor, at home with his sister, or at the church, directing his St. Imelda Players.

When Father Kenny closes down their amateur troupe, Alfie is quite bereft, until the St. Imelda Players decide to perform a play of the events that have brought them to where they are at the finish line in the present (1964) with no winning trophy. But instead of directing them, Alfie will be the star of their play.

Cleverly, McNally, Flaherty and Ahrens adjusted and adapted the film as a flashback sandwiched by the present. The church players become the Greek chorus who engineer the events of the play, streamlining them into the action that happened at St. Imelda’s before Father Kenny shuttered their company. They sing songs that embody the emotional feeling and turning points of those events. These songs include the conflict between and among the characters, personal confessions and revelations, and the positive message that they gain from what they’ve learned together. They introduce Alfie as their star, then perform the tuneful, ironic opening number, “A Man of No Importance,” in celebration of their beloved friend and director who is their hero, integral to all of their lives. We learn by the conclusion of their musical, that to them, he is a man of great significance.

Doyle has staged the musical with an approach to DIY theater, reflective of what the St. Imelda Players might effect. The props are cleverly selected, i.e. a drum is used as the bus steering wheel. The actors use minimal furniture to create the environs where the events occur. Chairs suggest the bus that conductor Alfie is on with the driver, the affable and lively Robbie Fay (A.J. Shively, whose “The Streets of Dublin” rocks it). The players become the bus passengers with a new passenger Adele, the lovely voiced Shereen Ahmed catching the attention of Alfie as he quotes from a poem by his spirit mentor Oscar Wilde. By the end of their ride, The St. Imelda Players complete singing the titular “A Man of No Importance.”

As the players give us a tour of Alfie’s life in Dublin, we drop in on him with sister Lily, who is happy to discover that Alfie has found interest in a woman. She sings”Burden of Life” as an answer to her prayers so that perhaps now Alfie can settle down, and she can be free of taking care of him. Mare Winningham is humorous and vibrant as she takes on the role of Lily. A Catholic woman, she and the others in the troupe miss all the cues that her brother just might not be into women. When this finally comes out later, she reassures him in the song “Tell Me Why” that even though he is gay, she loves him anyway and he should have told her.

Alfie’s interest in Adele is not because her beauty entices him romantically. He thinks she is perfect for the role of Salome. Though she avers and refuses the part initially, Alfie is persuasive and she finally relents. It is his hope to have the handsome Robbie play the part of John the Baptist, perfectly cast to act with Adele. Robbie puts him off and instead invites him to come to the pub (the wonderful “The Streets of Dublin”). Alfie accompanies Robbie and makes a fool of himself singing “Love’s Never Lost” in front of Robbie’s friends. Embarrassed, Alfie leaves, further disturbed at Breton Beret’s (Da’Von T. Moody) interest in him. Additionally, he’s confounded by the “love that dare not speak its name,” a love that he feels for his “Bosie,” as he imagines Robbie to be. (Bosie refers to Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s lover.)

Alfie can only admit this inner conflict as he looks at himself in a mirror encouraged by Oscar Wilde (Thom Sesma). He sings the lyrical “Man in the Mirror” as a way to work through his emotions to achieve self-acceptance. Parsons approaches Alfie’s inner conflict with yearning and honesty, confessing in a dream-state to the persecuted and vilified Oscar Wilde, a man who understands the torment he goes through.

Spurred by her discussion with Mr. Carney about Alfie’s weirdness (“Books”), Carney’s insistence that Salome is pornography, and his pressure to marry, which Lily puts off using Alfie as an excuse, Lily makes an attempt as a matchmaker. She invites Adele home for a meal that Alfie has cooked. Afterward, Alfie walks Adele home and as a friend, he gets her to admit she has “someone.” Her tears suggest that there is a reason her boyfriend is not with her. To reassure her Alfie calms her with another beautiful ballad, “Love Who You Love.” As she leaves, Alfie bumps into Breton Beret who propositions him. Alfie wisely restrains himself. His intuition is correct but his unresolved conflict between his shame at being gay and his longing to find someone to be with is a devastation in a Catholic country where being a homosexual is a mortal sin requiring repentance and conversion. Interestingly, he imagines Oscar Wilde encourages him by suggesting that the only way to remove temptation is by giving in to it.

In Doyle’s production the musical is streamlined to eliminate an intermission and keep it as one continuous series of events that move with swiftness, as players would effect their version of what happened, without including every detail. There are fewer players and most of them are incredible musicians that round out the small band tucked away in a second floor balcony against the back wall of the CSC playing area, where the audience abuts on three sides. Thanks to Bruce Coughlin (orchestrations), Caleb Hoyer (music director) Strange Cranium (electronic music design) the music arrangements, Doyle’s staging and the players’ vocal work is gorgeous, and seamlessly, perfectly wrought in configuring the St. Imelda’s Players’ production. Indeed, they are much better than they’ve jokingly been described.

After the turning point (“Love Who You Love” carries the theme) the players reveal that Adele can’t continue with her lines as Salome because the words convict her soul. She can’t act a role where she’s supposed to be innocent and virginal, because in real life, she’s a fallen woman, who had intercourse out of wedlock and now is pregnant. Full of guilt and remorse her punishment is self-torment and humiliation. She must emotionally suffer the rest of her life because abortion is out of the question and the father won’t marry her to make the baby legitimate. The church and the oppressive paternalistic folkways of the culture vilify her with unworthiness and condemnation.

Catholicism hangs over the heads of the characters like a dirge of annihilation and judgment. Adele will have to go home to receive help from her parents to raise the child. Meanwhile, Mr. Carney also uses religious folkways to shut down the play. To add insult to injury, Robbie feels condemned by Alfie when Alfie unwittingly interrupts Robbie and Mrs. Patrick (Jessica Tyler Wright) making love in the bus garage. Feeling the weight of the sin of adultery, Robbie insults Alfie and judges Alfie’s life is without love, an accusation that torments Alfie because he loves Robbie.

Alfie can never reveal this love to him because it would drive Robbie away. Though Alfie has attempted to confess to Father Kenny (“Confession”) he can’t bring himself to reveal his great sin and thus is damned with guilt. As a result of the conflict of loving someone who would never love him, and being accused by that same person as being unloving, Alfie throws caution to the winds. He engages with Breton Beret who has been waiting for the opportunity to make himself look like a real man by beating up a “poof.”

Clearly, the film (1994) was made at a time when the Catholic church was dealing with its own sexual sins which finally came to the fore in the world wide expose of pederasty in the church around 2002. However, the film/musical sets the events back in the 1960s before any of the cultural revolutions took place. Nevertheless, to understand the full force of Catholicism condemnation of homosexuality, check the numbers of gay men who were abused as Alfie is abused by the likes of Breton Beret, or look at the numbers of Catholic gay men committing suicide because they couldn’t reconcile their feelings with their religion. Also, read up on the Republic of Ireland’s approach toward girls who got pregnant out of wedlock in the book Philomena (also a fabulous film with Judi Dench). Or read the stories of the Magdalene Laundries, captured in the film The Magdalene Sisters. The brutality of the paternalistic Catholic folkways winked at male adultery like Robbie’s and swept it under the rug as “boys will be boys.” As for gays or women with babies born out of wedlock, the humiliation, shame and condemnation was a cruelty that destroyed lives.

In the book of the musical McNally is not heavy handed with Catholicism in its iteration at St. Imelda’s community church. The musical has a light touch and religion appears to take a back seat, if we are not aware of the entrenched history of the church and its devastation on its believers. Rather, it is understated with Robbie’s anger at being discovered by Alfie, and Adele’s tears when the father of her child abandons her after he takes what he wants. Alfie gets the worst of it because he is discovered as a homosexual by the police who come to save him from being beaten to death by Beret. But the rub is he can’t press charges for assault because public opinion against “poofs” is more reprehensible than a physical assault. In fact it is intimated that Beret gets backroom laughs and cheers for beating up a homosexual who fell for his enticement.

McNally, Flaherty and Ahren configure the church’s worst folkways to be the sub rosa driving force for all of the humiliation, self-condemnation and torment that makes the conclusion so incredibly vital to A Man of No Importance. Thanks to Doyle, the performers and the creative team’s talents, the conclusion is uplifting and poignant for us today with a message of love and acceptance that is never old. It is the true spirit of Christmas in this “Happy Holidays” season, and in the United States needs to be proclaimed from the rooftops. In its quiet and unassuming way, A Man of No Importance is a trophy winner.

Kudos to Ann Hould-Ward (costume design), Adam Honore (lighting design) and Sun Hee Kil (sound design) and the entire cast and creative team who bring Doyle’s vision to life. The excellent must-see A Man of No Importance is at CSC until 18 December. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.classicstage.org/current-season/a-man-of-no-importance

‘Camp Siegfried,’ a Review of the Second Stage Production

Did you know that in the 1930s the Nazis ran propaganda summer camps for youngsters, like the one in Yaphank, on Long Island New York and elsewhere across the United States? Camp Siegfried was created by the German-American Bund, led by Fritz Kuhn to sway various Americans to support Germany in its bid to overthrow Communism, Judism and “corrupt” liberalism in Europe and elsewhere in the world. Considering that there was a large German immigrant population in the United States, the Nazi Party’s idea of propagandizing United States German citizens toward the benefits of Nazism in support of Hitler’s Germany was a sound one.

Bess Wohl’s titular play about Camp Siegfried falls short of powerfully dramatizing the true nature and danger of such Nazi camps that were pro-Hitler retreats sponsored by German loyalists. Wohl’s Camp Siegfried, a two hander “romance among the Nazis” directed by David Cromer is currently running at 2ndStage with no intermission. Unfortunately, the production lacks dynamism, terror and moment in its attempt to reveal the gradual inculcation of Nazi doctrine in the minds of the protagonists.

Wohl’s attempt not to give too much away proves damaging to the overall impact of the play. What should be directly energized and dramatized in the Nazi Party’s will to dominate, never really comes across. The only time it does is when a speech is proclaimed by She (Lily McInerny’s graduated intensity works well) and only because of the added response to the speech. It becomes the high point because of canned cheering which increases as the venom and hatred increases in She’s speech, spoken in German. (There are no super-titles, so German is an imperative if you want to understand it.) But by the time that speech arrives, so much more could have been done to incisively reveal the sub rosa impact of the brainwashing on the teens that should be terrifying but isn’t. The play’s overall effect lands with a thud as do its themes which are muddled.

This camp and others in New York stoked the fervency for the 1939 Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden which was protested by those against Hitler’s fascism. The camps were considered egregious and they were shut down. Camp Siegfried’s propagandizing was greater than what Wohl’s play suggests in her attempt to portray the interactions between the teens. This is a missed opportunity especially for us during this time of growing white nationalism in our culture which needs to be called out for its violent hatefulness. Those who proudly display swastikas should not be greeted with smiles and pats on the back. Such acceptance is consent and grows toward hate crimes. And if the symbols of Nazism are understated, or treated as non existent as in Wohl’s play, that is an inconvenient misdirection. Not revealing the typical abundance of signage used by the Nazi Party loyalists in the US camps is questionable and removes the play’s chilling effect.

Hitler and Goebbel’s propaganda was steeped in occult symbolism. The Nazis believed in the power of the Swastika in their flags, insignias, their specially designed uniforms which conveyed “majesty” and fear in their intent to show dominance and preeminence. To suggest subtly how one might be seduced into wickedness without showing the associated “signs” of how that wickedness is conveyed is problematic. This is especially so when Camp Siegfried’s name is used, but the power of Nazi will and their purpose for the camp in this play, appears expositionally without menace until the very end, and as a result, seems random and confused.

The camp is seen through the perspectives of these teens as an OK place where they can have sexual fun, abuse each other verbally and physically and learn “stuff.” That they they are propagandized into one of the greatest, evil political belief systems of 1938 on the eve of Hitler’s invasion of Poland after annexing Austria is momentous. That sense of moment is intentionally mitigated because only part of the story at the camp is conveyed by the teens. For me, that is a weakness in the play’s structure in addition to its dependence, not on dramatic dialogue, but on exposition. Dynamic drama is missing. For example She’s visit to the doctor, if activated with an actual visit instead of as exposition, the weight of the camp’s abuse would be made more powerful by the doctor’s direct comments. Additionally, drama might have been conveyed via a different, more visceral examination of the camp reflected in scenic design and lighting design. Costume design and sound design succeed best at conveying the sinister symbols of Nazism at the camp but only during She’s speech and in He’s costume after he joins her when she is finished.

Depending upon the resources one looks up, in 1938 in this camp and others, those at the camp dressed in Nazi uniforms and drilled military-style with marching, inspections, and flag-raising ceremonies. Swastika flags were situated next to the American flag. However, since Wohl’s play involves a two character limitation of the nameless He (Johnny Berchtold) and She (Lily McInerny), there are no other “campers” to show this “glory” of Hitler that the camp Nazis uplift. There are no portraits of Hitler, though there supposedly were at the real camp.

We only see the camp exterior. Brett J. Banakis’ scenic design creates the naturalistic set of a hillside and wooden fence-like wall abutting the camp. When He and She put together a platform that is later used for She’s speech, there are no swastikas, pictures or flags draping it, though there is canned cheering. The effects of what the climax of that speech might have been thematically and viscerally are diminished because the key symbolism of Hitler’s Nazi propaganda is absent. A sinister aspect is only suggested in the canned cheering in what sounds like a Nazi rally in 1930s Germany.

In Wohl’s Camp Siegfried, much is expositional; much is ancillary. We hear Hitler and Goebbel’s names mentioned as streets in the camp. We hear that the teens must do the work and if they are injured, they must suffer through it and be strong. She discusses the symbolism of the name Siegfried which she has learned and she tries to learn German. He chops wood for the all night bonfires; no workers from labor unions are allowed as unions were thought to have Jews (a reference He makes). The discriminatory aspects of this are downplayed. As he chops wood they get to know one another and more things are revealed about the camp. For example She reports various girls brag about having sex with specific boys.

That the young men and women are being encouraged to “breed” and create Aryan replicas is unconnected to Nazism and the import of the activity is skewed. In one segment while He masterbates masochistically, She sadistically belittles and demeans him to be worthless. Their activity is disjointed and we are led to believe that their behavior isn’t connected with what the intentioned propaganda of the camp toward young men and women is. In some scenes after they couple, She demonstrates pride in telling He about her pregnancy. Her pregnancy is a lie, learned propaganda and manipulation. Wohl’s He and She fall in line with the learned camp behaviors out of gross inferiority and shyness. However, the characters are shallowly drawn and lack emotional grist. They are not easy to empathize with and thus, their indoctrination has less of an impact on the overall themes and conclusion which ends hollowly.

In the source material Camp Siegfried’s grounds had Nazi and Hitler Youth flags and pictures of Adolf Hitler. Men were photographed in uniforms (Italian Fascist-style blackshirts, SA-style brownshirts and Nazi military uniforms. It is arguable whether it is more frightening to see a sexual relationship between two teenagers budding against a background of Nazi flags whipping in the wind next to American flags, or an absence of them as if they don’t exist. However, in their absence, the danger and horror of what Camp Siegfried symbolized for that time and what its exploration through the teens’ eyes intimates for our time is lessened to the point that one wonders why the titular camp was selected and its purpose downplayed as an artifice. There is no visceral imagery or camp life that is believable and too much exposition gets in the way of the dynamic dramatic.

When He and She first meet on a back wall of the camp hillside, He tells She about the camp activities which include marching. If the “power” and “glory” of Hitler’s propaganda spectacle was manifest each day with the signage and Swastika flags, without learned revulsion, then Nazification would have drawn He and She in large part through the spectacle of such symbols that the adults at the camp salute to and venerate. But that which was a huge part of the symbolism used to bring unity, awe and fear by the Nazi Party and German loyalists, who use the camp to train future Nazi leaders, is absent. The audience is never allowed in to the camp and what they hear isn’t enough to make a difference because it is never activated or visualized.

The only events actualized concern their sexual relationship, the wood chopping, the platform building and the speech. All should have more than a slim thread of the Nazi connections but they don’t until the last two minutes of the play and only through exposition. Otherwise this would be a typical summer camp (it isn’t). We follow two teens (the actors in their Broadway debut make the best of their roles) and their relationship. She gives a speech with a Nazi salute that reveals her indoctrination. And the purpose of the camp is revealed with her description of what she’s been through to the doctor. We only find that out because she tells He.

Wohl conveys the focus of the camp in a gradual sub rosa way via exposition and He’s behaviors. Unconnected to the other camp members or activities, the action is unclear as to the extent it is unfair and cruel (until at the conclusion She reports how the doctor defined what happened at the camp as a delusion). Likewise, another activity He engages in is archery. But its importance as potential discipline and military training is muted as are all the actions we see the teens undertake. However, in reality camp activities are organized to make future Nazi leaders in the US to run for political office, to unify German Americans, and place them in leadership roles to dominate in coherence with Hitler’s Third Reich.

This is hinted at via exposition and reportage at the end of the play when She reports to He that she went to a doctor outside the camp after He has beaten her badly. When she tells the doctor why she’s so cut up, revealing the camp’s abusive treatment in addition to He’s beating, the doctor (an outsider) tells her, “Anyone can be seduced.” And he follows this with, “Never underestimate your infinite capacity for delusion.” As she reports this to He, the spell is broken. She tells He they were both caught up in the delusion. He doesn’t accept what she says and tells her that Herr Kuhn has invited him to Germany and he will meet the higher ups and join the “worldwide fight.” This important scene with the doctor is reduced to exposition, yet it is what changes her mind about the camp.

Anything that might strike horror for us today is not shown. This seems misguided and changes the thrust of the play, whitewashing it. There is nothing benign about a Nazi Swastika flag next to the American flag which was pictured at the real Camp Siegfried. The play’s camp carries the title, but the substance and meaning are squeezed out of it. Thus, the lure of the propaganda which should be terrifying to us because we know what is behind it, never finds emotional power or effect. The forward movement becomes some teens playing at sex and being adults and searching out each other with a backdrop at a camp that we hear appreciates the Nazi Party, Hitler, teaches German, has all-night rallies and marches. The culmination occurs when She delivers a speech and lifts her hand in the Sieg Heil salute and feels pleased with herself but reverses after her discussion with the doctor.

It may be horrific to have a Nazi Swastika onstage with other Nazi paraphernalia, but that horror is real and signifies something beyond just the freedom to express it. More might have been done to reveal the iconography of the Nazi party that was propagandizing the teens at the camp since it was such iconography that swelled German pride during that period of time in Germany and during the 1939 Nazi Party rally at Madison Square Garden.

Thus, the play never rises to the dramatic moments of danger and fear that Wohl might have brought to bear during our time that again sees the rise of white nationalism in our country, and on Long Island. There, on Long Island, the KKK, confederate flags and white nationalistic Holocaust Denier T-Shirts have been seen in allegedly patriotic parades and boat regattas supporting Donald Trump, a proponent of White Nationalism (think Nazis) and anti-democratic insurrections. Not to include the symbols or uniforms as they were used at the real Camp Siegfried, when white nationalism threatens our very democratic institutions is problematic.

At the Capitol on January 6th, there are pictures of Holocaust deniers proudly wearing T-shirts proclaiming that 6 million more should have been killed. This occurred during an insurrection that intended to nullify our constitution and install a despotic, white nationalist, who decries not indecency, bigotry, anti-semisitism, racism and hatred, but anyone who criticizes him. This is a time when a known Holocaust denier went to Mar-a-Lago, a few days ago, the place once referred to as the Southern White House. Actions and words carry great meaning.

The Nazis gently referred to and mildly presented in this play via exposition were essentially absent. Especially absent are key symbols of Nazi propaganda that the Nazi Party used for their potent and clever manipulation to sway the minds of Germans. Their non-appearance in the play is definitely a teachable moment. Likewise, the decision to omit these dramatic elements carefully constructed by the Nazi Party to excite and unify, in a play about Nazi allurements, also is a teachable moment. Their absence is silence.

Camp Siegfried runs with no intermission at https://cart.2st.com/events

‘Evanston Salt Costs Climbing,’ Arbery’s Excellent Play is a Must-See

In the microcosm is the macrocosm. This is especially so in the setting Will Arbery presents in Evanston Salt Costs Climbing, the sardonic, metaphysical-realistic 95-minute play acutely directed by Danya Taymor, currently at the Signature Theatre presented by The New Group.

A key theme of Arbery’s exceptional work turns on the notion that the larger picture of what is happening resides in the details which human beings have a penchant for ignoring, though it is right before their eyes. Do we see the connections, or are we like the characters in this play, willfully unaware until a catastrophe results and it is too late to do anything about it? Arbery examines these themes in his thought-provoking, stylized work that suggests we cannot escape how we relate to our environment, no matter how much we attempt to obviate it. Indeed, Arbery points out that it is this blindness that has brought us to the brink of self-annihilation. Ironically, even standing on the brink looking down, we can’t manage to do what is needed to confront the human disaster that is unfolding before our eyes.

At the opening of Arbery’s play two truck driver forty-somethings, Peter (the superb Jeb Kreager), and Basil (Ken Leung is his vivacious side-kick), share their morning coffee before they take their rounds spreading salt to safe-guard the roads in and around Evanston, Illinois. We let this information slide away from us without giving it much thought. However, everything in Arbery’s play is profound and the characters’ lives and future are encompassed in the smallest detail of salt spreading. In that detail is reflected the wider invisible world that the characters sense is out there, both under the ground, pushing to break apart the sham infrastructure that cities have built for the purpose of commerce, or in the invisible world that hangs above in the ambient atmosphere pressing down on the characters to confound them and make them despondent.

The world that Arbery’s characters inhabit is representational. The action takes place in the environs of the Evanston “salt dome,” in the truck, and in Maiworm’s home, all staged with superb and symbolic minimalism by Matt Saunders’s scenic design, Isabella Byrd’s lighting design and Mikaal Sulaimon’s sound design. Before Peter and Basil begin their shift, Maiworm, the public works administrator who is their boss (the excellent Quincy Tyler Bernstine), stops in as she does each morning. Maiworm is astute and stays on top of the forward moving trends regarding the Green Movement. She understands the “larger picture” of the changing environmental conditions which impact their jobs and of which Peter and Basil remain unaware. Maiworm attempts to enlighten them by reading an article to them, the gist of which states that the record colder temperatures are requiring record levels of salt use. These are driving up the salt costs.

If we are paying attention, we understand the cause and effect of global warming and weather weirding indicated in this small detail of salt costs. After Maiworm reads the article, Peter says an article should be written about the fun he has with Basil driving in the truck. He doesn’t catch the “devil” in the details. In other words, he never makes the leap that the costs might impact his current job, his hours or salary. He assumes all will remain static in this job he’s had for twenty years.

Basil, who writes micro-fiction, ignores the underlying significance of the article for another reason. He tells Peter no one wants to read an article about their job because it has no “pull” or interest. The connection between Arbery as a writer and Basil is understated. It is as if Arbery twits himself about the intentional boring context of “salt costs climbing,” knowing that such a subject will not keep the audience engaged. However, Arbery is having us on. That is not what the play is about. And how the playwright cleverly connects this “detail” with its hidden significance making it dynamic and indelibly related to his characters is striking and horrifically revelatory to us.

Basil asks Maiworm about the impact of the increasing salt costs. Arbery reveals why Basil asks the question in the next scenes when we see that he and Maiworm have developed a covert sexual relationship unbeknownst to Peter. Thus, unlike Peter who doesn’t see or care about the symbolism behind the details, Basil is open to Maiworm’s thoughts and most probably encourages the direction of her decisions to feather her own nest and advance in her administrative position which must take into consideration the budget which includes the price of salt. However, on another level, he too misses the significance connecting the dots to climate change and colder weather which will create havoc if the powers that be (including Maiworm), don’t properly plan for it.

In a humorous scene that follows, we understand why Peter loves driving in the truck with Basil. They act silly and ridiculous, sharing “manly” antics as “roadies,” who do their job and maintain a friendly relationship, where they can cut loose and have a free-for all (which mostly entails cursing). Also, during this time Basil and Peter discuss more personal issues. Basil relates the dream he has of his grandmother who has told him, “Don’t let the Lady in Purple come near you.” He states, in the last part of the dream, The Lady in Purple does come near his grandmother, who dies. We intuit that the Purple Lady may be Death.

Additionally, Basil discusses that he ends up fusing with the Purple Lady and reverts to a dying little boy as the Purple Lady takes him. This, he tells Peter, happens during a time when cities are freezing and burning. Basil’s description is metaphoric and prescient in its representation of global warming, which he never mentions by name as if it doesn’t exist. By degrees, Arbery reveals how the events Basil describes in the dream come to fruition in his life in a mysterious way that merges phantasmagoria with reality later in the play.

Peter expresses that he is sad and his dreams are surrounding darkness and noise. This reflects Peter’s depression and suicidal thoughts. Basil, who has discussed Peter’s wanting to kill himself and kill his wife is concerned that Peter is in bad shape. Basil tells Maiworm about Peter and she vaguely comments she’ll watch out for him.

The dynamics of the interrelationships complicate as we learn more about Maiworm’s adopted daughter, Jane Jr., who suffers from depression and has suicidal thoughts like Peter. As Jane Jr. Rachel Sachnoff gives a fine, nuanced performance. of the only character who understands the impact of climate change. Maiworm’s concern for Jane Jr. includes trying to direct her interests by getting her to read Jane Jacobs’ book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Additionally, Maiworm encourages Jane Jr. to help others by singing to them at the nursing home. To make her feel needed, Maiworm uses Jane Jr. as her confidante. After a nightmare provoked by the suicide of the journalist who wrote the article Maiworm reads to Peter and Basil, Maiworm discusses her anxiety about Evanston. Maiworm tells Jane that she saw the dead rise from under the ground as the journalist fused with them. Then she segues the discussion to heated permeable pavers, the technology to make roads heat up so they can melt ice and snow to eliminate the use of salt and reduce costs.

Like all exceptional playwrights, Arbery reveals the trenchant themes by gradually through their connections. Eventually we learn one aspect why the heated permeable pavers might be a great solution. The salt is incredibly toxic and destructive to wildlife. Salt run-off pollutes the water table creating toxic blooms releasing poisonous chemical compounds and metals that kill animals and people.

Interestingly, this is the first we hear of such a technology, but not the last. We discover much later when Arbery connects the dots that Maiworm, to advance in her position, is part of the program to bring heated permeable pavers to Evanston, unbeknownst to Peter and Basil, whose jobs will become obsolete as a result. However, the implications of this Arbery does not make “visible” until after personal devastation occurs to each of the characters over the course of the three consecutive brutal winters in Illinois when the play takes place.

Arbery boxes in the characters who increasingly become dislocated through sadness and depression, indirectly caused by ignoring the moment of what is happening around them in the environment. Arbery indicates that though they don’t see the larger picture of the apocalyptic effects of climate change, in the unseen realm of the invisible world, it impacts them day and night. Jane Jr. is aware of this. It is mostly the cause of her depression and desire to end her life. She considers her Dad lucky that he died and doesn’t have to experience the impending doom that can be felt everywhere. Maiworm and others go about their lives as if nothing is happening. They live in a denial and that doesn’t quite work because they sense the coming destruction but don’t articulate its connection to what they feel is happening. Articulation is the beginning of recognition.

The unseen doom disturbs everyone. Peter’s suicidal thoughts continue and his situation worsens after his wife dies from an accident on the icy roads that didn’t have enough salt on them (presumably because less salt was used to defray costs). Fortunately, his daughter lives and they bond over Dominoes Pizza and watching the truck come to their door, a fun event for the six-year-old. Their relationship is the bright light in the play.

Maiworm’s guilt about Peter’s wife’s death is understated, but her behavior becomes more hyper and the overarching doom she senses increases in her life with Jane Jr. Additionally, the doom is in Basil’s dreams and shows up in his micro-fiction. When he is confronted with his past and inability to deal with it in his present, he is swallowed up (the Purple Lady makes an appearance). Basil joins the other dead in the earth metaphorically and physically fulfilling his nightmares. How Taymor and her team effect this is strange and dislocating, intensifying the play’s foreboding which becomes palpable to the audience.

Maiworm who could understand the impending doom of global warning’s impact on their lives, can only manage to live in the microcosm to fulfill her desire for advancement. She is the most blind and she blindsides others. Palliative measures to correct the dire future with “heated permeable pavers,” are too little too late. Caught up in the details, she ignores the “bigger picture.”

The climax of the encroachment of the unseen (the environment rebelling), upon the characters occurs toward the end of the play where Arbery delivers his key message delivered by a supernatural incarnation of a presence from the past, Jane Jacobs. As Jacobs, Ken Leung arises in black funereal dress. Without his accent he comes across with clear, precise anger and a clarion warning. Jane Jacobs suggests what we must do as human beings to face the oblivion of our own making. See the play; there is no spoiler alert.

Taymor’s direction of the actors is spot-on as they convey the suppressed doom in the tension and growing personal alarm in their dreams and confessions. All of the creative artists majestically bring together Arbery’s and Taymor’s vision of the dire consequence of the environment rebelling as an incarnate “thing.” Saunders, Byrd, Sulaiman and Sarafina Bush’s costume design, help to manifest terror in the atmosphere of the play through the suggestions of mysterious other-worldiness peeking through reality. We “get” the palpable danger human beings have created for themselves with their willful ignorance, negligence and dereliction of duty. That danger drives Maiworm, but because she ignores the signs and can’t translate what she feels into understanding, her obsession is misdirected. Caught up with the pavers for the future, Maiworm forgets to order salt for the present winter and they must hire others to do the job of salting the roads. She is rewarded for her incompetence as her advancement continues up the administrative chain.

The director and her team use at varying intensities darkness, shadows and light to great effect. Additionally, they alternate silence and loud sounds of the truck engines, screeching tires and grating sounds made by the raising and lowering of the warehouse garage doors. They employ storm sounds as well. These help to enhance the ominous atmosphere the characters feel and creates in us a growing dread. Also, the use of lighting and sound suggest the extremes of heat and cold and the eerie, weird quality of the environment as a being which humanity has monstrously shaped by its abuse. As a result of Taymor’s direction, Saunders, Bush, Byrd and Sulaiman’s artistry the nameless stark, terrible becomes real and the playwright’s themes hit home. Their prodigious efforts combined with the actors’ authenticity create memorable live theater that should not be missed.

For tickets and times go to their website https://thenewgroup.org/production/evanston-salt-costs-climbing/

‘Catch as Catch Can’ Review