Category Archives: NYC Theater Reviews

Broadway,

Mary Louise Parker, David Morse Renegotiate Their Roles in the always amazing ‘How I Learned to Drive’

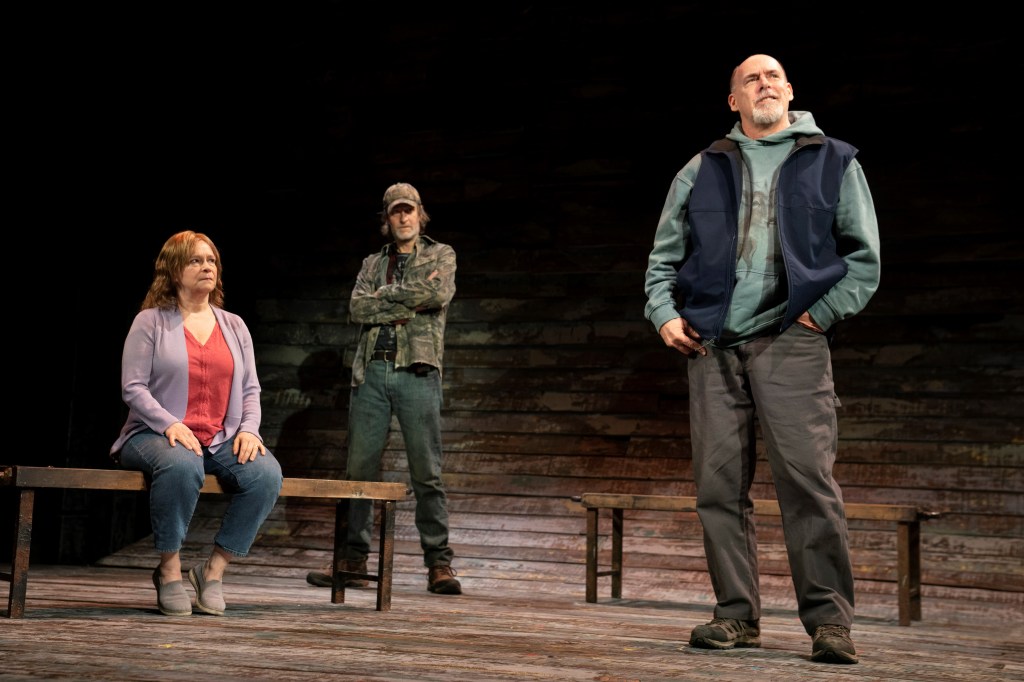

Paula Vogel’s Pulitizer Prize winning How I Learned to Drive in revival at the Samuel Friedman Theater is a stunning reminder of how far we’ve come as a society and how much we’ve remained in the status quo when it comes to our social, psychological, sexual and emotional health, regarding straight male-female relationships. Pedophilia and incest by proxy are as common as history and not surprising in and of themselves. On the other hand how particular male and female victims lure each other into illicit sexual self-devastation is unique and horrifically fascinating.

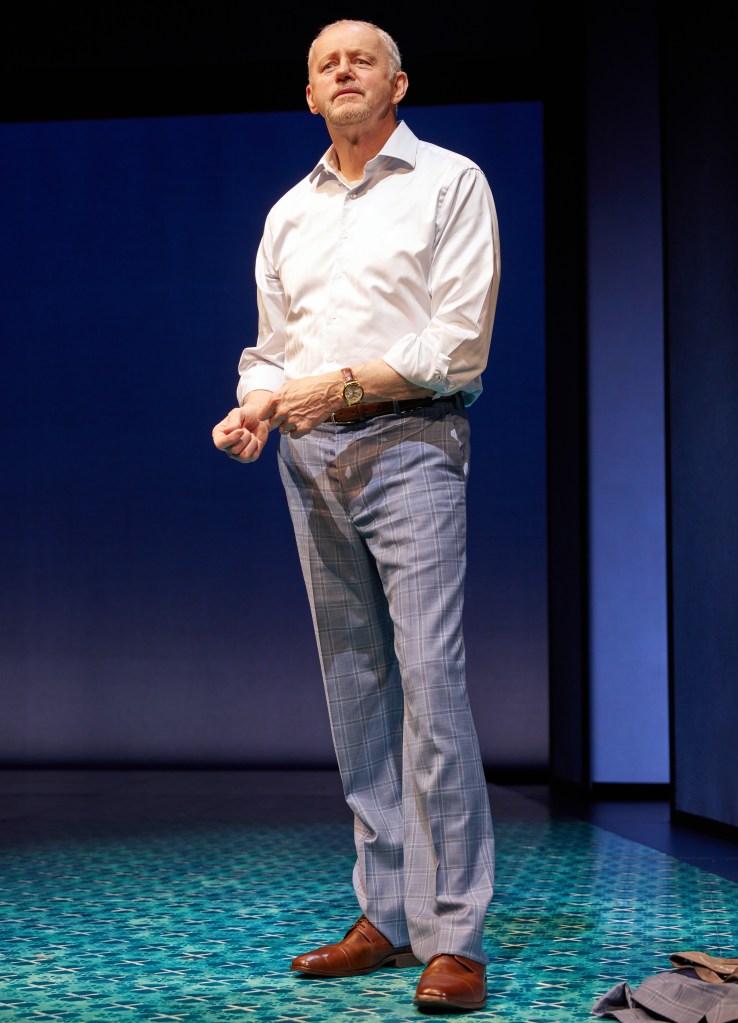

This is especially so as leads Mary-Louise Parker, David Morse, and director Mark Brokaw put their incredible imprint on Vogel’s trenchant and timeless play. Interestingly, Parker and Morse are reprising their roles from the original off-Broadway production, with original director Mark Brokaw shepherding the Manhattan Theatre Club presentation. Parker (Li’l Bit) and Morse (Uncle Peck) are mesmerizing as they portray characters who manipulate, circle and symbolically search each other out for affection, love and connection. The relationship the actors beautifully, authentically establish between the characters is heartbreaking and doomed because it cannot come out from under the umbrella of the culture’s changing social mores, Peck’s psychological illness from the war, and Li’l Bit’s familial, sexual psychoses.

How I Learned to Drive reveals what happens to two individuals (a teen girl and an adult male), who engage in the dance of psycho-sexual destruction while negotiating feelings of desire, love, attraction, fear and guilt under society’s and family’s repressive sexual folkways and double standards. What makes the play so intriguing is not only Vogel’s dynamic and empathetic characterizations, it is her unspooling of the story of the key sexual-emotional relationship between Li’l Bit and Peck.

Li’l Bit and Peck’s relationship is not easily defined or described as sexually abusive, though in a court of law, that is what it is, if an excellent prosecutor makes that case in a blue state. However, in a red state, it might be viewed differently. Consider 13 states in the US allow marriage under 18, and Tennessee has recent records of marriages of girls at 10 years-old with parental or judicial agreement.

Sexual abuse, if the players are amenable and influencing each other for reasons they themselves don’t understand, is a slippery slope depending upon the state’s political and social folkways, the familial mores and the perspectives of the players themselves. Ironically and eventually, a turning point comes IF the abuse is recognized and the relationship ends whether exposed to the light of public scrutiny or not as in the case of Lil’Bit and Peck.

In Vogel’s play, how and why Lil’Bit ends her forbidden relationship with Uncle Peck is astounding, if one looks to Vogel’s profound clues of Lil’Bit’s emotions which are an admixture of confusion, regret, love, affection, annoyance, fear and disgust of going legal/public and against family, for example, her Aunt, whom she has “stolen” Peck from. Indeed, Lil’Bit is willing to forget what happened and stop their secret “drives” after she goes away to college. But when she is disturbed by Peck’s obsessive letters, and drinking to excess, she flunks out. She is haunted by the events (sexual grooming in 2022 parlance), that began when she was eleven, so she ends “them.” The last time she sees him is in a hotel room, though at 18-years-old she is of age and old enough for intercourse under the law. However, she must be willing.

Her ambivalence is reflected when she lies down with him on a bed, obviously feels something but gets up. Yes, she agrees to do that after she has two glasses of champagne. But when he asks her to marry him and go public with their affection with each other, it’s over. The irony is magnificent. When they were secret, she let it happen and told no one and continued her drives with him until college. The public exposure of a public marriage is loathsome for her as she would have to confront what has transpired between them for seven years.

As Vogel relates the process through Lil’Bit’s sometimes chaotic flashback/flashforward, unchronological remembrances, we understand the anatomy of Peck’s behavior and hers. The finality of this revelation occurs when she divulges the precipitating abusive event on Lil’Bit’s first driving lesson in Peck’s car. Driving becomes the sardonic, humorous metaphor by which Peck reels her in, linking her desires to his (part of the affectionate aspect of grooming). Her mother (the funny and wonderful Johanna Day), despite negative premonitions, allows her eleven-year-old to go with her uncle, though she “doesn’t like the way” he “looks” at her.

The dialogue is brilliant. Li’l Bit chides her mother for thinking all men are “evil,” for losing her husband and having no father to look out for her, something Uncle Peck can do, she claims. Li’l Bit uses guilt to manipulate her mother to let her go with him. Her mother states, “I will feel terrible if something happens” but is soothed by Li’l Bit who says she can “handle Uncle Peck.” The mother, instead of being firm, says, “…if anything happens, I hold you responsible.”

Thus, Li’l Bit is in the driver’s seat from then on, responsible for what happens in her relationship with Peck, given that warning by her mother. This, in itself is incredible but the family has contributed to this result in their own personal relationships with each other as Vogel reveals through flashbacks of scenes which have psycho-sexual components between Peck and Lil’Bit and Lil’Bit and family members. However, this is a play of Lil’Bit’s remembrance. We accept her as a reliable narrator, knowing that things may have been far different than what she tells us. As she is coming to grips with what happened to her as a child, we must admit, it could have been worse, or better, any of the representations less or more severe. Indeed, she is narrating this story of her teen years as a 35 or 40-year-old who is plagued by the tragedies of the past which include what happens to her Uncle which she may feel responsible for.

During the flashbacks which are prompted by themes of unhealthy sexual experiences (including male schoolmates’ obsession with her large breasts), Lil’Bit reveals prurient details about her family’s approach toward their own sexuality and hers. It is not only skewed, it is psychologically damaged. For example, Lil’Bit explains they are nicknamed crudely and humorously for their genitalia. Her grandfather represented by Male Greek Chorus (the superb Chris Myers), continually references her large breasts salaciously, one time to the point where she is so embarrassed she threatens to leave home. Of course, she is comforted by Uncle Peck who understands her and never insults or mocks her. However, in retrospect, he does this because it’s a part of their “close” driving relationship.

In another example her mother chides her grandmother for not telling her about the facts of life because she was most probably gently forced into sex, got pregnant, had a shotgun wedding and ended up in an unhappy, unsuitable marriage. From the women’s kitchen table of women-only sexual discussions, we learn that grandmother married very young and grandfather had to have sex for lunch and after dinner, almost daily. And with all that sex, grandma never had an orgasm.

When Lil’Bit asks does “it” hurt (note the reference isn’t to love or intimacy or even the more clinical intercourse), the grandmother portrayed by the Teenage Greek Chorus (Alyssa May Gold who looks to be around a teenager), humorously tells her, “It hurts. You bleed like a stuck pig,” and “You think you’re going to die, especially if you do ‘it’ before marriage.” The superb Alyssa May Gold is so humorously adamant, she frightens Lil’Bit so that even her mother’s comments about not being hurt if a man loves you are diminished. Indeed, reflecting on her mother’s unwanted pregnancy and her grandparents’ cruelty forcing her mother to marry a “good-for-nothing-man,” the discussions are so painful Li’l Bit can’t bear to remember their comments “after all these years.”

Thus, romance, love and affection and sweet intimacy are absent from most discussions about men who are neither sensitive, caring, loving or accommodating to her mother (an alcoholic with tips on drinks and how to avoid being raped on dates), and grandmother who never had an orgasm with her beast-like husband. Only her Aunt seems satisfied with Uncle Peck, who is a good, sensitive man, who is troubled and needs her, and who reveals that she sees through Li’l Bit’s slick manipulation of him. She knows when Li’l Bit leaves for college, her husband will return to her and things will be as before. An irony.

Vogel takes liberties in the arc of the flashbacks with intruding speeches by family. As all memories emerge surprisingly when they are disturbing ones, Li’l Bit’s are jumbled. The exception is of those memories which organically spring from the times Peck and Li’l Bit drive in his car as he teaches her various important points and helps her get her driver’s license on her first try. After, they celebrate and he takes her to a lovely restaurant and she gets drunk.

Again and again, Vogel reveals Peck doesn’t want to take advantage of her because he will not do anything she doesn’t want him to do, he proclaims. Thus, his attentions are normalized. And Lil’Bit shows affection yet, at times apprehension, ambivalence and acceptance. On their drives, Peck has become her quasi father figure, a confidant and supportive friend. Thus, she accepts his physical liberties with her (unstrapping her bra, etc).

Because the scenes are in a disordered cacophony, each must be threaded back to the initial event of Peck’s molestation which happens at the end of the play. SPOILER ALERT. STOP READING IF YOU DON’T WANT TO KNOW WHAT HAPPENS.

The mystery is revealed why Li’l Bit continues her driving lessons until she goes to college, and even then ambivalently meets him in the hotel room where he proposes. When she is eleven (Gold stands off to the side reminding us of her age as Parker and Morse enact what happens), she touches Peck’s face as she sits on his lap. While driving, Peck touches Li’l Bit who cannot reach the breaks, but only holds her hands on the wheel so she doesn’t kill them both. Though she accepts what he does initially, then tells him to stop, he ignores her. Then she states, “This isn’t happening,” making the incident vanish, though it happens. And she tells us, “That was the last day I lived in my body.”

It is a shocking moment and is a revelation at the play’s near conclusion. Prior to that Morse is so exceptional we take Peck at his word, that he won’t do what she doesn’t want him to. In the last scene, we see he lies. Likewise, we realize the impact of his horrific behavior on Li’l Bit. When she is twenty-seven as an almost aside, in the middle of the play, she cavalierly tells us she had sex with an underaged high school student, then reflects upon her experiences with Peck. She realizes for Peck, as for herself, it is the allure of power, of being the mentor and teacher to someone younger, using sex to hook them like a fish.

By this point, we have learned that Uncle Peck became alcoholic, lost everything and died of a fall seven years after she never saw him again. At this juncture in her life, perhaps she is reconciling and working through all of those traumatic experiences growing up. And then Lil’Bit tells us of her love of driving as she gets into a car and Peck’s spirit gets into the back seat and races down the road with her as the others stand outside and watch. Indeed, taking Peck with her, the damage is everpresent. Though she will never die in a car, she has learned to destroy others with the driving techniques of allurement, denial and “gentle affection” Peck showed her.

The actors do admirable justice toward rendering Vogel’s work to be magnificent, complex and memorable. With her profound examination via Li’l Bit’s remembrances, we see Parker’s and Morse’s astonishing balancing act inhabiting these characters and making them completely believable and identifiable. The audience tension is palpable with expectation as we become the voyeurs of a slow seduction: we wonder if the cat who mesmerizes the bird will really pounce or the bird merely enthralls the cat, knowing its wings enables it to an even quicker escape, leaving the cat in devastation of its own faculties.

Rachel Hauck’s minimalist set is suggestive of memory without a conundrum of details, just the bare essentials to fill in the locations with the time stated by the chorus (Johanna Day, Alyssa May Gold, Chris Myers). The depth and sage layering of Vogel’s production envisioned by Brokaw disintegrates the superficiality and sensationalism of pundits on the left in #metoo and on the right with #QAnon pedophile conspirators. It echos the tragedy of the human condition and the revisiting of the sins upon each generation who dares to breathe life into the next set of progeny.

Kudos to the creative team Dede Ayite (costume design), Mark McCullough (lighting design), David van Tieghem (original music and sound design), Lucy MacKinnon (video design), Stephen Oremus (music direction & vocal arrangements). This is another must-see with this cast and director who have lived the play since before COVID. You will not see their likes again. For tickets and times go to https://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/shows/2021-22-season/how-i-learned-to-drive/

Debra Messing in ‘Birthday Candles’ brings a tasty treat to Broadway

Birthday Candles by Noah Haidle, directed by Vivenne Benesch allows Debra Messing to shine as the aging Ernestine who moves from 17 to 107. As she traditionally bakes her birthday cake, over the years, first taught by her mom Alice (Susannah Flood), she gradually understands that she can only realize her dreams by being herself. And all along, getting married, raising a family, getting a divorce and finding the love of hr life, she has achieved her goal, taking her rightful place in the universe.

Haidle’s Birthday Candles, at the Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre, is poetic and complex with multiple themes. The most salient one focuses on Ernestine’s spiritual journey as the “every woman” sustaining emotional pain, trauma, loss, moving from weal to woe and finally reconciling a belated love with great joy in her 80s. As she moves quickly through time, she “looks through a glass darkly” without understanding, until she finally accepts the love and divinity in herself in her relationships with her family and partners. By her 107th year, she misses everyone and wishes them back as she has each time she gives the one passing (mother, daughter, son, grandchildren, etc.) up to the cosmos. Finally, her family spiritually appears and it would seem waits “in the wings” for her to accompany them on the next leg of her journey with them.

Haidle’s conceit about time and life’s passage in the “twinkling of an eye” (in the play 90 years in 90 minutes with some decades speeded up and others truncated) is most wonderful holistically as the characters live in the moments which they can’t fully appreciate. In this play the adage “life is short” is on steroids. Indeed, living one’s life while observing it alters it (a very rough comprehension of the Uncertainty Principle).

Thus, dramatically the play magnifies each character, present in their most vital of moments with Ernestine to heighten her life’s purpose in being herself, a mosaic of moments which come together at the conclusion. It is then that the audience and Ernestine reflect upon her life’s work and the revelation of Ernestine’s beauty is clarified. Of course, at that juncture when her work is finished, she moves to another realm in the starlit space/time continuum.

With the exception of Messing’s Ernestine, the actors portray multiple generationaly linked roles from mother Alice (Susannah Flood), to great grand daughter Ernie (Susannah Flood) with husband Matt (John Earl Jelks), son Billy (Christopher Livingston), daughter (Susannah Flood), grandchildren and forever sweetheart Kenneth (impeccably played by Enrico Colantoni). All these escort Ernestine through the years.

The dialogue and sounding of a bell for the passage of time clues us in to each generation as they come to celebrate Ernestine’s birthday while she bakes her plain butter cake over the 90 minutes of the play. Though birthday candles are never placed on top of the cake, nor is it iced, the title is enough. Indeed, Messing as Ernestine is both the icing and the candles, her soul and spirit, which are invisibly lit for eternity.

Importantly, every word of the dialogue is paramount and must be heard to appreciate Haidle’s depth of meaning, the poetry, the wisdom, the beauty and the sweet golden threads that bind from one generation to the next. In the performance that I saw (Wednesday evening), sometimes the dialogue was muffled and the words, not projected, slung together like a nondescript house salad without dressing. This was tragic because Haidle’s play is brilliant and achingly timeless and heartfelt. The humor is multi-layered and ripe. The conflicts which (if the actors don’t enunciate precisely) appear rather sparse. However, upon review, they are exceedingly well drawn and acute in each twinkle of time over the fast procession of years that transpose and spool Ernestine’s life.

Messing who is an accomplished TV (“Will & Grace”), film (The Mothman Prophecies) and stage actress (Outside Mullingar) is in her glory onstage throughout with “no rest,” (a meme in the play), a veritable tour de force. She is strongest and most poignant in the section of the play when Ernestine reaches a ripe seventy. She has negotiated life on her own terms, has become an entrepreneur, traveled to far flung places and is only taking care of herself. It is then when her granddaughter Alex (Crystal Finn) introduces the next surprising chapter in her spiritual evolution and she learns about reconciliations and renewals, and the fruition of faith and love.

Enrico Colantoni and Messing create the emotional grist for this section of the play which brings a sigh of relief to audience members and shouts from her children. They are truly stunning together and force us to look at those elements that Haidle insists upon in Birthday Candles, the spiritual, the ineffable, the timeless, the eternal. Their relationship which has been growing unseen for Ernestine, always felt to Kenneth, is breathtakingly conceived by the playwright, authentically manifested by Messing and Colantoni. It is the high-point, and Haidle has cleverly made us wait for it, so when it comes we are happily stunned and gratified.

Kudos to the cast when they projected (Colantoni and Messing had no problem) and the creatives: Christine Jones (set design), Toni-Leslie James (costume design), Jen Schriever (lighting design), John Gromada (sound design), Kate Hopgood (original music).

Birthday Candles is on limited engagement. See if before May 29th when it closes. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2021-2022-season/birthday-candles/performances

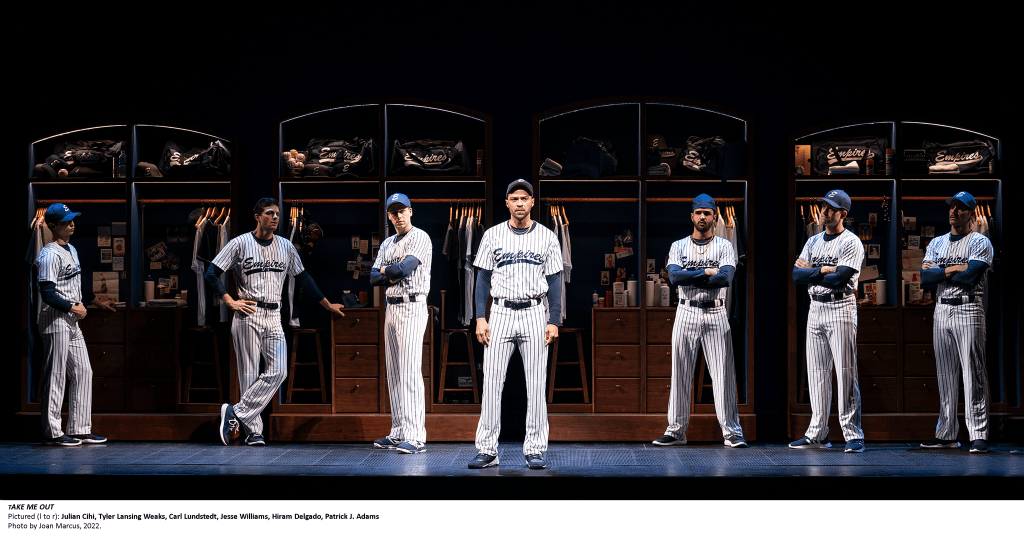

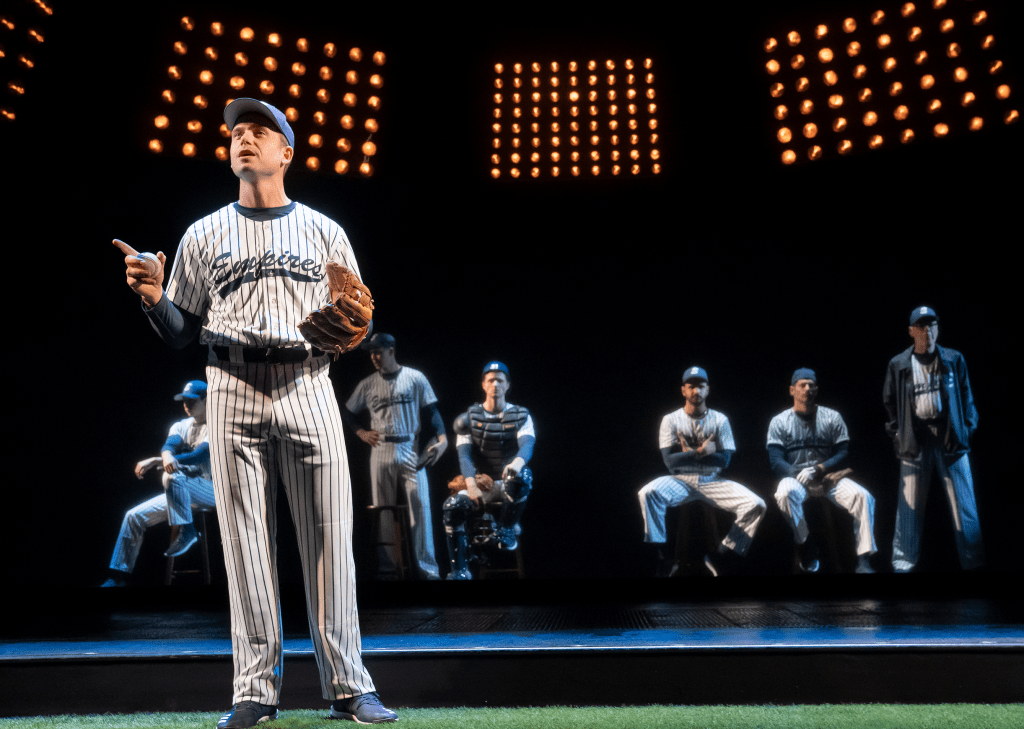

‘Take Me Out,’ the Revival Strikes Deep With Bravura Performances by an All-Star Cast

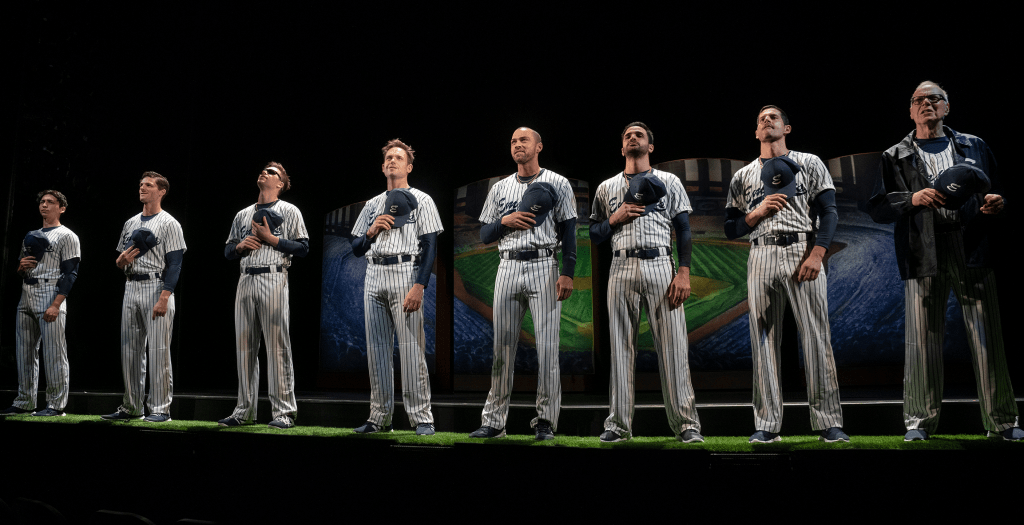

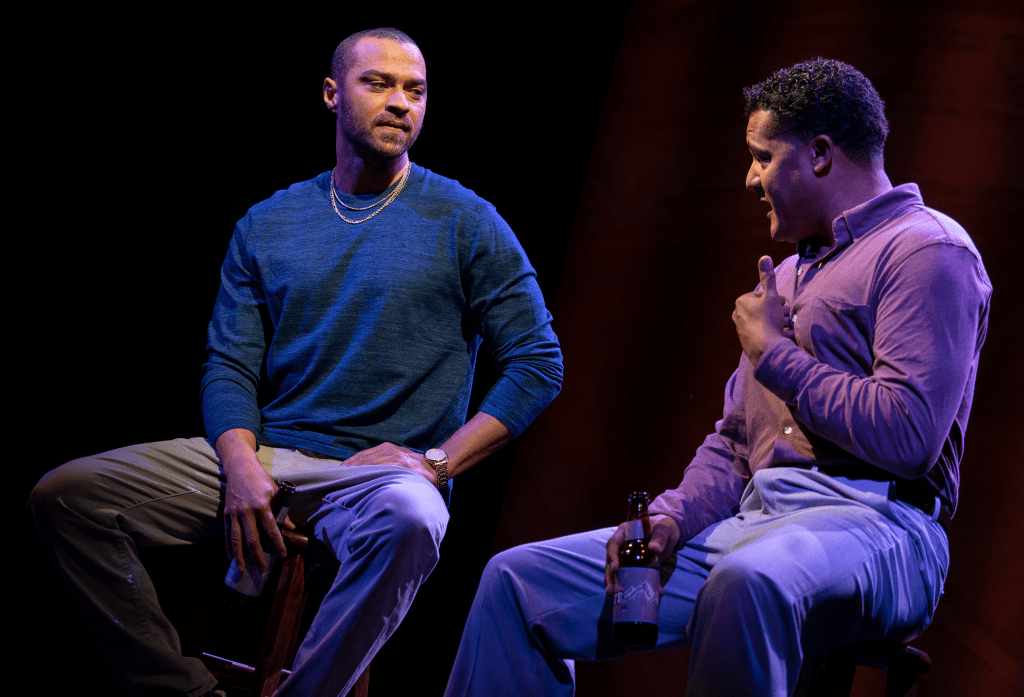

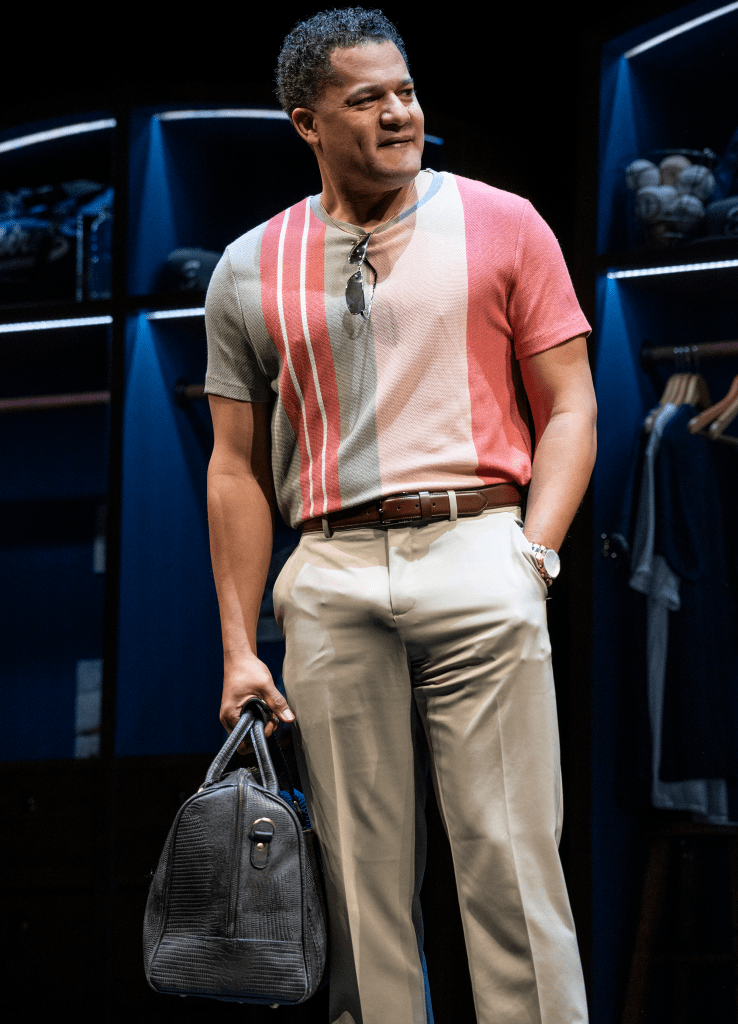

Once again, twenty years later, Take Me Out, the revival for the love of baseball running at 2nd Stage, strikes a pacing home run with bravura performances by Jesse Tyler Ferguson (Mason Marzac), Jesse Williams (Darren Lemming), and Brandon J. Dirden (Davey Battle). Richard Greenberg’s dialogue in the minds, mouths and hearts of the cast never seems more acute, dazzling and dangerous in this “piping time” of Red State/Blue State, as he pumps up the themes of machismo, homophobia, religious bias, gender bias, racism, identity conflicts with color blindness, celebrity privilege, corporate hypocrisy and much more. The second act really takes off, soaring into flight after a perhaps too long-winded first act, whose speeches may have been slimmed a bit to make them even more trenchant and viable.

There is no theme that Greenberg doesn’t touch upon which is current and heartbreaking, except #metoo. That is refreshing because one’s personal rights vs. accountability to the public good are paramount to all spirits inhabiting various bodies whether male, female, transgender, or other. The importance of human rights, human decency and love are crucial in this play because the incapacity of all the characters to embody these qualities remains one of the focal points.

Finally, one does hope that the success of the production will remind all lovers of baseball (the most American of games), that it is the only sport where an active major league player has not come out as gay. As a matter of personal choice and risk, of course, such a decision would be momentous as it becomes for the star of the Empires (think Yankees), Darren Lemming, superbly played by Jesse Williams.

Scott Ellis’ direction is spare and thematically charged. Importantly, “sound” (thanks to Bray Poor, responsible for sound design), heightens the excitement. The emphasis is on the crack of the ball on the bat and the cheering fans. The lighting (Kenneth Posner), is spare. Florescent thin blue lines, representing team colors, square off the space to suggest the players’ emotional confinement. The staging elements rightly place front and center the social dynamic, arc of development and relationships between and among the players.

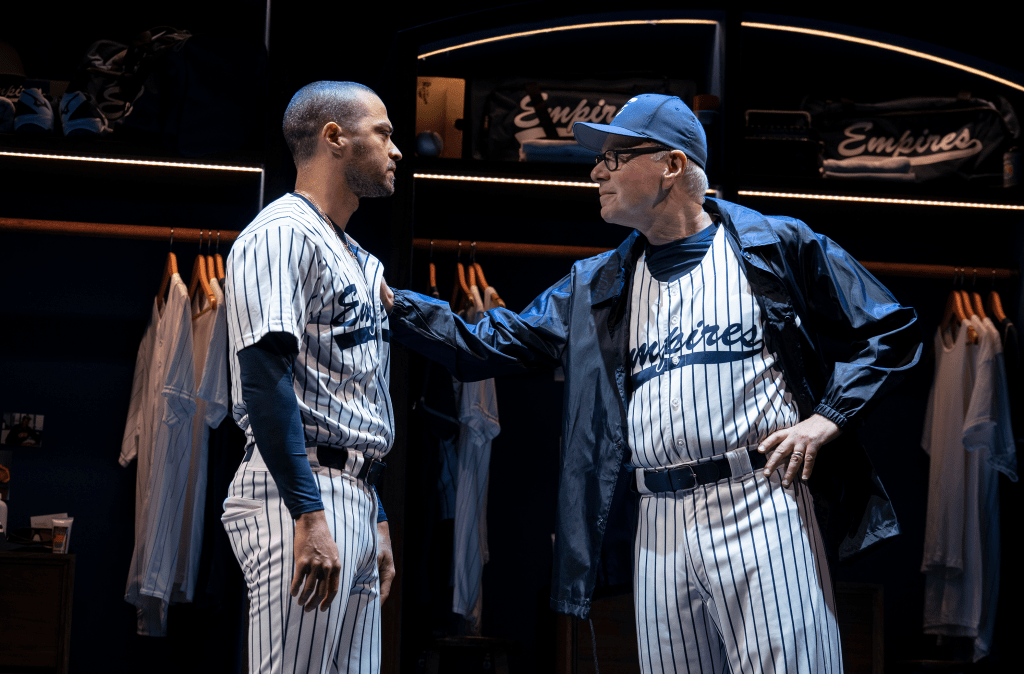

Initially, team camaraderie is thrown into disarray by Darren Lemming, who drips gold from his pores and walks upright in perfection but admits to being gay. His proclamation sends ripples of “shock and awe” through his envious teammates, who worship Lemming’s “divinity,” his steely cool demeanor and very, very fat salary,

We find his teammates response to be humorous. In order not to appear femme they restrict all their male “locker-room” behaviors because they don’t want to “entice” Darren into thinking they are his sexual “kin.” Only Kippy, his self-appointed buddy and narrator who tells part of the story (the fine Patrick J. Adams), chides him for not alerting anyone before his press announcement. Afterward, Kippy humorously teases his friend that the team lionizes who he is and would love to “be him” or “be with him,” on the down low, except that he is now very public. And that would make them very public. So they must keep their distance. Darren is annoyed at this new leprosy which he never experienced or thought he would experience because he is who he is, the team’s greatest.

Meanwhile, Darren’s announcement has forced all to confront where they stand with their own sexuality and sensitive male identity, which Kippy suggests reveals latent gay repression, and Darren suggests is the opposite. From the initial conflict, the Empires go through a roller-coaster of events and emotions that Darren didn’t foresee when he blithely walked between the raindrops and dropped the bomb on his team and Major League Baseball, assuming that because he could handle it, they should handle it.

When it comes to his devoutly traditional Christian friend Davey Battle (the always excellent Brandon J. Dirden), Darren has a blind spot. Instead of quietly discussing his sexual orientation with Davey, a misunderstanding ensues when Davey encourages him to be himself and be unafraid.

Where certain Christians are concerned, being gay is another feature of Christ’s love. Darren assumes that especially with his devout Christian friend, Christ’s love means acceptance. Greenberg holds back the mystery of Davey’s and Darren’s conversation about his being gay, revealing its importance at the end of Act II, when the stakes are at an explosive level. When we discover the identity of the individual who overhears their conversation is a witness to “the event,” we are surprised at the superb twist. Immediately, we understand the conversation happened. There is no way the “overhearing witness” would be lying. It is this conversation that becomes the linchpin of uncertainty, a tripwire to set off questions with no easy answers. There is no spoiler alert. You’ll just have to see this wonderful production to find out the importance of the witness to the conversation.

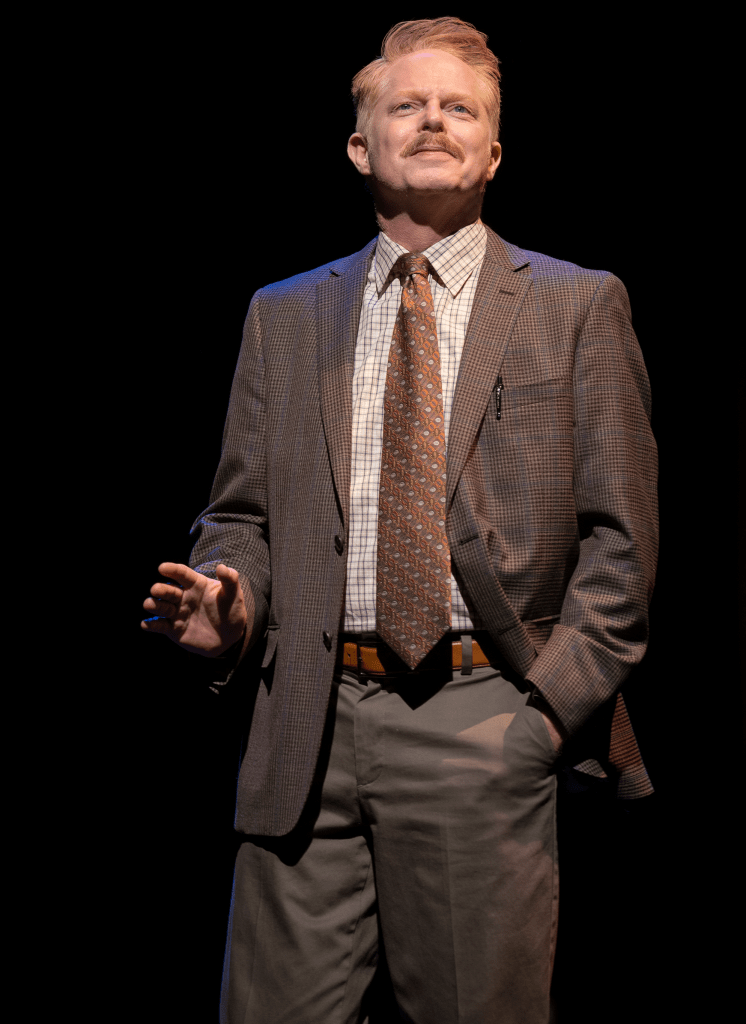

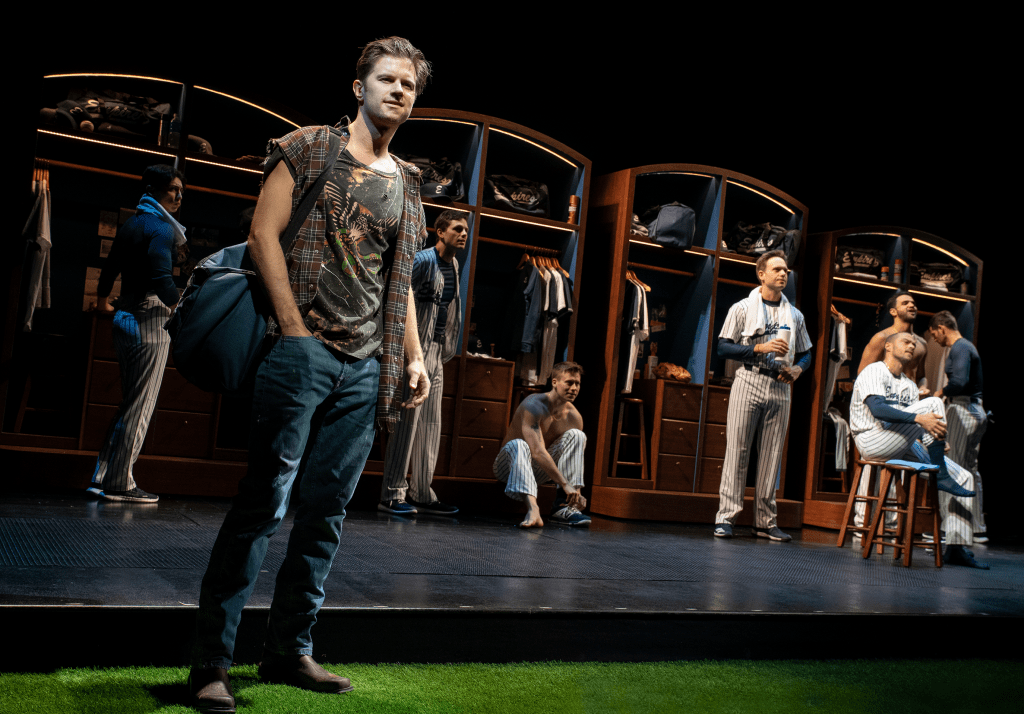

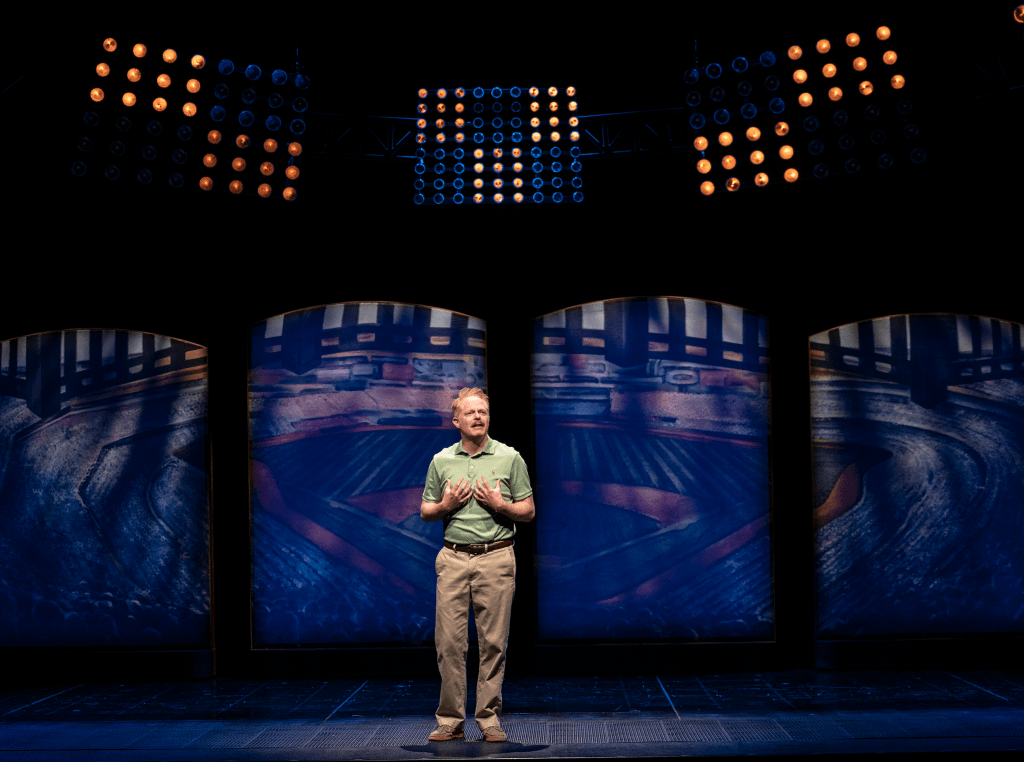

Greenberg covers all his bases with runners in this take down and resurrection of America’s “favorite past-time.” There is personal locker room talk where nude teammates “let it all hang out,” as they shower and face-off against each other, responding to Darren’s announcement and humanizing him because of it. Greenberg’s wit and shimmering edginess work best, revealing his spry characterizations in the banter between Kippy and Darren, and in the growing friendship between Darren and his new financial advisor Mason Marzac, the superbly heartfelt and riotous Jesse Tyler Ferguson. As the consummate outsider who becomes a fan, the character of Mason has the most interesting perspective on baseball, the gay community and the events that happen in real time that result in an unresolved tragedy.

Marzac, meets with cool, collected Darren after the celebrity star outs himself. Ferguson’s Marzac is humorously over the moon about Darren’s courage, his performance and the game. Darren states coming out was not “brave,” unless one thinks something bad will happen, because “God is in baseball,” and Darren is in baseball. And “nothing bad happens to Darren.” This Icarus is flying high. He takes advantage, surreptitiously, smoothly crowing about his stature which outshines his teammates and especially the awe-struck dweeby, unathletic, unbuff Mason.

Of course, the conversation carries tremendous irony in hindsight, because like Icarus who gets burned and crashes to the earth, so does Darren. How Greenberg fashions this is surprising and ingenious. Interestingly, not only does Darren take the team with him emotionally and psychically, they are rewarded despite their corrupt Machiavellian machinations to achieve a win. The irony is heavenly. It is Greenberg’s device, savvy and sardonic, which speaks to theme. Sometimes when you win, it’s not a win if your heart breaks and there are no friends or teammates you can share it with because of emotional separation and alienation. So for the team and especially Kippy and Darren, the win becomes a grave loss that no one can ever appreciate, except baseball idolator, Mason.

But I get ahead of myself praising Greenberg’s irony.

As they discuss Darren’s financial picture, Darren clues Ferguson’s Mason in to the finer points of baseball appreciation, for example to keep “watching” the number coincidences. There’s “a lot of that,” Darren implies as Mason rattles off wondrously, “…the guy who hit sixty-one home runs, to tie the guy who hits sixty-one home runs, in nineteen sixty-one, on his father’s sixty-first birthday.” Mason is ignited by speaking to the amazing and surprisingly gay Darren.

Ferguson shines in his Mason portrayal, as he excitedly waxes over the Americanisms of the game, as pure egalitarian democracy. He emphasizes that everyone has a chance when they get up to bat. But then he states that baseball is more mature than democracy. This comment coupled with the arc of development is an incredible irony considering the team takes in a crackerjack pitcher, Shane Mungitt, who is one of the more florid Red Necks to ever appear on stage. Michael Oberholtzer’s Shane is breathtaking, a stellar, in-the-moment portrayal of a bigot you can actually feel sorry for.

Ferguson’s superbly rendered soliloquy about baseball opens a window into Mason’s kind, perceptive and loving nature. He effusively and humorously describes the requisite home run as a unique moment: the game stops and there is a five minute celebration of cheering time for the fans and the hitter, who rounds the bases like a king, though the ball has long spiraled out of the stadium into the universe. From watching the completely unnecessary round of the bases, Mason says, “I like to believe that something about being human is good. And what’s best about ourselves is manifested about our desire to show respect for one another. For what we can be.”

This is the crux of the play because after this eloquent and high-minded speech, everything falls apart. The winning streak of the Empires, the team relationships, the friendships between Davey and Darren, and between Darren and Kippy implode. And sadly, the once silent, “mind my own business” Shane unravels into a hellish state, careening into the other players with a vengeance that he may not be responsible for, given his upbringing. Thus, not even a winning season saves them from the inner reckoning they have brought upon themselves. If this is America’s favorite past time, it would be better to go back to reading.

Greenberg gives his play’s coda to Mason, who has “evolved” into a baseball aficionado. As such he is brimful of hope, yet ironically perceptive. A tragedy has occurred. However, for him the greater tragedy is that he has to wait a whole half year for the season to begin again. Baseball is that tiny thing that takes one out of the misery of life and makes it worth living, even with its tragedies. In Take Me Out, that is true for the fans. For the players, what occurs is an entirely different and terrible consequence.

Kudos to Scott Ellis’ direction and his shepherding of cast and the creative team. These include Linda Cho (costume design), David Rockwell (scenic design), and others already mentioned. Scott Ellis and the cast have delivered a profoundly humorous and vital, resonant work about a game played throughout our country, revealing that no one, regardless of how we prize sports figures, is worthy of the greatness of the game itself.

For tickets and times go to the website: https://2st.com/shows/take-me-out?gclid=Cj0KCQjwjN-SBhCkARIsACsrBz798inP5l5pUV7hZGFHOj0rWRI1spG27oalp8HyLfnArPnBlPauavsaAkcwEALw_wcB

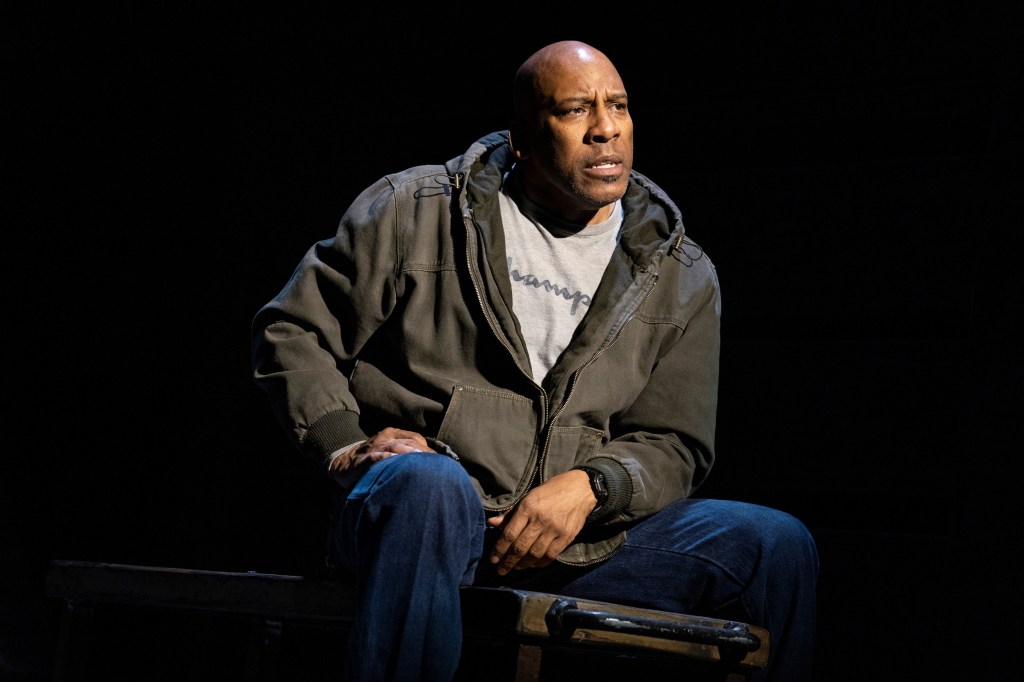

‘Coal Country’ is Amazing

When money and wealth become more important than the lives of others, that is the time to write a play with powerful, sonorous music. Oh, not to uplift the CEOs who collect the millions like Don Blankenship of Massey owned Performance Coal Company. No. The play should uplift and memorialize the ones who die because of that CEO’s greed, selfishness and refusal to accept accountability for what many have called murder. Above all the play must repudiate the wealthCy’s Puritan assertions that money and power make right. They don’t. Not now, not ever.

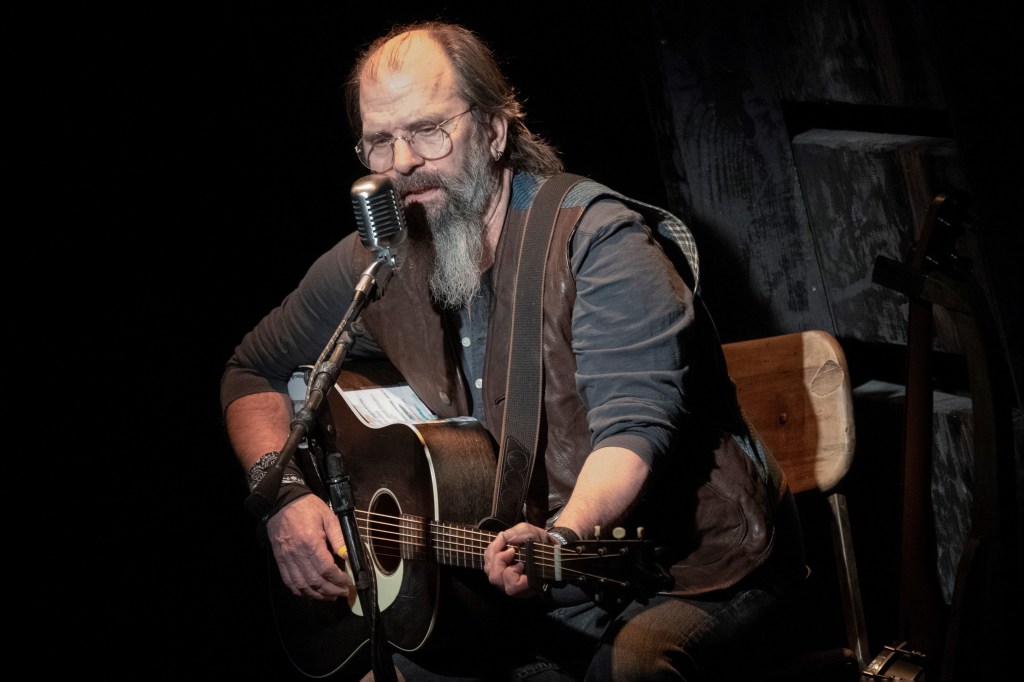

Coal Country is a docu-drama with incredibly relevant themes for us today. The riveting, masterful work written by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen with original music by Steve Earle in a fabulous encore presentation by Audible and the Public Theater seems more impactful each time it is presented. We can never get enough of this exceptionally performed, shining work which runs at the Cherry Lane Theatre until 17 of April.

Though the worst of human nature asserts its primacy, poignant, moving stories like those in Coal Country are timeless in revealing that love despite tragedy culturally work us toward enlightenment. The voices of those who have been wrongfully snuffed out can resonate with meaning. This is especially so when fine artists like Blank, Jensen, Earle and superb performers effect those voices to channel the great moral imperative. What is good, what is true, what is valuable is never lost. It lives on.

The themes which the playwrights and songwriter ring out in Coal Country focus on the devastating catastrophe known as the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster of 2010, which cost 29 West Virginians their lives. Through family eye-witness accounts cobbled together in a tapestry of poetic beauty, vitality and grace, we learn the facts about the huge machine that operated over- capacity 24/7 on the long wall, sheering off the finest, most valuable coal so Blakenship could get his contract percentage of the mine’s earnings of $650,000 a day.

We learn through the accounts of union miners like Tommy (Michael Laurence), Gary (Thomas Kopache), and “Goose” (Joe Jung), how and why government inspectors never found the broken systems that allowed low oxygen levels to increase the build-up of methane gases and thick coal dust that caused the massive explosion. As the experienced miners relate how the broken sprinklers ineffectively doused the sparks created in machine operations that ignited the coal dust and methane behind the long wall, the final picture of egregious negligence and rapacious lust for money clarifies in the blood of innocents merged with the blood of family bonds.

Tommy, Laurence and Gary discuss how the power of the union to protect and respect the miners’ rights in the past has been subverted by the CEO and company, and government de-regulation. The owners who bought the mine hired a large percentage of non-union men, who didn’t dare “speak up,” to government inspectors and the FBI about extremely unsafe conditions in the mine. They feared reprisals. The question of payoffs arises and dead ends. We learn how those miners who did “say something” were warned and ignored. Miners were rendered voiceless against the inevitability of their deaths, because Blankenship was on a mission. No one was going to stop him.

As families identify bodies on blankets on the gravel, some collapse. Roosevelt (Ezra Knight) who identifies his father, who appears to be “asleep,” remains calm until his mother comes. They weep together. As others express outrage, the families of four missing men wait to hear whether or not their loved ones cheated death. Finally, the wait is over. None make it out. Tommy, who loses his son, his nephew and his father, waits to spill the news, overcome with pain.

Judy (Deidre Madigan), a doctor who lost her brother in the catastrophe rides a roller coaster of emotional expectation. First, she believes her brother died. Then she believes he found refuge. Then, all is finality. She describes that she feels she is an outsider because of her socioeconomic status. But emotion and love transcend economics; she is one of them. Her brother is dead and though the medical examiner tells her not to, she insists on seeing his remains. It is ironic that even her medical background does not prepare her for what the mine did to him. It is beyond calculation. In pieces, her brother is without human form.

One by one seven family members tell their story of a simple, satisfying life before the catastrophe in a community that mined for generations. Indeed, the mountain supported and nurtured them until it was bought over by Massey Energy and a new CEO came to town. We learn of the loving relationships between Mindi (Amelia Campbell) and Goose, and Patti (Mary Bacon) and Big Greg who dies leaving Little Greg traumatized by the loss of his dad and Patti when he is taken away from her. And interspersed with their stories, Steve Earle’s country ballads lyrical and poignant drive home the resonance of their love and remembrances of their dear ones. They live in his songs and echo in the actors’ mesmerizing performances.

Blank and Jensen (the husband-wife team who created The Exonerated), choose to present this dynamic piece as a flashback after Earle (playing guitar), opens with two songs that set the themes: “John Henry,” and Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” Cleverly, the action begins in the courtroom at the end of Don Blakenship’s trial as Judge Berger (Kym Gomes), states they cannot read their “Victim Impact Statements.” What family could never speak in court, they relate to the court of public opinion (the audience who sees this play).

The flashback comes full circle back to the court, so the audience hears Blankenship only gets one year in jail and a fine of $250,000. Arrogantly, Blankenship uses that money to run Ads and create pamphlets in which he characterizes himself as the victim of government as a “political prisoner.” Nevertheless, in final, moving encomiums, each family member details how they remember their loved ones who live on in their hearts and in this production which has called. out to music the names of all who died in the UBB mine explosion.

With minimalist but trenchant symbolic Scenic Design (Richard Hoover), effective Lighting Design (David Lander), Sound Design (Darron L West) and Costume Design (Jessica Jahn), Coal Country is an amazing revival. It is profound and memorable in scope and power. Don’t miss it this time around. For tickets and times go to their website: https://www.cherrylanetheatre.org/coal-country

The ‘Plaza Suite’ Snark is Disingenuous #metoo

In his snarky review of Neil Simon’s Plaza Suite, the New York Times’ critic’s “clever,” oh so “entertaining” disposal of the John Benjamin Hickey production into the garbage bin of hideous fustiness seems misguided. To the critic’s dunning I shout, “Au contraire!” The production starring Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker offers a unique, glimmering reflection of the past. It is a past that we need to be reminded of. If one peers into that reflection, and considers the interactions of the characters, one sees how intelligent females bested their male counterparts with surreptitious abandon, superior wit, and brilliant irony. If one’s view is dim and dark, like the NYT critic, one sees little.

From my humble female perspective, one also considers via this production, that between then and now, with all of the hell raising and insistence on progress, and change between straight men’s and women’s relationships, nothing much has changed. Don’t believe me? Have you read any good Evangelical books lately? Have you lived in the South for any period of time, recently? All right, maybe that doesn’t make sense to you.

Well, I will remind you about that pesky statistic (one in four women are violently abused by their partners), that has yet to budge off its number. Abusing females is alive and well, and that’s despite #metoo which is a meme that only applies to the celebrated, rich and famous, including well-paid male theater critics. In plebian circles if a woman attempts to speak up, a hand often goes upside her head. And what happens after that is anyone’s guess.

That Simon exults in the superiority and cleverness of each of the female characters in the play is lost on the critic which is understandable as he is not a female. He is a male looking in and once again judging the female characters and finding them and the production fusty, dusty and musty. Unfortunately, he shallowly superimposes his #metoo version of the female perspective on the characters, thus making the push to be politically correct all the more hypocritical and disingenuous. And frankly some of it is nonsensical, though there appears to be “logic” in what he is doing because the piece is well edited. Is his editor a male too?

Ah, forget what I just stated. Be overwhelmed by the “smart attitude” of the New York Times critic who displays his own “genius,” sense of privilege and arrogance via his male writerly superiority, which is nowhere near the genius of say, Gore Vidal (a favorite of mine). So caught up in admiring his style in the mirror, he misses the themes and the currency of Hickey’s vision. He also misses the fact that relationships between men and women have gone nowhere because human misunderstanding and fear and inability to confront death and lies by keeping them at bay through self- manipulation is an everpresent fact encompassing the relationships, in Plaza Suite.

But none of that was picked up by the critic to whom the 1960s was such a thing of the past, it doesn’t exist in his imagination; nor does he appear to want to be reminded of it, if it did exist.

Instead, what is of great importance to him, it would seem, is bowing to politically correct memes. Tragically, that is a blindness and acute hypocrisy. Currently, I boycott the New York Times. I am tired of the same pap from this particular NYT critic whose dullness would be raw meat for Noel Coward, if he were alive. I stumbled upon the review clued in by a studio professor, and well-produced playwright who mentioned the tenor of the review because he knows such pablum makes me livid.

The privilege he displays is a long-held tradition at the New York Times. Females, largely absent in theater as critics, directors, etc., commented upon by Director Rachel Chauvin in her acceptance speech for Hadestown is an example of how #mettoo doesn’t work in the theater world. Perhaps the reason is that female critics and reviewers are not #metoo politically correct enough. Perhaps females don’t remind us enough that various productions are not “politically correct.” Shall I discuss LGBTQ?

Truly. Perhaps for future productions directors and producers should wipe out the canon of plays written before 2017 and #metoo, etc., as worthless. What could possibly be learned from them?

Indeed, if critics are to genuinely benefit audiences who see plays, then they must perceive, think and above all go deep. First, understand what the director’s vision is. Is the director presenting that which on first assumption perhaps the critic didn’t get? Does it pass the audience test?

The night I saw the production, Plaza Suite did pass the audience test. They enjoyed it. Thus, I agree to disagree with the NYT and the Wall Street Journal critics. The below review, which also appeared in Sandi Durell’s Theater Pizzaz explains why.

My Review of Plaza Suite: A Female Perspective

Judging by the applause as the curtain lifts and John Lee Beatty’s luxurious, shimmering set for Plaza Suite unveils, director John Benjamin Hickey’s glorious throwback to the gilded Broadway of “yesteryear,” intimates a night of enjoyment. Coupled with its second harbinger of success, enthusiastic cheers at the entrances of the husband-and-wife team Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick, the Neil Simon revival emblazons itself a smash even before Karen (Parker) and Sam (Broderick) have their first disagreement.

Not one moment falters in the pacing or mounting crescendo of hilarity in this superbly configured production about a suite of rooms (a conceit knock-off of Noel Coward’s Suite in Three Keys). There, visitors from Mamaroneck, Hollywood and Forest Hills play out their dreams and face their foibles in room 719 at the historic Plaza Hotel. That the place is still standing is a source of Simon witticisms.

Apparently, rumors of its being bought over by rapacious developers to be torn down making way for state-of-the-art buildings even existed at Simon’s writing. The theme of the ugly new replacing the beautiful old and historic as a pounding mantra of New York City is everpresent and a sometime theme in the triptych of playlets about couples.

Hickey shepherds Parker’s and Broderick’s performances, delivered with “effortless” aplomb, gyrating from one comedic flourish to another to the amazing farcical finale. Authentically and specifically (gestures, mannerisms, presence, posture), they hone the characterizations of three disparate couples, breathing into them the humanity we’ve all come to love and loathe. We didn’t want the fun to end, and it was apparent that neither did they.

The few times they broke each other up or comfortably ad libbed, they let the audience in on the endearing fact that they were having a blast. That mutuality between audience and performers was doubly so because they’ve been waiting to perform for two years of COVID hell. Happy to be back in front of a live audience, their enthusiasm was communicated by the ineffable electricity that happens in live performance and changes nightly because of the audience’s diverse sensibilities. The performers vibrated. The audience vibrated back. The circle completed and rolled around for the next laugh which topped the next.

Ingeniously entertaining, incredibly performed, Plaza Suite at the Hudson Theatre which runs for a limited engagement is a spectacular winner. Here’s why you should see it.

Though Neil Simon’s concept that he lifted from Coward has been reshaped and used by playwrights and screenwriters since the 1960s when Simon wrote Plaza Suite, the production gives it a unique uplift because of its specificity and attention to detail. Importantly, viewed through a historical lens, the relationships, character intentions and conflicts ring with comical verities. Wisely, Hickey allows the characters inhabited by these sterling performers to chronicle the values and folkways of the sixties which were a turning point in our society and culture. The understanding that arises from Simon’s exploration suggests why we are where we are today.

Finally, using humor the play deeply touches on seminal and timeless human topics: fear of aging, seduction, loneliness, marriage unsustainability, the generation gap and more.

In the first playlet, Karen’s Mamoneck housewife chafes in a relationship which she unconsciously senses has soured. She books Suite 719 to celebrate her anniversary with Sam and ironically initiates the reverse.

Listening carefully and watching Parker’s Karen, noting her plain outfit and hairstyle and comparing it to Broderick’s Sam, the laconic, dapper, sharp, appearance obsessed businessman, we should anticipate what will happen. We don’t because Simon’s keen, witty dialogue of thrust and parry between Sam and Karen keeps us laughing and because the performances are so spot-on, in the moment, we, like the characters, don’t know what’s happening next. However, of course, Broderick and Parker do. Yet, they are so alive onstage, that the characters’ reactions remain a surprise and the revelations are unanticipated.

Karen’s ironic subtext brilliantly digging at Sam to confess he’s having an affair is wonderful dialogue expertly delivered. A few of Parker’s lines bring down the house with her sharply paced delivery. One is her crackerjack response to Sam’s “What are we going to do.” Without a blink Parker’s “You’re taken care of. I’m the one who needs an activity,” receives audience whoops and hollers. An age-old event of cheating and adultery is born anew.

Simon’s snapping-turtle dialogue in the face of today’s hackneyed insult humor is wickedly scintillating. In the Hollywood seduction playlet, High School sweethearts become reacquainted. Broderick’s smarmy Hollywood producer Jesse Kiplinger decked out in his Mod finest is a classless nerd who confesses his unhappiness with the Hollywood slime set and his three *&$% ex-wives who take not only his money but his guts and soul. Muriel in Parker’s equivalent of her fashionable self in the ‘60s, is enthralled by Jesse’s Hollywood persona, but is in keeping with the innocent, demure women Jesse remembers. The hilarity builds into what becomes a reverse seduction scene by a steaming married woman when they “get down to brass tacks.”

All stops are pulled in “A Visitor from Forest Hills.” The costumes (Jane Greenwood), the hair and wig design (Tom Watson), contribute to building the maximum LMAO riot. The inherent action and zany organic characterizations by Broderick and Parker augment to hysteria when Mimsey refuses to attend her own wedding and ensconces herself in the bathroom.

Norma and Roy implore Mimsey attempting to psychologically manipulate her and each other to get her to come out. Parker and Broderick effectively create the image of their daughter crying, possibly suicidal, as she remains unseen, silent and incorrigible behind the sturdy, unbreakable bathroom door. Desperate to stem a disastrous day, Broderick’s “out of his mind with frustration” Roy even goes out on the ledge and braves a pigeon attack and thunderstorm to wrangle in his wayward child. Broderick’s mien and gestures bring on belly laughs.

What they do to move heaven and earth to get Mimsey to come out is priceless comedy that is easier than it looks. The frustration and fury the actors convey with the proper balance to appear realistic yet crazy and smack-me funny is what makes this over-the-top segment fabulous.

Kudos to the artistic team which includes Brian MacDevitt (lighting design) and Scott Lehrer (sound design). For tickets go to https://plazasuitebroadway.com/

‘English’ a Seminal Play by Sanaz Toossi

Born into our parents’ culture and country, we learn how to communicate with them easily and take our language for granted without thinking about it. Delving deeper, language defines us, defines our thoughts, our ways. Our name in our native language has meaning from its history. It describes who we are and how we perceive ourselves. Many change their names as a result, knowing the change means a different self. Considering the import of the language we speak and our identification with it, how does learning a new language impact the way we understand ourselves? How might learning another language affect our being?

English, the insightful and powerful work by Sanaz Toossi, presents these questions and answers them poignantly through the voices of five individuals from Iran, who grapple with learning English. Starring an all-Iranian cast, the play enjoyed an extended run at The Atlantic Theater Company and most probably will be a favorite to be staged globally. Directed by Knud Adams, the play remains an original that unfortunately, couldn’t have had a longer run.

The setting is Karaj, Iran in 2008 before and during a confluence of events taking place between Iran, the United States and other English speaking countries. At the time immigration is fairly easy and Iranians on the move want to study abroad, do business and travel for extended stays to English-speaking countries to which their families emigrated.

Marjan (Marjan Neshat portrays the instructor), teaches for the TOEFL, the Test of English as a Foreign Language. The standardized, timed test measures the English language ability of non-native speakers, who wish to study in English-speaking universities. The test is accepted by more than 11,000 universities and other institutions in over 190 countries. The selective test guarantees that the students have an excellent working knowledge of the language to insure their success, not only in their classes, but also in navigating the culture and society.

As Neshat’s Marjan teaches, she realizes as we do that in every class there is a dynamic. Personalities emerge. Though she attempts to be objective, she finds herself aligning with students who demonstrate like-minded abilities and cognition. As her students reveal themselves in their response to her and the language, we find their observations humorous, their interactions fascinating. And the conflict arises when the struggling and often embarrassed students relate her to the onerous time they have with learning a completely different mode and thought process of communication. Neshat is authentic in her portrayal as Marjan, revealing the inner emotional struggle she has especially with Elham (the feisty, assertive Tala Ashe).

Humor evolves organically from the students’ perceptions, struggles and slippage into their native tongue Farsi in the first weeks of the class. An excellent teacher, Marjan attempts to gradually curb their fear and angst holding their feet to the fire by speaking only English and giving them a demerit if they fall back into Farsi. Her skills are effective. We watch these individuals speak halting English. When they rip off sentences quickly (in English), that designates they speak Farsi.

At the outset Neshat’s Marjan reveals equanimity despite the competitive confrontations of Elham (the excellent Tala Ashe), the shy, halting behavior of Goli (the sweet Ava Lalezarzadeh), and the lackluster, removed Roya (the heartfelt Pooya Mohseni). Eventually, it becomes apparent that Omid (the attractive, confident Hadi Tabbal), the only male in the class, whose English is nearly unaccented and spot-on, is the one that Marjan connects with cognitively and perhaps, as Elham suggests, on a more personal level. Neshat and Tabbal effect an intriguing bond that flows with undercurrents between their characters.

We enjoy Marjan’s activities with the class which reinforce recognition of English nouns through games that emphasize speed. She keeps in mind the TOEFL is a timed test. However, eventually, the language begins to wear down the teacher and the students after Neshat’s Marjan encourages them to undertake the most difficult part of learning a language; they must only speak in English.

Thus, they must converse in sentences, and in effect begin to approach thinking as a native English speaker. All of them chafe at this and break into Farsi which Neshat’s Marjan “censures” by noting it on the chalkboard. The only one who doesn’t find this difficult is Tabbal’s Omid.

As Marjan attempts to have each of the students integrate themselves more personally with English, the conflicts explode. We discover Mohseni’s Roya only wants to learn because her son wants his mother to speak to her Canadian granddaughter in her native tongue which is not Farsi. This devastates Roya, who in a show and tell explains the two languages as she hears their differences. When she discusses her son’s email in Farsi and a voice mail he leaves in English, she uplifts the beauty of Farsi. She emphasizes the softness of her son’s intent in Farsi. Then she notes in his English voice mail, his speech. The sounds he makes are harsh, removed, cold. She asks the class, “Who is mom? I am Maman.” There, in one word the history of Persia is eradicated. The audience was completely silent during Mohseni’s plaintive discussion of loss; her son and granddaughter disappearing her culture before her eyes. This powerful moment is beautifully rendered by Mohseni and insightfully directed by Knud Adams.

The distinction Toossi suggests is profound and thought-provoking. Roya’s relationship to her son has been separated by the nature of the language, and we see her heart is broken because of it. As he lives in Canada over the years, the separation will become impossible. The geographical difference matters little. It is his adoption of this new way of being in English. Even if she stays with him in Canada, she will be forced to learn this harsh, cold speech and ways of thinking to attempt to form a relationship with her granddaughter. But a culture, a way of being, a way of life and history has been disintegrated in the next generation. Mohseni’s Roya defines this as a death. As a result of her incredible performance, we believe and buy into Roya’s grief. Her granddaughter will never know the softness and poetic beauty of Farsi, the language of poets, of Omar Khayyam.

When Marjan has all of her students speak their English names, Roya rebels. It is her last stand. She never returns to class. We anticipate that the cost is too great for her to be reborn into a culture that reshapes her identity with an ugly name and being. As Roya leaves the class, Marjan’s response is invisible, absent. When a student asks what happened to Roya, Marjan dismisses the question. We are left to think that Roya failed to even desire to evolve, and Marjan failed Roya. Marjan, normally empathetic, moves on to “save” the others. However, Neshat’s Marjan too swiftly dismisses Roya. The undercurrent of her own feelings screams out with her silent dismissal, as harsh as the sounds of English to Roya’s intellect.

Toossi makes an important choice for our understanding of the complicated Marjan who puzzles us. Why didn’t she use Roya’s difficulty as a teachable moment? Why didn’t she encourage the others or explore for a few minutes a path to enhance their connection with her? We don’t know if she deeply empathizes and understands Roya’s rebellion or if she is annoyed she failed her. The question Toosi raises about Marjan’s character, she never answers because it is a developing characterization steeped in a confluence of emotions and feelings. Clearly Neshat’s Marjan is thrown by this event. Her becoming an English teacher has impacted her. There is gain, and there is loss and there is the price she pays for the trade-off.

Pooya Mohseni’s portrait of Roya is eloquently delivered, touching and emotionally driven. In every line we feel Roya’s pain in having to deal with this untenable situation. Mohseni knocks it out of the ballpark. Through her character most of all, we understand what it means to be a native speaker. We empathize with the loss of dignity, honor and person-hood Roya feels being forced into speaking English by Neshat’s Marjan. We get how Marjan’s restrictions not to communicate and make herself understood in the beauty of Farsi is anathema. Of course, she feels English is like putting on a cloak of stupidity, ugliness, ungainliness. If her granddaughter never learns Farsi (something Omid suggests her son should have his daughter do), she will never know who her grandmother really is. Roya’s loss, historical, cultural, personal is beyond calculation.

Toossi’s strongest moments present themes of loss of the old identity, yet the incomplete adoption in fluid grace with a new one. For each of the characters, we empathize that it is like being birthed again, torn from one’s natural lush habitat and plopped down in a desert left to die of thirst every moment, as they yearn to feel the cool balm of speaking in one’s mother tongue. English shines when the pronounced conflicts increase.

For example, Elham’s ambitious nature and brilliance force her to try to be the best in the class to achieve a high grade on the TOEFL in her pursuit to be a doctor. Ashe nails Elham’s frustration in achieving a high score on the MCAT and fearing a low score on the TOEFL. The TOEFL is a mountainous hurdle, so she hates English and by extension is oppressed by Neshat’s Marjan. Nevertheless, her competitive nature compels Elham to provoke Marjan in the stress and strain of being challenged. Speaking Farsi, yearning to be close, she manipulatively accuses Marjan of disliking her.

Ashe’s exceptional portrayal is revealed in her character’s suppressed anger. Thus, Elham proclaims to Ava Lalezarzadeh’s Goli that Marjan “loves” Omid. The sweet, shy Goli avers. But Elham insisits that because Marjan invites Omid to watch English films with her there is a “bond.” Indeed, in their moments together Tabbal’s attractive Omid is suggestive and in his scenes with Neshat’s Marjan there is a connection. However, it is not as Ashe suggests; it is based in understanding English fluidly. Indeed, Marjan invites Elham and Goli, but they don’t want to spend the time with Marjan and Omid watching films like Room With a View. These conflicts are vital to the play’s forward movement. Perhaps they might have been established earlier.

Toossi’s uses her characterizations to organically develop her themes. These strengthen our engagement and pull at our empathetic heart strings. Thus, when Omid’s mystery is revealed or when Elham comes back to discuss how she performed on the TOEFL, we identify. Most of all Toossi has accomplished a milestone by indicating the importance for native speakers to stand in the shoes of immigrants who are even attempting to learn English. To learn a different language is a courageous, heroic feat, as Toossi suggests. It is a willingness to expand to another identity, another thought process. Ultimately, the nature of the language, its formation and structure changes the individual emotionally, mentally, indeed psychologically. This must not be underestimated. All of the actors’ portrayals vitally heighten Toossi’s themes and bring us closer to the importance of empathy. Ashe’s development of her character Elham is exceptional and we thrill for Elham as she shocks us with her success which was in her all along.

Toossi also reveals why there are those who don’t wish to learn English, even though they’ve lived in an English speaking country for years. These individuals remain in their own communities, never learn the language and never venture out to immerse themselves in new experiences. The risk of embarrassment is too great. They will not live in humiliation as their new persona, feel like an idiot and be quiet and uncommunicative, not understanding the too rapid speech bursts around them.

Finally, Toossi implies that by leaving behind the old self and adopting a new one, the individual wipes out the favored history of their beloved country, identity, relationships, being. Of course, if there is no direct imperative for business or education, they will not even try. Additionally, in the United States, their accent will be so thick it will be tantamount to a “war crime,” especially in the rural South and West as Ashe’s Elham ironically and humorously suggests.

This is one of the great lines in Toossi’s superb play. Understandably, non-native speakers do not wish to brave the looks of disgust, horror and puzzlement on the faces of native English speakers when they try to ask, “When will the waiting room open?” (Ws without an accent are particularly hard for non-native English speakers). Toossi covers a great deal of ground in her touching play which ends on a high note. We finally hear the actors speak in Farsi.

The production has ended. A few points about when I saw it the last day of its extended run.

Some of the actors couldn’t be heard, even by those sitting in the second row. Friends sitting there told me they barely heard certain thin-voiced actors. Also, sitting up close they became annoyed because the chairs blocked their view at times and they had to lean to the left or right. I was in row F and I thought it was just me when I missed some of the dialogue. I wasn’t the only one.

Problematic was the set construction, a lovely box set classroom which kept in the sound and echoed it. A wonderful idea for the set shouldn’t obstruct the audience’s enjoyment of the production with occluded sight lines and muffled sound. The idea of the classroom, revolving on a turntable platform is symbolic. But unless the audience hears each line of the actors and sees all areas of the stage without obstruction, the symbolism is impaired. This is too wonderful a work for it not to be technically spot-on.

Look for the marvelous Toossi’s work. She is a treasure and English is a vibrant, important and current play that begs to be performed again.

‘A Touch of the Poet’ The Irish Rep’s Brilliant Revival Exceeds Its Wonderful Online Performance. Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Poet’ is Amazing Glorious Theater!

From the moment Cornelius “Con” Melody (Robert Cuccioli) appears, shaking as he holds onto the stair railing of the beautifully wrought set by Charlie Corcoran, we are riveted. Indeed, we stay mesmerized throughout to the explosive conclusion of the Irish Repertory Theatre’s A Touch of the Poet by Eugene O’Neill. Compelled by Cuccioli’s smashing performance of Con, we are invested in this blowhard’s presentiments, pretenses and self-betrayal, as he unconsciously wars against his Irish heritage. Con is an iconic representative of the human condition in conflict between soul delusion and soul truth.

What will Con’s self-hatred render and will he take down wife Nora and daughter Sara (the inimitable pairing of Kate Forbes and Belle Aykroyd), in his great, internal classicist struggle? Will Con finally acknowledge and accept the beauty and enjoyment of being an Irishman with freedom and hope? Or will he continue to move toward insanity, encased in the sarcophagus image of a proper English gentleman? This is the identity he bravely fashioned as Major Cornelius Melody to destroy any smatch of Irish in himself. O’Neill’s answers in this truly great production of Poet are unequivocal, yet intriguing.

The conflict manifests in the repercussions of the drinking Con takes on with relish. So as Cuccioli’s Con attempts to gain his composure and stiffly make it over to a table in the dining room of the shabby inn he owns, the morning after a night of carousing, we recognize that this is the wreck of a man physically, emotionally, psychically. His shaking frame soothed by drink, which wife Nora (Kate Forbes), brings to him in servile slavishness, is the only companion he wants, for in its necessity as the weapon of destruction, it hastens Con’s demise. The beloved drink stirs up his bluster and former stature of greatness that he has lost forever as a failed Englishman and even bigger failure as comfortable landed gentry in 1828 Yankee country near Boston.

Director Ciarán O’Reilly and the cast heighten our full attention toward Con’s conflict with the romantic ideal of himself and the present reality that will eventually drive him to a mental asylum or a hellish reconciliation with truth. All of the character interactions drive toward this apotheosis. The actors are tuned beautifully in their portrayals to magnify the vitality of this revelation.

Nora (Forbes is authentic and likeable), is the handmaiden to Con’s process of dissolution. In order to fulfill her own glorified self-reflection and identity in loving this once admirable gentleman, she coddles him. Riding on the coattails of her exalted image of Con, she maintains beauty in her self-love. She loves him in his past glory, for after all, he chose to be with her. So Nora must abide in his every word and deed to maintain her loyal happiness, taking whatever few, kind crumbs he leaves for her under the table of their marriage. As a result, she would never chide or browbeat Con to quit the poison that is killing him.

The good whiskey he proudly provides for himself and friends like Jamie Cregan (the excellent Andy Murray), to help maintain the proper stature of a gentleman, steadies his mind. The whiskey also makes him feel in control of his schizoid personas. He clearly is not in control and never will be, unless he undergoes an exorcism. The audience perversely finds O’Neill’s duality of characterizations in Con and the others amusing if not surprising.

Cuccoli’s Con at vital moments rejects the painfully failed present by peering into his mirrored reflection to quote Lord Byron in one or the other of two mirrors positioned strategically on the mantel piece and a wall. There, fueled by the alcohol, he re-imagines the glorious military man of the Dragoons as he stokes his pride. Yet, with each digression into the past, he torments his inner soul for reveling in his failed delusion.

Likewise, each insult he lashes against Nora, who guilty agrees with him for being a low Irish woman, both lifts him and harms him. It is the image of the Major ridiculing Nora because of the stink of onions in her hair one moment, and in self-recrimination, apologizing moments after for his abusiveness. In his behavior is his attempt to recall and capture his once courageous, successful British martial identity, while rejecting the Irish humanity and decency in the deep composition of his inner self.

Always that true self comes through as he recognizes his cruelty. He behaves similarly with Sara, bellicose in one breath, apologetic in the next, fearful of her accusatory glance. In this production Con’s struggle, Nora’s love throughout and Sara’s resistance and war with herself and her father is incredibly realized and prodigiously memorable. O’Reilly and the cast have such an understanding of the characters and the arc of their development, it electrified the audience the night I saw it. We didn’t know whether to laugh (the humor originated organically as the character struggles intensified), or cry for the tragedy of it. So we did both.

Con’s self-recrimination and self-hatred is apparent to Nora whose love is miraculously bestowed. His self-loathing is inconsequential to Sara, who torments him with an Irish brogue, lacerating him about his heritage and hers, which the “Major” despises, yet is his salvation, for it grounds him in decency. Sara and Nora are the bane of his existence and likewise they are his redemption. If only he could embrace his heritage which the “scum” friends who populate his bar would appreciate. If only he could destroy the ghost of the man he once was, Major Cornelius Melody, who had a valiant and philandering past, serving under the eventually exalted Duke of Wellington.

Through the discussions of Jamie Cregan with Mick Maloy (James Russell), we learn that the “Major identity” caused Con to be thrown out of the British military and forced him to avoid disgrace by settling in America with Nora and Sara. We see it causes his decline into alcoholism, destroys his resolve and purpose in life, and dissipates him mentally. It is the image of pretension that caused the bad judgment to be swindled by the Yankee liar who sold him the unproductive Inn. Sadly, that image is the force encouraging the insulting, emotional monster that abuses his wife and daughter. And it is a negative example for Sara who treats him as a blowhard, tyrant fool to vengefully ridicule and excoriate about his class chauvinism, preening airs and economic excesses (he keeps a mare to look grand while riding). It is the Major’s persona which brings them to the brink of poverty.

The turning point that pushes Con over the edge comes in the form of a woman he believes he can steal a kiss from, Deborah Hartford, the same woman whose intentions are against Sara and her son Simon Hartford falling in love. Without considering who this visiting woman might be, Con assumes the Major’s pretenses and we see first hand how Con “operates” with the ladies. His romanticism awkwardly emerges, left over from his philandering days with women who fell like dominoes under his charms. He is forward with Hartford who visits to survey the disaster her son Simon has befallen, under the spell of Sara’s charms, behavior not unlike Con’s. The scene is both comical and foreboding. From this point on, the events move with increasing risk to the climactic, fireworks of the ending.

As Deborah Hartford, Mary McCann pulls out all the stops in a performance which is grandly comical and real, with moment to moment specificity and detail. When Con attempts to thrust his kiss upon her, there were gasps from the audience because she is a prim Yankee woman of the upper classes who would find Con’s behavior low class and demeaning. That he “misses” the signs of who she is further proves his bad judgment. Sara is appalled and Nora, not jealous, makes excuses for him satisfying herself. The scene is beautifully handled by the actors with pauses and pacing to maximum effect.

McCann’s interaction with Aykroyd’s Sara is especially ironic. Deborah Hartford’s speech about the Hartford family male ideals of freedom and lazy liberty that forced the Hartford women to embrace their husbands’ notions by taking up the slave trade is hysterical. As she mildly ridicules Simon’s dreams to be a poet and write a book about freedom from oppressive, nullifying social values, she warns Sara against him. It is humorous that Sara doesn’t understand what she implies. Obviously, Deborah Hartford suspects Sara is a gold digger so she is laying tracks to run her own train over any match Sara and her son would attempt to make. After discovering the economically challenged, demeaned Melody family, Hartford informs her husband who sends in his man to settle with the Melodys.

Together McCann and Aykroyd provide the dynamic that sets up the disastrous events to follow. Clearly, Sara is more determined than ever to marry Simon and as the night progresses, she seals their love relationship with Nora’s blessing, until Nora understands that her daughter walks in her own footsteps in the same direction that she went with Con. Unlike Nora, however, Sara is not ashamed of her actions.

O’Neill’s superb play explores Con’s past and its arc to the present, revealing a dissipated character at the end of his rope. Wallowing in the Major’s ghostly image, Con vows to answer Mr. Hartford’s insult of sending Nicholas Gadsby (John C. Vennema looks and acts every inch the part), to buy off Sara’s love for Simon and prevent their marriage. After having his friends throw out the loudly protesting Gadsby, Con and Jamie Cregan go to the Hartfords to uphold the Major’s honor in a duel. Nora waits and fears for him and in a touching scene when Sara and Nora share their intimacies of love, Nora explains that her love brings her self-love and self-affirmation. Sara agrees with her mother over what she has found with Simon. The actors are marvelous in this intimate, revelatory scene.

The last fifteen minutes of the production represent acting highpoints by Cuccioli, Forbes, Aykroyd and Murray. When Con returns alive but beaten and vanquished, we acknowledge the Major’s identity smashed, as Con sardonically laughs at himself, a finality. With the Major’s death comes the hope of a renewal. Finally, Con shows an appreciation of his Irish heritage as he kisses Nora, a redemptive, affirming action.

O’Neill satisfies in this marvelous production. The playwright’s ironic twists and Con’s ultimate affirmation of the foundations of his soul is as uplifting as it is cathartic and beautiful. Nora’s love for Con has finally blossomed with the expiation of the Irishman. It is Sara who must adjust to this new reality to redefine her relationship with her father and reevaluate her expectation of their lives together. The road she has chosen, like her mother’s, is hard and treacherous with only her estimation of love to propel her onward.

From Con’s entrance to the conclusion of Irish Repertory Theatre’s shining revival of Eugene O’Neill’s A Touch of the Poet, presented online during the pandemic and now live in its mesmerizing glory, we commit to these characters’ fall and rise. Ciarán O’Reilly has shepherded the sterling actors to inhabit the characters’ passion with breathtaking moment, made all the more compelling live with audience response and feeling. The production was superbly wrought on film in October of 2020. See my review https://caroleditosti.com/2020/10/30/a-touch-of-the-poet-the-irish-repertory-theatres-superb-revival-of-eugene-oneills-revelation-of-class-in-america/

Now, in its peak form, it is award worthy. Clearly, this O’Neill version is incomparable, and O’Reilly and the actors have exceeded expectations of this play which has been described as not one of O’Neill’s best. However, the production turns that description on its head. If you enjoy O’Neill and especially if you aren’t a fan of this most American and profound of playwrights, you must see the Irish Rep presentation. It is not only accessible, vibrant and engaging, it deftly explores the playwright’s acute themes and conflicts. Indeed, in Poet we see that 1)classism creates personal trauma; 2)disassociation from one’s true identity fosters the incapacity to maintain economic well being. And in one of the themes O’Neill revisits in his all of his works, we recognize the inner soul struggles that manifest in self-recrimination which must be confronted and resolved.

Kudos to the creative team for their superb efforts: Charlie Corcoran (scenic design), Alejo Vietti & Gail Baldoni (costume design), Michael Gottlieb (lighting design), M. Florian Staab (sound design), Ryan Rumery (original music), Brandy Hoang Collier (properties), Robert-Charles Vallance (hair & wig design).

For tickets and times to the Irish Repertory Company’s A Touch of the Poet, go to their website: https://irishrep.org/show/2021-2022-season/a-touch-of-the-poet-3/

‘The Daughter-in-Law,’ by D.H. Lawrence is Superb! Theater Review

D.H. Lawrence is rarely known for his plays. However, British critics have noted that he was a master playwright, and if discovered as such earlier in his life, he would have been appreciated for his dramas, however maverick and forward-thinking. One such incredibly rich play is being presented by the always excellent Mint Theater Company, who enjoys bringing to life rare jewels in drama that have often been overlooked. The Daughter-in-Law is one of these gems.

Directed by Martin Platt The Daughter in Law presents an amazing portrait of an independent woman, Minnie (Amy Blackman), a former governess married to a collier (coal miner), Luther Gascoyne (Tom Coiner). The couple live in a mining town near his mother’s (Mrs.Gascoyne-Sandra Shipley) home where his brother Joe (Ciaran Bowling), also a collier, works with him in East Midlands England.

The setting is autobiographical and akin to where D.H. Lawrence’s father worked and where he and his siblings lived with their mother (reminiscent of Minnie), who had cultural aspirations for Lawrence, and who inspired him in his studies. Lawrence’s play evolves into conflicts among the characters. These are rich in thematic evolution that comes to some resolution by the end of the play after the colliers riot against scab workers during a strike. Interestingly, the themes involve gender roles, class, economic inequity and familial love. Also, Freudian tropes between mothers and sons, an issue that Lawrence often investigated, receives a hearing in this realistic and beautifully acted production that Platt has tautly directed, so it remains provocatively, emotionally, tense throughout.

To a fault, the actors have been schooled in the Midlands accent which provides realism and creates the audiences’ attentive stir to understand all that the characters communicate. At times, this takes getting used to. However, the actors portray the characters’ emotional feeling sincerely and authentically, so that one understands, even though one may not be able to translate word for word what the characters say.

Nevertheless, when Joe (the vibrant Ciaran Bowling), enters sporting an arm in a sling and his mom (the dynamic and authentic Sandra Shipley), fusses over him with his dinner and probes what happened with receiving a disability check, we understand their close relationship, and we also understand that mother and son mutually care for each other, living under the same roof, watching out for each other, while other family have gone on to make their own lives.

The hard conditions of the mines remind us of the corporate structure which Lawrence reveals has changed little over one hundred years later. The owners receive all the benefits, and the workers are given low wages and are subcontracted out to keep them hungry and off-balance, so they are unsure of where they stand in the company’s graces. Joe and his brother, like their father before them, were at the mercy of the owners; and their father died as a result of an accident we find out later in the play. This undercurrent of workers vs. owners is the driving undercurrent and reveals that the misery of need and want is what impacts the families who live and depend on coal mining for their survival.